Abstract

A new fossil species of pyrgodesmid millipede (Polydesmida: Pyrgodesmidae) placed in the genus Myrmecodesmus Silvestri, 1910 is described. The type materials are two amber inclusions, male and female specimens that come from Miocene strata in Chiapas, Mexico. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov. has collum with 10 dorsal tubercles; without porosteles or ozopores; legs of the rings 2–9 with a short projection on the prefemur in both the female and male. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov is the first fossil record of the genus Myrmecodesmus. This is a New World taxon that belongs to the pantropical family Pyrgodesmidae. Thus, Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov expands the range of the genus to the Miocene tropics in Middle America.

Keywords: Miocene, Mexico, Diplopoda, Pyrgodesmidae, New species

Introduction

The polydesmid millipedes of the family Pyrgodesmidae currently show a Pantropical distribution (Enghoff et al., 2015). However, the fossil record is limited to amber inclusions from Miocene deposits of the Dominican Republic and Mexico (Shear, 1981; Santiago-Blay & Poinar, 1992; Riquelme & Hernández-Patricio, 2018). Fossil specimens of Dominican amber have been assigned to the genera Docodesmus Cook, 1896a, Iomus Cook, 1911, Lophodesmus Pocock, 1894 and Psochodesmus Cook, 1896b (Shear, 1981; Santiago-Blay & Poinar, 1992), and the only fossil specimen described at the species level that is known so far is Docodesmus brodzinskyi Shear, 1981. Another fossil pyrgodesmid was found in Chiapas amber, Mexico, a female specimen identified as CPAL.117 by Riquelme & Hernández-Patricio (2018), which was initially included as a new member of the genus Myrmecodesmus within Pyrgodesmidae. In the present contribution, based on the female CPAL.117 plus another male specimen identified as CPAL.132, a new species of the genus Myrmecodesmus is now described. Below are descriptions, illustrations, and a discussion of related taxa.

Geological setting

The fossil specimens CPAL.117 and CPAL.132 come from the lignite-sandstones beds exposed in a site called Los Pocitos in the town of Simojovel, located approximately 122 km by road from the city of Tuxtla, Chiapas, southwestern Mexico. The amber-bearing beds of Simojovel are generally assigned to the Mazantic and Balumtum strata from early to mid-Miocene (Perriliat, Vega & Coutiño, 2010; Durán-Ruíz et al., 2013; Riquelme et al., 2013). Another outcrop exposed near Los Pocitos in Simojovel that contains fossil amber, is preliminarily considered the upper portion of the La Quinta strata in the late Oligocene (Graham, 1999). Here, a marine sedimentary environment is predominantly observed. The stratigraphic section and lithology of a typical amber outcrop in Chiapas are presented in Durán-Ruíz et al. (2013). It is indicated there that a portion of the marine sandstones of the La Quinta is located between the boundaries of the early Miocene and the late Oligocene. However, the complete geology of all amber deposit in Chiapas is an unresolved issue and the stratigraphic record of amber outcrops must be carefully considered (Durán-Ruíz et al., 2013; Riquelme et al., 2013). We consistently noted in the field that most of the fossil inclusions in Simojovel, Totolapa and Estrella de Belén in the Chiapas Highlands come from lignite-sandstones beds which belong to the Mazantic and Balumtum strata from early to mid-Miocene (Durán-Ruíz et al., 2013; Riquelme et al., 2013, 2014a, 2014b). Simojovel, Totolapa, and Estrella de Belén are considered the type localities of a Conservation Lagerstätte with a remarkable abundance of amber inclusions, predominantly terrestrial arthropods and plants (Riquelme et al., 2013, 2014b). Here the sedimentary record is strongly associated with a lowland-fluvial environment close to the coastal plain (Graham, 1999; Langenheim, 2003; Perriliat, Vega & Coutiño, 2010; Riquelme et al., 2013); and paleobiota resembles those found in current humid tropics (Riquelme & Hernández-Patricio, 2018). Chiapas amber has chemical signatures that match with the extant resins of the genus Hymenaea (sensu Langenheim, 1966), which are also currently distributed in the tropics (Langenheim, 2003; Riquelme et al., 2014b)

Materials and Methods

The fossil specimens treated in this study are listed as CPAL.117 and CPAL.132, housed at the Colección de Paleontología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (CPAL-UAEM), located in Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico. Anatomical terminology follows Hoffman (1976) and Koch (2015), and nomenclature follows Shear (2011). Preparation of material and methods used here are presented in Riquelme et al. (2013). Microphotographs were acquired using multiple image-stacking (Z ≥ 45) in a Carl Zeiss microscope, and schematic drawings were hand traced by electronic pen using a stereomicroscope and Corel Draw X7 for graphic processing. Anatomical measurements are presented in millimeters and were collected using the open-source program tpsDig V. 2.17 (Rohlf, 2013).

