Abstract

In the present study, we developed a transcriptomic signature capable of predicting prognosis and response to primary therapy in high grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). Proportional hazard analysis was performed on individual genes in the TCGA RNAseq data set containing 229 HGSOC patients. Ridge regression analysis was performed to select genes and develop multigenic models. Survival analysis identified 120 genes whose expression levels were associated with overall survival (OS) (HR = 1.49-2.46 or HR = 0.48-0.63). Ridge regression modeling selected 38 of the 120 genes for development of the final Ridge regression models. The consensus model based on plurality voting by 68 individual Ridge regression models classified 102 (45%) as low, 23 (10%) as moderate and 104 patients (45%) as high risk. The median OS was 31 months (HR = 7.63, 95% CI = 4.85-12.0, P < 1.0-10) and 77 months (HR = ref) in the high and low risk groups, respectively. The gene signature had two components: intrinsic (proliferation, metastasis, autophagy) and extrinsic (immune evasion). Moderate/high risk patients had more partial and non-responses to primary therapy than low risk patients (odds ratio = 4.54, P < 0.001). We concluded that the overall survival and response to primary therapy in ovarian cancer is best assessed using a combination of gene signatures. A combination of genes which combines both tumor intrinsic and extrinsic functions has the best prediction. Validation studies are warranted in the future.

Keywords: High grade serous ovarian cancer, gene signature, chemotherapy resistance, prognosis, immune evasion, machine learning

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecologic cancer in the United States [1]. The majority of patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage with an estimated 5-year survival between 30% and 50% [2]. Current standard of care consists of cytoreductive surgery either before or after systemic chemotherapy with a combination of a platinum and taxane agents [3]. This regimen is effective at initially treating the cancer, as 80% of patients will have no evidence of disease after therapy completion [4]. However, at least half of patients recur within the first 18 months after therapy [4].

To date, one of the most important prognostic factors for ovarian cancers is the platinum free interval (PFI) defined as the time to recurrence or progression after receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Extended PFIs are associated with higher response rates to repeat platinum treatments and longer survival times [5]. However, a PFI of less than 6 months is considered platinum resistant and is associated with a median survival of 9-12 months [5]. Unfortunately, little is known about platinum resistance or how to overcome it [6].

To better understand the mechanisms of platinum resistance, we applied machine learning to the TCGA RNAseq data to develop multigenic models capable of predicting prognosis and treatment response among high grade serous ovarian cancer patients (HGSOC). Although previous studies have examined prognostic signatures, the reported signatures have below par survival prediction, poor validation in outside datasets, and do not predict platinum resistance [7]. As previous studies have not addressed the significant clinical question of understanding and overcoming platinum resistance [7-14], we undertook the present study to develop a gene signature that can predict both treatment response and survival prognosis.

Methods

Patients and data

TCGA ovarian cancer patient cohort (n = 307) level 3, log2 transformed RNAseq data was obtained through the UCSC Xena platform [15]. Exclusion criteria were unknown stage, grade 1 differentiation, no post-operative treatment, or censored at less than or equal to 6 months. This left a final cohort of 229 patients. Overall survival was the primary endpoint of this study and all surviving patients were censored at 10 years. Of the 229 patients, the median age was 59 and 209 (91.3%) were stage IIIA or later. All patients had serous histology, were grade 2 or higher, underwent primary cytoreductive surgery and received postoperative treatment. An optimal cytoreduction (R0+R1 resections) was achieved in 146 (63.8%) of patients, and most patients had a complete response (n = 136, 59.4%) to initial chemotherapy Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic, pathologic, and treatment information for all patients

| Characteristic | Patients # (%) (n, total = 229) | Median OS | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | < 59 years | 113 (49%) | 49 months | ref | ref |

| ≥ 59 years | 113 (49%) | 38 months | 1.18 (0.85-1.64) | 0.32 | |

| Unknown | 3 (2%) | 24 months | 4.31 (1.34-13.89) | 0.014 | |

| Stage | Low | 20 (9%) | 71 months | ref | 0.06 |

| High* | 209 (91%) | 43 months | 2.20 (0.97-4.99) | ||

| Histology | Serous | 229 (100%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Grade | Moderate | 32 (14%) | 62 months | ref | 0.03 |

| High | 197 (86%) | 42 months | 1.76 (1.07-2.90) | ||

| Lymphovascular Invasion | Negative | 36 (16%) | 52 months | ref | ref |

| Positive | 64 (28%) | 41 months | 1.45 (0.78-2.70) | 0.24 | |

| Unknown | 129 (56%) | 44 months | 1.50 (0.85-2.63) | 0.16 | |

| PDS | Yes | 229 (100%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Residual Disease | R0 | 44 (19%) | 57 months | ref | ref |

| R1 | 102 (44%) | 41 months | 1.82 (1.07-3.09) | 0.03 | |

| R2 | 61 (27%) | 38 months | 1.81 (1.04-3.18) | 0.04 | |

| Unknown | 22 (10%) | 79 months | 0.87 (0.41-1.84) | 0.72 | |

| Treated Postoperatively | Yes | 229 (100%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Response to Primary Treatment | Complete Response | 136 (59%) | 57 months | ref | ref |

| Partial Response | 29 (13%) | 33 months | 4.02 (2.49-6.49) | < 0.001 | |

| No Response | 20 (9%) | 24 months | 5.88 (3.43-10.06) | < 0.001 | |

| Stable Disease | 15 (6%) | 34 months | 2.81 (1.39-5.68) | 0.004 | |

| Unknown | 29 (13%) | 32 months | 4.00 (2.42-6.63) | < 0.001 | |

Abbreviations: HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, Low Stage IIA-IIC, High Stage IIIA-IV, High grade: cancers described as grade 3, Moderate Grade: cancers described as grade 2, R0 No residual disease, R1 between 1 mm - 10 mm of residual disease, R2 greater than 10 mm of residual disease, PDS: primary debulking surgery.

Among high stage patients 170 (81%) and 22 (11%) were stage IIIC and IV, respectively.

Survival analyses with individual genes

All statistical analyses were performed using the R language and environment for statistical computing [16]. Genes with an even distribution of patients when divided into 4 quartiles were chosen for analysis (n = 14,262). In single gene analyses, patients were ranked by expression levels and divided into four quartiles. The first quartile was used as the reference and compared to the 2nd, 3rd and 4th quartiles using Cox proportional hazards for survival analyses. All survival analyses and Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using the “survival package” in R [17].

Ridge regression

Ridge regression was carried out with different gene sets to calculate Ridge Regression Scores (RRS) for each patient using the “glmnet” package in R [18]. Ridge regression combines multiple inputs in a linear manner and then uses a penalty term (lambda) to tune the model. The effect of this penalty term can be modified to have no effect (lambda = 0) or if lambda equals infinity the coefficient of the input parameter equals 0, meaning the given parameter has no impact on the model. The input factors are then summed together based on their coefficients resulting in an individual score for each patient. The lambda value was optimized using the lambda.min function, which automatically chooses the lambda which results in the least errors on cross validation. After the RRS is computed for each patient, all patients were ranked and then divided into two groups (RRS_high and RRS_low) by the cumulative sum of their RRS. Survival for the low and high RRS groups were then compared by Cox Proportion hazard analysis.

The analytical pipeline incorporated training and testing component for each step. Briefly, the 229 patients were randomly divided into a training subset and a testing subset, each with 50% of the total number of patients. This process is repeated 3,000 times to generate 3,000 pairs of training/testing datasets. Ridge regression was performed and RRS calculated for each patient in each training set and survival was assessed for RRS_high versus RRS_low groups using the median RRS cutoff. The same median cutoff derived from the training dataset was applied to the corresponding testing dataset for survival analyses. The pipeline generated a table that contains hazard ratio (HR) and p-value for both training and testing datasets for all 3000 iterations (or models). The pipeline also calculated the relative contribution of each gene in the dataset to each model, allowing us to assess the importance of all investigated genes.

Validation by bootstrapping

Bootstrapping was used to perform further validation and estimate the mean and 95% confidence interval for the HR associated with each model. Briefly, 70% of patients were randomly sampled for each bootstrap and 1,000 bootstraps with replacement were generated for this study. Each bootstrapped dataset, for the selected top models were analyzed by Ridge regression and Cox proportion Hazard. The mean HR from all 1000 bootstraps was also computed and the 95% confidence interval was defined by the HR at the 5th and 95th percentiles of the 1000 models. Conventionally, models are considered validated if 95% or more models have p values less than 0.05.

Plurality voting for consensus modeling

Our analytical pipeline generated a number of models that were validated by training, testing, and bootstrapping. It was critical to assess the consistency of patient classification by each of the selected models. For this purpose, the RRS group assignment for each patient by the selected models was compiled and the percentages of models assigning a specific patient to each RRS group were calculated. If 75% or greater of the models assigned a patient as high or low RRS group, the patient was considered confidently classified in their respective risk group. A patient was assigned to an “ambiguous” or “moderate” RRS group if less than 75% of the models assigned the patient to neither the low nor the high RRS groups. This plurality voting of multiple models was used as the final classification of the patients and was expected to be more robust than any individual model.

Gene/protein interaction analysis

Gene function was evaluated using the public database GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) [19]. Gene/protein interaction was deciphered by using STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins) v11 which is a publicly available database (https://string-db.org/) [20].

Results

Survival analyses with single genes

As expected, univariate analysis indicated that grade and residual disease were only marginally predictive of overall survival while treatment response was a good predictor of survival (Table 1). Cox proportional hazard analysis of 14,262 genes revealed 881 genes (6.2%) with some prognostic value for overall survival when analyzed as a continuous variable (P < 0.05). The top 120 genes were selected using a combination of gene function, HR between the fourth and first quartile, and level of significance (Supplementary Table 1). However, even among the best genes, there was no individual gene with an HR greater than 2.5, demonstrating that individual genes alone have minimal predictive capability for ovarian cancer prognosis.

