Abstract

Objective

Although tinnitus is one of the most commonly reported symptoms in the general population, patients with bothersome tinnitus are challenged by issues related to accessibility of care and intervention options that lack strong evidence to support their use. Therefore, creative ways of delivering evidence-based interventions are necessary. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT) demonstrates potential as a means of delivering this support but is not currently available in the United States. This article discusses the adaptation of an ICBT intervention, originally used in Sweden, Germany, and the United Kingdom, for delivery in the United States. The aim of this study was to (a) modify the web platform's features to suit a U.S. population, (b) adapt its functionality to comply with regulatory aspects, and (c) evaluate the credibility and acceptability of the ICBT intervention from the perspective of health care professionals and patients with bothersome tinnitus.

Materials/Method

Initially, the iTerapi ePlatform developed in Sweden was adopted for use in the United States. Functional adaptations followed to ensure that the platform's functional and security features complied with both institutional and governmental regulations and that it was suitable for a U.S. population. Following these adaptations, credibility and acceptance of the materials were evaluated by both health care professionals (n = 11) and patients with bothersome tinnitus (n = 8).

Results

Software safety and compliance regulatory assessments were met. Health care professionals and patients reported favorable acceptance and satisfaction ratings regarding the content, suitability, presentation, usability, and exercises provided in the ICBT platform. Modifications to the features and functionality of the platform were made according to user feedback.

Conclusions

Ensuring that the ePlatform employed the appropriate features and functionalities for the intended population was essential to developing the Internet-based interventions. The favorable user evaluations indicated that the intervention materials were appropriate for the tinnitus population in the United States.

Various chronic conditions require both medical interventions and self-management to reduce negative consequences and to improve quality of life for individuals living with these conditions (Grady & Gough, 2014). Tinnitus is one such chronic symptom for which there is no known cure. The focus of tinnitus management may be medical, such as the use of pharmaceuticals; audiological, which emphasizes sound enrichment; or psychological, which may include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Indeed, the approach with the most evidence of effectiveness in reducing tinnitus distress at present is the use of CBT (Hesser et al., 2011; Hoare et al., 2011). Its effectiveness is attributed to CBT's focus on facilitating accurate interpretations of the tinnitus event, as well as enhancing various coping strategies, thereby helping individuals manage their reactions to tinnitus (Andersson, 2002; Cima et al., 2014; Henry & Wilson, 2001).

Often, patients with bothersome tinnitus do not have access to such evidence-based interventions. As a result, they may develop negative reactions to and behaviors associated with hearing tinnitus, which can lead to additional difficulties such as associated anxiety, isolation, depression, and insomnia (Beukes, Baguley, et al., 2018; Martz & Henry, 2016). Therefore, it is essential for those with chronic tinnitus to have access to interventions that promote positive coping behaviors and teach strategies for self-management of tinnitus. Historically, the majority of tinnitus interventions were delivered using face-to-face care (D. M. Thompson et al., 2017). To increase the reach of these interventions, Internet-based provision of CBT (known as ICBT) was tested, with success, in several countries including Sweden, Germany, and the United Kingdom (Andersson et al., 2002; Beukes, Baguley, et al., 2018; Beukes, Andersson, et al., 2018; Weise et al., 2016). Such interventions promoted self-management in patients with bothersome tinnitus and were delivered with and without the support of clinicians. A systematic review and meta-analysis (Beukes et al., 2019) identified that tinnitus Internet interventions were effective interventions in reducing tinnitus distress and other associated difficulties (e.g., anxiety, depression, insomnia). Results are commensurate with those from face-to-face clinical care (Beukes, Andersson, et al., 2018). Such results indicate the potential of digital technologies to provide evidence-based care for individuals with bothersome tinnitus when provision of tinnitus therapies is limited.

Despite the strong evidence base regarding CBT for tinnitus, CBT is rarely provided to patients. A large-scale epidemiological survey (n = 75,764) in the United States suggests that nearly half of the individuals (49.4%) with tinnitus discuss their tinnitus with their physicians (Bhatt et al., 2016). The study results suggest that medication, which has the weakest evidence base for tinnitus management, is the most frequently recommended management option (i.e., 45.5%) and CBT, which has the most evidence for tinnitus management, is the least recommended management option (i.e., 0.2%). This may be partly associated with the lack of provision of tinnitus CBT interventions in the United States, a finding that reinforces the great need for accessible evidence-based tinnitus interventions for the U.S. population. An ICBT intervention may well serve this population due to the large geographical area and low audiologist/patient ratio in certain regions. Although ICBT is available, its most recent application for patients with tinnitus is adapted for a U.K. population (Beukes et al., 2016); modifications of such an intervention would be required to ensure its suitability for use in the United States. Modifications should ensure security regulations are met and that the intervention is appropriate for the population of interest. Adaptations can include language and terminology used in the intervention as well as the features and functionality of the ePlatform used when delivering the intervention. The intervention also must comply with the institutional, local, regional (state), and national regulations (e.g., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act [HIPAA]).

The aim of this study was to adapt ICBT to ensure the platform and its implementation met regulatory standards in the United States. A further aim was to evaluate the credibility and acceptability of the ICBT program from the perspective of health care professionals and patients with bothersome tinnitus. Confirming acceptability was required before undertaking clinical trials investigating the efficacy of such an intervention.

Method

Study Design

This study design was composed of three phases: (a) to identify the key features of the intervention to include for a U.S. population, (b) to adapt the ePlatform to comply with U.S. institutional and governmental regulations, and (c) to obtain end-user credibility and acceptability ratings regarding the intervention and the ePlatform. Ethical approval (IRB-FY17-209) was obtained from the institutional review board at Lamar University, Beaumont, TX.

Participants

Purposeful sampling was used to recruit participants for each phase according to their expertise and suitability as follows:

Phase 1: Tinnitus practitioners and researchers were approached to be part of a steering group. The purpose of this steering group was to identify the features and functions of the ePlatform from a user-centric perspective to address its appropriateness for the U.S. population. The group consisted of two psychologists and three audiologists working with patients with tinnitus and two patients with bothersome tinnitus. Physicians were not included in the expert group as they were unlikely to be involved in the psychological therapies and might not be familiar with the use of CBT for patients with bothersome tinnitus.

Phase 2: Two software engineers with expertise in security features were assigned to be involved in adjusting the ePlatform features to ensure compliance with regulations.

Phase 3: Health care professionals (n = 20 invited) and patients with bothersome tinnitus (n = 15 invited) were asked to evaluate the credibility and acceptance of the materials. To ensure a range of views, the health care professionals recruited included audiologists, psychologists, tinnitus researchers, and tinnitus support workers. To ensure different cultural views were included, both Spanish and English professionals and patients with tinnitus were approached.

