Abstract

This study aimed to examine the relationship between hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), one of the indicators of diabetes, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), one of the indicators of inflammation. Raw data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES, 2015–2017) was analyzed. Among the patients diagnosed with diabetes, 1,479 adults were selected as subjects for our study, and their HbA1c levels, hs-CRP levels, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, level of triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, hypertension, receipt of diagnosis, monthly average income, education, and drinking and smoking habits were recorded. Multiple regression analysis of hs-CRP was performed by dividing hs-CRP into quartiles using HbA1c as the dependent variable. In Model 1, sex, age, and BMI were adjusted, and in Model 2, sex, age, BMI, waist circumference, level of triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol, hypertension, and receipt of diagnosis were adjusted. In Model 3, Model 2 parameters along with monthly average household income, education level, and drinking and smoking habits were adjusted. HbA1c levels increased as the hs-CRP quartile increased, that is, 2nd Quartile=0.307, p=0.003; 3rd Quartile=0.431, p=0.001; and 4th Quartile=0.550, p=0.001. Of the various factors related to diabetes, this study examined the relationship between inflammation and diabetes.

Keywords: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Glycated Hemoglobin A, C-Reactive Protein

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of diabetes is on the rise worldwide. The International Diabetes Federation has predicted that a global diabetes pandemic will occur by 2035, and 1 in every 10 people will be diabetic. In Korea, as of 2016, one out of eight male adults (12.9%) and one out of ten female adults (9.6%) were estimated to have diabetes, which was reported to be close to 10% of all adults in Korea.1,2

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) can be measured in blood samples from patients regardless of their fasting or non-fasting state. Thus, it can be used as an indicator for diabetes rather than measuring blood sugar levels before meals or 2 hours after meals. The American Diabetes Association has added HbA1c≥6.5% as a diagnostic criterion for diabetes.3,4

C-reactive protein (CRP) is a 21,500 Da representative acute phase inflammation response protein, and its levels increase in infection and inflammatory conditions. It is mainly synthesized in the liver by stimulation of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6, and its half-life is up to 19 hours.5 With the advancement of technology, a high sensitivity (hs)-CRP measurement method was developed, enabling the measurement of CRP with high precision even at low concentrations and the measurement of mild CRP elevation due to chronic inflammation.6 In few cases, CRP is known to be produced locally by lymphocytes or smooth muscle cells and monocytes in atherosclerotic lesions.7

According to previous studies, hs-CRP levels are related to race, body mass index (BMI), education level, income, insurance status, disability status, smoking habits, high blood pressure, and diabetes.8 Recently, many studies demonstrated that inflammation plays an important role in the occurrence of arteriosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases, leading to increased interest in this field. In addition, some previous studies suggest that the blood concentration of hs-CRP may help in predicting the development of metabolic syndrome and diabetes in adults by dividing hs-CRP levels into quartiles.

For example, according to the Hoorn Study, the group with high CRP levels had higher fasting blood glucose levels and type 2 diabetes than other groups.9

According to a study examining the relationship between hs-CRP and alcohol consumption, hs-CRP levels were the lowest in people who drank moderately, around 5 to 7 drinks per week.10 There was a J-shaped relation between alcohol intake and hs-CRP levels in women, but no significant relationship was observed in men. Thus, differences based on sex were reported.11 Additionally, it has been reported that since hs-CRP is also related to metabolic syndrome, the concentration of hs-CRP in the blood of people with metabolic syndrome was significantly higher than that of people without metabolic syndrome.12

In the KNHANES, hs-CRP was measured recently. Few studies have been conducted to determine the relationship between diabetes and hs-CRP based on the KNHANES data and none of the studies utilized the data from the 2017 survey. In previous studies, to create a normal distribution for maintaining the characteristics of continuous variables, the log values of hs-CRP were measured and expressed in many cases. Several studies on non-diabetic people have also been performed. Diabetes mellitus is correlated with several factors; indicators associated with diabetes are also associated with bone metabolism indicators, and related factors are increasingly getting more diverse and subdivided.13 Of the various factors related to diabetes, this study examined the relationship between inflammation and diabetes.

