Abstract

Shewanella spp. possess a broad respiratory versatility, which contributes to the occupation of hypoxic and anoxic environmental or host-associated niches. Here, we observe a strain-specific induction of biofilm formation in response to supplementation with the anaerobic electron acceptors dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and nitrate in a panel of Shewanella algae isolates. The respiration-driven biofilm response is not observed in DMSO and nitrate reductase deletion mutants of the type strain S. algae CECT 5071, and can be restored upon complementation with the corresponding reductase operon(s) but not by an operon containing a catalytically inactive nitrate reductase. The distinct transcriptional changes, proportional to the effect of these compounds on biofilm formation, include cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) turnover genes. In support, ectopic expression of the c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase YhjH of Salmonella Typhimurium but not its catalytically inactive variant decreased biofilm formation. The respiration-dependent biofilm response of S. algae may permit differential colonization of environmental or host niches.

Subject terms: Biofilms, Environmental microbiology

Introduction

A hallmark of members of the genus Shewanella is their remarkable respiratory versatility since they can respire on an array of organic and inorganic compounds comprising virtually any electron acceptor more electronegative than sulfate1,2. The respiratory capacity of Shewanella is reinforced by mediator-directed electron transfer mechanisms enabling the efficient reduction of insoluble substrates such as metal oxides3. This respiratory flexibility results in an extraordinary physiological versatility that contributes to the environmental abundance of the chemoorganotroph shewanellae as versatile colonizers of oxic, hypoxic, and anoxic marine and freshwater habitats2. Some species, primarily Shewanella algae and close relatives such as Shewanella chilikensis, have been associated with human disease4,5.

Biofilm formation promotes the colonization of biotic and abiotic substrata in Shewanella spp. and many other bacterial species6. This predominantly sedentary lifestyle is a developmental process initiated by an attachment of single cells that subsequently form microcolonies prior to the establishment of mature biofilms. The intracellular second messenger cyclic diguanylate monophosphate (c-di-GMP) is known to play a key role in the lifestyle switch from planktonic to sessile and vice versa in a plethora of Gram-negative species7,8. Integration of extra- and intracellular stimuli modulates different features of this multicellular microbial lifestyle in response to changes in nutrient availability, temperature, oxygen tension, quorum sensing, and various chemical signals9,10. For example, reduced oxygen tension differentially regulates biofilm formation in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 and Shewanella putrefaciens CN3211,12. For Shewanella spp., life within a biofilm provides structural and functional advantages, spanning from maintenance of redox balance to enhanced extracellular electron transfer13–15. Shewanella spp. thrive in hypoxic and anoxic environments including sediments, hypoxic water bodies, and the intestinal tract of fish and invertebrates16–18, where these non-fermentative species use some of the most abundant inorganic and organic alternative electron acceptors (AEAs). While biofilm formation on insoluble metal oxides has been well documented19, knowledge on the behavioral and physiological biofilm responses upon use of the broad array of AEAs is limited in Shewanella species, as is the repertoire of terminal reductases enabling the respiration of AEAs.

Here we show that supplementation of a seawater-mimicking medium with organic or inorganic AEAs induces differential, strain-specific biofilm formation in S. algae. Assessment of the respiratory capacity of the strains combined with mutant analyses of the type strain S. algae CECT 5071 demonstrated that respiration is required, but not sufficient per se to increase biofilm production upon AEA supplementation. Transcriptome analyses showed that the number of differentially regulated genes positively correlated with the amount of biofilm formed by S. algae CECT 5071 upon addition of the electron acceptors DMSO and nitrate. Several of the differentially regulated genes encoded proteins that participate in c-di-GMP turnover. Altogether, our study suggests that differential biofilm formation in S. algae strains is governed beyond respiration by the induction of distinct biofilm developmental programs.

Results

Alternative electron acceptors promote strain-specific biofilm formation in S. algae

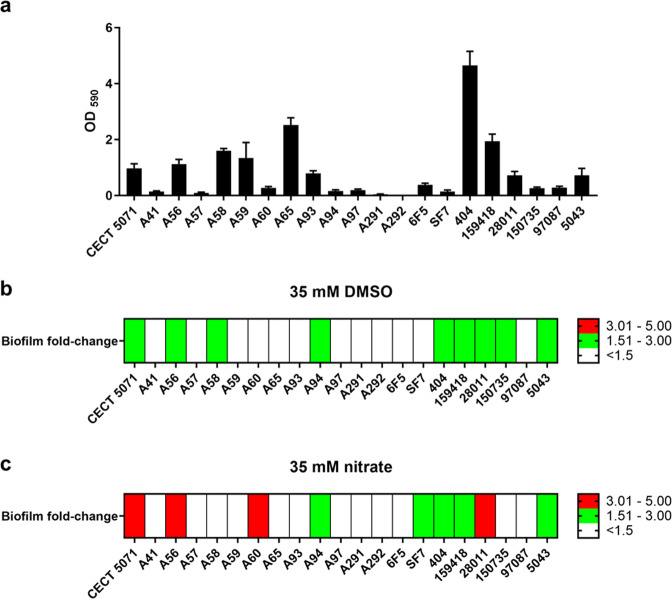

While screening chemical libraries for biofilm inhibitors, we noticed that an addition of 35 mM DMSO enhanced biofilm formation of S. algae CECT 5071 static cultures ~2-fold compared to the non-supplemented control. Since a similar phenomenon had not been observed with other DMSO-respiring bacteria, we reasoned that this phenotype could be specific to S. algae. We therefore analyzed DMSO-mediated biofilm formation in a selection of 20 S. algae strains from various environmental and clinical sources (Supplementary Table 1). Biofilm formation in plain Marine Broth (MB) varied substantially between isolates, from poor biofilm formers to proficient biofilm producers (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1). Biofilm formation values in MB were taken as baseline levels for comparisons upon AEA supplementation. Thus, for 9 of the 20 strains we observed a more than 1.5-fold induction of biofilm formation in response to DMSO (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Biofilm formation response of S. algae strains in the absence or presence of supplemented alternative electron acceptors.

a Biofilm formation for 21 S. algae strains in MB medium in the absence of added electron acceptors. b Heatmap representing the fold-change in biofilm formation with respect to the corresponding non-supplemented control upon addition of 35 mM DMSO. c Heatmap representing the fold-change in biofilm formation with respect to the corresponding non-supplemented control upon addition of 35 mM sodium nitrate. Data represent the average of two biological replicates with six technical replicates each.

Since the respiratory repertoire of Shewanella spp. is broad, we wondered whether other AEAs provoked a similar strain-specific biofilm response. To that end, we analyzed the biofilm response of the type strain S. algae CECT 5071 and the other 20 S. algae isolates towards 35 mM nitrate, another representative AEA during anaerobic respiration (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3). With an increase of more than 4-fold, S. algae CECT 5071 showed the most pronounced increase in biofilm formation as determined by CV staining. Further 9 strains, 2 of which are different to those reported above for DMSO, responded with increased biofilm formation to nitrate supplementation.

To ensure that the observed biofilm induction was not due to pH changes upon utilization of the different AEAs, experiments were validated by testing the type strain S. algae CECT 5071 in the absence or presence of AEAs in MB buffered by 30 mM HEPES pH = 7.5, which minimized pH oscillations during 24-h static incubation (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The corresponding results were similar to those recorded in unbuffered medium (Supplementary Fig. 4b) showing that AEA-induced changes in biofilm formation are not caused by pH changes. Taken together, these results indicate that DMSO and nitrate-induced biofilm formation is a strain-specific phenotype independent of pH.

DMSO respiration is not conserved in S. algae

We hypothesized that respiration of the supplemented compounds triggered the biofilm formation response. However, we wondered whether the respiratory activity differed for strains that responded with enhanced biofilm formation. To answer this question, we qualitatively assessed nitrate reductase activity in S. algae strains by measuring the accumulation of nitrite in static cultures supplemented with 35 mM nitrate. A straightforward colorimetric assay with endpoint determination of nitrate reductase activity in live bacteria20 showed similar overall nitrate reductase activity in all strains (Fig. 2a). This indicates that the biofilm formation response is not related to an intrinsic capacity of a given strain to reduce the supplemented AEA.