Phase 1: Identification of Key Features and Functionalities of ICBT

Identifying the most appropriate theoretical base and specific intervention for this study was initially undertaken by considering the various programs available in the United States. The ICBT intervention selected for use for a U.S. population was that originally developed for a Swedish population (Andersson et al., 2002) and later updated by Andersson and Kaldo-Sandström (2003) and Kaldo et al. (2007), to address the growing evidence backing this program (e.g., Beukes, Andersson, et al., 2018; Weise et al., 2016). The program was furthermore available in multiple languages having already been translated to English (Abbott et al., 2009) and German (Jasper et al., 2014). Additional updates were implemented, such as adapting the English version into a more interactive version (Beukes et al., 2016). However, in order to ensure its suitability to the U.S. population, the program required further modifications. Adaptations were based on intervention design principles outlined by Beukes et al. (2016), including the following:

Involving a multidisciplinary team in deciding the content.

Updating the evidence-based content of the program to ensure its relevance.

Ensuring the comprehensiveness of materials provided, including tailored materials to suit individual patient needs.

Incorporating interactive elements to encourage user engagement, facilitate participation, promote self-management, enhance self-efficacy, and initiate behavior change.

Ensuring a user-friendly, uncluttered design to minimize technological barriers that might increase anxiety.

Incorporating a user-centric approach by accommodating different learning styles and cultural adaptations for a U.S. population. These included adding more video explanations and instructions and sharing relevant additional resources such as smartphone applications.

Phase 2: ePlatform Adaptation

Initially, the most appropriate ePlatform for this study had to be identified requiring features and functionalities of various platforms be considered and compared. The ePlatform “iTerapi,” originally developed in Sweden, was selected for this project as its specific features (see Beukes et al., 2016) and security measures best met the needs for this project (see Vlaescu et al., 2016). Furthermore, this platform was well tested and used in more than 100 behavior intervention trials across the globe.

Following selection, the platform required adaptation to ensure that the security components complied with both institutional and governmental regulations and met the regulations outlined by the HIPAA of 1996. HIPAA compliance requires implementation of three types of safeguards: (a) administrative, (b) physical, and (c) technical. Finally, functional modifications were made to customize the platform features for a U.S. tinnitus population.

Phase 3: User Credibility and Acceptability Evaluation

The study design for this phase consisted of an independent-measures research design that established user evaluation of the ICBT content and iTerapi platform. The main goal of this step was to determine whether the treatment materials and the ePlatform were appropriate for the U.S. tinnitus population from the perspectives of patients and health care professionals whose practices included tinnitus management. Study participants were recruited using a mixture of purposeful and convenience sampling methods. Participants who volunteered and consented were provided full access to the intervention and its interactive elements. Thirty-five participants (20 health care professionals and 15 patients with bothersome tinnitus) were recruited from the Lamar University Audiology Clinic and also via the American Tinnitus Association. No specific criteria were used in recruiting patients with tinnitus, although efforts were made to recruit health care professionals with different background and work experience in the area of tinnitus management. Only 26 of the 35 invited responded to the e-mail, agreed to participate in the study, and were given access to the ICBT program. However, only 19 participants (11 health care professionals and eight patients with bothersome tinnitus) examined the intervention materials and completed the questionnaires.

Access to all the modules was provided at the same time. Brief instructions were provided regarding the intervention tasks and expectations from the study participants. They were instructed to familiarize themselves with the ICBT program and the iTerapi ePlatform and spend as much time as possible evaluating the program features. Participants had a 2-month period to complete the intervention evaluation. The evaluation was a 15-item questionnaire, which was developed by Beukes et al. (2016) to specifically evaluate online interventions. This measure was designed to consider the suitability, content, usability, presentation, and exercises offered by online interventions. The response scale included a 5-point Likert scale, with low to high rating, upon which 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. In addition, four open-ended questions were posed regarding the best aspects of the intervention, how much time was spent on each module, what elements required attention, and participant suggestions for further development. Completing the questions was optional for all participants.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Software Version 24.0. The descriptive statistics were used to identify sample characteristics such as gender and age. Continuous variables were summarized with means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were described using frequencies and percentages. When ordinal data (the individual Likert scale questions) were present, the median was reported. When the scores from questions were combined (total scores), the mean scores were reported. The distribution of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and normality plots. As the assumption of normality was violated, Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare usability ratings of health professionals and patients with bothersome tinnitus. A p value of .05 was considered statistically significant.

Analysis of the free-text responses was undertaken using a thematic analysis framework (Clarke et al., 2015). Individual statements were coded, and similar codes were grouped into themes. The coverage was calculated by counting the number of times the theme appeared in relation to the total number of free-text comments (with a maximum ratio of 1.0). To verify the themes selected, the coverage of each theme was identified to ensure it was substantial enough to be reported. Themes with a low coverage (below 0.1) were excluded due to lack of sufficient relevance to be reported. The coverage of that theme (the number of times the codes associated with that theme appeared in the free-text comments) was calculated with a maximum possible coverage value being 1.0 (all free-text comments are grouped within this one theme). Themes with a coverage below 0.1 suggest lack of sufficient relevance is not reported.

Results

Phase 1: ICBT Key Feature Identification

Adaptations of the program were identified by consulting the multidisciplinary team. The modifications made are listed and discussed hereinafter.

Updating the Evidence-Based Content

A new module on “mindfulness meditation” was added due to the emerging evidence base supporting this as an effective method of managing tinnitus (McKenna et al., 2018). Additional sections such as “research focus” segments were added to share research evidence with participants, which was hoped, would improve participant motivation.

Ensuring the Comprehensiveness and Tailoring the Materials to Suit Individual Needs

The multidisciplinary team included experts in tinnitus management who went through the program, modified the content for comprehensiveness, and identified instances in which tailoring was required. The final program consisted of 22 modules, of which five were optional (see Table 1). It was determined that running the program over an 8-week period should provide adequate time for participants to explore the broad range of topics. Modules were carefully organized in a logical order that started with an overview, followed by simple and important concepts, and subsequently introducing strategies the participants could work through on their own.

Table 1.