The electronic version of this article in Portable Document Format will represent a published work according to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), and hence the new names contained in the electronic version are effectively published under that Code from the electronic edition alone. This published work and the nomenclatural acts it contains have been registered in ZooBank, the online registration system for the ICZN. The ZooBank Life Science Identifiers can be resolved and the associated information viewed through any standard web browser by appending the LSID to the prefix http://zoobank.org/. The LSID for this publication is: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:95759D56-205C-4FD2-A01B-0CE3F9621E0E. The online version of this work is archived and available from the following digital repositories: PeerJ, PubMed Central and CLOCKSS.

Results

Systematic paleontology

Order Polydesmida Pocock, 1887

Suborder Polydesmidea Pocock, 1887

Infraorder Oniscodesmoides Simonsen, 1990

Superfamily Pyrgodesmoidea Silvestri, 1896

Family Pyrgodesmidae Silvestri, 1896

Genus Myrmecodesmus Silvestri, 1910

Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov. Riquelme and Hernández-Patricio.

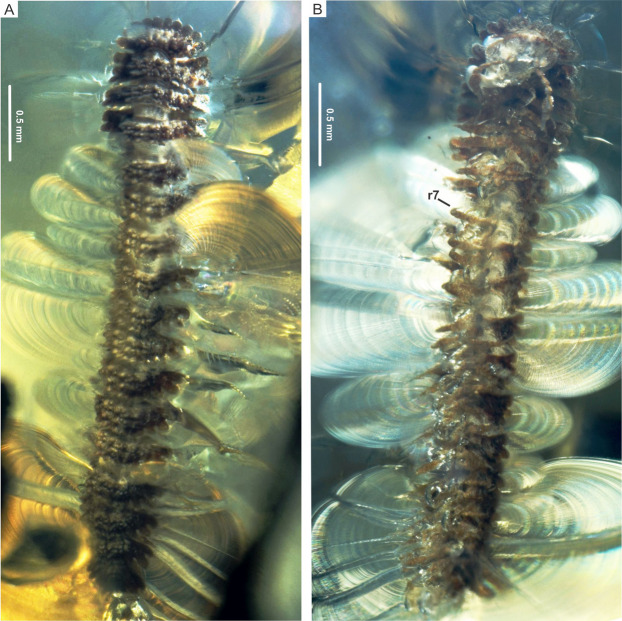

Figure 1. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov.

Holotype CPAL.132, amber inclusion, complete fossil specimen, male adult. (A) Dorsal view. (B) Ventral view, showing ring 7. Abbreviation: r, body ring.

