Abstract

Introduction The risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) increases during pregnancy and the puerperium such that VTE is a leading cause of maternal mortality.

Methods We describe the clinical characteristics, diagnostic strategies, treatment patterns, and outcomes of women with pregnancy-associated VTE (PA-VTE) enrolled in the Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD (GARFIELD)-VTE. Women of childbearing age (<45 years) were stratified into those with PA-VTE ( n = 183), which included pregnant patients and those within the puerperium, and those with nonpregnancy associated VTE (NPA-VTE; n = 1,187). Patients with PA-VTE were not stratified based upon the stage of pregnancy or puerperium.

Results Women with PA-VTE were younger (30.5 vs. 34.8 years), less likely to have pulmonary embolism (PE) (19.7 vs. 32.3%) and more likely to have left-sided deep vein thrombosis (DVT) (73.9 vs. 54.8%) compared with those with NPA-VTE. The most common risk factors in PA-VTE patients were hospitalization (10.4%), previous surgery (10.4%), and family history of VTE (9.3%). DVT was typically diagnosed by compression ultrasonography (98.7%) and PE by chest computed tomography (75.0%). PA-VTE patients more often received parenteral (43.2 vs. 15.1%) or vitamin K antagonists (VKA) (9.3 vs. 7.6%) therapy alone. NPA-VTE patients more often received a DOAC alone (30.2 vs. 13.7%). The risk (hazard ratio [95% confidence interval]) of all-cause mortality (0.59 [0.18–1.98]), recurrent VTE (0.82 [0.34–1.94]), and major bleeding (1.13 [0.33–3.90]) were comparable between PA-VTE and NPA-VTE patients. Uterine bleeding was the most common complication in both groups.

Conclusion VKAs or DOACs are widely used for treatment of PA-VTE despite limited evidence for their use in this population. Rates of clinical outcomes were comparable between groups.

Keywords: venous thromboembolism, registry, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pregnancy

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. 1 The risk of VTE is increased fivefold to 10-fold in pregnancy and the puerperium, 2 3 complicating 1 in 1,000 deliveries. 4 VTE is one of the leading causes of maternal mortality in the developed world and causes approximately 1.1 deaths per 100,000 deliveries. 5 The increased risk of VTE in pregnancy and the puerperium reflects, at least in part, the hypercoagulability that has evolved to protect women from hemorrhage at the time of childbirth or miscarriage. It is evident even in the first trimester. 6 The risk of VTE is highest immediately after delivery, specifically for 3 to 6 weeks postpartum, after which the risk declines rapidly. 2 7

Despite the increased risk of VTE, the majority of pregnant women do not require routine thromboprophylaxis, with the exception of those with risk factors, such as previous episode of VTE. 6 8 The diagnosis of pregnancy-associated VTE (PA-VTE) is challenging due to the insidious and nonspecific presentation, in addition to the potential for both fetal and maternal complications and the lack of research in this area. 9

Anticoagulation therapy is the mainstay of prevention and treatment in PA-VTE. Most guidelines recommend low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) 9 10 11 12 13 ; vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) are not recommended, as they cross the placental barrier and can be teratogenic in the first trimester and associated with an increased risk of fetal hemorrhage in the third trimester. 14 VKAs are, however, sometimes used in the second trimester of pregnancy and early in the third trimester to prevent valve thrombosis in women with mechanical heart valves and could be used in the same manner for VTE treatment. They are also advocated for use during the postpartum period of PA-VTE. 11 Like VKAs, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) also cross the placenta. They are contraindicated in pregnancy. Conversely however, DOACs are not recommended for use during the postpartum period. 15 Breastfeeding patients were originally excluded from clinical trials evaluating DOAC safety. Recent studies have shown however, that DOACs are excreted in breastmilk during the lactation stage postpartum. 16 17 Although DOAC dose detection in breast milk was low, the safety for breastfeeding infants has not been adequately determined, largely due to lack of trial participation. 18 How widely these principles are applied in the global management of PA-VTE remains uncertain. The purpose of this analysis was to use data from the Global Anticoagulant Registry in the FIELD (GARFIELD)-VTE to compare patient characteristics and trends in diagnosis and therapy among women with PA-VTE versus nonpregnancy associated VTE (NPA-VTE). PA-VTE included patients who were pregnant at the time of diagnosis, or patients who were within the 6 weeks of puerperium.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

The design of GARFIELD-VTE has been described previously. 19 20 Briefly, GARFIELD–VTE (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02155491) is an on-going prospective, observational study that enrolled 10,688 VTE patients from 415 sites in 28 countries. The national coordinating investigators identified care settings that most accurately represented the management of VTE patients in their country. Men and women ≥18 years of age with an objectively confirmed diagnosis of VTE within 30 days of entry into the registry were eligible for inclusion. No specific treatments, tests, or procedures are mandated by the protocol. Decisions to initiate, continue, or change treatment were solely at the discretion of the treating physicians and their patients. For this ancillary study, women greater than 45 years of age were excluded from the analysis.

