Abstract

The growing gender gap in educational attainment between men and women has raised concerns that the skill development of boys may be more sensitive to family disadvantage than that of girls. Using the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) data we find, as do previous studies, that boys are more likely to experience increased problems in school relative to girls, including suspensions and reduced educational aspirations, when they are in poor quality schools, less-educated neighborhoods, and father-absent households. Following these cohorts into young adulthood, however, we find no evidence that adolescent disadvantage has stronger negative impacts on long-run economic outcomes such as college graduation, employment, or income for men, relative to women. We do find that father absence is more strongly associated with men’s marriage and childbearing and weak support for greater male vulnerability to disadvantage in rates of high school graduation. An investigation of adult outcomes for another recent cohort from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 produces a similar pattern of results. We conclude that focusing on gender differences in behavior in school may not lead to valid inferences about the effects of disadvantage on adult skills.

Keywords: Gender, education, employment, earnings, family structure, father absence, school quality, neighborhood effect

JEL Classification: J24, J12, J16

1. Introduction

In 1990, the proportion of young women (aged 25 to 29) who had completed four-year college degrees reached near equality with young men in the United States after steadily increasing for several decades. By 2014, the long-standing gender gap in educational attainment had not just disappeared but reversed—favoring women by a substantial margin. More than 37 percent of young women now have at least a four-year college degree, compared to less than 31 percent of young men (U. S. Census, 2016b). Similar gender gaps in education are opening up around the world, with young women completing tertiary degrees at higher rates than men in almost all OECD countries (OECD, 2015).

Rising female educational attainment has been a consequence of the removal of barriers to women’s schooling and market work that had discouraged investments in women’s human capital. However, the emergence of a female advantage in higher education rather than parity, even though women continue to have lower employment rates and shorter work hours than men, has been unexpected. Some studies find a gender gap in benefits to education, such as a higher college wage premium for women than for men (Dougherty, 2005) but a consensus seems to be emerging that the principal source of the college gap lies in gender differences in the non-pecuniary costs of educational persistence. These cost differences are reflected in a persistent male disadvantage in school performance at all levels and are due, some argue, to lower levels of non-cognitive skills among boys and the resulting “behavioral advantage” of girls (Fahle and Reardon, 2018).

An extensive literature in education and the social sciences has documented gender differences in the academic and behavioral outcomes of boys and girls in elementary and secondary school (Buchmann, DiPrete, and McDaniel, 2008; DiPrete and Buchmann, 2013; Salisbury, Rees, and Gorard, 1999). These gender gaps are not new phenomena: girls have consistently outperformed boys in grades and have been less likely to get in trouble at school (Duckworth and Seligman, 2006). Recent studies interpret the observed gender differences in academic performance, grade repetition, special education placement, homework hours and school reports of disruptive behavior as indicative of gaps between the non-cognitive skills of boys and girls (Becker, Hubbard, and Murphy, 2010; Goldin, Katz, and Kuziemko, 2006; Jacob, 2002). Gender gaps in social and behavioral skills appear to develop early—girls begin school with more advanced learning and social skills than boys, and this advantage grows over time. These early skill gaps, in turn, explain much of the gender differential in later academic achievement and educational attainment (DiPrete and Jennings, 2012; Owens, 2016).

Economists have focused on possible causes of this gender gap in behavior, including the possibility that the development of capabilities that enhance academic achievement, such as self-control, is more sensitive to family disadvantage among boys than is the skill development of girls. Autor and Wasserman (2013) suggest that the increased prevalence of single-parent families and decreased contact with a stable male parent may have a particularly negative impact on boys and contribute to the growing gender gap in education and to male labor market difficulties, either because boys are more vulnerable to the loss of parental time and financial resources, or due to role model effects of the same-sex parent.1 Two recent studies report empirical evidence consistent with this hypothesis. Bertrand and Pan (2013) find that the gender gap in early behavior problems and school suspensions is much larger for the sons and daughters of single mothers than for children in two-parent households. They interpret this as evidence that the non-cognitive skills of boys are adversely impacted by non-traditional family arrangements, and suggest that boys’ greater tendency to act out and develop conduct problems might be particularly relevant to their relative absence in college. Autor, Figlio, Karbownik, Roth, and Wasserman (2019) examine the effects of several dimensions of family disadvantage, including mother’s education and marital status, an SES index, neighborhood income and school quality on school performance, behavior, and on-time high school graduation for a large sample of children in Florida. They find that indicators of family disadvantage tend to have significantly greater effects on school outcomes for boys, compared to girls.

In this study, we move beyond K-12 achievement and behavior to assess the role of excess male vulnerability to adverse childhood environments in explaining gender gaps in college graduation and other adult outcomes. This requires data that permits us to link family structure and characteristics of schools and neighborhoods in childhood with longer-term outcomes, including final educational attainment, and we use rich longitudinal data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). In particular, we examine the association between family disadvantage in adolescence and outcomes that include behavior in school, mental health and educational aspirations in adolescence, and educational attainment, employment, income, marriage and fertility in adulthood, for a recent cohort of young adults.

We find, as do previous studies, that boys are more sensitive than girls to father absence in terms of problems with schoolwork and interactions in school. Girls, however, are more likely than boys to respond to father absence with increased levels of depression, and are particularly negatively affected by residence with a stepfather. When we turn to educational attainment and other adult economic outcomes in later waves of Add Health, we find that family structure in adolescence does not have differential effects on the college graduation rates, income, and job stability of men and women. Family structure in adolescence does differentially affect men and women in terms of family decisions in young adulthood, including marriage and fertility. Results using data of another recent cohort of young adults from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 produce a similar pattern of results. In addition we find, as do Autor et al. (2019), that the behavior of adolescent boys is more responsive to other indicators of disadvantage, such as poor quality schools and less-educated neighborhood, than is the behavior of girls. These differential environmental effects, however, also fail to persist into adulthood.

A few other studies have focused on gender differences in the adult impacts of early life disadvantage. Closest to our design is Brenøe and Lundberg (2018), who are able to assess some long-term effects of family disadvantage with Danish administrative data. Linking entire population cohorts from birth into adulthood, they find that family disadvantage, particularly low maternal education, has more negative effects on school-age outcomes of boys relative to girls, as expected. Administrative data provides few adolescent measures; the key outcome is a marker for completing primary school on time. Long-term effects are quite different: early disadvantage, particularly low parental education, tends to have stronger impacts on the educational attainment, employment, and earnings of adult women, compared to adult men.2

Slade, Beller, and Powers (2017), who also use the Add Health data, find a stronger association between nontraditional family structure in childhood and health outcomes, including depression, self-reported health and smoking, for girls compared to boys. They also find that many of the effects of father absence on health and mental health outcomes in adolescence, including depression, are no longer significant in young adulthood. Autor et al. (2019) find that mother’s marital status and education have larger effects on son’s high school graduation than daughter’s, but are not able to follow subjects further into college and employment. Fan, Fang, and Markussen (2015) use Norwegian administrative data to show that mother’s employment early in a child’s life is more negatively associated with the educational attainment of sons than daughters, suggesting that they are more adversely affected by a reduction in maternal time. Finally, Gould, Lavy, and Paserman (2011) present contrary results in a different environment–Yemenite child refugees in Israel who were placed in more modern environments achieved higher education and employment rates, but these benefits accrued largely to women.

Our results, which show that short-run differential impacts of disadvantage on boys and girls are not reflected in long-term outcomes, cast doubts on interpreting the gender differences in the impacts of disadvantage in school as evidence on excess male vulnerability in terms of non-cognitive skills. If adolescent disadvantage has differential impacts on non-cognitive skills for boys and girls, we would expect the gender differences to persist into adulthood, affecting long-run outcomes such as college graduation and labor market performance that are highly correlated with non-cognitive skills. Instead, school-age boys and girls appear to respond to adolescent environments and resources with distinct, gender-typical behaviors that haven’t been previously noted in this context, rather than developing a skill gap with implications for adult economic outcomes, such as the gender gap in college graduation. Though non-traditional family structures and adverse environments in adolescence are associated with lower educational attainment and poor labor market outcomes for both men and women, we fail to reject the hypothesis that adolescent disadvantage does not have differential effects across gender on college graduation rates and labor market outcomes. Disadvantage in adolescence does have some distinct effects on marriage and fertility for men and women, but we find little evidence supporting a general pattern of excess male vulnerability.

