Abstract

Background:

Bone-only (BO) metastatic breast cancer (MBC) is considered a more favorable entity than other MBC presentations. However, only few retrospective series and data from selected randomized controlled trials have been reported so far.

Methods:

Using the French national multicenter ESME (Epidemiological Strategy and Medico Economics) Data Platform, the primary objective of our study was to compare the overall survival (OS) of patients with BO versus non-BO MBC at diagnosis, with adjustment on main prognostic factors using a propensity score. Secondary objectives were to compare first-line progression-free survival (PFS1), describe treatment patterns, and estimate factors associated with OS.

Results:

Out of 20,095 eligible women, 5041 (22.4%) patients had BO disease [hormone-receptor positive (HR+)/human epidermal growth-factor-receptor-2 negative (HER2−), n = 4 102/13,229 (31%); HER2+, n = 644/3909 (16.5%); HR−/HER2−, n = 295/2 957 (10%)]. BO MBC patients had a better adjusted OS compared with non-BO MBC [52.1 months (95% confidence interval (CI) 50.3–54.1) versus 34.7 months (95% CI 34.0–35.6) respectively]. The 5-year OS rate of BO MBC patients was 43.4% (95% CI 41.7–45.2). They also had a better PFS1 [13.1 months (95% CI 12.6–13.8) versus 8.5 months (95% CI 8.3–8.7), respectively]. This observation could be repeated in all subtypes. BO disease was an independent prognostic factor of OS [hazard ratio 0.68 (95% CI 0.65–0.72), p < 0.0001]. Results were concordant in all analyses.

Conclusion:

BO MBC patients have better outcomes compared with non-BO MBC, consistently, through all MBC subtypes.

Keywords: bone-only, metastatic breast cancer, outcomes, overall survival, real-life, treatments

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer deaths in women worldwide.1 Bone is the most frequent site of breast cancer metastasis, reaching up to 60–80% of metastatic breast cancer (MBC) patients. Bone involvement is the inaugural site of metastatic disease in 25–40% of MBC patients.2,3

Patients with bone-only (BO) metastases, defined as bone as unique site of metastasis at MBC diagnosis, are a unique subset of MBC patients representing up to 51% of patients with bone relapse.4 Despite their significant number, these patients are regularly excluded from clinical trials given BO metastases are usually non-measurable per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria. In addition, genomic data on BO MBC are nonexistent, as sequencing based on bone biopsies is challenging. Consequently, tailored therapeutic strategies are limited and not so well defined.

Subgroup analyses of clinical trials, with limited sample sizes, suggest that hormone-receptor-positive (HR+) BO MBC has a different natural history and carries a better prognosis compared with non-BO disease.5–8 Conversely, some others do not confirm these findings.9–11 In HR-negative (HR−) or human epidermal growth-factor-receptor-2 positive (HER2+) subtypes, data are even more scarce. Recently, two studies have reported that BO metastatic patients had improved outcome in terms of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) compared with other subsets such as MBC with visceral disease.12,13 These studies represented a selected population from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or a referral center and therefore a potentially biased view of real life.

With only a few, mainly single-center or selected studies available in BO MBC patients, a number of unsolved questions affects daily practices. We aimed at providing the largest comprehensive analysis of BO MBC outcomes and management reported so far in a real-life setting.

Methods

Study design

This non-interventional, retrospective, comparative study was carried out to describe the outcome of predefined MBC patients selected in the ESME-MBC database. This database is an ongoing unique national cohort gathering real-life individual retrospective data from all consecutive patients, male or female, ⩾18 years, having started an anti-cancer treatment for a MBC in 1 of the 18 cancer centers participating in the ESME research program, from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2016. Patient-related data, hospitalization-related data and pharmacy-related data are collected, including patient demographic characteristics, pathology, and outcomes. Treatment strategies are also recorded, including chemotherapy, targeted agents, endocrine therapy (ET), radiotherapy (RT) or other local treatments, as well as supportive therapies such as bone-targeted agents (BTAs).

In the present study, patient selection focused on female BO MBC patients with full immunohistochemistry (IHC) data available regarding HR and HER2 status. Data were compiled until the cut-off date (15 October 2018), death (if this occurred before the cut-off date), or date of last contact (if lost to follow up).

The present analysis was approved by an independent ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est II- 2015-79). No formal dedicated informed consent was required, but all patients had approved the reuse of their electronically recorded data. In compliance with French regulations, the ESME-MBC database was authorized by the French data protection authority (Registration ID 1704113 and authorization number DE-2013.-117) and managed by UNICANCER R&D in accordance with the best current practice guidelines.14,15

Objectives and endpoints

The primary objective of the present study was to compare the OS of BO MBC versus non-BO MBC patients, adjusted using a propensity score, globally, and among the three major MBC subtypes. The secondary objectives were to compare the first-line PFS (PFS1) between BO MBC versus non-BO MBC patients, to describe treatment patterns, and to estimate prognostic factors associated with OS.

OS was the primary endpoint and was defined as time between index date (date of metastatic disease diagnosis) and date of death (from any cause) or date of last contact. PFS1 was defined as time between the starting date of first-line treatment and date of first disease progression, or date of death or date of last contact. A treatment line was defined as a given therapeutic strategy set up until progression, and therefore could involve several treatments including chemotherapy or targeted agents or ET. De novo metastatic disease was defined as presence of metastasis at the time or within 6 months (180 days) of primary tumor diagnosis.

Tumor subtype assessment and evaluation

Standard guidelines were applied to any analysis performed within the ESME database. HER2 and HR statuses were derived from existing results about metastatic tissue sampling if available, or, if not available, from last sampling on early disease. Breast cancer was HR+ if estrogen receptor or progesterone receptor expression was ⩾10% (immunohistochemistry). HER2 immunohistochemical (IHC) score 3+ or IHC score 2+ with a positive fluorescence in situ hybridization or chromogenic in situ hybridization classified the tumors as HER2+.