Fig. 2. Nitrate and DMSO reduction capacity of S. algae strains.

a Biofilm induction is not related to the ability of the strains to utilize the supplemented compound, as indicated by a qualitative nitrate reduction test performed for all 21 strains, showing nitrite production as indicated by the formation of a pink complex. Uninoculated MB medium supplemented with 35 mM nitrate was used as blank. b Evolutionary history of DmsA orthologs inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Whelan and Goldman model. Bootstrap support values are indicated in the nodes of the phylogenetic reconstruction.

The genomes of these and other S. algae strains have been sequenced as part of ongoing comparative genomics studies (Martín-Rodríguez et al., unpublished). In S. algae, nitrate reduction occurs in the periplasm and relies in a duo-NAP system, comprised of NAP-α (encoded by the napEDABC operon) and NAP-β (encoded by the napDAGHB operon), being NapA-α and NapA-β the major catalytic subunits, respectively. To investigate genomic determinants for the observed biofilm phenotypes, BLASTp searches were conducted to identify CECT 5071 NapA-α and NapA-β orthologs in the S. algae strains used. Both components of the NAP system were present in all S. algae genomes analyzed, with amino acid sequence identities between 97.1–99.9% for NapA-α and 98.1–99-1% for NapA-β with respect to the corresponding protein in the type strain (data not shown), thus indicating that the two nitrate reductases are conserved across S. algae isolates.

The terminal DMSO reductase DmsEFABGH is involved in extracellular DMSO respiration and uses several sulfoxides and N-oxides as substrates21,22, with DmsA being the major catalytic subunit. We next performed BLASTp searches of S. algae CECT 5071 DmsA orthologs to identify the presence of DMSO reductases in our sequenced S. algae genomes. We could retrieve hits for all S. algae strains except for A41, A57, and 97087. Genes predicted to encode the dmsEFABGH operon are located between accB and rpmE on the S. algae CECT 5071 chromosome. Inspection of the WGS of strains S. algae A41, S. algae A57, and S. algae 97087 revealed absence of this operon (data not shown). Besides, DmsA orthologs with a significantly lower sequence identity were found in S. algae A56 and S. algae CCUG 58400 (not used in this study, originally described as Shewanella upenei23 but demonstrated to be a later heterotypic synonym of S. algae24) that shared only modest sequence identity (55.8% both) with the reference protein. Interestingly, their sequence was almost identical to the DmsA homolog of S. chilikensis (GenBank accession: WP_165565699.1). A maximum-likelihood reconstruction of the evolutionary relationships of S. algae DmsA in relation with other Shewanella spp. DmsA orthologs is presented in Fig. 2b. DmsA orthologs from S. algae A56 and S. algae CCUG 58400 are within a well-supported separate clade, that is only distantly related to the housekeeping S. algae DmsA. Altogether, these findings suggest DMSO respiration is a variable, potentially adaptive feature in S. algae, with evidence of selective loss or acquisition from other Shewanella spp.

Surface-associated electron acceptors enhance S. algae substrate colonization

Since S. algae encounters diverse AEAs in its native ecosystems, we hypothesized that biofilm formation could be a selective response promoting bacterial colonization of distinct substrata that are abundant in AEAs, a process that could lead to differential ecological niche occupation by distinct isolates. To test this hypothesis, we selected DMSO and nitrate as two representative AEAs and two S. algae strains, the DMSO and nitrate responder S. algae CECT 5071 and the non-responder S. algae A291. To mimic an environmentally relevant situation, the AEAs were incorporated into an agarose pad (Fig. 3a), and biofilm formation of each strain was examined using non-supplemented agarose as a control. The release of immobilized AEAs from the solid agarose pad could be visualized using the colored cobalt (II) nitrate as illustrated in Fig. 3b. S. algae CECT 5071 exhibited substantially increased biofilm formation on the agarose surface upon incorporation of DMSO or nitrate (Fig. 3c), as observed with supplemented medium. Consistently, while a monolayer of cells was observed in non-supplemented agarose, elaborated biofilm structures were observed primarily in the presence of nitrate and to a lesser degree with DMSO. Conversely, non-responsive S. algae A291 showed a similar low biofilm formation compared to the non-supplemented agarose pad irrespective of whether DMSO or nitrate had been added to the agarose (Fig. 3c). Thus, induction of biofilm formation is preserved upon incorporation of soluble AEAs into an agarose pad and their gradual release from a surface. This experimental set-up mimics environmentally relevant situations S. algae may find, for example, when bacteria encounter decaying organic matter in the aquatic milieu or on the surface of organisms such as fish or algae.

Fig. 3. Electron acceptors promote strain-specific biofilm formation of S. algae.

a Experimental set-up to assess biofilm formation by S. algae. Alternative electron acceptors (AEAs) were incorporated into ultra-pure agarose, from which they are progressively released. b Visualization of AEA release from agarose. Shown is a recipient with agarose containing cobalt (II) nitrate that is overlaid with water. c Surface colonization patterns of S. algae CECT 5071 and S. algae A291 on agarose plugs containing either no AEAs or 35 mM of the selected AEAs DMSO or sodium nitrate visualized by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy after staining with the BacLight viability kit. Representative images are shown.

Respiration and biofilm formation are intimately related in S. algae

To investigate the physiological basis of AEA-induced biofilm formation in S. algae CECT 5071, we next questioned whether respiration of the supplemented AEA is required for biofilm formation. To provide experimental evidence of an association between biofilm formation and reduction of AEAs, we first deleted the dmsB gene encoding the DMSO reductase subunit B of the DmsEFABGH reductase (Fig. 4a). To assess DMSO reduction by the WT strain and its ΔdmsB mutant derivative, we quantified the generation of dimethylsulfide (DMS), the product of DMSO respiration, in static cultures supplemented with 35 mM DMSO. Deletion of dmsB impaired the capacity to reduce DMSO by >75% (Fig. 4b) as determined by GC-MS.

Fig. 4. Disruption of terminal reductase activity abrogates the biofilm response.

a Schematic of the DMSO reductase encoding dmsEFABGH operon of Shewanella algae. b DMSO reduction of the WT strain and dmsB in-frame deletion mutant (****P < 0.0001, two-tailed unpaired t test) as evidenced by measuring DMS production of three independent cultures supplemented with 35 mM DMSO. c Biofilm formation of S. algae CECT 5071 WT and ∆dmsB in the absence or presence of DMSO (****P < 0.0001, two-tailed unpaired t test). Data represent the average and SD of three biological replicates with seven technical replicates each. d Schematic of the periplasmic nitrate reductase NAP-α encoding operon napEDABC and NAP-β encoding operon napDAGHB of S. algae. e Nitrate reduction by the single mutants ∆napABC (α−) and ∆napA (β−), and the double mutant ∆napABC ∆napA (αβ−) as determined by nitrite accumulation with respect to the WT strain upon supplementation with 35 mM nitrate (****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test; ND no nitrite production detected). Data represent the average and SD of three biological replicates with four technical replicates per sample. f Biofilm formation of S. algae CECT 5071 WT and nitrate reduction mutants in the absence or presence of sodium nitrate (****P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post-hoc test).

We next studied biofilm formation in static cultures of the WT and mutant strain in MB in the absence or presence of 35 mM DMSO. In the absence of DMSO, both the WT strain and its ΔdmsB mutant exhibited similar biofilm formation and growth patterns; the latter characterized by preferential growth as a pellicle at the air–liquid interface (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 5a). In the presence of DMSO, WT growth was stimulated as compared to the non-supplemented control and occurred at the air–liquid interface as well as in the lower layers of the well. In contrast, growth of the ∆dmsB mutant in the presence of DMSO was similar to that in non-supplemented MB (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Biofilm formation in the WT was increased ~2-fold with respect to non-supplemented cultures as previously observed (Fig. 4c), an increase caused by higher biofilm formation on the bottom of the well (Supplementary Fig. 5a), whereas the ΔdmsB mutant generated a similar amount of biofilm compared to the control without DMSO (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that DMSO respiration is required for the increase in relative biofilm formation upon supplementation with DMSO.

