Abstract

Context:

Epilepsy is said to be intractable when two or more trials of anticonvulsants fail to control the seizures. Literature suggests that intractable epilepsy carries a higher morbidity than controlled epilepsy in children and their caregivers.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to assess the quality of life (QOL) in children with intractable epilepsy (IE) in KASCH, a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Settings and Design:

This is a cross-sectional study utilizing a self-administered questionnaire filled by caregivers of epileptic patients visiting the outpatient neurology clinics.

Methods and Materials:

The quality of life in childhood epilepsy (QOLCE-55) scale examined four domains of life: cognitive, emotional, social, and physical. The sample consisted of 59 parents whose children aged 4-14 of either sex.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The collected data were analyzed by Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.

Results:

The mean age of children was 8.9 (SD = 2.9). The mean QOL was 52.8 (SD = 12.9), which reflected a poor QOL. Age was not related to the QOL. Gender was significantly associated with the total and social scores, (P = 0.04) (P = 0.001), respectively. Out of all comorbidities, global developmental delay (GDD) and encephalopathy were significantly associated with the QOL (P < 0.05).

Conclusions:

Intractable epilepsy impacted all functioning domains of life rendering a poor QOL. Males have reported better QOL and social functioning compared to females. Children with GDD and encephalopathy showed lower well-being.

Keywords: Epilepsy, intractable, pediatric, quality of life

Introduction

Epilepsy is a neurological disease characterized by two or more unprovoked seizures. It is an abnormal electrical firing of neurons.[1] Depending on which part of the cortex the excessive electrical discharge affects, seizures are divided into two types. One type is focal seizures, which affect only one cerebral hemisphere. Focal seizures can be further classified depending on the presence of aura, motor features, and awareness or responsiveness.[1] Generalized seizures, on the other hand, affect both cerebral hemispheres, and are always accompanied by loss of consciousness.[1] Some seizures originate in one hemisphere then gradually spread to the whole cortex; in this case they are called secondary generalized seizures.[1] It is important to highlight that a single seizure is not necessarily indicative of epilepsy.[2] Seizures could be provoked by other factors such as sleep deprivation, alcohol withdrawal, medications, and infections. Ten percent of the world's population will have at least one seizure, and one- third of whom will develop epilepsy.[3] The incidence of epilepsy is age-dependent. It most commonly starts at childhood or after the age of 60, while middle-aged people are less likely to develop epilepsy.[1,4,5] Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder where every year 50 − 70 cases in 100,000 population are reported.[4,5] In around 70% of cases, epileptic seizures are controlled on antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Intractable epilepsy is defined as the failure of two or more AEDs trials, provided that optimal doses and the right choice of AED are achieved.[6] Depending on the way of development into intractable epilepsy, drug resistance can be categorized into de novo, progressive, and waxing and waning.[6] De novo is when the drug resistance occurs before any AEDs were given. Progressive drug resistance is when epilepsy used to be but no longer controlled by AEDs. The waxing and waning is the state of interchanging between drug responsiveness and resistance.[6]

After the failure of one appropriate trial, only 11% of patients become seizure-free, while 3% become seizure-free after the failure of the second appropriate trial.[7] Studies have shown that the quality of life (QOL) in patients with intractable epilepsy is less optimistic than in those with controlled epilepsy.[8] In countries where sufficient diagnosis and treatment are obtainable, 30-40% of patients with epilepsy have seizures that cannot be controlled with medications.[9] A study conducted in Canada to assess the QOL in pediatrics with intractable epilepsy showed the negative impact on physical, emotional, cognitive, and social aspects of life.[10] Physically, the major complaint was persistent fatigue and need for sleep. Emotionally, anger and frustration scored higher (67%) than fear (49%) and depression (45%). Cognitively, 70% reported memory and learning problems, and social isolation was highly reported.[10] Another study conducted in Sudan in 2011 also measured the QOL in pediatrics and their caregivers.[11] Results showed a significant low QOL in both the pediatrics and their caregivers. The study reflected the caregivers’ commonest concerns. Socially, it was the increased supervision that their children needed compared to other children. Physically, it was self-harm and psychologically, it was the moodiness.[11] Locally, a study was conducted in three hospitals in Jeddah to assess the impact of epilepsy on children.[12] The cause of seizure, monthly income, and child's nationality were significantly associated with QOL. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) and cerebral palsy (CP) were strongly linked with lower QOL. More than 94% of families earning <5000 SAR a month reported lower QOL. Furthermore, non-Saudi children compared to Saudis had lower QOL.[12]

