Abstract

目的

总结初诊急性早幼粒细胞白血病(APL)早期死亡患者的临床特征,分析早期死亡的危险因素和直接死亡原因,同时对患者进行生存分析。

方法

回顾性分析2011年1月至2017年12月苏州大学附属第一医院、苏州大学附属第一医院广慈分院、苏州弘慈血液病医院收治的368例初诊APL患者的临床特征,分析早期死亡的独立危险因素,比较出血性早期死亡与非出血性早期死亡患者的临床特征,并对所有APL患者进行生存分析。

结果

368例初诊APL患者中早期死亡31例,早期病死率为8.4%,从诊断至死亡的中位时间为7(0~29)d。比较早期死亡患者与非早期死亡患者的临床特征,应用Logistic回归模型进行多因素分析显示,年龄≥50岁和初诊时WBC≥10×109/L为初诊APL患者发生早期死亡的独立危险因素(P值均<0.01)。31例早期死亡患者中有27例(87.1%)的直接死亡原因为出血,出血是<50岁患者的唯一死亡原因,≥50岁患者的主要死亡原因。比较出血性早期死亡患者与非出血性早期死亡患者的临床特征,提示出血性早期死亡患者的中位年龄和间接胆红素水平较非出血性早期死亡患者低(P<0.05)。所有患者中位随访时间为41.0(0.3~101.4)个月。2年总生存(OS)率为(93.5±1.3)%,5年OS率为(91.0±1.5)%。2年无病生存(DFS)率为(98.8±0.6)%,5年DFS率为(97.1±0.9)%。≥50岁与<50岁患者的2年OS率分别为79.3%和94.2%(P=0.000);2年DFS率分别为92.3%和98.1%(P=0.023)。高危患者与非高危患者的2年OS率分别为77.3%和96.7%(P=0.000);2年DFS率分别为94.0%和98.4%(P=0.139)。

结论

年龄≥50岁和WBC≥10×109/L是APL患者早期死亡的独立危险因素;高危和低危APL的早期病死率有差异而DFS率差异无统计学意义。

Keywords: 白血病,早幼粒细胞,急性, 早期死亡, 老年, 高危

Abstract

Objective

To summarize the clinical characteristics of an early death in patients with de novo acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), analyze the risk factors and direct causes of early death, and perform survival analysis.

Methods

The clinical data of 368 patients with de novo APL in three centers (First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University, Soochow Guangci Hospital, and Soochow Hopes Hospital of Hematology) during January 2011–December 2017 were retrospectively analyzed. The clinical characteristics of patients who suffered hemorrhagic early death and non-hemorrhagic early death were compared. The risk factors for early death, survival, and prognosis of patients with APL were analyzed.

Results

Among the 368 de novo APL patients, 31 died early with an early mortality rate of 8.4%. The median time from diagnosis to death was 7 (0–29) d. On comparison of the clinical characteristics of patients with early death and non-early death and subsequent multivariate analysis using a logistic regression model, it was observed that age ≥50 years and WBC ≥10×109/L were independent risk factors for early death (P<0.01). A total of 27 (87.1%) of the 31 early deaths was directly attributed to hemorrhage as the immediate cause of early death. Hemorrhage was the only cause of death in patients <50 years old and the major cause of death in patients ≥50 years old. A comparison of the clinical characteristics of patients with hemorrhagic early death and patients with non-hemorrhagic early death suggested that the median age and indirect bilirubin concentration of patients with hemorrhagic early death were lower than those with non-hemorrhagic early death (P<0.05). The median follow-up time for all patients was 41.0 (0.3–101.4) months. The 2-year overall survival (OS) rate was (93.5±1.3) %, and the 5-year OS rate was (91.0±1.5) %. The 2-year disease-free survival (DFS) rate was (98.8±0.6) %, and the 5-year DFS rate was (97.1±0.9) %. The 2-year OS rate of patients ≥50 years old and patients <50 years old was 79.3% vs 94.2%, P=0.000; the 2-year DFS rate was 92.3% vs 98.1%, P=0.023. The respective 2-year OS rates of high-risk and non-high-risk patients were 77.3% and 96.7% (P=0.000) and the respective 2-year DFS rates were 94.0% and 98.4% (P=0.139).