Data Collection

Data are captured using an electronic case report form (eCRF) designed by eClinicalHealth Services (Stirling, UK) and submitted electronically via a secure website to the registry-coordinating center at the Thrombosis Research Institute, which was responsible for checking the completeness and accuracy of data collected from medical records. The GARFIELD-VTE protocol requires that 10% of all eCRFs are monitored against source documentation, that there is an electronic audit trail for all data modifications, and that critical variables are subjected to additional audit. This study reports data from prospective patients enrolled between the periods May 12, 2014 and January 4, 2017. The data were extracted from the study database on December 8th, 2018.

Definitions

Women with PA-VTE were defined by the investigators as those of 18 to 45 years of age, diagnosed with VTE during any stage of pregnancy or within 6-weeks postpartum. PA-VTE patients were analyzed collectively and thus were not subcategorized based upon trimester or postpartum stage. The control group of women, those with NPA-VTE, were defined as those with 18 to 45 years of age, diagnosed with a VTE who were neither currently pregnant nor in the 6-week puerperium stage post-pregnancy. Clinical outcomes analyzed were all-cause mortality, recurrent VTE episode, bleeding, and arterial events (myocardial infarction/acute coronary syndromes, stroke/transient ischemic accident) over 12-months from VTE diagnosis. Major bleeding was defined according to the International Society of Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria. 21 Nonmajor bleeding was defined as any overt bleeding not meeting the criteria for major bleeding. Outcomes were not centrally adjudicated. Active cancer was defined as cancer that was treated ≤90 days before and up to 30 days after VTE diagnosis. History of cancer was defined as a cancer diagnosis >90 days before the diagnosis of VTE, and not currently being treated.

Ethics Statement

The registry is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines from the International Conference on Harmonization on Good Clinical Practice and Good Pharmaco-epidemiological Practice and adheres to all applicable national laws and regulations. Independent ethics committee for each participating country and the hospital-based institutional review board approved the design of the registry. All patients provided written informed consent to participate. Confidentiality and anonymity of patients recruited into this registry are maintained.

Statistical Analysis

These analyses describe data collected at baseline, i.e., within 30 days before or after VTE diagnosis. Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables are presented as frequency and percentage. Thus, numerical differences are provided only. Patients with missing values were not removed from the study (available case analysis). Percentages are calculated using available data. Hazard ratios were estimated using Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for age, ethnicity, and body mass index (BMI). Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software and SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, United States).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

This analysis includes a cohort of 1,375 women aged ≤45 years, 13% of the full GARFIELD-VTE registry. Patient recruitment according to country and region showed that the majority of patients were recruited from high-income regions such as Europe and Northern America/Australia ( Appendix Table A1 ). Women with VTE were stratified into those with PA-VTE ( n = 183) or NPA-VTE ( n = 1187). Baseline characteristics and clinical care pathways are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and care pathways.

| Variable | NPA-VTE ( N = 1,187) | PA-VTE ( N = 183) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 34.8 (7.0) | 30.5 (5.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Asian | 192 (17.1) | 35 (20.1) |

| Black | 129 (11.5) | 19 (10.9) |

| Caucasian | 683 (60.7) | 95 (54.6) |

| Other | 121 (10.8) | 25 (14.4) |

| Missing | 62 | 9 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 100 (8.7) | 15 (8.4) |

| Current smoker | 185 (16.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Missing | 37 | 5 |