2. Data

2.1. Add Health Sample

The National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) has collected a rich array of longitudinal data on the social, economic, psychological and physical well-being of young men and women in the U.S. from adolescence through young adulthood.3 The Add Health study began in 1994-95 with a nationally-representative school-based survey of more than 90,000 students in grades 7 through 12. The students were born between 1976 and 1984 and attended one of 132 schools in the sampling frame. About 20,000 respondents were followed in subsequent surveys; the last completed survey (Wave IV) was conducted in 2007-08 when the respondents were between 24 and 32 years of age.

Most of our analysis is based on a subsample of white, non-Hispanic men and women. Father-absent households are much more prevalent in the Black and Hispanic Add Health samples, and school and neighborhood characteristics are also very different on average. Because our focus is on gender differences in the impact of adolescent environments, and these may differ between, for example, households with foreign-born vs. native-born parents or schools with disciplinary regimes of varying harshness, we have chosen to focus on a more homogenous core sample. Key results for the Black subsample are presented in section 4.5; the Hispanic subsample is too small to support a separate analysis.

Table A1 illustrates the selection of our Add Health analysis sample: the columns present mean values for the full Add Health Wave I sample, the full sample with complete data on key variables, the white, non-Hispanic sample, this sample with only those living with biological mother at Wave I and with non-missing maternal characteristics, and finally the sample remaining in the survey at Wave IV. This, the final analysis sample, contains 3,868 non-Hispanic white women and 3,459 non-Hispanic white men. With the exception of the race/ethnic subsampling, these sample restrictions have very little impact on the demographics of the sample.4 The descriptive statistics by gender for this sample are summarized in Table A2.

2.1.1. Adolescent Outcomes

The Add Health Wave I survey collected an array of student-reported variables, including experiences in school, health, personality, and relationships with parents, siblings, friends and others. Most respondents were between the ages of 12 and 17. We use self-reports of Math and English grades and of school problems, including school suspensions, to generate academic and behavioral outcomes that are similar to those in previous studies such as Autor et al. (2019) and augment this with a standard depression scale and reports of educational aspirations. The principal advantage offered by the Add Health data over the Danish data used by Brenøe and Lundberg (2018), who also compared in the impact of family disadvantage in adolescence and adulthood is this broad array of school-age outcomes, compared to a restricted set of measures available in administrative data.

School Problems: Students were asked about problems they experience in school, including trouble getting along with teachers and other students, trouble getting homework done and trouble paying attention in class (coded 0-4 from never to every day), how many times they have been absent without an excuse, and whether they have ever received an out-of-school suspension. Factor analysis was used to aggregate these measures into a standardized school problems index.5 Misbehavior in school, including absenteeism, inattention, and suspensions, are strongly predictive of adult labor market outcomes and criminal behavior (Segal, 2013; Lundberg, 2017b) and school suspensions are a key outcome in both Bertrand and Pan (2013) and Autor et al. (2019). In our sample, the proportion of boys who report ever having been suspended is more than twice that of girls, and their level of school problems is 0.3 standard deviations higher (Table A2).

Depression: Wave I respondents were asked how often during the past week they felt sad, lonely, depressed, blue, happy, or hopeful. These six items (plus 13 more) are the components of CES-D, a standard depression scale (Radloff, 1977). Factor analysis indicated that a single factor is appropriate for these 19 items and was used to form a standardized depression index. Table A2 shows that reported depression among adolescent girls is much higher than among boys.

Grades and Aspirations: As a measure of academic achievement, we use student reports of their math and English grades in the most recent grading period. Girls’ mean English grade is 0.375 grade points higher than boys’, but their math grades are only slightly higher on average (Table A2). Educational aspirations in Wave I are based on student responses (on a 5-point scale) as to how much they want to attend college, and how likely they think it is that they will attend college. Add Health respondents are very optimistic about their college prospects on average, but girls are substantially more likely to report that they both want and expect to attend. Fortin, Oreopoulos, and Phipps (2015) find that much of the gender gap in high school achievement can be attributed to the gender difference in educational expectations, particularly those linked to career plans that include a graduate degree. Add Health students were also asked about how likely they are to be married at age 25, on a 5-point scale.

2.1.2. Adult Outcomes

Our principal goal is to examine whether deficits in early skills and aspirations due to family disadvantage have long-term implications for gender gaps in economic and social outcomes in adulthood. The Wave IV survey collected an array of adult outcomes, including educational attainment, employment and income, and family histories.

Educational Attainment: Highest educational attainment is collected when most respondents are between 25 and 31 years of age. Most, though not all, will have completed their final level of formal schooling at this point. We focus on the attainment of a 4-year college degree, since the rising returns to education in recent decades have largely been restricted to college graduates. Though there is a gender gap in high school graduation and college attendance as well, the college graduation gap has received the most attention given its substantial implications for lifetime income. However, we also examine high school graduation, imputed years of schooling, and a categorical education variable that ranges from 0=less than high school to 5=post-graduate degree. As expected, we see a moderate gender gap in high school graduation rates and a substantial one in college graduation in our analysis sample (Table A2).

Employment and Income: Deficits in non-cognitive skills and limited schooling are likely to lead to adverse labor market outcomes. We examine self-reported before-tax personal earnings, and define respondents as currently employed if they report working for pay at least 10 hours a week. We also consider two other aspects of employment histories: number of times fired6 and satisfaction with current or last job7, as these may reflect non-cognitive skills. A dummy variable for financial stress is based on respondent reports that they have faced difficulties in paying bills in the past year.8 This measure is likely to be driven both by economic resources and by skills associated with managing those resources. Male respondents are, as expected, more likely to be employed than women, and also report higher earnings and lower levels of financial stress. Men are more likely to report being fired than women and have roughly equivalent levels of job satisfaction.

Marriage and Children Ever Born: Marriage and fertility histories are collected in the Wave IV survey. Half of the Add Health respondents have never been married at the time of Wave IV survey; we focus on a dummy variable for ever married as our key outcome. The respondents were also asked about the number of times they have been pregnant/have made a partner pregnant, and the live births resulting from these pregnancies. Add Health men are less likely to have been married and report fewer children than women, reflecting the expected gender differences in the timing of family formation.

Depression: The Wave IV survey includes a shorter (11 item) version of the depression instrument in Wave I, and we include this in the analysis to see how persistent family and environmental influences on this mental health indicator are.9

2.1.3. Indicators of Disadvantage in Adolescence

Father Absence in Wave I: A large literature has documented the empirical relationship between single parenthood, family instability, and a child’s prospects for success in adulthood (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Lopoo and DeLeire, 2014; Woessmann, 2015), though causal inference has been difficult given the confounding effects of unobserved parental, child, and environmental characteristics. The restricted economic and parental resources in single-parent families are very likely, however, to limit investments in children and adolescents. Though nearly 90 percent of the Add Health respondents were living with their biological mother in Wave I, almost 10 percent were also living with a step-father or other father figure rather than their biological or adoptive father, and nearly 22 percent were living with no father figure at all. Girls were 15 percent more likely to be living with no father in the household than were Add Health boys.

School Quality: Autor et al. (2019) find that poor quality schools have a particularly disadvantageous effect on school outcomes for boys and that this environmental influence is distinct from the effects of family disadvantage. The Add Health Study includes a school administrator questionnaire that can be used to construct a standardized index of school quality for the schools attended in Wave I.10 The components of the index are average daily attendance, class size, percentages of new and of experienced teachers, the share of teachers with a Masters degree, grade 12 dropout rates, percentages of students with standardized achievement tests at, below, or above grade level, and the share of 12th graders who enrolled in a 2-year or 4-year college the next year.

Neighborhood: A growing literature finds that neighborhood characteristics appear to have long-term causal impacts on economic outcomes for children, and that boys may be differentially sensitive to these forces (Chetty et al., 2016; Chetty and Hendren, 2018; Autor et al., 2019). The Add Health Contextual Database provides an array of community characteristics that enable researchers to investigate contextual influences for a wide range of adolescent behaviors.11 We use an indicator for “educated neighborhood” defined as the proportion of individuals aged 25+ with a college degree or more at the census tract level.

2.1.4. Maternal Characteristics

Maternal characteristics are included as control variables in most regressions. The educational attainment of the respondent’s biological mother is divided into 4 categories, “less than high school”, “high school degree”, “some college”, and “college degree or more”. We also included indicators for whether the biological mother is foreign-born and young (under age 22) at the birth.

