Graphical abstract

Keywords: Dairy, Ultrasound, Properties, Non-thermal, Processing, Emerging technologies

Highlights

-

•

HIU is a potential technology for adoption in the dairy industry.

-

•

Ultrasound significantly modifies the components in milk.

-

•

Ultrasound improves gelation and syneresis during cheese production.

-

•

The texture of dairy products can be manipulated by ultrasound.

-

•

Ultrasound reduces fermentation time or dairy products.

-

•

Improvements depend on time, frequency and intensity of sonication.

Abstract

Alternative methods for improving traditional food processing have increased in the last decades. Additionally, the development of novel dairy products is gaining importance due to an increased consumer demand for palatable, healthy, and minimally processed products. Ultrasonic processing or sonication is a promising alternative technology in the food industry as it has potential to improve the technological and functional properties of milk and dairy products. This review presents a detailed summary of the latest research on the impact of high-intensity ultrasound techniques in dairy processing. It explores the ways in which ultrasound has been employed to enhance milk properties and processes of interest to the dairy industry, such as homogenization, emulsification, yogurt and fermented beverages production, and food safety. Special emphasis has been given to ultrasonic effects on milk components; fermentation and spoilage by microorganisms; and the technological, functional, and sensory properties of dairy foods. Several current and potential applications of ultrasound as a processing technique in milk applications are also discussed in this review.

1. Introduction

Emerging food processing technologies are focussed on the production of palatable, healthy, safe, nutritious and minimally-processed foods. The search for such alternative processes has driven attention to emerging food technologies such as non-thermal technologies, to avoid altering the flavour or nutritional content of foods during production. High-intensity ultrasound (HIU) is a promising emerging technology, especially designed for economy, simplicity, and energy-efficiency. HIU has attracted considerable interest in food science and technology due to its wide range of applications, either in processing or evaluation of products [1], [2]. HIU offers a great potential to control, improve, and accelerate processes without damaging the quality of food and other products. Hence, HIU applications in the food industry including the dairy industry continue to be subject of research.

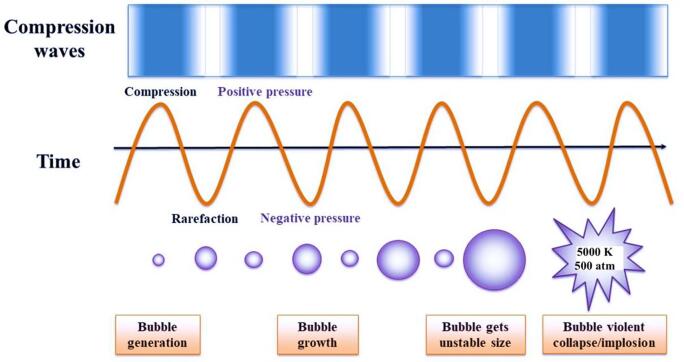

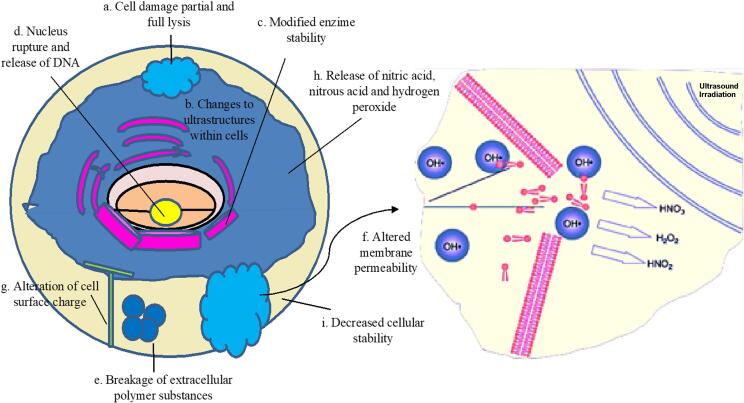

Ultrasound (US) is defined as sound waves of high frequency, above the threshold of human hearing (~20 kHz), ultrasound application can be divided in high intensity - low frequency (I = 10–1000 W/cm2 and F = 20–100 kHz) and low intensity - high frequency (I < 1 W/cm2 and F > 1 MHz) [3]. Ultrasound generates alternating high- and low-pressures, causing compression and expansion (rarefaction) cycles in the medium. Rarefaction leads to the formation of cavitation bubbles, which are tiny vacuum bubbles that occur when the negative pressure exerts. The vacuum bubbles grow over several compression/rarefaction cycles until they cannot absorb more energy and the cavitation bubble undergoes an implosive collapse releasing energy (Fig. 1). This process of bubble generation, growth and implosion is regarded as acoustic cavitation or implosion [4]. Cavitation bubbles generate extreme conditions of temperatures (5000 K) and pressures (500 atm) which can generate very high shear forces [5]. The violent collapse of a cavitation bubble gives rise to physical and chemical effects in the liquid such as microstreaming, agitation, turbulence, microjetting, shock waves, generation of radicals, sonoluminescence etc. [6]. Chemical reactions taking place within these environments are the formation of highly reactive radical species [7], [8], [9], [10]. When an argon-saturated water is sonicated, formation of H and OH radicals takes place as H radicals are reducing in nature, whereas OH radicals are oxidizing in nature. At present, it is known that the radical yield increases with an increase in frequency, it reaches a maximum value and decreases with further increase in the frequency. The highest sonochemical yield is obtained between 200 and 800 kHz [11]. In general, the release energy to the medium, causes structural damage in a nano- micro- or macro-scale [12].

Fig. 1.

Ultrasonic cavitation (Modified from Soria and Villamiel [22]).

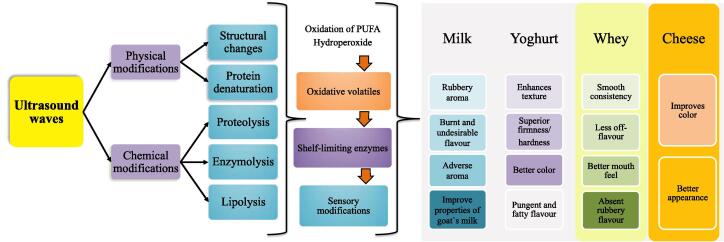

The ultrasound-induced chemical and physical effects provoke changes in milk constituents that lead to significant effects in milk and dairy product properties. These effects are the main topic of this review. Ultrasound has been used in food and dairy processing, in applications such as, the enhancement of whey ultrafiltration, extraction of functional foods, reduction of product viscosity, homogenization of milk fat globules, crystallization of ice and lactose and for cutting of cheeseblocks [13]. In recent years, the research of HIU applied on dairy or dairy by-products has been aimed at reducing processing time or enhance the physicochemical quality of different foods. A large number of studies have been published since 2018. Most of them with very consistent results on the benefits of HIU for the quality parameters of fresh milk, cheese, butter, ice cream, fermented milk products, whey protein preparations, and other beverages.

However, application of ultrasound on the processing of foods have evidenced negative impact of heat on thermo-labile compounds such as, vitamins, and pigments [14]. But the application of ultrasound in beverages has also showed healthy benefits such as increase of levels of antioxidants and bioactive compounds [15]. The effect of HIU application in dairy systems has taken an important place in food science and technology. Its effects on microorganisms have been extensively investigated as a method for preservation [16], [17] due to its role improving safety and delaying food spoilage [18]. As well as in the inactivation of milk enzymes [19]. One of the most relevant uses of ultrasound is in fermentation processes [20] and in the production of functional fermented beverages, with considerable improvement in sensory properties [21]. The purpose of this review is to provide an overview of the latest research on the application of HIU in the processing and preservation of milk and dairy products and to highlight the technological improvements that could be obtained through its application. Particular attention is given to the effects on physicochemical, functional and sensory properties of dairy systems.

2. Physicochemical properties

The ultrasonication processing conditions in foods are highly dissimilar among studies. Variations on intensity, time, pulsations and probes are still wide and heterogeneous. However, promising results in physicochemical properties are found in all these studies for potential application in the dairy industry. Those benefits are discussed in this section and the summary of the results are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recent research (2018-to date) about ultrasound effect in physicochemical properties of milk and dairy products.

| Sample | Experimental parameters | Effect of ultrasound | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milk and milk-based beverages | |||

| Raw sheep milk | Ultrasonic probe.VC Vibra Cell Ultrasound, model VC 130 (Sonics Inc., USA), 20 kHz. Maximum power = 78 W (for 6 or 8 min) or 104 W (for 4 or 6 min). Pulse duration of 4 s. | HIU did not affected proximate composition, free amino acids, or amino acid profile. | [18] |

| Anhydrous milk fat and milk fat/rapeseed oil blends | A 110 mL flow cell system (sonolab SL10 ultrasonic, Syrris Ltd, UK). 20 kHz, 40 W at 28 °C. Recycling mode with a flow rate of 200 mL/min1 and a total volume of 500 mL samples collected at 0, 2.5, 5, 7, and 10 min of ultrasonication. | HIU had no effect on melting behaviour, but it reduced the fat crystal size. No effect on hardness evaluated by needle penetration. | [26] |

| Pasteurized full fat milk. | An 800 mL milk flow cell system (200 mL/min) was used for the study (Sonolab SL10 ultrasonic, Syrris Ltd, United Kingdom) 20 kHz, 10, 30 and 50 W at 27, 50, 30 min and 70 °C. Energy in the flow = 91, 273 and 454 W/L, respectively. | HIU accelerates the acid gel formation at 30 W and 50 °C. Protein denaturation is promoted by HIU increase of temperature. Sonication power higher than 30 W and higher temperature than 50 °C, reduced fat globule size from 3.39 to 3.89 μm to 0.37–1.9 μm. The specific surface area is increased by HIU (from 2.07 to 45.09 m2ag−1fat). | [25] |

| Raw bovine milk | DRC-8-DPP-FGS, Advanced Sonic Processing Systems, USA). Continuous ultrasonication (16 and 20 kHz, nominal 1200 W. 100 W/cm3 and delivered 1.36 kW/pass 14 to 18 min. | Droplets diameters are highly reduced as more passes and shorter exposure to ultrasonication. An increase of submicron droplets was observed at inlet temperature of 54 °C. US reduces gelling times and increases curd firmness at 42 °C. | [28] |

| Pasteurized fresh bovine milk | Ultrasonicator VCX500, Sonicsâ, Newtown, USA). 20 kHz frequency for 3 min with 100% power (500 W. | Ultrasonication does not modify pH, enzyme activity along 21 d, compared to control. US did show a dispersion of 1 µm particles, which could be by reduction of fat globules size. US have a reduced denaturation of a-lacto-albumin and k-casein. | [30] |

| Bovine milk | Ultrasonic processor (Sonics & Materials, Inc, VCX 1500 HV, USA), 20 kHz. 1500 W, Amplitude of 95% for 10 or 15 min. | HIU for 10 min reduced pH and increased specific gravity. Total solids were increased after 7 d of storage. Physical stability is improved by 15 min of HIU, after 7 d of storage. Increased percentage of settled solids. L* is increased with 10 min of HIU and C* is reduced by HIU, after 14 d of storage. a* and b* are not affected. |

