Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to generate a theory grounded in data explaining caregivers' understanding of their child's language disorder and the perceived role of speech-language pathologists in facilitating this knowledge.

Method

This study employed grounded theory as a conceptual framework. Qualitative data were generated based on semistructured interviews conducted with 12 mothers of children who had received speech-language pathology services.

Results

The following themes emerged from the data analysis: (a) Many mothers reported receiving confusing or irrelevant diagnostic terms for language disorder, (b) mothers of children with language disorders were distressed about their children's language problems, (c) mothers did not always trust or understand their children's speech-language pathologist, and (d) mothers were satisfied with the interventions their child had been receiving. Mothers described their children's language disorder using a total of 23 labels, most of which were not useful for accessing meaningful information about the nature of their child's communication problem. Generally, mothers reported they did not receive language-related diagnostic labels from speech-language pathologists for their child's language disorder.

Conclusions

Two theories were generated from the results: (a) Lack of information provided to mothers about their child's language disorder causes mothers psychological harm that appears to be long lasting. (b) Difficulties in successfully relaying information about language disorders to parents result in negative perceptions of speech-language pathology. Implications and future directions are discussed.

Supplemental Material

We know little about the experiences of parents and caregivers who are accessing services for their children with communication disorders in general and even less for those procuring services for children with language disorders specifically (caregivers will be referred to as “parents” going forward). Yet, there are reasons to be concerned about families' experiences, specifically as it relates to the role parents play in an evidence-based structure, the need parents have to be informed of service processes, and what parents perceive their role to be in the overall process. Additionally, no information is available describing the disclosure process and what diagnostic terms families receive from practicing speech-language pathologists (SLPs) with regard to their child's language disorder.

At the forefront, parent input regarding their preferences relating to assessment, intervention, and dismissal is a necessary element of evidence-based and clinically effective practice (Buzanko, 2018). Most SLPs and researchers are familiar with the three components of the evidence-based practice triangle (E3BP; Sackett et al., 1996). While the primary focus is placed on the external evidence obtained from outside research and the internal evidence collected through clinical practice, parents' preferences contribute appreciably as the final component to evidence-based practice (EBP). The inclusion of parents' preferences has often been overlooked in the clinical literature (Gillam & Gillam, 2006; Roulstone, 2015; Ruggero et al., 2012). For example, Roulstone (2015) reported that outcome measures that parents value, such as positive experiences and functional outcomes as it relates to accessing services, are not routinely measured in practice or research settings. As Buzanko (2018) aptly stated regarding clinical professionals providing services to families, high value should be placed on parent input because we want to provide speech-language services “for” our clients rather than “to” our clients (see also Griffey, 1989).

In order to provide care that recognizes parents' assessment, intervention, and dismissal preferences as part of E3BP, parents need to be informed of their potential options and then be afforded the time to process the implications of the services they are about to undertake (Dollaghan, 2007). There are reasons to believe that some parents might be unclear about what is taking place over the entire course of their child's visits with an SLP. For example, an independent review of needs and services for children with speech, language, and communication needs (SLCN) in England received 2,000 responses to a questionnaire as part of an action plan to improve intervention services (Bercow, 2008). Five critical themes were identified based on participant responses, including the realization that current systems demonstrate high variability and lack of equity, the importance of joint working, the need for a continuum of services designed around the needs of families, the importance of early identification and interventions, and the salient need for communication between service providers and parents. Specifically, families who suspected that their child had SLCN did not know where to obtain services. Additionally, 77% of respondents stated that the information they needed to support their children with SLCN was either not readily available or was not available at all (Bercow, 2008, p. 20). Some parents also reported that health and education staff were unable to provide information about SLCN because either the staff did not have enough time or they did not have sufficient knowledge to address parent concerns. Findings from this study sample may or may not align with the experiences of parents in the United States.

This gap in EBP extends to what parents understand about their role in the intervention process. Davies et al. (2017) interviewed 14 parents of preschool children with speech and language disorders and documented the changes in the parents' perceptions of their role over the course of intervention. Parents believed in their role as advocates for their children but understood what they were to do as a potential intervention provider to a lesser extent. Importantly, parents expected to learn about being an intervener from the time of their first visit with their SLP. Although Davies et al. was referring to parents' expectations as intervention providers, it is likely that, to participate actively in the E3BP process, parents also need to be educated about their child's language disorder, including receiving basic information about the clinical labels used to characterize language disorders, their common taxonomies, etiologies, and their associated risks.

It is unknown what information parents receive from SLPs about their child's language disorder throughout their participation in services as no previous studies have addressed this issue. The lack of information about the assessment and disclosure process means that we do not know what diagnostic terms families receive for their child's language disorder. This gap in parent's understanding of language disorder influences how parents access information about their child (Schuele & Hadley, 1999). Furthermore, we do not know how SLPs currently approach the disclosure process with families. As a result, it is unknown what families do or do not understand as it relates to their child's language disorder.