2.2. NLSY97 Sample

We examine the robustness of our analysis of Add Health with the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), which provides comparable measures of adult (but not comparable adolescent) outcomes for a set of birth cohorts similar to Add Health. NLSY97 is a representative longitudinal study with surveys from 1997 (round 1) to 2015-2016 (round 17). The cohort was born between 1980 and 1984, with respondents aged between 12 and 18 at the time of the first interview and between 30 and 36 at round 17. As in our Add Health models, we analyze a subsample of non-Hispanic white women and men. Details regarding the sample, variable construction, and a comparison with the Add Health sample are in the Data Appendix.

3. Empirical Strategy

Obtaining a causal estimate of the difference in the impacts of father absence and other indicators of family disadvantage on outcomes for boys and girls requires that the distribution of male and female children across households with and without fathers be identical in terms of their potential outcomes with a father present. For any outcome Y for boys (b) and girls (g), we can define possible outcomes in alternative family structures as:

where Yi(0) is the potential outcome of child i if his or her father is present in the household (D = 0), and Yi(1) is the potential outcome if his or her father is absent (D = 1). Yi is the observed outcome.

In general, the causal impact of father absence cannot be determined by comparing outcomes for children in different types of household due to the confounding effects of unobserved parental, child, and environmental influences. The average difference in outcomes between boys in father-absent and father-present households is:

The first term is the average causal impact of father absence for boys raised in father-absent households; the second term is selection bias–the difference between potential outcomes in the father-present state between boys who were raised in that state and boys who were not. This will generally be non-zero, and any estimate of the effect of father absence will be biased if there are unobserved differences in child capabilities and mother characteristics in father-present and father-absent households. This is true for girls as well.

However, if the selection terms are identical for boys and girls, an estimate of the gender difference in the effects of father absence will be unbiased. If we have:

Assumption 3.1 (Non-differential Selection)

then the gender difference in the causal effects of father absence is identified (equation 3.1). Alternatively, we can define under Assumption 3.1 an unbiased estimate of the causal effect of father absence on gender gaps (equation 3.2).

| (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

The main econometric specification in this paper is:

| (3.3) |

where NFi is a dummy variable equal to one if child i lived in a household with no father figure in the baseline survey and OFi is equal to one if a non-biological, non-adoptive father, such as a step-father, lived in the household. Xi includes maternal characteristics and the child’s birth cohort. Standard errors are clustered by the school attended in Wave I. The coefficients of interest–β1 and β2–identify the gender difference in the causal effects of father absence and other father, under Assumption 3.1.

Therefore, the interpretation of the results as causal relies on the key identification assumption that selection into father absence and other father households is identical for boys and girls. Estimates may not be unbiased if father absence and child gender are not independent, and the fact that girls are more likely to live in father-absent households than boys raises the possibility of selection on child or maternal characteristics. One mechanism driving this gap may be parental decisions about marriage and custody that are child gender-specific: fathers are more likely to co-reside with, seek custody of, and marry the mothers of their sons rather than their daughters (Lundberg and Rose, 2003; Dahl and Moretti, 2008; Lundberg, 2005). Another may be through the effects of parental circumstances on the gender mix of offspring: evidence is mounting that prenatal stress (which may be related to partnership status) has differential impacts on the mortality of male and female fetuses, though the effects are small (Almond and Edlund, 2007; Hamoudi and Nobles, 2014, Norberg, 2004).

Table A4 presents a test for the identification assumption. If selection into father absent and other father households is identical for boys and girls, then the gaps in pre-determined characteristics between father-absent/other-father household and father-present household should be the same for boys and girls. We do find that mother’s characteristics and family income is often significantly associated with family structure, but there is no evidence that the selection is different across gender: none of the interaction terms are significantly different from 0.12 Another possible concern is selective attrition in this longitudinal study. We define attrition as the sample size reduction when conditioning on appearance in Wave IV (i.e. the change from column (4), Table A1 to column (5), Table A1). As shown in Column (8), Table A4, boys and adolescents in father-absent households are more likely to attrit before Wave IV, but attrition is not different across gender/family structure categories. These results indicate that there is no evidence that our identification assumption is violated in this sample.13,14

4. Results

4.1. Adolescent Outcomes

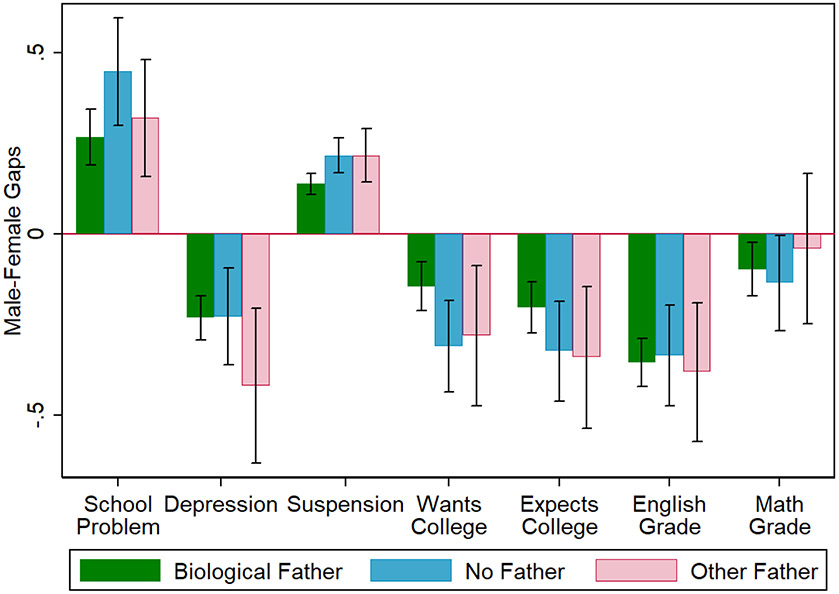

Gender gaps in the behavior and achievements of school children in the Add Health sample are shown in Figure 1 for the three family structure groups: biological father present, no father, and other father. The gender gaps in the school problems index, depression index, school suspensions, and educational aspirations are relatively larger for respondents in non-traditional families. Therefore, Figure 1 provides some raw evidence that the effects of family structure on adolescent outcomes may differ by gender.

Figure 1: Gender Gaps in Adolescent Outcomes by Family Structures, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample.

Note: This figure displays the coefficient of “Male” dummy, when regressing the outcomes on “Male” dummy and a constant, with its 95% confidence interval. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “School problems” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A5. “Depression” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A6. Grades are student-reported and range from 1=D or lower to 4=A. College desires/expectations are standardized measures based on a 0-4 scale. All models are weighted by Wave I weights.

Estimates of equation 3.3 showing the effects of father absence in Wave I on adolescent outcomes are reported in Table 1. Columns (1) and (2) show that living in a father absent household or step-father household is positively associated with school problems and school suspensions, and that this association (particularly for no-father households) is significantly greater for boys than for girls.15 The results for school suspensions in particular are strongly consistent with the findings of both Bertrand and Pan (2013) and Autor et al. (2019).16 In these results we see some evidence of differential male susceptibility to non-traditional family structures.