Ridge regression models have excellent prognostic potential

Given the limited predictive ability of individual genes, Ridge regression was then used to see if combination of genes could outperform individual genes. In contrast to the conventional approach that would try to generate one Ridge regression model using the entire dataset of 229 patients, we developed an analytic pipeline, as defined in the methods, that generates and tests large numbers of models to identify the best-performing and robust models. This method allowed for the generation 3,000 models. The best models were defined as those having excellent survival differences between low and high RRS groups in both the training and testing subsets. This pipeline was initially applied to the previously defined 120 genes, which yielded 40 models with HR > 4.0 in the training/testing pairs. To further reduce the number of genes and focus only on the best performing genes, we computed the relative contribution of each gene for individual models. Then we used the average contribution of individual genes of the best performing models to rank all 120 genes. At the end, we selected a 38 gene signature for subsequent studies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival analysis and function of the 38 genes determined to be part of the final gene signature (38-OG) and their functions

| Gene | Q4_HR (95% CI) | Q4_p | *RRS in 38 | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UBE2J1 | 0.63 (0.40-0.99) | 4.37E-02 | -0.091 | Targets misfolded MHC class I proteins for degradation [21] |

| C1orf74 | 0.56 (0.35-0.88) | 1.28E-02 | -0.081 | Unknown function |

| CLEC6A | 0.45 (0.28-0.73) | 1.33E-03 | -0.081 | Stimulate dendritic cells and T-cells [22,23] |

| BTLA | 0.54 (0.34-0.87) | 1.01E-02 | -0.067 | Dual role in prolonging T-cell survival but also can depress T-cell response [24,25] |

| XBP1 | 0.48 (0.3-0.77) | 2.43E-03 | -0.066 | Promote Th2 expansion, and NK cell response [26,27] |

| TRIM27 | 0.62 (0.39-0.99) | 4.29E-02 | -0.065 | Positive regulation of TNF-alpha induced apoptosis, interferon gamma production [28,29] |

| EIF4E3 | 0.53 (0.33-0.86) | 1.03E-02 | -0.062 | Involved in the innate immune system pathway and interferon gamma signaling [30] |

| MON1A | 0.52 (0.33-0.84) | 7.57E-03 | -0.060 | Membrane trafficking via the secretory pathway not lysosomal route [31] |

| SOCS2 | 0.56 (0.35-0.9) | 1.64E-02 | -0.060 | Important for T-helper cell type 1 function [32] |

| GMPPB | 0.58 (0.36-0.92) | 2.12E-02 | -0.059 | Catalyzes the formation of essential glycan precursors. Glycans are essential for immune function [31,33] |

| LRRC45 | 0.56 (0.35-0.9) | 1.61E-02 | -0.056 | Part of centrosome construction [34] |

| LCK | 0.70 (0.43-1.12) | 1.36E-01 | -0.055 | Involved in selection and maturation of T cells [35] |

| UBB | 0.56 (0.35-0.9) | 1.62E-02 | -0.055 | Stimulate apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway, tag proteins for degradation, DNA repair [30,36] |

| FBF1 | 0.53 (0.32-0.86) | 9.62E-03 | -0.054 | Required for epithelial cell polarization and centrosome formation [37] |

| CLPTM1L | 0.67 (0.42-1.07) | 9.21E-02 | -0.048 | Involved in stimulating apoptosis in response to DNA damage [38] |

| MLLT4 | 1.18 (0.73-1.89) | 5.05E-01 | -0.048 | Tumor suppressor function [39] |

| SHISA5 | 0.64 (0.4-1.02) | 6.30E-02 | -0.047 | With p53 induces apoptosis in caspase dependent manner [40] |

| CYP2R1 | 0.71 (0.45-1.11) | 1.31E-01 | -0.045 | Important for Vitamin D production, which is associated with natural killer cell function [41,42] |

| SPEN | 1.50 (0.94-2.39) | 9.11E-02 | -0.037 | Cell cycle regulation [43] |

| ME1 | 0.56 (0.35-0.91) | 1.83E-02 | -0.034 | Role in bacterial response [44] |

| SOCS5 | 1.49 (0.93-2.38) | 9.71E-02 | 0.035 | Inhibit dendritic cell function [45] |

| EMP1 | 1.76 (1.11-2.81) | 1.63E-02 | 0.037 | Promotes proliferation and cell survival [46] |

| AGFG1 | 1.69 (1.08-2.64) | 2.06E-02 | 0.053 | circularRNA form promotes proliferation, metastasis, and increased cyclin expression E expression (known contributor to platinum resistance) [47-49] |

| METTL1 | 0.86 (0.53-1.38) | 5.30E-01 | 0.055 | Promotes cell proliferation and migration [50] |

| TSPAN9 | 1.65 (1.03-2.64) | 3.62E-02 | 0.057 | Promotes autophagy [51] |

| PYGM | 1.7 (1.08-2.7) | 2.33E-02 | 0.058 | Increases glycogen usage especially in muscles that do not utilize oxygen [52] |

| VPS24 | 1.75 (1.11-2.77) | 1.66E-02 | 0.061 | Promotes autophagy [53] |

| PYGB | 1.95 (1.23-3.09) | 4.27E-03 | 0.062 | Role in promoting growth under hypoxic conditions [54] |

| CCDC144C | 2.08 (1.29-3.35) | 2.48E-03 | 0.063 | Psuedogene, expression has been associated with paclitaxel resistance [55] |

| ANGPT4 | 1.83 (1.15-2.94) | 1.14E-02 | 0.078 | Promote vascular growth and recruitment of fibroblasts [56] |

| WWP1 | 1.49 (0.93-2.4) | 9.58E-02 | 0.078 | Promote proliferation, involved in autophagy [57] |

| RPL23P8 | 1.72 (1.09-2.71) | 2.07E-02 | 0.079 | Ribosomal Function Protein (Psuedogene) [30] |

| PEX3 | 1.87 (1.13-3.09) | 1.43E-02 | 0.083 | Promotes autophagy [58] |

| SUSD5 | 2.09 (1.3-3.36) | 2.22E-03 | 0.083 | Promotes proliferation and metastasis [59] |

| STAC2 | 2.46 (1.5-4.04) | 3.61E-04 | 0.088 | Promotes cell membrane transport activity [31] |

| KIAA1033 | 1.66 (1.04-2.65) | 3.33E-02 | 0.090 | Role in promoting growth under hypoxic conditions [54] |

| PI3 | 1.52 (0.98-2.35) | 6.06E-02 | 0.091 | Involved in proliferation and survival [60] |

| CALML3 | 2.00 (1.27-3.17) | 2.91E-03 | 0.105 | Promotes cell proliferation metastasis [61] |

*Q4 is the fourth quartile, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval;

RRS in 38 refers to the ridge regression coefficient for each gene as determined by the 68 best models.

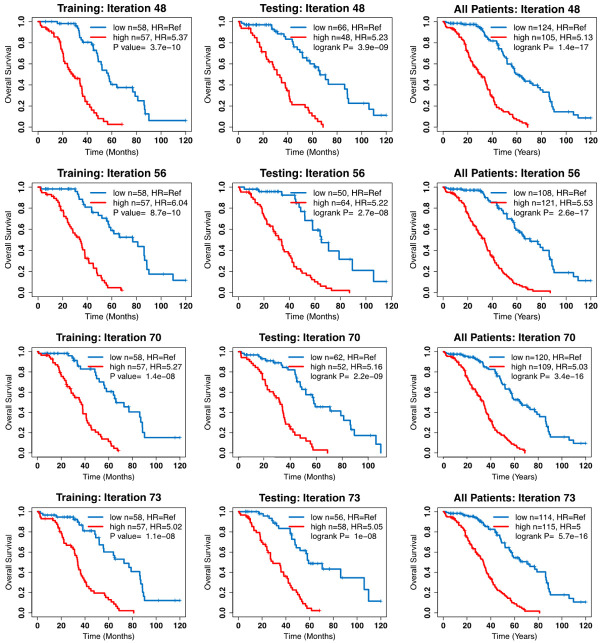

Ridge regression was then repeated utilizing data on the 38 genes in the 3,000 training and test pairs. This resulted in 68 different models that had an HR of greater than 5 in both the training and test sets (Table 3). The mean ridge regression scores for each of the 38 genes is shown in Table 2. Kaplan-Meier curves for select models are shown in Figure 1. On covariable analysis including clinical factors and Ridge regression score (RRS), only treatment response and RRS were consistently associated with patient prognosis (P < 0.001), while grade was only significantly associated with prognosis in 7 of the 68 (10.2%) models, and residual disease was never significantly associated with patient prognosis Supplementary Table 2. Because of the size of the dataset, there were not enough patients to have a holdout set of samples for cross validation of these models. Therefore, bootstrapping was employed to assess the validity of the models. All models had a p-value of 1×10-6 or less after bootstrapping, demonstrating that these models reliably predict patient prognosis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Survival Analysis for 68 best Ridge regression models from the 38-gene signature

| Model# | Training and Testing | Entire Data Set | Bootstrapping (1000) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Train HR (CI) | Train P | Test HR (CI) | Test P | HR (CI) | P-value | Mean HR (CI) | P < 1E-6* | P < 1E-10* | |

| 48 | 5.37 (3.18-9.09) | 3.74E-10 | 5.23 (3.01-9.07) | 3.94E-09 | 5.13 (3.52-7.47) | 1.4E-17 | 4.44 (3.37-6.04) | 240 | 760 |

| 56 | 6.04 (3.4-10.7) | 8.69E-10 | 5.22 (2.91-9.35) | 2.74E-08 | 5.53 (3.72-8.21) | 2.55E-17 | 5.21 (3.93-6.94) | 19 | 981 |

| 70 | 5.27 (2.97-9.37) | 1.44E-08 | 5.16 (3.02-8.84) | 2.19E-09 | 5.03 (3.41-7.41) | 3.38E-16 | 4.91 (3.84-6.43) | 109 | 891 |

| 73 | 5.02 (2.89-8.72) | 1.07E-08 | 5.05 (2.9-8.78) | 1.03E-08 | 5 (3.39-7.38) | 5.66E-16 | 5.2 (4.02-6.69) | 37 | 963 |

| 81 | 5.25 (2.99-9.24) | 8.29E-09 | 6.46 (3.62-11.5) | 2.75E-10 | 5.71 (3.83-8.52) | 1.28E-17 | 5.76 (4.31-7.65) | 4 | 996 |

| 129 | 5.61 (3.39-9.29) | 2.09E-11 | 5.66 (3.08-10.4) | 2.40E-08 | 5.56 (3.78-8.19) | 3.27E-18 | 5.3 (4.06-6.95) | 27 | 973 |

| 166 | 5.27 (2.98-9.31) | 1.13E-08 | 5.93 (3.44-10.2) | 1.44E-10 | 5.27 (3.59-7.76) | 2.76E-17 | 4.94 (3.76-6.79) | 67 | 933 |

| 235 | 5.91 (3.26-10.7) | 5.25E-09 | 5.4 (2.94-9.95) | 5.99E-08 | 5.7 (3.72-8.73) | 1.31E-15 | 5.1 (3.77-6.75) | 84 | 916 |