| BMI, kg/m 2 , mean (SD) | 28.2 (8.3) | 27.7 (6.4) |

| Missing | 108 | 12 |

| BMI categories | ||

| < 20 | 107 (9.9) | 12 (7.0) |

| 20–25 | 361 (33.5) | 57 (33.3) |

| 25–30 | 249 (23.1) | 47 (27.5) |

| 30–35 | 175 (16.2) | 37 (21.6) |

| 35–40 | 95 (8.8) | 12 (7.0) |

| ≥40 | 92 (8.5) | 6 (3.5) |

| Missing | 108 | 12 |

| VTE type, n (%) | ||

| DVT | 803 (67.6) | 147 (80.3) |

| PE | 252 (21.2) | 26 (14.2) |

| DVT and PE | 132 (11.1) | 10 (5.5) |

| Site of DVT, n (%) | ||

| Upper limb | 68 (7.2) | 4 (2.5) |

| Lower limb | 847 (90.3) | 151 (96.2) |

| Caval vein | 23 (2.4) | 2 (1.2) |

| Missing | 249 | 26 |

| Unilateral or bilateral DVT, n (%) | ||

| Left | 514 (54.8) | 116 (73.9) |

| Right | 383 (40.8) | 32 (20.4) |

| Both | 41 (4.4) | 9 (5.7) |

| Missing | 249 | 26 |

| Care setting, n (%) | ||

| Hospital | 563 (47.4) | 111 (60.7) |

| Outpatient setting | 31 (2.6) | 3 (1.6) |

| Specialty, n (%) | 519 (43.7) | 61 (33.3) |

| Vascular medicine | 29 (2.4) | 2 (1.1) |

| General practitioner | 45 (3.8) | 6 (3.3) |

| Internal medicine (hematology and intensive care) | 563 (47.4) | 111 (60.7) |

| Emergency medicine | 31 (2.6) | 3 (1.6) |

| Cardiology | 519 (43.7) | 61 (33.3) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PE, pulmonary embolism; SD, standard deviation; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

PA-VTE patients were younger than those with NPA-VTE, with a mean age of 30.5 ± 5.6 years and 34.8 ± 7.0 years, respectively ( Table 1 ). Women with both PA-VTE and NPA-VTE were mainly Caucasian (54.6 and 60.7%). A similar proportion in both groups was obese. Women with PA-VTE were less likely to be current smokers (1.1 vs. 16.1%), and more likely to be treated by internal medicine specialists (60.7 vs. 47.4%) than women with NPA-VTE.

PA-VTE patients were less likely to have PE than patients with NPA-VTE (19.7 and 32.3%), and more likely to have DVT of the lower extremities (96.2 and 90.3%, respectively), almost three quarters of which were left-sided in those with PA-VTE (73.2%). In contrast, there was a more equal distribution in women with NPA-VTE (55.0%).

Risk Factors

Provoking factors must have occurred within the 3 months prior to VTE diagnosis. The most common provoking risk factors in women with PA-VTE were hospitalization (10.4%) and previous surgery (10.4%). Other common predisposing risk factors included a family history of VTE (9.3%) and known thrombophilia (7.7%) ( Table 2 ). In women with NPA-VTE, the most common risk factors were previous surgery (12.0%), previous episode of VTE (10.8%), and oral contraceptive use (34.1%). These women were also more likely to have acute medical illness (6.7 vs. 1.6%), lower limb trauma (8.9 vs. 0.5%), active cancer (4.9 vs. 0.0%), and history of cancer (3.7 vs. 0.5%) than women with PA-VTE.

Table 2. Risk factors at baseline.

| Variable, n (%) | NPA-VTE ( N = 1,187) | PA-VTE ( N = 183) |

|---|---|---|

| Provoking risk factors | ||

| Active cancer | 58 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Acute medical illness | 79 (6.7) | 3 (1.6) |

| Hospitalization | 113 (9.5) | 19 (10.4) |

| Long-haul traveling | 66 (5.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Surgery | 142 (12.0) | 19 (10.4) |

| Trauma of the lower limb | 106 (8.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Predisposing risk factors | ||

| Hormone replacement therapy | 31 (2.6) | 4 (2.2) |

| Oral contraception | 405 (34.1) | 4 (2.2) |

| Recent bleed or anemia | 634 (5.3) | 9 (4.9) |

| Chronic heart failure | 11 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| Chronic immobilization | 51 (4.3) | 4 (2.2) |

| Family history of VTE | 95 (8.0) | 17 (9.3) |

| History of cancer | 45 (3.8) | 1 (0.5) |

| Known thrombophilia | 57 (4.8) | 14 (7.7) |

| Prior episode of DVT and/or PE | 128 (10.8) | 12 (6.6) |

| Renal insufficiency | 9 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Note: Provoking risk factors occurred during 3 months preceding VTE diagnosis.

Diagnostic Strategies

DVT was diagnosed by compression ultrasonography in most women with both PA-VTE (98.7%) and NPA-VTE (95.1%). Other imaging tests included computed tomography (1.3 vs. 5.9%) or contrast venography (1.9 vs. 1.7%), respectively. There was infrequent use of pretest clinical probability scoring schemes in both groups (5.2 vs. 1.3%). Measurement of D-dimer levels was reported in a similar proportion of DVT patients with PA-VTE and NPA-VTE (26.8 vs. 25.1%) ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Diagnostic strategies for deep vein thrombosis.

| Variable, n (%) | NPA-DVT ( N = 935) | PA-DVT ( N = 157) |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmatory diagnostic | ||

| Compression ultrasonography | 889 (95.1) | 155 (98.7) |

| Vein computed tomography | 55 (5.9) | 2 (1.3) |

| Contrast venography | 16 (1.7) | 3 (1.9) |

| Impedance plethysmography | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Magnetic resonance angiography | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other investigation | ||

| D-dimer assay | 235 (25.1) | 42 (26.8) |

| Pretest probability scores (e.g., Wells and Hamilton) | 49 (5.2) | 2 (1.3) |

Abbreviations: NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism.