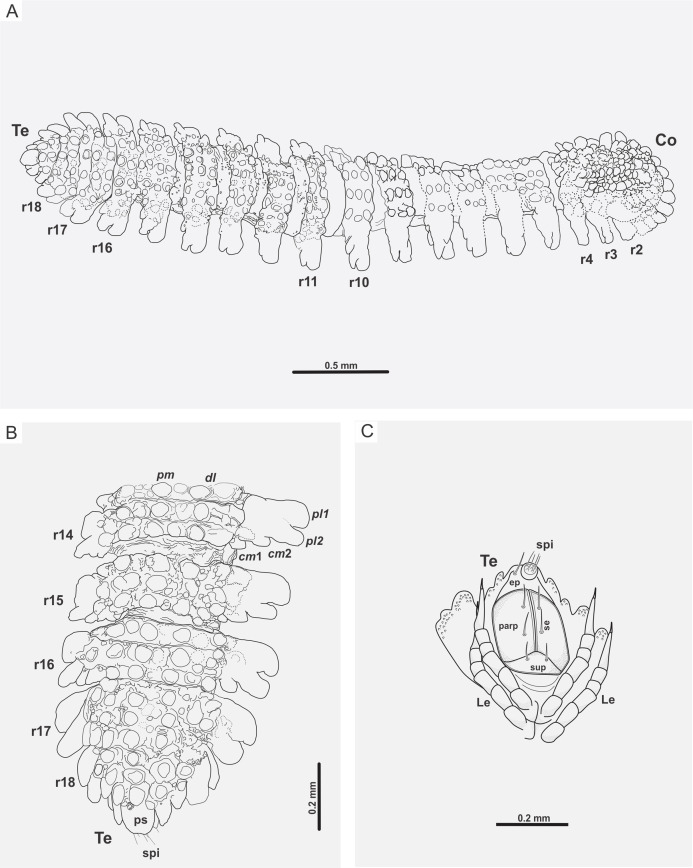

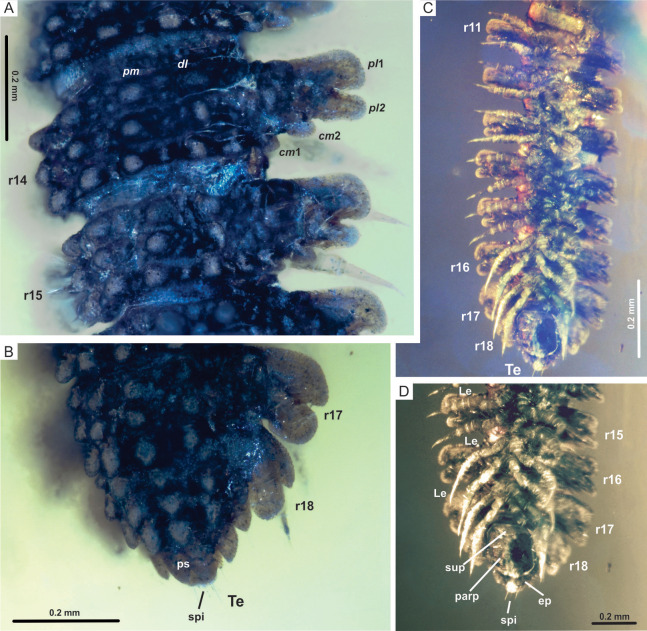

Figure 5. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov.

(A) CPAL.117, line drawing of the complete fossil specimen, dorsal view, showing collum, trunk, and telson. (B) CPAL.117, schematic reconstruction of posterior end, dorsal view, showing rings 14–18, and telson. (C) CPAL.117, schematic reconstruction of telson, ventral view, showing subanal plate, paraprocts, epiproct, spinnerets, setae, and associated legs in posterior end. Abbreviations: cm, caudomarginal lobe; Co, collum; dl, dorsolateral tubercle; ep, epiproct; Le, leg; parp, paraprocts; pl, paranotal lobe; pm, paramedian tubercle; ps, preanal sclerite; r, body ring; se, setae; spi, spinneret; sup, subanal plate; Te, telson.

ZooBank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:EA1B5DD9-14AC-46DB-9D00-3D699F84C296

Etymology. From the Latin word “antiquus” (m.), which means “ancient”. It alludes to the fossil condition of the specimens.

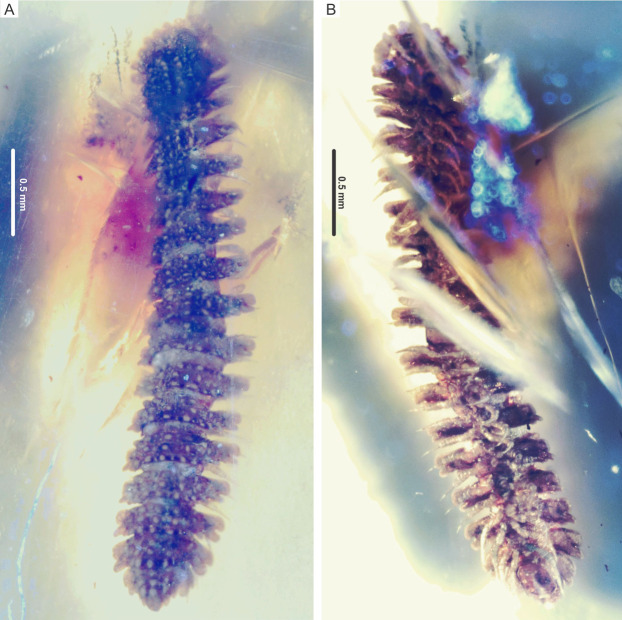

Type material. Holotype CPAL.132 (Fig. 1), amber inclusion, entire specimen, male adult with 19 rings, housed at the CPAL-UAEM (2019). Paratype CPAL.117 (Fig. 2), amber inclusion, entire specimen, female adult with 19 rings, housed at the CPAL-UAEM (2017).

Figure 2. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov.

Paratype CPAL.117, amber inclusion, complete fossil specimen, female adult. (A) Dorsal view. (B) Ventral view.

Locality and Horizon. Los Pocitos site, Simojovel, Chiapas, Mexico, latitude 17° 08′ 32″ N, longitude 92° 43′ 27″ W. The amber-bearing rocks belong to Mazantic shale and Balumtum sandstone strata dated as early-middle Miocene, ca. 23–15 Ma (Poinar, 1992; Perriliat, Vega & Coutiño, 2010; Riquelme et al., 2013).

Diagnosis. With traits of the genus Myrmecodesmus sensu Shear (1977), plus the following combination of diagnostic characters: collum with 10 dorsal tubercles; without porosteles or ozopores; legs of the rings 2–9 with a short projection on the prefemur in both female and male.

Description. Color preserved in amber, brownish-gray from the dorsal view, and pale gray in ventral view. Holotype CPAL.132, male, complete specimen (Fig. 1). Paratype CPAL.117, female, complete specimen (Fig. 2). Measurements (in mm): CPAL.132: head plus 19 rings, length 3.7, collum width 0.6, metazonite width 0.72, prozonite width 3.0. CPAL.117: head plus 19 rings, length 3.3, collum width 0.57, metazonite 0.68, prozonite width 0.28 (Figs. 1 and 2).