Table 1:

Adolescent Outcomes, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | School Problem Index |

Ever Suspended from School |

Depression Index |

English Grade |

Math Grade |

Wants to Attend College |

Expects to Attend College |

Chance of Being Married by Age 25 |

| Male | 0.263*** (0.0384) |

0.136*** (0.0140) |

−0.240*** (0.0295) |

−0.361*** (0.0320) |

−0.0925** (0.0390) |

−0.143*** (0.0319) |

−0.216*** (0.0342) |

−0.119*** (0.0297) |

| Male*No Father | 0.179** (0.0787) |

0.0741*** (0.0263) |

−0.000464 (0.0663) |

0.0365 (0.0771) |

−0.0261 (0.0720) |

−0.147** (0.0652) |

−0.0943 (0.0763) |

0.0232 (0.0771) |

| Male*Other Father | 0.0466 (0.0884) |

0.0682* (0.0368) |

−0.205* (0.115) |

0.00603 (0.0969) |

0.0738 (0.120) |

−0.102 (0.104) |

−0.0930 (0.105) |

−0.0232 (0.0895) |

| No Father | 0.175*** (0.0569) |

0.102*** (0.0191) |

0.184*** (0.0489) |

−0.248*** (0.0529) |

−0.198*** (0.0518) |

−0.00407 (0.0476) |

−0.167*** (0.0528) |

−0.243*** (0.0525) |

| Other Father | 0.146** (0.0702) |

0.0366* (0.0191) |

0.272*** (0.0969) |

−0.0827 (0.0641) |

−0.144 (0.0886) |

0.0215 (0.0619) |

−0.0502 (0.0769) |

−0.174*** (0.0627) |

| Constant | −0.999*** (0.353) |

−0.505*** (0.143) |

−1.651*** (0.260) |

3.478*** (0.333) |

3.974*** (0.376) |

1.478*** (0.264) |

0.169 (0.277) |

1.370*** (0.285) |

| Observations | 7,203 | 7,325 | 7,311 | 7,068 | 6,755 | 7,309 | 7,308 | 7,291 |

| R-squared | 0.050 | 0.120 | 0.063 | 0.091 | 0.038 | 0.090 | 0.136 | 0.020 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.000 | 0.207 | 0.000 | 2.918 | 2.789 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Mother’s characteristics | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors clustered by school.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “School problems” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A5. “Depression” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A6. Grades are student-reported and range from 1=D or lower to 4=A. College desires/expectations and expectation of chance of being married by age 25 are standardized measures based on a 0-4 scale. Mothers characteristics include education and dummies for foreign-born and young mother (under 22). All models include birth cohort. All models are weighted by Wave I weights.

A different picture emerges when we look at another set of Wave I self-reports: depression in adolescence. Column (3) shows the effects of family structure on the depression index. Boys are significantly less likely than girls to report experiencing negative emotions, and youth in no-father and step-father families are more likely to make such reports. We find that depression is more strongly associated with living with a step-father or other father figure for girls than for boys, and the interaction term is also significant for several depression index components (Table A6). Depression is one example of an “internalizing” response to stress that is more common for girls, as opposed to the “externalizing” or disruptive behavior more typical of boys (Leadbeater, Kuperminc, Blatt, and Hertzog, 1999).

Family structure does not appear to have any differential effect on self-reported grades in English and Math, though we find the usual pattern that boys’ grades are lower than girls, particularly in English (Column (4)-(5), Table 1). When asked in Wave I about their college plans, Add Health boys are less likely than girls to report either that they want to attend college or that they expect to attend college (Column (6)-(7), Table 1). In this case, living in a household with no father appears to have a more severe effect on the college intentions of boys–they are substantially less likely to report a strong desire to attend college than girls in similar families.

The results in this section both reinforce and expand upon the findings of previous studies that show excess vulnerability of school-aged boys in the face of family disadvantage and father absence. The gender gap in school problems is much greater for adolescents who are not living with both biological parents, and this pattern is consistent with earlier studies that find increasing gender gaps in schools suspensions and externalizing behavior. Examining an aspect of problematic internalizing behavior, depression, indicates that girls may have distinctive responses to family disadvantage not reflected in standard measures of school achievement and disciplinary outcomes. These contrasting results show that our conclusions about which gender is more sensitive to father absence may depend on which school outcomes we are measuring.

What are the mechanisms underlying these results? One possible source of these differences may be sex differences in early developmental trajectories that have implications for skills in adolescence. Beginning in preschool, girls are more mature than boys in language skills and emotional regulation, and this may increase their resilience in some adverse circumstances. The absence of a stable, same-sex parent may also have distinct behavioral effects on boys, as the presence of a step-father appears to have for girls.17 A key implication here is that disadvantaged boys may be left with a deficit of skills, particularly non-cognitive skills, that can further disadvantage them in adulthood. In contrast, a cultural explanation is provided by DiPrete and Buchmann (2013), who argue that developing a masculine self-image may involve a rejection of school values, and that this oppositional culture may be particularly relevant for boys with absent or low-education fathers. The effects of father absence on boys’ desire to attend college may provide some support for this mechanism.

Finally, parental investments in low-resource environments may differ by child gender. Though a large literature shows that, on average, fathers spend more time with sons than with daughters, and that this gap grows with age (Lundberg, 2005), Bertrand and Pan (2013) find that single mothers spend less time with sons than daughters and report less emotional closeness with sons in early school years. Such a result suggests a parental investment variant of the Trivers-Willard hypothesis from evolutionary biology: parents who are maximizing reproductive success invest more in male offspring in good conditions but more in females in poor conditions (Trivers and Willard, 1973). Explicit attempts to test for evidence of Trivers-Willard patterns in modern families, however, have not found it to be well-supported (Keller, Nesse, and Hofferth, 2001).

The Add Health survey has limited direct measures of parental inputs, but does include multiple indicators of the quality of the parent-child relationship, which may be related to parental investments. Adolescent reports in Wave I about their relationships with parents do not show any evidence of such distinctive boy-girl responses to father absence (Table A7). Children in father-absent families are less likely to report that their parents care about them, that their family generally has fun, that their mothers are warm and loving towards them, and that they are satisfied with their relationship with their mother, but we find no significant gender differences in these family structure effects.

4.2. Educational Attainment

Do the gender-differential effects of father absence in adolescence persist into adulthood? The effects of father absence in adolescence on several measures of educational attainment from Wave IV of the Add Health Study, when the respondents are in their late twenties and early thirties, are reported in Tables 2-3. Table 2 shows that being male has a large negative effect on the probability that an Add Health respondent receives a 4-year college degree. In the initial model with no other covariates, the college gender gap is 7 percentage points and controlling for mothers characteristics (Columns (2)-(6)) has little effect on this gap. The coefficients on dummy variables for living in a family with no father figure or with a non-biological (step) father figure in Wave I are also large and negative.

Table 2:

College Graduation, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Living with Bio-mon in Wave I | Mother High School |

Mother Some College |

Mother College Grad |

||

| Male | −0.0702*** (0.0169) |

−0.0893*** (0.0178) |

−0.0891*** (0.0179) |

−0.0600*** (0.0215) |

−0.0916* (0.0489) |

−0.136*** (0.0338) |

| Male*No Father | 0.0397 (0.0296) |

0.0352 (0.0358) |

−0.0212 (0.0826) |

0.0691 (0.0750) |

||

| Male*Other Father | 0.0366 (0.0423) |

0.0365 (0.0423) |

0.0231 (0.0460) |

0.00942 (0.0962) |

0.0802 (0.101) |

|

| No Father | −0.149*** (0.0209) |

−0.130*** (0.0241) |

−0.133*** (0.0467) |

−0.235*** (0.0556) |

||

| Other Father | −0.126*** (0.0264) |

−0.127*** (0.0264) |

−0.107*** (0.0333) |

−0.0958 (0.0639) |

−0.207*** (0.0670) |

|

| Male*No Father Recently | 0.0326 (0.0421) |

|||||

| Male*No Father Always | 0.0368 (0.0329) |

|||||

| No Father Recently | −0.106*** (0.0283) |

|||||

| No Father Always | −0.192*** (0.0235) |

|||||

| Constant | 0.155 (0.217) |

−0.123 (0.168) |

−0.105 (0.167) |

−0.00228 (0.204) |

−0.0192 (0.299) |

0.590** (0.261) |

| Observations | 7,327 | 7,327 | 7,327 | 3,932 | 1,468 | 1,922 |

| R-squared | 0.006 | 0.171 | 0.172 | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.063 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.368 | 0.235 | 0.362 | 0.643 | ||

| Mother’s characteristics | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors clustered by school.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “No Father Always” means the adolescent has not lived with his/her biological father since the age of 5. Mothers characteristics include education and dummies for foreign-born and young mother (under 22). All models include birth cohort. All models are weighted by Wave IV weights.