The comprehensive nature of the Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention offered.

| Modules | Week | Content | Video | Short worksheets or quizzes | Intervention load |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading time | Daily practicing | |||||

| 1 | 1 | Program rationale and outline | 1 | 3 | 15 min | Setting goals |

| 2 | 1 | Tinnitus overview | 1 | 4 | 15 min | Reading the module |

| 3 | 1 | Deep relaxation | 2 | 3 | 15 min | Twice a day for 10–15 min |

| 4 | 2 | Positive imagery | 1 | 5 | 10 min | Twice a day for 5 min |

| 5 | 2 | Deep breathing | 1 | 5 | 10 min | Twice a day for 5 min |

| 6 | 3 | Changing views | 0 | 7 | 10 min | Once a day for 5 min |

| 7 | 3 | Entire body relaxation | 1 | 3 | 10 min | Twice a day for 5 min |

| 18 | 3 | Sound enrichment a | 1 | 2 | 10 min | As required |

| 8 | 4 | Shifting focus | 0 | 3 | 10 min | 4 times a day for 2 min |

| 9 | 4 | Frequent relaxation | 1 | 3 | 10 min | 5–10 times, 1–2 min |

| 19 | 4 | Sleep guidelines a | 1 | 7 | 15 min | Implement daily |

| 10 | 5 | Thinking patterns | 0 | 4 | 15 min | 3 times a week for 10 min |

| 11 | 5 | Quick relaxation | 1 | 3 | 10 min | 7–15 times a day for up to 1 min |

| 20 | 5 | Improving focus a | 1 | 2 | 10 min | As required |

| 12 | 6 | Challenging thoughts | 1 | 3 | 15 min | 4 times a week for 5 min |

| 13 | 6 | Relaxation routine | 0 | 2 | 10 min | Deep relaxation twice a week; frequent relation 8 times a day; rapid relaxation during, before, or after difficult situations |

| 21 | 6 | Sound tolerance a | 1 | 4 | 15 min | As required, 1–2 min and increasing |

| 14 | 7 | Being mindful | 1 | 2 | 10 min | 2–5 times a day during normal activities |

| 22 | 7 | Listening tips a | 1 | 2 | 15 min | As required |

| 15 | 8 | Listening to tinnitus | 0 | 3 | 10 min | Once a day |

| 16 | 8 | Key point summary | 0 | 0 | 15 min | Reading the module |

| 17 | 8 | Future planning | 0 | 4 | 15 min | Future plan |

Note. The order of the modules is designed to use prior learning to later modules, for example, need to master deep relaxation before being able to do quick relaxation.

Optional module.

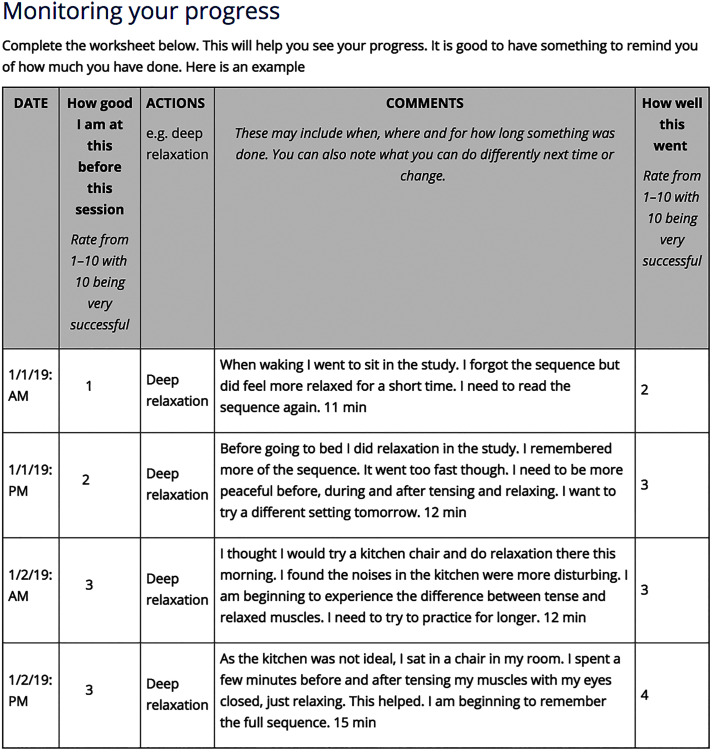

Adding Interactive Elements

The ICBT modules included text, images, videos, and exercises that encouraged user engagement as they ensured an interactive intervention was offered. The ICBT content and exercises were modified to facilitate behavior change in the novel population and were based on the Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour (Michie et al., 2011; L. M. Thompson et al., 2018). The worksheets were also revised; for example, one change added a worksheet that would serve as a record for daily practice, instead of different worksheets for different practice exercises. To promote behavioral change, a section on goal setting and monitoring for the program was included. In addition, a short survey to evaluate the most relevant modules for each user was also included.

Minimizing Technological Barriers

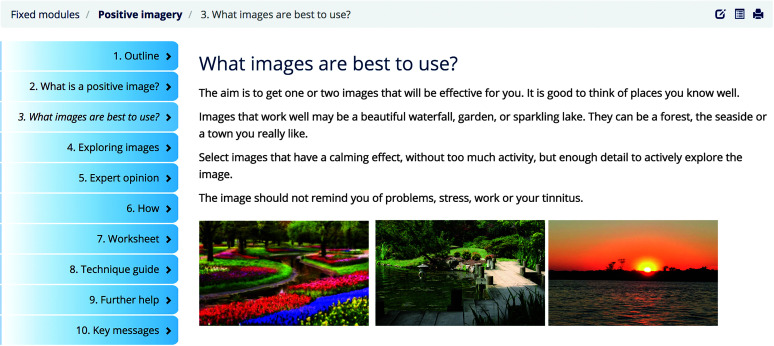

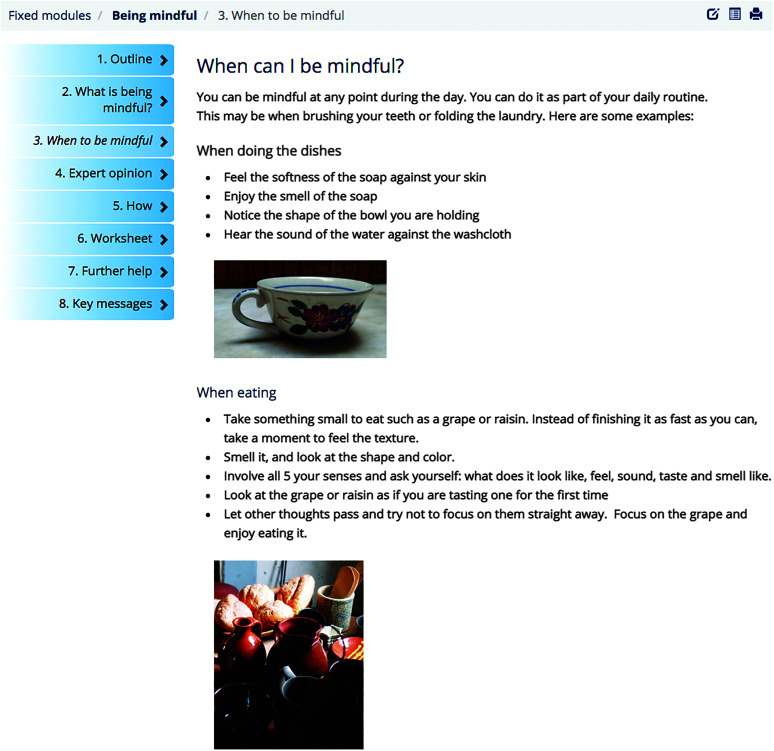

To ensure the intervention enabled behavior change and was not a barrier, possible technological barriers were identified. Ease of navigation was prioritized by incorporating user-friendly features; worksheets and processes were simplified. The design that had the calming background and used in the United Kingdom was selected. Images most appropriate for a U.S. population were included such as photos of familiar U.S. landscapes. Technological barriers were further reduced by simplifying the language that was used to ensure it was below the sixth reading grade level (Beukes et al., 2020). Figures 1 –3 provide examples of the intervention layout and worksheets.