| 281 | 5.34 (3.02-9.44) | 7.93E-09 | 5.06 (3-8.51) | 1.07E-09 | 4.93 (3.37-7.2) | 1.71E-16 | 4.77 (3.65-6.34) | 102 | 898 |

| 305 | 5.17 (3.01-8.9) | 2.91E-09 | 5 (2.94-8.51) | 2.87E-09 | 5.15 (3.53-7.51) | 2.13E-17 | 5.5 (4.28-7.18) | 6 | 994 |

| 429 | 6.23 (3.52-11) | 3.24E-10 | 5.07 (2.69-9.53) | 4.86E-07 | 5.24 (3.47-7.93) | 3.98E-15 | 4.79 (3.7-6.4) | 96 | 904 |

| 530 | 5.66 (3.15-10.2) | 6.84E-09 | 5.17 (3.07-8.73) | 7.35E-10 | 5.33 (3.63-7.84) | 1.71E-17 | 4.78 (3.69-6.24) | 149 | 851 |

| 550 | 6.53 (3.68-11.6) | 1.49E-10 | 5.4 (3.03-9.62) | 1.03E-08 | 6.03 (4.01-9.07) | 5.22E-18 | 5.53 (4.26-7.22) | 4 | 996 |

| 594 | 5.54 (3.2-9.6) | 9.81E-10 | 5.7 (3.24-10) | 1.62E-09 | 5.62 (3.79-8.32) | 7.47E-18 | 5.42 (3.84-7.22) | 45 | 955 |

| 596 | 6.7 (3.77-11.9) | 8.18E-11 | 5.04 (2.93-8.67) | 5.09E-09 | 5.73 (3.88-8.46) | 1.82E-18 | 5.49 (4.15-7.16) | 9 | 991 |

| 725 | 5.03 (2.89-8.74) | 9.88E-09 | 5.14 (2.79-9.49) | 1.64E-07 | 4.52 (3.07-6.65) | 1.93E-14 | 4.34 (3.43-5.45) | 228 | 772 |

| 744 | 5.34 (2.99-9.54) | 1.49E-08 | 5.1 (2.9-8.96) | 1.59E-08 | 5.21 (3.49-7.8) | 9.05E-16 | 5.11 (3.97-6.56) | 30 | 970 |

| 833 | 6.38 (3.6-11.3) | 2.00E-10 | 5.1 (2.87-9.05) | 2.68E-08 | 5.69 (3.81-8.49) | 2.14E-17 | 5.44 (4.23-6.98) | 8 | 992 |

| 844 | 5.79 (3.34-10.1) | 4.31E-10 | 5.38 (3.04-9.53) | 7.77E-09 | 5.55 (3.74-8.24) | 1.76E-17 | 5.49 (4.3-7.16) | 8 | 992 |

| 899 | 5.04 (2.94-8.65) | 4.35E-09 | 5.99 (3.3-10.9) | 3.99E-09 | 5.3 (3.57-7.87) | 1.11E-16 | 5.21 (4.06-6.63) | 13 | 987 |

| 923 | 5.83 (3.28-10.4) | 1.87E-09 | 5.91 (3.28-10.6) | 3.22E-09 | 5.48 (3.69-8.14) | 2.98E-17 | 5 (3.87-6.69) | 43 | 957 |

| 924 | 5.23 (2.99-9.13) | 6.07E-09 | 6.86 (3.81-12.3) | 1.26E-10 | 5.78 (3.88-8.62) | 6.47E-18 | 5.66 (4.16-7.65) | 13 | 987 |

| 1005 | 5.25 (3.07-9) | 1.52E-09 | 5.11 (2.95-8.86) | 6.37E-09 | 4.95 (3.41-7.19) | 3.98E-17 | 4.61 (3.53-6.38) | 148 | 852 |

| 1042 | 5.35 (3.06-9.33) | 3.71E-09 | 5.17 (2.94-9.07) | 1.05E-08 | 5.3 (3.57-7.87) | 1.54E-16 | 5.23 (3.97-6.78) | 33 | 967 |

| 1046 | 5.04 (2.91-8.72) | 7.64E-09 | 5.56 (3.19-9.69) | 1.46E-09 | 5.03 (3.43-7.36) | 1.01E-16 | 5.14 (3.93-6.63) | 27 | 973 |

| 1079 | 5.12 (2.87-9.11) | 2.94E-08 | 5.1 (2.98-8.75) | 3.03E-09 | 4.84 (3.27-7.15) | 2.46E-15 | 4.87 (3.85-6.31) | 74 | 926 |

| 1128 | 5.31 (3.09-9.13) | 1.53E-09 | 5.3 (2.98-9.45) | 1.46E-08 | 5.47 (3.68-8.12) | 4.06E-17 | 5.34 (4.06-7) | 17 | 983 |

| 1176 | 6.9 (3.87-12.3) | 5.85E-11 | 5 (2.95-8.48) | 2.30E-09 | 5.54 (3.8-8.09) | 6.71E-19 | 4.71 (3.57-6.31) | 111 | 889 |

| 1253 | 6.21 (3.54-10.9) | 1.82E-10 | 5.29 (2.95-9.49) | 2.34E-08 | 5.66 (3.8-8.45) | 1.98E-17 | 5.18 (3.85-6.88) | 30 | 970 |

| 1293 | 5.16 (3-8.88) | 3.01E-09 | 5.21 (2.95-9.19) | 1.31E-08 | 5.11 (3.47-7.52) | 1.42E-16 | 4.64 (3.58-6.14) | 109 | 891 |

| 1352 | 5.68 (3.28-9.84) | 5.75E-10 | 5.56 (3.09-10) | 1.07E-08 | 5.71 (3.82-8.53) | 2.04E-17 | 5.52 (4.17-7.05) | 9 | 991 |

| 1506 | 5.29 (3.03-9.25) | 5.02E-09 | 6.13 (3.43-10.9) | 8.25E-10 | 5.15 (3.5-7.57) | 9.23E-17 | 4.78 (3.57-6.67) | 153 | 847 |

| 1561 | 6.39 (3.44-11.9) | 4.39E-09 | 5.6 (3.25-9.65) | 5.50E-10 | 5.97 (3.97-8.98) | 8.38E-18 | 5.8 (4.34-7.77) | 1 | 999 |

| 1569 | 5.3 (3.1-9.05) | 9.79E-10 | 5.68 (3.15-10.2) | 7.76E-09 | 5.41 (3.65-8.03) | 5.39E-17 | 5.18 (3.98-6.77) | 38 | 962 |

| 1589 | 5.2 (2.98-9.07) | 6.04E-09 | 6.09 (3.46-10.7) | 3.88E-10 | 5.55 (3.74-8.23) | 1.71E-17 | 5.27 (4.11-6.91) | 13 | 987 |

| 1623 | 10.9 (5.37-22.1) | 3.59E-11 | 5.18 (2.68-10) | 9.79E-07 | 6.26 (4.03-9.72) | 2.97E-16 | 5.55 (4.36-7.23) | 10 | 990 |

| 1639 | 5.11 (3.05-8.59) | 6.80E-10 | 6.14 (3.33-11.3) | 6.35E-09 | 5.59 (3.77-8.29) | 1.1E-17 | 5.41 (3.99-7.21) | 33 | 967 |

| 1657 | 5.29 (3.05-9.17) | 2.93E-09 | 5.51 (3.14-9.66) | 2.67E-09 | 5.28 (3.58-7.78) | 4.08E-17 | 5.29 (4.09-7.19) | 11 | 989 |

| 1684 | 5.49 (3.09-9.74) | 5.98E-09 | 5.21 (2.95-9.2) | 1.30E-08 | 4.83 (3.29-7.08) | 8.37E-16 | 4.85 (3.74-6.57) | 93 | 907 |

| 1701 | 5.19 (2.92-9.24) | 2.16E-08 | 5.4 (3.22-9.05) | 1.66E-10 | 4.98 (3.43-7.24) | 4.09E-17 | 5.96 (4.36-8.07) | 5 | 995 |

| 1719 | 5.77 (3.38-9.85) | 1.32E-10 | 5.07 (2.87-8.94) | 2.21E-08 | 5.44 (3.69-8.03) | 1.42E-17 | 5.35 (4.15-6.97) | 13 | 987 |

| 1758 | 5.49 (3.15-9.58) | 2.03E-09 | 5.43 (3.06-9.62) | 7.00E-09 | 5.51 (3.7-8.21) | 4.02E-17 | 5.37 (4.09-6.94) | 24 | 976 |

| 1818 | 5.49 (3.22-9.35) | 3.69E-10 | 5.58 (3.18-9.78) | 2.05E-09 | 5.51 (3.75-8.11) | 3.98E-18 | 5.27 (4.18-6.64) | 11 | 989 |

| 1822 | 5.18 (3.05-8.8) | 1.22E-09 | 6.08 (3.31-11.2) | 6.34E-09 | 5.46 (3.67-8.11) | 5.27E-17 | 4.99 (3.85-6.53) | 58 | 942 |

| 1864 | 6.22 (3.63-10.7) | 2.67E-11 | 5.59 (3.08-10.1) | 1.45E-08 | 5.44 (3.69-8.02) | 1.19E-17 | 5.44 (4.32-7.1) | 3 | 997 |

| 1878 | 5.74 (3.28-10) | 8.91E-10 | 5.35 (3.06-9.34) | 3.66E-09 | 5.53 (3.74-8.16) | 8.05E-18 | 5.31 (3.98-6.97) | 18 | 982 |

| 1999 | 5.04 (3-8.47) | 9.81E-10 | 5.07 (2.86-8.98) | 2.57E-08 | 4.98 (3.4-7.29) | 1.51E-16 | 4.83 (3.62-6.44) | 108 | 892 |

| 2064 | 6.92 (4.02-11.9) | 2.80E-12 | 5.39 (2.86-10.2) | 1.90E-07 | 5.92 (3.93-8.9) | 1.45E-17 | 5.78 (4.34-7.8) | 6 | 994 |

| 2065 | 6.68 (3.78-11.8) | 6.70E-11 | 5.08 (2.87-8.99) | 2.46E-08 | 5.63 (3.77-8.39) | 2.37E-17 | 5.37 (4.15-6.85) | 16 | 984 |

| 2066 | 5.54 (3.22-9.55) | 6.72E-10 | 5.85 (3.07-11.2) | 8.10E-08 | 5.41 (3.6-8.14) | 4.46E-16 | 5.28 (4.03-6.79) | 24 | 976 |