Table 3:

High School Graduation, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Living with Bio-mom in Wave I |

Mother High School |

Mother Some College |

Mother College Grad |

||

| Male | −0.0251*** (0.00821) |

−0.0235*** (0.00837) |

−0.0235*** (0.00837) |

−0.0258* (0.0151) |

−0.0110 (0.0130) |

−0.0140** (0.00576) |

| Male*No Father | −0.0327* (0.0196) |

−0.0298 (0.0291) |

−0.0720 (0.0452) |

−0.00242 (0.0266) |

||

| Male*Other Father | 0.0171 (0.0272) |

0.0170 (0.0273) |

0.0433 (0.0484) |

−0.0171 (0.0360) |

−0.0203 (0.0310) |

|

| No Father | −0.0336** (0.0129) |

−0.0592*** (0.0209) |

−0.0257 (0.0181) |

−0.0124 (0.00969) |

||

| Other Father | −0.0379** (0.0176) |

−0.0380** (0.0176) |

−0.0663** (0.0324) |

0.00108 (0.0178) |

0.000956 (0.00198) |

|

| Male*No Father Recently | −0.0116 (0.0240) |

|||||

| Male*No Father Always | −0.0597* (0.0332) |

|||||

| No Father Recently | −0.0293* (0.0155) |

|||||

| No Father Always | −0.0380* (0.0204) |

|||||

| Constant | 0.796*** (0.0859) |

0.607*** (0.0774) |

0.612*** (0.0788) |

0.761*** (0.117) |

0.809*** (0.126) |

0.906*** (0.0497) |

| Observations | 7,327 | 7,327 | 7,327 | 3,932 | 1,468 | 1,922 |

| R-squared | 0.003 | 0.080 | 0.081 | 0.023 | 0.032 | 0.012 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.935 | 0.900 | 0.958 | 0.988 | ||

| Mother’s characteristics | NO | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors clustered by school.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “No Father Always” means the adolescent has not lived with his/her biological father since the age of 5. Mothers characteristics include education and dummies for foreign-born and young mother (under 22). All models include birth cohort. All models are weighted by Wave IV weights.

Non-traditional family structures do not, however, have differentially negative impacts on the college graduation rates of young men (Column (2)). The interaction effects, expected to be negative if boys are more vulnerable to father absence, are instead positive and insignificant. Column (3) decomposes the no father group into young adults who, though they did not live with their biological father at Wave I, did do so after the age of 5 (No Father Recently) and those who never lived with their father after age 5 (No Father Always). The latter status, as expected, has a larger negative association with college graduation but the gender interaction effects are once again positive, small and insignificant. Columns (4)-(6) report results from the core model for subsamples based on mother’s education level, and the pattern is similar–negative effects of non-traditional family structures, but no evidence that the college graduation rates of men are more strongly affected by father absence than is college graduation by women.

The results in Table 3 show similar patterns in the determinants of high school graduation. Men are less likely to graduate from high school than women, living with no father or a step-father in Wave I has a strong negative association with graduation. There is weak support for greater male vulnerability to disadvantage: the interaction term of Male and No Father is marginally significant at the 10% level. The impact of father absence before age 5 (No Father Always) on men’s high school graduation, compared to women’s, is also marginally significant at a 10% level. Columns (4)-(6) split the sample by mother’s education and show that the effects of family structure on men’s high school graduation appear to be concentrated in families in which the mother had some college education, though none of the interaction terms are individually significantly in these subsamples.

Table A8 reports the results of key models for two alternative measures: years of completed education and a categorical measure of educational attainment that ranges from 0=less than high school to 5=post-graduate degree. The pattern of coefficients is very similar to that for college graduation: substantial negative effects of being male and living without a father in adolescence, but no differential impacts of family structure by gender. The interaction effects are small relative to the male effects and are not significant at conventional levels.

In general, the evidence from the Add Health cohorts of young adults strongly suggests that, though being male and living in a household without a biological father in adolescence are negatively associated with educational attainment, young men do not appear to be differentially affected by father absence when we focus on long-term outcomes such as college graduation. There is some limited evidence that high school graduation, which is likely to be more directly affected than college graduation by grade school achievement and misbehavior, may be a hurdle for which father presence is more important for boys.

4.3. Other Adult Outcomes: Labor Market, Family, and Mental Health

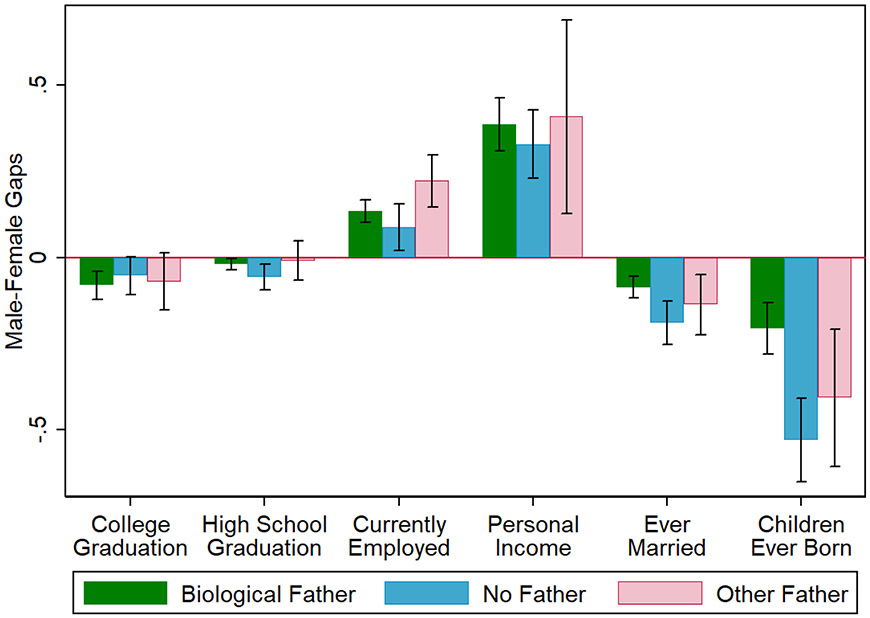

Gender gaps in key adult outcomes for different family structures are shown in Figure 2. Most gender gaps are prevalent across all types of family, though gaps for family outcomes appear to be larger for respondents who grew up in non-traditional families. Table 4 reports the estimated effects of father absence in adolescence on adult outcomes.

Figure 2: Gender Gaps in Adult Outcomes by Family Structures, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample.

Note: This figure displays the coefficient of “Male” dummy, when regressing the outcomes on “Male” dummy and a constant, with its 95% confidence interval. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “Currently Employed” is a dummy for whether is currently working at Wave IV. “Personal Income” is the total personal earnings before tax in 2006/2007/2008. “Ever Married” is a dummy for whether has been married up to Wave IV. “Children Ever Born” is the self-reported total number of child births up to Wave IV. All models are weighted by Wave IV weights.

Table 4:

Other Adult Outcomes, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Currently Employed |

Personal Income |

Number of Times Fired |

Job Satisfaction |

Financial Stress |

Ever Married |

Children Ever Born |

Depression Index |

| Male | 0.130*** (0.0167) |

14.71*** (1.505) |

0.332*** (0.0457) |

0.0118 (0.0294) |

−0.0117 (0.0141) |

−0.0988*** (0.0164) |

−0.215*** (0.0397) |

−0.106*** (0.0348) |

| Male*No Father | −0.0407 (0.0406) |

−1.970 (2.308) |

0.199 (0.121) |

−0.0205 (0.0765) |

−0.0564*

(0.0317) |

−0.103*** (0.0318) |

−0.333*** (0.0762) |

−0.0265 (0.0739) |

| Male*Other Father | 0.0930** (0.0390) |

1.785 (5.828) |

−0.0424 (0.117) |

0.0468 (0.0960) |

0.0328 (0.0500) |

−0.0493 (0.0444) |

−0.222** (0.0967) |

−0.274** (0.116) |

| No Father | −0.0208 (0.0253) |

−5.372*** (1.237) |

0.0719** (0.0336) |

−0.0679* (0.0391) |

0.140*** (0.0226) |

0.00727 (0.0230) |

0.306*** (0.0611) |

0.158*** (0.0493) |

| Other Father | −0.0624* (0.0339) |

−3.496 (2.462) |

0.103** (0.0502) |

−0.205*** (0.0633) |

0.0633** (0.0311) |

0.00555 (0.0348) |

0.231*** (0.0787) |

0.258*** (0.0935) |

| Constant | 0.401*** (0.141) |

−43.14*** (11.30) |

0.621* (0.355) |

3.489*** (0.253) |

0.451*** (0.124) |

−1.143*** (0.165) |

−1.071*** (0.332) |

0.152 (0.302) |

| Observations | 6,105 | 7,083 | 7,142 | 7,259 | 7,327 | 7,321 | 7,307 | 7,311 |

| R-squared | 0.046 | 0.062 | 0.026 | 0.005 | 0.038 | 0.073 | 0.109 | 0.025 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.788 | 36.060 | 0.467 | 3.909 | 0.216 | 0.560 | 0.847 | 0.010 |

| Mother’s characteristics | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors clustered by school.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “Currently Employed” is a dummy for whether is currently working at Wave IV. “Personal Income” is the total personal earnings before tax in 2006/2007/2008. “Number of Times Fired” is the total number of times being fired since 2001. “Job Satisfaction” is on 5 point scale. “Financial Stress” is a dummy for whether has met liquidity constraints in the past year. “Ever Married” is a dummy for whether has been married up to Wave IV. “Children Ever Born” is the self-reported total number of child births up to Wave IV. “Depression Index” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of 11 variables, a subset of 19 Wave I variables. Mothers characteristics include education and dummies for foreign-born and young mother (under 22). All models include birth cohort. All models are weighted by Wave IV weights.