Note: Numbers represent the number of tests, not patients. Patients may have received more than one test so values are not mutually exclusive.

The diagnosis of PE was often established with spiral chest CT scan/CT pulmonary angiography in women with both PA-VTE and NPA-VTE (86.1 vs. 92.2%, respectively). Other investigations in women with PE included echocardiography (11.1 vs. 14.1%) and measurement of troponin or B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) (16.7 vs. 13.8%), respectively ( Table 4 ). Ventilation perfusion scans were used more frequently in women with PA-VTE compared with those with NPA-VTE (22.2 vs. 14.1%).

Table 4. Diagnostic strategies for pulmonary embolism.

| Variable, n (%) | NPA-PE ( N = 384) | PA-PE ( N = 36) |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmatory diagnostic | ||

| Any CT | 454 (92.2) | 31 (86.1) |

| Ventilation perfusion scan | 54 (14.1) | 8 (22.2) |

| Magnetic resonance angiography | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other investigation | ||

| Biomarkers (troponin and/or BNP) | 53 (13.8) | 6 (16.7) |

| Echocardiography (transthoracic and/or transesophageal) | 54 (14.1) | 4 (11.1) |

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; CTPA, computed tomography pulmonary angiography; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism.

Note: Echocardiography includes transthoracic and/or transesophageal. Any CT includes CTPA, chest CTPA, and spiral CT. Biomarkers include troponin and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). Numbers represent the number of tests, not patients. Patients may have received more than one test so values are not mutually exclusive.

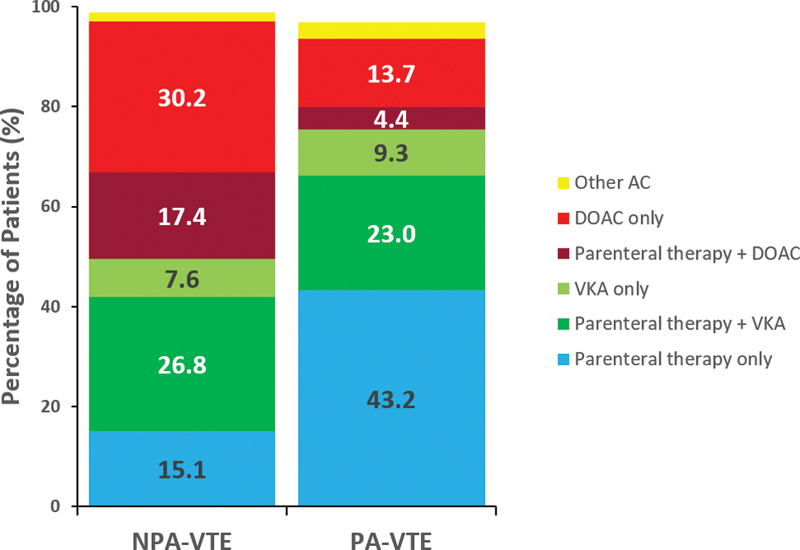

Treatment at Baseline

After VTE diagnosis, most women with PA-VTE (96.7%) and NPA-VTE (98.8%) received anticoagulant therapy ( Fig. 1 ). Women with PA-VTE were more likely to be treated with a parenteral anticoagulant (43.2 vs. 15.1%) or a VKA alone (9.3 vs. 7.6%). Women with NPA-VTE were more likely to be treated with a parenteral anticoagulant in combination with a VKA (26.8 vs. 23.0%) or a DOAC (17.4 vs. 4.4%), or a DOAC alone (30.2 vs. 13.7%) ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Anticoagulant treatment at baseline (up to 30 days after VTE diagnosis). Percentages are calculated from all patients receiving AC treatment, including those who received AC in combination with other modalities of treatment. AC, anticoagulant; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

Thrombolytic or fibrinolytic therapy was rarely used both in women with PA-VTE or NPA-VTE (6.0 and 4.2%), as were surgical or mechanical interventions (2.2 and 1.1%, respectively). The distribution of thrombolytic/fibrinolytic therapy among patients with DVT, PE, or both was comparable between the two groups ( Appendix Table A2 ).