Figure 1.

Example of an Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention layout.

Figure 2.

Example of an Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention material.

Figure 3.

Example of a worksheet.

Incorporating a User-Centric Approach

To accommodate this specific population, cultural and linguistic adaptations were made by using word substitutions, changing examples, and modifying the spelling of certain words (see Beukes et al., 2020). When making cultural adaptations, it was necessary to consider aspects relevant to the general population as well as the population of interest (i.e., patients with tinnitus) to ensure that the intervention was appropriate for the targeted culture (Heim & Kohrt, 2019). For this intervention, cultural adaptation included matching the materials with the ethnic, cultural, and social contexts of the population. Adaptations included modifying the language and examples used to support compatibility with the U.S. cultural expectations and meanings (for more details, see Beukes et al., 2020). Spelling and use of words that were unfamiliar or less commonly used in the United States were modified to support participant engagement. In addition, intervention materials and outcome measures were translated into Spanish and cross-checked to improve accessibility for the Spanish-speaking population (Beukes et al., 2020; Manchaiah et al., 2020). To accommodate auditory and visual learners, video explanations were added to each module. In addition, an animated video was also added to the study home pages to encourage engagement for those who preferred obtaining information about the study visually. This video included information about the study purpose and intervention design in a way that was easily understandable for the general population.

Phase 2: ePlatform Adaptation

Security Feature Modifications

To ensure the ePlatform was compliant with HIPAA regulations and functionally suitable for a U.S. population, the following steps were undertaken: First, the location of the ePlatform required consideration. The iTerapi ePlatform software is installed at the Linköping University server and provides international researchers access to software to run their clinical trials, but under the U.S. law (i.e., HIPAA), health care providers and their business associates are legally accountable for securing the privacy of patient data. Hence, it was deemed appropriate to store the study data within the U.S. institution leading the study. In order to achieve this, special permission was required to have a copy of the iTerapi software installed on the Lamar University server. A software licensing agreement was established between Linköping University (Sweden) and Lamar University (United States). The agreement was reviewed by the researchers, the IT team, and legal departments at both universities.

The next step was to ensure the iTerapi ePlatform met institutional and governmental compliance specifications for use in the United States. The platform was selected due to its superior inbuilt security features as detailed by Vlaescu et al. (2016). These features were assessed and modified where required, by ensuring compliance against HIPAA specifications by assessing the physical infrastructure and the software systems as follows:

Administrative safeguarding: IT technicians at the university ensured that the hardware equipment (servers and network) were constantly running. Redundancy was implemented by having multiple hardware backups to ensure continuity if one system failed. Full software backups were created daily, stored in a different building from the live servers, and were encrypted with a key that only two administrators could access.

Physical safeguarding: Physical safeguarding was ensured by storing the data within the Lamar University data center infrastructure. The Lamar University data center maintains the data with standard IT physical security controls and restricts access to only authorized personnel. The data in the server are fully encrypted, and two levels of encrypted backups are stored elsewhere within the University in separate locations. Moreover, another backup copy is stored in a geographically separate location.

Technical safeguarding: The information in the database was encrypted using AES-256 algorithms. This ensured that a relationship between the encrypted data on the platform and individual users was not possible by simply accessing the database. Moreover, the workstations of therapists were secured with malware and encryption software.

Functional Modifications

The most appropriate features of the platform were sought for the study participants. In-depth discussions between the selected team of experts identified the features and functions of the ePlatform from a user-centric perspective to ensure its appropriateness for the U.S. population. For instance, although there was the option of adding an open discussion forum, in which participants could interact, this feature was not activated. The omission was intended to prevent the possibility of negative thoughts or comments from one participant triggering negative thoughts in other participants. Mixed reactions to such an online forum were reported from users undertaking a Tinnitus E-Program (Greenwell et al., 2019).

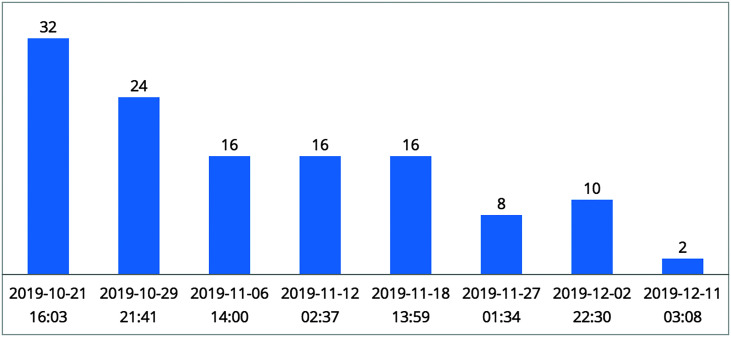

Table 2 provides details of features and functions selected for the U.S. population. The ePlatform was accessed via the public page (Tackling Tinnitus, 2020) by both study participants and therapists. Whereas the information in the public page was accessible to anyone, the access to intervention and other facilities was only available to study participants who completed the screening process and were enrolled in the study. Study participants accessed specific features, whereas the therapist (or administrator) had their own set of additional features. Figure 4 provides an example of a progress bar graph regarding weekly tinnitus distress.

Table 2.

ePlatform functionalities specific to Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy program in the United States.

| Functionality | Rationale and description |

|---|---|

| Functionalities for users | |

| Public page | Public page serves as a gateway to the ePlatform (i.e., www.tacklingtinnitus.org). Both therapists and users can log in to the ePlatform, but only through the public page. Anyone can access the public page, which provides detailed information about the program including the project aims, inclusion and exclusion criteria, reference to previous studies, and contact information. Moreover, the potential participants have the opportunity to either enroll into a waiting list (during inactive recruitment phase) or register for the study (during active recruitment phase). The webpage and ePlatform is fully responsive, transparently adapting to screen size and ensuring a fully functional and rich user experience regardless of whether the platform is accessed using a desktop computer, mobile phone (smartphone), or tablet. |