Disclosure

Part of the diagnostic procedure is to provide families with the outcomes of the assessment, supply an interpretation of those findings, and present a diagnosis for the point of parental concern. “Disclosure” refers to the first communication provided to parents regarding the diagnosis of disability in their child (Hasnat & Graves, 2000). Numerous studies have addressed the disclosure process in developmental disabilities, with attention focused on parental experiences as relayed through semistructured interviews (Carmichael et al., 1999; Graungaard & Skov, 2006; Hill et al., 2003; Muggli et al., 2009; Sutton et al., 2006; Watson et al., 2011). Although these studies cover a broad range of developmental disabilities (bone dysplasia, fragile X, intellectual disability of unknown origin, cerebral palsy, etc.), research indicates that parents were generally dissatisfied with the disclosure process. The disclosure process of language disorder to parents has not been previously studied. However, there are reasons to believe that parents have interactions that are relatively more positive during the disclosure of language disorder than other types of disorders. One of the notable areas of dissatisfaction from parents of children with developmental disabilities was that the disclosure of their child's disability was not relayed in person by the professional overseeing the assessment (Carmichael et al., 1999; Hill et al., 2003). This situation is unlikely to apply with SLPs working with young children who receive their assessment in early intervention or preschool settings because the SLP is meeting with parents face-to-face to discuss the child's care. However, school settings in the United States may face problems similar to other professions during the disclosure process if SLPs choose not to discuss test results with parents before mailing their assessment findings to families prior to the Individualized Education Program (IEP) meeting.

While many studies have reported high levels of dissatisfaction with the disclosure process among parents of children with disabilities across multiple fields (for a review, see Watson et al., 2011), Hasnat and Graves (2000) reported that dissatisfied outcomes are not inevitable. They interviewed parents of children with developmental disabilities regarding their experiences of the initial disclosure of their children's diagnosis. Their sample reported high levels of satisfaction (82.6%) that included key clinician factors such as providing large amounts of information, good communication skills, a genuine understanding of parent's concerns, and being direct in manner.

There is some evidence to suggest further that, when parents have an informed understanding of the nature of their children's developmental difficulties, this contributes directly to more resilient pathways. For example, Sorensen et al. (2003) examined the psychosocial outcomes of 100 children (ages 7–11 years) referred initially for treatment of their learning disabilities. They found that 2 years of intervention directed at children's academic skills had yielded little improvements in the specific areas targeted. However, in terms of psychosocial outcomes, those parents who felt they had understood their child better as a result of the clinical evaluation reported a significant decline in their child's adjustment problems (especially depression and conduct). This finding suggests that successful assessments are those that do more than list out children's individual strengths and weaknesses for families. Successful assessments are those that provide diagnoses that help parents reframe their understanding of their child's difficulties as being primarily due to factors outside the child's control. In other words, a clear and specific diagnosis of language disorder that parents understand might, on its own, demonstrate a positive therapeutic effect on children's development.

Terminology and Definitions of Language Disorder

Educating parents about childhood language disorders may be problematic for SLPs despite education being one of the foundational components of evidence-based practices. One of the primary barriers to educating parents about language disorders may be the profession's lack of an agreed-upon operational definition of language disorder. There are numerous terms to describe language disorders in general as well as specific subtypes. Language symptoms have also been conceptualized in a variety of ways that include discrepancy criteria based on standard score cutoffs, clinical markers aligned with psycholinguistic phenotypes, as well as impacts on functional communication and academic success (Bishop, 2014; Paul et al., 2018; Rice, 2003; Tomblin, 2006). Variation in operational definitions is complicated further by the lack of shared terminology across settings, clinicians, and researchers referring to cases of idiopathic language disorder in children. There are also recognized differences between the fields of education and speech-language pathology (Gallagher et al., 2019).

A second barrier to educating parents about language disorders may be rooted in the reality that language disorder often represents a “hidden disability” (Conti-Ramsden et al., 2014). In other words, widely agreed-upon clinical characteristics of language impairment, such as difficulty with morphosyntax and verbal working memory, are not overtly obvious to parents (Christopulos & Keen, 2019). Language disorders may not be recognized as an actual disability outside the clinical context, despite being among the most prevalant neurodevelopmental disorders in children (approximately 7%; Rice, 2017). As a result, parents may have a difficult time understanding why their child is struggling to keep up with their peers. This confusion may be especially true when children do not have concomitant deficits in other areas of development (e.g., nonverbal IQ, behavior). Many parents of children with developmental disabilities embark upon a journey to find a specific diagnosis that they believe will help them access treatment, intervention, and social support (Gillman et al., 2000). However, if the disorder is not easily recognizable, parents will likely struggle to uncover the true nature of their child's disability accurately.