Statistical analyses

Quantitative variables were described using median or mean, when appropriate, and standard deviation (SD). Qualitative variables were described using frequencies and percentages. The number of missing data was presented, but not considered for the percentage calculations. Patients characteristics were compared between the groups using a chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables, and Student’s t test or non-parametric Wilcoxon test for quantitative variables. All statistical tests were bilateral. All reported p values were two sided and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Both OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were generated. Survival distribution was compared between groups using the log-rank test and adjusted by the inverse probability of treatment weights (IPTW) method.16 The reverse Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the median follow-up duration. Time estimates and hazard ratios were presented with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI).

A minimum set of variables was selected by univariate Cox proportional hazard ratio analysis. Only variables with a p value <0.25 were introduced in the multivariate model. A multivariate analysis using a Cox model adjusted and stratified for prognostic factors of survival and potential confounders was then performed. Prognostic factors for which the proportional hazards assumption was violated (namely significant interaction of covariate with time) were introduced as stratification factors, and factors for which the proportional hazards assumption was verified were included as covariates. The Cox multivariate model was constructed using a backward strategy of variables selection, by retaining only variables that were significant at the 5% level. The relative risks (hazard ratio) associated with each factor, with their 95% CI, are presented.

A propensity score was built to validate the multivariate Cox proportional hazard ratio analysis, to reduce selection bias, and adjust for difference between groups, in order to approximate a randomized trial.17,18 The propensity score was defined as the predicted probability for a patient to have BO disease at metastatic diagnosis. The selected variables in relation to survival were pre-specified factors predicting for OS: metastatic location (BO versus non-BO), age at metastatic diagnosis, grade, tumor subtype, metastatic-free interval (MFI), adjuvant treatment, modality of metastatic diagnosis, period of care. The IPTW method was used, with stabilized weights on survival to make the metastatic location independent of baseline covariates. Propensity score one-to-one matching analyses were also realized to estimate BO effect by directly comparing outcomes between subjects of the matched samples.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® software package Version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patients and follow up

Out of the 22,463 MBC patients in the ESME database, 20,095 patients met the inclusion criteria for the present study. The flowchart is presented in Figure 1. A total of 5041 (25.1%) patients had BO disease, and 15,054 (74.9%) had non-BO disease. Median follow up was 52.43 months (95% CI 50.82–54.24) and 50.92 months (95% CI 49.74–51.87) in BO and non-BO patients, respectively. BO disease represented 31%, 16.5% and 10% of HR+/HER2−, HER2+ and HR−/HER2− MBC subgroups, respectively. HR+/HER2− disease was predominant in BO MBC patients (n = 4102, 81.4%), while 644 (12.8%) and 295 (5.9%) patients had HER2+ and HR−/HER2− disease, respectively. Among the HER2+ BO MBC patients, 526 (81.7%) had a positive HR status. Clinical and pathologic features of the global cohort at metastatic diagnosis are shown in Table 1. Compared with non-BO MBC patients, BO MBC patients were older (mean age 61.0 years versus 59.5 years, p < 0.0001). De novo metastatic disease occurred more frequently in BO than in non-BO MBC patients (37.9% versus 29.2%; p < 0.0001). The mean MFI was 57.76 months (SD 76.25) and 63.62 months (SD 82.19) in BO and non-BO cohorts, respectively (p < 0.0001). Among BO MBC patients, 2023 (40.1%) patients never developed extra-osseous metastases along their disease course. Patient characteristics according to MBC subtypes at metastatic diagnosis and at primary BC diagnosis are included in the Supplemental Tables 1 and 2. BO MBC patient characteristics at primary diagnosis and at metastatic BC diagnosis, according to visceral metastases development, are presented in the Supplemental Tables 3 and 4.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

BO, bone only; ESME, Epidemiological Strategy and Medico Economics; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormonal receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at diagnosis of metastatic disease.

| Characteristics | Overall population | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BO, n = 5041 | Non-BO, n = 15,054 | p value | |

| Mean (SD) age, years | 61.05 (13.52) | 59.54 (13.85) | <0.0001 |

| Subtype, n (%) | |||

| HR+/HER2− | 4102 (81.4) | 9127 (60.6) | <0.0001 |

| HER2+ | 644 (12.8) | 3265 (21.7) | |

| HR−/HER2− | 295 (5.9) | 2662 (17.7) | |

| Metastatic-free interval | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57.76 (76.25) | 63.62 (82.19) | <0.0001 |

| ⩽6 months, n (%) | 1909 (37.9) | 4399 (29.2) | <0.0001 |

| 6–24 months, n (%) | 432 (8.6) | 2223 (14.8) | |

| >24 months, n (%) | 2 700 (53.6) | 8432 (56) | |

| Metastatic status, n (%) | |||

| De novo | 1909 (37.9) | 4399 (29.2) | <0.0001 |

| Recurrent | 3132 (62.1) | 10,655 (70.8) | |

| Modality of MBC diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Systematic examination | 2610 (53.1) | 8016 (54.9) | 0.0232 |

| Symptom | 2307 (46.9) | 6573 (45.1) | |

| Missing | 124 | 465 | |

| Type of metastases, n (%) | |||

| Non-visceral | 5041 (100) | 3439 (22.8) | <0.0001 |

| Visceral non-cerebral | 0 (0) | 10,165 (67.5) | |

| Visceral cerebral | 0 (0) | 1450 (9.6) | |

| Number of metastatic sites | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.00 (0.00) | 2.05 (1.14) | <0.0001 |

| <3, n (%) | 5041 (100) | 10,797 (71.7) | <0.0001 |

| ⩾3, n (%) | 0 (0) | 4257 (28.3) | |

| Period of care (years), n (%) | |||

| – | 2244 (44.5) | 6423 (42.7) | 0.0218 |

| 2012–2016 | 2797 (55.5) | 8631 (57.3) | |

BO, bone only; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; MBC, metastatic breast cancer; SD, standard deviation.