In S. algae CECT 5071 supplementation of MB with nitrate caused a more pronounced increase in biofilm formation than supplementation with DMSO (Fig. 3c). To extend the hypothesis of respiration-driven biofilm formation in S. algae, we deleted the nitrate reductase subunits A-C (napABC) from NAP-α, and the nitrate reductase subunit A (napA) from NAP-β (Fig. 4d) in the CECT 5071 genetic background that resulted in the single in-frame deletion mutants ΔnapABC (hereafter referred to as α−) and ΔnapA (hereafter referred to as β−), and the double deletion mutant ΔnapABC ΔnapA (hereafter referred to as αβ−). To assess the capacity of the WT versus the mutant strains to respire nitrate, we measured the production of nitrite, the product of nitrate reduction, in static cultures supplemented with 35 mM nitrate. Deletion of NAP-α genes reduced nitrite accumulation by almost 80%, whereas deletion of NAP-β genes did not significantly affect nitrate reduction in comparison to the WT (Fig. 4e). Thus, the catalytic activity of NAP-α represents the major fraction of the nitrate reduction capacity compared to NAP-β under the assay conditions used for S. algae CECT 5071. Deletion of napABC and napA rendered S. algae unable to produce nitrite upon addition of nitrate (Fig. 4e).

We next analyzed biofilm formation of the mutants in static cultures with and without 35 mM nitrate. In the absence of nitrate, the WT and all mutants formed a similar amount of biofilm (Fig. 4f), and the patterns of growth and biofilm formation on the walls and bottom of the wells were also similar (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In the presence of nitrate, growth in the anoxic layers of the wells was observed for the WT and mutants lacking a functional NAP-α or NAP-β, but not in the nitrate reduction null mutant αβ− (Supplementary Fig. 5b). While biofilm formation in the β− mutant was not significantly different from that of the WT strain, the α− mutant formed significantly more biofilm than the WT (Fig. 4f), an increase that was due to higher biofilm formation on the bottom of the well as visually determined by CV staining (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In contrast, the double mutant αβ−, unable to reduce nitrate, did not respond to nitrate supplementation with increased biofilm formation with respect to non-supplemented cultures (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 5b). This indicates that, in analogy to DMSO, nitrate respiration drives biofilm formation in S. algae CECT 5071, and suggests that each nitrate reductase plays a distinct role on biofilm formation upon nitrate addition.

Reductase activity is required to elicit biofilm formation

So far, our genetic analyses demonstrate that respiration of AEAs can selectively act as driver for biofilm formation. In WT S. algae CECT 5071, AEA-induced biofilm formation is dose-dependent, as shown by dose-response measurements up to a DMSO or nitrate concentration of 70 mM (Supplementary Fig. 6). These experiments also showed that the onset of AEA mediated stimulation of biofilm formation was at ~4 mM for nitrate and 8 mM for DMSO. The ΔdmsB mutant did not respond with enhanced biofilm formation upon addition of DMSO. In contrast, single mutants of nitrate reductases NAP-α (ΔnapABC) and NAP-β (ΔnapA) showed a dose-dependent response. As expected, the αβ− mutant did not respond to nitrate.

To demonstrate that the mutant phenotypes were specific for the deletion of reductase subunits and not a consequence of secondary mutations, we complemented the ∆dmsB mutant with the dmsEFABGH operon cloned under the lac promoter in the pSRK-Km vector. In the complemented ΔdmsB mutant, DMS production was duplicated with respect to WT levels (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 7), compatible with overexpression of the reductase upon β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction. The introduction of the empty pSRK-Km plasmid in the WT or ΔdmsB strains did not significantly change DMS production with respect to the corresponding parental strains (data not shown). Introduction of the empty vector pSRK-Km per se increased biofilm formation, leading to a higher baseline level of biofilm formation (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 8) that masked the effect of DMSO addition. While no significant differences were observed between biofilm levels of the WT and ∆dmsB harboring the empty plasmid, the complemented mutant though showed increased biofilm formation (Fig. 5b). This could also be qualitatively assessed visually as the WT and ∆dmsB pSRK-Km::dmsEFABGH strains tended to form more biofilm on the bottom of the wells in the presence of DMSO, although the effect of the electron acceptor was negligible compared to the high level of biofilm formation at the air–liquid interface caused by plasmid introduction (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5. Ectopic expression of terminal reductases restores catalytic activity and biofilm formation.

a Restoration of DMSO reductase activity as determined by DMS production in the ∆dmsB mutant upon overexpression of the dmsEFAGHB operon (average ± SD, n = 3) in comparison to the WT and ∆dmsB strains harboring the empty expression plasmid pSRK-Km (****P < 0.0001; one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test). b Biofilm formation of the complemented ∆dmsB mutant and the corresponding WT and ∆dmsB empty pSRK-Km vector controls. Data represent the average and SD of three biological replicates with seven technical replicates per sample. Statistical significance of the differences was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (***P < 0.001, ns not significant). c Biofilm formation patterns on the walls and bottom of the wells of S. algae WT pSRK-Km, S. algae ∆dmsB pSRK-Km, and complemented S. algae ∆dmsB pSRK-Km-dmsEFABGH as visually assessed by CV staining. Note that biofilm formation differences on the bottom of the wells by the WT harboring the empty plasmid pSRK-Km and complemented mutant with respect to the ∆dmsB mutant harboring the empty expression vector are not apparent from the quantitative determinations shown on b because of the vector effect. d Nitrate reductase activity in complemented α−, β−, and αβ− mutants as determined by nitrite production, as well as in a catalytic napEDABC mutant in which three of the four cysteines of the 4Fe-4S cluster of NapA had been replaced by serine. Data represent the average and SD of three biological replicates with four technical replicates per sample. Statistical significance of the differences was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ND no nitrite production detected). e Biofilm formation of complemented nitrate reduction mutants and the corresponding WT and nitrate reduction null strains harboring the empty pSRK-Km plasmid, and the catalytic mutant. Data represent the average and SD of three biological replicates with seven technical replicates each. Statistical significance of the differences was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test.

To complement the nitrate reductase mutants α−, β−, and αβ−, individual napEDABC and napDAGHB operons and both operons in tandem were cloned under the lac promoter into the pSRK-Km vector. Nitrate reductase activity was partially restored to ~40% by ectopic expression of napEDABC in the α− mutant with low levels of nitrate reductase (Fig. 5d). Nitrate reductase activity of the β− mutant, which presented a nitrate reduction capacity similar to the WT, was significantly increased upon expression of napDAGHB. Complementation of the αβ− strain with napDAGHB only marginally restored nitrate reductase activity, whereas expression of napEDABC, or both napDAGHB and napEDABC, restored nitrate reductase activity to ~40 and 60% of the WT levels, respectively. As the induction of biofilm formation caused by nitrate is higher than that caused by DMSO, the effect of nitrate supplementation was not abrogated by plasmid introduction. Thus, complemented α− and β− mutants showed similar biofilm formation phenotypes than the WT strain upon nitrate supplementation (Fig. 5e). Partial complementation of the WT biofilm phenotype upon nitrate addition was recorded for the αβ− pSRKKm-NAP-β strain, whereas levels comparable to the WT were recorded for the αβ− pSRKKm-NAP-α and αβ− pSRKKm-NAP-α-NAP-β strains (Fig. 5e). Altogether, these data indicate that restoration of reductase activity restores the biofilm formation response in the presence of the electron acceptors.

To demonstrate the specificity of our results, we engineered a napEDABC operon containing a catalytically inactive NAP-α reductase by replacing three of the four cysteines, Cys48, Cys51, and Cys55 responsible for coordination of the 4Fe-4S cluster of NapA, with serine. Overexpression of the resulting mutant NAP-α* in the pSRK-Km plasmid in the αβ− background did not restore nitrite production (Fig. 5d), and biofilm formation remained at the αβ− mutant levels upon supplementation with nitrate (Fig. 5e). This demonstrates that the reductase activity, and not the mere expression of the reductase per se in the periplasm, triggers the biofilm formation response.

Global transcriptional changes induced by alternative electron acceptors

To gain a deeper understanding of the physiological responses induced by different AEAs, transcriptional profiles were obtained from S. algae CECT 5071 grown in static culture in the absence or presence of 35 mM DMSO or nitrate (Supplementary Data 1). Statistically significant changes in transcript levels (P-adj ≤ 0.05) of a total of 3553 genes were noted in S. algae CECT 5071 exposed to DMSO or nitrate (Fig. 6a). There was a tendency between the number of transcripts changed in the presence of a given AEA and the corresponding effect on biofilm formation, since more genes had altered transcript levels in the presence of nitrate as compared to DMSO. Thus, there were 1573 genes with altered transcript levels in the presence of DMSO (Fig. 6b–d; 798 upregulated and 775 downregulated) and 3254 in the presence of nitrate (Fig. 6b, c, e; 1594 upregulated and 1660 downregulated). There was a substantial overlap in the transcriptional response to both AEAs, with 1323 genes having altered transcript levels (either upregulated or downregulated) in either condition (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6. Transcriptomic profiles of S. algae CECT 5071 static cultures supplemented with DMSO or nitrate.