[29] |

| Chocolate milk beverage | An ultrasonic device was used. Disruptor, 800 W, (Indaiatuba, Brazil), 19 kHz. Nominal power of 400 W. Energy density 0.3, 0.9, 1.8, 2.4, and 3.0 kJ/cm3. with 13 mm diameter probe. Maximum temperature of 42 °C. | Higher energy densities of HIU lead to higher homogenization of the beverage and smaller particle size distribution of fat globule. HIU affected the antioxidant activity, ACE inhibitory activity, fatty acid profile, and volatile profile. Ultrasonication also reduced the losses of nutrient compounds, and allows a better preservation of short chain fatty acids and medium chain fatty acids. | [27] |

| Cheeses and creams | |||

| Fresh raw milk | Ultrasonic processor Hielscher UP400s , 24 kHz, 400 W, amplitude of 100 and 50% for 0, 5, and 10 min. | HIU increased cheese yield (%), despite an increase of exudate. Yellow tones and coloration in cheese is promoted by HIU at 10 min. But not L*, a*, nor C* colour coordinates are affected. pH increased from 6.6 to 6.74 after 5 min of ultrasonication but reduced at 10 min. | [41] |

| Fresh cream | Ultrasound processor (APU400; Adeeco Co., Iran), 20 kHz, 100 and 300 W for 0, 5, 10 and 15 min. A pulse mode of on-time 2 s and off-time 4 s was used. A 12 mm in diameter ultrasonication probe was immersed to a depth 2 cm Temperature = 50 °C. | Cream particle diameter (0.296–5.867 µm) and particle size distribution were improved with HIU. HIU reduces yellowness. | [43] |

| Retentate of ultrafiltered milk | Ultrasonic Homogenizer (model no. HD2200, Bandelin, Germany), 20, 40, and 60 kHz for 20 min at intensity of 80%. | HIU reduced pH and improved titratable acidity at the end of storage period. However, there was not linear relationship between frequency and acidity. | [42] |

| Fermented milk products | |||

| Fermented milk products | A review of multiple ultrasound parameters. | US reduces processing time and improves quality, stability, and emulsification of products. It may be beneficial when is used as pre-treatment (before inoculation), but it can be detrimental when it is applied during fermentation. Main reported problems are formation of large protein aggregates, and reduction of firmness. | [44] |

| Yogurt and ice cream | A review of multiple ultrasound parameters applied in the production of yoghurt and ice cream | Ultrasound promotes fat drop reduction, increases viscosity, whey coagulation, and water-holding capacity. As well, Ultrasonication reduces ice crystal size and decreases freezing time. | [45] |

| High-protein fermented milk | An ultrasonic device (Sonopuls HD 2200; Bandelin, Germany), 30 W 22.5 W cm−2, energy input of 1765 J/kg1. Booster horn (SH 213 G), and a probe equipped with a titanium flat tip (TT13; d ¼ 13 mm, l ¼ 5 mm). | HIU reduced pH during 9 d of storage. Water-holding capacity was reduced by HIU when pH of 4.8 and 5.0 was reached. A slightly effect on particle size reduction was observed. HIU highly altered yogurt visual appearance. Sonicated yogurt had an increase of homogeneity. | [52] |

| Whey protein concentrates and other whey products | |||

| Chocolate whey beverage | An ultrasound processor with a 13-mm probe was used (Unique, Desruptor 800 W, Indaiatuba, Brazil), 19 kHz, 800 W, 5000 J/ml. Two different processes: A = 20% (160 W for 937 s un 30 mL, with 34 °C of final temperature). B = 90% (720 W for 208 s in 30 mL, with 71 °C of final temperature). | 720 W of HIU for 208 s highly reduced droplet size, contributing to kinetic stability. HIU increased lightness compared to 160 W for 937 s, but it did not modify Chroma. HIU application in any way increased the stability of the whey beverage and reduces hue angle. Zeta values were increased with 160 W for 937 s ultrasonication. | [31] |

| Whey protein concentrate | Ultrasonic processor (Sonics: VCX 750, Vibra Cell Sonics, Sonics & Materials Inc, USA). Maximum net power = 750 W and 220 V. 20 kHz, 20% amplitude for 19.75 min. Temperature = 185 °C inlet and 85 °C outlet. | HIU promotes narrowed size distribution and smaller particle size (0.68 ± 0.23 μm), than controls (2.453 ± 0.717 μm). HIU increased the heat stability from 178 to 1076, heat coagulation time, the solubility of protein from 72.22 to 79.21, and protein aggregation. | [46] |

| Prebiotic inulin-enriched whey beverage. | A 13 mm diameter probe was attached to an ultrasonic device (Unique, Desruptor, 800 W, Brazil), 19 kHz, 0, 200, 400 and 600 W for 3 min. Temperature < 56 °C. | Zeta potential was slightly reduced by the highest power of US (-19 ± 1 mV). US (400 W) promotes cell membrane rupture and increased homogeneity. Particle size distribution is also decreased (5 to 12 µm) by 600 W. Colour of ultrasonicated samples trended to be bluer, duller and with higher Hue values. | [48] |

Physicochemical parameters in dairy products are highly important for quality acceptance. Consumer preference is based on physicochemical quality characteristics, such as colour and texture. Furthermore, processors directly depend on these parameters to guarantee a longer shelf life of the product, proper technological characteristics for further processing, or nutritional benefits for the consumers [23]. Parameters such as pH, fat globule characteristics, oxidative stability or change of the composition are of importance for dairy processors. Hence, to improve those parameters have been always a common aim among researchers and processors. HIU has the potential and already provided positive effects on the physicochemical parameters. Nevertheless, comparisons and combinations with other techniques (i.e. micro-fluidisation or pasteurization), or application on new products, are gaps of knowledge that has been partially researched in the last years.

HIU application in milk and other milk-based beverages, have shown some advantages on quality physicochemical parameters. Lately, buffalo milk [24], sheep milk [18], and supplemented milk [25], [26], [27], in addition to bovine milk [28], [29], [30] have been evaluated after the application of HIU. In general, positive effects of HIU have been confirmed, mainly on size of fat globule or fat crystal size, fat droplets and other milk particles, and altered the curd matrix [24], [26], [30], [31]. The alteration on the size of milk components resulted in physical benefits for the food, for instance; gel strength increase, gel hardness, gel formation acceleration, specific surface area increase, curd firmness reduction, and small particle size distribution of fat [24], [26], [28], [30], [31]. More details on milk components, structural, and functional properties will be given in the next sections.

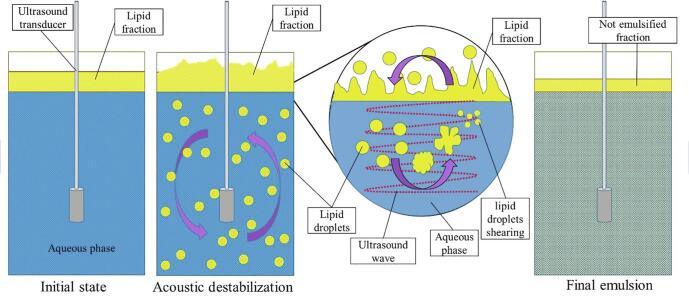

Particle fat size reduction by ultrasonication depends on the ultrasound power applied [32]. For dairy, reduction of droplet size is important in processes such as emulsification. This reduction of size is the first step in the process [33]. First, acoustic vibration lead to a dispersion of fat droplets into the aqueous fraction of the milk through turbulence. Later, cavitation promotes the breakup of fat droplets [34]. Ultrasonication has the capacity to disintegrate the milk fat globule membrane, leading to a reduction of fat globules, smaller than 1 µm, and a modification to a granular surface of the fat globule, due to casein micelles interacting with the disrupted membrane [35]. The mechanism has been proposed in a non-dairy matrix by Kaci et al. [36]. They propose that ultrasonication causes a splitting of big existing droplets to the aqueous phase. There, those droplets are reduced in size by cavitation, a collapse of micro-bubbles resulting from ultrasound waves. The collapse leads to highly localized turbulence that disperses all around the liquid (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Representation of droplet lipid size by high-intensity ultrasound during emulsification (Modified from Kaci et al. [36]).

Further benefits by HIU application in milk and milk compositions, may be classified as technological. HIU have shown to increase the zeta-potential in milk and the stability of the product. Some authors have found that HIU does not promote the nutrient composition change, the free amino acids, or the formation of products from lipid oxidation [18], [24], [26]. On the other hand, HIU has shown a reduced effect on protein denaturation of lacto-albumin [30] and a rising of casein association with fat globules [28], which is beneficial for gelling formation. More information about effects on chemical composition is offered in the Section 3. HIU also reduced pH of milk and increased total solids, without effect on yellowness and redness [27], [29]. From the nutritional point of view, HIU application has the capacity to allow better preservation of fatty acids in milk, compared with common processes such as pasteurization [27].

A factor that may be considered as important to achieve an effect of HIU on physicochemical characteristics of milk and dairy products is the time of HIU application. In Table 1, a trend can be observed when processing time is lower than 10 min. No effects are observed on milk pH or enzyme activity when ultrasonicating for 3 min [30]. In addition, no effect was observed on melting activity or hardness of anhydrous milk fat blends with rapeseed oil after 0 to 10 min [26]. As well, no effect was observed on proximate composition of raw sheep milk when HIU was applied for 6 min [18]. In heavy cream, a non-consistent effect was observed on characteristics such as droplet size and melting peak, and the effect on firmness was not consistent when ultrasonication was from 1 to 90 s [37].