In general, growing up in a father-absent or a step-father household is associated with negative labor market and other economic outcomes for both men and women, including employment, income, job satisfaction, job terminations, and a measure of financial stress (Columns (1)-(5)). For most of these outcomes, the effects do not differ significantly by gender. With the exception of number of times fired, the gender/father presence interaction terms are small and all are imprecisely estimated. One exception is that, though other father figures have a weakly negative association with the likelihood of being currently employed for women, this is not true for men: the stepfather-male interaction term is positive and significant at the 5% level. Also, the negative effect of a no-father household on financial stress is significantly smaller for men than for women. This evidence shows that the effects of non-traditional family structure on most labor market outcomes, as with educational attainment, do not differ across genders. When they do differ significantly, it is to the benefit of men rather than women.

Men typically marry at later ages than women, and we find that male Add Health respondents are less likely to have ever been married than female respondents at the same age (Column 6) and also report fewer children (Column 7). Marriage probabilities for women who grew up in father-absent and step-father households are not significantly different from those in bio-father households, but father absence is associated with a lower likelihood of being ever married for men. Gender differences also emerge for the number of reported children ever born: father absence and other father figures are significantly associated with more births for women and, since marriage probabilities remain unchanged, many of these are likely to be non-marital births. These positive effects are offset for men by the negative coefficients on the interaction terms, however, indicating that family background has no apparent effect on fertility for men. This reduction in marriage for men and increased fertility for women are generally consistent with Anderson (2017), who finds that adverse childhood environments are associated with increased sexual risk behaviors and greater likelihood of living in an unmarried couple for both men and women.

One possible mechanism for these effects on family dynamics is that non-traditional family structure in adolescence differentially changes the preferences and expectations about family formation and stability for boys and girls, and these gender differences persist into adulthood. An alternative explanation is that non-traditional family structure is associated with more negative marriage market characteristics, especially for men. Column (8), Table 1 provides some evidence that fails to support the former hypothesis. Although non-traditional family structure is negatively associated the Wave I reports regarding their chances of being married at age 25, the effects are not different across gender. Therefore, self-reports in adolescence do not indicate that the effects come from changes in marriage aspirations that differ between boys and girls. This is consistent with the findings of Kamp Dush, Arocho, Mernitz, and Bartholomew (2018), who attribute intergenerational correlations of partnering behaviors to the transmission of poor marriageable characteristics and relationship skills.18

Non-traditional family structure is associated with higher levels of depression in adulthood (Column 8). In addition, the association between step-father households and depression, which was positive for girls but not for boys in adolescence, appears to be a pattern that persists into adulthood.

The key takeaway from these analyses is that, though the absence of a biological father appears to have some persistent effects that differ by gender, particularly for family formation in adulthood, these effects do not fall readily into a vulnerable boys framework. There are few gendered effects on economic and labor market outcomes, but these tend to disadvantage women, and step-father families have a persistent association with depression in adulthood only for women.

4.4. School Quality and Neighborhood Effects

The “male vulnerability” hypothesis has been studied primarily in terms of adolescent responses to family disadvantage, but Autor et al. (2019) have also found that boys appear to be more sensitive than girls to variations in school quality and neighborhood characteristics in terms of test scores, absences, and suspensions, though these environmental factors explain only a small portion of the family SES contribution to this gap.

The estimates in Table 5 examine whether the short-run and long-run outcomes of male students in Add Health are more responsive to variations in school quality than are outcomes for female students. The school quality index is strongly associated with a lower probability of school suspension, higher educational aspirations, higher grades in adolescence, higher high school and college graduation rates, and lower fertility. For adolescent outcomes, some of the gender interaction effects are also significant. The gender gaps in the college attendance desires and expectations and in school suspensions are much smaller in high-quality schools. In other words, boys are indeed more responsive to school quality than girls in terms of educational aspirations and suspensions. However, as with father absence, these differential effects do not appear to have implications for eventual educational attainment, including high school and college graduation, employment, income and marriage. The only exception among adult outcomes is fertility: though the number of births by Wave IV is significantly reduced by higher school quality for women, the reported fertility of males is much less responsive to school quality.

Table 5:

School Quality Effects, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample

| Adolescent Outcomes | Adult Outcomes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |

| VARIABLES | School Problem Index |

Ever Suspended from School |

Depression Index |

Wants to Attend College |

Expects to Attend College |

English Grade |

Math Grade |

College Graduation |

High School Graduation |

Currently Employed |

Personal Income |

Ever Married |

Children Ever Born |

| Male | 0.212*** (0.0377) |

0.162*** (0.0157) |

−0.269*** (0.0332) |

−0.214*** (0.0400) |

−0.286*** (0.0361) |

−0.399*** (0.0375) |

−0.0687* (0.0392) |

−0.0901*** (0.0192) |

−0.0280*** (0.00676) |

0.118*** (0.0163) |

15.68*** (2.018) |

−0.122*** (0.0165) |

−0.272*** (0.0471) |

| Male*School Quality Index | −0.0168 (0.0315) |

−0.0319** (0.0154) |

−0.0150 (0.0330) |

0.0710* (0.0357) |

0.0860*** (0.0268) |

0.0386 (0.0359) |

0.0158 (0.0312) |

0.0106 (0.0167) |

0.0105 (0.00993) |

−0.00109 (0.0170) |

0.554 (2.006) |

−0.00398 (0.0184) |

0.0787** (0.0334) |

| School Quality Index | −0.0123 (0.0271) |

−0.0291** (0.0137) |

−0.0145 (0.0264) |

0.0560** (0.0267) |

0.0856*** (0.0250) |

0.0501* (0.0264) |

0.0787** (0.0361) |

0.0507** (0.0208) |

0.0177** (0.00803) |

0.0179 (0.0139) |

1.531 (1.247) |

0.00139 (0.0201) |

−0.108*** (0.0368) |

| Male*No Father | 0.186** (0.0926) |

0.0560* (0.0305) |

0.0236 (0.0775) |

−0.177** (0.0729) |

−0.0903 (0.0913) |

0.0312 (0.106) |

−0.138 (0.0888) |

0.0401 (0.0372) |

−0.0335 (0.0217) |

−0.0478 (0.0380) |

−1.219 (3.203) |

−0.0697* (0.0361) |

−0.298*** (0.0942) |

| Male*Other Father | 0.0969 (0.0962) |

0.0421 (0.0485) |

−0.279* (0.140) |

−0.0208 (0.0969) |

−0.0597 (0.106) |

−0.00570 (0.112) |

0.0331 (0.136) |

0.0350 (0.0464) |

−0.00407 (0.0347) |

0.0891* (0.0479) |

4.980 (8.544) |

−0.0160 (0.0523) |

−0.146 (0.109) |

| No Father | 0.158** (0.0618) |

0.117*** (0.0217) |

0.186*** (0.0576) |

−0.0439 (0.0635) |

−0.227*** (0.0716) |

−0.264*** (0.0624) |

−0.151** (0.0671) |

−0.132*** (0.0258) |

−0.0380*** (0.0122) |

−0.0186 (0.0301) |

−6.052*** (1.676) |

−0.0344 (0.0279) |

0.270*** (0.0734) |

| Other Father | 0.171* (0.0869) |

0.0563** (0.0262) |

0.390*** (0.128) |

0.00280 (0.0683) |

−0.125 (0.0840) |

−0.0948 (0.0750) |

−0.125 (0.114) |

−0.127*** (0.0269) |

−0.0374* (0.0206) |

−0.0981** (0.0383) |

−3.616 (3.411) |

−0.0187 (0.0419) |

0.193** (0.0899) |

| Constant | −0.456 (0.422) |

−0.345** (0.162) |

−1.031*** (0.299) |

0.870*** (0.315) |

−0.727** (0.305) |

2.516*** (0.403) |

3.077*** (0.594) |

0.0107 (0.173) |

0.616*** (0.110) |

0.483*** (0.128) |

−26.51 (16.87) |

−0.897*** (0.182) |

−0.827** (0.381) |

| Observations | 5,207 | 5,314 | 5,306 | 5,305 | 5,304 | 5,098 | 4,809 | 5,316 | 5,316 | 4,433 | 5,149 | 5,313 | 5,302 |