| Treatment modules | Treatment modules (or chapters) consist of logically ordered webpages with information presented in a variety of formats including text, images, and videos. The users also have access to PDF documents that they can download for off-line use. Worksheets are also embedded within the treatment modules so that users can complete them while reading through the treatment modules. It is worth noting that a few modules (i.e., 2–3) are released each week so that users have specific and different modules to focus on each week. When modules are read, they are marked so that the user and therapist can identify which modules have been covered. Therapists can also use the “treatment module roadmap” function to pre-assign treatment modules to individual users or groups so that the specific modules are automatically released to users on the designated dates. Platform users may also review the usefulness of each module to determine which strategies they find most helpful and will continue to use. Figures 1 and 2 provide examples of a treatment module. |

| Worksheets | Users are provided exercises and homework to ensure that they are fully engaging themselves in the program and are practicing the strategies during daily life. In the current program, quizzes and worksheets are imbedded in the treatment modules. Daily practice can be completed on a worksheet that is linked to the individual modules but saves all the previous answers to enable users to monitor their progress on one worksheet. Figure 3 provides an example of a worksheet. |

| Messaging system | An encrypted messaging system is included to enable two-way communication between therapists and users. The users can communicate with the therapist to seek answers to their questions. Moreover, therapists can use this feature to follow up with the users and to provide individualized feedback on their work. This function works somewhat like an e-mail service. |

| Questionnaires | Users are requested to complete pretreatment and posttreatment outcome measures and some weekly questionnaires. This enables monitoring of outcomes using self-reported outcome measures. A progress bar chart is provided to users as an opportunity to review their weekly scores to monitor whether their tinnitus distress is decreasing during the 8-week period while the intervention is running |

| Functionalities for therapist/administrator | |

| User log | A user log that the therapist or administrator can access serves as a complete journal entry for each participant. The user logs include automatically recorded actions (log in, module assignment, questionnaire completion, etc.). The therapist can also make text journal entries on each user manually. For example, “user is enrolled in the study for treatment group,” “user passed the screening,” or “user did not answer the call.” These notes help the therapist keep track of individual user progress and avoid making notes outside the ePlatform. |

| User list | A user list contains all users registered to the ePlatform with some key information such as user ID, roles assigned (e.g., user vs. therapist), groups assigned (e.g., treatment vs. control group), text notes, number of log-ins, and last log-in. |

| Groups | Groups' functionality helps therapists to assign users to different groups (e.g., treatment group vs. weekly check-in control group, excluded). Users can be added or removed from a group at any stage. Moreover, it is also possible to assign treatment modules, worksheets, or questionnaires to the group so that they are assigned to all individual users at the same time. |

| User hub | The user hub functionality provides all the details about the individual user in a single place. This includes users' demographic details, modules assigned and completed, questionnaire roadmap and completed questionnaires, worksheets completed, messages the participant has sent and received, user logs, and progress bars. Figure 4 provides an example of a progress bar graph regarding weekly tinnitus distress for an individual user. |

| Questionnaire roadmap | The questionnaire roadmap consists of a list of questionnaires and times at which they are assigned to participants. Therapists can activate the roadmap for a user or group, and the ePlatform will automatically send out the questionnaires and reminders according to a roadmap timeline (e.g., every week in the case of a roadmap with weekly measurements). This feature allows full automation of questionnaire administration. Some important functionality features make the data collection and management of these responses user-friendly. First, questionnaires can be automatically assigned to users (e.g., the screening questionnaire immediately after registration) or manually assigned by therapists during or after the treatment. The start date and the specific dates can also be prespecified. Second, the ePlatform allows display of both the individual answers that a user has provided and a graphical representation of changes in predefined variables over time for that specific user. Third, reminder messages are sent automatically by the system to users who have not yet completed the questionnaires, usually the first 3 days following assignment, but this may be adjusted for each study. Finally, data can be conveniently exported into Excel files for direct use in external statistical programs (e.g., SPSS and R). |

Figure 4.

Example of a progress bar graph regarding weekly tinnitus distress. (Tinnitus Handicap Inventory–Screening version was used for weekly monitoring. The scores can range from 0 to 40.)

Phase 3: User Credibility and Acceptability Evaluation

Study Participants

Credibility and acceptance of the materials were evaluated by both health care professionals (n = 11) and patients with bothersome tinnitus (n = 8). Table 3 provides the demographic details of study participants.

Table 3.

Demographic details of study participants.

| Characteristic | Professionals (n = 11) | Patients with bothersome tinnitus (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (M/SD) | 42.9 (14.9) | 30.9 (9.2) |

| Gender (%) | ||

| ▪ Male | 36.4 (n = 4) | 37.5 (n = 3) |

| ▪ Female | 63.6 (n = 7) | 62.5 (n = 5) |

| Language (%) | ||

| ▪ English | 72.7 (n = 8) | 50 (n = 4) |

| ▪ Spanish | 27.3 (n = 3) | 50 (n = 4) |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| ▪ Hispanic or Latino | 36.4 (n = 4) | 87.5 (n = 7) |

| ▪ Non-Hispanic or Latino | 63.6 (n = 7) | 12.5 (n = 1) |

| Race (%) | ||

| ▪ American Indian/Alaska native | — | — |

| ▪ Asian | — | 12.5 (n = 1) |

| ▪ Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | — | — |

| ▪ Black or African American | — | — |

| ▪ White | 72.7 (n = 8) | 62.5 (n = 5) |

| ▪ More than one race | 27.3 (n = 3) | 25 (n = 2) |

| Education (%) | ||

| ▪ Less than high school | — | — |

| ▪ High school | — | — |

| ▪ Some college but not degree | 9.1 (n = 1) | 25 (n = 2) |

| ▪ A university degree | 90.0 (n = 10) | 75 (n = 6) |

| Work (%) | ||

| ▪ Entry level or unskilled work | — | 12.5 (n = 1) |

| ▪ Skilled or professional work | — | 75 (n = 6) |

| ▪ Retired | — | — |

| ▪ Not working | — | 12.5 (n = 1) |

| Profession (%) | ||

| ▪ Audiologists | 63.6 (n = 7) | — |

| ▪ Psychologists | 18.2 (n = 2) | — |

| ▪ Tinnitus researcher | 9.1 (n = 1) | — |

| ▪ Tinnitus support worker | 9.1 (n = 1) | — |

| Users by language | ||

| ▪ English | 8 (72.7) | 4 (50) |

| ▪ Spanish | 3 (27.3) | 4 (50) |

| Tinnitus duration in years (M/SD) | — | 10.2 (8.9) |

| Duration in the profession in years (M/SD) | 14.7 (16.1) | — |

| Ease of computer use (%) | ||

| ▪ Find it hard | — | — |

| ▪ Basic skills | 18.2 (n = 2) | 25 (n = 2) |

| ▪ Frequent user | 80.2 (n = 9) | 75 (n = 6) |

| Internet use (%) | ||

| ▪ Communication such as e-mail or chat | 90.9 (n = 10) | 100 (n = 8) |

| ▪ Reading news | 90.9 (n = 10) | 87.5 (n = 7) |

| ▪ Online shopping | 90.9 (n = 10) | 87.5 (n = 7) |

| ▪ Watching videos | 63.6 (n = 7) | 87.5 (n = 7) |

| ▪ Listening to music | 45.5 (n = 5) | 87.5 (n = 7) |

| ▪ Searching for information | 100 (n = 11) | 87.5 (n = 7) |

Note. Em dashes indicate no data.