Epilepsy has a significant impact on the everyday life of affected individuals.[13] This mandates a multidisciplinary team utilizing all levels of care. Primary care physicians can help improve the QOL by offering continuous counseling to the patients and their parents, find out their expectations and concerns, assess treatment adherence and side effects, and refer to a specialist if indicated. The morbid fear of having an unpredictable seizure not only affects the patients’ physical function, but also emotional well-being, cognitive function, and social function. This study assessed QOL in pediatrics with intractable epilepsy at King Abdullah Specialist Children Hospital, Riyad, Saudi Arabi using The Quality of Life in Childhood Epilepsy (QOLCE-55) scale.[14]

Subjects and Methods

Study design and settings

This is a cross-sectional study utilizing a self-administered questionnaire filled by caregivers of epileptic patients visiting the outpatient neurology clinics between August 2018 and January 2019 at King Abdullah Specialist Children Hospital (KASCH) in Riyadh, the first specialized children hospital in Saudi Arabia (Institutional Review Board approval was obtained on 16-5-2018).

Identification of study participants

This study included a total of 59 caregivers of both genders of Saudi pediatrics aged 4-14 years with intractable epilepsy in KASCH, Riyadh. Non-probability convenience sampling was used in the selection of the subjects. Caregivers of children with intractable epilepsy who agreed to participate in the study were included.

Study instrument and data collection process

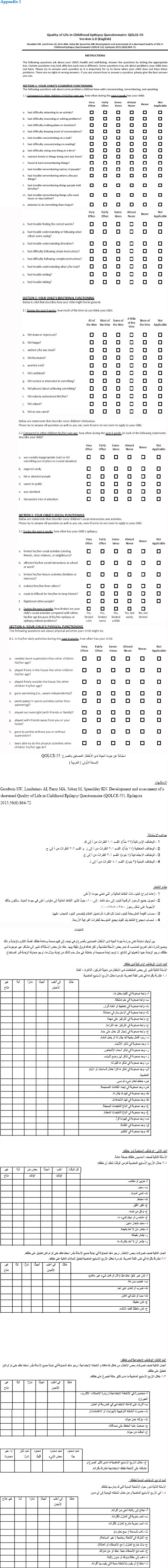

Data were collected by the co-investigators using a self-administered questionnaire. This Questionnaire is composed of a demographic section with characteristics of the epileptic patients like age (in years), gender, and presence of comorbidities. As for QOL, QOLCE-55 was used. QOLCE-55 is a validated questionnaire recommended by The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Common Data Elements to assess the QOL of patients with epilepsy. Parents must answer 55 questions regarding how often do their children experience certain problems compared to other children of their age during the past4 weeks. The QOLCE-55 sections’ included the following domains: cognitive, emotional, social, and physical functioning Each item is on a 6-point Likert scale and includes anchors that are subjectively rated based on perceived QOL (e.g., 1 = very often, 2 = fairly often, 3 = sometimes, 4 = almost never, 5 = never, 6 = non-applicable). Scores are linearly transformed to a 0- to 100-point scale (1 = 0, 2 = 25, 3 = 50, 4 = 75, 5 = 100). Scores are composed of averages for each of the four domains, and an overall QOL score is derived by summing all the individual scores. Higher scores reflect a better QOL. Patients who scores ≥75 are considered to have a good QOL. High internal consistency has been found for the QOLCE. Cronbach's α values ranging from 0.72 to 0.93 across subscales have been reported, with the overall health-related quality of life (HRQOL) score demonstrating internal consistency reliability of 0.93.14 QOLCE-55 was translated into Arabic by native Arabic speakers and pilot tested prior to data collection. English and Arabic versions of QOLCE-55 are attached in Appendix 1.