A disadvantage reported from the HIU application in milk, could be that ultrasonication has the capacity to modify colour, an important reduction of lightness and chroma may be detrimental for appearance [29]. More importantly, there is a report of denaturation of major proteins in pasteurized milk, by HIU application [4], [25]. The colour of milk and dairy products depends on a variety of factors. The most relevant factors seem to be the diet, the breed, and the physiological state of the animal. From the diet, carotenoids and retinol deposited by the animal in the milk, seems to be the main factors responsible for milk colour. Other natural dietary components involved in colour of dairy are xanthophills, riboflavins, and tocopherols [38], [39]. Carotenoids and retinol are sensitive to physicochemical factors. After harvesting, milk colour may depend on factors such as fat concentration, photo-degradation, storage conditions, homogenisation or presence of additives. Casein micelles and fat globules are able to disperse light. Hence, milk shows high values of whiteness and lightness. However, any treatment affecting the physical structure of milk may affect its colour [40]. Colour in thermo-sonicated milk changes, having a higher L*, related to a higher homogenization and smaller size of fat globules. Furthermore, cavitation may also promote the release of encapsulated triacylglycerols, cholesterol, and phospholipids in the fat globule, which could change the light dispersion and the milk product [35].

HIU applied in solid or semi-solid dairy products have also shown benefits in the physicochemical parameters of the product, when the technology is applied in raw milk for producing cheese and cream production. An increase in yield was observed in the Mexican Panela cheese production when HIU was applied for 5 or 10 min to the raw material. This could be an interesting result from the economical point of view. However, other parameters such as syneresis or yellowness were increased, while pH was reduced only when 10 min of ultrasonication was applied to the milk. In cheese, similarly to milk and cream, duration seemed to have an interaction with the potency of sonication for affecting characteristics [41]. In feta-type cheese, HIU reduced the pH of the cheese after storage of 60 d. Furthermore, HIU improved the water-holding capacity and gumminess of the product. The authors reported an effect of ripening period and frequency of ultrasonication (variations of 20 to 60 kHz), but no significant interaction between both variables [42]. In cream and butter, the positive effects of HIU are similar. In both foods, HIU increase apparent viscosity, firmness and hardness. More relevant findings are that HIU reduced the churning time and melting peak [37], [43]. Which may also have an important impact on the economics of the production.

HIU application in fermented milk products is well documented. Two reviews have recently been published on the use of the HIU technology on fermented products and in yogurt and ice cream. HIU is an excellent technology for pre-treatment processing, but it does not offer positive effects in the product, when it is applied as post-processing treatment. When it is applied in post-fermentation, it may lead to formation of visible large particles, which affects the texture, reducing firmness [44]. HIU has the potential to increase homogeneity, viscosity, firmness, water-holding capacity, and strength of gel in yogurt. Furthermore, HIU has shown to reduce the crystal size and the freezing time in ice cream [45].

Whey proteins utilization has taken high relevance from different points of view. Whey has also a very high nutritional value. In Table 1, the effect of HIU on some beverage products from whey is provided. Whey proteins have been used in different formulations to produce new dairy products. The use of HIU to improve physicochemical properties on these kind of products is thoroughly documented. Similar to milk, HIU by cavitation effect, reduced droplet size, improved stability and heat stability of the whey beverages, promoted narrowed size distribution and increased homogeneity of the beverages [31], [46], [47], [48]. Ultrasound net power tested for effects on whey proteins in beverages or emulsions varied from 0 to 800 W [31], [46], [47], [48], [49]. Effects on protein internal structure were observed with a power density of 250 W/L (F = 20 or 28 kHz), which will be discussed in the next section [47]. With a net power of 400 W (F = 19 kHz), reductions of Zeta potential have been reported, together with kinetic stability and a decrease in particle size, leading to a higher homogenization in a prebiotic beverage enriched with whey [48]. Higher net power such as 720 and 750 W have resulted in the reduction of particle sizes, an increase of Zeta values, lightness, and kinetic stability [31], as well as an increase of heat stability and protein solubility [46]. High net power such as 500 and 800 W resulted in an increase of in the degree of hydrolysis [49], [50] A possible disadvantage of applying high net powers such as 600 W is that HIU may modify the colour of the product giving the beverages a blue colour with high hue tones compared to control samples [48].

Time of ultrasonication for whey protein beverages or emulsions is again a factor of importance. There is enough evidence that times longer than 15 min may increase the release of sulfhydryl groups, leading to an increase of free thiols in the solutions [26], [50], as well as the formation of protein crosslinking [26], [51].

The most frequently used ultrasound frequencies that have an effect on physicochemical properties of dairy, reported in this section, are around 20 kHz (19–24 kHz). Despite variations in the ultrasonication time or power, the size reduction of fat globules and a higher homogenization are common effects in liquid and semiliquid dairy by applying this range of ultrasonication frequencies. The change in colour parameters of milk and milk-based products is apparently promoted by variations in ultrasonication power. Yellowness and lightness are the coordinates more easily modified with ultrasonication powers greater than 400 W. Higher ultrasonication powers seem to promote changes in chroma or a* coordinates. A reduced number of studies applied a different range of frequencies (40 & 60 kHz) [42]. Nevertheless, no linear relationship between frequency and pH or acidity was found, which implies that ultrasonication may improve those variables, but the changes are not uniform. Furthermore, no improvement of protein or fat content in cheese can be observed by increasing the ultrasonication power [42].

3. Chemical properties

3.1. Whey proteins

The effect of ultrasound on milk proteins has been extensively documented in recent years (Table 2). Ultrasound effectiveness as a pretreatment tool to modify the molecular structure of food proteins is well known [53]. Abadía-García et al. [54] reported that the density of ultrasound in whey protein before hydrolysis with plant proteases exerts a significant effect on proteolysis, reducing hydrolysis time by up to 95% in bromelain hydrolysates. Hence, ultrasound increases the susceptibility to enzymatic hydrolysis, which could be used to produce bioactive peptides from whey proteins. In this regard, Uluko et al. [55] reported an increase in the number of peptides after pretreatment with ultrasound to improve the hydrolysis of the milk protein concentrate. All these effects are due to the changes ultrasound produced in the milk and dairy products’ proteins. On this topic, Wu et al. [50] observed an increase in the inhibitory and immunomodulatory activities of whey protein hydrolysates due to the effects of ultrasound-pretreated whey proteins. They suggested that ultrasound improves enzymolysis in whey proteins for the generation of new bioactive peptides, which can be used as a drug or a functional ingredient. Ahmadi et al. [56]reported that ultrasonication of whey protein concentrate partially replaces heat denaturation prior to transglutaminase treatment. This improves the rheological, functional, and textural properties of whey protein systems. Furthermore, the ultrasonication increased the stability of the foam and reduced the syneresis, obtaining uniform gels with higher hardness. Despite the differences in the characteristics of the equipment and experimental conditions, in all these studies the production of bioactive compounds from samples containing serum proteins was reported, except in the studies by Uluko et al. [55] and Ahmadi et al. [56], who used milk protein concentrate with caseins in its composition.

Table 2.

Effects of ultrasound on the components of dairy products and milk ingredients: proteins, enzymes, fat, and lactose.

| Sample | Experimental parameters | Effect of ultrasound | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whey sweet, protein content on whey 8.13 g/L | Ultrasonic homogenizer (model not specified), 0.092, 0.151, and 0.220 W/mL, 20 kHz, 13 mm probe, 12, 52.5 and 32.25 °C; 5, 10 and 15 min. Papain and bromelain hydrolysis after ultrasound application. | Protein rearrangement and aggregate formation due to changes in denaturation enthalpy, reduction of reactive thiol groups, and changes in secondary structure. | [54] |

| Reconstituted buffalo’s milk and fresh buffalós milk | Ultrasonic horn (3000, Misonix Incorporated, USA); 44, 54 and 66 W, 20 kHz, 3 mm probe, 45 °C; 5, 7.5, 10, 12.5, 15, 17.5 and 20 min. | Reduction of fat globule diameter by up to 92% (sub-micron level) and increase in surface area. Decreased the size of milk particles. Improved the gel strength. Increased free saturated fatty acids and gel hardness. | [24] |

| Whey protein concentrate 10% w/w | Ultrasonic probe (XL2020, Misonix sonicator, USA), 550 W, 20 kHz, 10 mm probe, 25–30 °C; 2.5, 5 and 7.5 min. Transglutaminase hydrolysis after ultrasound application. | Modification of the protein structure to make it more susceptible to transglutaminase. | [56] |

| Buffalo’s milk | Ultrasonic homogenizer (Kirchfeld, Germany), 430 and 338 W, 28 kHz, 0.5 cm tip, 20 °C; 5, 10 and 15 min. | Smaller and more uniform globules of fat as the frequency and duration of the ultrasound increases. | [99] |

| Fresh cream, fat content 30% | Ultrasonic processor (APU400, Adeeco Co., Iran); 100 and 300 W, 20 kHz, 12 mm probe, pulse 2 s on and 4 s off, 50 °C; 5, 10 and 15 min. | Denaturation of protein chains, which were opened to cover the fat globules. Fragmentation of fat globules. | [43] |

| Whey protein concentrate, 10% w/w, pH 6.5–7.1 | Ultrasonic processor (VCX 750, Vibra Cell Sonics, USA), 750 W (amplitude 20%), 20 kHz, 13 mm probe, 49 °C, 20 min. | Decrease in the consistency index in the protein solution, greater elasticity, reduction in the size of aggregates, and greater hydrophobicity surface. | [57] |

| Semi-skimmed sheep milk | Ultrasonic equipment (VC 130, Sonics and Materials Inc., USA), 78 and 104 W, 20 kHz, probe 5 × 60 mm diameter; pulse 4, 6 and 8 s at 40–69 °C. Storage time (30, 90 and 180 days). | There was no release of free fatty acids or changes in the protein profile of fresh and frozen stored semi-skimmed sheep milk due to ultrasound. | [18] |