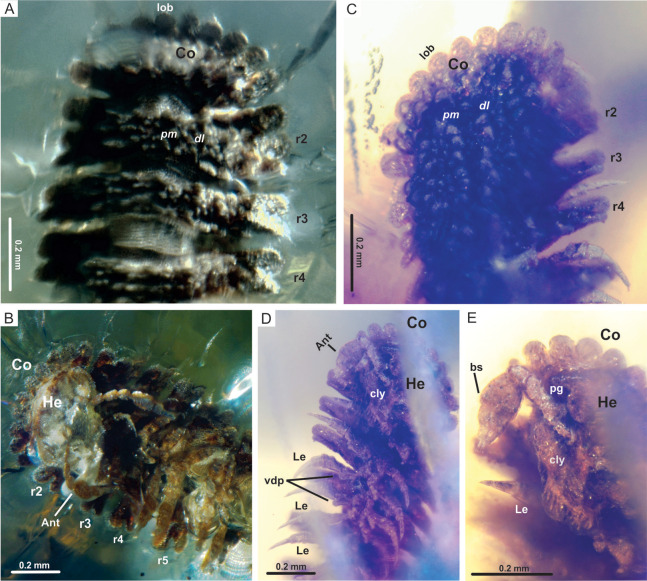

Head: vertex and frons roughened, partially sunk, slightly granular surface, clypeus also granular, with 10–12 setae (Figs. 1B, 2B, 3B and 3D)

Figure 3. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov.

(A) CPAL.132, male, dorsal view of anterior end, showing collum and rings 2–4. (B) CPAL.132, ventral view of anterior end, showing head, antenna, collum lobes, and rings 2–5. (C) CPAL.117, female, dorsal view of anterior end, showing collum and rings 2–4. In both specimens: collum with 10 lobes and rings 2–4 with two paramedian and two dorsolateral tubercle rows. (D) CPAL.117, ventral view of anterior end, showing head, antenna, rings 2–6, and associated legs with ventrodistal projection on the prefemur. (E) CPAL.117, closer view at the head and antenna with bacilliform sensilla. Abbreviations: Ant, antenna; bs, bacilliform sensilla; cly, clypeus; Co, collum; dl, dorsolateral tubercle; He, head; Le, leg; lob, lobe; pm, paramedian tubercle; pg, postantennal groove; r, body ring; vdp, ventrodistal projection.

Antenna: consisting of 7 antennomeres; postantennal groove deep; antennal sockets separated by ca 1× the socket diameter; antennae short, stout and clavate. The antennomere are widest in the female CPAL.117. Antennomere 5 widest. Antennomere relative widths 5 > 6 > 7 > (4 = 3 =2 = 1), relative lengths (3 = 5) >2 > 6 > 4 > 7 > 1 and four apical, long, and slender sensory cones. Distinctly tight group of bacilliform sensilla on the apical, retrolateral edge of antennomere 5 (Figs. 3B, 3D and 3E).

Trunk: collum flabellate covering head in dorsal view; anterior margin divided into 10 equal rounded lobes separated and parallel to ground; dorsal surface domed with 2 transverse rows of tubercles, posterior row with 4 large tubercles, medial row with 6 medium tubercles, the rest of the collum surface with small tubercles (Figs. 3A and 3C). Midbody metazonite surface with 4 longitudinal rows of 2 paramedian (pm) and 2 dorsolateral (dl) tubercles, composed of 3 large tubercles that are basally fused; a group of 4 or 6 small tubercles intercalate between dl and pm tubercles, and 2 rows of 5 or 6 small tubercles middorsally, a variable number of medium and small tubercles between dl tubercles and paranota; collum, tergites and metazonites lacking setae. Prozonites slightly granular, some margins with tiny tubercle-like cuticular outgrowths (Figs. 4A, 4B and 5A). Paranota medium-sized, arising low on body, slightly directed anteriorly, declined, anterior margin straight, undivided, pitched slightly so anterior margin is lower than posterior margin. Ring 2 paranotum expanded anterodistally, lateral margin weakly divided with typical 3 rounded lateral paranota lobes (pl); pl1, pl2 and pl3 are sub-equal, lacking caudomarginal (cm) and anteriormarginal (am) lobes (Figs. 3A and 3C). Ring widths 3–16 about equal, gradually decreasing on rings 17–18 (Figs.1, 2, 3, 4 and 5A). Paranota of rings 3–18, with anterior margin straight, undivided; 2 strong pl; posterior margin with two caudomarginal lobes, cm1 shorter than cm2. Paranota of rings 17–18 directed posterolaterally, ring 17 with one cm, and ring 18 without cm. Ozopores not visible, without porosteles (Figs.1A, 2B, 4A, 4B, 5A and 5B).

Figure 4. Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov.