| R-squared | 0.039 | 0.137 | 0.057 | 0.103 | 0.168 | 0.085 | 0.030 | 0.163 | 0.094 | 0.042 | 0.054 | 0.055 | 0.114 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.034 | 0.224 | 0.053 | −0.048 | −0.026 | 2.882 | 2.746 | 0.376 | 0.943 | 0.803 | 37.741 | 0.590 | 0.880 |

| Mother’s characteristics | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note:Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors clustered by school.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “School Quality Index” is a standardized index based on school administrator reports of average daily attendance, class size, % of new and experienced teachers, % of teachers with a Masters degree, grade 12 dropout rates, % of students with achievement tests below and above grade level, and % of 12th graders enrolled in college next year. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “School problems” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A5. “Depression” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A6. Grades are student-reported and range from 1=D or lower to 4=A. College desires/expectations are standardized measures based on a 0-4 scale. “Currently Employed” is a dummy for whether is currently working at Wave IV. “Personal Income” is the total personal earnings before tax in 2006/2007/2008. “Ever Married” is a dummy for whether has been married up to Wave IV. “Children Ever Born” is the self-reported total number of child births up to Wave IV. Mothers characteristics include education and dummies for foreign-born and young mother (under 22). All models include birth cohort. Models (1)-(7) are weighted by Wave I weights and models (8)-(13) are weighted by Wave IV weights.

Table 6 investigates whether neighborhood effects are different across gender, for short-run and long-run outcomes. The proportion of highly-educated people in the neighborhood adolescents live in is strongly associated with fewer suspensions, higher educational aspirations, and higher math grades in adolescence, and with higher high school and college graduation rates, higher income, higher employment probabilities, lower probabilities of marriage, and fewer births in adulthood. In adolescence, the educational aspirations of boys are significantly more responsive to neighborhood quality than those of girls. There is also some evidence that the relative math grades of girls are higher in highly-educated neighborhoods. These results indicate that a highly-educated neighborhood boosts the aspirations for higher education for boys relative to girls, but improves the math performance of girls relative to boys. These differential neighborhood effects don’t persist into adulthood for college graduation, employment, income and marriage, but there is some evidence that an educated neighborhood benefits boys more than girls in terms of high school graduation. In addition, the fertility decisions of men are less responsive to neighborhood quality than women’s, as is the case with school quality effects.

Table 6:

Neighborhood Effects, Add Health Non-Hispanic White Sample

| Adolescent Outcomes | Adult Outcomes | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) | (13) | |

| VARIABLES | School Problem Index |

Ever Suspended from School |

Depression Index |

Wants to Attend College |

Expects to Attend College |

English Grade |

Math Grade |

College Graduation |

High School Graduation |

Currently Employed |

Personal Income |

Ever Married |

Children Ever Born |

| Male | 0.209*** (0.0759) |

0.129*** (0.0254) |

−0.228*** (0.0662) |

−0.234*** (0.0596) |

−0.300*** (0.0566) |

−0.356*** (0.0565) |

−0.00300 (0.0703) |

−0.0664*** (0.0245) |

−0.0426*** (0.0159) |

0.160*** (0.0271) |

12.24*** (2.118) |

−0.0856*** (0.0301) |

−0.408*** (0.0617) |

| Male*Educated Neighborhood | 0.220 (0.270) |

0.0204 (0.0732) |

−0.0379 (0.250) |

0.395** (0.169) |

0.372** (0.151) |

−0.0117 (0.178) |

−0.363* (0.196) |

−0.0827 (0.0845) |

0.0800* (0.0435) |

−0.109 (0.0942) |

10.31 (8.431) |

−0.0588 (0.0942) |

0.762*** (0.169) |

| Educated Neighborhood | 0.0137 (0.180) |

−0.183*** (0.0617) |

−0.0867 (0.184) |

0.444*** (0.108) |

0.705*** (0.109) |

0.232 (0.180) |

0.425** (0.191) |

0.625*** (0.0779) |

0.0487* (0.0286) |

0.218*** (0.0830) |

16.87*** (5.335) |

−0.323*** (0.0809) |

−1.420*** (0.152) |

| Male*No Father | 0.178** (0.0798) |

0.0807*** (0.0280) |

−0.00548 (0.0667) |

−0.150** (0.0659) |

−0.105 (0.0749) |

0.00881 (0.0791) |

−0.0491 (0.0726) |

0.0269 (0.0286) |

−0.0300 (0.0197) |

−0.0477 (0.0402) |

−2.020 (2.250) |

−0.0993*** (0.0315) |

−0.305*** (0.0756) |

| Male*Other Father | 0.0433 (0.0908) |

0.0747** (0.0366) |

−0.210* (0.114) |

−0.125 (0.102) |

−0.117 (0.105) |

−0.0137 (0.0974) |

0.0554 (0.118) |

0.0172 (0.0395) |

0.0117 (0.0270) |

0.0869** (0.0396) |

1.430 (5.775) |

−0.0433 (0.0432) |

−0.177* (0.0957) |

| No Father | 0.176*** (0.0575) |

0.0989*** (0.0194) |

0.186*** (0.0493) |

2.74e-05 (0.0484) |

−0.155*** (0.0535) |

−0.236*** (0.0541) |

−0.183*** (0.0520) |

−0.134*** (0.0212) |

−0.0319** (0.0131) |

−0.0185 (0.0254) |

−5.005*** (1.226) |

0.00176 (0.0229) |

0.268*** (0.0630) |

| Other Father | 0.147** (0.0703) |

0.0326* (0.0191) |

0.277*** (0.0973) |

0.0337 (0.0623) |

−0.0423 (0.0781) |

−0.0671 (0.0654) |

−0.129 (0.0889) |

−0.114*** (0.0270) |

−0.0326* (0.0175) |

−0.0618* (0.0343) |

−3.401 (2.492) |

0.00339 (0.0351) |

0.203** (0.0800) |

| Constant | −1.041*** (0.348) |

−0.468*** (0.142) |

−1.608*** (0.253) |

1.362*** (0.254) |

−0.00826 (0.266) |

3.425*** (0.332) |

3.833*** (0.376) |

−0.235 (0.161) |

0.611*** (0.0793) |

0.336** (0.138) |

−46.72*** (10.98) |

−1.091*** (0.161) |

−0.809** (0.319) |

| Observations | 7,142 | 7,262 | 7,248 | 7,246 | 7,245 | 7,008 | 6,702 | 7,264 | 7,264 | 6,049 | 7,025 | 7,258 | 7,244 |

| R-squared | 0.050 | 0.124 | 0.063 | 0.097 | 0.150 | 0.093 | 0.040 | 0.194 | 0.079 | 0.051 | 0.067 | 0.081 | 0.125 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.000 | 0.206 | −0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 2.918 | 2.790 | 0.369 | 0.935 | 0.788 | 36.100 | 0.560 | 0.844 |

| Mother’s characteristics | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses. Standard errors clustered by school.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “Educated Neighborhood” is the proportion of aged 25+ individuals with college degree or more at census tract level. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at Wave I. “School problems” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A5. “Depression” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of the variables in Table A6. Grades are student-reported and range from 1=D or lower to 4=A. College desires/expectations are standardized measures based on a 0-4 scale. “Currently Employed” is a dummy for whether is currently working at Wave IV. “Personal Income” is the total personal earnings before tax in 2006/2007/2008. “Ever Married” is a dummy for whether has been married up to Wave IV. “Children Ever Born” is the self-reported total number of child births up to Wave IV. Mothers characteristics include education and dummies for foreign-born and young mother (under 22). All models include birth cohort. Models (1)-(7) are weighted by Wave I weights and models (8)-(13) are weighted by Wave IV weights.

