Abstract

This case is being reported to draw the attention of non-cardiac practicing physicians including pulmonologists, intensivists, and, as a matter of fact all primary care and emergency clinicians, towards a relatively uncommon ECG finding that could be the potential lead in suspecting the diagnosis of a commonly encountered, often fatal medical condition. Together with a high clinical index of suspicion, this alone could guide the decision-making process for further work-up and specific therapy.

Keywords: ECG, pulmonary embolism, S1Q3T3 pattern

Case Summary

A 40-year-old female presented with complaints of streaky cough, shortness of breath [Medical Research Council (MRC) – grade 1] and fever for the last 7 days. Upfront abnormalities on initial evaluation included a left lower zone consolidation on chest radiograph, neutrophilic leukocytosis, elevated procalcitonin, mildly deranged renal functions, and hypotension which responded to fluid resuscitation and minimal vasopressor support. She was admitted with a provisional clinical diagnosis of left lower lobe pneumonia with septic shock and acute kidney injury, and treatment initiated on those lines as per standard protocol.

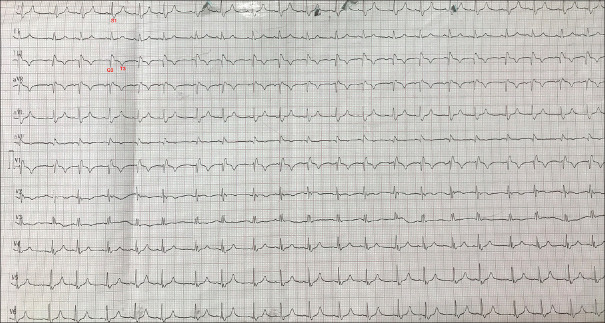

One day into her hospitalization in the respiratory intensive care unit, she developed sudden worsening of breathlessness (MRC-grade 4), associated with hypotension, tachypnoea, tachycardia and hypoxemia. Chest auscultation revealed bilaterally equal normal vesicular breath sounds with few crackles at the left lung base. There was no bronchospasm. Repeat chest radiograph was equivocal. An urgent ECG was performed [Figure 1], and immediately followed by bedside transthoracic echocardiography which showed massively enlarged right atrium and right ventricle, with septal deviation towards the left, and D-shaped left ventricle.

Figure 1.

Patient's ECG

Questions

What is the classic abnormality depicted in the ECG?

What is the likely diagnosis?

Answers

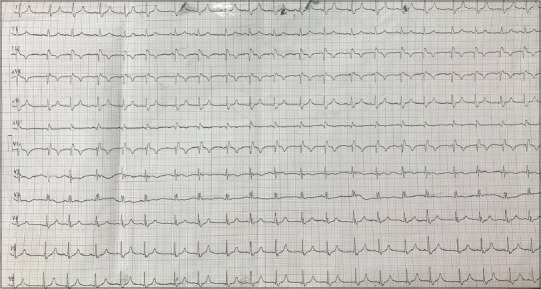

The ECG shows a classical S1Q3T3 pattern [Figure 2]. Additional findings include sinus tachycardia, a right bundle branch block (which was of new onset), and inverted T waves in leads III, aVF, and V1-V3. These abnormalities indicate right ventricular strain.

The acute clinical worsening and compatible ECG and echocardiographic findings indicate towards development of an acute massive pulmonary embolism (PE).

Figure 2.