(A) CPAL.117, dorsal view of rings 14 and 15, showing paramedian and dorsolateral tubercles, and paranota with two caudomarginal and two paranotal lobes. (B) CPAL.117, dorsolateral view of posterior end, showing rings 16–18, and telson. (C) CPAL.117, ventral view of midbody rings and posterior end, showing rings 11–18, and telson. (D) CPAL.117, closer view at the posterior end, ventral view, showing subanal plate, paraprocts, epiproct, and spinnerets. Abbreviations: cm, caudomarginal lobe; dl, dorsolateral tubercle; ep, epiproct; Le, leg; parp, paraprocts; pl, paranotal lobe; pm, paramedian tubercle; ps, preanal sclerite; r, body ring; spi, spinneret; sup, subanal plate; Te, telson.

Legs: subequal, short and slender, hidden by paranota in dorsal view; relative podomere lengths tarsus>femur>prefemur>(postfemur = tibia)>coxa and with a long claw. Legs with modified prefemur in rings 2–9, with a short ventrodistal projection protruding. Spiracles not evident (Figs. 3B, 3D, 4C and 4D).

Telson: preanal sclerite with 3+3 lateral lobes and 2 small dorsal tubercles; epiproct not hidden under 18th segment, short, bluntly rounded, with 4 strong spinnerets in square array below apex; anal valves each with 2 setae near the mesal margin; subanal plate rounded-triangular with 2 setae near the apex. Sternites slightly roughened, not setose, wider than long; coxae nearly contiguous, with a transverse impression slightly deeper than longitudinal (Figs. 4C, 4D, 5B and 5C).

Remarks. Gonopods are not visible in the male CPAL.132 and the epigyne and cyphopods are also not distinguishable in the female CPAL.117, as a consequence of the state of conservation of the bodies and because they are partially covered with cloudy amber. However, CPAL.132 and CPAL.117 are interpreted as male and female adults, respectably, due to the number of rings =19 (extant species of Myrmecodesmus may have either 19 or 20 rings as adults), the paranota and metazonite tubercles strongly differentiated, as well as the number of legs in ring 7 of the male (Figs. 1B, 2B and 3B–3D).

Discussion

Unresolved taxonomic issues persist in the genus Myrmecodesmus (Shear, 1973; Shelley, 2002; Recuero, 2014). A large number of the currently valid species show partial taxonomic descriptions and there is no key or consensus on the diagnostic characters in the genus. This leads to certain uncertainties in the species diagnosis. The synapomorphies of the group also seems ambiguous. At present, it is an unsolved problem in Diplopoda taxonomy (Shear, 1973, 1977; Hoffman, 1980; Hoffman et al., 1996; Adis, 2002; Golovatch & VandenSpiegel, 2014; Recuero, 2014). Myrmecodesmus is a diverse genus with some of the highest species numbers that exist within the family Pyrgodesmidae (Golovatch, 1999; Golovatch & Adis, 2004; Shelley, 2004; Golovatch et al., 2016). Table 1 shows an updated list of the valid species that belong to Myrmecodesmus, according to the literature reviewed to date. It is a group that currently comprises 36 described extant species (Shear, 1977; Reddell, 1981; Golovatch, 1999; Hoffman, 1999; Shelley, 2004; Recuero, 2014). Accordingly, M. antiquus sp. nov. is the only fossil species described in the genus so far.

Table 1. The current list of species in the genus Myrmecodesmus Silvestri, 1910 (Diplopoda: Polydesmida: Pyrgodesmidae), including the fossil Myrmecodesmus antiquus sp. nov.

| Species | Distribuction | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myrmecodesmus aconus Shear, 1973 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 2 | Myrmecodesmus adisi Hoffman, 1985 | Brazil | Golovatch (1999) | |

| 3 | Myrmecodesmus amarus Causey, 1971 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 4 | Myrmecodesmus amplus Causey, 1973 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 5 | Myrmecodesmus analogous Causey, 1971 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 6 | †Myrmecodesmus antiquus Riquelme & Hernández-Patricio, 2021 | Miocene, Mexico | Riquelme et al. (2021) | |

| 7 | Myrmecodesmus atopus Chamberlin, 1943 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 8 | Myrmecodesmus brevis Shear, 1977 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 9 | Myrmecodesmus chamberlini Shear, 1977 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 10 | Myrmecodesmus chipinqueus Chamberlin, 1943 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 11 | Myrmecodesmus clarus Chamberlin, 1942 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 12 | Myrmecodesmus cornutus Shear, 1973 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 13 | Myrmecodesmus digitatus Loomis, 1959 | USA | Hoffman (1999) | |

| 14 | Myrmecodesmus duodecimlobatus Golovatch, 1996 | Brazil | Golovatch (1999) | |

| 15 | Myrmecodesmus egenus Causey, 1971 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 16 | Myrmecodesmus errabundus Shear, 1973 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 17 | Myrmecodesmus fissus Causey, 1977 | Mexico | Reddell (1981) | |

| 18 | Myrmecodesmus formicarius Silvestri, 1910 | Mexico | Shelley (2004) | |

| 19 | Myrmecodesmus fractus Chamberlin, 1943 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 20 | Myrmecodesmus fuscus Causey, 1977 | Mexico | Reddell (1981) | |