Conclusion

Age and WBC are independent prognostic factors for early death. We observed a difference in early mortality between high-risk and low-risk APL, but no difference in DFS rate.

Keywords: Leukemia, acute, promyelocytic; Early death; Elderly; High risk

在过去20年中,随着全反式维甲酸(ATRA)、砷剂(ATO)与以蒽环类为基础的化疗药物的联合应用,急性早幼粒细胞白血病(APL)预后显著改善[1]–[5]。但早期死亡仍然是目前APL治疗的主要难题。有学者指出,在ATRA治疗时代,APL患者诱导治疗失败的原因几乎均为早期死亡[6]。本研究旨在分析APL患者早期死亡的高危因素,比较出血性早期死亡患者与非出血性早期死亡患者的临床特征,并对本中心的APL患者进行预后分析。

病例与方法

1.病例资料:收集苏州大学附属第一医院、苏州大学附属第一医院广慈分院、苏州弘慈血液病医院2011至2017年诊治的368例初诊APL患者的临床资料,所有患者诊断均符合中国急性早幼粒细胞白血病诊疗指南(2018年版)[7]。早期死亡患者共31例,其中男19例,女12例。中位年龄49(16~68)岁,≥50岁患者14例,占45.2%。

2.研究方法:收集368例初诊APL患者的发病年龄、活动状态评分(ECOG)、外周血常规、乳酸脱氢酶(LDH)、预后分层、外周血及骨髓早幼粒细胞比例(含原始细胞)及总生存(OS)、无病生存(DFS)情况。对早期死亡患者及存活患者进行组间比较,分析APL早期死亡的危险因素;对早期出血性死亡及早期非出血性死亡患者的临床特征进行比较;最后对所有初诊APL患者进行生存分析。

3.定义:早期死亡指在开始治疗前或诱导治疗后30 d内因任何原因死亡。分子学缓解(mCR)定义为骨髓、外周血、脑脊液及其他部位未检测出PML-RARα融合基因转录样本。分子学复发定义为在间隔2~4周的两次骨髓样本多重PCR定性检测PML-RARα融合基因为阳性,或者多重PCR定量检测为阳性。复发定义为PML-RARα融合基因转为阳性,并经28 d内复查证实,形态学复发,或发生中枢神经系统白血病(CNSL)。

OS时间为从诊断之日起至因任何原因死亡或末次随访的时间。DFS时间为从完全缓解(CR)开始至复发或因任何原因死亡或末次随访的时间。

按以下标准进行预后分层。低危:WBC<10×109/L,PLT≥40×109/L。中危:WBC<10×109/L,PLT<40×109/L。高危:WBC ≥10×109/L。

4.临床观察变量:包括患者性别、年龄、ECOG评分、初诊WBC、HGB、PLT、初诊时外周血及骨髓早幼粒细胞比例(含原始细胞)、LDH、危险度分层等。

5.治疗方案:所有初诊APL患者在疑诊后立即口服ATRA,同时积极输血支持。诱导治疗:确诊为APL后,应用ATRA 25 mg·m−2·d−1联合三氧化二砷0.16 mg·kg−1·d−1双诱导治疗直到CR,诱导治疗过程中根据患者WBC酌情应用羟基脲或蒽环类药物。

巩固治疗中非高危组予去甲氧柔红霉素(IDA)8 mg·m−2·d−1×3 d,3~4个疗程;高危组予IDA 8 mg·m−2·d−1×3 d,阿糖胞苷(Ara-C)1.0 g·m−2·12 h−1×3 d,2个疗程。