| 2090 | 5.27 (3.05-9.1) | 2.64E-09 | 5.35 (2.96-9.66) | 2.74E-08 | 5.31 (3.58-7.88) | 1.1E-16 | 5.25 (4.04-7.06) | 16 | 984 |

| 2125 | 5.68 (3.16-10.2) | 7.04E-09 | 5.56 (3.21-9.63) | 1.01E-09 | 4.98 (3.4-7.27) | 1.14E-16 | 4.97 (3.75-6.57) | 66 | 934 |

| 2136 | 5.13 (2.93-8.97) | 9.66E-09 | 5.13 (2.81-9.37) | 1.03E-07 | 4.98 (3.33-7.47) | 7.07E-15 | 4.93 (3.74-6.52) | 74 | 926 |

| 2206 | 6.6 (3.73-11.7) | 8.59E-11 | 5.18 (2.82-9.52) | 1.14E-07 | 5.02 (3.37-7.47) | 1.65E-15 | 4.8 (3.77-6.14) | 57 | 943 |

| 2267 | 5.44 (3.18-9.32) | 6.91E-10 | 5.42 (3.03-9.7) | 1.26E-08 | 4.84 (3.33-7.03) | 1.3E-16 | 4.66 (3.48-6.56) | 162 | 838 |

| 2278 | 5.32 (3.04-9.3) | 4.66E-09 | 5.32 (3.08-9.17) | 1.87E-09 | 5.36 (3.63-7.9) | 2.61E-17 | 5.26 (4.01-7.03) | 28 | 972 |

| 2298 | 5.19 (3.04-8.84) | 1.42E-09 | 5.1 (2.98-8.73) | 2.63E-09 | 4.95 (3.43-7.15) | 1.36E-17 | 5.09 (3.95-6.6) | 25 | 975 |

| 2342 | 5.06 (2.98-8.6) | 2.03E-09 | 5.12 (3.02-8.69) | 1.34E-09 | 5.01 (3.46-7.26) | 1.77E-17 | 4.79 (3.74-6.1) | 56 | 944 |

| 2346 | 5.31 (3.12-9.04) | 7.67E-10 | 5.01 (2.86-8.76) | 1.68E-08 | 5.21 (3.55-7.66) | 4.66E-17 | 5.06 (3.94-6.6) | 36 | 964 |

| 2423 | 5.05 (3.07-8.31) | 1.93E-10 | 5.05 (2.92-8.75) | 7.08E-09 | 4.9 (3.42-7.04) | 6.55E-18 | 5.26 (4.04-6.85) | 16 | 984 |

| 2509 | 5.17 (2.95-9.06) | 9.32E-09 | 5.31 (3.04-9.25) | 3.92E-09 | 5.14 (3.48-7.58) | 1.88E-16 | 5.31 (3.97-7.12) | 30 | 970 |

| 2553 | 5.4 (3.14-9.3) | 1.17E-09 | 5.26 (2.99-9.24) | 7.94E-09 | 5.32 (3.61-7.84) | 3.33E-17 | 5.56 (4.32-7.38) | 6 | 994 |

| 2576 | 7.49 (4.07-13.8) | 9.67E-11 | 6.61 (3.3-13.2) | 1.03E-07 | 5.79 (3.81-8.8) | 2.09E-16 | 4.63 (3.51-6.22) | 195 | 805 |

| 2635 | 5 (2.87-8.7) | 1.23E-08 | 5.84 (3.28-10.4) | 1.93E-09 | 5.3 (3.56-7.88) | 1.88E-16 | 5.05 (3.79-6.66) | 69 | 931 |

| 2764 | 5.12 (2.95-8.88) | 6.15E-09 | 5.07 (2.91-8.83) | 1.02E-08 | 5.19 (3.51-7.69) | 1.76E-16 | 5.37 (3.99-7.39) | 35 | 965 |

| 2868 | 5.11 (2.94-8.89) | 7.92E-09 | 5.16 (3.04-8.74) | 1.07E-09 | 5.02 (3.46-7.3) | 2.42E-17 | 5.14 (3.92-7.04) | 25 | 975 |

| 2869 | 5.45 (3.24-9.17) | 1.58E-10 | 5 (2.88-8.68) | 1.04E-08 | 4.93 (3.41-7.13) | 2.11E-17 | 5.06 (3.88-6.81) | 34 | 966 |

| 2954 | 5.36 (3.04-9.44) | 6.00E-09 | 6.53 (3.34-12.8) | 4.36E-08 | 5.98 (3.89-9.2) | 3.47E-16 | 5.5 (4.18-7.38) | 15 | 985 |

HR (Hazard Ratio), CI (95% Confidence Interval);

The number of models out of 1,000 bootstraps with a p-value < 1E-6 (between 1E-6 and 1E-10) or < 1E-10, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan Meier survival curves for 4 of the 68 models which had a HR of greater than 5 in both the training and testing datasets.

Consensus modeling provides superior and robust survival prediction

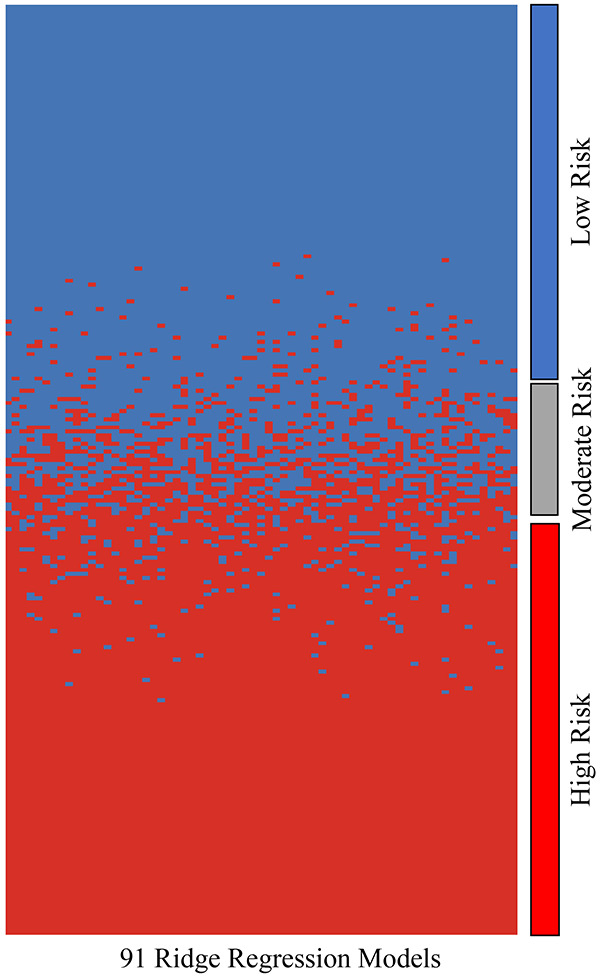

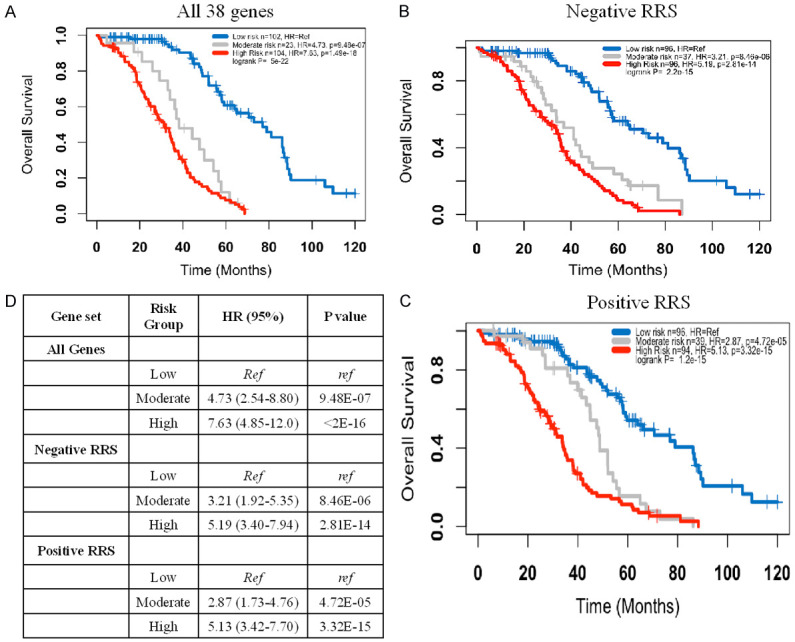

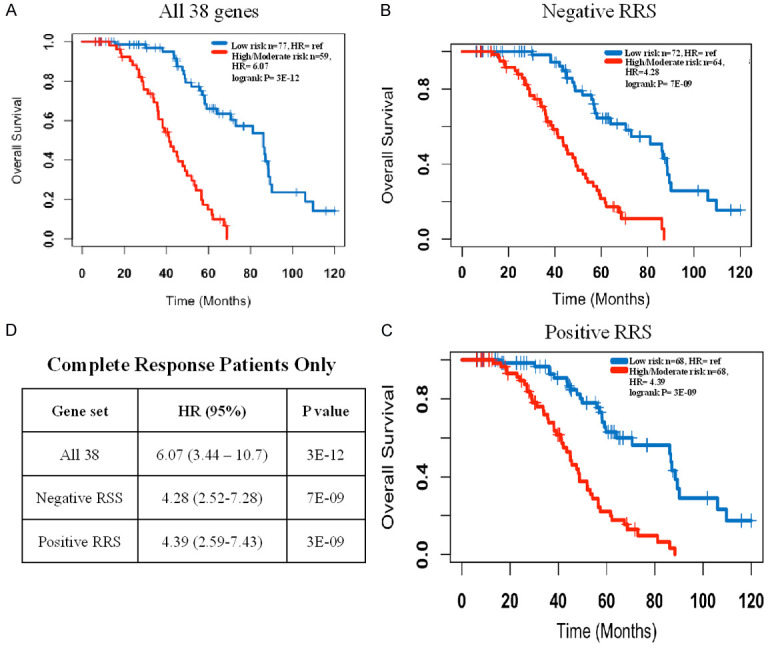

Although each of the 68 models has excellent prognostic power, it is not expected that every model assigns every patient to the same risk group. Therefore, it was critical to assess the consistency of the models in classifying individual patients. A heatmap was generated that shows the group assignment of each of the 229 patients by each of the 68 models Figure 2. Overall, the 68 models classified the majority of the patients in a highly consistent manner, as such, 102 of the 229 patients were classified into the low risk group by more than 75% of the models, 104 other patients were classified in the high risk group by more than 75% of the models, and only 23 patients did not have a supermajority (> 75%) of the votes and were considered as a moderate risk group. Survival analysis using these three consensus or plurality voting groups revealed that the high risk group had a median overall survival of 31 months compared to 77 months for the low risk group (HR = 7.63, 95% CI = 4.85-12.0, P < 1E-10). The intermediate risk group had a median overall survival of 38 months (HR = 4.73, 95% CI = 2.54-8.80, P < 1E-5) (Figure 3A). The moderate risk and high risk groups were combined together in subsequent analyses. When survival analysis was restricted to the 136 patients who had complete response, the high/moderate risk group has a much shorter median overall survival (41 months) than the low risk group (86 months) (HR = 6.07, 95% CI = 3.44-10.7, P < 1E-10) (Figure 4A).