A variety of terms have been used to describe linguistic deficits in children, further complicating the issue of parental education. Formal terms include “language disorder” in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013) as well as “expressive language disorder” and “mixed-receptive expressive language disorder” in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th Revision, Clinical Modification and Related Health Problems (World Health Organization [WHO], 2015). However, some of the key terms that have been used to describe language disorder, long recognized by SLPs and researchers alike, have not yet been incorporated into formal clinical taxonomies. Specific language impairment (SLI) has been used for decades by researchers to describe cases of language disorder with unknown etiology and is the most commonly used term to describe this group of children in the literature (Bishop, 2014). While SLI has been frequently used in research reports, some have raised questions about the suitability of SLI as a clinical label. Concerns expressed include the possibility that the exclusionary criteria associated with SLI might be misused to prevent some children who would benefit from speech-language pathology services from receiving them (Reilly et al., 2014). However, this risk probably varies across countries and different service delivery systems (Volkers, 2018). Recent efforts have been made to reach an international consensus on terminology across professionals and heighten public awareness of language disorders. The CATALISE Consortium, a multinational group of 57 English-speaking individuals with expertise in language disorders, recommended the term “developmental language disorder” for cases of language disorder without an associated biomedical etiology (Bishop et al., 2017). It appears that this term is likely to be more widely applied going forward in research reports and public awareness campaigns. Despite current discussions regarding the relative benefits of different clinical designations, it remains unknown what terms SLPs have been using when they disclose to families that they have identified a language disorder.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative research methods have been used frequently to investigate the experiences of families with children who have developmental disorders. Semistructured interviews used in qualitative methods provide an investigation of the experiences of individuals as socially embedded phenomena (Damico & Simmons-Mackie, 2003; Simmons-Mackie, 2014). Qualitative methodologies have been used within the field of speech-language pathology to investigate the experiences of those with various communication disorders (e.g., fluency, aphasia, language impairment) and are considered a valuable methodology that incorporates the voices of vulnerable groups into research that affects them (Lyons & Roulstone, 2018; Twomey & Carroll, 2018). Because there is no documentation in the literature about what parents of children with language disorders understand about their child's diagnostic label(s) and other elements of the disclosure process, this study employed the qualitative method of grounded theory. Most quantitative methods focus on testing a priori hypotheses surrounding a particular problem or issue, whereas grounded theory is a method of generating a theory induced from the information gathered throughout the interview process (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Grounded theory aligns with the three tenets of symbolic interactionism: human beings act toward things (e.g., physical objects, ideas, individuals) based on the meaning that things have for that individual, the meaning of things is a result of the social interactions of the individual, and individuals go through an interpretive process when they deal with the things they encounter (Blumer, 1962). Several elements of symbolic interactionism were applied to this study. Within the symbolic interactionist framework, for example, individuals come to their understanding about their world through their own interpretation of their experiences during social interactions (Hutchinson, 1993). Therefore, the interactions that parents have with the SLP during the assessment, disclosure, and intervention processes would directly influence the parent's interpretation of their child's language disorder.

Study Purpose

Our review of the literature found that the disclosure process of language disorders to parents has not been previously studied. The interactions between SLPs and parents may play a critical formative role in how parents conceptualize their child's language disorder. Therefore, utilizing semistructured interviews, we investigated the experiences of mothers regarding their disclosure experiences and subsequent discussions with SLPs about their child's language disorder. Specifically, the purpose of this study was to generate a theory grounded in data that attempts to explain mothers' understanding of language disorder and related diagnostic terminology.

Method

Approval for this project was granted by The University of Utah Institutional Review Board. Written consent was obtained from each participant prior to their participation. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (Tong et al., 2007) reporting guidelines for qualitative research. The 32-item checklist associated with these criteria is presented in the Appendix.

Recruitment and Sampling

A mixed sampling method was used to recruit participants into the study, including convenience, judgment, and theoretical sampling strategies (Marshall, 1996). Participants were recruited from a convenience sample of a group of mothers of children whose profiles were consistent with research criteria associated with SLI and accordingly did not present with any comorbid conditions (N = 41). These children represented a subgroup from a larger study sample used to investigate the effects of co-occurrence of language disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on children's linguistic symptoms relative to the presence of language disorder alone (Redmond et al., 2015, 2019). From this SLI subgroup of children with empirically validated SLI, mothers were purposefully and theoretically recruited into the study following data collection and coding following qualitative methods (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Emmel, 2013; Marshall, 1996). Theoretical sampling is used to generate theory, such that the recruitment process is controlled incrementally by themes emerging from the data rather than being prescribed by an a priori power analysis or other quantitative technique using modestly informed guesses about the expected levels of variability (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). Participants are recruited based on the potential diversification of conceptual categories, resulting in a more comprehensive theory generation. This method is different from quantitative recruiting methods where the goals are either hypothesis testing or the verification of previous findings, which benefit from a homogeneous sample. Therefore, the first two mothers who participated in our study were randomly recruited from the convenience sample. Once their interviews were coded, nine additional mothers from the convenience sample were approached based on the possibility that they might provide information divergent from what had been provided by the previous participants (e.g., selected by age, education, or race). In the interest of further collecting potentially divergent views, we also recruited an additional mother into our study sample whose child was not from the convenience sample. This child was also considerably older than the other children.

Participants

Twelve mothers of children who had received speech-language pathology services participated in the study. Eleven of the 12 participants were recruited from a larger sample of families who had taken part in a previous investigation (Redmond et al., 2015). Mothers were approached to participate in this study if their child had been receiving speech-language services or had a Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition (Semel et al., 2003) standard score at or below 85, and had a nonverbal cognitive standard score at or over 85 (Naglieri Nonverbal Achievement Test; Naglieri, 2003). Because of their participation in the previous study, 11 of the 12 participants had met the interviewer in person prior to their participation in this study. Participant 108 was not involved in the authors' previous studies but became a participant after hearing of the study through a community contact. Although test scores were unavailable for this participant, the individual was included to expand the diversity of the sample. Table 1 provides demographic and standardized language performance for the children of the participants. Standardized language tests included the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition (Semel et al., 2003) and the Test of Early Grammatical Impairment (Rice & Wexler, 2001). Scores from the Naglieri Nonverbal Achievement Test (Naglieri, 2003), a nonverbal test of cognitive abilities, were also provided. All the children discussed in the interviews had received speech-language services at some point in their education, and the majority (75%) were receiving speech-language services when the mothers were interviewed. Most of the children in the study received their first assessment from publicly provided early intervention services. Two of the mothers reported receiving their assessment at Headstart, whereas eight of the mothers received early intervention through their local school districts either from birth to age 2 years or other early intervention preschool programs. Two mothers did not share where their child received their first evaluation (see Table 1). Most of the children had received an evaluation during preschool attendance (2–4 years), although two mothers did not report the age at which their child was first assessed.