Ethical approval was sought from King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (KAIMRC) and informed consent was taken from the study subjects. Patients’ confidentiality and privacy were maintained throughout the research.

Data analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages). Numerical data were described as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Independent samples T-test was used to test the association between the scores of the different domains with gender and comorbidities. For testing the association of the scores with age, linear regression was used. Any test was declared significant at a P value < 0.05.

Results

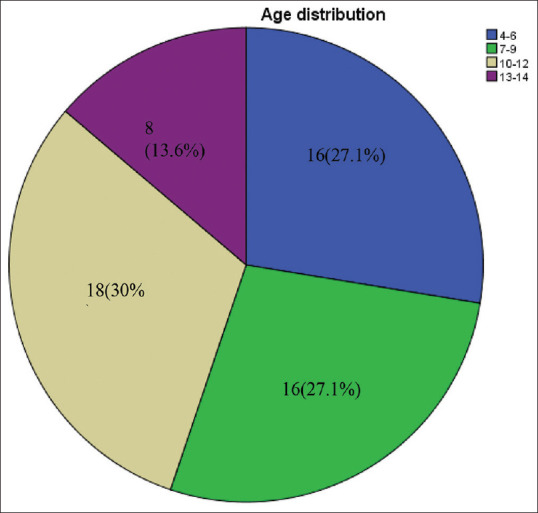

This study included 59 caregivers of both genders of Saudi epileptic children aged 4 − 14 years old. The mean age of children was 8.9 (SD = 2.9) with slightly higher percentage of males, 33 (55.9%). Age distribution is shown in Figure 1. Comorbidities were present in 47 (79.7%) children. Almost a third of the children (28.8%) had global developmental delay (GDD), 5 (8.5%) had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and 4 (6.8%) had encephalopathy. Only 3 patients (5.1%) had spasticity, while 18 (30.5%) children had other comorbidities. Demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Age distribution

Table 1.

Characteristics of epileptic pediatric patients (n=59)

| Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 8.9±2.9 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 33 | 55.9 |

| Female | 26 | 44.1 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| GDD | 17 | 28.8 |

| ADHD | 5 | 8.4 |

| Encephalopathy | 4 | 6.7 |

| Spasticity | 3 | 5.1 |

| Others | 18 | 30.5 |

Regarding the four domains of QOL, cognitive functioning had a mean score of 50.2 (SD = 29.1), emotional functioning a mean score of 49.4 (SD = 13.6), social functioning a mean of 58.7 (SD = 30.3), and physical functioning with a mean of 54.9 (SD = 23.0). The mean total score = 52.8 (SD = 12.9). All domains had low scores which reflects the negative impact of intractable epilepsy on the QOL. Mean scores for all domains of QOL are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean scores for cognitive, emotional, social and physical functioning domains and total QOL score (n=59)

| Mean | SD* | |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive functioning score | 50.2 | 29.1 |

| Emotional functioning score | 49.4 | 13.6 |

| Social functioning score | 58.7 | 30.3 |

| Physical functioning score | 54.9 | 23.0 |

| Total quality of life score | 52.8 | 12.9 |

*Standard deviation

Associations of the scores with the predictors revealed that gender was significantly associated with the social domain (P = 0.001) whereby males had a higher score (70.0, 26.2) compared to females (44.8, 29.7). Gender was also significantly associated with the total score (P = 0.04), and males were also having a better QOL. Although gender was not significantly associated with neither cognitive nor emotional scores (P > 0.05), males were doing better off. Physical score was also not significantly associated with gender (P = 0.17). However, females had a higher score in this domain (59.8, 24.2) compared to males (51.3, 21.7). These results conclude that males have a better QOL compared to females, especially in the social domain. As for age, it was not related to any domain nor the total score (P > 0.05).