| Reconstituted whey powder, 6% (in water) | Ultrasonic processor (S-4000, QSonica LLC, USA), 20 kHz. Microbiological preservation of whey (480 W and 600 W, 45 and 55 °C; 6.5, 8 and 10 min) and dairy cultures activation (84 W and 102 W, 37 and 43 °C, 150 s). | There was no denaturation and precipitation of serum proteins compared to pasteurization; smaller diameter particle size. | [20] |

| Full cream UHT milk | Ultrasonic processor (VCX 750, Sonics and Materials, USA), 750 W, 20 kHz, 13 mm probe, 24–26 °C; 2.5, 5, 6, 7.5, and 10 min. | The protein, casein, and lactose contents were unchanged. The fat content increased due to the increase in the surface area of the globules. The lactoperoxidase and alkaline phosphatase enzymes were not inactivated. | [84] |

| Whey protein concentrate, 50 g/kg (w/w) | Ultrasonic horn (Branson Sonifier, USA), 450 W (amplitude 50%), 20 kHz, 19 mm probe, 6 ± 4 °C; 1, 5, 10, 20, 30 and 60 min. | Decrease in denaturation enthalpy with 5 min ultrasound. Prolonged sonication caused protein aggregation. Minor changes in secondary structure and hydrophobicity of proteins. | [58] |

| β-Lactoglobulin (β-LG) and α-Lactalbumin (α-LA), 1.5% w/w, pH 7.0 | Ultrasonic horn (Branson Sonifier, USA), 450 W (amplitude 50%), 20 kHz, < 10 °C; 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min. | Increase of thiol content and superficial hydrophobicity of β-LG. Minor changes in secondary and tertiary structures. α-LA was the most affected. | [59] |

| Fresh pasteurized skim milk, reconstituted micellar casein powder and reconstituted casein powder, 50 and 150 g/kg solutions | Ultrasonic horn (Sonifier 450, Branson, USA), 450 W (amplitude 50%), 20 kHz, 10 °C; 1, 5, 20, 30, and 60 min. | In fresh milk, the fat globule size was reduced but the casein micelle size was unchanged. Soluble whey protein increased and there was no change in soluble calcium content. | [78] |

| Reconstituted micellar casein and tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 50 g/kg solutions | Ultrasonic sonifier (Branson Sonifier 450, USA), 450 W (amplitude 50%, actual power 31 W), 20 kHz, 19 mm horn, 6 ± 4 °C; 1, 5, 10 and 30 min. | Change in the surface hydrophobicity of proteins. Surface charge was inaltered. | [73] |

| Reconstituted calcium-enriched skim milk, 10% w/w solutions, pH 6.7 | Ultrasonic sonifier (Branson Sonifier 450), 450 W (actual power 31 W), 20 kHz, 19 mm horn; 1, 10 and 20 min, <10 °C. | Breakdown of whey/whey and whey/casein aggregates, making them heat stable. Decreased gelation and syneresis times and increased viscosity. | [74] |

| Raw milk, ultrafiltrate retentate, skim milk, skim milk concentrate and cream. | Ultrasonic horn (Branson Sonifier 450, US), 450 W (operated at 101 and 189 W), 20 kHz, 19 mm probe, 50 and < 10 °C; 30 s and 1, 10 and 30 min. | Decreased fat globule size in milk. Formation of flocculated fat particles in cream treated at < 10 °C. | [88] |

| Whey protein emulsion gels, 10% w/w, pH 7.0 | Mono-frequency, simultaneous dual frequency ultrasound (Meibo Biotechnology Co., China), 250 W/L; 20, 28 and 20/28 kHz; for 5, 10, 15 and 20 min. | Ultrasonication reduced alpha-helix, but increased beta-sheets, beta-turn and random coil, increase of random windings exposing tryptophan residues. Multi-frequency highly increased the secondary structure change. | [47] |

| Whey protein isolate, 15% w/w | Ultrasound equipment (no specified) at 300 W/cm2, 24 kHz, <30 °C. 30 min. | Aggregation and gelation due to a greater number of disulfide bonds. | [60] |

| Whole non-homogenized pasteurized milk | Ultrasonic flow cell (Sonolab SL10 ultrasonic, Syrris Ltd, United Kingdom); 91, 273 and 454 W/L; 20 kHz; 27, 50 and 70 °C; 30 min, average residence time in the flow cell 4.13 min. | Increase in gel strength due to denaturation of whey proteins. Changes in the fat globule membrane increased its association with caseins, facilitating the formation of highly functional fat globule/protein complexes. | [25] |

| Fresh cow milk | Ultrasonic processor (S-4000, Misonix, country not specified), 600 W (amplitude 25%, 50%, and 100%), 25 kHz, 19 mm sonotrode; 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 min. | Increase in the size, physical stability, and encapsulation capacity of micellar casein due to the electrostatic repulsion between casein molecules, which increased the availability of interior hydrophobic areas. | [75] |

| Anhydrous milk fat | Ultrasonic flow cell (Sonolab SL10 ultrasonic, Syrris Ltd, United Kingdom), 40 W, 20 kHz, 28 °C; 2.5, 5, 7, and 10 min. | Acceleration of the crystallization process in mixtures with a high content of rapeseed oil. Reduction in crystal size without effects on lipid oxidation. | [26] |

| Prebiotic whey beverages | Ultrasonic device (Unique, Disruptor, Brazil); 200, 400 and 600 W, 19 kHz, 13 mm probe, without controlled temperature (maximum temperature 53 °C), 3 min. | Improvement in the kinetic stability of beverages, avoiding phase separation due to the decrease in particle size, denaturation of whey proteins, and gelling of polysaccharides. | [48] |

| Commercial whey protein concentrate, 5% w/v | Cell disruptor (JY92-IIN, Ningbo Scientz, China), 20 kHz, 800 W, 13 mm probe, <50 °C, 1–10 min. Water bath sonication (70 °C). Hydrolysis with alcalase, papain and trypsin after ultrasound application. | Increase in the degree of hydrolysis of the enzymes. Decreased antigenicity of β-lactoglobulin from 50.81% to 48.82%, contrary to heat treatment. | [49] |

| Retentate of ultrafiltered milk | Ultrasonic homogenizer (HD2200, Sonopuls Bandelin Company, Germany), intensity of 80%; 20, 40 and 60 kHz, probe and temperature not specified, 20 min. | The fat and protein content in cheese was not affected during maturation (60 days). Proteolysis and lipolysis were accelerated. | [42] |

| Whey protein isolates (WPI) and whey protein concentrates, 10% (w/w) | Probe (V1A, Sonics and Materials Inc., USA), 43–48 W/cm2, 20 kHz, 1.2 cm probe, 15 and 30 min. Bath (SO375T, Sonomatic), 1 W/cm2, 40 kHz, 15 and 30 min. | Ultrasonic bath showed a reduction in the size of particles and changes in the composition of the molecular weight of protein fractions. Ultrasonic probe showed a decrease in molecular weight and protein fractionation. | [70] |

| Whey protein isolate (100 g/L) and calcium lactate (final concentration of 1.20 mmol/L), pH 7.0 | Ultrasound processor (JY92-2D, NingBo Scientz Biotechnology Co. Ltd, China); 0, 10.19, 12.74, 15.29 and 17.83 W/cm2 (0, 200, 400, 600 or 800 W), 20 kHz, 0.636 cm probe, 3 s on/1 s off, 25 ± 2 °C, 20 and 40 min. | Improvement in surface hydrophobicity and simple sulfhydryl groups, which led to microstructural changes. HIU (200 to 800 W for 20 and 40 min) reduces the particle size. | [61] |

| Whey protein isolate, pH 7.0, 50 mg/mL, heated at 75 °C for 15 min and cooled at 25 °C | Ultrasound processor (JY92-2D, Ningbo Scientz Biotechnology Co. Ltd, China), 600 W (41–45 W/cm), 20 kHz, pulse 1 s on and 2 s off, 25 °C; 20, 40 and 60 min. | Higher molecular size. Losses of free amino groups. Effects on the β-sheet, β-turn, and random coil of serum proteins. | [51] |

| Recombined milk emulsions | Turbiscan tube (Formulaction, France). One-transductor plate using 400 kHz, 2.45 W/cm2 (Submersible Transducers, Sonosys Ultraschallsysteme GmbH, Germany) and 1.6 MHz, 2.2 W/cm2 (Nebulizer, APC Inter- national Inc., USA), 5 min, 35 °C; and two-transducter plate (400 kHz). | The recombined emulsion and raw milk presented flocculation and coalescence in the cream layer of the emulsion. | [100] |

| Inhomogeneous goat milk | Ultrasonic processor (UP100H, Hielscher, Germany), 100 W (operated at amplitude 60 and 100%), 30 kHz, probe 7 and 10 mm, temperature not specified; 3, 6, and 9 min. | Higher heterogeneity of fat globules (between 0.3 and 4 μm) and increased total area; destruction of the fat globule membrane and formation of casein-fat globule complexes. | [89] |

| Fresh samples of paneer whey | US pretreatment: ultrasonic horn (Sonics and Materials, USA), 100 W (80% duty cycle), 20 kHz; 5, 10 and 15 min. Thermosonication pretreatment: 60 °C, 100–250 W; 5, 10, 15 and 25 min. | Lactose recovery up to 94.5% after ultrafiltration and sonocrystallization. | [97] |

| Whey protein concentrate, concentration not specified | Ultrasonic processor (VCX 750, Vibra Cell Sonics, USA), 750 W (amplitude 20%), 20 kHz, temperature not specified, 19.75 min. | Homogeneous distribution and decreased particle size, increased solubility, greater thermal stability, significant alteration in the secondary structure. | [46] |

| Yogurt, pH 5.7 to 5.1 | Electrodynamic vibration exciter-shaker (TV 51110, Tira GmbH, Schalkau, Germany), 25 to 1000 Hz, acceleration amplitudes 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 m/s2; 200 s and 20 min. | Increase in the number of large particles (greater than0.9 mm) from 34 to 242 particles per 100 g of yogurt. Protein aggregation. | [80] |