Table 1.

Child characteristics.

| Code | Child's age a | Child's sex | Child's race/ethnicity | Child's CELF-4 b | Child's TEGI screener b | Child's NNAT b | Place of initial assessment | Age of initial assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 7 | Boy | White | 97 | 78 | 129 | Headstart | Preschool |

| 102 | 5 | Girl | White | 56 | 56 | 92 | Public education preschool | 3.5 years |

| 103 | 5 | Boy | White | 67 | 27 | 122 | Public education preschool | 3.5 years |

| 104 | 14 | Girl | Hispanic/Asian | 50 | 73 | 96 | Public education preschool | 3 years |

| 105 | 6 | Girl | White | 40 | 29 | 90 | Not reported | Not reported |

| 106 | 6 | Girl | White | 81 | 94 | 103 | Public education preschool | 4 years |

| 107 | 9 | Boy | White | 79 | 100 | 87 | In home early intervention | 2 years |

| 108 | 22 | Boy | White | NA | NA | NA | Public education preschool | Preschool |

| 109 | 9 | Boy | Asian | 82 | 95 | 112 | Headstart | Preschool |

| 110 | 6 | Boy | Asian | 99 | 95 | 115 | Not reported | Not reported |

| 111 | 9 | Boy | White | 78 | 87 | 125 | Public education preschool | Preschool |

| 112 | 8 | Girl | White | 52 | 3 | 87 | Public education preschool | 4 years |

Note. CELF-4 = Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals–Fourth Edition; TEGI = Test of Early Grammatical Impairment; NNAT = Naglieri Nonverbal Achievement Test; NA = not administered.

Ages are presented in years.

Scores are presented as standard scores (M = 100, SD = 15).

The participants were aware of the interviewer's interest in children with language disorders. All the children discussed in the interviews were monolingual English speakers. One mother was an English and Spanish speaker, whereas the remaining mothers were monolingual English speakers. Participant education level is presented in Table 2. Notably, there was a wide range of education levels in this sample, including high school completion to the attainment of advanced graduate degrees. The language abilities of the mothers were not examined, but it is possible that some of the mothers had their own language impairments or learning disabilities. Participants also represented a wide age range (Mdn = 37 years, first quartile = 36 years, third quartile = 44 years, range: 29–50 years). The length of the interviews ranged from 16 to 53 min (M = 22.50, SD = 10.39), as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Maternal characteristics.

| Code | Age (years) | Education level | Length of transcript (words) | Length of interview (min/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 101 | 37 | Technical degree | 2,611 | 20.56 |

| 102 | 36 | Bachelor's degree | 9,001 | 53.02 |

| 103 | 37 | Some college | 4,323 | 18.17 |

| 104 | 39 | Master's degree | 2,201 | 20.47 |

| 105 | 29 | High school | 1,277 | 16.31 |

| 106 | 43 | Some college | 3,129 | 18.07 |

| 107 | 37 | Some college | 3,479 | 25.52 |

| 108 | 50 | PhD | 3,468 | 19.36 |

| 109 | 36 | Some college | 2,885 | 16.17 |

| 110 | 47 | Bachelor's degree | 1,874 | 16.09 |

| 111 | 44 | Bachelor's degree | 2,223 | 17.17 |

| 112 | 46 | Bachelor's degree | 4,952 | 29.14 |

A mixed-method (convenience, judgment, and theoretical) sampling strategy was used (Breckenridge & Jones, 2009; Charmaz, 2006; McCann & Clark, 2003), such that participants were recruited into the study who had the potential to add their unique perspectives of their child's language disorder. During recruitment, none of the families who were approached declined to participate in the study. Interview data were concurrently coded with constant comparison across interviews with additional participants recruited once previous data indicated that theoretical saturation had not been achieved and that new themes brought in by new participants were emerging from the data. Theoretical saturation, the point at which no new themes emerged from the data, was reached after 10 interviews (Charmaz, 2006; Higginbottom, 2004). Two additional interviews were conducted that confirmed information redundancy.

Data Collection

Data for this study consisted of semistructured qualitative interviews that took place in the participant's home or office (n = 3), over the phone (n = 1), or at the Child Language Laboratories at The University of Utah (n = 8). The primary purpose of the interview was to investigate the terminology SLPs had used to describe children's language disorders to their parents. The secondary purpose of the interview was to uncover the experiences parents had with the disclosure process. Interviews were conducted by the first author and were digitally recorded for later transcription. Only the interviewer and the participant were present during the interview. Participants were asked to respond to open-ended statements that were provided by the examiner. During the interview, the interviewer took field notes indicating whether the participant had provided information relevant to the statements that had been provided. Planned prompts were used when the participant did not respond to the statement or did not provide basic information about their experience. Statements and their associated prompts are provided in Table 3. If the examiner did not understand the response, additional information was requested with the prompt, “Tell me more about X.”

Table 3.

Interview questions.

| Statement | Prompts |

|---|---|

| 1. Tell me about your child and your child's language development. | a. Tell me how you knew your child's language development was different from other children. b. Tell me about when you began to think that your child needed help with their language. c. Tell me about your child's behavior, particularly about their social and emotional behaviors. |

| 2. Tell me about when your child was diagnosed with language difficulties. | a. Tell me about your child's language assessment. |

| 3. Tell me about your child's diagnosis. | a. Tell me about how your child's diagnosis was explained to you. |

| 4. Tell me about information you have gotten about your child's diagnosis. | a. Tell me about what information was or was not helpful to you. |

Research Design

This study employed Glaserian grounded theory as its conceptual framework (Glaser, 1965; Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which has an inductive and exploratory focus. One goal of Glaserian grounded theory is to identify a core category or set of relationships between categories that are associated with the topic that assists researchers in generating a theory to account for observed variation (Glaser & Holton, 2005; Skeat & Perry, 2008). The goal of this study was to uncover potential parental preferences in language disorder diagnostic terminology and to uncover general information regarding the parental experience of going through the diagnostic process with an SLP.