Regarding comorbidities’ association with the various domains, GDD (0.3, 0.5) was significantly associated with the total score, cognitive, emotional, and social scores, (P < 0.05). Physical score, on the other hand, was not associated with GDD (P = 0.62). Spasticity (0.1, 0.2) was not found to be associated with the total score (P = 0.16), yet it was associated with the cognitive score (P = 0.007). Furthermore, encephalopathy (0.1, 0.3) was only associated with the total score (P = 0.007) and ADHD (0.1, 0.3) was not associated with any domain nor with the total score. Other comorbidities (0.3, 0.5) were not associated with any score. For all comorbidities which were found to be significant with the quality of life domains, having the comorbidity was associated with lower well-being. In summary, GDD and encephalopathy had a negative association with the QOL, while ADHD had null association with the QOL. Association of scores with predictors is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Association of quality of life scores with predictors in epileptic patients (n=59)

| Predictor | Cognitive score Mean, SD | Emotional score mean, SD | Social score Mean, SD | Physical score Mean, sd | Total score mean, sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 54.1, 29.0 | 50.5,14.1 | 70.0, 26.2 | 51.3, 21.7 | 55.9,12.2 |

| Female | 45.1, 28.9 | 48.2, 13.2 | 44.8, 29.7 | 59.8, 24.2 | 48.9,12.9 |

| P | 0.25 | 0.52 | 0.001* | 0.17 | 0.04* |

| Age, P | 0.94 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.68 | 0.06 |

| GDD, P | <0.001* | 0.003* | 0.002* | 0.62 | 0.02* |

| ADHD, P | 0.90 | 0.39 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.82 |

| Spasticity, P | 0.007* | 0.57 | 0.37 | 0.13 | 0.16 |

| Encephalopathy, P | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.74 | 0.007* |

| Others, P | 0.44 | 0.08 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.45 |

*Statistically significant at P<0.05

Discussion

Epilepsy is a well-known neurological disorder that affects a large scale of the population worldwide. The diagnosis is usually made in childhood or early adolescence.[15] Studies indicate that epileptic children showed poorer QOL compared to patients with other chronic conditions and healthy individuals.[16,17] Patients with intractable epilepsy showed lower scores in both physical and psychological domains than those with other conditions.[16,18] Patients who have intractable epilepsy are at risk of depression and suicide, especially patients who have severe and frequent seizures.[19,20] The predicted prevalence of depression in patients with intractable seizures treated at epilepsy centers is as high as 50%.[19,21,22] The present cross-sectional study investigated the association of certain demographics with cognitive, emotional, social, and physical functioning and the total QOL score in patients with intractable epilepsy.

The current study found that age was not significantly related to any domain nor the total score, these results mismatched with Shetty et al. and Ohaeri et al. who reported a negative association between increasing age and QOL scores of physical pain, emotional well-being, and memory and language domains.[23,24] Taylor et al. found that age was only related to self-esteem, where adolescents had lower scores compared to young children.[25] Nagarathnam et al. results supported the nil association between age group and QOL.[26]

In almost all of the chronic diseases, gender variation plays a major role in the patients’ QOL.[27] Some of the published literature revealed that females are found to have poorer QOL than males.[23,28] In the current study, associations of the QOL domain scores with the predictors revealed that gender was significantly associated with the social domain, and the total score of QOL where males were significantly associated with a better QOL. In a study that showed the correlation between epilepsy and school attendance, females had a higher percentage of absenteeism.[29] On the contrary, Nabukenya et al. results found that being a female is significantly associated with better HRQOL.[30] Other studies reported no significant associations between QOL and gender.[25,26] This wide variation in results might be due to differences in living conditions and needs further evaluation.

In relation to cognitive function, Oyegbile et al. demonstrated that chronicity of seizures correlates with worsening mental status, especially in patients with low cerebral reserve.[31] Gotman reported that verbal memory deficits are related to the impact of refractory epilepsy in patient's lives.[32] These difficulties brought an impact on the daily life once interfering in learning, professional, and social processes.