Venn diagrams of (a) differentially expressed genes (P-adj < 0.05) in both treatments, (b) genes with upregulated transcript levels and (c) genes with downregulated transcript levels. Volcano plots showing alterations in gene transcript levels in static cultures supplemented with 35 mM DMSO (d) and nitrate (e). In red are the genes that are significantly differentially regulated (P-adj < 0.05) with a fold-change value below 2 or above 0.5. In orange are the rest of differentially expressed genes. Black indicates genes not significantly differentially regulated. COG assignation of differentially expressed genes in S. algae CECT 5071 upon addition of 35 mM DMSO (f) or sodium nitrate (g) versus control cultures without electron acceptor addition. COG categories: [A] RNA processing and modification; [B] Chromatin structure and dynamics; [C] Energy production and conversion; [D] Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning; [E] Amino acid transport and metabolism; [F] Nucleotide transport and metabolism; [G] Carbohydrate transport and metabolism; [H] Coenzyme transport and metabolism; [I] Lipid transport and metabolism; [J] Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis; [K] Transcription; [L] Replication, recombination and repair; [M] Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis; [N] Cell motility; [O] Post-translational modification, protein turnover, and chaperones; [P] Inorganic ion transport and metabolism; [Q] Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport, and catabolism; [R] General function prediction only; [S] Function unknown; [T] Signal transduction mechanisms; [U] Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport; [V] Defense mechanisms; [W] Extracellular structures; [Y] Nuclear structure; and [Z] Cytoskeleton.

Next, genes were classified according to functionality in clusters of orthologous genes (COGs). In the DMSO response, the highest number of upregulated and downregulated transcripts (132 genes, 65 upregulated, and 67 downregulated) belonged to the COG category signal transduction mechanisms [T] (Fig. 6f). This was also the case for nitrate, that modulated transcript levels of 273 genes belonging to this category (136 upregulated and 137 downregulated, Fig. 6g). These data suggest that respiration of AEAs involves downstream intracellular signaling events resulting in increased biofilm formation, consistent with the transcriptional landscape described above. An enrichment analysis using PANTHER25 showed a significant enrichment (P < 0.05) for the ‘sulfate assimilation’ and ‘de novo purine biosynthesis’ categories for both treatments, although the high number of transcripts showing altered expression levels in the presence of DMSO and nitrate suggest that both electron acceptors elicit global physiological changes. We also classified upregulated and downregulated transcripts for each condition into gene ontology (GO) categories. GO terms of the categories “biological processes” and “molecular function” are presented for DMSO (Supplementary Fig. 9a, b) and nitrate (Supplementary Fig. 9c, d). In both treatments, the most populated GO terms under “biological processes” were metabolic processes (GO:0008152) and cellular processes (GO:0009987), irrespective of the directionality of the expression change, indicative of a major physiological reprogramming imposed by AEA supplementation. Likewise, “catalytic activity” (GO:0003824) was the most represented GO term of the “molecular function” category for both DMSO and nitrate supplementation, which is also consistent with the notion that both compounds induce a physiological re-adaptation.

A putative role of c-di-GMP signaling

As noted above, signal transduction mechanisms were highly affected by DMSO or nitrate supplementation. A hallmark of the genus Shewanella is the abundance of proteins that catalyze the synthesis or breakdown of c-di-GMP, suggesting a central role of c-di-GMP-mediated signaling in Shewanella biology. We identified 63 putative c-di-GMP turnover proteins in the genome of S. algae CECT 5071 as part of ongoing genomic studies (Martín-Rodríguez et al., in preparation). In the absence of specific gene nomenclature, we refer to the genes encoding these proteins with provisional generic names, but the corresponding GenBank locus tags are given in parentheses to unambiguously identify the genes. To investigate their transcriptional changes induced by DMSO or nitrate supplementation, we plotted the transcriptome of the 63 genes encoding putative diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and c-di-GMP phosphodiesterases (PDEs) containing GGDEF/EAL/HD-GYP domains in a heatmap (Fig. 7a). This analysis revealed discrete changes caused by DMSO addition, with gene WT_00831 (E1N14_04100) encoding a PAS-GGDEF domain containing protein being the most differentially upregulated by 2.4-fold with respect to the control without electron acceptor supplementation. Nitrate supplementation caused more extensive changes in the c-di-GMP turnover transcriptome, with the putative DGCs WT_00655 (E1N14_03230) and WT_00831 (E1N14_04100) being the most differentially upregulated by 8.5- and 6.8-fold, respectively, with respect to control cultures. Another gene encoding a GGDEF-domain protein, WT_00826 (E1N14_04075) was the most downregulated, 0.14-fold, with respect to the control. Altogether, these data support the notion of an involvement of c-di-GMP signaling in respiration-mediated regulation of biofilm formation in S. algae CECT 5071.

Fig. 7. Putative role of c-di-GMP signaling on AEA-induced biofilm formation.

a Heatmap showing transcriptional changes (log2 fold-change) of genes encoding putative c-di-GMP turnover proteins upon DMSO or nitrate supplementation. b Biofilm formation of S. algae CECT 5071 WT harboring the empty plasmid pBBR1MCS-2 (denoted as VC for “vector control”) or expressing the PDE from S. Typhimurium YhjH or the catalytically inactive derivative YhjH E136A cloned in this plasmid in the absence or in the presence of 35 mM DMSO or nitrate. Data represent the average and SD of three biological replicates with seven technical replicates per sample. Statistical significance of the differences was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test (****P < 0.0001, ns not significant).

We reasoned that if c-di-GMP signaling mediates AEA-dependent biofilm formation, a decrease of intracellular c-di-GMP pools would revert the phenotype upon AEA supplementation. To artificially alter c-di-GMP levels, the heterologous c-di-GMP PDE YhjH from S. Typhimurium and the catalytically inactive derivative YhjH E136A were cloned into plasmid pBBR1MCS-2, introduced in S. algae CECT 5071, and the biofilm phenotypes of YhjH and YhjH E136A expressing strains were compared with respect to that of the control strain harboring the empty vector in plain MB and MB supplemented with 35 mM DMSO or nitrate (Fig. 7b). Expression of YhjH significantly decreased biofilm formation in MB, whereas biofilm formation of the strain expressing YhjH E136A was not significantly different than that of the vector control. In the presence of DMSO there were no statistically significant differences between the vector control and the YhjH or YhjH E136A expressing strains, although a trend towards lower biofilm formation was noted in the strain expressing the active PDE. In the presence of nitrate, YhjH expressing cells formed significantly lower biofilm than the vector control whereas cells expressing YhjH E136A formed statistically significantly higher biofilm. Taken together, these results suggest that a decrease of intracellular [c-di-GMP] decreases biofilm formation in static culture and counteracts to some extent the effect of AEA supplementation.

Finally, to validate RNA-seq results and to test the reproducibility of our data, RNA was isolated from static S. algae CECT 5071 cultures as performed for transcriptomic analysis, and the expression of six relevant genes was tested by qRT-PCR and compared to transcript levels obtained by RNA-seq: dmsB (E1N14_09855); napA-α (E1N14_17675); napA-β (E1N14_03175); WT_00826 (E1N14_04075); WT_00831 (E1N14_04100); and WT_00655 (E1N14_03230) (Supplementary Fig. 10). The differential expression of these genes was similar in the transcriptomic and qRT-PCR analyses, which validates the RNA-seq data.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate a specific differential induction of biofilm formation in response to respiration in S. algae. We show that the presence and subsequent utilization of soluble electron acceptors in a seawater-mimicking growth medium induces biofilm formation in some but not all S. algae strains tested. Disruption of the corresponding respiratory pathway as well as mutant complementation with a catalytically inactive variant abolished the capacity of DMSO or nitrate to stimulate biofilm formation.