As part of the Glaserian methodology, those conducting research avoid reading any material on the topic under investigation prior to data analysis to avoid researcher bias during coding and data analysis (Glaser, 1978). The first author did a preliminary literature search on the topic for the institutional review board application, whereas other literature reviewed at this stage focused upon qualitative methodology only. Research assistants participating in the study received information regarding the general purpose of the study but were not provided with any literature concerning the topic. The first author collected articles on the topic of diagnostic labels while data collection was taking place, but most of the literature presented in this report was not examined until after data analysis had been completed.

Interview Transcription and Coding

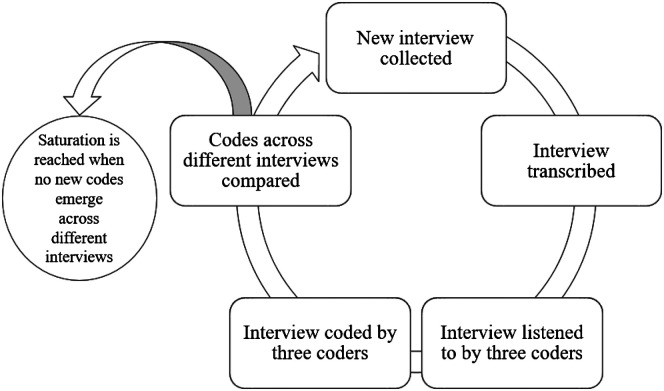

Five research assistants and the first author were involved in transcribing and coding the interview transcripts. The research assistants included three undergraduate students and two doctoral students at The University of Utah Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders. Transcriptionists met a reliability level of 85% on transcribed words from child language samples prior to transcribing the maternal interviews, and every coder listened to each interview prior to the assignment of codes to ensure the accuracy of the transcription. Interviews were transcribed orthographically and verbatim. Therefore, the transcripts of the interviews included mother's dysfluencies (captured in parentheses), unintelligible words (denoted by an “X” in the utterance), and potentially ungrammatical productions. Figure 1 demonstrates the process by which interviews and coding were addressed.

Figure 1.

Interview and coding cycle.

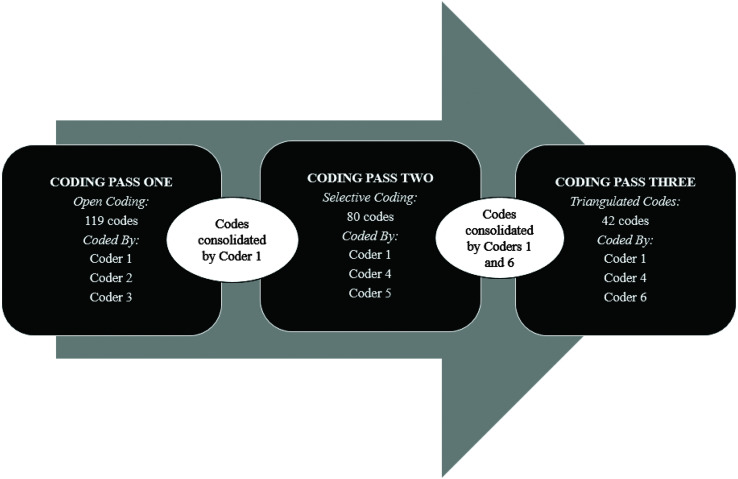

Interviews were coded according to grounded theory's constant comparison method using HyperRESEARCH software (HyperRESEARCH 3.5.2, 2013). Open coding was used during the first phase of coding the transcripts, which means that coders generated their own labels for ideas, emotions, and concepts expressed by the mothers. Three coders, two undergraduates in speech and hearing science and one of the authors, used their own inductive reasoning to arrive at a provisional label. Coders used labels that may have been one word or a sentence to describe their interpretation of the data. At this level of coding, every utterance produced by the mothers was conceptually identified and labeled independently by each coder, excluding one-word utterances. At this stage, an utterance could be assigned multiple labels by a coder to capture various messages conveyed by the mothers. Once the first two interviews were transcribed and coded independently by all three coders, constant comparisons of the interviews were conducted (see Figure 1). Constant comparison, completed by the first author, consisted of comparing themes across the coded interviews to determine whether any new themes were emerging. If new codes emerged from the interview, including codes that were not similar in theme to previous ones, then an additional participant was recruited into the study. Open coding and recruiting into the study continued until theoretical saturation was achieved, as indicated by the absence of new codes (Glaser, 1978).

A total of 119 different open codes were independently generated during the first coding pass by the three coders. Figure 2 displays the coding process and the points at which codes were consolidated. Codes were consolidated after the first coding pass based on their overlapping properties. Thus, the first coding pass can be characterized as the process of leveling out synonyms across different coders. Selective coding followed, which involved combining individual codes into preliminary hierarchical structures. Eighty selective codes captured the categories generated during the open coding process (see Supplemental Material S1 for open source and selective coding lists). In order to address maternal statements that did not fit into our code reduction, the code “question on coding” was added. This code was used as a temporary placeholder during this process when coders did not feel confident that any of the available selective codes successfully captured the intent of the mother's statement, which happened on five occasions. In each case, a new code was successfully added to the set. During the second round of coding, three coders (one undergraduate student in speech and hearing science, one doctoral student in speech-language pathology, and one of the authors) coded each transcript independently using the selective codes.