Credibility and Acceptance Ratings

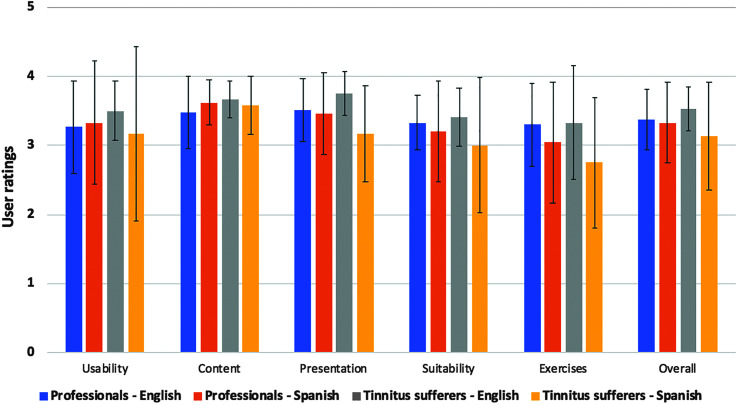

Figure 5 shows the credibility and acceptance ratings of professionals and patients with bothersome tinnitus regarding the ICBT for English- and Spanish-language materials. The average ratings on the full scale and subscales typically were approximately 3.5 on a 5-point scale suggesting a favorable rating toward ICBT. Table 4 provides the median credibility and acceptance ratings for individual items. Appropriate module length element received the lowest median rating (i.e., 2.5–3), whereas the elements straightforward to use, suitable level of information, interesting materials, easy to read, suitable for those with tinnitus, and beneficial topics covered received the highest median rating (i.e., 4). All three items in the exercise section received lower median ratings compared to items in the other sections. Moreover, closer examination of the responses suggested that the professionals who had more substantial experience of working with the tinnitus population evaluated the components of the intervention more favorably with ratings of 4 or 4.5 in a 5-point scale in most elements. We did not record how much time the study participants spent evaluating the ICBT program; doing so could have provided some additional insights.

Figure 5.

Credibility and acceptance rating of health professionals and patients with bothersome tinnitus about the Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for English- and Spanish-language materials. (The response scale included a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Bars represent the mean. Error bars indicate standard deviation.)

Table 4.

Median credibility and acceptability ratings of health professionals and patients with bothersome tinnitus about the Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy.

| Category | Health care professionals | Patients with bothersome tinnitus |

|---|---|---|

| Usability | ||

| Straightforward to use | 4 | 4 |

| Easy to navigate | 3 | 3.5 |

| Appropriate module length | 3 | 2.5 |

| Content | ||

| Suitable level of information | 4 | 4 |

| Informative materials | 3 | 4 |

| Interesting materials | 4 | 4 |

| Presentation | ||

| Content was well structured | 3 | 3 |

| Suitable presentation | 3 | 4 |

| Easy to read | 4 | 4 |

| Suitability | ||

| Suitable for those with tinnitus | 4 | 4 |

| Appropriate range of modules | 3 | 3.5 |

| Beneficial topics covered | 4 | 4 |

| Exercises | ||

| Worksheets were appropriate | 3 | 3.5 |

| Clear instructions on how to practice | 3 | 3.5 |

| Motivation to do the exercises | 3 | 2.5 |

Note. The scores ranged from 1 to 5, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree.

Mann–Whitney U tests suggested no statistically significant difference between ratings by both participant groups for overall scale (U = 42, p = .87) nor the five subscales including Suitability (U = 42, p = .89), Content (U = 39, p = .7), Usability (U = 38, p = .6), Presentation (U = 43, p = .93), and Exercises (U = 37, p = .55).

Perceptions of the Intervention

The optional open-ended questions were examined to identify response patterns. Two overarching themes were identified: aspects of the program that were beneficial or those that were seen as barriers. The program was identified as beneficial as it was informative, had a range of relevant and usable materials, and provided varied presentation of materials as shown in Table 5. The barriers identified included the functional aspects (i.e., issues with ePlatform interface), language, and module length. Sometimes, conflicting ideas were reported. For example, some in the patient group identified that the information could be simplified, whereas professionals suggested that more complex information about neuroanatomy should be added. Additionally, some participants in each group reported that the modules were too long and numerous, whereas other participants suggested additional modules be included. Some of the professionals also wanted a greater emphasis on sound enrichment rather than the focus of the materials being on CBT. When comparing the responses from the English and Spanish participants, coverage was similar except for the barrier of language. For this aspect, the English language coverage was 0.1 and the Spanish coverage was 0.5. A few Spanish participants reported that the language used in the intervention was too complex to understand.

Table 5.

Perceptions of aspects that were beneficial and barriers to undertaking the program.

| Examples from English participants | Examples from Spanish participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficial aspects | ||

| Informative | “It is so informative using science-based information” (Patient with tinnitus) “There is a lot of helpful and appropriate information that is well written and presented using positive affirming language” (Professional) Coverage: 0.4 |

“I learned a lot about tinnitus” (Patient with tinnitus) “The explanations were good to explain how the anguish caused by tinnitus is targeted” (Professional) “It was very useful. I learned new things that kept me wanting to be involved and read more” (Patient with tinnitus) Coverage: 0.5 |

| Range of materials | “Each module addressed a different topic which psychologically could help a patient realize their condition can be helped” (Professional) “I loved how there were SO many different things to focus on. Many topics are covered” (Patient with tinnitus) “There were different sections to reinforce the materials. I liked the goals outlining the beginning of each module and the sections addressing possible challenges” (Professional) “Seeing the doctors discussing different aspects of tinnitus and its management was very helpful” (Patient with tinnitus) Coverage: 0.3 |

“There were so many different strategies that patients can use to improve their tinnitus” (Professional) Coverage: 0.2 |

| Presentation | “The online format is perfect as I can do this in my own time” (Patient with tinnitus) “It is so well written using positive affirming language” (Professional) “The reader is kept engaged by videos that aid understanding of the text” (Patient with tinnitus) “I liked the numerous and varied examples that were provided in each section” (Professional) Coverage: 0.5 |

“I enjoyed the interaction and photos included” (Professional) “The videos were very useful! One of my favorite parts!” (Patient with tinnitus) Coverage: 0.3 |

| Barriers | ||

| Functional aspects | “The size and positioning of the navigation buttons can be improved” (Professional) “There should be a next module button to click at the end of each module to take you to the next module” (Professional) “The subtitles on the videos were sometimes difficult to read and blocked some of the visuals” (Patient with tinnitus) Coverage: 0.5 |

|

| Language | “Use a paragraph format more. I found the flow of reading difficult with the bullet points” (Professional) Coverage: 0.1 |