In S. algae, biofilm formation is strain-specifically upregulated upon supplementation with various electron acceptors. Thereby, respiration and biofilm formation are directly coupled as mutants in the respective terminal reductase did not respond with altered biofilm formation. A physiological link between cellular respiration and regulation of biofilm formation has been observed in other bacteria. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, nitrate respiration has been found to contribute to biofilm formation and development under static growth26, while in Burkholderia pseudomallei, nitrate respiration was found to inhibit biofilm formation by decreasing global c-di-GMP cellular pools27. Anaerobic respiration has been reported to induce biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae and Staphylococcus epidermidis, thereby promoting host colonization28,29. In Staphylococcus aureus, biofilm formation is promoted under anoxic conditions in response to the oxidation state of the membrane quinone pool30. Opposite roles for oxygen have been reported for other Shewanella spp. where low oxygen promoted c-di-GMP-mediated biofilm formation in S. putrefaciens CN3211 or induced biofilm detachment in S. oneidensis MR-112. Altogether, these findings suggest the existence of an extensive, but variable interplay between biofilm formation and the nature of the electron acceptor in respiration.

In our study we used two representative electron acceptors, nitrate and DMSO. Our results implicate that the two periplasmic nitrate reductases of S. algae play different, non-redundant roles under nitrate-rich conditions. Thus, a mutant lacking a functional NAP-β does not show alterations in biofilm formation and global nitrate reductase activity in comparison to the WT as determined by nitrite assessment in culture supernatants, but a mutant lacking a functional NAP-α exhibits a strong impairment in nitrate reduction capacity and altered biofilm formation patterns. The greater contribution of NAP-α to nitrate reduction under static growth conditions is also reflected by a higher expression of this reductase than the other isoform, NAP-β. The nitrate reductase is a complex multidomain protein consisting of the core subunits NapA and NapB, the chaperone NapD and variable accessory subunits31. NapA is the catalytic subunit containing a [4Fe-4S] cluster, whereas NapB shuttles electrons from the membrane electron transport protein CymA to NapA. Replacement of NapA-α Cys48, Cys51, and Cys55 involved in the coordination of the [4Fe-4S] cluster32 with serine was shown to prevent nitrate reduction and we show that a nitrate reduction-null mutant expressing such a catalytically deficient NapA-α is unable to induce biofilm formation upon nitrate supplementation. To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to functionally analyze nitrate reductase activity (and their contribution to biofilm formation) in a Shewanella species harboring both NAP isoforms, as is the case for most shewanellaceae as shown by whole-genome sequencing31, thus establishing a functional link between respiration and biofilm formation, two prima facie independent processes.

Like nitrate, DMSO also elicited strain-specific biofilm formation. Remarkably, genome sequence analysis of S. algae strains showed the DMSO reductase DmsEFABGH not to be conserved across the sequenced isolates, and in some cases, not present at all. In some S. algae isolates, high sequence identity of the catalytic subunit DmsA with orthologs from other Shewanella spp. was noted and demonstrated by phylogenetic analysis. The diversity of gene clusters encoding DMSO reductases in different Shewanella species has been shown22. However, the intra-species variability of the DMSO reductase operon indicates that DMSO respiration is under strong evolutionary pressure in S. algae. Loss or lateral acquisition of respiratory features by S. algae from other Shewanella spp. points to currently unexplored ecological and physiological advantages.

The ability to reduce a given electron acceptor was not necessarily associated with increased biofilm formation. As illustrated for nitrate, while all S. algae isolates reduced nitrate to nitrite, not all of them responded with enhanced biofilm formation indicating that AEA sensing with subsequent upregulation of biofilm formation can be functionally uncoupled from AEA respiration. Sensory domains in signal transduction systems have been reported to detect nitrate and directly couple it to enhanced biofilm formation through increased levels of c-di-GMP, a ubiquitous biofilm activator. For example, in P. aeruginosa, nitrate sensing by the GGDEF-EAL domain containing protein MucR via its MHYT domain induces expression of the exopolysaccharide alginate33. Another study showed that homologs of the nitrate-sensing two-component system NarX/NarL in B. pseudomallei is involved in the regulation of biofilm formation by potentially interfering with c-di-GMP levels27. Furthermore, accumulation close to insoluble electron acceptors has been observed to require chemotaxis and electron transport chain components34,35.

The habitat of S. algae includes coastal and oceanic sediments as well as the water column2, where microbial reduction of inorganic and organic soluble and insoluble electron acceptors are a central part of the Earth’s global biogeochemical cycles22,36,37. DMSO is a relatively abundant compound in seawater thought to play a key role in the global sulfur cycle38. Most of DMSO is produced from DMS, a climate active gas responsible for the main exchange of sulfur between the oceans and the atmosphere. DMS is the main end product of the degradation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP), an algal osmolyte synthetized by phytoplankton39 at an estimated rate of 109 tons per year in the oceans40,41. As an adaptive trait, two differentially expressed dms operons are found in Shewanella piezotolerans WP318. Local pools of AEAs are also available in certain host body niches colonized by Shewanella spp. including the intestinal tract17. Niche partitioning with the emergence of specific ecotypes that have lost the ability to respire on certain AEAs such as DMSO, TMAO, or thiosulfate has evolved in S. baltica. This type of genomic evolution is thought to have led to the existence of carbon source and redox-specialized S. baltica communities in sediments of the Baltic Sea42,43. In S. algae, niche partitioning, at least in the case of nitrate, is more complex since it combines enhanced biofilm formation with the ability to respire the AEA. Both biofilm and non-biofilm responsive strains have been found to perform dissimilatory reduction of nitrate as an AEA prototype. While the concentration of DMSO and nitrate used as a reference in this study (35 mM) is higher than that in the natural habitat, i.e. seawater, local mM concentrations of these AEAs may be found in certain niches. For example, DMSO concentrations of 30–90 mM have been reported in the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi44. A study has shown S. oneidensis to perform positive chemotaxis towards senescent E. huxleyi cells45, supporting the notion that Shewanella spp. is attracted by gradients of AEAs permitting their metabolization. The genera of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria Beggiatoa and Thioploca accumulate up to 500 mM nitrate intracellularly as an electron acceptor for sulfide oxidation46. Likewise, high nitrate concentrations could occur at the interface with nitrate-rich fecal or decaying organic material47.

In the natural environment, AEAs are rarely encountered homogeneously, but are present in gradients that can be sensed by microorganisms. Sedimented organic material or phytoplankton are sources of nitrate and DMSO48–50. Solid agarose colonization upon incorporation of the AEAs DMSO and nitrate has given direct evidence that sensing and respiration promote substrate colonization by S. algae. Positive chemotaxis towards soluble and insoluble AEAs has been reported for S. oneidensis MR-1 and S. putrefaciens35,51,52 and may contribute to the elevated biofilm development on abiotic or biotic surfaces containing AEAs53. Shewanella spp. exploit surface attachment and biofilm formation in conjunction with respiration of insoluble AEAs54,55. However, whether surface attachment and biofilm formation play a role in the respiration of highly diffusible AEAs is poorly characterized. Electroactivity measurements revealed increases in Shewanella biofilm formation upon elevation of c-di-GMP levels13, thus enhanced biofilm formation could correlate with improved electrical transfer.

Because of their outstanding metabolic and respiratory flexibility, regulation of gene expression, including terminal reductases, is complex in Shewanella spp. The anaerobic reduction pathways of Shewanella spp. have been shown to be promiscuous, sometimes involving the simultaneous utilization of several electron acceptors56. Oxygen limitation has been shown to elicit swift changes in energy metabolism, cytochrome production, and formation of conductive nanowires in S. oneidensis MR-157. Transcriptomic analyses under defined anaerobic conditions have shown that anaerobic reduction pathways, such as nitrate and Mn(IV) reduction, are deeply intertwined in S. algae58,59. There is an oxygen gradient within biofilms, which adds another layer to the complexity of oxygen-mediated regulatory processes60.