Figure 2.

Coding process.

Codes were consolidated a second time (by Coders 1 and 6) to create a final list of 42 codes. Once these codes were completed, three coders (one undergraduate student in speech and hearing sciences, the first author, and the second author) independently assigned codes from the final list to the parent utterances, triangulating the final coding. Initial reliability among the three coders on the third pass using the final list was 88.93% (265/298). Consensus coding was then completed on disagreements, resulting in a final agreement level of 97.32% (290/298). In summary, each transcript was coded 9 times across three rounds of iterative coding involving six individual coders. Figure 2 summarizes the coding process, including the type of coding that occurred and the identities of the coders that completed each pass.

Prior to beginning the third coding pass, the first two authors and the graduate research assistant completed a disclosure process. Each coder completed a self-reflection of their professional and personal experiences with people who had communication disorders and discussed potential biases they may have surrounding the topic of providing diagnostic labels for individuals with language impairment. Each coder (1, 4, and 6) wrote about their personal and professional experiences with those with communication disorders. These experiences were then discussed as a group in order to protect against potential biases entering the coding of the data. Self-reflection represents an important step in qualitative research as a method to control for biases that may occur in the data because of the individual experiences and theoretical orientations of the coders (Elliot et al., 1999). The first coder was a female with a research doctorate in child language who had worked for 16 years on assessment issues in language disorders. The second coder was a male doctoral student in speech-language pathology who was completing his clinical fellowship year in junior high and high schools. The final coder was a female undergraduate student in speech-language pathology who had an adult son with autism spectrum disorder and, as a result, had personally participated several times in the diagnostic and IEP processes.

Results

Interviews

Interviews and their analyses took place over a 3-year span. Analyses of the interviews revealed that the median interview length in the number of words produced by participants was 3,007, with a range from 1,277 to 9,001 (first quartile = 2,201, third quartile = 3,479). The median duration of interviews was 18.17 (min/s), with a range from 16.09 to 53.02 (first quartile= 16.31, third quartile = 20.56). See Table 2 for individual details.

Themes

Four themes with corresponding subthemes emerged from the data analysis. Table 4 presents an overview of the themes and subthemes. The first theme we identified was Many mothers reported receiving confusing or irrelevant diagnostic terms for language disorder. Mothers reported the terms or information they had received to describe their child's language disorder. The second theme was Mothers of children with language disorder were distressed about their children's language problems, in which mothers described their thoughts and concerns surrounding their child's language disorder. The third theme was Mothers did not always trust or understand their children's SLP. In this theme, mothers expressed their uncertainty over their child's diagnosis, difficulties understanding the information they had received, and a sense of disconnect between their values and those of the SLP. The final theme identified was Mothers appeared satisfied with the services their child had been receiving from their SLP. Each theme and subtheme and supporting segments from participants' interviews are discussed below.

Table 4.

Themes and subthemes.

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| 1. Many mothers reported receiving confusing or irrelevant diagnostic terms for language disorder. | |

| 2. Mothers of children with language disorder were distressed about their children's language problems. | 2.1. Mothers felt responsible for their children's language difficulties. |

| 2.2. The assessment process was emotionally difficult. | |

| 2.3. Mothers were concerned about their child's general education. | |

| 2.4. Mothers were concerned about their children's future. | |

| 3. Mothers did not always trust or understand their children's SLP. | 3.1. Mothers expressed uncertainty over the diagnosis. |

| 3.2. Mothers did not understand the information provided about their child. | |

| 3.3. Mothers saw a disconnect between their views/values and the SLP's views/values. | |

| 4. Mothers appeared satisfied with the speech-language pathology services their child had been receiving. |

Note. SLP = speech-language pathologist.

Theme 1: Many Mothers Reported Receiving Confusing or Irrelevant Diagnostic Terms for Language Disorder

One goal of this study was to examine what diagnostic labels parents had received from SLPs to describe their children's language symptoms. Mothers described their children's language disorder using a total of 23 labels, 11 of which were nonoverlapping (see Table 5). Eight (72%) of the labels that were provided could be classified as non–language related (e.g., cognitive delay, apraxia, reading, learning disability, speech, communication disorder, Asperger syndrome, and ADHD), with three of the labels specific to language symptoms (language problem, SLI, and non-specific language impairment). Generally, the labels that were provided to mothers that related to language were neutral descriptors of language or either nonclinical general learning problems that did not belong to any formal diagnostic criteria such as what might be provided in ICD codes or under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; ICD, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification and Related Health Problems; World Health Organization, 2015).

Table 5.