Figure 2.

Heat map comparing how each model (columns) ranked each patient in terms of risk (high or low). For the most part, each model agreed on whether patients were low or high risk. If there was greater than 25% disagreement between all models on whether a patient was high or low risk, that patient was categorized as moderate risk. Patients were ordered by the percentage of votes for the high risk group (red color).

Figure 3.

Kaplan Meier curve for the entire dataset. A. Models using all 38 genes; B. Models using the 20 of the 38 genes that have mainly lower expression in the high risk group and HR < 1 (mostly immune genes); C. Models using the 18 of the 38 genes that have mainly higher expression in the high risk group and HR > 1 (mostly tumor intrinsic genes); D. Summary statistics.

Figure 4.

Kaplan Meier curve for the complete response patients only. High and intermediate risk groups were combined into one group. A. Models using all 38 genes; B. Models using the 20 of the 38 genes that have mainly lower expression in the high risk group and HR < 1 (mostly immune genes); C. Models using the 18 of the 38 genes that have mainly higher expression in the high risk group and HR > 1 (mostly tumor intrinsic genes); D. Summary statistics.

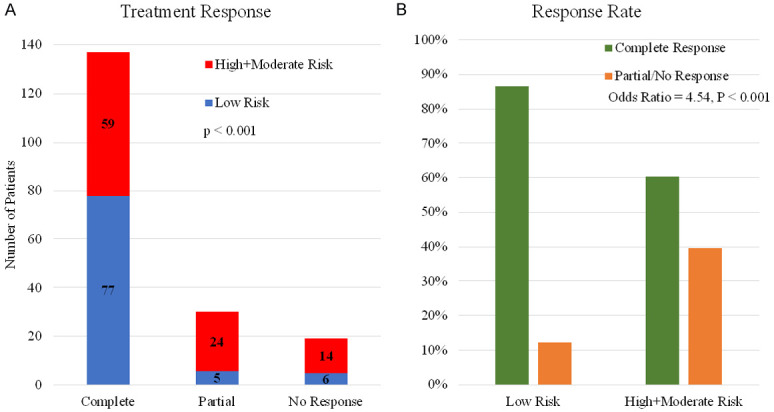

Risk group designation is predictive of therapy response

As shown in Table 1, response to primary therapy was predictive of overall survival. As expected, patients with complete response had the best survival with a median overall survival of 57 months, while median overall survival was shorter for partial responders (33 months, HR = 4.02, P < 0.001) and non-responders (24 months and HR = 5.88, P < 0.001). We examined whether the 38-gene transcriptomic signature was predictive of response to primary therapy in these three groups after excluding patients with unknown or stable disease. As shown in Figure 5A, 77 of the 136 (57%) complete responders were classified as “low risk” by the consensus Ridge model, while 24 of 29 (83%) partial responders and 14 of 20 (70%) non-responders were classified as high/moderate risk. Indeed, only 12% of the low risk patients did not have a complete response, while 40% of the high/moderate risk patients did not have a complete response (odds ratio = 4.54, P < 0.001) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Comparison of treatment response between the low and intermediate/high risk groups. Patients who had an unknown response or stable disease were omitted from this analysis given the uncertainty surrounding these terms. A. Distribution of risk groups in subset of patients with different response to chemotherapy. B. Response rate in low versus high/intermediate risk groups determined by the 38-gene consensus model.

Function and pathway of the 38-gene signature

The potential function of the 38 genes in relation to cancer patient survival was examined through searches in public databases such as PubMed, Genecards, and STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins). The most prominent biological actions included immune function and regulation, cell proliferation and apoptosis, DNA repair, glycan production and glycan binding, and endosome-related functions (Table 2). STRING analysis highlighted endosomal transport (P = 0.004) as the most significant biological process and endocytosis (P = 0.001) as the most important molecular pathway (Supplementary Table 3).

Although it is not identified by STRING analysis, 12 of the 20 genes (UBE2J1, CLEC6A, BTLA, XBP1, TRIM27, EIF4E3, SCOS2, GMPPB, LCK, UBB, CYP2R1, ME1) that had negative mean RRS were associated with immune function and/or regulation (extrinsic tumor components) (Table 2). These 20 genes alone possess very good prognostic power for the entire dataset (Figure 3B) as well as the subset with complete response to chemotherapy (Figure 4B). In contrast to the function of genes with a negative RRS, genes with positive RRS scores were mainly associated tumor intrinsic characteristics such as cell proliferation, metastasis, and autophagy (Table 2). Again, even these positive mean RSS genes alone showed excellent prognostic prediction across the entire dataset (Figure 3C) and in only those patients with a complete response to primary therapy (Figure 4C).

To further elucidate the molecular and functional mechanisms underlying the differential survival, we conducted a differential expression analysis between RRS high and low patients, consisting of the genes with at least two-fold or higher expression change between groups. Table 4 shows two distinct groups of differentially expressed genes, consistent with the previously mentioned intrinsic and extrinsic groups. One is a group of 26 genes that have lower expression in the high risk group and the second, a group of 18 genes, with higher expression in the high risk group. All 26 genes with lower expression in high risk patients are implicated in immune function, while the genes with higher expression in high risk patients have functions related to cell proliferation and survival, migration, and chemotherapy resistance (Table 4). This further supports the idea of a tumor extrinsic and tumor intrinsic component of our genetic risk score.

Table 4.

Genes with a 2-fold or greater expression difference between the high/moderate and low risk groups

| Overexpressed Genes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gene | High Risk Mean Expression | Low Risk Mean Expression | * p-value | *Fold Change | AUC | Function |

|

| ||||||

| IGF2 | 14.18 | 11.78 | 3.40E-07 | 5.28 | 0.70 | Increase cell proliferation and support survival, potentiate chemotherapy resistance [62,63] |

| SOX11 | 6.12 | 4.08 | 1.70E-06 | 4.13 | 0.67 | Increase proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis. Inhibits differentiation [64] |

| EYA4 | 7.37 | 5.43 | 1.45E-07 | 3.83 | 0.70 | Involved in DNA repair [65] |

| LHX1 | 6.41 | 4.48 | 6.96E-05 | 3.81 | 0.64 | Increased proliferation [66] |

| TUBB2B | 5.66 | 3.81 | 2.45E-06 | 3.6 | 0.66 | Essential for microtubule function. Assists in resistance to microtubule targeting agents [67], [30] |

| IGLON5 | 6.20 | 4.42 | 2.66E-07 | 3.44 | 0.68 | Adhesion molecule in neuronal cells. Associated with radiation resistance [68] |

| MAGEA9B | 2.61 | 0.83 | 1.07E-06 | 3.43 | 0.64 | Involved in autophagy pathway and associated with cancer testis antigen [69] |

| CNTFR | 6.98 | 5.22 | 5.48E-06 | 3.4 | 0.67 | Promotes tumor growth [70] |

| DPYSL5 | 3.83 | 2.32 | 1.10E-04 | 2.84 | 0.62 | Axon guidance and targeted by proteins affecting immune function [71] |

| PTH2R | 7.02 | 5.53 | 4.99E-04 | 2.81 | 0.64 | Possible association with MAP kinase pathway [72] |

| IGF2BP1 | 4.86 | 3.39 | 2.30E-05 | 2.76 | 0.65 | Increase cell proliferation and invasion. Promotes resistance to platinum [73,74] |

| SEMA3D | 5.99 | 4.54 | 1.08E-06 | 2.74 | 0.68 | Angiogenesis and metastasis [75] |

| LIN28B | 3.68 | 2.24 | 1.83E-04 | 2.71 | 0.62 | Associated with resistance to platinum, paclitaxel, and radiation [76] |

| NKAIN4 | 4.47 | 3.10 | 1.27E-04 | 2.58 | 0.64 | Associated with gemcitabine resistance [77] |

| FAM84A | 8.17 | 6.81 | 1.74E-08 | 2.56 | 0.70 | DNA Repair [78] |

| ALDH1A2 | 6.76 | 5.42 | 5.90E-05 | 2.54 | 0.65 | Promote cell growth and survival [79] |

| MAL | 9.95 | 8.61 | 3.89E-05 | 2.53 | 0.67 | Associated with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer [80] |

| MFAP4 | 9.63 | 8.30 | 1.11E-06 | 2.51 | 0.69 | Associated with platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. Affects extracellular matrix organization [81] |

|

| ||||||

| Under Expressed Genes | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Gene | High Risk Mean Expression | Low Risk Mean Expression | * p-value | *Fold Change | AUC | Function |

|

| ||||||

| HTR3A | 6.83 | 8.53 | 1.3E-06 | 0.31 | 0.67 | Known to increase immune cell function (both innate and adaptive) [82] |

| PIGR | 5.03 | 6.49 | 9.67E-04 | 0.36 | 0.63 | Leukocyte activation, adaptive immunity [83] |

| IDO1 | 7.19 | 8.59 | 3.38E-06 | 0.38 | 0.68 | Negatively regulates lymphocyte and proliferation [20] |

| CXCL13 | 4.80 | 6.20 | 3.39E-05 | 0.38 | 0.66 | Regulate T cell chemotaxis, cell killing, adaptive immune response [20] |

| DAPL1 | 8.28 | 9.44 | 4.60E-04 | 0.45 | 0.64 | Associated with programmed cell death [20] |

| GJB1 | 8.26 | 9.43 | 3.04E-06 | 0.45 | 0.69 | Under expression associated with impaired recognition by immune cells [84] |

| TNIP3 | 2.38 | 3.50 | 1.38E-06 | 0.46 | 0.68 | Positive regulation of immune response [20] |