非高危组的维持治疗每3个月为1个周期,第1个月:ATRA 25 mg·m−2·d−1×14 d,间歇14 d;第2~3个月:亚砷酸0.16 mg·kg−1·d−1或复方黄黛片60 mg·kg−1·d−1×14 d,间歇14 d。完成8个周期,维持治疗期总计约2年。高危组的维持治疗每3个月为1个周期,ATRA 25 mg·m−2·d−1,第1~14天;6-巯基嘌呤(6-MP)50~90 mg·m−2·d−1,第15~90天;甲氨蝶呤5~15 mg/m2,每周1次,共11次。共8个周期,维持治疗期为2年余。

6.随访:通过查阅住院病历、门诊检查、电话联系等方式进行随访,所有患者随访至2019年4月30日或死亡。

7.统计学处理:所有统计应用SPSS 20.0进行统计学处理。检验水准设定P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。患者数据资料的比较,分类变量采用卡方检验,连续变量资料如果服从正态分布采用t检验,如果不服从正态分布采用秩和检验。单因素分析中P<0.05的变量进入多因素分析,应用Logistic回归模型进行多因素分析,应用逐步向后法选择最终变量。使用Kaplan-Meier法分析OS及DFS,并应用Log-rank检验进行组间比较。

结果

1.患者临床特征:本研究共收集368例初诊APL患者资料,其临床特征详见表1。其中男200例,女168例,男女比例为1.2∶1。中位年龄38(13~70)岁,≥50岁患者73例,占19.8%。低危组患者71例(19.3%),中危组患者200例(54.3%),高危组患者97例(26.4%)。

表1. 368例初诊急性早幼粒细胞白血病患者及非早期死亡、早期死亡组临床特征.

| 临床特征 | 全部患者(368例) | 非早期死亡患者(337例) | 早期死亡患者(31例) | t值 | P值 |

| 性别(例,男/女) | 200/168 | 181/156 | 19/12 | 0.417 | |

| 年龄[岁,M(范围)] | 38(13~70) | 37(13~70) | 49(16~68) | −3.64 | 0.000 |

| ≥50岁患者[例(%)] | 73(19.8) | 59(17.5) | 14(45.2) | 0.000 | |

| WBC[×109/L,M(范围)] | 2.52(0.15~114.80) | 2.33(0.15~114.80) | 16.71(0.20~77.17) | −3.56 | 0.000 |

| HGB[g/L,M(范围)] | 90(16~173) | 90(16~173) | 85(45~124) | 1.58 | 0.114 |

| PLT[×109/L,M(范围)] | 23(2~279) | 24(16~173) | 21(7~64) | 1.75 | 0.119 |

| 危险度分层[例(%)] | 0.000 | ||||

| 低危 | 71(19.3) | 71(21.1) | 0(0.0) | ||

| 中危 | 200(54.3) | 191(56.7) | 9(29.0) | ||

| 高危 | 97(26.4) | 75(22.3) | 22(71.0) | ||

| LDH [U/L,M(范围)]a | 311(102~4004) | 294(102~4004) | 558(162~1596) | −2.76 | 0.000 |

| 外周血早幼粒细胞[%,M(范围)]b | 30(0~98) | 24(0~98) | 77.5(0~90) | −4.21 | 0.000 |

| 骨髓早幼粒细胞[%,M(范围)]c | 85(13~99) | 86(13~99) | 84.5(58~94) | −0.21 | 0.678 |

注:a 84例患者资料缺失;b 143例患者资料缺失;c 39例患者资料缺失

早期死亡患者31例,早期病死率8.4%。≥50岁患者的早期病死率为19.2%(14/73);<50岁患者的早期病死率为5.8%(17/295)。低危、中危和高危患者的早期病死率分别为0(0/71),4.5%(9/200),22.7%(22/97)。