| Pasteurized heavy whipping cream (40% fat) | Ultrasonic probe (Misonix Inc., USA), 85 W, 20 kHz, 1.27 cm probe; amplitude of 108 µ for 10, 30, 60, and 90 s. | Weakening of the fat globule membrane. Low melting point triacylglycerol crystallization during whipping and melting of high-melting-point triacylglycerols. Solid fat content was reduced when ultrasonication was applied for 90 s. | [37] |

| Whole raw bovine milk | Ultrasonic milk fractionation prototype device with fully-submersible plate transducers (Sonosys Germany), 283–625 W, 22.2–57.9 °C. Batch sonication: 2 MHz (330 W/L); 5, 10 and 20 min. Stage-based fractionation: 1 MHz and 2 MHz (single or dual), maximum power or 50%, 5 min. | Milk fractionation and formation of a vertically increasing fat concentration gradient, with larger fat globules on the surface. | [34] |

| Skim milk | Ultrasonic reactor, 20 kHz, 30 °C, pH 6.7 and 8.0; 20, 400, and 1600 kHz; 101, 8.6, and 11 kW/m2; < 30 °C, pH 6.7–8.0. | At low frequencies and high pH disruption of casein micelles and protein release from the micellar phase to the serum phase. The released protein formed aggregates with surface charge similar to micelles. | [79] |

| Homogenized pasteurized fresh milk | Ultrasonic processor, 24 kHz, 22 mm diameter probe, 5 min, 45 °C. | Microstructural changes in yogurt, obtaining a honeycomb network with a porous nature and smaller particle sizes (<1μm). | [101] |

| Raw milk | Ultrasonic processor, 400 W, 24 kHz, probe 22 mm, amplitude 70% and 100%; 50, 100, 200, and 300 s. | Significant increases in levels of free fatty acids and oxidation. Milk composition skewed by sonication. CO2 reduced pyrolytic processes and formation of oxidation products caused by ultrasound. | [102] |

| Cristallyzed anhydrous milk fat | Sonicator (S-3000, Misonix Inc., USA); 50, 30, 20 and 5 W; 20 kHz, pulse 10 s on and 5 s off, 10 s. | Decreased crystallization induction time and generation of smaller crystals. | [92] |

| Whey protein isolate | Ultrasonic probe, 130 W, 15 min, pulses of 10 s, < 65 °C. | Little effect on the emulsifying properties of whey proteins, unlike high pressures, which increased free SH groups and surface hydrophobicity and charge. | [103] |

| Whole milk powder, 13% w/w + 0.02% sodium azide | Ultrasonic homogenizer (XL200, Misonix, USA), 50 W, 22.5 kHz, 30 min (0–500 J/mL), without or with temperature control (20–80 °C). | Homogenization of fat globules, denaturation of serum proteins, aggregation of fat globules and proteins. | [62] |

| Sodium caseinate, whey protein isolate and milk protein isolate solutions at 0.5–5 wt%. | Ultrasonics processor (Viber Cell 750, Sonics, USA), 34 W/cm2, 20 kHz, 45 °C, 12 mm probe, 2 min. | Reduction in micelle size and hydrodynamic volume of proteins. MPI emulsions showed very small droplet sizes and stability against coalescence. | [104] |

| Reconstituted lactose solutions (lactose monohydrate 12–18% w/v and acetone 80% v/v). | Ultrasonic bath (Aqua Scientif Instruments, India), 120 W, surface area of 225 cm2, 30 °C, 2–8 min. | Lactose crystallization in 80%–92%, achieving recovery after 4 min of sonication. | [98] |

| Fresh pasteurized homogenized skim milk | Ultrasonic processor (VC750, Vibracell Sonics and Materials, US); 150, 262, 375, 562 and 750 W; 20 kHz, <87 °C, 10 min. | Reduction in fat globule size. Changes in viscosity of yogurt due to protein denaturation, decreasing the content and composition of soluble protein and forming insoluble high-molecular-weight co-aggregates. | [76] |

| Fresh pasteurized homogenized skim milk (93% v/v) and flaxseed oil (7% v/v) | Ultrasonic unit (102 CE, Branson Sonifier), 176 W, 20 kHz, 12 mm probe, water temperature at 22.5 °C, 1–8 min. | Finer sonoemulsified oil globules, stabilized by partially denatured serum proteins. | [87] |

| Fresh pasteurized homogenized skim milk | Ultrasonic horn (102 CE, Branson Sonifier), 90 and 180 W (applied powers), 20 kHz, 12 mm probe, 22–37 °C; 15, 30, 45 and 60 min. | Modification in the size of casein micelles, fat globules, and soluble particles depending on the ultrasonic power. Whey proteins were denatured and formed soluble serum-serum/serum-casein aggregates. | [53] |

| Whey protein isolate, 10% w/w, pH 7.0 | Ultrasonic processor (VCX800, Vibra cell Sonics, USA), 107 W/cm2 (40% amplitude), 20 kHz, 13 mm probe, 10 s on 5 s off, samples were preheated before ultrasonication; 5, 10, 20 and 40 min. | Particle size reduction and increase of free surface sulfhydryl groups in preheated whey protein solutions. Disulfide bond formation after gelation due to reduction in free sulfhydryl content. | [63] |

| β-lactoglobulin (BLG), 2 mg/L, pH 6.5 | Sonifier (150, Branson Ultrasonic Corp., USA), 135 W/cm2 (amplitude 120 μm), probe not specified, 20 kHz, with cooling (25–35 °C) and without cooling (25–65 °C); 5, 15, 30, and 60 min. | Modifications in the secondary structure of BLG. Formation of BLG dimers, trimers, and oligomers. More exposed hydrophobic surfaces. | [71] |

| β-lactoglobulin (BLG, 4 mg/mL) in the presence of D-arabinose, D-lactose, D-glucose, D-ribose, D-galactose and D-fructose monohydrates (217.5 mM) | Sonicator (Branson Sonifier 150, Branson Ultrasonic Corp., USA), 9.5 W (135 W/cm2), 20 kHz, 10–15 °C, 60 min. | Formation of products of the Maillard reaction (MRP). Ribose induced BLG modification in 76% and three bound anhydroribose units. Minor alterations in secondary and tertiary structures. The MRPs showed high antioxidant capacity. | [66] |

| α -Casein and whey powder, 2.0 mg/mL and 40 mg/mL, respectively | Ultrasonic processor (Sonics Vibracell VC 505, USA), 500 W, 20 kHz, 13 mm probe, 60 °C, 30 min. | No change in band intensity on SDS-PAGE gels, therefore there was no change in protein concentration. No change in IgE binding values (allergy). | [67] |

| Fresh Cheddar cheese whey (pasteurized) | Ultrasound reactor with submersible stainless-steel plate transducers (Sonosys Ultraschallsysteme GmbH, Germany) at 45, 66, 143, 46, 95.5 and 187.5 W; 400 and 1000 kHz at 37 °C. | Better fat separation from whey and greater oxidative stability of lyophilized fat-enriched layers. | [86] |

| Milk protein concentrate, 15.4 g/100 mL | Equipment not specified (JY92-IIN), 800 W, 13 mm probe, <50 °C; 1, 3, 5, and 8 min. Neutrase hydrolysis after ultrasound application. | Improvement in degree of hydrolysis during enzymatic hydrolysis. Production of new low-molecular-weight peptides. | [55] |

| Raw milk standardized to 3% fat | Continuous system, 16/20 kHz, 1.36 kW/paso; 0.15, 0.3, and 0.45 L/min; 14–18 min, 42 or 54 °C. | Sub-micron lipid droplets embedded in protein chains of the curd matrix. | [28] |

| Fresh skim milk and cream | Batch sonicator (Branson Ultrasonics 2000 series, USA); 77, 104 and 115 W, 20 kHz, 115 W, 1 and 3 min (two 30 s intervals with a 1 s-break), 72 °C. | Decreased total plasmin activity dependent on storage time in skim milk. Decrease in fat globule size. | [85] |

| Crystallized anhydrous milk fat with and without the use of US | Sonicator (S-3000, Misonix Inc., USA), 0.3175 cm tip, 10 and 15 min, stirring at 200 rpm. | Decrease in the induction time of crystallization and in the generation of more crystals and more viscous materials. | [93] |

| Milk inoculated with starter culture for yogurt production | Ultrasonic generator (CP502, Cole-Parmer Instrument Company, USA); 450, 225 and 90 W; 1, 6 and 10 min; 450, 90, and 225 W; 13 mm probe; 1, 6, and 10 min. US before inoculation: 450, 90, and 225 W; 6 min. US during inoculation: 450, 90, and 225 W, 8 min. | Homogenizing effect, producing fat globules of an average diameter equal to 2 µm or less. | [95] |

| Whey protein | Ultrasonic processor (JY92-II, Haishukesheng Ultrasonic Equipment Co., Ningbo, China); 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 W; 20 kHz, 1.5 cm probe, 2 s on 2 s off, <25 °C, 15 min. Alcalase hydrolysis after ultrasound application. | Increased degree of hydrolysis in whey protein. Whey protein display, resulting in a 43.7% increase in free sulfhydryl content and a 62.6% increase in surface hydrophobicity. Decrease in the α-helix content and significant increase in β-sheets. | [50] |

| Reconstituted milk protein concentrate, ultrafiltered milk with 15% solid content | Ultrasonic horn (CTXNW-10B, Hongxiang Biotechnology Co., China), 600 W (50% amplitude), 20 kHz, 50 mm probe, 5 s on 3 s off, < 50 °C; 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 min. | Particle size reduction. Increase in solubility and emulsifying activity index. Increase in surface hydrophobicity without changes in the molecular weight of proteins. | [64] |

| α-lactalbumin (α-LA), 100 mg/mL, pH 6.0 | Ultrasonic processor (DY-1200Y, Deyangyibang Instruments Co. Ltd, China), 400 W (12.74 W/cm2), 20 kHz, 2 cm diameter probe, pulse 2 s on and 5 s off, 14–20 °C; 20, 40, 60, 80, or 100 min. α-LA was catalyzed by laccase in the presence of ferulic acid. | Improvement of laccase-catalyzed cross-linking of α-LA. Increase in the surface hydrophobility and strength of the gel without significant changes in the conformational structure of the α-LA conjugates catalyzed by laccase. | [105] |

| Micellar casein concentrate | Cell disruptor, 58 W/L, 20 kHz, pulse on 3 s and off 2 s; 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 min. | Increased surface hydrophobicity and reduced particle size. Changes in secondary structure, with an increase in β-sheets and random coils and a reduction in α-helix and β-turns. | [77] |

| Skimmed fresh goat’s milk | Cell disruptor (JY92-IIN, Ningbo Scientz, China), 800 W, 20 kHz, 13 mm probe for 0–20 min. | Smaller particle sizes. Increased denaturation of serum proteins and soluble Ca and P content. | [106] |

| Reconstituted whey protein-concentrate and isolate | Ultrasonic horn (Branson Sonifier, US), 450 W, 20 kHz, 19 mm probe, 6 ± 4 °C; 1, 5, 10, 20 and 60 min. | Reduction in size of suspended insoluble aggregates, compact network of densely packed whey protein aggregates. | [65] |