| CXCL9 | 7.60 | 8.82 | 3.44E-04 | 0.43 | 0.64 | Positive regulation leukocyte migration, T cell chemotaxis, cell killing [20] |

| CXCL10 | 9.04 | 10.19 | 1.15E-05 | 0.45 | 0.69 | Positive regulation leukocyte migration, T cell chemotaxis, cell killing [20] |

| SLAMF7 | 6.11 | 7.30 | 2.48E-06 | 0.44 | 0.68 | Natural killer cell mediate cytotoxicity, lymphocyte activation [20] |

| PLA2G2D | 3.23 | 4.43 | 1.43E-04 | 0.43 | 0.63 | Lymphocyte proliferation and activation [20] |

| BCL2L15 | 4.40 | 5.51 | 5.87E-06 | 0.46 | 0.66 | Programmed cell death [20] |

| LRG1 | 7.39 | 8.39 | 1.24E-04 | 0.50 | 0.65 | Natural killer cell mediate cytotoxicity, programmed cell death, cell killing [20] |

| GZMB | 4.56 | 5.63 | 4.85E-05 | 0.48 | 0.66 | Natural killer cell mediate cytotoxicity, programmed cell death, cell killing [20] |

| CD38 | 5.05 | 6.15 | 7.47E-07 | 0.47 | 0.69 | Leukocyte activation [20] |

| MMP12 | 3.96 | 5.09 | 1.31E-03 | 0.46 | 0.62 | Positive and negative regulation of immune processes [20] |

| CXCL17 | 7.84 | 8.87 | 8.72E-03 | 0.49 | 0.59 | Leukocyte migration [20] |

| RARRES3 | 9.50 | 10.54 | 6.70E-07 | 0.49 | 0.69 | Regulate cell proliferation [20] |

| LTF | 5.90 | 7.02 | 1.15E-03 | 0.46 | 0.63 | Cell killing, leukocyte activation [20] |

| UBD | 6.80 | 7.96 | 2.81E-04 | 0.45 | 0.63 | Response to interferon-gamma, dendritic cell activation [20] |

| HOXD1 | 7.47 | 8.48 | 2.75E-03 | 0.50 | 0.61 | Differentiation and limb development [20] |

| IL21R | 4.62 | 5.70 | 8.57E-05 | 0.47 | 0.64 | Lymphocyte activation [20] |

| PDZK1IP1 | 8.98 | 9.99 | 3.55E-04 | 0.50 | 0.63 | Transports neoantigens to the cell surface [85] |

| TAP1 | 10.71 | 11.71 | 2.42E-10 | 0.50 | 0.74 | Adaptive immune response [20] |

| IRF4 | 4.23 | 5.25 | 3.09E-04 | 0.49 | 0.63 | Dendritic cell activation, lymphocyte activation, response to interferon gamma [20] |

| SLAMF1 | 2.88 | 3.88 | 4.00E-06 | 0.50 | 0.67 | Adaptive immune response, dendritic cell activation [20] |

p-value represents the level of significance for mean gene expression level compared between the low and intermediate/high risk groups;

Because mean expression is log2 expression, fold change was calculated as 2^(high risk expression - low risk expression).

Discussion

Ovarian cancer remains the deadliest gynecologic malignancy in the United States [1]. There have been multiple new targeted treatments for ovarian cancer, including immunotherapy, anti-angiogenic agents, and PARP inhibitors; however, immunotherapy has not been proven to prolong survival, anti-angiogenic agents only increase progression free survival by 3-4 months, and PARP inhibitors are only minimally effective in patients without BRCA mutations [86-88]. In line with the inability of other agents to sufficiently prolong survival, the PFI remains one of the most important prognostic factors [5,6]. Despite the known importance of PFI and research on platinum resistance, there is still no defined molecular signature for platinum resistance and no known agent which can overcome or reverse it [5,6].

One reason for the difficulty in defining platinum resistance maybe that no single gene dramatically affects prognosis in ovarian cancer. Our data showed that out of over 14,000 genes, only 4 genes had an individual HR of 2 or higher when considered as a continuous variable. Thus, individual genes alone have little impact on actual survival, and thus not predictive of platinum resistance. Despite the modest individual HRs of our 38 genes when using quartile data, the combination of genes together in the consensus Ridge regression model resulted in excellent survival prediction with an HR of 7.63. Furthermore, the low risk patients had an 88% complete response rate to primary therapy compared to only 60% in high/moderate risk patients, demonstrating that transcriptomic signatures are better indicators of treatment response than any individual genes.

Given platinum resistance is such an important prognostic factor for ovarian cancer, any prognostic marker may be associated with treatment response. However, this is not always the case as reported in a previous ovarian cancer study [8], which developed a prognostic gene signature that had no significant association with response rate. On review of 9 ovarian cancer genetic risk scores covered in a recent meta-analysis, unfortunately only one reported an association with response to primary therapy [7-14,89-91]. Because our score was associated with patient response to platinum-based chemotherapy, it may have better clinical utility compared to other risk scores.

The 38 genes in our signature have a variety of functions ranging from autophagy to immune activation. The most dysregulated pathways identified by STRING analysis were related to endocytosis and intracellular transport, both of which have been implicated in platinum resistance [92,93]. Greater than 20% of genes were involved in either of these pathways. Of these genes, UBB has been shown to be consistently under expressed in ovarian and other gynecologic cancers [94,95]. In line with this finding, our data indicated patients who had overexpression of UBB had an improved prognosis. Prior studies have implicated KIAA1033, TRIM27, AGFG1, CCDC53, and XBP1 in platinum resistance [96]. Furthermore, of currently FDA approved drugs, hydroxychloroquine, an antimalarial drug which impacts intracellular transport and autophagy, has been shown to prolong survival in pancreatic cancer [97]. There are currently no trials investigating the role of hydroxychloroquine in combination with platinum and taxane agents in ovarian cancer, but there has been an isolated report that hydroxychloroquine was associated with improved survival [98].

Another highly relevant function, which was not highlighted by STRING analysis, was innate and adaptive immune responses. At least 12 of the 20 genes with a negative RRS were potentially involved in these immune processes. Interferon signaling (EIF4E3, TRIM27), lymphocyte activation (XBP1, BTLA, LCK, and SOCS2), and antigen presentation (UBE2J1, CLEC6A, MON1A, GMPPB) were the most prominent pathways (Table 2). Interestingly, BTLA has been considered to have suppressive immune function and to be upregulated in ovarian cancer cells, which appears counterintuitive to its upregulation among low risk patients [99,100]. However, BTLA has been shown to provide a survival signal to effector T cells [25]. XBP1 and SOCS2 both regulate HLA class II expression, while XBP1 also regulates T cell function and B cell maturation [101-103]. XBP1 has been shown to negatively regulate T cell function in ovarian cancer [104], which is not consistent with its association between higher expression and better survival observed in this study. Furthermore, differential expression analysis of genes with at least a 2-fold higher expression in low risk patients identified that all 26 genes had significant roles in the adaptive immune system (Table 4).

The 38-gene prognostic signature has two components, one component consisted of genes with mostly positive HRs, positive Ridge regression scores and having functions intrinsic to the tumor such as proliferation, apoptosis, and chemoresistance. The second component consisted of genes with mostly an HR < 1, negative Ridge regression scores and having functions largely extrinsic to the tumor in the way of immune function. Each of these two components was prognostic but the best prognostic power came from the combination of both components (Figure 3). The tumor intrinsic signature (Figure 3C) probably accounted for the response to primary therapy, while the tumor-extrinsic signature (Figure 3B) may have explained why the 38-gene signature was also able to differentiate survival within patients who had a complete response to primary therapy. Those low risk patients may have had a more robust innate and adaptive immune response and were likely more capable of eliminating the remaining microscopic tumors by their immune system, resulting in long term survival.

Despite these findings, there are a number of limitations that should be addressed in future studies. These limitations include a holdout dataset for complete independent validation, inclusion of progression free survival information, and application of the score to patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Nevertheless, there were also a number of strengths of to this study. The first of which was the design of an innovative analytic pipeline to discover, optimize and validate prognostic signatures for HGSOC. Furthermore, the created gene signature had two unique components, tumor intrinsic and extrinsic, both of which consisted of a large number of genes that have not been previously explored in ovarian cancer. These genes may be exploited in the future to overcome platinum resistance, increase the duration of response to platinum, and extend patient survival.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Jin-Xiong She’s personal research funds.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, Gaudet MM, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:284–296. doi: 10.3322/caac.21456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A, Berek JS, Chen LM, Cristea M, DeRosa M, ElNaggar AC, Gershenson DM, Gray HJ, Hakam A, Jain A, Johnston C, Leath CA III, Liu J, Mahdi H, Matei D, McHale M, McLean K, O’Malley DM, Penson RT, Percac-Lima S, Ratner E, Remmenga SW, Sabbatini P, Werner TL, Zsiros E, Burns JL, Engh AM. NCCN guidelines insights: ovarian cancer, version 1.2019: featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:896–909. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus CS, Maxwell GL, Darcy KM, Hamilton CA, McGuire WP. Current approaches and challenges in managing and monitoring treatment response in ovarian cancer. J Cancer. 2014;5:25–30. doi: 10.7150/jca.7810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis A, Tinker AV, Friedlander M. “Platinum resistant” ovarian cancer: what is it, who to treat and how to measure benefit? Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133:624–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke SL, Brenton JD. Evolution of platinum resistance in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1169–1174. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waldron L, Haibe-Kains B, Culhane AC, Riester M, Ding J, Wang XV, Ahmadifar M, Tyekucheva S, Bernau C, Risch T, Ganzfried BF, Huttenhower C, Birrer M, Parmigiani G. Comparative meta-analysis of prognostic gene signatures for late-stage ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju049. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Konstantinopoulos PA, Spentzos D, Karlan BY, Taniguchi T, Fountzilas E, Francoeur N, Levine DA, Cannistra SA. Gene expression profile of BRCAness that correlates with responsiveness to chemotherapy and with outcome in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:3555–3561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.5719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. 2011;474:609–615. doi: 10.1038/nature10166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonome T, Levine DA, Shih J, Randonovich M, Pise-Masison CA, Bogomolniy F, Ozbun L, Brady J, Barrett JC, Boyd J, Birrer MJ. A gene signature predicting for survival in suboptimally debulked patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5478–5486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crijns AP, Fehrmann RS, de Jong S, Gerbens F, Meersma GJ, Klip HG, Hollema H, Hofstra RM, te Meerman GJ, de Vries EG, van der Zee AG. Survival-related profile, pathways, and transcription factors in ovarian cancer. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bentink S, Haibe-Kains B, Risch T, Fan JB, Hirsch MS, Holton K, Rubio R, April C, Chen J, Wickham-Garcia E, Liu J, Culhane A, Drapkin R, Quackenbush J, Matulonis UA. Angiogenic mRNA and microRNA gene expression signature predicts a novel subtype of serous ovarian cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kernagis DN, Hall AH, Datto MB. Genes with bimodal expression are robust diagnostic targets that define distinct subtypes of epithelial ovarian cancer with different overall survival. J Mol Diagn. 2012;14:214–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tothill RW, Tinker AV, George J, Brown R, Fox SB, Lade S, Johnson DS, Trivett MK, Etemadmoghadam D, Locandro B, Traficante N, Fereday S, Hung JA, Chiew YE, Haviv I Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. Gertig D, DeFazio A, Bowtell DD. Novel molecular subtypes of serous and endometrioid ovarian cancer linked to clinical outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5198–5208. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman M, Craft B, Brooks A, Zhu J, Haussler D. The UCSC Xena Platform for cancer genomics data visualization and interpretation. bioRxiv. 2018:326470. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 1.1.383). Computer software] Retrieved from https://www.rproject.org 2016.