Overall survival

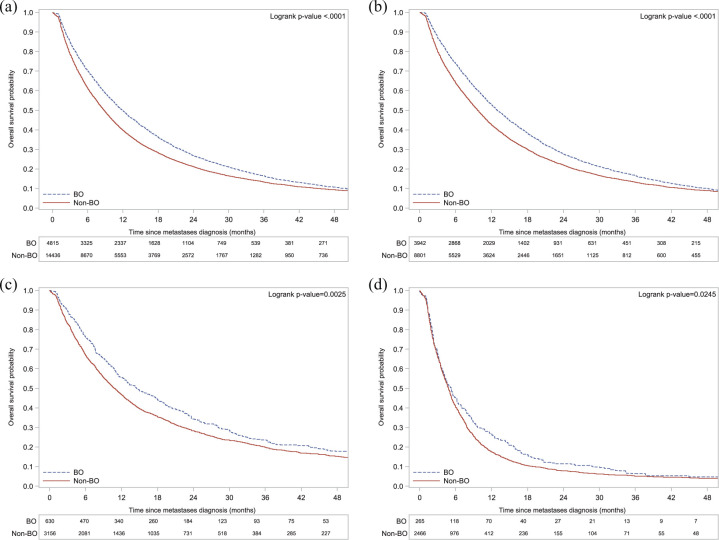

BO MBC patients had a better median OS compared with non-BO MBC, globally [52.1 months (95% CI 50.3–54.1) versus 34.7 months (95% CI 34.0–35.6)] and within each tumor subtype group (Table 2). Indeed, 5-year OS rates were higher in all BO MBC subtype groups as compared with their non-BO MBC counterparts: 43.5%, 54.5%, and 16.2% in HR+/HER2−, HER2+ and HR−/HER2− BO MBC patients versus 32.7%, 39.9%, and 10.9% in non-BO MBC patients, respectively. Figure 2 shows OS curves, adjusted using a propensity score.

Table 2.

Median OS, median PFS1 and OS rates in the overall population and within tumor subtypes.

| Population | BO | Non-BO | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Median OS months (95% CI) | Median PFS1 months (95% CI) | 5-year OS rate % (95% CI) | n (%) | Median OS months (95% CI) | Median PFS1 months (95% CI) | 5-year OS rate % (95% CI) | |

| Overall population | 5041 (100) | 52.1 (50.3–54.1) | 13.1 (12.6–13.8) | 43.4 (41.7–45.2) | 15 054 (100) | 34.7 (34.0–35.6) | 8.5 (8.3–8.7) | 30.6 (29.6–31.5) |

| HR+/HER2− | 4102 (81.4) | 52.6 (50.5–54.8) | 13.6 (13.0–14.3) | 43.5 (41.6–45.5) | 9 127 (60.6) | 39.0 (37.8–40.1) | 9.6 (9.3–9.9) | 32.7 (31.5–33.9) |

| HER2+ | 644 (12.8) | 66.4 (59.8–71.9) | 14.9 (12.9–17.3) | 54.5 (49.5–59.2) | 3 265 (21.7) | 46.5 (44.2–48.9) | 10.6 (10.1–11.3) | 39.9 (37.8–42.0) |

| HR−/HER2− | 295 (5.9) | 20.8 (18.3–27.4) | 5.6 (4.9–7.5) | 16.2 (11.2–22.0) | 2 662 (17.7) | 14.3 (13.6–15.1) | 4.8 (4.6–5.0) | 10.9 (9.4–12.5) |

BO, bone only; CI, confidence interval; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; OS, overall survival; PFS1, first-line progression-free survival.

Figure 2.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival (OS) in the overall population and in each tumor subtype group by location of metastatic disease.

(a) Overall population; (b) HR+/HER2− cohort; (c) HER2+ cohort; (d) HR−/HER2− cohort.

BO, bone only; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor.

We also analyzed OS in BO MBC patients who never developed extra-osseous metastases along their disease course: median OS in these 2023 patients was not yet reached (95% CI 90.8–NE; NE indicates the value could not be estimated), whereas it was 45.3 months (95% CI 43.6–46.9) in the 3018 BO MBC patients who ended up developing visceral metastases [hazard ratio 0.49 (95% CI 0.44–0.54), p < 0,0001].

Regarding treatment effects, OS was higher in the 3913 BO MBC patients who received BTAs compared with the 1128 patients who did not [54.4 months, 95% CI (52.6–56.5) versus 42.7 months, 95% CI (40.1–45.9), respectively; hazard ratio 0.69, 95% CI (0.62–0.76); p < 0.0001].

First-line progression-free survival and systemic treatment

BO MBC patients had also a better median first-line progression-free survival (PFS1) compared with non-BO MBC, globally [13.1 months (95% CI 12.6–13.8) versus 8.5 months (95% CI 8.3–8.7)] and within each tumor subtype group (Table 2). Figure 3 shows PFS1 curves, adjusted using a propensity score.

Figure 3.

Adjusted Kaplan–Meier curves of first-line progression-free survival (PFS1) in the overall population and in each tumor subtype group by location of metastatic disease.

(a) Overall population; (b) HR+/HER2− cohort; (c) HER2+ cohort; (d) HR−/HER2− cohort.

BO, bone only; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor.

For HR+/HER2− BO MBC patients, front-line ET alone was prescribed in 2446 (59.6%) patients while 1341 (32.7%) received combination or sequential therapy (at least two treatments among chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and ET) as first-line systemic treatment (Table 3). This differed from HR+/HER2− non-BO MBC patients with 3330 (36.5%) and 4297 (47.1%) patients, respectively (p < 0.0001). Management differed significantly according to tumor subtype group (Supplemental Table 5).

Table 3.

Treatment patterns according to study group.

| Treatments | Overall population | HR+/HER2− | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BO, n = 5041 | Non-BO, n = 15,054 | p value | BO n = 4102 | Non-BO, n = 9127 | p value | |

| Systemic treatments | ||||||

| Median number of treatment lines (range) | 2.0 (0–14.0) | 2.0 (0–15.0) | 3.0 (0–14.0) | 2.0 (0–15.0) | ||

| First-line treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Any kind | 4981 (98.8) | 14,854 (98.7) | 0.452 | 4068 (99.2) | 9081 (99.5) | 0.0258 |

| Endocrine therapy alone | 2571 (51) | 3629 (24.1) | <0.0001 | 2446 (59.6) | 3330 (36.5) | <0.0001 |

| Combination therapy | 1933 (38.3) | 7837 (52.1) | 1341 (32.7) | 4297 (47.1) | ||

| Chemotherapy alone | 449 (8.9) | 3212 (21.3) | 277 (6.8) | 1446 (15.8) | ||

| Anti-HER2-targeted therapy alone | 28 (0.6) | 176 (1.2) | 4 (0.1) | 8 (0.1) | ||