ECG of the patient showing classical S1Q3T3 pattern (see text for description)

Discussion

The S1Q3T3 pattern, also called the S1Q3 pattern, was first described by McGinn and White in 1935.[1] Literature published since then has described this finding in classical association with right heart strain seen in acute cor pulmonale, commonly associated with acute PE. This suggests that in the relevant clinical setting, presence of S1Q3T3 can be useful to raise an early suspicion of this potentially life-threatening medical emergency.[2,3,4] Incidence of S1Q3T3 is between 10-50% in acute PE but is non-specific and, importantly, can be seen in other conditions like acute bronchospasm, pneumothorax, other acute lung disorders causing acute cor pulmonale.[5] In the present case, these differentials were excluded by bedside clinico-radiological examination. The pattern carries an approximate sensitivity of 50% for PE diagnosis.[6] It is characterized by a prominent S wave in lead I, and Q wave and an inverted T wave in lead III [Figure 2]. It is usually transient and resolves within two weeks of PE.[7]

In our case, the sudden clinical worsening together with suggestive ECG abnormalities, echocardiographic findings, and presence of lower limb deep vein thrombosis which was detected on further evaluation by color Doppler, indicated towards development of anacute massive PE. The patient was thrombolysed and further work-up was planned to look for any prothrombotic states, but she rapidly succumbed to her deteriorating clinical condition.

The case is being reported to increase awareness among primary care physicians who may often encounter similar clinical scenarios, wherein patients present with acute breathlessness with accompanying tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypoxemia and/or hypotension. In the primary care and emergency setting, baseline ECG is routinely performed as part of the initial diagnostic evaluation of such patients. Identification of S1Q3T3 pattern with or without other ECG abnormalities [8] as described above, can be utilized as a simple, immediate, bedside and cost-effective method to trigger an early suspicion of acute PE in the correct clinical setting. As quite a few patients, especially the elderly, bed-ridden, and the ones admitted to the intensive care unit, may have prothrombotic states (like malignancy, deep vein thrombosis, etc.) that could potentially lead to development of PE, it is crucial to spot this ECG finding to guide and expedite further management decisions, or, in resource-limited settings, decide upon timely referral to a specialist center. It may prove even more useful in situations where confirmatory imaging tests for PE may not be immediately feasible due to urgency of the clinical scenario, patient's clinical instability and/or presence of contraindications, or logistic constraints of the health care setting. In such cases, it may prompt toward performance of a rapid bedside echocardiogram to look for changes that further support a PE diagnosis, and thus guide critical decision making to initiate definitive therapy as soon as possible.[9]

To conclude, the present report highlights the fact that although the S1Q3T3 pattern is non-specific and has a moderate sensitivity for diagnosis of PE, its presence on the ECG in a compatible clinical background must alert the treating physician towards the possibility of this potentially catastrophic condition.

Patient consent

Informed verbal consent was taken from the patient's attendant.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.McGinn S, White PD. Acute cor pulmonale resulting from pulmonary embolism. JAMA. 1935;104:1473–80. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari E, Imbert A, Chevalier T, Mihoubi A, Morand P, Baudouy M. The ECG in pulmonary embolism. Predictive value of negative T waves in precordial leads – 80 case reports. Chest. 1997;111:537–43. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.3.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahani L. S1Q3T3 pattern leading to early diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:pii:bcr2012006569. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-006569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shopp JD, Stewart LK, Emmett TW, Kline JA. Findings from 12-lead electrocardiography that predict circulatory shock from pulmonary embolism: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22:1127–37. doi: 10.1111/acem.12769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ali OM, Masood AM, Siddiqui F. Bedside cardiac testing in acute cor pulmonale. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:pii:bcr2013200940. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ullman E, Brady WJ, Perron AD, Chan T, Mattu A. Electrocardiographic manifestations of pulmonary embolism. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:514–9. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2001.27172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen TT, Lund O, Ronne K, Schifter S. Changing electrocardiographic findings in pulmonary embolism in relation to vascular obstruction. Cardiology. 1989;76:274–84. doi: 10.1159/000174504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boey E, Teo SG, Poh KK. Electrocardiographic findings in pulmonary embolism. Singapore Med J. 2015;56:533–7. doi: 10.11622/smedj.2015147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sullivan AE, Holder T, Patel MR, Fortin T, Jones WS. Electrocardiographic characteristics in a large cohort of acute pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(Suppl 1) doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(20)32899-0. [Google Scholar]