Following the trend observed in biofilm formation experiments, the extension of the global transcriptional changes induced on S. algae CECT 5071 was higher for nitrate than for DMSO, consistent with transcriptomic analyses reported for S. oneidensis MR-1 upon exposure to these electron acceptors61. Conclusively, this observation indicates fundamental metabolic differences, and perhaps biofilm characteristics, between growth conditions to accompany the combined respiration and biofilm-driven niche adaptation. Since signal transduction genes corresponded to the most populated family under both conditions, environmental sensing and regulation are likely to play key roles in conferring the enhanced biofilm phenotype. Among the signal transduction pathways of Shewanella spp. that regulate biofilm formation, c-di-GMP signaling occupies a prevalent position with Shewanella spp. having one of the largest number of c-di-GMP turnover proteins among prokaryotes7. Transcription of the putative DGC with an N-terminal PAS sensory domain WT_00831 (E1N14_04100) was found to be upregulated in the presence of both DMSO and nitrate, thus constituting a primary candidate for future studies aimed at deciphering the underlying molecular mechanism of the biofilm response. Transcript levels of other two DGCs, WT_00826 (E1N14_04075) and WT_00655 (E1N14_03230) were found to be significantly shifted by nitrate. This suggests c-di-GMP, or another second messenger cyclic dinucleotide signaling pathway, as a candidate pathway regulating respiration-mediated biofilm formation in S. algae. This notion is further supported by differential biofilm formation upon expression of the heterologous PDE YhjH and its catalytic mutant YhjH E136A from S. Typhimurium, presumably as a consequence of artificially altered intracellular c-di-GMP pools.

In summary, in this work we have provided evidence that reductase activity is required for AEA-induced biofilm formation in S. algae. Deletion mutants in the different reductases characterized the physiological role of respiration in terms of activity and biofilm induction. Given the complexity of the electron transport systems and signal transduction pathways in S. algae, and the strain-specific nature of this phenomenon, this work provides an entry point for follow-up studies of comparative transcriptomic analyses of responsive and non-responsive S. algae isolates as well as extensive mutational analyses to identify and characterize specific regulatory pathways linking respiration with biofilm formation. Furthermore, we report that biofilm formation is closely interwoven with the use of different electron acceptors by S. algae. We show that the two NAP isoforms of S. algae play substantially different roles on cellular nitrate reduction and nitrate reduction-mediated biofilm formation. We also demonstrate DMSO reduction to be a variable feature in S. algae with evidence of loss or horizontal acquisition in certain isolates. Respiration-driven biofilm formation may therefore constitute a mechanism of niche colonization by specialized S. algae strains, not only in anoxic environments where certain AEAs are abundant, but also in moderately oxygenated environments by taking advantage of their broad respiratory repertoire and reducing thereby the consequences of microbial competition for oxygen. Apart from deciphering the underlying molecular mechanisms, this work provides a sound basis for future research aimed at establishing the phylogenetic spread of the phenomenon studied here.

Methods

Strains and growth conditions

The Shewanella strains used in this study (Supplementary Table 1) were routinely grown in MB or on marine agar (MA) (Difco). Escherichia coli strains (Supplementary Table 1) were routinely grown in Luria broth (LB) or on Luria agar (LA). When necessary, the medium was supplemented with kanamycin (50 µg ml−1), streptomycin (200 µg ml−1), IPTG (0.5 mM), and/or diaminopimelic acid (0.3 mM).

Genetic manipulations

The R6K-origin plasmid pKNG101 was used for allelic replacement in S. algae CECT 5071. For in-frame deletion of the target genes dmsB (minor subunit of the DMSO reductase DmsAB), napABC (periplasmic nitrate reductase NAP-α, subunits A, B, and C) and napA (periplasmic nitrate reductase NAP-β, subunit A), the chromosomal regions immediately up- and down-stream the genes of interest were PCR-amplified and fused in plasmid pKNG101 using the primers and restriction sites indicated in Supplementary Table 2. To create the dmsB deletion, the DNA fragments comprising the 347-bp upstream and 355-bp downstream the dmsB gene were initially cloned into pUC18Not using the restriction sites indicated in Supplementary Table 2, and then subcloned into pKNG101 at the NotI site. The resulting plasmids were propagated in E. coli DH5α λpir, isolated, and electroporated into E. coli MFDpir from which they were mobilized into S. algae CECT 5071 by conjugation. Recombinants generated by single-crossover recombination were selected on LA plates containing Sm. Double crossover was induced upon re-streaking merodiploids on plates containing 10% (w/v) sucrose. In-frame gene deletion mutants were confirmed by PCR using primers flanking the recombination sites (Supplementary Table 2) followed by Sanger sequencing. To complement the mutations, the relevant operons dmsEFABGH, napDAGHB and napEDABC were cloned individually or in tandem under the control of the plac promoter in pSRK-Km using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2. The cloning strains E. coli TOP10 and NEB-5α were used for plasmid propagation. All plasmid constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

The wild-type yhjH gene from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 NalR (UMR1) and the catalytically inactive derivative YhjH E136A were cloned into pBBR1MCS-2 with primers yhjH-F-HindIII and yhjH-R-XbaI (Supplementary Table 2) using S. Typhimurium UMR1 genomic DNA or plasmid pRGS462 as templates, respectively, followed by Sanger DNA sequencing.

Generation of catalytically inactive NapA

To generate a catalytically inactive NapA-α enzyme, three of the four cysteines coordinating the 4Fe-4S cluster in the nitrate reductase α catalytic subunit NapA were replaced by serine (C48S, C51S and C55S). Nucleotide exchanges were introduced with the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) following the manufacturer’s instructions (primers in Supplementary Table 2). The nucleotide replacements were verified by Sanger sequencing.

Biofilm formation assays

In total, 200 µl bacterial cultures were incubated statically in 96-well plates (TPP, #92096) at 30 °C for 24 h in MB in the absence or presence of 35 mM of DMSO or sodium nitrate. Concentration-dependent biofilm formation was assessed in the absence or presence of 0.55-70 mM DMSO and nitrate. Adherent cells were quantified by crystal violet (CV) staining as previously described with minor modifications63. Briefly, after staining adherent cells with a 0.2% (w/v) CV solution, the biofilm-associated dye was dissolved with 30% (v/v) acetic acid. Total biofilm biomass is reported as OD590 absorbance. Biofilm formation patterns including pellicle formation were documented using 96-well strip plates (Greiner Bio-One, #762070).

Phylogenetic analyses

Identification of S. algae CECT 5071 dimethyl sulfoxide reductase DmsA and nitrate reductase NapA orthologs was performed by BLASTp against the whole-genome sequencing contigs of 41 S. algae strains (Martín-Rodríguez et al., unpublished) using the Uppmax computational cluster (National Genomics Infrastructure, Sweden), followed by manual inspection of the corresponding genomic loci. The evolutionary history of terminal reductases DmsA and NapA was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and the Whelan and Goldman model64 after 1000 bootstrap replications as implemented in MEGA X65. The nucleotide sequences of dmsA orthologs are available at the NCBI GenBank (accession numbers: MT953034-MT953072).

Confocal microscopy

To assess biofilm formation on surfaces containing AEAs, 35 mM DMSO and nitrate were added to 2.5 ml 2.5% (w/v) ultrapure agarose (Bio-Rad), which was dispensed in 6-well tissue culture plates and allowed to solidify. Non-supplemented agarose was used as a control surface. Agarose disks were overlaid with 8 ml of bacterial suspensions containing ~1 × 106 CFU ml−1 of S. algae CECT 5071, a strain responding to both AEAs with increased biofilm formation, and S. algae A291, a strain that does not exhibit a AEA-mediated biofilm response, and then incubated statically overnight. The bacterial cultures were then removed by aspiration and the agarose disks washed three times with sterile PBS. Biofilm bacteria were stained using the BacLight viability kit (Invitrogen). Sections of ~0.5 × 0.5 cm were excised with a sterile scalpel for imaging in an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope. Experiments involved two biological replicates with two technical replicates each, and a minimum of three sections were imaged per technical replicate.

Gas chromatography

Determination of DMSO reductase activity in static bacterial cultures in MB supplemented with 35 mM DMSO was performed by quantification of DMS production by GC-MS (Varian 450GC-240MS). In all, 10 ml vials containing 5 ml bacterial cultures adjusted to an initial OD600 of 0.05 in MB medium supplemented with DMSO were sealed and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. Controls included a culture of S. algae CECT 5071 WT in MB not supplemented with DMSO, as well as sterile medium supplemented with 35 mM DMSO. The cultures were pre-conditioned at 30 °C for 2 min under agitation before extraction of 0.1 ml gas using a Head Space syringe and injection at 250 °C in split mode. A DB5-MS UI (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm) column was used with He as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 ml min–1. The GC oven was programmed to rise from 40 °C (3 min) to 220 °C at 100 °C min-1 (1 min). DMS was detected by a mass spectrometer with an EI ion source running in TIC Full Scan mode (scanning m/e 32–300). Experiments involved three biological replicates.