“It was a little hard to read. There are some words that are difficult to understand” (Patient with tinnitus) “The level of Spanish used is very advanced for the common Spanish speaker. No doubt the translations are accurate, but the vocabulary is too advanced” (Professional) “In some parts Spanish sounds very translated…instead of being more natural” (Professional) Coverage: 0.5 |

| Length | “The first two modules were a bit of an information overload, but really great information” (Patient with tinnitus) Coverage: 0.1 |

“The modules are a bit long, but I understand that all this information is necessary” (Patient with tinnitus) Coverage: 0.1 |

Discussion

In the last decade, reports of various tele-audiological services in the literature range from diagnosis to rehabilitation (for a review, see Beukes et al., 2019; Paglialonga et al., 2018; Tao et al., 2018). The initial efforts in tele-audiology focus predominantly on screening and diagnostic solutions, although there is now a move toward use of eHealth approaches to management and rehabilitation. Internet-based interventions allow individuals with hearing-related conditions to practice condition management by learning and mastering various coping strategies. ICBT for tinnitus demonstrates its effectiveness in the U.K. population (Beukes, Baguley, et al., 2018; Beukes, Andersson, et al., 2018); however, there remains a need to adapt such evidence-based programs to other populations such as that in the United States. This study's focus on the adaptation process, in terms of deciding the features and functionality and ensuring the ePlatform meets U.S. regulatory standards, also provides credibility and acceptability ratings of the adapted platform.

In retrospect, the ePlatform adaptation process was much more time consuming than anticipated. Time delays were due primarily to the software licensing agreement between the institutions required before using the software in a local server. Ensuring the study met the HIPAA requirements was also challenging. Clearly, systems and processes may slow down the adaptation of evidence-based interventions across cultures and/or countries, thereby hampering the initiation, sustainability, and scaling up of such digital interventions. Such important adaptation processes would benefit from clearer delineation of the digital ecosystem across countries that include social, political, economic, legal, and ethical contexts (Labrique et al., 2018).

The cultural and contextual adaptation of evidence-based health interventions is necessary before evaluating the efficacy, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness for different populations (Castro et al., 2010; Lal et al., 2018; Michie et al., 2017). In this study, an expert steering group was consulted and ensured the features and functions of the ICBT program were appropriate for patients with bothersome tinnitus in the United States. Moreover, extensive revisions were made to the intervention to ensure cultural and linguistic adaptation (Beukes et al., 2020). These adaptations were associated with favorable acceptability ratings of ICBT by health professionals and adults with tinnitus. However, acceptability ratings for many items were lower than the ratings of ICBT interventions in the United Kingdom, which were generally more than 4 on a 5-point scale (Beukes et al., 2016). These differences could be attributed at least in part to cultural differences and variances in the health care system. The professional group's ratings were influenced by their perspective that this CBT intervention should include more sound-based materials and more complex neuroanatomical explanations. Conversely, patients wanted certain modules to be simplified. These contrasting views were difficult to reconcile. However, all elements in the exercise section received lower median ratings compared to other sections, which may suggest need for improving these elements. It could also have been hard for participants to relate to these elements and provide appropriate ratings as the intervention was not actively followed as such. The exercises thus did not have as much value as they would to someone working with the intervention on a daily basis. Moreover, Spanish participants made several comments about difficulties understanding the intervention materials due to the level of complexity in modules' language. Considering the user feedback in questionnaire ratings and free-text comments, further adaptations were made to the ePlatform and also the ICBT program in terms of content, length of the chapters, and language complexity in the Spanish version. Efforts were made to make the exercises simpler and more relevant to each module. The appropriateness of these changes, as well as the adequacy of cultural adaptations related to the way tinnitus is perceived across cultures, requires testing during subsequent clinical trials. (Heim & Kohrt, 2019).

A recent study in the United Kingdom suggested that patients have high acceptability of an audiologist-delivered face-to-face CBT program (Aazh et al., 2019). High acceptability was also noted in the ICBT trials in the United Kingdom (Beukes et al., 2016). Hence, continued monitoring to evaluate the acceptance and satisfaction of ICBT will take place during the planned clinical trials in the United States. We anticipate a higher acceptance rating in further evaluations as a result of the implemented changes. Such changes would be important to improve credibility ratings of the intervention before widespread use. Realistic expectations of the intervention should be provided prior to patients undertaking the program. As those with tinnitus represent a heterogeneous population, different users may also prefer certain elements of the program. When evaluating perceptions of a Tinnitus E-Program, Greenwell et al. (2019) identified that users valued the content and skills training more than the self-monitoring tools, online support forum, and therapist support. The themes identified from participant experience undertaking ICBT in the United Kingdom were similar in terms of the benefit of the program being due to its informative nature of the material and the convenient access thereto (Beukes, Manchaiah, Davies, et al., 2018). Conversely, some participants also found the length too long. Overall, the user evaluations of ICBT in the current study were positive and comparable to user evaluations of previous studies from the United Kingdom (Beukes et al., 2016; Greenwell et al., 2019).

Study Limitations

The study has a few limitations. First, the expert steering group only included five health care professionals who were based in the southern part of the United States. A more representative group of professionals from across the United States would have provided more in-depth suggestions and feedback in cultural and linguistic adaptation. Second, the study sample included in user evaluations was predominantly from the same ethnic and educational backgrounds (White and highly educated). Hence, the study results provide a preliminary understanding and are not necessarily generalizable. Further studies should be undertaken with participants from different cultural groups.

Conclusions

Due to the rise of digital therapeutics in health care, we expect that there will be more clinicians and researchers adapting evidence-based health interventions from other cultures and/or countries. We believe that the framework presented in this article could aid those who are interested in such work. Moreover, the features and functionalities of Internet interventions discussed in this article could also be of interest to wider stakeholders including the patient organizations (e.g., American Tinnitus Association) and technology companies involved in the development of digital therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders under Award R21DC017214 (awarded to Vinaya Manchaiah). We would like to thank the American Tinnitus Association for helping in finding the study participants.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders under Award R21DC017214 (awarded to Vinaya Manchaiah).