Clinical Outcomes

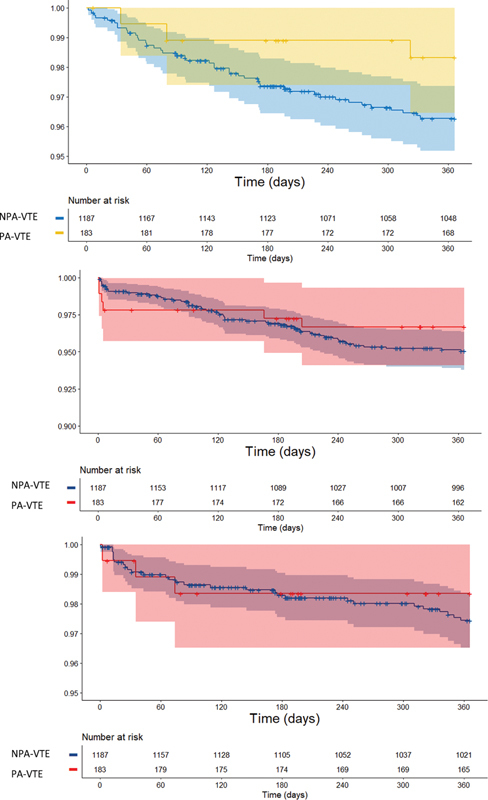

During the 12-months of follow-up, the rates (95% confidence interval) of all-cause mortality were slightly lower in women with PA-VTE than NPA-VTE (1.71 [0.55–5.29] vs. 3.86 [2.87–5.21] per 100-person years, respectively) as were the rates of recurrent VTE, major bleeding, and any bleeding (3.51 [1.58–7.82] vs. 5.19 [4.00–6.75] per 100 person-years, respectively), (1.73 [0.56–5.37] vs. 2.65 [1.84–3.81] per 100 person-years, respectively), and (9.78 [5.99–15.96] vs.13.85 [11.74–16.35] per 100 person-years, respectively). Arterial thrombosis was infrequent in both patient groups ( Table 5 ). The unadjusted time-to-event curves are shown in Fig. 2 .

Table 5. Unadjusted event rates (per 100 person-years) 12-mo after VTE diagnosis.

| NPA-VTE ( N = 1,187) | PA-VTE ( N = 183) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events | Event rate (95% CI) | Number of events | Event rate (95% CI) | |

| All-cause mortality | 43 | 1.71 (0.55–5.29) | 3 | 3.86 (2.87–5.21) |

| Recurrent VTE | 56 | 3.51 (1.58–7.82) | 6 | 5.19 (4.00–6.75) |

| Major bleeding | 29 | 1.73 (0.56–5.37) | 3 | 2.65 (1.84–3.81) |

| Any bleeding | 140 | 9.78 (5.99–15.96) | 16 | 13.85 (11.74–16.35) |

| Myocardial Infarction/ACS | 1 | 0.57 (0.08–4.05) | 1 | 0.09 (0.01–0.64) |

| Stroke/TIA | 2 | N/A | 0 | 0.18 (0.05–0.72) |

Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CI, confidence interval; NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; TIA, transient ischemic attack; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Fig. 2.

Unadjusted time-to-event curves for ( A ) all-cause mortality ( B ) recurrent VTE, and ( C ) major bleeding. Data are shown as percentage of patients and 95% confidence intervals. NPA-VTE, nonpregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism.

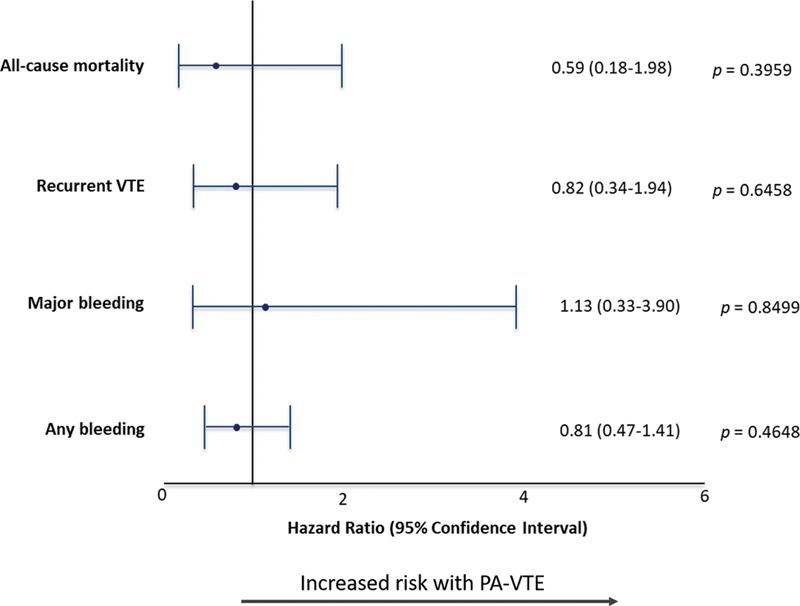

After adjustment for baseline characteristics, the risk of all-cause mortality at 12-months was comparable between women with PA-VTE or NPA-VTE (HR 0.59 [0.18–1.98]) as were the risks of recurrent VTE (HR 0.82 [0.34–1.94]), major bleeding (HR 1.13 [0.33–3.90]), and any bleeding (HR 0.81 [0.47–1.41]) ( Fig. 3 ). Most bleeding events in both groups were uterine (56.3 vs. 55.0%) ( Appendix Table A3 ).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs for 12-month outcomes . Reference group: nonpregnant women. HRs were adjusted for age, ethnicity, and BMI. BMI, body mass index; PA-VTE, pregnancy-associated venous thromboembolism.