| 21 | Myrmecodesmus gelidus Causey, 1971 | Mexico | Hoffman (1999) | |

| 22 | Myrmecodesmus hastatus Schubart, 1945 | Brazil, Peru, Argentina, Martinique, Lesser Antilles | Golovatch & Adis (2004) | |

| 23 | Myrmecodesmus ilymoides Shear, 1973 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 24 | Myrmecodesmus inornatus Shear, 1977 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 25 | Myrmecodesmus margo Causey, 1977 | Mexico | Causey (1977) | |

| 26 | Myrmecodesmus minusculus Golovatch, 1996 | Brazil | Golovatch (1999) | |

| 27 | Myrmecodesmus modestus Silvestri, 1911 | Mexico | Silvestri (1911) | |

| 28 | Myrmecodesmus monasticus Causey, 1971 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 29 | Myrmecodesmus morelus Chamberlin, 1943 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 30 | Myrmecodesmus mundus Chamberlin, 1943 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 31 | Myrmecodesmus obscurus Causey, 1971 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 32 | Myrmecodesmus orizaba Chamberlin, 1941 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 33 | Myrmecodesmus potosinus Chamberlin, 1943 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 34 | Myrmecodesmus reddelli Shelley, 2004 | USA | Shelley (2004) | |

| 35 | Myrmecodesmus sabinus Chamberlin, 1942 | Mexico | Shear (1977) | |

| 36 | Myrmecodesmus sheari Recuero, 2014 | Mexico | Recuero (2014) | |

| 37 | Myrmecodesmus unicorn Shear, 1977 | Belize | Shear (1977) |

Among the Polydesmida, the family Pyrgodesmidae shows a Pantropical distribution, which includes southern USA, Mexico, Central America, the Antilles, South America, South Europe, Africa, Asia, India and Oceania (Hoffman, 1980, 1999; Golovatch, 1996; Shelley & Golovatch, 2001; Golovatch & Kime, 2009; Jorgensen & Sierwald, 2010; Mesibov, 2012; Enghoff et al., 2015). The living members of the Pyrgodesmidae count 371 nominal species included in 170 genera, most of them monotypes (Jorgensen & Sierwald, 2010; Enghoff et al., 2015). For its part, the genus Myrmecodesmus is an exclusively New World taxon, and the extant species of Myrmecodesmus are distributed in USA, Mexico, Belize, the Antilles, Peru, Brazil and Argentina (Golovatch, 1999; Hoffman, 1999; Bueno-Villegas, Sierwald & Bond, 2004; Golovatch & Adis, 2004; Bergholz, Adis & Golovatch, 2004; Shelley, 2004; Golovatch et al., 2016). Most species have been described from Mexico, and the genus has a current distribution in the Nearctic and Neotropical regions (Table 1). Originally, Myrmecodesmus was erected by Silvestri, 1910 to group some related morphotypes found in Veracruz, southern Mexico (Recuero, 2014). Thus, the occurrence of M. antiquus sp. nov. expands the range of the genus to the Miocene tropics in Middle America.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susana Guzmán at the IBUNAM for helping to take photomicrographs and Derek Hennen at Virgina Tech for English editing. We thank the Academic editor Jason Bond, as well as William Shear and one other anonymous reviewer, whose comments and suggestions have improved the final published version of this article.

Funding Statement

The authors received no funding for this work.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author Contributions

Francisco Riquelme conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Miguel Hernández-Patricio conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, and approved the final draft.

Michelle Álvarez-Rodríguez analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, and approved the final draft.

Data Availability

New Species Registration

The following information was supplied regarding the registration of a newly described species:

Publication LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:95759D56-205C-4FD2-A01B-0CE3F9621E0E.

Myrmecodesmus antiquus LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:EA1B5DD9-14AC-46DB-9D00-3D699F84C296.

References

- Adis (2002).Adis J. Amazonian arachnida and myriapoda: identification keys to all classes, orders, families, some genera, and lists of known terrestrial species. Sofia: Pensoft; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bergholz, Adis & Golovatch (2004).Bergholz NGR, Adis J, Golovatch SI. New records of the millipede Myrmecodesmus hastatus (Schubart, 1945) in Amazonia of Brazil (Diplopoda: Polydesmida: Pyrgodesmidae) Amazoniana: Limnologia Et Oecologia Regionalis Systemae Fluminis Amazonas. 2004;1(2):157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Villegas, Sierwald & Bond (2004).Bueno-Villegas J, Sierwald P, Bond JE. Diplopoda. In: Llorente Bousquets J, Morrone JJ, Yáñez O, Vargas I, editors. Biodiversidad, Taxonomía y Biogeografía de Artrópodos de México: Hacia una Síntesis de su Conocimiento. IV. UNAM: México; 2004. pp. 569–599. [Google Scholar]