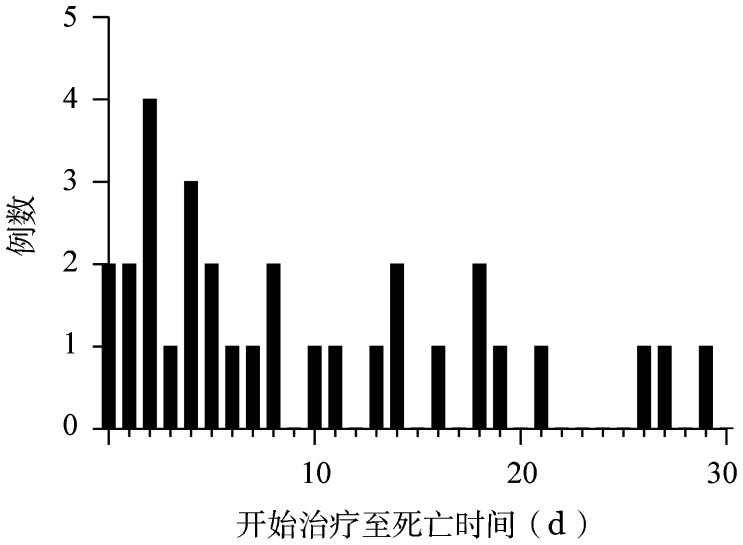

从诊断至死亡的中位时间为7(0~29)d。有2例(6.5%)患者在治疗前死亡,19例(61.3%)早期死亡发生在治疗后10 d内,仅4例(12.9%)发生在治疗开始的20 d以后(图1)。

图1. 初诊急性早幼粒细胞白血病患者早期死亡时间分布.

2.早期死亡的危险因素:早期死亡和非早期死亡患者临床特征的比较见表1。初诊APL早期死亡患者的年龄、WBC、LDH、外周血早幼粒细胞比例均明显高于非早期死亡患者,差异有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)。

对以上变量进行单因素分析,结果显示:年龄≥50岁(P=0.000)、初诊时WBC≥10×109/L(P=0.000)、LDH≥252 U/L(P=0.001)、外周血早幼粒细胞≥50%(P=0.000)是初诊APL发生早期死亡的影响因素(表2)。采用逐步Logistic回归模型进行多因素分析,结果表明,年龄≥50岁(OR=5.165,95% CI 2.203~12.110,P=0.000)、初诊时WBC≥10×109/L(OR=10.248,95%CI 4.323~24.280,P=0.000)为初诊APL患者发生早期死亡的独立危险因素(P<0.001)。

表2. 初诊急性早幼粒细胞白血病早期死亡危险因素单因素分析.

| 因素 | 例数 | 早期死亡[例(%)] | χ2值 | P值 | |

| 年龄 | 13.652 | 0.000 | |||

| ≥50岁 | 73 | 14(19.2) | |||

| <50岁 | 295 | 17(5.8) | |||

| WBC | 34.704 | 0.000 | |||

| ≥10×109/L | 97 | 22(22.7) | |||

| <10×109/L | 271 | 9(3.3) | |||

| LDH | 11.563 | 0.001 | |||

| ≥252 U/L | 193 | 27(14.0) | |||

| <252 U/L | 91 | 1(1.1) | |||

| 外周血早幼粒细胞 | 16.761 | 0.000 | |||

| ≥50% | 83 | 18(21.7) | |||

| <50% | 142 | 6(4.2) | |||

初诊时WBC≥10×109/L的高危患者共97例,初诊时不同范围WBC患者的早期病死率见表3。初诊时WBC≥10×109/L是APL患者早期死亡的独立危险因素,但早期病死率与初诊WBC增高并无正相关性。

表3. 高危急性早幼粒细胞白血病早期死亡与初诊时WBC的关系.

| 初诊时WBC(×109/L) | 例数 | 早期死亡[例(%)] |

| 10~<20 | 40 | 8(20.0) |

| 20~<50 | 30 | 10(33.3) |

| 50~<100 | 25 | 4(16.0) |

| ≥100 | 2 | 0(0) |

3.出血性死亡与非出血性死亡: 分析31例早期死亡患者的直接死亡原因,共有27例(87.1%)患者死于重要脏器出血,其中以脑出血最常见(54.9%),其次为肺出血(32.3%);其余死亡原因包括:分化综合征(6.5%)、感染(3.2%)、中枢神经系统白血病(3.2%)。