| Second-line treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Any kind | 3440 (68.2) | 9 920 (65.9) | 0.0023 | 2878 (70.2) | 6342 (69.5) | 0.4348 |

| Endocrine therapy alone | 1053 (20.9) | 1670 (11.1) | <0.0001 | 1018 (24.8) | 1574 (17.2) | <0.0001 |

| Combination therapy | 1314 (26.1) | 3600 (23.9) | 1030 (25.1) | 2181 (23.9) | ||

| Chemotherapy alone | 1012 (20.1) | 4164 (27.7) | 821 (20) | 2536 (27.8) | ||

| Anti-HER2 targeted therapy alone | 61 (1.2) | 486 (3.2) | 9 (0.2) | 51 (0.6) | ||

| Specific management of bone metastases | ||||||

| Bone-targeted agents | ||||||

| n (%) | 3913 (77.6) | 5168 (34.3) | <0.0001 | 3308 (80.6) | 3818 (41.8) | <0.0001 |

| Time (months) to treatment start: mean (SD) | 5.19 (9.15) | 5.65 (9.07) | 0.0273 | 4.97 (8.77) | 5.63 (9.06) | 0.0039 |

| Mean duration (months) of treatment: mean (SD) | 23.89 (17.46) | 17.76 (15.10) | <0.0001 | 24.34 (17.58) | 18.25 (14.99) | <0.0001 |

| Radiotherapy of bone metastases, n (%) | 2929 (58.1) | 2938 (19.5) | <0.0001 | 2390 (58.3) | 2080 (22.8) | <0.0001 |

| Invasive bone metastasis procedure, n (%) | ||||||

| Any kind | 1154 (22.9) | 904 (6) | <0.0001 | 966 (23.5) | 655 (7.2) | <0.0001 |

| Vertebroplasty/cementoplasty | 668 (13.3) | 543 (3.6) | 0.3184 | 576 (14) | 408 (4.5) | 0.2814 |

| Total hip replacement/osteosynthesis | 516 (10.2) | 381 (2.5) | 0.2436 | 416 (10.1) | 268 (2.9) | 0.3901 |

| Metastasectomy | 47 (0.9) | 26 (0.2) | 0.1452 | 41 (1) | 18 (0.2) | 0.1145 |

| Radiofrequency, cryoablation, microwaves | 43 (0.9) | 18 (0.1) | 0.0213 | 32 (0.8) | 14 (0.2) | 0.1620 |

BO, bone only; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; SD, standard deviation.

Among the HR+/HER2− BO MBC patients who received ET alone or in combination as first-line treatment (n = 3688), most (n = 2944, 79.8%) had aromatase inhibitors (AIs), while 985 (26.7%) received tamoxifen, and 453 (12.3%) received fulvestrant. In our subgroup of endocrine-naïve HR+/HER2− BO MBC patients (n = 1511), 44 (2.9%) received fulvestrant as first-line treatment, and mean fulvestrant duration was 10.1 months. Besides, only few patients received cyclin-dependent kinase 4 and 6 (CDK 4/6) inhibitors as first-line treatment [n = 43 (0.7%) in the non-BO population and n = 18 (1.1%) in the BO population].

Among the HER2+ MBC patients (n = 3909), 988 (25.3%) received pertuzumab as first-line treatment. PFS1 was 20.0 months (95% CI 17.9–22.5) in patients who received pertuzumab versus 10.1 months (95% CI 9.5–10.7) in patients who did not [hazard ratio 0.57 (95% CI 0.52–0.63); p < 0.0001]. Among the same population, 391 (10.0%) patients received trastuzumab emtansine (TDM-1) as second-line treatment. PFS2 was 8.5 months (95% CI 7.1–10.4) in patients who received TDM-1 versus 5.7 months (95% CI 5.5–6.2) in patients who did not [hazard ratio 0.70 (95% CI 0.62–0.79); p < 0.0001].

Management of bone metastases in BO MBC

The management of bone disease included BTAs, radiotherapy, and invasive bone metastasis procedures in 3913 (77.6%), 2929 (58.1%), and 1154 (22.9%) patients, respectively (Table 3). Only 56.6% of HR−/HER2− patients received BTA versus 80.6% of HR+/HER2− and 68% of HER2+ patients. Mean time between bone metastasis diagnosis and start of BTA was 5.19 months (SD 9.15) in the global BO MBC population, and ranged from 4.97 to 6.62 months within tumor subtype groups. Mean BTA therapy duration was 23.89 (SD 17.46) and 17.76 (SD 15.10) months in BO and non-BO MBC patients, respectively (p < 0.0001). Of note, 90 patients underwent a procedure with a curative intent.

Multivariate analyses of OS

BO disease was an independent prognostic factor of OS (hazard ratio 0.68; 95% CI 0.65–0.72, p < 0.0001) together with age, tumor subtype, grade, adjuvant treatment, MFI, and symptomatic disease at metastatic diagnosis (Table 4). BO disease was also associated with a better prognosis within each tumor subtype group (Supplemental Table 6).

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox-model analysis of overall survival in the overall population.

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Bone only disease | ||

| No | Reference | _ |

| Yes | 0.68 (0.65–0.72) | <0.0001 |

| Age at metastatic diagnosis | ||

| <50 years | Reference | _ |

| 50–70 years | 1.22 (1.16–1.29) | <0.0001 |

| >70 years | 1.78 (1.67–1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Adjuvant CT/TT | ||

| No | Reference | _ |

| Yes | 1.30 (1.22–1.38) | <0.0001 |

| Grade III | ||

| No | Reference | _ |

| Yes | 1.30 (1.24–1.36) | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic-free interval | ||

| <6 months | Reference | _ |

| 6–24 months | 1.79 (1.66–1.93) | <0.0001 |

| >24 months | 0.98 (0.92–1.05) | 0.5839 |

| Tumor subtype | ||

| HR−/HER2− | Reference | _ |

| HR+/HER2− | 0.49 (0.46–0.52) | <0.0001 |

| HER2+ | 0.36 (0.33–0.38) | <0.0001 |

| Modality of metastatic diagnosis | ||

| Systematic examination | Reference | _ |

| Symptom | 1.20 (1.15–1.26) | <0.0001 |

CI, confidence interval; CT, chemotherapy; HER2, human epidermal growth-factor-receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; TT, targeted therapy (trastuzumab).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest comprehensive real-life multicenter cohort of BO MBC to date. We show that MBC patients with BO disease have a different disease trajectory, with much higher median OS than non-BO MBC patients. The 5-year OS rate of BO MBC patients was 43.4%, suggesting that a substantial number of these patients could be considered long survivors, and may benefit from aggressive local therapy.