- Causey (1977).Causey NB. Millipedes in the collection of the Association for Mexican Cave Studies—IV: new records and descriptions chiefly from the northern Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico (Diplopoda) Bulletin Association for Mexican Cave Studies Bulletin. 1977;6:167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cook (1896a).Cook OF. On recent diplopod names. Brandtia. 1896a;2:5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cook (1896b).Cook OF. Cryptodesmus and its allies. Brandtia. 1896b;5:19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cook (1911).Cook OF. Notes on the distribution of millipeds in Southern Texas, with descriptions of new genera and species from Texas, Arizona, Mexico and Costa Rica. Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 1911;40:147–167. [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Ruíz et al. (2013).Durán-Ruíz C, Riquelme F, Coutiño-José M, Carbot-Chanona G, Castaño-Meneses G, Ramos-Arias M. Ants from the Miocene Totolapa amber (Chiapas, Mexico), with the first record of the genus Forelius (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 2013;50(5):495–502. doi: 10.1139/cjes-2012-0166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enghoff et al. (2015).Enghoff H, Golovatch SI, Short M, Stoev P, Wesener T. Diplopoda—taxonomic overview. In: Minelli A, editor. Treatise on Zoology—Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology: The Myriapoda. Vol. 2. Netherlands: Brill; 2015. pp. 363–453. [Google Scholar]

- Golovatch (1996).Golovatch SI. Two new and one little-known species of the millipede family Pyrgodesmidae from near Manaus, Central Amazonia, Brazil (Diplopoda: Polydesmida) Amazoniana: Limnologia Et Oecologia Regionalis Systemae Fluminis Amazonas. 1996;14(1–2):109–120. [Google Scholar]

- Golovatch (1999).Golovatch SI. On six new and some older Pyrgodesmidae from the environs of Manaus, Central Amazonia, Brazil (Diplopoda, Polydesmida) Amazoniana: Limnologia Et Oecologia Regionalis Systemae Fluminis Amazonas. 1999;15:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Golovatch & Adis (2004).Golovatch SI, Adis J. Myrmecodesmus hastatus (Schubart, 1945), a widespread Neotropical millipede (Diplopoda, Polydesmida, Pyrgodesmidae) Fragmenta Faunistica. 2004;47(1):35–38. doi: 10.3161/00159301FF2004.47.1.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Golovatch et al. (2016).Golovatch SI, Geoffroy JJ, Mauriès JP, VandenSpiegel D. Detailed iconography of the widespread Neotropical millipede, Myrmecodesmus hastatus (Schubart, 1945), and the first record of the species from the Caribbean area (Diplopoda, Polydesmida, Pyrgodesmidae) Fragmenta Faunistica. 2016;59(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Golovatch & Kime (2009).Golovatch SI, Kime RD. Millipede (Diplopoda) distributions: a review. Soil Organisms. 2009;81(3):565–597. [Google Scholar]

- Golovatch & VandenSpiegel (2014).Golovatch SI, VandenSpiegel D. Notes on Afrotropical Pyrgodesmidae, 1 (Diplopoda: Polydesmida) Arthropoda Selecta. 2014;23(4):319–335. doi: 10.15298/arthsel.23.4.01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham (1999).Graham A. Studies in Neotropical Paleobotany—XIII: an Oligo-Miocene palynoflora from Simojovel (Chiapas, Mexico) American Journal of Botany. 1999;86(1):17–31. doi: 10.2307/2656951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman (1976).Hoffman RL. A new lophodesmid milliped from a Guatemalan cave, with notes on related forms (Polydesmida: Pyrgodesmidae) Revue Suisse de Zoologie. 1976;83(2):307–316. doi: 10.5962/bhl.part.91432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman (1980).Hoffman RL. Classification of the diplopoda. Genève: Museum d’Histoire Naturelle; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman (1999).Hoffman RL. Checklist of the millipeds of North and Middle America. Virginia: Virginia Museum of Natural History; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman et al. (1996).Hoffman RL, Golovatch SI, Adis J, De Morais JW. Practical keys to the orders and families of millipedes of the Neotropical region (Myriapoda: Diplopoda) Amazoniana: Limnologia Et Oecologia Regionalis Systemae Fluminis Amazonas. 1996;14(1/2):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen & Sierwald (2010).Jorgensen M, Sierwald P. Review of the Caribbean pyrgodesmid genus Docodesmus Cook with notes on potentially related genera (Diplopoda, Polydesmida, Pyrgodesmidae) International Journal of Myriapodology. 2010;3(1):25–50. doi: 10.1163/187525410X12578602960461. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koch (2015).Koch M. Diplopoda—general morphology. In: Minelli A, editor. Treatise on Zoology—Anatomy, Taxonomy, Biology: The Myriapoda. Vol. 2. Netherlands: Brill; 2015. pp. 7–67. [Google Scholar]