年轻患者的死亡原因均为重要脏器出血,而老年患者死亡原因较为复杂,除出血外,还包括分化综合征、感染、CNSL。比较出血性早期死亡患者和非出血性早期死亡患者临床特征,两组患者中位年龄分别为46岁和53岁,前者明显低于后者(P=0.013)。出血性早期死亡组患者的间接胆红素水平相对较低(6.9 µmol/L对12.0 µmol/L,P=0.043)。其余临床特征,如血常规、凝血功能、早幼粒细胞比例等差异均无统计学意义(P值均>0.05)。

4.预后: 截至随访终点,所有患者中位随访时间为41.0(0.3~101.4)个月。2年OS率为(93.5±1.3)%,5年OS率为(91.0±1.5)%。非早期死亡患者的2年DFS率为(98.8±0.6)%,5年DFS率为(97.1±0.9)%。

非早期死亡的337例患者中,失访患者共有26例。复发患者共13例,复发中位时间为23.9(2.5~58.8)个月,复发后死亡4例(30.8%),目前仍存活7例(53.8%),2例(15.4%)患者复发后失访。

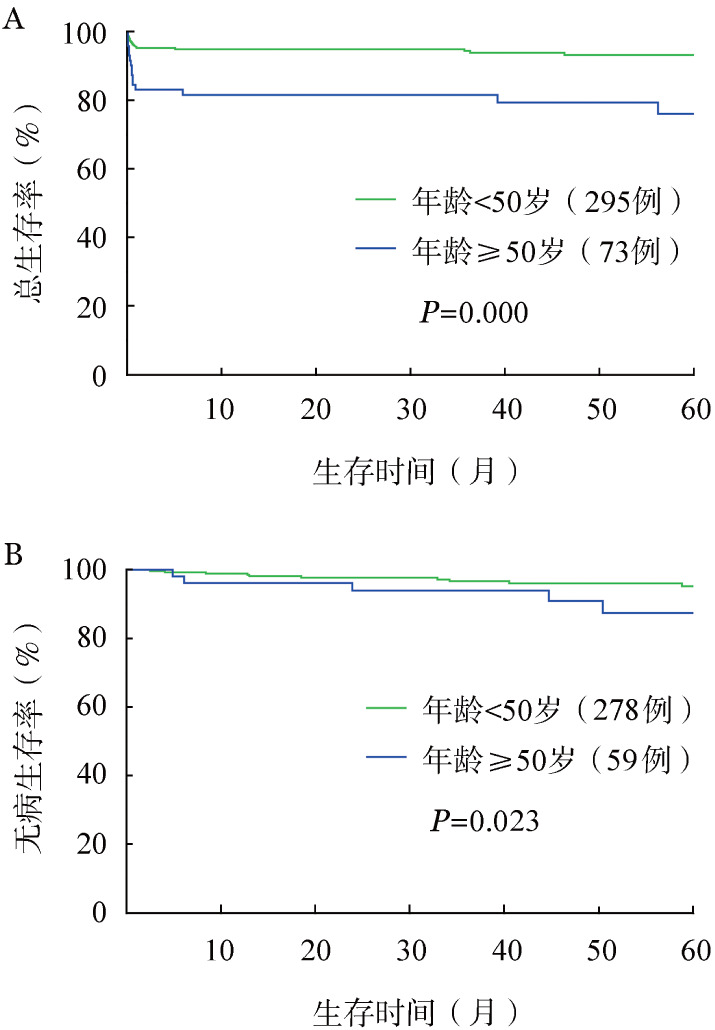

≥50岁和<50岁患者的2年OS率分别为79.3%和94.2%(P=0.000);2年DFS率分别为92.3%和98.1%(P=0.023)(图2)。≥50岁患者预后较差,差异有统计学意义。

图2. ≥50岁和<50岁急性早幼粒细胞白血病患者的总生存(A)和无病生存(B)曲线比较.