Determination of nitrate reductase activity

Nitrate reductase activity in static cultures of strains grown in MB supplemented with 35 mM nitrate was determined spectrophotometrically by measuring the accumulation of nitrite in supernatants upon addition of 0.02% (w/v) N-(1-napthyl)ethylenediamine in 95% (v/v) ethanol and 1% sulfanilamide (w/v) in 1.5 N HCl as previously described20. Optical readings were taken at OD540 in 96-well plates. Experiments involved at least three biological replicates.

RNA isolation and sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from static overnight cultures of S. algae CECT 5071 in non-supplemented MB or the same medium supplemented with 35 mM DMSO or 35 mM nitrate. Prior to RNA isolation, cultures (three biological replicates per test condition) were homogenized by inverting the tubes to ensure representative sampling of the entire bacterial population. RNA purification was performed with the Direct-Zol RNA Miniprep Plus kit (Zymo Research) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Residual genomic DNA was removed by DNase treatment with the Turbo DNA-free kit (Ambion). DNA contamination was assessed with a 40 cycle PCR using the DNase-treated RNA samples as templates. The RNA quality was examined on a 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent). The relative integrity (RIN) values were 9.6–10.

Prior to sequencing, rRNA was depleted from 550 ng of total RNA using Illumina Ribo-Zero rRNA removal kit for Gram-negative bacteria. Sequencing libraries were then prepared using Illumina TruSeq stranded total RNA kit. The libraries were pooled and 1% of PhiX control library was added to the pool. The pool was sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 machine in High Output run mode using v4 chemistry. The read length was PE125.

Low quality sequence reads and adapters were removed with AfterQC66 using default parameters and the remaining contaminating rRNA was removed with SortMeRNA67. Read counts per gene were obtained using the package Salmon68 with default parameters. To identify differentially expressed genes, the DESeq2 R/Bioconductor package was used69. RNA-seq reads were deposited at the NCBI database (accession number: GSE133627).

The annotation of S. algae CECT 5071 genes was classified into functional families using the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) by BLASTP with 60% minimum alignment coverage, 50 minimum bitscore, and 35% minimum percent identity.

Proteins were classified into families and subfamilies with an ontology term (GO), PANTHER protein class, and PANTHER pathway using its classification system (www.pantherdb.org25). Statistical enrichment analysis for differentially expressed genes was considered as significant when the FDR-adjusted P-value was inferior to 0.05. Analyses were assisted by Python scripts.

qRT-PCR validation of RNA-seq data

Quantitative real time PCR was used to validate differential gene transcript levels using RNA isolated from S. algae CECT 5071 cultures under the same conditions as described above. The primers used in qRT-PCR reactions are listed in Supplementary Table 2. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) using 1 μg of RNA. Quantitative PCR reactions were prepared with the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and run on a LightCycler 480 instrument (Roche) using the pre-defined SYBR Green reaction protocol. Relative gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method70.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Lone Gram (DTU, Denmark), Dr. Margarita Bolaños (Hospital Unversitario Insular de Gran Canaria), and Dr. Fernando Artiles-Campelo (Hospital Dr. Negrín de Gran Canaria) for provision of Shewanella algae strains, and Prof. Didier Mazel (Institut Pasteur, Paris) for the kind gift of E. coli MFDpir. AJM-R acknowledges funding from FEMS (RG2015-0084), the Karolinska Institutet Research Foundation (FS-2018:0007), the Hans Dahlbergs Foundation, the Lars Hiertas Minne Foundation (FO2018-0196), and the Längmanska Kulturfonden (BA19-1128). J.M.G. acknowledges funding from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (CTM2016-80095-C2-2-R). Work at the EEZ was supported by grants to TK from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BIO2013-42297 and BIO2016-76779-P). U.R. was supported by the Swedish Research Council for Natural Sciences and Engineering (project numbers 621-2013-4809 and 2017-04465) and Karolinska Institutet. The GC-MS experiments were conducted by Dr. Rafael Núñez Gómez from the Scientific Instrumentation Service of the Estación Experimental del Zaidín (Granada, Spain). RNA sequencing was performed at the Science for Life Laboratory (SciLife Lab), Uppsala, Sweden. The authors are grateful to Dr. K. Thorell (University of Gothenburg) for bioinformatics support and to Dr. M. A. Matilla (EEZ-CSIC), funded by the Spanish Ministry for Science, Innovation and Universities (PID2019-103972GA-I00), for experimental assistance during the revision of this work.

Author contributions

Study - original idea: A.J.M.-R. Study - design and conceptualization: A.J.M.-R. and U.R. Experiments: A.J.M.-R., assisted by J.A.R.-D. and D.M.-M. Data analysis: A.J.M.-R., J.M.G., T.K., and U.R. Writing - original draft: A.J.M.-R. Writing - review and editing: A.J.M.-R., T.K., and U.R., with the input of all co-authors. All authors read and approved the final version before submission.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Karolinska Institute.

Data availability

RNA sequencing data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank with the accession code GSE133627. The Whole Genome Shotgun project of S. algae CECT 5071 is available at the NCBI GenBank under the accession code SMNR00000000. The nucleotide sequences of dmsA orthologs used for phylogenetic analysis are available at the NCBI GenBank under accession codes MT953034-MT953072.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alberto J. Martín-Rodríguez, Email: jonatan.martin.rodriguez@ki.se

Ute Römling, Email: ute.romling@ki.se.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41522-020-00177-1.

References

- 1.Nealson, K. H. & Scott, J. Ecophysiology of the genus Shewanella. In The Prokaryotes. 1133–1151 (Springer New York, 2006).