- 17.Therneau T. A Package for survival analysis in R. R package version 3.1-11. 2020. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival.

- 18.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Glmnet: lasso and elastic-net regularized generalized linear models. R Package Version. 2009:1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Belinky F, Nativ N, Stelzer G, Zimmerman S, Iny Stein T, Safran M, Lancet D. PathCards: multi-source consolidation of human biological pathways. Database (Oxford) 2015;2015:bav006. doi: 10.1093/database/bav006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, Jensen LJ, Mering CV. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burr ML, Cano F, Svobodova S, Boyle LH, Boname JM, Lehner PJ. HRD1 and UBE2J1 target misfolded MHC class I heavy chains for endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2034–2039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016229108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apostolopoulos V, Thalhammer T, Tzakos AG, Stojanovska L. Targeting antigens to dendritic cell receptors for vaccine development. J Drug Deliv. 2013;2013:869718. doi: 10.1155/2013/869718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter RW, Thompson C, Reid DM, Wong SY, Tough DF. Induction of CD8+ T cell responses through trgeting of antigen to Dectin-2. Cell immunol. 2006;239:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haymaker C, Wu RC, Bernatchez C, Radvanyi LG. PD-1 and BTLA and CD8+ T-cell “exhaustion” in cancer: “exercising” an alternative viewpoint. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:735–738. doi: 10.4161/onci.20823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ritthipichai K, Haymaker CL, Martinez M, Aschenbrenner A, Yi X, Zhang M, Kale C, Vence LM, Roszik J, Hailemichael Y, Overwijk WW, Varadarajan N, Nurieva R, Radvanyi LG, Hwu P, Bernatchez C. Multifaceted role of BTLA in the control of CD8(+) T-cell fate after antigen encounter. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6151–6164. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pramanik J, Chen X, Kar G, Henriksson J, Gomes T, Park J-E, Natarajan K, Meyer KB, Miao Z, McKenzie AN. Genome-wide analyses reveal the IRE1a-XBP1 pathway promotes T helper cell differentiation by resolving secretory stress and accelerating proliferation. Genome Med. 2018;10:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0589-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong H, Adams NM, Xu Y, Cao J, Allan DS, Carlyle JR, Chen X, Sun JC, Glimcher LH. The IRE1 endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor activates natural killer cell immunity in part by regulating c-Myc. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:865–878. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0388-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaman MMU, Nomura T, Takagi T, Okamura T, Jin W, Shinagawa T, Tanaka Y, Ishii S. Ubiquitination-deubiquitination by the TRIM27-USP7 complex regulates tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:4971–4984. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00465-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jefferies C, Wynne C, Higgs R. Antiviral TRIMs: friend or foe in autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease? Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:617–625. doi: 10.1038/nri3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stelzer G, Rosen N, Plaschkes I, Zimmerman S, Twik M, Fishilevich S, Stein TI, Nudel R, Lieder I, Mazor Y. The GeneCards suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analyses. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016;54:1.30.1–1.30.33. doi: 10.1002/cpbi.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consortium U. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D506–D515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egwuagu CE, Yu CR, Zhang M, Mahdi RM, Kim SJ, Gery I. Suppressors of cytokine signaling proteins are differentially expressed in Th1 and Th2 cells: implications for Th cell lineage commitment and maintenance. J Immunol. 2002;168:3181–3187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudd PM, Elliott T, Cresswell P, Wilson IA, Dwek RA. Glycosylation and the immune system. Science. 2001;291:2370–2376. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5512.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He R, Huang N, Bao Y, Zhou H, Teng J, Chen J. LRRC45 is a centrosome linker component required for centrosome cohesion. Cell Rep. 2013;4:1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dai P, Liu X, Li QW. Function of the Lck and Fyn in T cell development. Yi Chuan. 2012;34:289–295. doi: 10.3724/sp.j.1005.2012.00289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu P, Tian Y, Chen G, Wang B, Gui L, Xi L, Ma X, Fang Y, Zhu T, Wang D. Ubiquitin B: an essential mediator of trichostatin A-induced tumor-selective killing in human cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:109–118. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inoko A, Yano T, Miyamoto T, Matsuura S, Kiyono T, Goshima N, Inagaki M, Hayashi Y. Albatross/FBF1 contributes to both centriole duplication and centrosome separation. Genes Cells. 2018;23:1023–1042. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James MA, Wen W, Wang Y, Byers LA, Heymach JV, Coombes KR, Girard L, Minna J, You M. Functional characterization of CLPTM1L as a lung cancer risk candidate gene in the 5p15.33 locus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fournier G, Cabaud O, Josselin E, Chaix A, Adelaide J, Isnardon D, Restouin A, Castellano R, Dubreuil P, Chaffanet M. Loss of AF6/afadin, a marker of poor outcome in breast cancer, induces cell migration, invasiveness and tumor growth. Oncogene. 2011;30:3862–3874. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bourdon JC, Renzing J, Robertson P, Fernandes K, Lane D. Scotin, a novel p53-inducible proapoptotic protein located in the ER and the nuclear membrane. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:235–246. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ooi JH, Chen J, Cantorna MT. Vitamin D regulation of immune function in the gut: why do T cells have vitamin D receptors? Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33:77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheng JB, Levine MA, Bell NH, Mangelsdorf DJ, Russell DW. Genetic evidence that the human CYP2R1 enzyme is a key vitamin D 25-hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7711–7715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402490101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sánchez-Pulido L, Rojas AM, Van Wely KH, Martinez-A C, Valencia A. SPOC: a widely distributed domain associated with cancer, apoptosis and transcription. BMC Bio. 2004;5:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapasi K, Inman RD. ME1 epitope of HLA-B27 confers class I-mediated modulation of gram-negative bacterial invasion. J Immunol. 1994;153:833–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toniolo PA, Liu S, Yeh JE, Ye DQ, Barbuto JA, Frank DA. Deregulation of SOCS5 suppresses dendritic cell function in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:46301–46314. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang YW, Cheng HL, Ding YR, Chou LH, Chow NH. EMP1, EMP 2, and EMP3 as novel therapeutic targets in human cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2017;1868:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang R, Xing L, Zheng X, Sun Y, Wang X, Chen J. The circRNA circAGFG1 acts as a sponge of miR-195-5p to promote triple-negative breast cancer progression through regulating CCNE1 expression. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0933-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 48.Wu F, Zhou J. CircAGFG1 promotes cervical cancer progression via miR-370-3p/RAF1 signaling. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6269-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patch AM, Christie EL, Etemadmoghadam D, Garsed DW, George J, Fereday S, Nones K, Cowin P, Alsop K, Bailey PJ. Whole-genome characterization of chemoresistant ovarian cancer. Nature. 2015;521:489–494. doi: 10.1038/nature14410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, Wang J, Wang A, Yu J. CA9 is an important molecular marker for the prognosis of osteosarcoma patients. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi Y, Qi W, Liu S, Sun L, Ding A, Yu G, Li H, Wang Y, Qiu W, Lv J. TSPAN9 suppresses the chemosensitivity of gastric cancer to 5-fluorouracil by promoting autophagy. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-1089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chao LC, Zhang Z, Pei L, Saito T, Tontonoz P, Pilch PF. Nur77 coordinately regulates expression of genes linked to glucose metabolism in skeletal muscle. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2152–2163. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartlett BJ, Isakson P, Lewerenz J, Sanchez H, Kotzebue RW, Cumming RC, Harris GL, Nezis IP, Schubert DR, Simonsen A. p62, Ref (2) P and ubiquitinated proteins are conserved markers of neuronal aging, aggregate formation and progressive autophagic defects. Autophagy. 2011;7:572–583. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.6.14943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terashima M, Fujita Y, Togashi Y, Sakai K, De Velasco MA, Tomida S, Nishio K. KIAA1199 interacts with glycogen phosphorylase kinase β-subunit (PHKB) to promote glycogen breakdown and cancer cell survival. Oncotarget. 2014;5:7040–50. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kashkin KN, Musatkina EA, Komelkov AV, Sakharov DA, Trushkin EV, Tonevitsky EA, Vinogradova TV, Kopantzev EP, Zinovyeva MV, Kovaleva OV, Arkhipova KA, Zborovskaya IB, Tonevitsky AG, Sverdlov ED. Genes potentially associated with resistance of lung cancer cells to paclitaxel. Dokl Biochem Biophys. 2011;437:105–8. doi: 10.1134/S1607672911020153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brunckhorst MK, Xu Y, Lu R, Yu Q. Angiopoietins promote ovarian cancer progression by establishing a procancer microenvironment. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:2285–2296. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen JJ, Zhang W. High expression of WWP1 predicts poor prognosis and associates with tumor progression in human colorectal cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2018;8:256–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D’Arcangelo D, Giampietri C, Muscio M, Scatozza F, Facchiano F, Facchiano A. WIPI1, BAG1, and PEX3 autophagy-related genes are relevant melanoma markers. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:1471682. doi: 10.1155/2018/1471682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vicent S, Luis-Ravelo D, Antón I, García-Tuñón I, Borrás-Cuesta F, Dotor J, De Las Rivas J, Lecanda F. A novel lung cancer signature mediates metastatic bone colonization by a dual mechanism. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2275–2285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chalhoub N, Baker SJ. PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:127–150. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu C, Zhang H, Liu C, Wang C. Upregulation of lncRNA CALML3-AS1 promotes cell proliferation and metastasis in cervical cancer via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:5611–5620. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201907_18295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Livingstone C. IGF2 and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20:R321–R339. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brouwer-Visser J, Huang GS. IGF2 signaling and regulation in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2015;26:371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Z, Jiang S, Lu C, Ji T, Yang W, Li T, Lv J, Hu W, Yang Y, Jin Z. SOX11: friend or foe in tumor prevention and carcinogenesis? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919853449. doi: 10.1177/1758835919853449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakamoto D, Takagi T, Fujita M, Omura S, Yoshida Y, Iida T, Yoshimura S. Basic gene expression characteristics of glioma stem cells and human glioblastoma. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:597–607. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ghiaghi M, Forouzesh F, Rahimi H. Effect of sodium butyrate on LHX1 mRNA expression as a transcription factor of HDAC8 in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2019;11:317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu X, Zhang Y, Wu B, Kurie JM, Pertsemlidis A. The miR-195 axis regulates chemoresistance through TUBB and lung cancer progression through BIRC5. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2019;14:288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.omto.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Perez-Añorve IX, Gonzalez-De la Rosa CH, Soto-Reyes E, Beltran-Anaya FO, Del Moral-Hernandez O, Salgado-Albarran M, Angeles-Zaragoza O, Gonzalez-Barrios JA, Landero-Huerta DA, Chavez-Saldaña M. New insights into radioresistance in breast cancer identify a dual function of miR-122 as a tumor suppressor and oncomiR. Mol Oncol. 2019;13:1249–1267. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weon JL, Potts PR. The MAGE protein family and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;37:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vicent S, Sayles LC, Vaka D, Khatri P, Gevaert O, Chen R, Zheng Y, Gillespie AK, Clarke N, Xu Y. Cross-species functional analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts identifies a critical role for Clcf1 and Il-6 in non-small cell lung cancer in vivo. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5744–5756. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liston A, Papadopoulou AS, Danso-Abeam D, Dooley J. MicroRNA-29 in the adaptive immune system: setting the threshold. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69:3533–3541. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1124-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin P, Guo YN, Shi L, Li XJ, Yang H, He Y, Li Q, Dang YW, Wei KL, Chen G. Development of a prognostic index based on an immunogenomic landscape analysis of papillary thyroid cancer. Aging. 2019;11:480–500. doi: 10.18632/aging.101754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang X, Zhang H, Guo X, Zhu Z, Cai H, Kong X. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding protein 1 (IGF2BP1) in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:88. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Blagden S, Abdel Mouti M, Chettle J. Ancient and modern: hints of a core post-transcriptional network driving chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018;9:e1432. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Neufeld G, Mumblat Y, Smolkin T, Toledano S, Nir-Zvi I, Ziv K, Kessler O. The role of the semaphorins in cancer. Cell Adh Migr. 2016;10:652–674. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2016.1197478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Balzeau J, Menezes MR, Cao S, Hagan JP. The LIN28/let-7 pathway in cancer. Front Genet. 2017;8:31. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2017.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhou M, Ye Z, Gu Y, Tian B, Wu B, Li J. Genomic analysis of drug resistant pancreatic cancer cell line by combining long non-coding RNA and mRNA expression profling. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:38–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pebernard S, Perry JJP, Tainer JA, Boddy MN. Nse1 RING-like domain supports functions of the Smc5-Smc6 holocomplex in genome stability. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4099–4109. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tomita H, Tanaka K, Tanaka T, Hara A. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in stem cells and cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:11018–32. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee PS, Teaberry VS, Bland AE, Huang Z, Whitaker RS, Baba T, Fujii S, Secord AA, Berchuck A, Murphy SK. Elevated MAL expression is accompanied by promoter hypomethylation and platinum resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. International J Cancer. 2010;126:1378–1389. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao H, Sun Q, Li L, Zhou J, Zhang C, Hu T, Zhou X, Zhang L, Wang B, Li B, Zhu T, Li H. High expression levels of AGGF1 and MFAP4 predict primary platinum-based Chemoresistance and are associated with adverse prognosis in patients with serous ovarian Cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10:397–407. doi: 10.7150/jca.28127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shajib MS, Khan WI. The role of serotonin and its receptors in activation of immune responses and inflammation. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2015;213:561–574. doi: 10.1111/apha.12430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Turula H, Wobus CE. The role of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor and secretory immunoglobulins during mucosal infection and immunity. Viruses. 2018;10:237. doi: 10.3390/v10050237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kleopa KA. The role of gap junctions in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Neurosc. 2011;31:17753–17760. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4824-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.García-Heredia JM, Carnero A. The cargo protein MAP17 (PDZK1IP1) regulates the immune microenvironment. Oncotarget. 2017;8:98580–98597. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.21651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ledermann JA, Colombo N, Oza AM, Fujiwara K, Birrer MJ, Randall LM, Poddubskaya EV, Scambia G, Shparyk YV, Lim MC, Bhoola SM, Sohn J, Yonemori K, Stewart RA, Zhang X, Zohren F, CLinn C, Monk BJ. Avelumab in combination with and/or following chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone in patients with previously untreated epithelial ovarian cancer: results from the phase 3 javelin ovarian 100 trial. Gynecologic Oncology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00342-9. Presented at SGO Annual Meeting 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rossi L, Verrico M, Zaccarelli E, Papa A, Colonna M, Strudel M, Vici P, Bianco V, Tomao F. Bevacizumab in ovarian cancer: a critical review of phase III studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:12389–12405. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Swisher EM, Kaufmann SH, Birrer MJ, et al. Exploring the relationship between homologous recombination score and progression-free survival in BRCA wildtype ovarian carcinoma: analysis of veliparib plus carboplatin/paclitaxel in the velia study. SGO. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kang J, D’Andrea AD, Kozono D. A DNA repair pathway-focused score for prediction of outcomes in ovarian cancer treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:670–681. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yoshihara K, Tajima A, Yahata T, Kodama S, Fujiwara H, Suzuki M, Onishi Y, Hatae M, Sueyoshi K, Fujiwara H, Kudo Y, Kotera K, Masuzaki H, Tashiro H, Katabuchi H, Inoue I, Tanaka K. Gene expression profile for predicting survival in advanced-stage serous ovarian cancer across two independent datasets. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yoshihara K, Tsunoda T, Shigemizu D, Fujiwara H, Hatae M, Fujiwara H, Masuzaki H, Katabuchi H, Kawakami Y, Okamoto A, Nogawa T, Matsumura N, Udagawa Y, Saito T, Itamochi H, Takano M, Miyagi E, Sudo T, Ushijima K, Iwase H, Seki H, Terao Y, Enomoto T, Mikami M, Akazawa K, Tsuda H, Moriya T, Tajima A, Inoue I, Tanaka K. High-risk ovarian cancer based on 126-gene expression signature is uniquely characterized by downregulation of antigen presentation pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1374–1385. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liang XJ, Mukherjee S, Shen DW, Maxfield FR, Gottesman MM. Endocytic recycling compartments altered in cisplatin-resistant cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2346–2353. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stewart DJ. Mechanisms of resistance to cisplatin and carboplatin. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63:12–31. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Haakonsen DL, Rape M. Ubiquitin levels: the next target against gynecological cancers? J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4228–4230. doi: 10.1172/JCI98262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kedves AT, Gleim S, Liang X, Bonal DM, Sigoillot F, Harbinski F, Sanghavi S, Benander C, George E, Gokhale PC, Nguyen QD, Kirschmeier PT, Distel RJ, Jenkins J, Goldberg MS, Forrester WC. Recurrent ubiquitin B silencing in gynecological cancers establishes dependence on ubiquitin C. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:4554–4568. doi: 10.1172/JCI92914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lloyd KL, Cree IA, Savage RS. Prediction of resistance to chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:117. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zeh H, Bahary N, Boone BA, Singhi AD, Miller-Ocuin JL, Normolle DP, Zureikat AH, Hogg ME, Bartlett DL, Lee KK, Tsung A, Marsh JW, Murthy P, Tang D, Seiser N, Amaravadi RK, Espina V, Liotta L, Lotze MT. A randomized phase II preoperative study of autophagy inhibition with high-dose hydroxychloroquine and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer patients. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;97:106144. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cadena I, Werth VP, Levine P, Yang A, Downey A, Curtin J, Muggia F. Lasting pathologic complete response to chemotherapy for ovarian cancer after receiving antimalarials for dermatomyositis. Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:837. doi: 10.3332/ecancer.2018.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Imai Y, Hasegawa K, Matsushita H, Fujieda N, Sato S, Miyagi E, Kakimi K, Fujiwara K. Expression of multiple immune checkpoint molecules on T cells in malignant ascites from epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2018;15:6457–6468. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.8101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang T, Ye L, Han L, He Q, Zhu J. Knockdown of HVEM, a lymphocyte regulator gene, in ovarian cancer cells increases sensitivity to activated T cells. Oncol Res. 2016;24:189–196. doi: 10.3727/096504016X14641336229602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liou HC, Boothby MR, Finn PW, Davidon R, Nabavi N, Zeleznik-Le NJ, Ting J, Glimcher LH. A new member of the leucine zipper class of proteins that binds to the HLA DR alpha promoter. Science. 1990;247:1581–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.2321018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tomer S, Chawla YK, Duseja A, Arora SK. Dominating expression of negative regulatory factors downmodulates major histocompatibility complex Class-II expression on dendritic cells in chronic hepatitis C infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5173–5182. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i22.5173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Todd DJ, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Kowal C, Lee AH, Volpe BT, Diamond B, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Glimcher LH. XBP1 governs late events in plasma cell differentiation and is not required for antigen-specific memory B cell development. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2151–2159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Song M, Sandoval TA, Chae CS, Chopra S, Tan C, Rutkowski MR, Raundhal M, Chaurio RA, Payne KK, Konrad C, Bettigole SE, Shin HR, Crowley MJP, Cerliani JP, Kossenkov AV, Motorykin I, Zhang S, Manfredi G, Zamarin D, Holcomb K, Rodriguez PC, Rabinovich GA, Conejo-Garcia JR, Glimcher LH, Cubillos-Ruiz JR. IRE1alpha-XBP1 controls T cell function in ovarian cancer by regulating mitochondrial activity. Nature. 2018;562:423–428. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0597-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.