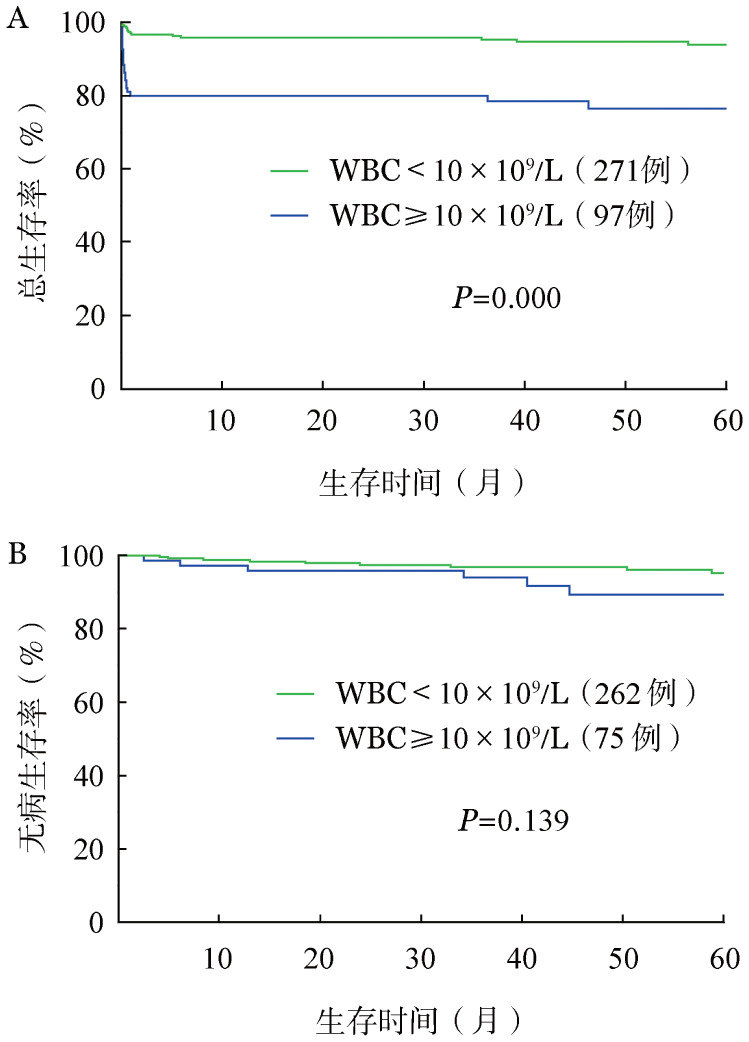

高危患者与非高危患者的2年OS率分别为77.3%和96.7%(P=0.000);2年DFS率分别为94.0%和98.4%(P=0.139)(图3)。高危组患者的2年OS率较低,差异有统计学意义,而两组患者的DFS差异无统计学意义。

图3. 高危与非高危急性早幼粒细胞白血病患者的总生存(A)和无病生存(B)曲线比较.

讨论

APL是一种以凝血功能异常与治愈率高为特征的特殊类型的AML[8]。尽管目前APL预后良好,早期死亡仍然是初诊APL治疗的主要难题。

在APL的临床试验研究报告中,早期病死率为5%~10%[4],[9]–[11]。由于选择偏倚,临床试验往往会排除高龄、体力状态差、脏器功能异常或有其他合并症的患者。在PETHEMA LPA 96和LPA 99临床试验中,被排除入组的患者半数有危及生命的严重出血症状[12]。在非临床试验的回顾性报道或基于人口数量进行估算的研究报告中,APL的早期病死率为17%~32%[13]–[18],高危患者的早期病死率为24%~50%[13],[19]–[20],老年患者的早期病死率为23%~50%[14]–[15],[21]–[22]。我们中心的初诊APL患者的早期病死率为8.4%,高危患者的早期病死率为22.4%,老年患者的早期死亡率为19.2%。本研究中初诊APL早期病死率相对较低,除了与治疗经验丰富、注意加强输血支持治疗有关外,还可能因为本研究仅纳入住院患者,一般情况差的患者可能无住院或转院治疗机会。