The current study was in harmony with Mantoan et al. in which clinical characteristics, seizure frequency as well as seizure types had a strong correlation with QOLIE-31 domains of emotional well-being and social function.[33] These characteristics have been considered the most significant predictors of QOL in some studies since patients with more severe seizures reported significantly poorer QOL.[34]

For all comorbidities which were found to be significant with the quality of life domains, having the comorbidity was associated with lower well-being. The current study results were similar to Miller V et al.'s study who reported that co-morbid impairment was the best predictor for poor QOL.[35] Haider S's study also reported similar results.[28]

One of the limitations in the present study is the convenience sampling technique, which can lead to sampling bias.[36] The study was conducted in one hospital, therefore, lacks clear generalizability.[36,37] Unfortunately, reliability and the psychiatric condition of the caregivers were not assessed. Another limitation is the response bias due to the survey-based nature of the study.[38]

Conclusion

Intractable epilepsy impacted all functioning domains of life, rendering a poor QOL. Males reported better QOL and social functioning compared to females. For all comorbidities which were found to be significant with the quality of life domains, having the comorbidity was associated with lower well-being. Specifically, GDD and encephalopathy showed lower well-being. A multi-center study is suggested to increase the sample size in different societies, which may provide a valid and accurate results. Also, a cohort study would be more informative and could provide valuable data.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient has given his/her consent for his/her no images were obtained clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the respondents for participating in the study.

Appendix 1

References

- 1.Kumar P, Clark M. Kumar & Clark's Clinical Medicine. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Who.int. [Internet] Epilepsy: The disorder. 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/Epilepsy_disorder_rev1.pdf .

- 3.Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Benn EK, Katri N, Cascino G, Hauser WA. Estimating risk for developing epilepsy: A population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota. Neurology. 2011;76:23–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318204a36a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace H, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Age-specific incidence and prevalence rates of treated epilepsy in an unselected population of 2,052,922 and age-specific fertility rates of women with epilepsy. Lancet. 1998;352:1970–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04512-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotsopoulos IA, van Merode T, Kessels FG, de Krom MC, Knottnerus JA. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence studies of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures. Epilepsia. 2002;43:1402–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.t01-1-26901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pati S, Alexopoulos A. Pharmacoresistant epilepsy: From pathogenesis to current and emerging therapies. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77:457–67. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. New Engl J Med. 2000;342:314–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker G, Jacoby A, Buck D, Stalgis C, Monnet D. Quality of life of people with epilepsy: A European study. Epilepsia. 1997;38:353–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1997.tb01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobau R, Zahran H, Thurman DJ, Zack MM, Henry TR, Schachter SC, et al. Epilepsy surveillance among adults-19 States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott I, Lach L, Smith M. I just want to be normal: A qualitative study exploring how children and adolescents view the impact of intractable epilepsy on their quality of life. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7:664–78. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abbas Z, Elseed MA, Mohammed IN. The quality of life among Sudanese children with epilepsy and their care givers. Sudan J Paediatr. 2014;14:51–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subki A, Mukhtar A, Al-Harbi R, Alotaibi A, Mosaad F, Alsallum M, et al. The impact of pediatric epilepsy on children and families: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2018;14:323–33. doi: 10.2174/1745017901814010323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha S, Siddiqui KA. Definition of intractable epilepsy. Neurosciences. 2011;16:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauryn C, Elysa W, Mary LS, Kathy NS, Mark AF. Validating the shortened Quality of Life in Childhood Epilepsy Questionnaire (QOLCE-55) in a sample of children with drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2017;58:646–56. doi: 10.1111/epi.13697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Who.int. [Internet] Epilepsy. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy .

- 16.Haneef Z, Grant ML, Valencia I, Hobdell EF, Kothare SV, Legido A, et al. Correlation between child and parental perceptions of health-related quality of life in epilepsy using the PedsQL.v4.0 measurement model. Epileptic Disord. 2010;12:275–82. doi: 10.1684/epd.2010.0344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreira H, Carona C, Silva N, Frontini R, Bullinger M, Canavarro MC. Psychological and quality of life outcomes in pediatric populations: A parent–child perspective. J Pediatr. 2013;163:1471–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet] Measuring healthy days: Population assessment of health-related quality of life. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/pdfs/mhd.pdf .

- 19.Kimiskidis VK, Triantafyllou NI, Kararizou E, Gatzonis SS, Fountoulakis KN, Siatouni A, et al. Depression and anxiety in epilepsy: The association with demographic and seizure-related variables. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacoby A, Baker GA, Steen N, Potts P, Chadwick DW. The clinical course of epilepsy and its psychosocial correlates: Findings from a U.K. community study. Epilepsia. 1996;37:148–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones JE, Hermann BP, Barry JJ, Gilliam F, Kanner AM, Meador KJ. Clinical assessment of Axis I psychiatric morbidity in chronic epilepsy: A multicenter investigation. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:172–9. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanner AM, Soto A, Gross-Kanner H. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of postictal psychiatric symptoms in partial epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;62:708–13. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113763.11862.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shetty PH, Punith K, Naik RK, Saroja AO. Quality of life in patients with epilepsy in India. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2011;2:33–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.80092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohaeri JU, Awadalla AW, Farah AA. Quality of life in people with epilepsy and their family caregivers. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1328–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor J, Jacoby A, Baker GA, Marson AG. Self-reported and parent-reported quality of life of children and adolescents with new-onset epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1489–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagarathnam M, Vengamma B, Latheef SA, Reddemma K. Assessment of quality of life in epilepsy in Andhra Pradesh. Neurol Asia. 2014;19:249–55. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigneshwaran E, Reddy YP, Devanna N. Enhancing quality of life and medication adherence through patient education and counseling among HIV/AIDS patients in resource limited settings-pre and post interventional pilot trial. Br J Pharm Res. 2013;3:485–95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haider S, Mahmood T, Hussain S, Nazir S, Shafiq S, Hassan A. Quality of life in children with epilepsy in Wah Cantt, Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. JRMC. 2020;24:128–33. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassen O, Beyene A. The effect of seizure on school attendance among children with epilepsy: A follow-up study at the pediatrics neurology clinic, Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Pediatr. 2020;20:270. doi: 10.1186/s12887-020-02149-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nabukenya AM, Matovu JK, Wabwire-Mangen F, Wanyenze RK, Makumbi F. Health-related quality of life in epilepsy patients receiving anti-epileptic drugs at National Referral Hospitals in Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:49. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oyegbile TO, Dow C, Jones J, Bell B, Rutecki P, Sheth R, et al. The nature and course of neuropsychological morbidity in chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 2004;62:1736–42. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000125186.04867.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones-Gotman M, Harnadek MC, Kubu CS. Neuropsychological assessment for temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(Suppl 1):S39–43. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dourado MV, Alonso NB, Martins HH, Oliveira ARC, Vancini RL, Lima CD, et al. Quality of life and the self-perception impact of epilepsy in three different epilepsy types. J Epilepsy Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;13:191–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mrabet H, Mrabet A, Zouari B, Ghachem R. Health-related quality of life of people with epilepsy compared with a general reference population: A Tunisian study. Epilepsia. 2004;45:838–43. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.56903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller V, Palermo TM, Grewe SD. Quality of life in pediatric epilepsy: Demographic and disease-related predictors and comparison with healthy controls. Epilepsy Behav. 2003;4:36–42. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jager J, Putnick DL, Bornstein MH. More than just convenient: The scientific merits of homogeneous convenience samples. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2017;82:13–30. doi: 10.1111/mono.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leung L. Validity, reliability, and generalizability in qualitative research. J Family Med Prim Care. 2015;4:324–7. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.161306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavrakas P. Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods [Internet] 2008. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/reference/encyclopedia-of-survey-research-methods .