- Langenheim (1966).Langenheim JH. Botanical source of amber from Chiapas, Mexico. Ciencia. 1966;24:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Langenheim (2003).Langenheim JH. Plant resins: chemistry, evolution, ecology and ethnobotany. Portland: Timber Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mesibov (2012).Mesibov R. The first native Pyrgodesmidae (Diplopoda, Polydesmida) from Australia. ZooKeys. 2012;217(2):63–85. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.217.3809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perriliat, Vega & Coutiño (2010).Perriliat MC, Vega FJ, Coutiño MA. Miocene mollusks from the Simojovel area in Chiapas, Southwestern Mexico. Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 2010;30(2):111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jsames.2010.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock (1894).Pocock RI. Chilopoda, symphyla and diplopoda from the Malay Archipelago. In: Weber M, editor. Zoologische Ergebnisse einer Reise in Niederländisch Ost-Indien. Leiden: Band 3; 1894. pp. 307–404. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar (1992).Poinar GO. Life in amber. Palo Alto: Standford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Recuero (2014).Recuero E. A new name for Myrmecodesmus potosinus (Shear) 1973, a homonym of Myrmecodesmus potosinus (Chamberlin) 1943 (Diplopoda, Polydesmida, Pyrgodesmidae) Zootaxa. 2014;3869(5):594–596. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3869.5.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddell (1981).Reddell JR. A review of the cavernicole fauna of Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize. Vol. 27. Austin: Bulletin of the Texas Memorial Museum; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme et al. (2013).Riquelme F, Alvarado-Ortega J, Ramos-Arias M, Hernández M, Le Dez I, LeeWhiting TA, Ruvalcaba-Sil JL. A fossil stemmiulid millipede (Diplopoda: Stemmiulida) from the Miocene amber of Simojovel, Chiapas, Mexico. Historical Biology. 2013;26(4):415–427. doi: 10.1080/08912963.2013.778843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme & Hernández-Patricio (2018).Riquelme F, Hernández-Patricio M. The millipedes and centipedes of Chiapas amber. Check List. 2018;14(4):637–646. doi: 10.15560/14.4.637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme et al. (2014a).Riquelme F, Hernández-Patricio M, Martínez-Dávalos A, Rodríguez-Villafuerte M, Montejo-Cruz M, Alvarado-Ortega J, Ruvalcaba-Sil JL, Zúñiga-Mijangos L. Two flat-backed Polydesmidan Millipedes from the Miocene Chiapas-amber Lagerstätte, Mexico. PLOS ONE. 2014a;9(8):e105877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riquelme et al. (2014b).Riquelme F, Northrup P, Ruvalcaba-Sil JL, Stojanoff V, Siddons DP, Alvarado-Ortega J. Insights into molecular chemistry of Chiapas amber using infrared-light microscopy, PIXE/RBS, and sulfur K-edge XANES spectroscopy. Applied Physics A. 2014b;116(1):97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00339-013-8185-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf (2013).Rohlf FJ. The tpsDig program, V. 2.17. New York: Stony Brook University; 2013. pp. 2–17. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Blay & Poinar (1992).Santiago-Blay JA, Poinar GO. Millipeds from Dominican Amber, with the description of two new species (Diplopoda: Siphonophoridae) of Siphonophora. Annals of the Entomological Society of America. 1992;85(4):363–369. doi: 10.1093/aesa/85.4.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shear (1973).Shear WA. Millipeds (Diplopoda) from Mexican and Guatemalan caves. Accademia, Nazionale dei Lincei, Problemi Attuali di Scienza e di Cultura. 1973;171(2):240–305. [Google Scholar]

- Shear (1977).Shear WA. Millipeds (Diplopoda) from Caves in Mexico, Belize and Guatemala—III. Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Problemi Attuali di Scienza e di Cultura. 1977;171:235–265. [Google Scholar]

- Shear (1981).Shear WA. Two fossil millipeds from the Dominican amber (Diplopoda: Chytodesmidae, Siphonophoridae) Myriapodologica. 1981;1:51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shear (2011).Shear WA. Class diplopoda de Blainville in Gervais, 1844—In: Zhang, ZQ, ed. Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa. 2011;3148:159–164. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.3148.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley (2002).Shelley RM. Redescription of the milliped Myrmecodesmus mundus (Chamberlin) (Polydesmida: Pyrgodesmidae) Zootaxa. 2002;115(1):1–6. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.115.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley (2004).Shelley RM. The milliped family Pyrgodesmidae in the continental USA, with the first record of Poratia digitata (Porat) from the Bahamas (Diplopoda: Polydesmida) Journal of Natural History. 2004;38(9):1159–1181. doi: 10.1080/0022293031000071550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley & Golovatch (2001).Shelley RM, Golovatch SI. New records of the milliped family pyrgodesmidae (Polydesmida) from the southeastern United States, with a summary of the Fauna. Entomological News. 2001;112(1):59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri (1911).Silvestri F. Contributo alla conoscenza ei Mirmecofili del Messico: Diplopoda-Polydesmoidea. Bollettino del Laboratorio di Zoologia Generale e Agraria della Reale Scuola Superiore d’ Agricoltura in Portici. 1911;5:190–195. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The material is deposited at the Colección de Paleontología, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos (CPAL-UAEM): Code numbers: CPAL.117, CPAL.132.