我们的研究结果提示,年龄≥50岁、WBC≥10×109/L是初诊APL发生早期死亡的独立危险因素。多项研究发现高龄与高白细胞计数是初诊APL早期死亡的危险因素[13]–[15],[22],这与我们的研究结果一致。也有学者报道,PLT降低、LDH升高与APL患者的早期死亡相关[14],[17]。本研究中,PLT在早期死亡患者与非早期死亡患者之间差异无统计学意义。哈尔滨医科大学的学者回顾性分析应用三氧化二砷单药治疗初诊APL患者的早期死亡因素时,发现初诊时PLT与早期死亡无相关性[22]。可能与目前对初诊APL患者实行的积极输血支持治疗,及时纠正血小板减少有关。本研究中,早期死亡患者的LDH明显高于非早期死亡患者,但并非初诊APL早期死亡的独立危险因素。

在本研究中,出血是初诊APL早期死亡的最主要原因,其他死亡原因主要包括感染和分化综合征,与前人的研究结果一致[13]–[14],[22]。在一项大型临床试验中,使用ATRA和IDA诱导治疗的APL患者,9%的患者在诱导过程中死亡,出血是最常见的死亡原因(5%),其次是感染(2.3%)和分化综合征(1.4%)[23]。老年患者早期死亡原因较年轻患者更为复杂,感染或脏器功能衰竭导致死亡的概率较年轻患者更高[14],[21]。

在本研究中,所有患者的OS及DFS良好,与报道结果一致[4],[5],[24]。本研究中,年龄≥50岁患者2年OS率和2年DFS率分别为79.3%和92.3%,与前人的研究结果相符[25],年龄<50岁患者的2年OS率及DFS率分别为94.2%和98.1%。年龄≥50岁既是初诊APL早期死亡的高危因素,对存活患者的预后也有影响。随着年龄的增长,老年患者体能状态差、严重合并症较多,这可能是老年患者早期病死率高、预后差的主要原因。

本研究中,初诊APL患者2年OS率在高危与非高危患者中分别为77.3%和96.7%,2年DFS率均为95%左右。我们的结果表明,初诊时WBC≥10×109/L对患者预后产生不良影响主要在于早期死亡,对非早期死亡患者的预后影响较小。据报道,斯坦福医院收治的初诊APL患者3年OS率在高危、中危、低危患者中分别为56%, 70%,83%,但是非早期死亡患者的3年OS率均在78%以上[13]。这一现象可能与APL治疗的进步、对高危组患者缓解后治疗的强化有关。

综上所述,我们的研究提示初诊APL的早期死亡仍是目前治疗的难点,初诊时年龄≥50岁、WBC≥10×109/L是早期死亡的独立危险因素。初诊APL患者早期死亡的主要原因为出血,老年患者的死亡原因相对复杂,除了积极预防出血,对感染、分化综合征等合并症也需要积极预防救治。老年APL患者的治疗方案仍有探索及优化空间。在APL的诊治过程中,加强对危险因素的重视,采取个体化治疗策略,或许可以获得更好的治疗效果。

Funding Statement

基金项目:江苏省科教强卫工程-临床医学中心资助项目(YXZXA2016002)

Fund program: Funded by The Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Center(YXZXA2016002)