In this study, we evaluated the factors that may affect the relationship between hs-CRP and HbA1c in diabetic patients and report the effects of hs-CRP HbA1c levels in diabetic patients while adjusting for the effects of these factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Subjects

Raw data from the KNHANES (2015–2017) was used. Among the subjects diagnosed with diabetes, 1,479 adults were selected for our study. Data on HbA1c levels, hs-CRP levels, sex, age, BMI, waist circumference, levels of triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol, hypertension, receipt of diagnosis, monthly average income, education, and drinking and smoking habits were recorded. Exemption of review was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Gwangju Veterans Hospital (Human 2020-13th-1).

2. Methods

The prevalence of hypertension and screening of diabetic patients were based on a doctor's diagnosis. Among the blood test indicators, hs-CRP was measured by immunoturbidimetry (Cobas, Roche, Germany), and HbA1c was measured by high performance liquid chromatography (Tosoh G8, Tosoh, Japan). HDL-cholesterol was measured by a homogeneous enzymatic colorimetry assay, and triglyceride levels was measured by an enzymatic method. Both constituents were then measured by a biochemical analyzer (Hitachi Automatic Analyzer 7600-210, Hitachi, Japan). Other measurements were based on responses to the questionnaire. People who had smoked more than 5 packs (100 cigarettes) in their lifetime and who still smoked were selected as smokers, and alcohol consumption for at least one month in the past year was considered drinking. BMI was calculated by dividing body weight by the square of height.

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical processing of data was analyzed using the Stata/MP 14.0 program (StataCorp LLC., Texas, USA). All variables were analyzed based on their frequency to show the basic characteristics of subjects by dividing hs-CRP into quartiles. hs-CRP was analyzed by dividing it into quartiles in multiple regression analyses with HbA1c as the dependent variable. In Model 1, sex, age, and BMI were adjusted, and in Model 2, sex, age, BMI, waist circumference, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, and hypertension were adjusted. In Model 3, all Model 2 parameters along with monthly average household income, education level, drinking, and smoking habits were adjusted. p=0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

1. Basic characteristics of research subjects

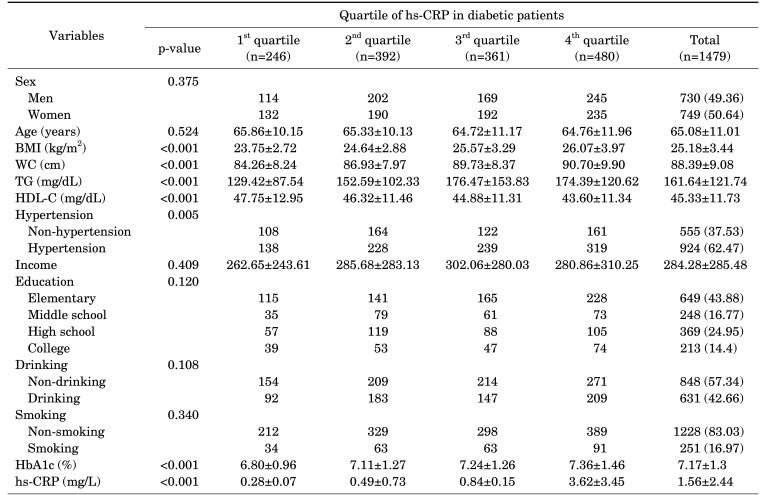

The total number of subjects in the study was 1,479, with an average age of 65.08±11.01 years, average HbA1c level of 7.17±1.3, and average hs-CRP value of 1.56±2.44. Variables such as BMI, waist circumference, triglyceride and HDL-C levels, hypertension, HbA1c, and hs-CRP showed significant differences between the hs-CRP quintile groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Basic characteristics of research subjects by quartile of hs-CRP in diabetic patients.

p-values were calculated by analysis of variance.