Our findings are consistent with prior published results by Niikura et al.,13 Ahn et al.19 and Parkes et al.,20 with median OS ranging from 51 to 59 months, and surprisingly higher than that seen in clinical trial patients.12 These are also much higher OS rates than those previously reported in older studies,21,22 underlining the therapeutic progresses in the management of BO MBC patients nowadays. Whether this better prognosis is due to a specific biology of the bone microenvironment still needs to be evaluated.

These important observations raise the question of the accurate management of bone disease and its potential impact on outcome of patients. BTAs have modified bone disease management by reducing skeletal-related event (SRE) incidence and bone pain and delaying the median time to an SRE.23–26 However, a recent meta-analysis showed no effect of BTA on OS in MBC with bone metastases.27 In the present study, BTA therapy in BO MBC patients seemed to increase OS. This is important information, as no prospective data are available in this specific population. We observed discrepancies between tumor subtypes, suggesting that some patients with bone disease are still not receiving early BTA therapy.

Bone remodeling markers had a cornerstone role in the development of BTA.28 They have mainly been studied in preclinical research or in clinical trials, but their impact in routine practice remains to be demonstrated. They could be helpful to better define the ongoing risk for bone complications after 2 years of BTAs. They could also be particularly useful in the early-disease setting in identifying patients with a high risk of developing bone metastases.29 Even if some biomarkers offer promising results, their sensitivity and specificity are low, and their use is not recommended in current practice guidelines.30–32

Radiotherapy was performed in 2929 (58.1%) patients. Stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) treatment was not an available datum of the database and we could not investigate whether oligometastatic BO MBC treated by SBRT had an improved OS compared with those treated with non-stereotactic radiotherapy. A French phase III RCT evaluating SBRT added to standard treatment versus standard treatment alone in solid tumor (including breast cancer) patients with one to three BO metastases is currently recruiting patients (STEREO-OS) [ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03143322] and should answer this important question. Finally, impact of invasive bone metastasis procedures with a curative intent on outcome was not evaluable, given the population size.

HR+/HER2− disease accounts for the majority of BO MBC patients as seen in earlier studies.12,13 In the ESME database, 31% of HR+/HER2− patients had BO disease, which is consistent with recently released clinical trial HR+/HER2− populations in which percentages reached up to 27% of MBC patients.7–9,11 As for the management of patients, 3688 (90%) HR+/HER2− BO MBC patients received ET as first-line treatment. This is in agreement with current international guidelines.33 Indeed, bone disease is not at immediate vital risk, and thus does not require disease control as promptly as extensive visceral disease. Some reports have underlined a great benefit of ET alone in BO MBC. In the Falcon trial, postmenopausal HR+ MBC patients with non-visceral disease who had not received previous ET had a median PFS of 22.3 months (95% CI 16.62–32.79) in the fulvestrant group versus 13.8 months (95% CI 11.04–16.59) in the anastrozole group.5 We do not confirm such a benefit of fulvestrant in the present study. In recent years, CDK 4/6 inhibitors emerged in combination with ET in HR+/HER2− MBC, showing improvement of PFS, and recently of OS.7,9,11,34–38 Some phase III trials exploring the efficacy of CDK 4/6 inhibitors in MBC found a significant improvement in PFS or OS in BO or non-visceral MBC subgroups, while other trials did not confirm these data.34–38 A recent meta-analysis confirmed the efficacy of CDK 4/6 inhibitors in BO MBC, with an improvement in PFS (hazard ratio 0.54; 95% CI 0.39–0.75, p < 0.001), in particular for palbociclib (hazard ratio 0.36; 95% CI 0.22–0.59, p < 0.001), and an acceptable toxicity profile.39 In our study, no specific analysis could be done regarding CDK 4/6 inhibitors, given the population size.

Beside HR+/HER2− disease, a small proportion of HER2+ MBC has BO MBC at initial presentation. These patients carry the best prognosis with a 5-year OS rate of 54%. Multivariate analyses showed that period of care was an independent predictor of OS in this population. Indeed, HER2+ patients treated between 2012 and 2016 had a significantly improved prognosis compared with those treated from 2008 to 2011 (hazard ratio 0.76; 95% CI 0.69–0.85, p < 0.0001). This has been shown previously by Gobbini et al.,40 and corresponds to recent drug approvals, such as pertuzumab and TDM-1. Our results are consistent with those of the CLEOPATRA and EMILIA trials.41,42

Only 5.9% of BO MBC patients were HR−/HER2−, which is fewer than the usual 10–15% described in MBC patients,43 but in alignment with Kennecke et al., who found a significant lower risk of bone relapse for HR−/HER2− MBC patients.44

It is also important to highlight that BO MBC patients were more frequently diagnosed because of symptoms (n = 2307, 46.9%) than non-BO MBC patients (n = 6573, 45.1%; p = 0.0232), rather than by systematic examination, and therefore may have been diagnosed earlier than non-BO MBC patients. This could partially explain why de novo metastatic disease occurred more frequently in BO than in non-BO MBC patients.

No drugs targeting bone metastases and extending OS have been identified in MBC. The development of successful strategies to treat and possibly prevent bone metastases will depend on a better understanding of the complex cancer metastasis process. Targeted approaches aimed at interfering with the aberrant bone remodeling associated with breast cancer metastases could offer promising results.