References

- 1.Sanz MA, Fenaux P, Tallman MS, et al. Management of acute promyelocytic leukemia: updated recommendations from an expert panel of the European LeukemiaNet[J] Blood. 2019;133(15):1630–1643. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-01-894980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanz MA, Iacoboni G, Montesinos P. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: do we have a new front-line standard of treatment?[J] Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15(5):445–449. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0339-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts JM, Tallman MS. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: what is the new standard of care?[J] Blood Rev. 2014;28(5):205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iland HJ, Bradstock K, Supple SG, et al. All-trans-retinoic acid, idarubicin, and IV arsenic trioxide as initial therapy in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML4)[J] Blood. 2012;120(8):1570–1580; quiz 1752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-410746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo-Coco F, Avvisati G, Vignetti M, et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic trioxide for acute promyelocytic leukemia[J] N Engl J Med. 2013;369(2):111–121. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanz MA, Tallman MS, Lo-Coco F. Tricks of the trade for the appropriate management of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia[J] Blood. 2005;105(8):3019–3025. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.中华医学会血液学分会, 中国医师协会血液科医师分会. 中国急性早幼粒细胞白血病诊疗指南 (2018年版)[J] 中华血液学杂志. 2018;39(3):179–183. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2727.2018.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cull EH, Altman JK. Contemporary treatment of APL[J] Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2014;9(2):193–201. doi: 10.1007/s11899-014-0205-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fenaux P, Chevret S, Guerci A, et al. Long-term follow-up confirms the benefit of all-trans retinoic acid in acute promyelocytic leukemia. European APL group[J] Leukemia. 2000;14(8):1371–1377. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu H, Hu J, Chen L, et al. The 12-year follow-up of survival, chronic adverse effects, and retention of arsenic in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia[J] Blood. 2016;128(11):1525–1528. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-699439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iland H, Bradstock K, Seymour J, et al. Results of the APML3 trial incorporating all-trans-retinoic acid and idarubicin in both induction and consolidation as initial therapy for patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia[J] Haematologica. 2012;97(2):227–234. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.047506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanz MA, Montesinos P, Vellenga E, et al. Risk-adapted treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia with all-trans retinoic acid and anthracycline monochemotherapy: long-term outcome of the LPA 99 multicenter study by the PETHEMA Group[J] Blood. 2008;112(8):3130–3134. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClellan JS, Kohrt HE, Coutre S, et al. Treatment advances have not improved the early death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemia[J] Haematologica. 2012;97(1):133–136. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.046490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann S, Ravn A, Carlsson L, et al. Continuing high early death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemia: a population-based report from the Swedish Adult Acute Leukemia Registry[J] Leukemia. 2011;25(7):1128–1134. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park JH, Qiao B, Panageas KS, et al. Early death rate in acute promyelocytic leukemia remains high despite all-trans retinoic acid[J] Blood. 2011;118(5):1248–1254. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-346437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altman JK, Rademaker A, Cull E, et al. Administration of ATRA to newly diagnosed patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia is delayed contributing to early hemorrhagic death[J] Leuk Res. 2013;37(9):1004–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciftciler R, Haznedaroglu IC, Aksu S, et al. The Factors Affecting Early Death in Newly Diagnosed APL Patients[J] Open Med (Wars) 2019;14:647–652. doi: 10.1515/med-2019-0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou W, Zhang Y, Jin B, et al. Factors affecting thrombohemorrhagic early death in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with arsenic trioxide alone[J] Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2019;79:102351. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2019.102351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daver N, Kantarjian H, Marcucci G, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with acute promyelocytic leukaemia and hyperleucocytosis[J] Br J Haematol. 2015;168(5):646–653. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehmann S, Deneberg S, Antunovic P, et al. Early death rates remain high in high-risk APL: update from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry 1997-2013[J] Leukemia. 2017;31(6):1457–1459. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lengfelder E, Hanfstein B, Haferlach C, et al. Outcome of elderly patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia: results of the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group[J] Ann Hematol. 2013;92(1):41–52. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1597-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin B, Zhang Y, Hou W, et al. Comparative analysis of causes and predictors of early death in elderly and young patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with arsenic trioxide[J] J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146(2):485–492. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-03076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de la Serna J, Montesinos P, Vellenga E, et al. Causes and prognostic factors of remission induction failure in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with all-trans retinoic acid and idarubicin[J] Blood. 2008;111(7):3395–3402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platzbecker U, Avvisati G, Cicconi L, et al. Improved Outcomes With Retinoic Acid and Arsenic Trioxide Compared With Retinoic Acid and Chemotherapy in Non-High-Risk Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia: Final Results of the Randomized Italian-German APL0406 Trial[J] J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(6):605–612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martínez-Cuadrón D, Montesinos P, Vellenga E, et al. Long-term outcome of older patients with newly diagnosed de novo acute promyelocytic leukemia treated with ATRA plus anthracycline-based therapy[J] Leukemia. 2018;32(1):21–29. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]