Table A9 presents results from models that include both school quality and neighborhood effects. The results are robust, implying that although school quality and neighborhood education levels are correlated, they have different patterns of effects. In general, school quality and neighborhood effects on some adolescent outcomes, especially educational aspirations, suspension and math grades, differ across genders, implying that boys are more responsive to advantages/disadvantages in adolescence. However, as with father absence, the differential effects vanish in adulthood, except for fertility decisions.19

4.5. Additional Results

4.5.1. Add Health Black Sample

The African-American sample in Add Health is much smaller than the non-Hispanic white sample (about 2700 vs. 7200), but the higher prevalence of non-traditional families in this population makes a parallel analysis of key outcomes on this subsample potentially informative. On some dimensions, the results reported in Table A10 contrast sharply with those from the majority sub-sample. Young Black men are less likely to graduate from high school or college than young Black women (and by larger margins than in the white sample) and no-father households are still associated with less education, more school problems, and a higher probability of school suspension. However, in important departures from the white sample results, there are no significant gender or family structure effects on college aspirations, and no family structure effects on the depression index. There is only one significant gender/family structure interaction, and it is a surprising one. The gender gap in school suspensions is smaller for adolescents in no-father families, rather than larger. In general, school discipline rates are much higher for Black students, male and female, and the behavioral determinants appear to be very different as well. The differences between the Black and white samples on this dimension may be reflective of racial differences in the institutions of school discipline.

4.5.2. NLSY97 White Non-Hispanic Sample

In order to examine the external validity of our results, we replicate the main analysis using another representative longitudinal dataset, NLSY97. The results for adult outcomes are reported in Table 7. Most results are consistent with those from the Add Health sample. Father absence has no differential effect on high school and college graduation, personal income and job satisfaction for NLSY97 men and women. Step-father households, in one departure from the Add Health results, have less negative impacts on college graduation for men than for women, though they do have a marginally significant negative effect on the job satisfaction of men compared to women. Non-traditional family structures tend to increase the likelihood of being currently employed for men relative to women and to decrease the likelihood of being ever married and fertility more for men, as in Add Health. In addition, there is some evidence that other father figures increase depression in adulthood less for males relative to females, which is also consistent with the Add Health results. Table A11 reports estimates using alternative measures of educational attainment, and these results also support the robustness of our Add Health findings. In general, the results using NLSY97 sample support a conclusion that non-traditional family structures have few differential impacts on educational attainment across gender and any significant effects tend to be in favor of males rather than females. This implies that the apparent excess vulnerability of adolescent boys in school-based behaviors doesn’t persist into adulthood.

Table 7:

Educational Attainment and Other Adult Outcomes, NLSY97 Non-Hispanic White Sample

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | College Graduation |

High School Graduation |

Currently Employed |

Personal Income |

Job Satisfaction |

Ever Married |

Children Ever Born |

Depression Index |

| Male | −0.113*** (0.0205) |

−0.0151** (0.00721) |

0.0839*** (0.0149) |

15.61*** (1.972) |

−0.0499 (0.0485) |

−0.110*** (0.0211) |

−0.284*** (0.0529) |

−0.230*** (0.0479) |

| Male*No Father | 0.0142 (0.0391) |

0.00722 (0.0236) |

0.0920*** (0.0324) |

0.121 (3.652) |

−0.113 (0.106) |

−0.0420 (0.0449) |

−0.371*** (0.121) |

−0.0474 (0.106) |

| Male*Other Father | 0.0758* (0.0410) |

0.0372 (0.0308) |

−0.00616 (0.0456) |

0.407 (4.221) |

−0.212* (0.119) |

−0.117** (0.0507) |

−0.307** (0.139) |

−0.242* (0.124) |

| No Father | −0.205*** (0.0276) |

−0.0524*** (0.0155) |

−0.0777*** (0.0269) |

−9.143*** (2.148) |

−0.0256 (0.0753) |

−0.0297 (0.0297) |

0.338*** (0.0887) |

0.143* (0.0769) |

| Other Father | −0.250*** (0.0304) |

−0.0797*** (0.0224) |

−0.0591 (0.0365) |

−9.286*** (2.718) |

0.116 (0.0874) |

0.0345 (0.0344) |

0.248** (0.109) |

0.326*** (0.0910) |

| Constant | −0.155* (0.0916) |

0.794*** (0.0531) |

0.689*** (0.0834) |

−9.435 (9.518) |

4.004*** (0.251) |

0.339*** (0.103) |

1.324*** (0.270) |

0.0852 (0.249) |

| Observations | 2,998 | 2,998 | 2,989 | 2,533 | 2,363 | 2,991 | 2,994 | 2,902 |

| R-squared | 0.224 | 0.059 | 0.043 | 0.091 | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.095 | 0.032 |

| Mean of dependent variable | 0.400 | 0.949 | 0.853 | 49.933 | 4.129 | 0.647 | 1.268 | 0.025 |

| Mother’s characteristics | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses.

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1. “No Father” and “Other Father” refer to living arrangements at baseline survey (1997). “Currently Employed” is a dummy for whether is currently working at round 17 survey. “Personal Income” is the total personal earnings before tax in 2014. “Job Satisfaction” is on 5 point scale. “Ever Married” is a dummy for whether has been married up to round 17 survey. “Children Ever Born” is the self-reported total number of child births up to round 17 survey. “Depression Index” is a standardized index based on factor analysis of 5 variables. Mothers characteristics include education and mother’s age when the first child in the household and the respondent was/were born. All models include birth cohort. All models are weighted by round 17 sample weights.

5. Conclusion

Using data on young cohorts of men and women from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, we investigate the association between economic disadvantage in adolescence and relative outcomes for men and women, both in school and later in life. Girls appear more resilient to father absence when the outcomes are adolescent school problems, suspensions, and educational aspirations, while boys appear more resilient to father absence when we examine depression. Though these school-age outcomes are themselves associated with poor educational and labor market outcomes in adulthood, these gender gaps related to father absence do not result in differential college graduation rates, income or other adult economic outcomes. The principal exceptions are marriage and reported fertility: non-traditional family structures are associated with lower relative probabilities of marriage and number of children for men, compared to women. The pattern of results is similar when boy/girl vulnerability to poor school quality or less educated neighborhoods, instead of father absence, is examined. Additional results using another representative longitudinal dataset, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997, show very similar patterns as well. Null results are an important component of our findings but, with few exceptions, we can rule out substantial levels of excess male vulnerability in adult economic outcomes.

These mixed results—gender-specific behavioral responses to family disadvantage among school children that do not result in gendered consequences for eventual educational attainment and other economic outcomes—suggest that previous findings of excess male vulnerability, while provocative and interesting, can be over-interpreted. Measures of problem behaviors in school seem to reflect gendered responses to disadvantage and they do not have clear implications for actual skill development in boys and girls or for eventual educational outcomes. Behavior in school is a consequence, not just of underlying skills and traits, but also of constraints and expectations that operate very differently for boys and girls due to gender norms in behavior on the part of parents, teachers, and the children themselves. Externalizing behavior that leads to problems in school is much more prevalent among boys, while internalizing behavior, which includes anxiety and depression, is a more common response to stress for girls, but is not included in the survey and administrative data used in prior studies. Most of the socio-behavioral outcomes examined in other studies, such as kindergarten readiness and school suspensions, are also related to externalizing behavior and so suggest greater male vulnerability to disadvantage. This analysis of Add Health data, though consistent with these earlier studies, finds no empirical support for the hypothesis that disadvantages in adolescence have contributed to the growing gender gap in college graduation, or to gender gaps in other adult economic outcomes.

Appendix

A. Data Appendix: Description of NLSY97 Sample

NLSY97 is a representative longitudinal study with surveys from 1997 (round 1) to 2015-2016 (round 17). The cohort was born between 1980 and 1984, with respondents aged between 12 and 18 at the time of the first interview and between 30 and 36 at round 17. 8,984 individuals were initially interviewed in round 1. Nearly 80 percent (7,103) of the round 1 sample were interviewed in round 17. Consistent with Add Health sample, we uses subsamples of 1,486 non-Hispanic white women and 1,515 non-Hispanic white men who lived with their biological mother in round 1 survey. Table A3 shows summary statistics of important variables in both Add Health sample and NLSY97 sample. For most of the characteristics, these two samples are comparable.

A.1. Adult Outcomes

The round 17 interview collected an array of adult outcomes, including educational attainment, marriage, number of births, employment, income and depression.

-