We know that disseminating cancer cells initiate growth in premetastatic niches in which tumor cells may later enter in a dormant state45 and that bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer may be an early event for systemic disease.46 Biological mechanisms of bone metastases may differ from those to extra-osseous sites, and identification of distinct signaling pathways and somatic mutations may provide insights on biology and targets for treatment and prevention of bone metastases.47–53 Whether specific mutations are associated with BO MBC is poorly understood. Kono et al. did not find unique somatic mutations associated with de novo BO MBC.54 Comprehensive molecular and genomic analyses are needed to further understand the factors associated with BO MBC. No biological samples were available from the ESME database and we were not able to perform such analyses. Even if bone-specific breast cancer metastasis genes have been identified,55–59 there is no validated gene expression signature yet.

However, our analysis revealed that BO MBC patients who never developed extra-osseous metastases were older at diagnosis, had less grade III tumors, and had more frequently de novo MBC compared with BO MBC patients who developed visceral metastases (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). There was no statistical difference regarding tumor subtype and menopausal status at primary diagnosis between these two groups. Regarding characteristics at diagnosis of metastatic disease, HR+/HER2− disease was predominant in both groups, but HER2+ disease occurred more frequently in BO MBC patients who never developed extra-osseous metastases compared with BO MBC patients who developed visceral metastases, suggesting potential differences in the biology of these tumors. These analyses need to be confirmed.

The ESME-MBC program reports centralized high-quality and exhaustive real-life data, with a clinical-trial-like methodology, representing a very largescale ongoing multicenter cohort with more than 24,000 MBC cases to date. It involves 18 French Comprehensive Cancer Centers managing more than one third of all MBC cases in France, giving a reliable view of this single entity in a real-life setting. We should acknowledge that limitations of this study are its retrospective and observational nature, although we showed that our results are in alignment with recent publications, highlighting their reliability. Indeed, we do have missing data, some of which are prognostic factors in this situation, such as the performance status. Another major limitation of this observational study is the lack of randomization. However, to adjust for baseline differences between groups and to reduce the impact of selection bias, a propensity score was built. When we used stabilized weights to adjust, we still observed a differential effect of metastatic location at metastatic diagnosis on OS, with BO patients having a better prognosis.

This large comprehensive retrospective study is the largest cohort of BO MBC to date. Taken together, our results are consistent with prior studies and show that BO MBC is a specific entity, having a distinct presentation, and a better prognosis than non-BO MBC. A significant proportion of BO MBC patients have a very long survival and may benefit from aggressive local therapy. Clinical oncology is advancing toward a more personalized medicine but clinical management of bone metastases from breast cancer remains challenging. Dedicated studies are warranted to tailor the management of BO MBC patients. The use of biomarkers and molecular and genomic analyses would be very useful to better define our therapeutic strategies in this population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-3-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-4-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-5-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-6-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Acknowledgments

The results of the present article have been presented in part at the 2019 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium:

Bertho M, Fraisse J, Patsouris A, et al. Abstract P2-19-01: Impact of bone-only metastatic breast cancer on outcome in a real-life setting: a comprehensive analysis of 5,041 women from the ESME database. Cancer Res 2020; 80 (4).

We thank the 18 French Comprehensive Cancer Centers for providing the data and each ESME local coordinator for managing the project at the local level. Moreover, we thank the ESME Scientific Committee members for their ongoing support.

The 18 Participating French Comprehensive Cancer Centers are: I Curie, Paris/Saint-Cloud; G Roussy, I Villejuif, Cancérologie de l’Ouest, Angers/Nantes; CF Baclesse, Caen, ICM Montpellier; CL Bérard, Lyon; CG-F Leclerc, Dijon; CH Becquerel, Rouen; IC Regaud, Toulouse; CA Lacassagne, Nice; Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine, Nancy; CE Marquis, Rennes; I Paoli-Calmettes, Marseille; CJ Perrin, Clermont Ferrand; I Bergonié, Bordeaux; CP Strauss, Strasbourg; IJ Godinot, Reims; CO Lambret, Lille. We thank the 18 French Comprehensive Cancer Centers for providing the data and each ESME contact for coordinating the project at the local level.

ESME central coordinating staff:

Head of Research and Development: Claire Labreveux.

Program director: Mathieu Robain.

Data management team: Coralie Courtinard, Emilie Nguyen, Olivier Payen, Irwin Piot, Dominique Schwob, and Olivier Villacroux.

Operational team: Michaël Chevrot, Daniel Couch, Patricia D’Agostino, Pascale Danglot, Cécilie Dufour, Tahar Guesmia, Christine Hamonou, Gaëtane Simon, and Julie Tort.

Supporting clinical research associates: Elodie Kupfer and Toihiri Said.

Project Associate: Nathalie Bouyer.

Management assistant: Esméralda Pereira.

Software designers: Matou Diop, Blaise Fulpin, José Paredes, and Alexandre Vanni.

ESME local coordinators:

Thomas Bachelot, Delphine Berchery, Etienne Brain, Mathias Breton, Loïc Campion, Emmanuel Chamorey, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Stéphanie Delaine, Valérie Dejean, Anne-Valérie Guizard, Anne Jaffré, Lilian Laborde, Carine Laurent, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Agnès Loeb, Muriel Mons, Damien Parent, Geneviève Perrocheau, Marie-Ange Mouret-Reynier, and Michel Velten.

We thank Ludovic Gauthier for his help regarding figures and supplementary analyses.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: MB and JSF designed and conducted the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. JF provided statistical analysis. All authors contributed to completion and revision of the manuscript, and approved the submission of the article.

Conflict of interest statement: P Cottu reports grants from Pfizer and Novartis, personal fees from Pfizer and Eli-Lilly, and non-financial support from Pfizer, outside the submitted work. M Arnedos reports research grants from Eli-Lilly, consultant fees from Novartis, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer and Seattle Genetics, outside the submitted work. D Pérol reports personal fees from Roche, Pierre Fabre, Novartis, BMS, Eli-Lilly, Ipsen, MSD, personal fees and non-financial support from Astra Zeneca, grants from MDS, outside the submitted work. A Goncalves reports non-financial support from Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Roche and Novartis, outside the submitted work. F Penault-Llorca reports non-financial support from Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, Roche, and Eli-Lilly, outside the submitted work. JS Frénel reports personal fees from Roche, Astra Zeneca, Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, GSK, and ESAI and non-financial support from Roche, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, and Novartis, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by UNICANCER R&D. The ESME-MBC database is supported by an industrial consortium (Roche, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, MSD, Eisai and Daiichi Sankyo). Data collection, analyses and publications are totally managed by UNICANCER R&D independently of the industrial consortium.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The present analysis was approved by an independent ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est II- 2015-79). No formal dedicated informed consent was required, but all patients had approved the reuse of their electronically recorded data. In compliance with French regulations, the ESME-MBC database was authorized by the French data protection authority (Registration ID 1704113 and authorization number DE-2013.-117) and managed by UNICANCER R&D in accordance with the best current practice guidelines. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ORCID iDs: Marion Bertho  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6992-9174

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6992-9174

Jean-Sébastien Frénel  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5273-0561

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5273-0561

Data availability: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Marion Bertho, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut de Cancérologie de l’Ouest – Paul Papin, Angers, France.