References

- Aazh H., Bryant C., & Moore B. C. J. (2019). Patients' perspectives about the acceptability and effectiveness of audiologist-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for tinnitus and/or hyperacusis rehabilitation. American Journal of Audiology, 28(4), 973–985. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJA-19-0045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott J. M., Kaldo V., Klein B., Austin D., Hamilton C., Piterman L., Williams B., & Andersson G. (2009). A cluster randomised controlled trial of an Internet-based intervention program for tinnitus distress in an industrial setting. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(3), 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070902763174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G. (2002). Psychological aspects of tinnitus and the application of cognitive–behavioral therapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(7), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00124-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., & Kaldo-Sandström V. (2003). Treating tinnitus via the Internet. CME Journal Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 7, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Strömgren T., Ström L., & Lyttkens L. (2002). Randomized controlled trial of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for distress associated with tinnitus. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(5), 810–816. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200209000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Andersson G., Allen P. M., Manchaiah V., & Baguley D. M. (2018). Effectiveness of guided Internet-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy vs face-to-face clinical care for treatment of tinnitus: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 144(12), 1126–1133. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Baguley D. M., Allen P. M., Manchaiah V., & Andersson G. (2018). Audiologist-guided Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for adults with tinnitus in the United Kingdom: A randomized controlled trial. Ear and Hearing, 39(3), 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Fagelson M., Aronson E. P., Munoz M. F., Andersson G., & Manchaiah V. (2020). Readability following cultural and linguistic adaptations of an Internet-based intervention for tinnitus for use in the United States. American Journal of Audiology, 29(2), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJA-19-00014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Manchaiah V., Allen P. M., Baguley D. M., & Andersson G. (2019). Internet-based interventions for adults with hearing loss, tinnitus, and vestibular disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends in Hearing, 23, 2331216519851749 https://doi.org/10.1177/2331216519851749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Manchaiah V., Andersson G., Allen P. M., Terlizzi P. M., & Baguley D. M. (2018). Situationally influenced tinnitus coping strategies: A mixed methods approach. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(24), 2884–2894. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1362708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Manchaiah V., Davies A. S., Allen P. M., Baguley D. M., & Andersson G. (2018). Participants' experiences of an Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy intervention for tinnitus. International Journal of Audiology, 57(12), 947–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes E. W., Vlaescu G., Manchaiah V., Baguley D. M., Allen P. M., Kaldo V., & Andersson G. (2016). Development and technical functionality of an Internet-based intervention for tinnitus in the UK. Internet Interventions, 6, 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt J. M., Lin H. W., & Bhattacharyya N. (2016). Prevalence, severity, exposures, and treatment patterns of tinnitus in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery, 142(10), 959–965. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2016.1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro F. G., Barrera M. Jr., & Holleran Steiker L. K. (2010). Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 213–239. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cima R. F. F., Andersson G., Schmidt C., & Henry J. A. (2014). Cognitive–behavioral treatments for tinnitus: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology, 25(1), 29–61. https://doi.org/10.3766/jaaa.25.1.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke V., Braun V., & Hayfield N. (2015). Thematic analysis. In Smith J. A. (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (pp. 222–248). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Grady P. A., & Gough L. L. (2014). Self-management: A comprehensive approach to management of chronic conditions. American Journal of Public Health, 104(8), e25–e31. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwell K., Sereda M., Coulson N. S., & Hoare D. J. (2019). Understanding user reactions and interactions with an Internet-based intervention for tinnitus self-management: Mixed-methods evaluation. American Journal of Audiology, 28(3), 697–713. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_AJA-18-0171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heim E., & Kohrt B. A. (2019). Cultural adaptation of scalable psychological interventions: A new conceptual framework. Clinical Psychology in Europe, 1(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.32872/cpe.v1i4.37679 [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. L., & Wilson P. H. (2001). Tinnitus: A self-management guide for the ringing in your ears. Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Hesser H., Weise C., Westin V. Z., & Andersson G. (2011). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive–behavioral therapy for tinnitus distress. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(4), 545–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoare D. J., Kowalkowski V. L., Kang S., & Hall D. A. (2011). Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials examining tinnitus management. The Laryngoscope, 121(7), 1555–1564. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.21825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper K., Weise C., Conrad I., Andersson G., Hiller W., & & Kleinstäuber, M. (2014). Internet-based guided self-help versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(4), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1159/000360705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldo V., Cars S., Rahnert M., Larsen H. C., & Andersson G. (2007). Use of a self-help book with weekly therapist contact to reduce tinnitus distress: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 63(2), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrique A., Vasudevan L., Weiss W., & Wilson K. (2018). Establishing standards to evaluate the impact of integrating digital health into health systems. Global Health: Science and Practice, 6(Suppl. 1), S5–S17. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal S., Gleeson J., Malla A., Rivard L., Joober R., Chandrasena R., & Alvarez-Jimenez M. (2018). Cultural and contextual adaptation of an eHealth intervention for youth receiving services for first-episode psychosis: Adaptation framework and protocol for Horyzons-Canada Phase 1. JMIR Research Protocols, 7(4), e100 https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.8810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manchaiah V., Muñoz M. F., Hatfield E., Fagelson M. A., Aronson E. P., Andersson G., & Beukes E. W. (2020). Translation and adaptation of three English tinnitus patient-reported outcome measures to Spanish. International Journal of Audiology, 59(7), 513–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1717006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz E., & Henry J. A. (2016). Coping with tinnitus. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 53(6), 729–742. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2015.09.0176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna L., Marks E. M., & Vogt F. (2018). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for chronic tinnitus: Evaluation of benefits in a large sample of patients attending a tinnitus clinic. Ear and Hearing, 39(2), 359–366. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., Stralen M. M., & West R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42 https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S., Yardley L., West R., Patrick K., & Greaves F. (2017). Developing and evaluating digital interventions to promote behavior change in health and health care: Recommendations resulting from an international workshop. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(6), e232 https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglialonga A., Cleveland Nielsen A., Ingo E., Barr C., & Laplante-Lévesque A. (2018). eHealth and the hearing aid adult patient journey: A state-of-the-art review. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 17, 101 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12938-018-0531-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinnitus Tackling. (2020). Tackling Tinnitus CBT Program. https://www.tacklingtinnitus.org

- Tao K. F. M., Brennan-Jones C. G., Capobianco-Fava D. M., Jayakody D. M., Friedland P. L., Swanepoel D. W., & Eikelboom R. H. (2018). Teleaudiology services for rehabilitation with hearing aids in adults: A systematic review. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(7), 1831–1849. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-H-16-0397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. M., Hall D. A., Walker D.-M., & Hoare D. J. (2017). Psychological therapy for people with tinnitus: A scoping review of treatment components. Ear and Hearing, 38(2), 149–158. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000000363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. M., Diaz-Artiga A., Weinstein J. R., & Handley M. A. (2018). Designing a behavioral intervention using the COM-B model and the theoretical domains framework to promote gas stove use in rural Guatemala: A formative research study. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 253 http://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5138-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaescu G., Alasjö A., Miloff A., Carlbring P., & Andersson G. (2016). Features and functionality of the Iterapi platform for Internet-based psychological treatment. Internet Interventions, 6, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2016.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise C., Kleinstäuber M., & Andersson G. (2016). Internet delivered cognitive-behavior therapy for tinnitus: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(4), 501–510. http://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]