Discussion

The outcomes of women with PA-VTE were not significantly different from those with NPA-VTE. Women with PA-VTE were younger, more likely to have left-sided DVT, and less likely to have PE. They were more likely to have had hospitalization, a family history of VTE, or thrombophilia. PA-DVT and PE were mostly diagnosed with compression ultrasonography and chest CT, respectively. Around half of all women with PA-VTE received a VKA or a DOAC. PA-VTE patients comprised a low proportion of the overall GARFIELD-VTE cohort.

Women with PA-VTE, at any stage of pregnancy or within 6 weeks of puerperium, were younger than those with NPA-VTE. Just one-fifth of women with PA-VTE had PE (with or without associated DVT), compared with almost one-third of those with NPA-VTE. This finding is in agreement with a previous study 8 that reported PE in only 21% of pregnant women with VTE. This may be attributed to the fact that PE is less frequently searched for in pregnant women as DVT diagnosis is considered sufficient to treat with anticoagulation. As previously reported, left-sided DVT was more common in PA-VTE, 22 likely reflecting exacerbated compression of the left common iliac vein by the right common iliac artery. 23 24

Previous research has identified risk factors for VTE during pregnancy and postpartum. 6 25 26 27 28 29 The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 12 proposed a checklist for risk factors assessment for VTE, including pre-existing risk factors (previous VTE, thrombophilia, obesity), obstetric risk factors (multiple pregnancy, caesarean section), and transient risk factors (hospitalization, immobility). In this analysis, the most common risk factors in women with PA-VTE were hospitalization, previous surgery, family history of VTE, and previous VTE.

Diagnosis of VTE during pregnancy is challenging, as many of the classical signs and symptoms of VTE may also be associated with normal pregnancy. 30 Current recommendations suggest that pregnant women with suspected DVT should have the diagnosis confirmed with compression ultrasonography, 31 reserving magnetic resonance imaging for suspected iliac vein thrombosis. 32 In GARFIELD-VTE, the diagnosis of PE in PA-VTE was primarily established with CT scanning, encompassing spiral CT scanning, and CT pulmonary angiography. Ventilation–perfusion scanning was less common. The D-dimer assay was used in one-quarter of women with PA-VTE. This is in accordance with guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology, 13 which states that normal levels of D-dimer can exclude PE. However, other guidelines, including the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and American Thoracic Society do not recommend the use of D-dimer in pregnancy 33 34 as the levels of this biomarker increase during pregnancy and return to normal approximately 4 to 6 weeks postpartum. In PA-VTE the use of biomarkers and echocardiography was low as observed in recent evidence. 35

Women with PA-VTE were more likely to be initiated on parenteral therapy, typically LMWH, reflecting guideline recommendations. 11 13 34 36 The safety and efficacy of LMWHs for the treatment of VTE in pregnancy have been shown previously, 37 as they do not cross the placenta and are associated with fewer adverse effects than unfractionated heparin. VKA and DOAC usage, with or without co-prescription of parenteral therapy, was high in PA-VTE patients (50.4%). As VKAs are contraindicated for most pregnant patients it is likely that, within PA-VTE patients, VKAs were administered during the puerperium stage. Patients within the PA-VTE group were less likely to receive DOACs, reflecting that they are both contraindicated for pregnant patients and, due to lack of available safety evidence, are also not recommended during the postpartum stage. In particular, DOACs are not recommended for use during the postpartum breastfeeding stage as DOACs are capable of excreting into breastmilk, 16 17 during the postpartum period due to the increased glomerular filtration rate which induces treatment failure, 38 39 and during the postpartum stage immediately post-delivery when the risk of adverse uterine bleeding is at its highest. The design of the registry avoids the identification of the underlying mechanisms of bleeding complications in both groups. However, the primary mechanisms may be related to benign and malignant structural disease and hormonal or functional alterations of the endometrium. 40

It is important to address potential limitations of this study. First, GARFIELD-VTE did not collect information regarding the date of pregnancy in relation to the VTE episode; only that pregnancy was a risk factor. Thus, we are unable to differentiate between antenatal and postpartum patients, nor subcategorize based upon the stage of pregnancy. Data were not collected regarding antenatal risk factors, such as gestational diabetes and multiple pregnancies, or postnatal risk factors, such as caesarean section and preeclampsia, and uterine bleedings. Finally, the sample size of patients with PA-VTE was small, so we may have had insufficient power to detect differences in outcomes.

In conclusion, findings from the GARFIELD-VTE registry demonstrate contemporary demographic characteristics, risk factors, diagnostic, therapeutic trends, and outcomes in PA-VTE patients. VKAs or DOACs are widely used despite limited evidence and uterine bleeding emerges as a relevant outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank the physicians, nurses, and patients involved in the GARFIELD-VTE registry. Manuscript drafting assistance was provided by Nick Burnley-Hall (Thrombosis Research Institute, London, UK) and Rebecca Watkin (Thrombosis Research Institute, London, UK). SAS programming support was provided by Sujana Katta (Thrombosis Research Institute, London, UK).

Funding Statement

Funding The GARFIELD-VTE Registry is an independent academic research initiative sponsored by the Thrombosis Research Institute (London, UK) and supported by an unrestricted research grant from Bayer Pharma AG (Berlin, Germany).

Conflict of Interest C.J.-S. received consultancy fees from Bayer, Pfizer, Actelion, Boehringer, and Meranini. P.M. received personal fees from Bayer Pharma AG. R.D.L. received research grants and personal fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Bayer AG, and research grants from Amgen Inc, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic PLC, and Sanofi Aventis outside the submitted work. A.G.G.T. received personal fees from Bayer Pharma AG and Janssen. J.I.W. received research support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Heart and Stroke Foundation, and the Canadian Fund for Innovation; honoraria from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ionis, Janssen, Merck, Portola, Pfizer, Servier, Novartis, Anthos, and Tetherex. S.H. received honoraria from Bayer Pharma AG, Bristol Myers Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Pfizer, and Portola. W.A. received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Pharma AG, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Portola, Aspen, Sanofi. S.G. got research funding from Ono, Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi, and Pfizer; personal fees from Thrombosis Research Institute and the American Heart Association. S.Z.G. received research support from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, BMS, BTG EKOS, Daiichi-Sankyo, Janssen, NHLBI, Thrombosis Research Institute; consultancy fees from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim. J.D.N. received honoraria from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Leo Pharma, and Pfizer. S.S. received speaker fees from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol Meyer Squibb, Daiichi-Sankyo, Sanofi Aventis, and Pfizer; consultancy fees from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Sanofi Aventis, Aspen, and Pfizer. H.B. received honoraria from Bayer Pharma (Switzerland) AG. L.G.M. received grants and personal fees from Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Daiichi-Sankyo. P.P. received personal fees from Bayer Pharma AG, Pfizer, Daiichi-Sankyo, and Sanofi. A.K.K. received research grants from Bayer Pharma AG; personal fees from Bayer Pharma AG, Sanofi S.A., Janssen Pharma, Verseon, and Pfizer. D.R. , P.A., A.E.F., and G.K. declare that they have no conflict of interest in the research.

Note

Independent ethics committee and hospital-based institutional review board approvals were obtained, as necessary, for the registry protocol. Patient consent has also been obtained. The lead authors affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported, that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

A full list of investigators is given in the Supplementary Material .

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.van Es N, Coppens M, Schulman S, Middeldorp S, Büller H R. Direct oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists for acute venous thromboembolism: evidence from phase 3 trials. Blood. 2014;124(12):1968–1975. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-571232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heit J A, Kobbervig C E, James A H, Petterson T M, Bailey K R, Melton L J., III Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(10):697–706. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomp E R, Lenselink A M, Rosendaal F R, Doggen C J. Pregnancy, the postpartum period and prothrombotic defects: risk of venous thrombosis in the MEGA study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6(04):632–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jerjes-Sánchez C, García-Sosa A. 2015. Thrombolysis in Special Situations; pp. 211–227. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marik P E, Plante L A. Venous thromboembolic disease and pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(19):2025–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James A H. Venous thromboembolism in pregnancy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(03):326–331. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.184127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamel H, Navi B B, Sriram N, Hovsepian D A, Devereux R B, Elkind M S. Risk of a thrombotic event after the 6-week postpartum period. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1307–1315. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James A H, Jamison M G, Brancazio L R, Myers E R. Venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the postpartum period: incidence, risk factors, and mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(05):1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates S M, Middeldorp S, Rodger M, James A H, Greer I. Guidance for the treatment and prevention of obstetric-associated venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(01):92–128. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics . James A. Practice bulletin no. 123: thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(03):718–729. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates S M, Greer I A, Middeldorp S. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis. 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141 02:e691S–e736S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gynaecologists RCoOa Green-top Guideline No. 37a. Reducing the risk of thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and the puerperiumAccessed July 18, 2019 at:https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg37a/