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, TG: triglyceride, HDL-C: high density lipoprotein cholesterol, HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c, hs-CRP: high sensitivity C-reactive protein.

2. Multiple regression analysis of hs-CRP using HbA1c as the dependent variable adjusted for variables from Model 1 to 3

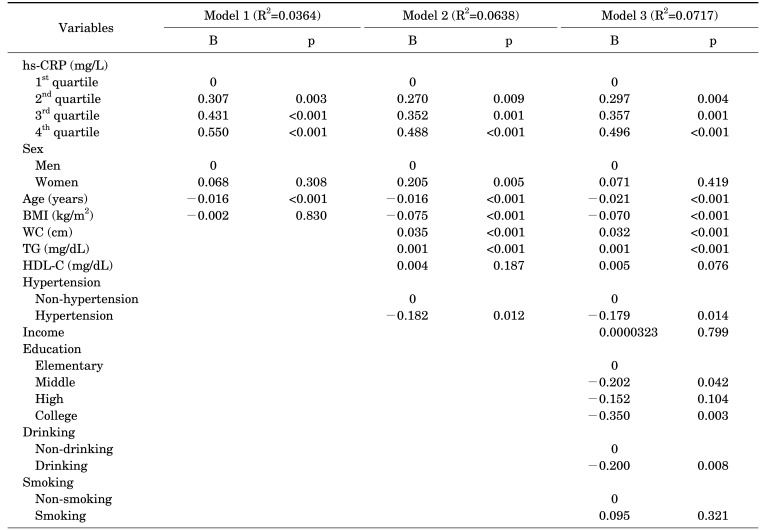

In Model 1, using HbA1c as the dependent variable, which was adjusted for sex, age, and BMI, the regression coefficients for each quartile of hs-CRP were found to be as follows: 2nd quartile (B=0.307, p=0.003), 3rd quartile (B=0.431, p=0.001), and 4th quartile (B=0.550, p=0.001) for sex, age, and BMI, respectively. The regression coefficient of age was −0.016 (p=0.001), and the regression coefficients for sex and BMI were not significant.

In Model 2, the regression coefficient for each quartile of hs-CRP was found to be as follows: 2nd quartile (B=0.270, p=0.009), 3rd quartile (B=0.352, p=0.001), and 4th quartile (B=0.488, p=0.001). In Model 2, with HbA1c as the dependent variable, which was additionally adjusted for waist circumference, levels of triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol, and hypertension, each variable increased to the 4th quartile. In terms of sex, there was a difference of 0.205 (p=0.005) in the regression coefficient of women as compared to men. Age (B=−0.016, p=0.001), BMI (B=−0.075, p=0.001), waist circumference (B=0.035, p=0.001), and triglyceride levels (B=0.001, p=0.001) were significant, but the HDL-cholesterol level (B=0.004, p=0.187) was not significant. The difference in regression coefficients of hypertensive and non-hypertensive subjects was −0.182 (p=0.012).

In Model 3, the regression coefficient for each quartile of hs-CRP was calculated using HbA1c as the dependent variable, which was additionally adjusted for monthly average household income, education level, alcohol consumption, and smoking. The regression coefficient for each quartile of hs-CRP was found to be the 2nd quartile, 1st quartile (B=0.297, p=0.004), 3rd quartile (B=0.357, p=0.001), and 4th quartile (B=0.496, p=0.001) for monthly average household income, education level, alcohol consumption, and smoking, respectively. Similar to Model 2, age (B=−0.021, p=0.001), BMI (B=−0.070, p=0.001), waist circumference (B=0.032, p=0.001), and triglyceride levels (B=0.001, p=0.001) were significant, but HDL-cholesterol (B=0.005, p=0.076) was not significant. The difference in regression coefficients of hypertensive and non-hypertensive subjects was −0.179 (p=0.014). For each education level, the regression coefficients were based on elementary school, middle school (B=−0.202, p=0.042), high school (B=−0.152, p=0.104), and university (B=−0.350, p=0.003). Alcohol consumption was significant at −0.200 (p=0.008), but smoking, income level, and sex were not significant (Table 2).