Julien Fraisse, Biometrics Unit, Regional Cancer Institute of Montpellier (ICM), Montpellier, France.

Anne Patsouris, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut de Cancérologie de l’Ouest – Paul Papin, Angers, France.

Paul Cottu, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Curie, Paris, France.

Monica Arnedos, Department of Medical Oncology, Gustave Roussy Cancer Campus, Villejuif, France.

David Pérol, Biostatistic Unit, Clinical Research and Innovation Department, Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France.

Anne Jaffré, Department of Medical Information, Institut Bergonié, Bordeaux, France.

Anthony Goncalves, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Paoli-Calmettes, Marseille, France.

Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Clinical Research and Innovation Department, Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille, France.

Véronique D’Hondt, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut du Cancer de Montpellier, Montpellier, France.

Florence Dalenc, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Claudius Regaud, IUCT-Oncopole, Toulouse, France.

Jean-Marc Ferrero, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice, France.

Christelle Levy, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre François Baclesse, Caen, France.

Sandrine Dabakuyo, National Quality of Life and Cancer Clinical Research Platform, Centre Georges François Leclerc, Dijon, France.

Roman Rouzier, Department of Surgical Oncology, Institut Curie, Saint-Cloud, France.

Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Department of Pathology and Molecular Pathology, Centre Jean Perrin, Clermont Ferrand, France.

Lionel Uwer, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut de Cancérologie de Lorraine, Vandoeuvre-lès- Nancy, France.

Jean-Christophe Eymard, Department of Medical Oncology, Institut de Cancérologie Jean-Godinot, Reims, France.

Mathias Breton, Department of Medical Information, Centre Eugène Marquis, Rennes, France.

Michaël Chevrot, UNICANCER R&D, Paris, France.

Sébastien Thureau, Department of Radiation Oncology, Centre Henri Becquerel, Rouen, France.

Thierry Petit, Department of Medical Oncology, Centre Paul Strauss, Strasbourg, France.

Gaëtane Simon, UNICANCER R&D, Paris, France.

Jean-Sébastien Frénel, Department of Medical Oncology, ICO René Gauducheau, Boulevard Jacques Monod, Saint Herblain, Pays de la Loire 44805, France.

References

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coleman R, Rubens R. The clinical course of bone metastases from breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1987; 55: 61–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manders K, Van de Poll-Franse LV, Creemers G-J, et al. Clinical management of women with metastatic breast cancer: a descriptive study according to age group. BMC Cancer 2006; 6: 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soni A, Ren Z, Hameed O, et al. Breast cancer subtypes predispose the site of distant metastases. Am J Clin Pathol 2015; 143: 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robertson JFR, Bondarenko IM, Trishkina E, et al. Fulvestrant 500 mg versus anastrozole 1 mg for hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer (FALCON): an international, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 388: 2997–3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Finn RS, Crown JP, Lang I, et al. The cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib in combination with letrozole versus letrozole alone as first-line treatment of oestrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative, advanced breast cancer (PALOMA-1/TRIO-18): a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finn RS, Martin M, Rugo HS, et al. Palbociclib and letrozole in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1925–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. André F, Ciruelos E, Rubovszky G, et al. Alpelisib for PIK3CA-mutated, hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1929–1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR-positive, advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 1738–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sledge GW, Toi M, Neven P, et al. MONARCH 2: abemaciclib in combination with fulvestrant in women with HR+/HER2− advanced breast cancer who had progressed while receiving endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 2875–2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tripathy D, Im S-A, Colleoni M, et al. Ribociclib plus endocrine therapy for premenopausal women with hormone-receptor-positive, advanced breast cancer (MONALEESA-7): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 904–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wedam SB, Beaver JA, Amiri-Kordestani L, et al. US Food and Drug Administration pooled analysis to assess the impact of bone-only metastatic breast cancer on clinical trial outcomes and radiographic assessments. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Parkes A, Clifton K, Al-Awadhi A, et al. Characterization of bone only metastasis patients with respect to tumor subtypes. NPJ Breast Cancer 2018; 4: 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Public Policy Committee, International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP): guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016; 25: 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Association des Epidémiologistes de Langue française (ADELF). Recommandations de déontologie et bonnes pratiques en épidémiologie, recommandations révisées, 2007. http://adelf.isped.u-bordeaux2.fr/Portals/0/DOCUMENTATION/Recommandations_Version_Anglais-Janv.2008.pdf