Arzeni et al. [57] found that ultrasound treatment modifies the functional properties of serum proteins, such as gelation, viscosity, and solubility. This is due to molecular modifications (increase in hydrophobicity and variation in particle size), which are dependent on the nature of the protein and the degree of denaturation and aggregation. On the contrary, Chandrapala et al. observed that ultrasound treatment in serum protein concentrate caused minor changes in the protein structure, preserving the functional properties [58]. Later, the same researchers also reported that the effect of ultrasonication on serum proteins differs substantially when mixtures and/or pure serum proteins are used. Under the same ultrasound conditions, α-lactalbumin is more affected than β-lactoglobulin, with significant increases in surface hydrophobicity. Meanwhile, in the mixture of the two proteins, it decreases surface hydrophobicity because the thiol exposed in β-lactoglobulin interacts with the disulfide bond of α-lactalbumin [59]. Another study with serum protein mixtures reported changes in the physical properties of gels containing large amounts of α-lactalbumin. This suggests that the combined effect of ultrasound- and heat-mediated protein deployment, followed by aggregation and gelation due to a greater number of disulfide bonds, led to the formation of a stronger network with greater water-holding capacity [60]. The effects of ultrasound treatment on the properties of whey proteins are dependent on the experimental conditions (see Table 2). This accounts for the changes in the functional properties of whey proteins observed by Arzeni et al. [57], with temperatures <49 °C during sonication at 750 W (amplitude 20%), while Chandrapala et al. [58], [59] kept the samples at <10 °C during processing at 450 W (50% amplitude).

Jiang et al. [61] reported that ultrasound treatment had a considerable impact on the physical, functional, and oxidative properties of serum proteins in the presence of calcium lactate. They found that ultrasound extensively modified the microstructure and increased the strength of the gel, emulsion capacity, and radical scavenging capacity 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrilhidrazil (DPPH). Ultrasound treatment modifies and restructures whey proteins, solving problems associated with their heat stability and solubility and facilitating their use as a functional ingredient in heat-processed products and protein-rich foods [46]. However, the temperature during the whole milk ultrasound process is important. In this regard, Nguyen and Anema [62] showed that controlled (60 °C) and uncontrolled (<90 °C) temperatures caused the denaturation of serum proteins and gels with greater firmness and shorter gelation time compared to untreated milk. When the ultrasonication temperature was kept below 60 °C, gels with very high firmness were produced without denaturation of the serum proteins. Similar results were obtained by Shen et al. [63], who reported that HIU modifies serum proteins and improves their gelation properties. The water-holding capacity, strength, and firmness of the gel were positively correlated with the content of free surface sulfhydryl (-SH) in preheated protein isolate (WPI) solutions. However, the correlation was negative with the size of the preheated WPI particles and the content of -SH free of acid-induced WPI gels.

Changes in protein functionality are closely related to surface hydrophobicity and reduction in particle size. It has been reported that power ultrasound (20 kHz, 600 W, 50% amplitude) can significantly improve the solubility, emulsification, and gelation of reconstituted and ultrasonicated milk protein concentrate [64]. Zisu et al. [65] also reported a reduction in gelation time and syneresis, as well as improvements in gel resistance in ultrasound-treated isolate and reconstituted whey protein concentrate. Shear forces generated a reduction in the size of the suspended insoluble aggregates, leading to reduced turbidity. They treated dairy ingredients (reconstituted whey protein concentrate, whey protein, and milk protein retainer) with ultrasound for at least 1 min and up to 2.4 min in pilot-scale ultrasonic reactors. They observed a decrease in viscosity and an improvement in heat stability in ingredients containing whey proteins due to the reduction in particle size. These properties were maintained after spray-drying.

Casein, β-lactoglobulin, and α-lactalbumin are the main allergens in milk proteins. Stanic-Vucinic et al. [71] found that ultrasound treatment at 20 kHz frequency, 9.5 W (135 W/cm2) for 5, 15, 30, and 60 min and raising the sample temperature from 25 to 65 °C did not decrease the allergenicity of β-lactoglobulin. They monitored allergenicity in individual patients’ sera, basophil activation test, and skin prick testing in 41 cow’s milk allergy patients. Ultrasound treatment induces changes in secondary structure and the formation of dimers, trimers, and oligomers and increases the exposition of hydrophobic surfaces. As well, makes the crosslinking of β-lactoglobulin more efficient by crosslinking with enzymes that require nucleophilic residues for its action to take place. Similarly, Tammineedi et al. [67] reported that HIU at 20 kHz frequency and 500 W power for up to 30 min at 60 °C did not reduce the allergenicity of α-casein or whey proteins, unlike other technologies such as UV-C light, which reduced the allergenicity of milk proteins 25%–27.7% after 15 min of treatment. Li et al. [68] stated that HIU treatment was effective in reducing the allergenicity of shrimp after 0, 2, 8, 10, and 30 min at 30 kHz, and 800 W at 0 °C and 50 °C. The allergenicity of the boiled shrimps treated at 0 °C y 50 °C decreased by nearly 50% and 40%, respectively, with 10 min of ultrasound treatment.

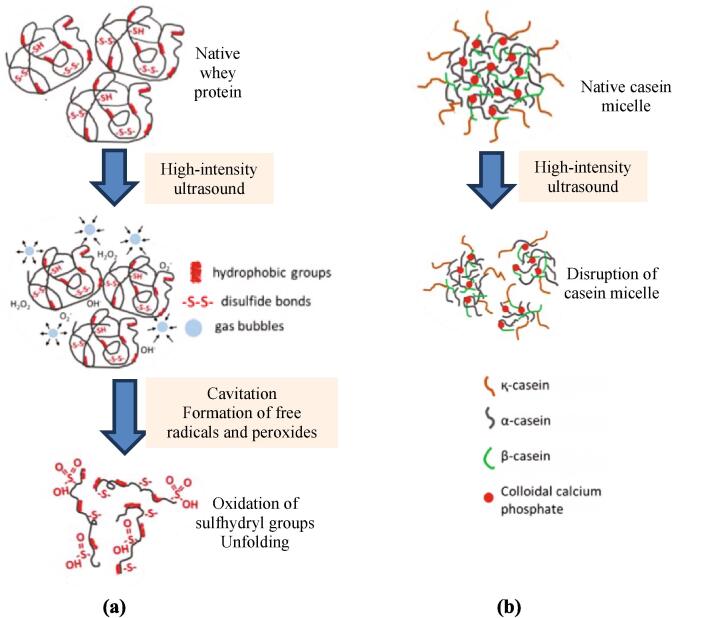

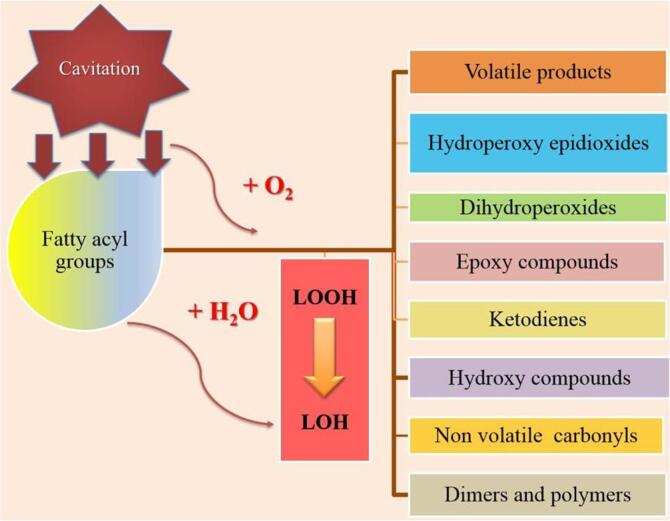

As mentioned in section 1, HIU has cavitation as the mechanism responsible for its effects. Cavitation generates hydrogen peroxide that induces protein oxidation. Free radicals and superoxides promote protein crosslinking and HIU also modifies the hydration status of proteins [13], [69]. Fig. 3 (a) depicts the effect of HIU on the structure of whey protein. Traditional heat treatments induce serum protein aggregation, which is dependent on the formation of disulfide bonds. However, HIU treatment induces structural changes. Jambrak et al. [70] reported that after treatment with an ultrasonic probe of 20 kHz, ultrasound caused a decrease in particle size, narrowed their distribution, and significantly increased the specific free surface, whereas ultrasonic bath treatment with 40 kHz ultrasound for 15 and 30 min showed significant changes in the composition of the molecular weight of whey protein fractions. The ultrasound-induced structural changes in proteins were associated with partial cleavage of intermolecular hydrophobic interactions, rather than peptide or disulphide bonds. Yanjun et al. [64] applied ultrasound (12.5 W and 50% amplitude for 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 min) to reconstituted milk protein concentrate and observed significant changes in physical and functional properties but no significant change in protein molecular weight as evaluated on sodium-dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel. Probably ultrasound duration treatment was not enough to appreciate changes in secondary and primary structure of proteins. Frydenberg et al. [60] studied the mechanisms mediating the effects of HIU (24 kHz, 300 W/cm2) on whey proteins on the molecular level. They observed no change in secondary structure by circular dichroism. However, these authors pointed out that other methods, such as IR spectroscopy, could be applied in order to further investigate the impact of ultrasonication on whey protein secondary structure. They suggest that HIU and heat combined mediates an unfolding of the proteins, making the intramolecular bonds more accessible to the forces of ultrasound. They concluded that the α-La:β-Lg ratio is also important for the inter- and intramolecular interactions formed subsequent to ultrasound-mediated unfolding of the proteins, where higher amounts of α-La appears associated with higher degree of disulfide bonding.

Fig. 3.

Effect of HIU on whey protein structure (a) and casein micelle structure (b) (modified from Nunes and Tavares [72]).

It is important to point out that at low temperatures HIU does not significantly modify the protein secondary and tertiary structures. Stanic-Vucinic et al. [66] investigated whether HIU can promote glycation of β-lactoglobulin by Maillard reaction to safely modify food proteins and their functions. They showed that glycoconjugation of β-lactoglobulin occurs efficiently in the presence of various sugars, especially ribose, and demonstrated improved functional properties of the obtained glycoconjugates with a minor influence on protein secondary and tertiary structures, with a significant increase in the content of early and intermediate Maillard products, fluorescence, darkening intensity and activity and antioxidant solutions. Here, the temperature of the reaction was 10–15 °C whereas in a previous work [71] was 25–35 °C and 25–65 °C. This difference could explain the different effects observed in the secondary structure of proteins.

3.2. Caseins

The effect of ultrasound on caseins is summarized in Table 2. Structural changes have been observed in size, physical stability, and encapsulation capacity of casein due to ultrasound [53], [62], [73], [74], [75], [76], [77]. Chandrapala et al. [78] reported no change in casein micelle size or soluble calcium concentration (mineral balance) of fresh skim milk treated with ultrasound at 450 W, 20 kHz, 10 °C, for 1–60 min). As well, soluble whey protein increased and viscosity decreased due to breakdown of whey-casein protein aggregates in reconstituted casein treated with ultrasound. Liu et al. [79] reported similar results when reconstituted skim milks (10% w/w total solids, pH 6.7–8.0) were ultrasonicated (20, 400 or 1600 kHz at a specific energy input of 286 kJ/kg) at a milk temperature of <30 °C. Application of ultrasound to milk at different pH altered the assembly of the casein micelle in milk, with greater effects at pH 8.0 and frequency of 20 kHz. Sonicated milk at 20 kHz caused greater disruption of casein micelles causing release of protein from the micellar to the serum phase than when sonicated at 400 and 1600 kHz. Regarding protein gels (casein), Chandrapala et al. [73] reported that ultrasonication before the addition of tetrasodium pyrophosphate (TSPP) formed a firm gel with a fine protein network and low syneresis. On the contrary, when ultrasound was applied after the addition of TSPP, it formed a weak and inconsistent gel with high syneresis. The advantages of ultrasound application to the breakdown of protein aggregates have been widely used in the development of calcium-fortified dairy products, including the acid gelation of these products [74]. The use of alkaline pH and ultrasonication in fresh milk have been broadly used to create natural casein micelle nanocapsules with high nanoencapsulation efficiency. This maintains their natural structure and morphological characteristics due to electrostatic repulsions that facilitate interior hydrophobic areas [75]. It can be beneficial in the encapsulation of unsaturated fatty acids, oils, and other hydrophobic compounds used to enrich and fortify food and pharmaceutical products.

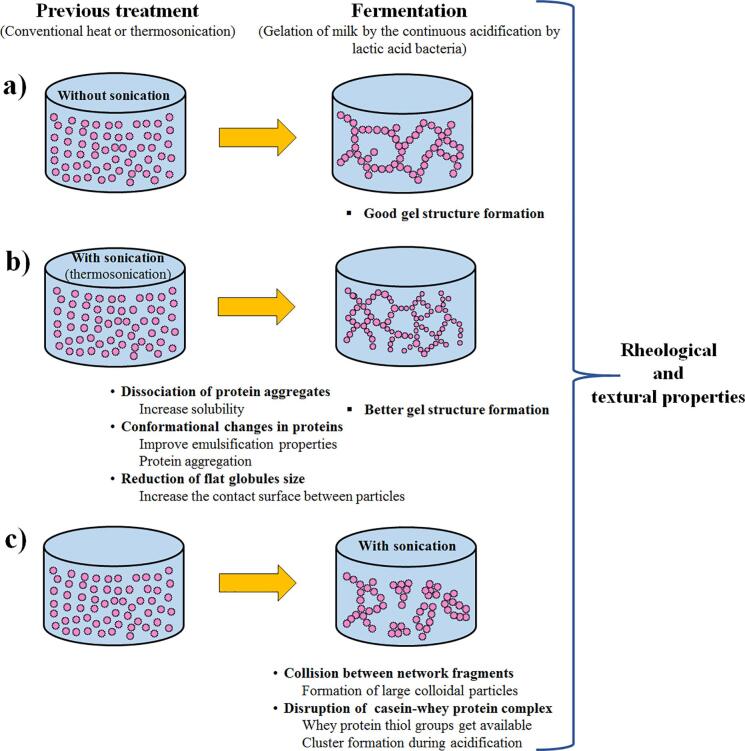

Regarding the benefits of HIU in the manufacture of yogurt, Sfakianakis et al. [76] reported a positive increase in viscosity, a decrease in the pH rate, and a decrease in the duration of pH lag phase of milk during yogurt production fermentation, compared with homogenized milk with conventional pressure. They attributed these positive effects in yogurt made with ultrasonicated milk to the formation of aggregates between whey (denatured whey proteins) and casein molecules. Shanmugam et al. [53]obtained similar results and reported the formation of soluble aggregates of serum-serum/serum-casein in skim milk homogenized, pasteurized, and treated for 30 min with ultrasound, reducing the turbidity of the milk without modifications. In studies with yogurt, Körzendörfer et al. [80] reported the formation of compact yogurts with large particles and low water retention and viscosity due to ultrasonication (30 kHz) of denatured (95 °C, 256 s) skim milk standardized in protein and inoculated with starter cultures (Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus) with a vibration exciter and shaker during the fermentation process. In another study, Körzendörfer and Hinrichs [52] reported the feasibility of applying ultrasound during the thermophilic fermentation of milk. This allowed them to obtain high-protein yogurt with reduced viscosity, which facilitates further processing. In the studies of Sfakianakis et al. [76] and Shanmugam et al. [53], the milk was previously treated with ultrasound before the yogurt fermentation process.

Zhang et al. [77] showed changes in the functional properties and structural characteristics of ultrasound-treated micellar protein concentrate before spray-drying. They observed a significant increase in conductivity, solubility, emulsification, and gelation as the ultrasonication time increased. They explained the changes by citing the exposure of hydrophobic regions from the interior to the surface of the molecules, as well as the reduction in particle size and changes in secondary structures.

Traditional heat treatments such as pasteurization do not alter the structure of the casein micelle due to its lack of tertiary structure, however heat treatments such as ultrapasteurization induce the precipitation of soluble calcium and the solubilization of colloidal calcium phosphate, dissociating κ-casein and some α-caseins from micelles, leading to aggregation and complexation with serum proteins and individual caseins [81], [82], [83]. In contrast, HIU does not produce changes in the native structure but rather with the reduction in particle size [77], [78]. Fig. 3 (b) depicts the effect that HIU has on the structure of the casein micelle.

3.3. Enzymes

In enzyme studies (Table 2), Jiang et al. [51] reported that ultrasonication and preheating applied to increase the crosslinking of transglutaminase catalyzed whey protein isolate and produced polymers with high molecular weights. This in turn produced an increase in emulsifying activity and foaming stability. Therefore, these products have potential as emulsifiers and foam stabilizers for processing and storing food products. In the case of ultrasonicated fresh milk, Balthazar et al. [18] found that, in sheep’s milk, there were no changes in the protein profile or free amino acids, maintaining the quality of the product and its suitability for the production of dairy products. Barukčić et al. [20] obtained interesting results in sweet whey, and reported an increase in stability due to the homogenization caused by the effect of ultrasound. Hence, HIU has the potential to replace conventional pasteurization because whey proteins, being heat-labile, do not precipitate. Cameron et al. [84] also suggested that ultrasonication is an effective means of pasteurization in raw milk; however, it should be combined with an adequate heat treatment to achieve inactivation of alkaline phosphatase and lactoperoxidase. Vijayakumar et al. [85] reported a decrease in total plasmin activity of up to 94% in skim milk and cream treated with HIU and heat (thermosonication). However, the enzymatic activity after 30 d increased up to 5–10 times in skim milk and remained unchanged in cream. This confirms that thermosonication helps to extend the shelf life of milk due to the inactivation of proteases.

3.4. Fat

Structural changes in fat globules of milk by HIU effect modify their integrity, reducing the size and diameter to submicron levels when compared to shear homogenization (Table 2). Abesinghe et al. [24] reported that ultrasonicating buffalo’s milk for 15 min significantly reduces the size of the fat globule compared to traditional homogenization. This led to the formation of better gelling properties for yogurt production while avoiding syneresis. However, lipolytic rancidity was significantly increased due to the increase in the content of free saturated fatty acids in milk. Torkamani et al. [86] reported a decrease in oxidative volatile compounds in skim milk whey powder obtained from pasteurized and ultrasound-treated liquid whey. The volatiles were below the detection threshold and showed oxidative stability during 14 d of storage.

Several authors have described the importance of milk proteins as natural emulsifiers that stabilize emulsions produced with ultrasound assistance [43], [87]. Shanmugam and Ashokkumar [87] reported that whey proteins stabilize sono-emulsified oil globules, which contributes to the production of gels with better textural attributes compared to those produced with non-ultrasound-treated pasteurized skim milk. Amiri et al. [43] reported similar results and observed that ultrasound treatment of whipped cream fragments reduces the size of fat globules. Consequently, denatured proteins open to cover the globules, confining air bubbles and improving the stability and firmness of the whipped cream.