Diagnostic terms provided.

| Code | Diagnostic terms |

|---|---|

| 101 | Speech, learning problem, potential attention-deficit disorder |

| 102 | Speech, cognitive problems |

| 103 | Apraxia, Asperger's (ruled out later) |

| 104 | Specific language impairment |

| 105 | Speech |

| 106 | Speech, reading |

| 107 | Delayed speech |

| 108 | Specific language impairment, non-specific language impairment |

| 109 | Speech, language, learning disability |

| 110 | Speech delay, cognitive delay, communication disorder |

| 111 | Speech, reading |

| 112 | Speech, language problem |

Notably, none of the children of the participants had documented comorbid conditions (e.g., ADHD) at the time that the interviews took place. They also were rated by their mothers as being within normal limits on standardized behavioral rating scales. Standardized nonverbal IQ test scores collected over the course of our research projects confirmed further that none of the children of the participants presented with cognitive deficits. For those mothers who had received descriptions of their children as having “cognitive delay/problems” (Child 102 and Child 110), their children's scores were well within the average-to-high-average range (standard scores = 94 and 115, respectively). The mother of the child who had received a diagnosis of “non-specific language impairment” reported their SLP used this term instead of “SLI” because the child had also been diagnosed with strabismus, a misalignment of the eyes. This is an example of a condition that would not preclude the assignment of SLI as conventionally used by researchers but would be consistent with an overly literal interpretation of the “specific” qualifier in SLI. The mother of the child reported as having “SLI” disclosed that she knew the label applied to her child as a result of coursework she had completed during her graduate program.

Generally, mothers reported that they did not receive diagnostic labels related to language from SLPs over the course of their child's participation in speech-language services. The following statement summarized the assessment experience reported by many of our participants regarding the perceived avoidance of professionals labeling their children's language difficulties:

So basically I want to say that with our first IEP meeting I specifically asked, I'm like, is she autistic? Like, what exactly does she have? I wasn't given anything else so I didn't know. So does she have a learning disability? To this day I am probably still very confused on exactly what exactly she was labeled with. (102)

Theme 2: Mothers of Children With Language Disorder Were Distressed About Their Children's Language Problems

Participants reported their emotional distress when they learned of their child's language difficulties during the initial clinical assessments. One mother stated, “And I thought, oh my goodness, how are we going to get her where she needs to be? Is this serious? Is this not serious? I mean how much time and effort do I need to put into this so that she is successful?” (104) This statement conveyed not only distress about the language problems but also the parent's uncertainty over the diagnosis and concern from the parent over their ability to help their child in the future.

Four subthemes emerged from mothers' reports when they discussed the revelation of their child's language disorder.

Subtheme 2.1: Mothers felt responsible for their children's language difficulties. Mothers reported feeling responsible for their children's language struggles and questioned their parenting skills as a result. Many of the mothers questioned the quantity and quality of time they had spent with their child. Comments from mothers included the following:

I think more it's just I always look back thinking I should have done more. (111)

I feel like when she grows up she's going to say my mom had dyslexic. She didn't read too much to me. (105)

It's hard not to get emotional because you know and they're in there like, well this is what's wrong and this is what's wrong and this is what's wrong. And you're like, okay, what did I do? (109)

The burden of feeling responsible for their child's language disorder left some mothers feeling negative about themselves:

I also feel like a shithead. It's sad. It's, you think, what did I do wrong? What have I done wrong? What should I be doing? And you just think a lot of different things of as what as a parent, you know could have done different. (102)

Time did not appear to diminish mothers' initial feelings of responsibility and guilt.

Without exception, our participants had procured speech-language pathology services for their child at least 2 years prior to their interviews. However, mothers reported their feelings in both the past and present tense, indicating that, for many, their feelings of inadequacy and guilt continued.

Subtheme 2.2: The assessment process was emotionally difficult. For many mothers, the assessment process was characterized as emotionally exhausting. Although mothers had sought out language assessments because of their concerns about their child's development, mothers were distressed upon receiving confirmation from an SLP that their child was not typically developing. We found that intense emotional reactions were common among mothers participating in the assessment process.

And so when I first came home from her being tested at the district that was just, oh I was in bed crying for hours and hours and hours. (102)

A potential contributor to the emotional distress may have been that mothers did not comprehend the nature of the assessment process fully. For example, mothers did not appear to understand how standardized testing works (e.g., interpreting standard scores, examining basal and ceiling levels of performance) or that the language weaknesses of the child would be discussed during the meeting with the IEP team.

It was horrible. It was horrible because, I guess for some other reason I thought well, this test that how they were administrating it was so hard. (112)

Most participants in this study did not receive a diagnostic label related to language during the child's initial assessment for speech-language services. Regardless, the assessment process itself was agonizing for most mothers. The language assessment was the first moment many mothers realized that their child's communication was atypical to the extent that professional intervention was necessary.

Subtheme 2.3: Mothers were concerned about their child's general education. Mothers worried about their child's ability to function in a general education setting with teachers that may or may not understand their child's communication limitations. In order to avoid difficulties, mothers reported that they regularly met with teachers to ensure the teachers understood the nature of their student's communication impairment. These meetings included describing their child's communication difficulties and describing behaviors displayed by the child that indicated that they did not understand what was taking place in the classroom.

So I always played a very active role in trying to work with the teachers and help at home. And I always sent them an e-mail at the beginning of the year saying, let me tell you about my child. And I think here's where he's gonna have problems in your class because here's his problems. And if there is anything we can do please let us know. We want to be supportive. (108)

Despite the discussions mothers had with teachers about their child's language disorder, some teachers continued to have difficulties modifying their communication or instruction to the level needed by the child. Mothers' concerns about their children's ability to function in educational settings prompted mothers to advocate for appropriate levels of instruction on behalf of their child. Mothers felt that they had to “fight for their child.” This advocacy took multiple forms, including intervening when interactions with the teacher were difficult for the child and actively pursuing appropriate accommodations that were not being provided by the educator.