TABLE 2. Multiple regression analysis of hs-CRP using HbA1c as the dependent variable adjusted for variables of Model 1 to 3.

p-values were calculated by multiple regression analysis.

R2 is adjusted R-squared.

Abbreviations: See Table 1.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to determine the relationship between HbA1c and hs-CRP in diabetic patients. We found that the regression coefficient value increased as the quartile of hs-CRP increased. Thus, the hs-CRP levels affected the HbA1c levels. Even after adjusting for several related variables, HbA1c was found to increase significantly as hs-CRP increased (p=0.001). These results suggest an association between blood sugar levels and inflammation in diabetic patients, similar to previous studies.14 In a study on the relationship between hs-CRP and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients, it was reported that relatively increased hs-CRP in type 2 diabetic patients was associated with increased insulin resistance, even in the normal range.15 Currently, the hypothesis explaining the relationship between markers of inflammatory response and insulin resistance is that chronic inflammation can act as an inducer of insulin resistance or stimulate hs-CRP synthesis by an underlying disease, eventually leading to type 2 diabetes.16,17 For analyzing HbA1c, age, BMI, waist circumference, triglyceride level, hypertension, education level, and alcohol consumption were considered significant variables. Our results support previous studies that suggested the association of CRP with an increased risk of diabetes and metabolic syndrome.14 Sex, HDL-cholesterol level, income, and smoking status were not significant. The explanatory power increased with additional adjustments from Model 1 (R2=0.0364) to Model 2 (R2=0.0638) and Model 3 (R2=0.0717).

Subjects who were diagnosed with hypertension showed a negative relationship with HbA1c. Various drugs (angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, statins, and others) were used as confounders to analyze the effects of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis in the subjects, and fibrate preparations, cilostazol, and aspirin were thought to be administered to these subjects.18 A negative relationship between age and HbA1c suggests differences in adherence to treatment based on age; thus, the younger the patient is, the lower is the patient's adherence to treatment. This is presumed to increase the levels of glycated hemoglobin.19

The reason for selecting factors other than hs-CRP is as follows. In a study suggesting the relationship between metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease incidence in type 2 diabetes, the concentration of hs-CRP was significantly higher in the group with metabolic syndrome than in the group without metabolic syndrome.12 Triglyceride level, hypertension, HDL-cholesterol level, waist circumference, and glycated hemoglobin are factors related to metabolic syndrome. Thus, they were selected to investigate the relationship between diabetes and inflammatory markers and metabolic syndrome.

According to a study by Fröhlich et al.,12 hs-CRP is correlated with BMI, blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, fasting blood sugar, and uric acid among other risk factors for metabolic syndrome. BMI was mostly correlated with hs-CRP and has been reported to be a highly relevant indicator. Thus, BMI was added as a parameter along with sex and age.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the level of glycated hemoglobin was related to the smoking status in type 2 diabetes patients. However, in our study, HbA1c levels did not differ according to smoking habits.20 In addition, fasting blood sugar was shown to have a significant relationship with diabetes in a previous study that identified various indicators according to the income of adult diabetic patients.21 However, in our study, income had little effect on HbA1c.

HbA1c showed a significant relationship with HDL-cholesterol in the non-diabetic group in our study, but a previous study reported an insignificant relationship between HbA1c and HDL-cholesterol in the diabetes patient group. Thus, the relationship between HbA1c and such factors needs to be further analyzed.22

The limitations of this study were as follows. The basic source of data for this study was the KNHANES data, and a complex sample analysis considering weight should be performed. Several previous studies have reported that exercise affects HbA1c levels. However, subjects were not evaluated for exercise and drug use.

This study showed the relationship between inflammation markers, represented by hs-CRP, and glycemic control, represented by HbA1c and based on big data. hs-CRP levels affected HbA1c levels. Even after adjusting for several related variables, HbA1c increased significantly as hs-CRP increased. Thus, the results of the present study can be used as a basis for conducting additional studies to determine the relationship between diabetes and other factors.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT: None declared.