- 2.Hau HH, Gralnick JA. Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007;61:237–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotloski NJ, Gralnick JA. Flavin electron shuttles dominate extracellular electron transfer by Shewanella oneidensis. MBio. 2013;4:e00553–12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00553-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martín-Rodríguez AJ, Martín-Pujol O, Artiles-Campelo F, Bolaños-Rivero M, Römling U. Shewanella spp. infections in Gran Canaria, Spain:retrospective analysis of 31 cases and a literature review. JMM Case Rep. 2017;4:e005131. doi: 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martín-Rodríguez AJ, Suárez-Mesa A, Artiles-Campelo F, Römling U, Hernández M. Multilocus sequence typing of Shewanella algae isolates identifies disease-causing Shewanella chilikensis strain 6I4. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019;95:fiy210. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiy210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dang H, Lovell CR. Microbial Surface Colonization and biofilm development in marine environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016;80:91–138. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00037-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Römling U, Galperin MY, Gomelsky M. Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013;77:1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martín-Rodríguez AJ, Römling U. Nucleotide second messenger signaling as a target for the control of bacterial biofilm formation. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017;17:1928–1944. doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170105144424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolter R, Greenberg EP. The superficial life of microbes. Nature. 2006;441:300–302. doi: 10.1038/441300a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toyofuku M, et al. Environmental factors that shape biofilm formation. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2016;80:7–12. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1058701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C, et al. Oxygen promotes biofilm formation of Shewanella putrefaciens CN32 through a diguanylate cyclase and an adhesin. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1945. doi: 10.1038/srep01945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thormann KM, et al. Control of formation and cellular detachment from Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 biofilms by cyclic di-GMP. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:2681–2691. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2681-2691.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu T, et al. Enhanced Shewanella biofilm promotes bioelectricity generation. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2015;112:2051–2059. doi: 10.1002/bit.25624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang Y, Xiang Y, Sun G, Wu W-M, Xu M. Electron acceptor-dependent respiratory and physiological stratifications in biofilms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015;49:196–202. doi: 10.1021/es504546g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y, et al. Extracellular polymeric substances are transient media for microbial extracellular electron transfer. Sci. Adv. 2017;3:e1700623. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caro-Quintero A, et al. Genome sequencing of five Shewanella baltica strains recovered from the oxic-anoxic interface of the Baltic Sea. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1236. doi: 10.1128/JB.06468-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King GM, Judd C, Kuske CR, Smith C. Analysis of stomach and gut microbiomes of the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) from coastal Louisiana, USA. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e51475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong L, Jian H, Zhang Y, Xiao X. The two sets of DMSO respiratory systems of Shewanella piezotolerans WP3 are involved in deep sea environmental adaptation. Front. Microbiol. 2016;7:1418. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell AC, et al. Role of outer membrane c-type cytochromes MtrC and OmcA in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 cell production, accumulation, and detachment during respiration on hematite. Geobiology. 2012;10:355–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-4669.2012.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streeter JG, Devine PJ. Evaluation of nitrate reductase activity in Rhizobium japonicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983;46:521–524. doi: 10.1128/AEM.46.2.521-524.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sambasivarao D, Weiner JH. Differentiation of the multiple S- and N-oxide-reducing activities of Escherichia coli. Curr. Microbiol. 1991;23:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF02092258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gralnick JA, Vali H, Lies DP, Newman DK. Extracellular respiration of dimethyl sulfoxide by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4669–4674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505959103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K-K, et al. Shewanella upenei sp. nov., a lipolytic bacterium isolated from bensasi goatfish Upeneus bensasi. J. Microbiol. 2011;49:381–386. doi: 10.1007/s12275-011-0175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thorell K, Meier-Kolthoff JP, Sjöling Å, Martín-Rodríguez AJ. Whole-genome sequencing redefines Shewanella taxonomy. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1861. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D419–D426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Alst NE, Picardo KF, Iglewski BH, Haidaris CG. Nitrate sensing and metabolism modulate motility, biofilm formation, and virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 2007;75:3780–3790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00201-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mangalea MR, Plumley BA, Borlee BR. Nitrate sensing and metabolism inhibit biofilm formation in the opportunistic pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei by reducing the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:1353. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marrero K, et al. Anaerobic growth promotes synthesis of colonization factors encoded at the Vibrio pathogenicity island in Vibrio cholerae El Tor. Res. Microbiol. 2009;160:48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uribe-Alvarez C, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis: metabolic adaptation and biofilm formation in response to different oxygen concentrations. Pathog. Dis. 2016;74:ftv111. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftv111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mashruwala AA, van de Guchte A, Boyd JM. Impaired respiration elicits SrrAB-dependent programmed cell lysis and biofilm formation in Staphylococcus aureus. Elife. 2017;6:e23845. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson PJL, Richardson DJ, Codd R. The periplasmic nitrate reductase in Shewanella: the resolution, distribution and functional implications of two NAP isoforms, NapEDABC and NapDAGHB. Microbiology. 2010;156:302–312. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.034421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dias JM, et al. Crystal structure of the first dissimilatory nitrate reductase at 1.9 Å solved by MAD methods. Structure. 1999;7:65–79. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Hay ID, Rehman ZU, Rehm BHA. Membrane-anchored MucR mediates nitrate-dependent regulation of alginate production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:7253–7265. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6591-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris HW, El-Naggar MY, Nealson KH. Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 chemotaxis proteins and electron-transport chain components essential for congregation near insoluble electron acceptors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40:1167–1177. doi: 10.1042/BST20120232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bencharit S, Ward MJ. Chemotactic responses to metals and anaerobic electron acceptors in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:5049–5053. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.14.5049-5053.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meysman FJR, Risgaard-Petersen N, Malkin SY, Nielsen LP. The geochemical fingerprint of microbial long-distance electron transport in the seafloor. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 2015;152:122–142. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2014.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Orcutt BN, et al. Microbial activity in the marine deep biosphere: progress and prospects. Front. Microbiol. 2013;4:189. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatton, A., Malin, G., Turner, S. & Liss, P. In Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds (eds. Kiene, R. P., Visscher, P. T., Keller, M. D. & Kirst, G. O.) 405–412 (Plenum Press, 1996).

- 39.Moran MA, Durham BP. Sulfur metabolites in the pelagic ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17:665–678. doi: 10.1038/s41579-019-0250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kettle AJ, Andreae MO. Flux of dimethylsulfide from the oceans: a comparison of updated data sets and flux models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000;105:26793–26808. doi: 10.1029/2000JD900252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malin G, Kirst GO. Algal production of dimethyl sulfide and its atmospheric role. J. Phycol. 1997;33:889–896. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1997.00889.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Deng J, et al. Divergence in gene regulation contributes to sympatric speciation of Shewanella baltica strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;84:e02015–e02017. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02015-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deng J, et al. Stability, genotypic and phenotypic diversity of Shewanella baltica in the redox transition zone of the Baltic Sea. Environ. Microbiol. 2014;16:1854–1866. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sunda W, Kieber DJ, Kiene RP, Huntsman S. An antioxidant function for DMSP and DMS in marine algae. Nature. 2002;418:317–320. doi: 10.1038/nature00851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petit M, et al. Dynamic of bacterial communities attached to lightened phytodetritus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015;22:13681–13692. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teske, A. & Nelson, D. C. In The Prokaryotes. 784–810 (Springer New York, 2006).

- 47.Szpak P, Millaire JF, White CD, Longstaffe FJ. Influence of seabird guano and camelid dung fertilization on the nitrogen isotopic composition of field-grown maize (Zea mays) J. Archaeol. Sci. 2012;39:3721–3740. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2012.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatton AD, Wilson ST. Particulate dimethylsulphoxide and dimethylsulphoniopropionate in phytoplankton cultures and Scottish coastal waters. Aquat. Sci. 2007;69:330–340. doi: 10.1007/s00027-007-0891-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Speeckaert G, Borges AV, Champenois W, Royer C, Gypens N. Annual cycle of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) related to phytoplankton succession in the Southern North Sea. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;622:362–372. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zehr JP, Ward BB. Nitrogen cycling in the ocean: new perspectives on processes and paradigms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:1015–1024. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1015-1024.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baraquet C, Théraulaz L, Iobbi-Nivol C, Méjean V, Jourlin-Castelli C. Unexpected chemoreceptors mediate energy taxis towards electron acceptors in Shewanella oneidensis. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73:278–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nealson KH, Moser DP, Saffarini DA. Anaerobic electron acceptor chemotaxis in Shewanella putrefaciens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995;61:1551–1554. doi: 10.1128/AEM.61.4.1551-1554.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harris HW, El-Naggar MY, Nealson KH. Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 chemotaxis proteins and electron-transport chain components essential for congregation near insoluble electron acceptors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2012;40:1167–1177. doi: 10.1042/BST20120232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang M, Ginn BR, DiChristina TJ, Stack AG. Adhesion of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 to iron (oxy)(hydr)oxides: microcolony formation and isotherm. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010;44:1602–1609. doi: 10.1021/es901793a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marsili E, et al. Shewanella secretes flavins that mediate extracellular electron transfer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3968–3973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710525105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drewniak L, Stasiuk R, Uhrynowski W, Sklodowska A. Shewanella sp. O23S as a driving agent of a system utilizing dissimilatory arsenate-reducing bacteria responsible for self-cleaning of water contaminated with arsenic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:14409–14427. doi: 10.3390/ijms160714409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barchinger SE, et al. Regulation of gene expression in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 during electron acceptor limitation and bacterial nanowire formation. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016;82:5428–5443. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01615-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aigle A, Bonin P, Iobbi-Nivol C, Méjean V, Michotey V. Physiological and transcriptional approaches reveal connection between nitrogen and manganese cycles in Shewanella algae C6G3. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:44725. doi: 10.1038/srep44725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aigle A, et al. The nature of the electron acceptor (MnIV/NO3) triggers the differential expression of genes associated with stress and ammonium limitation responses in Shewanella algae C6G3. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018;365:fny068. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Teal TK, Lies DP, Wold BJ, Newman DK. Spatiometabolic stratification of Shewanella oneidensis biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:7324–7330. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01163-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Beliaev AS, et al. Global transcriptome analysis of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 exposed to different terminal electron acceptors. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7138–7145. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.7138-7145.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simm R, Morr M, Kader A, Nimtz M, Römling U. GGDEF and EAL domains inversely regulate cyclic di-GMP levels and transition from sessility to motility. Mol. Microbiol. 2004;53:1123–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martín-Rodríguez AJ, et al. On the influence of the culture conditions in bacterial antifouling bioassays and biofilm properties: Shewanella algae, a case study. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:102. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Whelan S, Goldman N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001;18:691–699. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar ,S, Stecher ,G, Li ,M, Knyaz ,C, Tamura ,K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen S, et al. AfterQC: automatic filtering, trimming, error removing and quality control for fastq data. BMC Bioinform. 2017;18:80. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1469-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kopylova E, Noé L, Touzet H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3211–3217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]