- 13.The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) . Konstantinides S V, Meyer G, Becattini C. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Respir J. 2019;54(03):2019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bates S M, Greer I A, Hirsh J, Ginsberg J S. Use of antithrombotic agents during pregnancy: the Seventh ACCP Conference on Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy. Chest. 2004;126 03:627S–644S. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3_suppl.627S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen H, Arachchillage D R, Middeldorp S, Beyer-Westendorf J, Abdul-Kadir R. Management of direct oral anticoagulants in women of childbearing potential: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(08):1673–1676. doi: 10.1111/jth.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saito J, Kaneko K, Yakuwa N, Kawasaki H, Yamatani A, Murashima A. Rivaroxaban concentration in breast milk during breastfeeding: a case study. Breastfeed Med. 2019;14(10):748–751. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2019.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiesen M H, Blaich C, Müller C, Streichert T, Pfister R, Michels G. The direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban passes into human breast milk. Chest. 2016;150(01):e1–e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y, Ding A, Arya R, Patel J P. Factors influencing the recruitment of lactating women in a clinical trial involving direct oral anticoagulants: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(06):1511–1518. doi: 10.1007/s11096-018-0734-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weitz J I, Haas S, Ageno W. Global anticoagulant registry in the field - venous thromboembolism (GARFIELD-VTE). Rationale and design. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116(06):1172–1179. doi: 10.1160/TH16-04-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.GARFIELD-VTE investigators . Ageno W, Haas S, Weitz J I. Characteristics and management of patients with venous thromboembolism: the GARFIELD-VTE registry. Thromb Haemost. 2019;119(02):319–327. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis . Schulman S, Kearon C. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(04):692–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray J G, Chan W S. Deep vein thrombosis during pregnancy and the puerperium: a meta-analysis of the period of risk and the leg of presentation. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1999;54(04):265–271. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199904000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cockett F B, Thomas M L. The iliac compression syndrome. Br J Surg. 1965;52(10):816–821. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800521028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavalcante L P, Souza J EDS, Pereira R M. Iliac vein compression syndrome: literature review. J Vasc Bras. 2015;14:78–83. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McColl M D, Ramsay J E, Tait R C. Risk factors for pregnancy associated venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78(04):1183–1188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danilenko-Dixon D R, Heit J A, Silverstein M D. Risk factors for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism during pregnancy or post partum: a population-based, case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(02):104–110. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.107919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simcox L E, Ormesher L, Tower C, Greer I A. Pulmonary thrombo-embolism in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. Breathe (Sheff) 2015;11(04):282–289. doi: 10.1183/20734735.008815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzolai L, Aboyans V, Ageno W. Diagnosis and management of acute deep vein thrombosis: a joint consensus document from the European Society of Cardiology working groups of aorta and peripheral vascular diseases and pulmonary circulation and right ventricular function. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(47):4208–4218. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lockwood C J. Inherited thrombophilias in pregnant patients: detection and treatment paradigm. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(02):333–341. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01760-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wells P S, Anderson D R, Bormanis J.Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management Lancet 1997350(9094):1795–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kearon C, Julian J A, Newman T E, Ginsberg J S. Noninvasive diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis. McMaster diagnostic imaging practice guidelines initiative. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(08):663–677. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-8-199804150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fraser D G, Moody A R, Morgan P S, Martel A L, Davidson I. Diagnosis of lower-limb deep venous thrombosis: a prospective blinded study of magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(02):89–98. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-2-200201150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ATS/STR Committee on Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy . Leung A N, Bull T M, Jaeschke R. An official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline: evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(10):1200–1208. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1575ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gynaecologists RCoOa Green-top Guideline No. 37b. Thromboembolic Disease in Pregnancy and the Puerperium: Acute ManagementAccessed August 16, 2019 at:https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/gtg-37b.pdf

- 35.Rodriguez D, Jerjes-Sanchez C, Fonseca S. Thrombolysis in massive and submassive pulmonary embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium: a systematic review. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(04):929–941. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bates S M, Rajasekhar A, Middeldorp S. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: venous thromboembolism in the context of pregnancy. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3317–3359. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greer I A, Nelson-Piercy C. Low-molecular-weight heparins for thromboprophylaxis and treatment of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy: a systematic review of safety and efficacy. Blood. 2005;106(02):401–407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kearon C, Akl E A, Ornelas J. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(02):315–352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alshawabkeh L, Economy K E, Valente A M. Anticoagulation during pregnancy: evolving strategies with a focus on mechanical valves. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68(16):1804–1813. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maas A H, Euler Mv, Bongers M Y. Practice points in gynecardiology: abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women taking oral anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy. Maturitas. 2015;82(04):355–359. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.