Chandrapala et al. [78] found that the fat globule size was reduced to 10 nm in fresh skim milk treated with ultrasound for 60 min. The formation of flocculated fat particles in ultrasonicated cream at low temperatures (<10 °C) could reduce the energy demand compared to traditional homogenization, carried out at 50 °C [88]. Karlović et al. [89] also reported that milk proteins, especially caseins, adsorb to the membrane surface of fat globules, functioning as natural emulsifiers in ultrasound-treated goat’s milk. In this regard, O’Sullivan et al. [90] showed different emulsifying properties in ultrasound-treated milk proteins. Milk protein isolate produced emulsions with smaller droplet sizes and without coalescence after 28 d. Meanwhile, emulsions produced from whey protein isolate and sodium caseinate had the same droplet sizes as controls without ultrasound (120 nm), despite the reduction in protein size.

HIU application to milk cream modifies the physical properties of butter, depending on the ultrasonication duration. HIU changes the texture and melting behaviour when applied for 10 s. The hardness of the butter is increased due to crystallization of low-melting-point triacylglycerols. It is promoted by forming a narrow lattice. On the other side, the use of long ultrasonication times causes the lattice to melt [37]. Ultrasonication of raw whole cow's milk at 2 MHz, compared to 1 MHz, is more effective for manipulating smaller fat cells retained in the later stages of skimming, eliminating 59% of fat. At 1 MHz, it removes only 47% of the fat after three stages of ultrasound-assisted fractionation [34]. The temperature range of operation utilized in this study is within the ‘optimal’ range between 20 and 55 °C, previously reported by Leong et al. [91]. An aggregation of homogenized fat globules occurs when there is no control on milk temperature treated with ultrasound (>90 °C). Possibly, due to an incorporation of denatured serum proteins. This aggregation is detrimental to the acid gelation of milk [62].

Ultrasound constitutes a technology with potential for application to accelerate the crystallization of mixtures of anhydrous milk fat and vegetable oils, as it is used in dairy ingredients. Martini et al. [92] altered the crystallization behaviour of a lipid model system (anhydrous milk fat) by HIU application. They suggested that HIU may be used as an additional processing variable to improve the lipid crystal lattice and its low-lipid physicochemical characteristics. This would allow for obtaining more viscous materials in lipid-based foods such as mayonnaise, margarine, and spreads, which could be formulated with healthier lipids without affecting the physicochemical and sensory qualities. Wagh et al. [93] also reported that ultrasonication of anhydrous milk fat leads to a decrease in the induction time in crystallization, coupled with the generation of a higher number of crystals and greater viscosity.

In cheese, Torkamani et al. [94] reported different results when evaluating the effects of ultrasound treatment on lipid oxidation in cheddar cheese serum. They found no changes in the composition of phospholipids or in the FFA concentration. However, Jalildazeh et al. [42] reported that ultrasonicated, ultrafiltered milk retentate improves the organoleptic properties of feta-type white cheese, mainly due to lipolysis (content of free fatty acids [FFAs]) and proteolysis (nitrogen soluble in water) that occur during the maturation process (60 d). The differences in the results of these investigations could be due to the characteristics of the treated samples and the experimental and subsequent storage conditions. Torkamani et al. [94] used freshly pasteurized Cheddar cheese whey (fat content not measured), ultrasonicated with a sonotrode and a plate transducer system at 400, 1000 y 2000 kHz for 10 and 30 min at 37 °C. Besides, Jalilzadeh et al. [42] used retentate of ultrafiltered milk (containing 16% fat) using an ultrasonic homogenizer for 20 min at lower frequencies (20, 40 y 60 kHz). Hence, the phenomena of lipolysis and proteolysis occurred naturally during the ripening of the cheese.

In milk inoculated with a thermophilic culture for yogurt, ultrasonication before or after inoculation significantly reduces fat globule size and decreases fermentation time [95]. Regarding the quality of the yogurt, they reported an increase in water-holding capacity and viscosity and a decrease in the syneresis.

3.5. Lactose

Studies that address ultrasound and its effect on carbohydrate metabolism in milk are primarily focused on the hydrolysis of lactose during fermentation processes for the formation of organic acids (mainly lactic, acetic, and propionic acids). This part will be addressed in the “Fermented dairy products” section.

The benefits of ultrasound treatment in the fermentative activity of beneficial strains in milk have reduced the required fermentation times to lower the pH. This facilitates breakdown for the release of extracellular and intracellular enzymes that promote lactose hydrolysis [62], including changes in the number of viable cells [96].

Khaire and Gogate [97] reported a reduction in hydrodynamic size in lactose recovered from ultrasound-treated whey. The pretreatment whey thermosonication improved lactose sonocrystallization in terms of recovery and chemical characteristics so that time of 25 min and power of 250 W resulted in higher recovery (up to 94.5%). In another study by Patel and Murthy [98] on ultrasonicated reconstituted lactose, spontaneous nucleation and seed growth accelerated growth in length and thickness, resulting in rod-shaped seed crystals. Therefore, sonocrystallization using acetone as an antisolvent resulted in a novel process for the rapid recovery of lactose.

Regarding the ultrasound frequency applied, 91% of the consulted papers applied frequencies between 20 and 30 while only 7% of the studies applied frequencies between 0.025 and 1 kHz and 2% used frequencies higher than 1000 kHz. The application of frequencies between 20 and 60 kHz have resulted in modifications in the structure of proteins and formation of aggregates due to denaturation, reduction in particle size [24], [25], [28], [43], [46], [47], [48], [51], [54], [56], [58], [59], [61], [70], [79] and reduction in fat globule size [24], [43], [78], [88], [99]. Additional observations at these frequencies (20 to 60 kHz) were whey protein denaturation and casein-fat globule aggregation [62], [101], [102] as well as proteolysis during cheese maturation [42]. Contrarily other studies did not show any change in dairy protein properties [18], [20] probably due to other experimental parameters such as power, intensity, time or temperature of the ultrasonication treatment. At frequencies between 0.025 and 1 kHz an increase in large yogurt protein aggregates were observed [80] while the use of frequencies between 400 and 2000 promoted milk fractionation and formation of an increasing fat concentration gradient [34] as well as the separation of whey fat which contributes to improve the oxidative stability of cheese [86]. In conclusion, the use of frequencies around 20 kHz present the optimum results regarding the milk chemical components.

4. Rheological and textural properties

The success of any food in a market depends on factors such as its nutritional contribution, safety, shelf life, convenience, and mainly its sensory attributes. The rheological properties are useful for the development of new products, calculation of processes, transportation, and quality control of products [107]. Furthermore, these properties are influenced by the microstructure of the product. The effect of applying ultrasound on the rheological properties in milk and dairy products depends on factors such as the volume of the sample, the heat generated, and the density of the ultrasound [56]. Flow properties identify the type of fluid. Newtonian fluids are characterized by a flow index (n) equal to 1, and most dairy products behave like non-Newtonian fluids with n values less than 1.

These fluids are known as pseudoplastics or shear-thinning fluids since their apparent viscosity decreases with increasing shear rate (γ) [27]. Various mathematical models can describe the different flow patterns of fluids. The most commonly applied models for pseudoplastic fluids are the Power Law model (τ = kγn) and the Herschel-Bulkley model (τ = kγn + τ0), where n is the flow index (dimensionless), k is the consistency index (Pa.sn), and τ is the yield stress (Pa). In these models, k is taken as an analogy of viscosity. The effect of ultrasound treatments on the n and k indices has been evaluated by some authors of studies in milk and dairy products, which are discussed below.

Regarding the viscoelastic properties, these provide valuable information about solid or semi-solid dairy products, such as creams, cheeses, and fermented dairy products [101], [108]. Tests such as the deformation or frequency sweep can provide information about the behaviour of the storage modulus (G') and the loss modulus (G''), which define the elastic and viscous behaviour of the materials, and are also related to the softness and firmness of gel-like structures, as is the case with fermented products. In addition, these types of tests can also provide information about possible long-term flow behaviour, an important indicator for packaging selection and shelf-life determination [109].

Texture is an important attribute to consumers and it can determine the acceptance of a specific product [110]. This attribute depends on the microstructure of the product and is evaluated by consumers through the senses. However, one way to obtain more objective data is through a texture profile analysis (TPA). Here, the sample is subjected to two deformations to simulate chewing [109], [111]. Findings related to parameters such as firmness, adhesiveness, cohesiveness, and elasticity are obtained from the resulting graph [111]. Most research on the effect of ultrasound on the textural properties of dairy products has been done on fermented products. Table 3 summarizes the effects of applying ultrasound on the rheological and textural properties of milk and dairy products, which are discussed below.

Table 3.

Effect of ultrasound on the rheological and textural properties of milk and dairy products.

| Sample | Experimental parameters | Effect of ultrasound | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy emulsions (7–15% olive oil, 14% sucrose, 11% skimmed milk powder). | Ultrasonic processor UP400S with a titanium probe (H22D, l = 22 cm). 24 kHz for 3 min, energy density and amplitude were 85 W/cm2 and 120 µm respectively. | Ultrasonication promoted lower values in apparent viscosity and k with weaker structures. | [107] |

| Yogurt (Raw cow milk with 3.02% fat, 3.01% protein). | Ultrasonic processor UW3200 with an ultrasonic probe (TT13, diameter = 13 mm). 24 kHz, 15 min, 100, 125 or 150 W, 70 °C. Conventional Process: 90 °C, 10 min. In both process, samples of 800 mL were transferred into beakers (1L). | Increases in HIU power promoted decrease in apparent viscosity. | [110] |

| Yogurt (Fat content: 0.1, 1.5 and 3.5%) | Ultrasonic processor (BerHielscher UP 400S) with an ultrasonic probe (Horn H22D, diameter dip = 22 mm). 200 mL milk samples in 250 mL beaker. 24 kHz, 400 W, 10 min, 45–72 °C. Conventional Process: 90 °C, 10 min. | Thermosonication increased the viscosity of the product and the storage modulus G'. | [101] |

| Soft cheese (Raw whole milk). | Ultrasonic processor (Hielscher UP400S) with a 22 mm diameter probe. 24 kHz, 400 W, 15 s; 1, 10, and 30 min; 63 or 72 °C. Sample of 500 mL. Conventional Process; 63 °C, 10 min or 72 °C, 15 s. | Thermosonication increased cheese yield (20.6%) and decreased hardness. The cheeses obtained from thermosonicated milk crumbled easier, which is desirable in this product. | [113] |