- 16. Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, et al. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health 2010; 13: 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983; 70: 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18. D’Agostino RB. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998; 17: 2265–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niikura N, Liu J, Hayashi N, et al. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors for patients with bone-only metastases of breast cancer: a single-institution retrospective analysis. Oncologist 2011; 16: 155–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ahn SG, Lee HM, Cho S-H, et al. Prognostic factors for patients with bone-only metastasis in breast cancer. Yonsei Med J 2013; 54: 1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scheid V, Buzdar AU, Smith TL, et al. Clinical course of breast cancer patients with osseous metastasis treated with combination chemotherapy. Cancer 1986; 58: 2589–2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Perez JE, Machiavelli M, Leone BA, et al. Bone-only versus visceral-only metastatic pattern in breast cancer: analysis of 150 patients. A GOCS study. Grupo Oncológico Cooperativo del Sur. Am J Clin Oncol 1990; 13: 294–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hortobagyi GN, Theriault RL, Porter L, et al. Efficacy of pamidronate in reducing skeletal complications in patients with breast cancer and lytic bone metastases. Protocol 19 Aredia Breast Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med 1996; 335: 1785–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosen LS, Gordon D, Kaminski M, et al. Zoledronic acid versus pamidronate in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with breast cancer or osteolytic lesions of multiple myeloma: a phase III, double-blind, comparative trial. Cancer J Sudbury Mass 2001; 7: 377–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 3314–3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body J-J, et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 5132–5139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O’Carrigan B, Wong MH, Willson ML, et al. Bisphosphonates and other bone agents for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 10: CD003474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferreira A, Alho I, Casimiro S, et al. Bone remodeling markers and bone metastases: from cancer research to clinical implications. BoneKEy Rep 2015; 4: 668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brown J, Rathbone E, Hinsley S, et al. Associations between serum bone biomarkers in early breast cancer and development of bone metastasis: results from the AZURE (BIG01/04) trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2018; 110: 871–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Van Poznak C, Somerfield MR, Barlow WE, et al. Role of bone-modifying agents in metastatic breast cancer: an American Society of Clinical Oncology–cancer care ontario focused guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 3978–3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Coleman R, Hall A, Albanell J, et al. Effect of MAF amplification on treatment outcomes with adjuvant zoledronic acid in early breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the international, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 AZURE (BIG 01/04) trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: 1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coleman R, Hadji P, Body J-J, et al. Bone health in cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines†. Ann Oncol. Epub ahead of print 12 August 2020. DOI: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thomssen C, Lüftner D, Untch M, et al. International consensus conference for advanced breast cancer, Lisbon 2019: ABC5 consensus – assessment by a German group of experts. Breast Care 2020; 15: 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Im S-A, Lu Y-S, Bardia A, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Johnston S, Martin M, Di Leo A, et al. MONARCH 3 final PFS: a randomized study of abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019; 5: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rugo HS, Finn RS, Diéras V, et al. Palbociclib plus letrozole as first-line therapy in estrogen receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative advanced breast cancer with extended follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2019; 174: 719–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sledge GW, Toi M, Neven P, et al. The effect of abemaciclib plus fulvestrant on overall survival in hormone receptor–positive, ERBB2-negative breast cancer that progressed on endocrine therapy—MONARCH 2: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020; 6: 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Slamon DJ, Neven P, Chia S, et al. Overall survival with ribociclib plus fulvestrant in advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 514–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Toss A, Venturelli M, Sperduti I, et al. First-line treatment for endocrine-sensitive bone-only metastatic breast cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Breast Cancer 2019; 19: e701–e716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gobbini E, Ezzalfani M, Dieras V, et al. Time trends of overall survival among metastatic breast cancer patients in the real-life ESME cohort. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990 2018; 96: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Swain SM, Baselga J, Kim S-B, et al. Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 724–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Verma S, Miles D, Gianni L, et al. Trastuzumab emtansine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1783–1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA 2019; 321: 288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kennecke H, Yerushalmi R, Woods R, et al. Metastatic behavior of breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3271–3277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ingangi V, Minopoli M, Ragone C, et al. Role of microenvironment on the fate of disseminating cancer stem cells. Front Oncol. Epub ahead of print 21 February 2019. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Braun S, Janni W, Schlimok G, et al. A pooled analysis of bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang XH-F, Wang Q, Gerald W, et al. Latent bone metastasis in breast cancer tied to src-dependent survival signals. Cancer Cell 2009; 16: 67–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rucci N, Sanità P, Delle Monache S, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of bone metastases in breast cancer: proven and emerging therapeutic targets. World J Clin Oncol 2014; 5: 335–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kimbung S, Loman N, Hedenfalk I. Clinical and molecular complexity of breast cancer metastases. Semin Cancer Biol 2015; 35: 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cosphiadi I, Atmakusumah TD, Siregar NC, et al. Bone metastasis in advanced breast cancer: analysis of gene expression microarray. Clin Breast Cancer 2018; 18: e1117–e1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen W, Hoffmann AD, Liu H, et al. Organotropism: new insights into molecular mechanisms of breast cancer metastasis. NPJ Precis Oncol 2018; 2: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang Y, He W, Zhang S. Seeking for correlative genes and signaling pathways with bone metastasis from breast cancer by integrated analysis. Front Oncol. Epub ahead of print 13 March 2019. DOI: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang M, Xia F, Wei Y, et al. Molecular mechanisms and clinical management of cancer bone metastasis. Bone Res 2020; 8: 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kono M, Fujii T, Matsuda N, et al. Somatic mutations, clinicopathologic characteristics, and survival in patients with untreated breast cancer with bone-only and non-bone sites of first metastasis. J Cancer 2018; 9: 3640–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell 2003; 3: 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smid M, Wang Y, Klijn JGM, et al. Genes associated with breast cancer metastatic to bone. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 2261–2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Savci-Heijink CD, Halfwerk H, Koster J, et al. A novel gene expression signature for bone metastasis in breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2016; 156: 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li J-N, Zhong R, Zhou X-H. Prediction of bone metastasis in breast cancer based on minimal driver gene set in gene dependency network. Genes 2019; 10: 466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Luo A, Xu Y, Li S, et al. Cancer stem cell property and gene signature in bone-metastatic breast cancer cells. Int J Biol Sci 2020; 16: 2580–2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-1-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-2-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-3-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-4-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-5-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Supplemental material, sj-xlsx-6-tam-10.1177_1758835920987657 for Real-life prognosis of 5041 bone-only metastatic breast cancer patients in the multicenter national observational ESME program by Marion Bertho, Julien Fraisse, Anne Patsouris, Paul Cottu, Monica Arnedos, David Pérol, Anne Jaffré, Anthony Goncalves, Marie-Paule Lebitasy, Véronique D’Hondt, Florence Dalenc, Jean-Marc Ferrero, Christelle Levy, Sandrine Dabakuyo, Roman Rouzier, Frédérique Penault-Llorca, Lionel Uwer, Jean-Christophe Eymard, Mathias Breton, Michaël Chevrot, Sébastien Thureau, Thierry Petit, Gaëtane Simon and Jean-Sébastien Frénel in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology