Abstract

Purpose

Little is known about the professional knowledge, training, and attitudes of current and future speech-language pathologists (SLPs) toward serving people who are transgender. The purpose of this study was to understand the current climate of students and professionals in delivering voice and communications services to people who are transgender. An understanding of these areas is necessary to help practicing and aspiring SLPs work toward cultural competence in serving this population.

Method

A survey was completed by 386 speech-language pathology students and SLPs at three professional conferences. The survey assessed the professional and ethical knowledge, training experiences, and attitudes of the participants in relation to communication services for people who are transgender.

Results

In terms of professional knowledge, the majority of students and experienced SLP respondents agreed or strongly agreed (77.8%) that treating clients who are transgender was within the SLP scope of practice and was their ethical responsibility (82.2%). Regarding training, approximately 20% of survey respondents received training for working with people who are transgender, whereas approximately 8% of survey respondents reported having experience working with clients who are transgender. With respect to attitude, approximately 54% of survey respondents reported being comfortable treating clients who are transgender, and 37% of survey respondents reported they were likely to pursue training for treating clients who are transgender. Additional analyses were completed comparing students and experienced SLPs as well as the influence of geographic region.

Discussion

Students and SLPs were generally knowledgeable of professional guidelines and standards regarding serving people who are transgender. However, in this survey, very few clinicians indicated they had received training to serve this population. Recommendations to address this gap are discussed.

Transgender voice and communication has emerged as an important area in speech-language pathology as more individuals who are transgender have sought out the services of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) to help them express their preferred gender identity. Achieving a gender-congruent voice is critical to the social, psychological, and financial well-being of people who are transgender (Oates & Dacakis, 2015). If individuals who are transgender do not have a voice that matches their gender identity, there could be a significant negative impact on the self-identity, quality of life, and personal safety of people who are transgender whose voices are not congruent with their gender identity (Byrne, 2007; Dacakis et al., 2013; Davies & Johnston, 2015).

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) recognizes the role an SLP has in helping individuals who are transgender with their transition. For example, ASHA's (2016) Scope of Practice cites “transgender communication” (e.g., voice, verbal, and nonverbal communication) as an elective service within the listed speech-language pathology service delivery areas. Furthermore, ASHA constructed a practitioner practical portal to provide information and resources about transgender communication (ASHA, 2019a).

Transgender voice and communication has been a service and research area for SLPs for quite some time, with some case studies in speech-language pathology tracing back to the late 1970s (Oates & Dacakis, 2015). Since then, the majority of the literature has focused on clinical aspects of transgender voice and communication, such as target areas of pitch, resonance, verbal communication, and nonverbal communication (e.g., Adler et al., 2012; Bralley et al., 1978; Gelfer & Tice, 2013; Gelfer & Van Dong, 2013; Mount & Salmon, 1988; Olszewski et al., 2018). However, little is known about SLPs' knowledge of or attitude concerning professional competencies to provide services to people who are transgender. This study aimed to address this gap by assessing the professional and ethical knowledge, training, and attitudes of SLPs to better understand how to train and prepare SLPs to serve clients who are transgender.

Cultural Competence

An important consideration in serving people who are transgender is the role of cultural competence. Cultural competence involves understanding and responding to cultural variables in client/patient/family interactions and is as essential to the successful provision of services as clinical knowledge and skills (ASHA, 2017). Cultural competence is a complex and dynamic process that includes completing self-assessment to consider the influence of one's own biases and beliefs; identifying one's limitations in education, training, and knowledge; and seeking additional resources to develop cultural competence via continuing education and networking (ASHA, 2019b). Developing cultural competence has been described as an ongoing or even life-long learning process. Furthermore, culturally competent clinicians must respond to the unique and individual needs of clients and families based on a variety of factors including, but not limited to, age, disability, gender identity, national origin, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, and veteran status (ASHA, 2017).

An additional factor that has been known to influence one's cultural competence is the environment in which one is raised or lives. Specifically, socioeconomic status and community type can influence how members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) community are perceived and treated. For example, LGBTQ youth in rural communities and communities with lower incomes experience more hostile school climates (Kosciw et al., 2009). Additionally, geographic region has been known to influence the level of tolerance of LGBTQ communities and perceptions of gender norms. Research indicates that the South and Midwest regions appear to be less tolerant of LGBTQ communities than other regions (Powers et al., 2003; Suitor & Carter, 1999; Sullivan, 2004). For example, Kosciw and Diaz's (2006) national study of LGBT youth's school experience suggested that geographic regions such as the South and Midwest would more likely use homophobic language compared to the Northeast and the West. Thus, socioeconomic status, community type, and geographic region have the ability to strongly influence one's beliefs, biases, education, training, and knowledge. These are all factors that can strongly affect their cultural competence.

A relevant theoretical model for cultural competence when working with LGBTQ individuals is defined by the knowledge, skills, and attitude—dimensions of practice (Van Den Bergh & Crisp, 2004). The acquisition of “knowledge” includes the following areas: (a) key terminology and the use of identity-affirming language; (b) demographics and intragroup diversity; (c) an appreciation of the group history and cultural traditions of LGBTQ people; (d) an understanding of group experiences with discrimination, harassment, and oppression; (e) social policies and legislation as it pertains to the community; (f) theoretical, social, and conceptual frameworks related to the community; (g) community resources; and (h) culturally sensitive practice models. The “skills” dimension includes the competencies and behaviors needed to practice as a culturally competent professional, including creating a safe and open environment designing services that are affirming, treating the presenting challenge within the context of the client's life as an LGBTQ person, supporting clients who may be struggling with their membership in the community, and referring clients to appropriate, affirming resources. “Attitude” includes self-assessment and self-reflection of the practitioners' own cultural roots, biases, sensitivity, experiences, and comfortability in working with people who identify as LGBTQ.

SLPs must work toward cultural competence to effectively serve people who are transgender (Hancock, 2015; Masiongale, 2009). Hancock (2015) proposed that increasing knowledge of transgender culture and analyzing one's attitude about the community of people who are transgender is one way to work toward cultural competence. She referenced Turner et al.'s (2006) model of cultural competence to argue that growth is achieved through evolving within four stages: (a) awareness (knowledge), (b) sensitivity (attitudes), (c) competency (skills), and (d) mastery (training others). This model included important topic areas necessary for achieving LGBTQ cultural competency as one progresses through the four stages. Knowledge, training, skills, and attitudes are core elements of this model as practitioners build upon their attainment of knowledge about serving the community of LGBTQ people, analyze their own attitudes and biases, and demonstrate and apply skills in simulated and actual settings.

Knowledge, Training, and Attitudes

There is a necessity to promote and provide quality care to individuals who are transgender by highly trained professionals (World Professional Association for Transgender Health, 2011). Given the limited information regarding the knowledge, training, skills, and attitudes of SLPs who serve people who are transgender, it was necessary to investigate the literature of other health care providers' experiences. This too was limited and required a broader search to include individuals who are LGBTQ. Most studies of health care providers such as medical students, nurse practitioners, physicians, primary care providers, and SLPs found that there was a lack of knowledge in how to properly serve this population and limited clinical experiences (Kelly et al., 2008; Kline, 2015; Poteat et al., 2013; Snellgrove et al., 2012).

Kelly et al. (2008) argued that the health of persons who are LGBTQ had been a severely understudied and underserved population in American medical education. The authors designed and implemented curriculum within a medical school course to educate second-year medical students about the health of people who are LGBTQ and assessed students' knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the health of people who are LGBTQ before and after the intervention. Students demonstrated significant change in knowledge and attitudes, including increased knowledge of differential access to health care and attitudes, increased willingness to treat people with gender identity issues, and enhanced awareness that sexual orientation and identity are relevant to clinical practice. Thus, the training that medical students received significantly changed the knowledge and attitudes on four out of 16 survey questions. This study demonstrated that explicit instruction within the curriculum has the potential to change knowledge and attitudes as it relates to the community of LGBTQ individuals.

Similarly, Kline (2015) examined the attitudes of eight nurse practitioners who lived across four states toward gender variance and perceived need and interest in learning standards of care for individuals who are transgender. This study included two intervention groups of nurse practitioners who viewed a short video of people who are transgender describing their health care needs and two control groups who did not. A 16-item survey was administered to all nurse practitioners related to their knowledge, attitudes, and skills in providing health care to people who are transgender. Findings of the effectiveness of the video were inconclusive due to the small response rate. The descriptive data indicated that the majority of nurse practitioners had little to no understanding of the health needs, standards of care, or available resources for serving patients who are transgender. The author suggested that this lack of knowledge had far-reaching consequences for patient care. However, the majority of the nurse practitioners who completed the survey indicated that they both wanted and needed continuing education and other resources to better serve people who are transgender.

A lack of knowledge and an inability to identify and access resources to serve patients who are transgender was also echoed in Snelgrove et al.'s (2012) qualitative interview study of 13 physicians. Additional barriers to providing patient care included complex ethical decision making in counseling patients in transition-related care and diagnosing versus pathologizing trans status and health system deterrents based on cisgender “two-gender medicine” norms. Findings from this study indicated the need for increased knowledge and awareness of clinical guidelines for providing trans-related care in medical education and at the institutional level. Furthermore, it suggested a need for an innovative trans-friendly and trans-focused primary care model.

A lack of trans-friendly health care experiences was the primary theme in Poteat et al.'s (2013) qualitative study of 12 primary care providers and 55 individuals who were transgender. Findings indicated that the providers were uncertain of how to treat patients who were transgender and that patients who were transgender generally did not believe that their provider would be able to meet their needs. The authors suggested that structural and institutional stigma led to the experiences of individuals who are transgender being virtually absent from most medical education, and thus, most providers were ill-equipped to provide competent care. The participants who were transgender described experiences of extreme stigma and discrimination both within their medical interactions and in other environments—to the point where many generally anticipated or even accepted that ignorant or discriminating behaviors would occur. The authors argued that stigma and discrimination in health care interactions served to reinforce the power dynamic in medical encounters while revealing providers' ambivalence toward people who are transgender and their care.

There have been no identified studies evaluating the knowledge and attitudes of SLPs toward serving the community of people who are transgender. This is important because the ASHA's (2016) Scope of Practice explicitly defines transgender communication service as within the scope for SLPs. The closest study that assesses knowledge, training, skills, and attitudes of SLPs was completed by Hancock and Haskin (2015), who assessed the knowledge and attitudes of SLPs toward the population of individuals who are LGBTQ. Two hundred seventy-nine SLPs completed an online survey regarding knowledge, comfort, and feelings about working with people who are LGBTQ as well as questions regarding terminology and culture. Findings indicated that SLPs exhibited more comfort than knowledge in relation to the community of LGBTQ people. Additionally, SLPs harbored slightly more negative feelings toward transgender people compared to other members of the community of people who are LGBTQ.

Purpose and Research Questions

To date, there have been no studies that examined the professional knowledge, training, and attitudes of current and future SLPs toward serving the transgender population. Knowing this information will provide a barometer of students' and professionals' knowledge, training, and attitudes and can inform graduate training practices and professional development. The ASHA (2014) standards and procedures for the certificate of clinical competence in speech-language pathology are a guideline for the requirements, knowledge outcomes, skills outcomes, and ongoing experiential and educational procedures for SLPs. Specifically, Standard IV encompasses knowledge requirements including content knowledge, clinical knowledge, research knowledge, ethical knowledge, and professional knowledge.

This study focused broadly on knowledge, training, and attitudes of students and SLPs regarding the services of clients who are transgender. Professional and ethical knowledge in this study refers to demonstrated knowledge in contemporary professional issues and trends in professional practice. Rather than focus on specific skills, we decided to explore training experiences as training is the foundation for skills, and it is not known how many students and SLPs are being trained in this growing area of practice. Attitude questions targeted areas concerning professional comfortability and practice in regard to serving people who are transgender. The purpose of this study was to understand the current climate of students and SLPs in delivering voice and communication services to people who are transgender. The following research questions were asked:

What are the knowledge (professional and ethical), training experiences, and attitudes of students and SLPs collectively regarding voice and communication services for individuals who are transgender?

Do professional years of experience or geographic region influence knowledge, training experiences, and attitudes regarding voice and communication services for individuals who are transgender?

Do students and SLPs' knowledge of professional ethical considerations align with their attitude of providing services?

Hypotheses

It was hypothesized that professionals with more years of experience would demonstrate more knowledge and training in services for people who are transgender but may have attitudes toward the concept of transgender services that are less tolerant. This hypothesis was supported by Hancock and Haskin's (2015) study, which found students reported lower knowledge and attitude (comfort) than experienced SLPs regarding their role with clients who are LGBTQ but were more knowledgeable of LGBTQ terminology. It was also hypothesized that participants in the Northeast and West would have more knowledge and training and be more tolerant toward working with people who are transgender than respondents in the Midwest and the South as several studies have indicated geographical differences in tolerance toward communities of people who are LGBTQ (Powers et al., 2003; Suitor & Carter, 1999; Sullivan, 2004). Lastly, it was hypothesized that students' and SLPs' professional knowledge would align strongly with their attitude of providing services to people who are transgender. This hypothesis was supported by Kelley et al. (2008), who found that improving medical students' knowledge changed their attitude toward providing services to clients who were LGBTQ.

Method

Procedure

An institutional review board approved a 12-item survey, which was administered at three Communication Science and Disorders professional conferences: the Georgia Speech-Language-Hearing Association, the National Black Association for Speech-Language and Hearing, and ASHA in February 2017, April 2017, and November 2017, respectively. The first author or graduate student research assistants approached potential participants who were stationary in the conference hallways between sessions. If they appeared to be in an intense conversation or activity, they were not approached, but if they appeared open to being engaged, they were asked to complete the survey. If the addressed person was a speech-language pathology student or practicing SLP, they were asked to complete the survey on an electronic tablet (i.e., iPad). Of the 390 approached participants, 379 fully completed the survey and 10 partially completed the survey. One person was removed from the analysis as no descriptives of this individual were recorded. Data were collected in Qualtrics data software and saved in a password-protected cloud-based server. Demographic characteristics for participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of participants.

| Question | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| I identify as | ||

| Female | 361 | 93.52 |

| Male | 23 | 5.96 |

| Transgender | 2 | 0.52 |

| What is your age range? | ||

| 18–29 years old | 194 | 50.00 |

| 30–49 years old | 127 | 32.73 |

| 50–64 years old | 48 | 12.37 |

| 65 years and older | 19 | 4.90 |

| Resident of | ||

| Region 1: Northeast | 37 | 19.37 |

| Region 2: Midwest | 33 | 17.28 |

| Region 3: South | 34 | 17.80 |

| Region 4: West | 76 | 39.79 |

| Outside U.S. | 11 | 5.76 |

| Conference | ||

| ASHA | 153 | 39.33 |

| GSHA | 108 | 27.76 |

| NBASLH | 128 | 32.90 |

| What is your professional level? | ||

| Undergrad | 46 | 11.86 |

| Grad | 131 | 33.76 |

| Fellow | 11 | 2.84 |

| Licensed | 200 | 51.55 |

| How many years of experience do you have as a speech-language pathologist? | ||

| None | 167 | 41.96 |

| 0–5 years | 68 | 17.09 |

| 6–10 years | 42 | 10.55 |

| 11–15 years | 33 | 8.29 |

| > 15 years | 88 | 22.11 |

| Have you had experience treating transgender patients for voice and communication? | ||

| No | 355 | 91.49 |

| Yes | 33 | 8.51 |

Note. The count refers to the number of survey respondents, and the percentage is the corresponding percent out of participants who answered the question. ASHA = American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; GSHA = Georgia Speech-Language-Hearing Association; NBASLH = National Black Association for Speech-Language and Hearing.

Survey

The goal of the survey was to evaluate the professional and ethical knowledge, training, and attitudes of students and SLPs in relation to voice and communication services for people who are transgender. The survey was grounded within the theoretical model related to the knowledge, skills, and attitude dimensions of practice (Van Den Berg & Crisp, 2004). The questions were developed in part based on Kline's (2015) survey of the health care knowledge, skills, and attitudes of nurse practitioners in the health care provision of individuals who are transgender. Similarly, our survey addressed questions regarding professional and ethical knowledge, training, and attitudes about serving people who are transgender using a Likert scale. Additionally, our study included questions on ethical responsibility and scope of practice issues as the idea for the study was formed out of a student presentation on an ethical scenario in a professional practices course. The survey was designed to be an initial study that was limited to 5 min to increase the response rate and to gather some initial perceptions on knowledge, training, and attitudes. It would serve as a foundation for further studies that would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the perceptions of serving clients who are transgender. This study's survey featured five demographic questions and seven Likert-style questions, including two knowledge-based questions, two training-based questions, and three attitude-based questions. The demographic questions included topics of gender, age, location, professional status, and years of experience. Survey respondents were asked to rate their knowledge, training, and attitudes toward serving individuals who are transgender, which were considered indirect measures of awareness, competency, and sensitivity (Turner et al., 2006). The entire survey is presented in the Appendix.

Data Analysis

Medians, percentage response rates, and nonparametric statistics were used to understand the differences between response rates within each group (i.e., years of experience). The sample distribution of Questions 7, 8, 11, and 12 were negatively skewed, Question 9 was positively skewed, and Question 10 was close to normal. Due to the nature of the data distribution and unequal sample sizes within demographic groups, nonparametric statistics were used for all comparisons between groups: years of experience, status, and geographic regions. Three of the demographic questions (i.e., age range, professional level, and experience) were similar, and thus, we conducted a correlation analysis based on Spearman rho to identify if they were redundant or described different groups of the population. Findings indicated that they were strongly correlated (r = .84). Therefore, years of experience and region were used in this study to conduct inferential statistics. The responses of each question were analyzed within corresponding groups (e.g., year of experience, region) via Kruskal–Wallis rank-sum test. If the test statistics showed a difference of at least 95% confidence within a group, pairwise Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were employed to identify which subcategory within the group showed statistically significant differences at a false discovery rate adjusted p value of .05. During data analysis, positive responses included “agree” and “strongly agree,” whereas negatives responses included “disagree” and “strongly disagree.”

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Respondent Characteristics

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Three hundred ninety people initiated the survey of which 386 answered all survey questions. Survey respondents were represented roughly the same across the three conferences: the Georgia Speech-Language-Hearing Association (27.8%), the National Black Association for Speech-Language and Hearing (32.9%), and ASHA (39.3%). Thirty-six states, the District of Columbia, and people from outside the United States were represented in the survey. Eleven respondents reported not residing in the United States. The majority of the survey respondents came from the southern region (59.3%). The three states most represented were Georgia (32.4%), California (13.2%), and Florida (5.4%).

Knowledge, Training, and Attitudes

Results of survey responses to questions regarding knowledge, training, and attitudes are displayed in Table 2. In terms of knowledge, the majority of respondents agreed or strongly agreed (77.8%) that treating voice clients who are transgender was within the SPL scope of practice and was their ethical responsibility (82.2%).

Table 2.

Summary of survey respondents.

| Category and question | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Undecided | Agree | Strongly agree | Total answers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | ||||||

| Question 7: Treating transgender voice clients is within my scope of practice as an SLP or will be within my scope of practice when I am an SLP. | 22 | 14 | 50 | 140 | 161 | 387 |

| 5.7% | 3.6% | 12.9% | 36.2% | 41.6% | ||

| Question 11: Treating transgender clients who are referred to me is my ethical responsibility. | 17 | 10 | 42 | 122 | 197 | 388 |

| 4.4% | 2.6% | 10.8% | 31.4% | 50.8% | ||

| Training | ||||||

| Question 9: I have received training for working with the transgender population. | 165 | 119 | 31 | 55 | 19 | 389 |

| 42.4% | 30.6% | 8.0% | 14.1% | 4.9% | ||

| Question 10: I am likely to pursue training for treating transgender voice patients | 44 | 80 | 119 | 87 | 57 | 387 |

| 11.4% | 20.7% | 30.7% | 22.5% | 14.7% | ||

| Attitude | ||||||

| Question 8: I am comfortable with treating transgender voice patients. | 49 | 59 | 71 | 108 | 101 | 388 |

| 12.6% | 15.2% | 18.3% | 27.8% | 26.0% | ||

| Question 12: Transgender voice therapy is a medical and/or educational necessity for LGBTQ individuals. | 20 | 20 | 91 | 102 | 153 | 386 |

| 5.2% | 5.2% | 23.6% | 26.4% | 39.6% | ||

Note. Numbers in cells represent counts and corresponding percentages of survey respondents. SLP = speech-language pathologist; LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer.

Regarding training, approximately 20% of survey respondents received training for working with people who are transgender, whereas approximately 8% of survey respondents reported having experience working with clients who are transgender. Thirty-seven percent of survey respondents reported they were likely to pursue training for treating clients who are transgender.

With respect to attitude, approximately 54% of survey respondents reported being comfortable treating clients who are transgender. Approximately 66% of survey respondents felt therapy for clients who are transgender is a medical or educational necessity.

Years of Experience and Geographic Region Influences

Knowledge. Results of response distributions for Questions 7 and 11 as a function of survey respondents' years of experience are displayed in Table 3. Knowledge was assessed by Questions 7 and 11. On Question 7, SLPs with no experience differed from those with more than 15 years of experience on whether treating patients who are transgender is within their scope of practice (W = 8,452.5, p = .0009). Almost 50% of SLPs with no experience strongly agreed that is within their scope of practice to serve patients who are transgender, whereas only 33% of very experienced SLPs strongly agreed. Furthermore, 11.4% of very experienced SLPs believed that it is not within their scope at all to treat people who are transgender compared to 0% in the group of SLPs in training.

Table 3.

Response distributions (percentages) for Questions 7 and 11 as a function of survey respondent “years of experience.”

| Years of experience | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Undecided | Agree | Strongly agree | Not answered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 7 | ||||||

| Nonea | 0 | 1.27 | 12.1 | 37.6 | 47.8 | 1.27 |

| 0–5 | 4.41 | 5.88 | 13.2 | 33.8 | 42.6 | 0 |

| 6–10 | 9.52 | 9.52 | 14.3 | 31 | 35.7 | 0 |

| 11–15 | 15.2 | 0 | 6.06 | 39.4 | 39.4 | 0 |

| > 15a | 11.4 | 3.41 | 15.9 | 36.4 | 33 | 0 |

| Question 11 | ||||||

| Noneb, c, d | 1.27 | 0.64 | 9.55 | 28.7 | 59.9 | 0 |

| 0–5e | 1.47 | 4.41 | 7.35 | 36.8 | 50 | 0 |

| 6–10d | 7.14 | 4.76 | 11.9 | 35.7 | 40.5 | 0 |

| 11–15b, e | 12.1 | 3.03 | 12.1 | 42.4 | 27.3 | 3.03 |

| > 15c | 7.95 | 3.41 | 14.8 | 26.1 | 47.7 | 0 |

Note. Question 7: Treating transgender voice clients is within my scope of practice as a speech-language pathologist or will be within my scope of practice when I am a speech-language. Question 11: Treating transgender clients who are referred to me is my ethical responsibility. Numbers in cells equal the percentage of survey respondents within each Likert scale. Subscripted lower letters (a, b, c, d, e) indicate pairwise statistical significance between the specified groups within each question. There were no statistical differences between regions for Questions 7 and 11.

The responses to whether it is or is not an ethical responsibility to treat referred clients who are transgender (Question 11, knowledge) are highly dependent on the years of experiences. SLPs with no experience statistically significantly differed from those with 6–10 years (W = 4,056, p = .010), 11–15 years (W = 3,418.5, p = .0003), and > 15 years of experience (W = 8,113.5, p = .012). SLPs with no experience strongly agreed that it is their ethical responsibility to serve patients who are transgender. Additionally, SLPs with 0–5 years of experience statistically significantly differed from SLPs with 11–15 years of experience (W = 1,385.5, p = .018). SLPs with 0–5 years of experience agreed that it is their ethical responsibility to serve patients who are transgender. Based on these data, more than 85% of SLPs with less than 5 years of experience believed it was their ethical responsibility to serve patients who are transgender compared to a lower percentage in more experienced SLPs (from 68.7% to 76.2%).

Overall, SLPs with less experience were more knowledgeable of their scope and ethical responsibility. Responses based on geographical regions did not show any statistically significant differences.

Training. Results of response distributions for Question 9 as a function of survey respondents' years of experience and region are displayed in Table 4. Training was assessed by Question 9, which asked participants if they had received training for working with clients who are transgender. SLPs with no experience statistically significantly differed from those with 6–10 years of experience (W = 4,288.5, p = .002). Approximately 20% of those with no experience reported receiving training, whereas only 7% of SLPs with 6–10 years of experience reported receiving training. Overall, the majority of all participants had not received training.

Table 4.

Response distributions (percentages) for Question 9 as a function of “years of experience” and “region.”

| Question 9 | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Undecided | Agree | Strongly agree | Not answered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of experience | ||||||

| Nonef | 35 | 36.9 | 7.64 | 15.9 | 4.46 | 0 |

| 0–5 | 41.2 | 30.9 | 11.8 | 11.8 | 4.41 | 0 |

| 6–10f | 61.9 | 26.2 | 4.76 | 4.76 | 2.38 | 0 |

| 11–15 | 48.5 | 27.3 | 12.1 | 9.09 | 3.03 | 0 |

| > 15 | 45.5 | 21.6 | 5.68 | 19.3 | 7.95 | 0 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1.27 | 0.64 | 9.55 | 28.7 | 59.9 | 0 |

| Midwest | 1.47 | 4.41 | 7.35 | 36.8 | 50 | 0 |

| Southg | 7.14 | 4.76 | 11.9 | 35.7 | 40.5 | 0 |

| Westg | 12.1 | 3.03 | 12.1 | 42.4 | 27.3 | 3.03 |

| Outside U.S. | 7.95 | 3.41 | 14.8 | 26.1 | 47.7 | 0 |

Note. Question 9: I have received training for working with the transgender population. Numbers in cells equal the percentage of survey respondents within each Likert scale. Subscripted lower letters (f, g) indicate pairwise statistical significance between the specified groups within each question.

Additionally, SLPs from the West statistically significantly differed from SLPs in the South (W = 6,808.5, p = .003) regarding their training to serve individuals who are transgender. More SLPs in the West (30%) reported that they had received training compared to the South (15%).

Years of experience did not play a role in SLPs' likeliness to pursue training for treating individuals who are transgender (Question 10). There were no statistically significantly differences between SLP subgroups. Across all groups, approximately one third were likely to pursue training, approximately one third were unsure, and one third were unlikely to pursue training.

Attitude. Results of response distributions for Question 8 as a function of survey respondents' years of experience are displayed in Table 5. Additionally, response distributions for Question 12 as a function of experience and region are displayed in Table 6.

Table 5.

Response distributions (percentage) for Question 8 as a function of survey respondent “years of experience.”

| Years of experience | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Undecided | Agree | Strongly agree | Not answered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noneh, i | 8.28 | 14 | 16.6 | 28 | 32.5 | 0.637 |

| 0–5j | 2.94 | 17.6 | 25 | 27.9 | 26.5 | 0 |

| 6–10h, j | 33.3 | 14.3 | 9.52 | 23.8 | 19 | 0 |

| 11–15i | 24.2 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 24.2 | 15.2 | 0 |

| > 15 | 13.6 | 14.8 | 20.5 | 29.5 | 21.6 | 0 |

Note. Question 8: I am comfortable with treating transgender voice patients. Numbers in cells equal the percentage of survey respondents within each Likert scale. Subscripted lower letters (h, i, j) indicate pairwise statistical significance between the specified groups within each question. There were no statistical differences between regions for Question 8.

Table 6.

Response distributions (percentage) for Question 12 as a function of survey respondent “years of experience” and “region.”

| Question 12 | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Undecided | Agree | Strongly agree | Not answered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of experience | ||||||

| Nonek | 2.55 | 4.46 | 22.3 | 28 | 42 | 0.637 |

| 0–5l | 1.47 | 7.35 | 17.6 | 23.5 | 50 | 0 |

| 6–10 | 9.52 | 9.52 | 33.3 | 11.9 | 35.7 | 0 |

| 11–15k, l | 12.1 | 0 | 33.3 | 36.4 | 15.2 | 3.03 |

| > 15 | 7.95 | 4.55 | 20.5 | 28.4 | 37.5 | 1.14 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 0 | 8.11 | 21.6 | 24.3 | 45.9 | 0 |

| Midwest | 3.03 | 9.09 | 18.2 | 27.3 | 42.4 | 0 |

| Southm | 6.11 | 5.68 | 25.8 | 27.9 | 33.6 | 0 |

| Westm | 3.95 | 1.32 | 17.1 | 25 | 51.3 | 1.33 |

| Outside U.S. | 9.09 | 0 | 36.4 | 9.09 | 45.5 | 0 |

Note. Question 12: Transgender voice therapy is a medical and/or educational necessity for LGBTQ. Numbers in cells equal the percentage of survey respondents within each Likert scale. Subscripted lower letters (k, l, m) indicate pairwise statistical significance between the specified groups within each question. LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer.

Level of comfort in treating voice patients who are transgender depended on SLPs' years of experience assessed by Question 8. SLPs with no experience statistically significantly differed from SLPs with 6–10 years of experience (W = 4,251, p = .002) and 11–15 years of experience (W = 3,347.5, p = .005). SLPs with no experience demonstrated the highest level of comfort. SLPs with minimal experience (0–5 years) also statistically significantly differed to their slightly more advanced colleagues who had 6–10 years of experience (W = 1,827, p = .012). Essentially, respondents with less years of experience expressed more comfort in serving clients who are transgender than those with more years of experience.

Level of comfort in services being medically and/or educationally necessary for patients who are transgender depended on SLPs' years of experience as assessed by Question 12. SLPs with no years of experience statistically significantly differed from SLPs with 11–15 years of experience (W = 3,239.5, p = .005). SLPs with no years of experience believed these services are medically or educationally necessary. Additionally, SLPs with 0–5 years of experience statistically significantly differed from those with 11–15 years of experience (W = 1,475, p = .003). There were fewer SLPs with 11–15 years of experience believing that these services are a medical or educational necessity compared to any other years of experience.

A difference in attitude toward transgender voice therapy being a medical and/or educational necessity was also detected across regions. The West and the South demonstrated a statistically significant difference in response rates to this question (W = 6,655.5, p = .030). Approximately 75% of SLPs from the West believed serving clients who are transgender is a medical and/or ethical necessity compared to 61% in the South.

Relationship Between Knowledge and Attitude

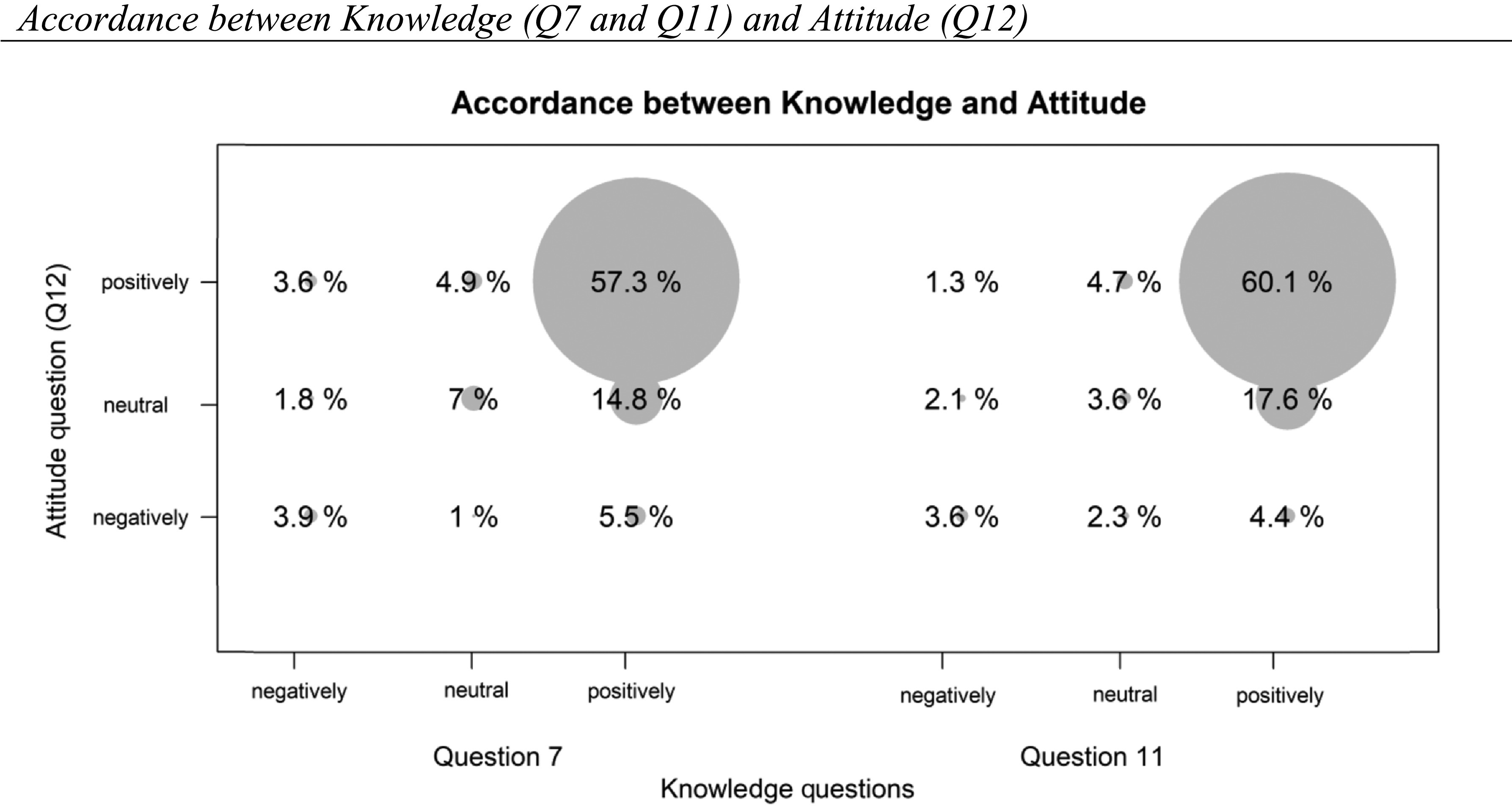

Accordance between respondents' knowledge responses on Questions 7 and 11 and to their attitude on Question 12 were evaluated and presented in Figure 1. Approximately 60% of respondents answered positively to both the knowledge questions (Questions 7 and 11) and the attitude question (Question 12). All paired positive, neutral, and negative responses were evaluated, and about 68% were in alignment. Of these survey respondents, approximately 4% did not acknowledge that services to people who are transgender were within the scope of practice nor a medical or educational necessity and 7% were impartial to both (see comparison between Questions 7 and 12 in Figure 1). In terms of ethical responsibilities, the response percentage was slightly lower: 3.6% did not acknowledge that services to people who are transgender were an ethical responsibility nor a medical or educational necessity, and the same percentage was impartial to both (see comparison between Questions 11 and 12 in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bubble chart shows paired response percentages between knowledge questions and attitude question. Gray areas indicate the percentage of survey participants with corresponding responses between the two questions. Between Questions 7 and 12, there are 384 matched responses, and between Questions 11 and 12, there are 386 matched responses.

Discussion

In light of ASHA's (2016) Scope of Practice and the need for clinically and culturally competent providers, this study assessed the current knowledge, training, and attitudes of students and SLPs in serving clients who are transgender. An understanding of current professional knowledge, training experiences, and attitudes are necessary in order to adequately train and prepare preprofessionals and professionals to serve this population. Student and current SLPs were surveyed at professional conferences regarding their knowledge, training, and attitudes of working with people who are transgender. These dimensions of practice are critical to the development of cultural competence given the uniqueness of this population.

Overall Knowledge, Training, and Attitudes of Students and SLPs

Knowledge

In general, students and SLPs were knowledgeable of professional guidelines, standards, and conduct surrounding services for people who are transgender. One reason respondents may have been knowledgeable about professional guidelines for people who are transgender could be due to the cultural shift within ASHA to increase awareness of transgender services. For example, ASHA identified these services in their 2016 scope of practice document (ASHA, 2016) and included services for people who are transgender in their practice portal for practicing SLPs (ASHA, 2019a). Furthermore, practicing SLPs have published textbooks regarding this topic in which practitioners could access to improve their knowledge (Adler et al., 2012; Olszewski et al., 2018).

Training

Overall, a small percentage of respondents (19%) indicated that they had received training for working with people who were transgender and seeking communication services. These findings are echoed in medical education (Kelly et al., 2008; Poteat et al., 2013; Snellgrove et al., 2012), nursing education (Kline, 2015), and speech-language pathology (Hancock & Haskin, 2015). Findings indicate that there is likely a shortage of providers with the training, skills, and experience to serve this population. One possible reason why there is a shortage of trained SLPs could be because working with people who are transgender is a specialized area and not all SLPs are interested in this area. Another reason could be that, because this area is specialized, it is difficult for professors to implement this content in graduate school if they are not knowledgeable, comfortable, or experienced in working with this population. Some have argued that the depth of research in evidence-based approaches to providing communication services to people who are transgender is relatively sparse in some specific areas (Azul et al., 2017; Olszewski et al., 2018). This lack of depth may make it more difficult to train clinicians in clinical methods that are solidly grounded in evidence-based approaches. Finally, professors may be apprehensive to integrate this content area when training students who may not be open to serving this population, especially in programs located in more conservative areas or regions.

Attitude

Almost half of the respondents felt uncomfortable or indifferent treating clients who were transgender, and over one third were not likely to pursue training in this area. Respondents may have not been as comfortable treating clients who are transgender for a variety of reasons. For example, this may not have been their area of practice, they may not have felt that they had the necessary knowledge or skills to serve this population, or they may not feel comfortable interacting with people who are transgender.

Influence of Experience and Region on Knowledge, Training, and Attitudes

Years of Experience on Knowledge and Training

Although it was hypothesized in Research Question 2 that SLPs with more experience would demonstrate more knowledge and training than those with less experience, our hypothesis was not confirmed. The findings indicated that students were more knowledgeable about scope of practice and ethical responsibility of serving individuals who are transgender and had received more training than professional SLPs. Our hypothesis that more experienced SLPs would have less tolerant attitudes toward providing services to people who are transgender was confirmed. This study found evidence that SLPs with less experience felt more comfortable serving this population, were more likely to pursue training, and perceived the treatment of the population to be of educational and medical necessity.

These findings extend the current literature by examining the knowledge, training, and attitude of SLPs about specifically serving people who are transgender. Hancock and Haskin's (2015) study found that SLPs who were older were more knowledgeable about the role of SLPs in care and providing services. However, the current study found less experienced SLPs were more knowledgeable than more experienced SLPs as it relates to the SLPs' role in serving people who are transgender. Hancock and Haskin (2015) results did not indicate strong evidence for age affecting attitude. They found that, in only one out of five comfort areas, age did affect the attitudes of SLPs and students as it related to the community of people who are LGBTQ. Findings regarding training were not reported (Hancock & Haskin, 2015). The contrast in findings between the two studies could be attributed to differences in the survey questions, the number of survey questions, the methods of data collection, and the sampling of the participants.

It is reasonable to expect students and more recent graduates to be more knowledgeable and open to working with people who are transgender because of their current or more recent role as professional full-time learners. Students and recent graduates are in some ways more connected to the most recent literature and current trends in the field. For example, the landscape of practice has expanded in recent years with the modernization of clinical practice in regard to addressing current issues such as telepractice, literacy, accent modification, and communication services for clients who are transgender (ASHA, 2016). It is possible that, as seasoned professionals find their niches in clinical practice, they are more selective in the work they choose and may not engage with new areas of practice.

Years of Experience on Attitude

Years of experience could also affect attitudes toward persons who are transgender, as it did in our study where students and recent graduates were more open to serving clients who were transgender than more seasoned professionals. Biological age was strongly correlated with years of experience in this study, and therefore, years of experience was the measure used. We could not locate literature on how age affects health care workers' attitudes or perceptions for serving people who are transgender. However, the literature on the effect of biological age on attitudes toward people who are transgender is both limited and mixed. Landén and Innala's (2000) study in Sweden indicated older people held more restrictive attitudes about people who are transgender. Similarly, King et al. (2009) argued that age was generally a key factor in attitudes toward people who are transgender. Their study in Hong Kong indicated that age, educational level, and degree of contact with people who are transgender affected perspectives toward people who are transgender with younger people holding more positive attitudes than older people. However, Norton and Herek's (2013) large-scale study in the United States did not implicate age as a significant factor in attitude but did indicate gender; region; social, psychological, and political views; religiosity; and contact with sexual minorities as important factors.

It is possible that SLPs with more experience in the current study may have not been as comfortable treating clients who are transgender for a variety of reasons. This may not have been their area of practice, they may not have felt that they had the necessary knowledge or training to serve this population, or they may not feel comfortable interacting with people who are transgender. Seasoned SLPs may be more resistant to the updated professional roles than less experienced SLPs because they are likely to have their own opinions that counter the updated breadth of clinical practice provided by the national governing organization. As a result, many clinicians may have to weigh their own personal beliefs against what their professional association says is appropriate. For example, some ASHA professionals may have moral or religious beliefs against changing one's gender identity, which could cause conflict with their professional ethics. Moreover, clients who are transgender may not present with a communication disorder in the traditional sense if there is no vocal pathology or abnormality. Therefore, the issue of delivery of services to clients who are transgender could constitute a conflict of interest in which it could be difficult to maintain the separation of personal interests from professional services.

Region

Our hypothesis in Research Question 2 that people in the Northeast and West would have more knowledge and training and be more open to work with people who are transgender than respondents in the Midwest and the South was partially confirmed. Our findings indicated that survey respondents in the West demonstrated significantly more training and positive attitudes toward working with people who are transgender than survey respondents in the South. These findings are new in the literature as no other study has examined knowledge, training, and attitudes within the regions of the United States regarding the treatment of voice and communication for people who are transgender. The closest finding was that of Hancock and Haskin (2015), who found SLPs in the United States and Canada were more knowledgeable than SLPs in Australia and New Zealand about the community of people who are LGBTQ.

One reason we found differences between the West and the South could have been due to the large number of survey respondents in these two regions. Traditionally, the South region has been more socially conservative than the West (Movement Advancement Maps, 2019; Transgender Law Center, 2019). Thus, people in the West would have more experience and be more open to and comfortable with working with this population. Additionally, a majority of respondents in the West were from California, where there is more acceptance of people in the community who are LGBTQ (Refinery 29, 2019). Most of the survey respondents in the South were from Georgia. Based on the clinic websites of graduate speech-language pathology programs in these states, two out of 19 schools in California offered clinical transgender services, whereas one out five schools in Georgia offered these clinical services. Additionally, the percentage of individuals who are transgender in California and Georgia were similarly ranked at 2% and 4%, respectively (Flores et al., 2016). This would lead us to think that the predominant reason for regional difference in training and attitude toward serving transgender clients between the West and the South is cultural and not based on graduate program training or number of individuals who are transgender residing in those states.

Alignment of Responses on Knowledge and Attitudes

It was hypothesized in Research Question 3 that students and SLPs' knowledge of scope of practice and ethical responsibilities would align with their attitude of providing services to people who are transgender. Responses to knowledge questions regarding scope of practice and ethical responsibility yielded similar results. Specifically, approximately 68% of survey responses to knowledge and attitude questions aligned. However, a small percentage (9.1% for Question 7 and 5.7% for Question 11) replied very differently to the knowledge questions compared to the attitude question.

Out of all the respondents that aligned their knowledge and attitude responses, 57% (Question 7) and 60% (Question 11) of the survey respondents replied positively in accordance to knowledge and attitude questions. This means they agreed that serving people who are transgender is both within their scope of practice and their ethical responsibility, as well as a medical or educational necessity. Given this large proportion of survey respondents, it can be assumed that professional knowledge positively influences how students and SLPs perceive services to people who are transgender. Thus, graduate training programs should further invest in increasing professional and clinical knowledge.

Many students and SLPs in this study believed services provided to this population are necessary for individuals who are transgender during their transition process. These findings are compelling as services provided to individuals who are transgender are currently classified as an elective service and is also listed under preventive or wellness care (ASHA, 2016). SLPs' knowledge about safe modification of the voice could be applied to helping people who are transgender to have the voice they desire. For example, if individuals who are transgender do not receive professional services to modify their voice, they are at risk for developing vocal pathologies due to laryngeal misuse in an effort to approximate their desired gender identity (Thornton, 2008). SLPs have the skills needed to train individuals who are transgender to modify other aspects of their communication style, including articulation, resonance, intonation, verbal communication, and nonverbal communication (Olszewski et al., 2018). Additionally, people who are transgender experience serious psychological distress at a rate of 39% compared to 5% of the U.S. population (James et al., 2016). It is possible that some of these negative emotions may be experienced as a result of a mismatch between their voice and communication and their gender identity, which may contribute to mental health issues (Byrne, 2007; Dacakis et al., 2013; Davies & Johnston, 2015). Awareness of this potential mismatch could indicate why SLPs believe that it is educationally and medically necessary to provide services to this population.

Limitations

The survey collected self-reported data on professional and ethical issues, which has methodological limitations. There is an opportunity for a variety of potential biases when the primary instrument is self-reporting, including socially desirable responding (van de Mortel, 2008). The data-gathering method of “cold calling” via physically approaching potential survey respondents during a professional conference has its limitations. It does not allow time for depth of thought on these potentially complicated professional and ethical issues or self-reflection of one's own knowledge, training, and attitudes. Furthermore, collecting data from participants at professional conferences could have limited the breadth of participants. Inclusion of a broader representation of participants from the different regions of the United States could allow for direct comparisons of students and SLPs who live in these areas.

Although the length of the survey could be a limitation, the 12-item survey itself was intentionally limited in length in order to increase participation during a professional meeting. There were some limitations in the content of the survey. Knowledge-based questions focused on professional knowledge, in lieu of clinical knowledge. Assessment of training focused on whether respondents had previously received training and their plans for future training and did not address the content and adequacy of the training received. The question related to comfortability in working with people who are transgender did not allow respondents the opportunity to explain the source of their lack of comfortability. Additionally, a question about other personal experiences that were not related to training, such as family and friend relationships with people who are transgender, would have been informative in the survey. The inclusion of qualitative questions could also provide a greater depth of understanding of students' and SLPs' attitudes in serving people who are transgender.

There are several items within the demographic portion of the survey that were not included but that could have added to the quality of the findings. For example, race was not included as a demographic survey question as previous studies did not include race or provide evidence that race was a factor (Hancock & Haskin, 2015; Kelley et al., 2008; Kline, 2015). However, the influence of race on the perceptions of people who are transgender is an understudied factor, and this could be an area of further exploration. The survey also did not include information about the respondents' area of practice. This would have been helpful information in analyzing how the area in which one works might influence their knowledge, training, and attitudes about working with people who are transgender.

Clinical Implications

Although a majority of students and SLPs are knowledgeable that serving individuals who are transgender is within their scope of practice and is their ethical responsibility, there is still a gap in providers with this knowledge. Even though there is a small percentage of graduate schools that do offer training for serving individuals who are transgender, one way to address this self-reported gap could be to teach these services in all graduate schools. Graduate courses in voice and voice disorders or multicultural issues could focus on understanding the scope of practice, ethical responsibility, sensitivity training, and clinical training. This training could be accomplished by guest speakers, virtual seminars by experts, book clubs, or use of current textbooks and manuals that are available (Adler et al., 2012; Olszewski et al., 2018). It is important for students to apply their knowledge in a clinical setting through a transgender clinic or service-learning course.

For the practicing professional, professional development could be offered through virtual seminars, sessions at conferences or conventions, and book clubs that focus on the same topics previously stated. Clinically, graduate schools could serve as a hub for training SLPs in providing clinical training in a transgender voice and communication clinic. Clinical skills could also be learned through face-to-face or virtual mentorship or by implementing a manualized program (Olszewski et al., 2018) in concert with a mentor. Many SLPs believe that providing services to individuals who are transgender is a medical or educational necessity. Because SLPs provide these elective services, it is important that SLPs be compensated for their time. Therefore, practicing professionals should become educated on billing and reimbursement issues.

Conclusions

People who are transgender often seek the services of SLPs in order to communicate their desired gender identity. As an SLP, cultural competence is necessary to provide quality services to the individuals who we serve, including people who are transgender. SLPs need to demonstrate cultural competence within the framework of knowledge, training, skills, and attitudes (Van Den Bergh & Crisp, 2004).

Based on this study, a majority of students and SLPs who responded to this survey displayed an important element of cultural competence in the area of knowledge related to their scope of practice and code of ethics. The survey did not address clinical skills when working with people who are transgender. However, the respondents were aware of their professional role in serving individuals who are transgender in the area of voice and communication and their responsibility in responding to potential referrals. In regard to training, there were approximately 20% of students and SLPs who reported receiving training to serve people who are transgender, with only 8% having actual experience. In terms of attitude, a little more than half of students and SLPs felt comfortable in serving this population, with only 37% planning to seek training in the future. In summary, students and SLPS are working toward cultural competence, but there is room for improvement in the areas of knowledge, training, and attitudes of SLPs regarding the services for people who are transgender.

Future Research

No other study of SLPs' knowledge, training, and attitudes in respect to serving people who are transgender exclusively could be located at the time of this writing. Given the growing popularity and visibility of this clinical area, future research is needed. This study focused on professional and ethical knowledge, both key components of cultural competence. However, future studies should focus on expanding the understanding of SLPs' cultural competence, including their clinical knowledge and skills of how to train the vocal characteristics and function of individuals who are transgender. Additionally, research should include qualitative methods such as interviews or focus groups to analyze the attitudes of students and SLPs. Interviewing a subgroup of participants could provide a more in-depth understanding of knowledge, training, and attitudes that is not possible from a survey alone. Within these interviews, researchers could also explore participants' personal experiences and how they could also influence knowledge, attitude, skills, and training. Qualitative design is helpful because it allows the researcher the opportunity attempt to understand the experiences and actions of participants (Maxwell, 2005). This is necessary given the intertwining of the complicated ethical and professional factors involved with this clinical area.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Mountain West Clinical Translational Research Infrastructure Network (5U54 GM104944) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The authors would like to thank former students and current speech-language pathologists Elena Freeman, Regina Thomas, Ruth Ogbemudia, Kylie Myers, and Kelly Sanderson for their contribution to the development of this project and collection of the data for this research.

Appendix

Survey Questions

I identify as…

What is your age range?

What is your professional level?

How many years of professional experience?

What state do you reside?

Have you had experience treating transgender patients for voice and communication?

Treating transgender voice clients is within my scope of practice as a speech-language pathologist or will be within my scope of practice when I am a speech-language pathologist.

I am comfortable with treating transgender voice patients.

I have received training for working with the transgender population.

I am likely to pursue training for treating transgender voice patients.

Treating transgender clients who are referred to me is my ethical responsibility.

Transgender voice therapy is a medical and/or educational necessity for LGBTQ.

Funding Statement

This research was supported in part by the Mountain West Clinical Translational Research Infrastructure Network (5U54 GM104944) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

References

- Adler R., Hirsch S., & Mordaunt M. (2012). Voice and communication therapy for the transgender/transsexual client: A comprehensive clinical guide (2nd ed.). Plural. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2014). 2014 Standards and implementation procedures for the certificate of clinical competence in speech-language pathology. https://www.asha.org/Certification/2014-Speech-Language-Pathology-Certification-Standards/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Scope of practice in speech-language pathology [Scope of practice]. http://www.asha.org/policy/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2017). Issues in ethics: Cultural and linguistic competence. https://www.asha.org/Practice/ethics/Cultural-and-Linguistic-Competence/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2019a). Voice and communication services for transgender and gender diverse populations. https://www.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589944119§ion=Key_Issues

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2019b). Cultural competence. https://www.asha.org/PRPSpecificTopic.aspx?folderid=8589935230§ion=Key_Issues

- Azul D., Nygren U., Södersten M., & Neuschaefer-Rube C. (2017). Transmasculine people's voice function: A review of the currently available evidence. Journal of Voice, 31(2), 261.e9–261.e23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bralley R. C., Bull G. L., Gore C. H., & Edgerton M. T. (1978). Evaluation of vocal pitch in male transsexuals. Journal of Communication Disorders, 11(5), 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9924(78)90037-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne L. (2007). My life as a woman: Placing communication within the social context of life for the transsexual woman [Unpublished master's thesis]. La Trobe University. [Google Scholar]

- Dacakis G., Davies S., Oates J., Douglas J., & Johnston J. (2013). Development and preliminary evaluation of the transsexual voice questionnaire for male-to-female transsexuals. Journal of Voice, 27(3), 312–320. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S., & Johnston J. (2015). Exploring the validity of the transsexual voice questionnaire for male-to-female transsexuals. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 39(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.05.005 [Google Scholar]

- Flores A. R., Herman J. L., Gates G. J., & Brown T. N. (2016). How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfer M., & Van Dong B. (2013). A preliminary study on the use of vocal function exercises to improve voice in male-to-female transgender clients. Journal of Voice, 27(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfer M. P., & Tice R. M. (2013). Perceptual and acoustic outcomes of voice therapy for male-to-female transgender individuals immediately after therapy and 15 months later. Journal of Voice, 27(3), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock A. B. (2015). The role of cultural competence in serving transgender populations. SIG 3 Perspectives on Voice and Voice Disorders, 25(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1044/vvd25.1.37 [Google Scholar]

- Hancock A. B., & Haskin G. (2015). Speech-language pathologists' knowledge and attitudes regarding lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) populations. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 24(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1044/2015_AJSLP-14-0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James S. E., Herman J. L., Rankin S., Keisling M., Mottet L., & Anafi M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality; http://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS%20Full%20Report%20-%20FINAL%201.6.17.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kelly L., Chou C. L., Dibble S. L., & Robertson P. A. (2008). A critical intervention in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Knowledge and attitude outcomes among second-year medical students. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 20(3), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401330802199567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M. E., Winter S., & Webster B. (2009). Contact reduces transprejudice: A study on attitudes towards transgenderism and transgender civil rights in Hong Kong. International Journal of Sexual Health, 21(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317610802434609 [Google Scholar]

- Kline L. I. (2015). Health care provision to transgender individuals; understanding clinician attitudes and knowledge acquisition (Master's thesis). Proquest. (Publication No. 1570475). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw J. G., & Diaz E. M. (2006). The 2005 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth in our nation's schools. Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network; http://www.glsen.org [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw J. G., Greytak E. A., & Diaz E. M. (2009). Who, what, where, when, and why: Demographic and ecological factors contributing to hostile school climate for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(7), 976–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9412-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landén M., & Innala S. (2000). Attitudes toward transsexualism in a Swedish national survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29(4), 375–388. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1001970521182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masiongale T. (2009). Ethical service delivery to culturally and linguistically diverse populations: A specific focus on gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender populations. SIG 14 Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 16(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1044/cds16.1.20 [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J. A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (2nd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mount K. H., & Salmon S. J. (1988). Changing the vocal characteristics of a postoperative transsexual patient: A longitudinal study. Journal of Communication Disorders, 21(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9924(88)90031-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movement Advancement Maps. (2019). Non-discrimination laws. http://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps/non_discrimination_laws

- Norton A. T., & Herek G. M. (2013). Heterosexuals' attitudes toward transgender people: Findings from a national probability sample of US adults. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 738–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0110-6 [Google Scholar]

- Oates J., & Dacakis G. (2015). Transgender voice and communication: Research evidence underpinning voice intervention for male-to-female transsexual women. SIG 3 Perspectives on Voice and Voice Disorders, 25(2), 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1044/vvd25.2.48 [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski A., Sullivan S., & Cabral A. (2018). Here's how to teach voice and communication skills to transgender women. Plural. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T., German D., & Kerrigan D. (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 84, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers R. S., Suitor J. J., Guerra S., Shackelford M., Mecom D., & Gusman K. (2003). Regional differences in gender—Role attitudes: Variations by gender and race. Gender Issues, 21(2), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-003-0015-y [Google Scholar]

- Refinery 29. (2019). Trans America, How does your state rank on “The civil rights issue of our time”? https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2015/03/83531/transgender-rights-by-state

- Snelgrove J. W., Jasudavisius A. M., Rowe B. W., Head E. M., & Bauer G. R. (2012). “Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: A qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Services Research, 12(110), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor J. J., & Carter R. S. (1999). Jocks, nerds, babes and thugs: A research note on regional differences in adolescent gender norms. Gender Issues, 17(3), 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-999-0005-9 [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. K. (2004). Homophobia, history, and homosexuality: Trends for sexual minorities. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 8(2–3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v08n02_01 [Google Scholar]

- Thornton J. (2008). Working with the transgender voice: The role of the speech and language therapist. Sexologies, 17(4), 271–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2008.08.003 [Google Scholar]

- Transgender Law Center. (2019). Non-discrimination. https://transgenderlawcenter.org/equalitymap

- Turner K., Wilson W. L., & Shirah M. K. (2006). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender cultural competency for public health practitioners. In Shankle M. D. (Ed.), The handbook of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender public health: A practitioner's guide to service (pp. 59–83). Harrington Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel T. F. (2008). Faking it: Social desirability response bias in self-Report research. The Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(4), 40. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Bergh N., & Crisp C. (2004). Defining culturally competent practice with sexual minorities: Implications for social work education and practice. Journal of Social Work Education, 40(2), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2004.10778491 [Google Scholar]

- World Professional Association for Transgender Health. (2011). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people (7th ed.). https://www.wpath.org/publications/soc