References

- 1.Oh HJ, Choi CW. Relationship of the hs-CRP levels with FBG, fructosamine, and HbA1c in non-diabetic obesity adults. Korean J Clin Lab Sci. 2018;50:190–196. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh KW. Diabetes and osteoporosis. Korean Diabetes J. 2009;33:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee YS, Moon SS. The use of HbA1c for diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in Korea. Korean J Med. 2011;80:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han AL, Shin SR, Park SH, Lee JM. Association of hemoglobin A1c with visceral fat measured by computed tomography in nondiabetic adults. J Agric Med Community Health. 2012;37:215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho YG, Kang JH. C-reactive protein and prevention of cardiovascular disease. Korean J Obes. 2006;15:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JY, Kim MJ, Kim JH. Influence of alcohol consumption on the serum hs-CRP level and prevalence of metabolic syndrome: based on the 2015 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Korean Diet Assoc. 2019;25:83–104. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishikawa T, Imamura T, Hatakeyama K, Date H, Nagoshi T, Kawamoto R, et al. Possible contribution of C-reactive protein within coronary plaque to increasing its own plasma levels across coronary circulation. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:611–614. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee SS, Singh S, Magder LS, Petri M. Predictors of high sensitivity C-reactive protein levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:114–123. doi: 10.1177/0961203307085878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jager A, van Hinsbergh VW, Kostense PJ, Emeis JJ, Nijpels G, Dekker JM, et al. Increased levels of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 are associated with risk of cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetes: the Hoorn study. Diabetes. 2000;49:485–491. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. Alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Circulation. 2003;107:443–447. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000045669.16499.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oliveira A, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, Lopes C. Alcohol intake and systemic markers of inflammation-shape of the association according to sex and body mass index. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:119–125. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fröhlich M, Imhof A, Berg G, Hutchinson WL, Pepys MB, Boeing H, et al. Association between C-reactive protein and features of the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1835–1839. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.12.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seo YH, Shin HY. Correlation between serum osteocalcin and hemoglobin A1c in Gwangju general hospital patients. Korean J Clin Lab Sci. 2018;50:313–319. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Son NE. Influence of ferritin levels and inflammatory markers on HbA1c in the Type 2 Diabetes mellitus patients. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35:1030–1035. doi: 10.12669/pjms.35.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King DE, Mainous AG, 3rd, Buchanan TA, Pearson WS. C-reactive protein and glycemic control in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1535–1539. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Temelkova-Kurktschiev T, Siegert G, Bergmann S, Henkel E, Koehler C, Jaross W, et al. Subclinical inflammation is strongly related to insulin resistance but not to impaired insulin secretion in a high risk population for diabetes. Metabolism. 2002;51:743–749. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.32804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickup JC, Crook MA. Is type II diabetes mellitus a disease of the innate immune system? Diabetologia. 1998;41:1241–1248. doi: 10.1007/s001250051058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selim KM, Sahan D, Muhittin T, Osman C, Mustafa O. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in the aqueous humor of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2010;58:375–379. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.67042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim HJ, Pae SW, Kim DJ, Kim SK, Kim SH, Rhee YM, et al. Association of serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein with risk factors of cardiovascular diseases in type 2 diabetic and nondiabetic subjects without cardiovascular diseases. Korean J Med. 2002;63:36–45. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JE, Park HA, Kang JH, Lee SH, Cho YG, Song HR, et al. State of diabetes care in Korean adults: according to the American Diabetes Association recommendations. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2008;29:658–667. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song MS, Lee MH. Glycated hemoglobins and chronic complications of diabetes mellitus, based on the smoking status of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Korean Acad Soc Home Care Nurs. 2016;23:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho S, Park K. Trends in metabolic risk factors among patients with diabetes mellitus according to income levels: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1998 ~ 2014. J Nutr Health. 2019;52:206–216. [Google Scholar]