Subtheme 2.4: Mothers were concerned about their children's future. Mothers voiced concerns indicating that they understood the potential negative impact of language disorder on important future social, academic, and occupational experiences: “I was very worried and felt like that factor goes into their future” (110). For example, they worried about their child's ability to navigate potential negative peer interactions. Mothers also expressed apprehension about their child's ability to enter the workforce as an adult with a sustainable career.

The second theme captured many areas of parental distress and highlighted the reality that the emotional burden of parenting a child with language impairment is ongoing. Mothers of children with language impairment experienced high levels of stress when they received the information that their child was not developing typically. The feelings of guilt and responsibility expressed by the mothers continued years after the initial disclosure. Finally, mothers felt obligated to intervene with teachers on their child's behalf in educational settings and worried about how their child would cope socially, academically, and occupationally in the future. Additional quotes illustrating these themes are displayed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Theme 2 with subthemes and illustrative quotes.

| Themes | Subthemes | Illustrative quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Mothers of children with language disorder were distressed about their children's language problems. | 2.1. Mothers felt responsible for their children's language difficulties. | Mother 104: And I took a lot of this guilt and blame on myself thinking, it must be my parenting skills. Maybe I don't talk to her enough and maybe I don't take her to the zoo enough. I just thought \that there was more on my part that I should've been doing as a mother. |

Mother 107: It was hard for me to accept, both ways, because I've I don't know it was it was really hard for me. It was a hard decision for me to accept that and get help for him. It's mainly on my side of the family, I had my parents and people I would talk to about it, and my mom and everyone just, (oh mine mine was) my kid was the same way and they'll just grow out of it and it was fine. And then I had mixed feeling because I personally as a parent, sorry, it still hits me. (um) I kind of almost felt like a failure as a parent. I'm like, what more could I or should I have done to help him with his speech? um like, was I not reading enough to him? Was I not giving him enough time? And so I just, as a parent felt like a failure, and that was a really hard thing for me to accept that it wasn't my fault. |

| 2.2. The assessment process was emotionally difficult. | Mother 103: So I was just very discouraged and I left the school sobbing ‘cause you just feel so helpless and there's no tools given to you. |

Mother 104: Honestly, it was a really confusing time for me. I was not familiar with IEPs so I wasn't really sure what to expect and it was quite devastating, that first meeting just to hear how far behind she was in her language. I left out of there in tears. |

|

| 2.3. Mothers were concerned about their child's general education. | Mother 107: There's still a few things that he's working on that I have to let his teachers know. Like, in his schoolwork if he doesn't understand or comprehend what the teacher wants him to do, he doesn't speak up. And he just sits at his desk with his hands folded and he'll just kind of look around and he doesn't finish his tasks. I had gone in and I had talked to the teacher and said, you know this is a problem he has. He has a hard time with it. |

Mother 110: When he was in preschool…once I walk in pick him up they were giving him a time out. And I'm okay with timeout…. I'm okay with that but then they were lecturing him and they were saying how disrespectful he was and I say he didn't even understand what you're saying…. Some of even the good ones they talk, they don't look at them, and then they just give instructions and then expect him to understand on the side. |

|

| 2.4. Mothers were concerned about their children's future. | Mother 111: So I look forward going, I really hope by junior high you know, because that's almost more what I'm worried about…kids create stuff by then you know to be cruel sometimes, but I'm just hoping his confidence is such that it's not a big deal. |

Mother 108: They didn't do a whole lot of transition planning to adulthood and career or trade or anything. And they probably they could have done more of that…. But you know the worry is what's he gonna do ‘cause if he doesn't get his reading up enough to get into a trade he's gonna be unskilled labor all his life and that's where that's a worry. |

|

Note. IEPs = Individualized Education Programs.

Theme 3: Mothers Did Not Always Trust or Understand Their Children's SLP

Some mothers spoke of their distrust of the information provided by their child's SLP. Sometimes, this distrust was the result of mothers receiving conflicting information from multiple professionals.

And when I went to the speech pathologist at the school district and I told her these things (from the other SLP) and she shut me down, I thought, “Is my other SLP crazy?”

Is this not true? You really start to have doubts about who's telling you the truth and who's not telling you the truth. (102)

Other issues arose centering on the uncertainty over the diagnoses the mother had received, mothers not understanding the information provided by the SLP, or a disagreement regarding their child's intervention.

Subtheme 3.1: Mothers expressed uncertainty over the diagnosis. Most of the mothers in the study did not receive a recognizable diagnostic label for their child's language disorder. This was troubling to mothers who questioned whether the SLP understood the nature of their child's problem. The lack of a formal diagnosis resulted in mothers wondering if their child's SLP knew what was wrong with their child: “Like have we ever, you know, since then have we ever been told exactly what, I still don't know. And I'm not sure if they even know, you know?” (102).

Subtheme 3.2: Mothers did not understand the information provided about their child. Mothers felt confused by the information they had received from the SLP about their child's language performance. Tests scores were one of the few topics explained to mothers, yet mothers did not seem to understand their child's performance due to the SLP's use of unfamiliar terminology. Some mothers attempted to explain their child's language performance on standardized tests during the interview but struggled to explain the scores as relayed to them by the SLP. In the following example, it is unclear whether the mother was referring to the child's percentile rank or standard score, which would result in drastically different interpretations.

There are things that I don't think they are helpful that it just went over my head. I think there were some specifics. I do remember his expressive was like 65th percentile, which is if the average is 100 and he was 65. And his receptive is actually higher. I think 70. No I got it reversed. So he can speak more which is higher. So 70 percent about expressive and about 60 percent of the receptive so his weakness is more on the understanding side. (110)

Generally, mothers were frustrated when they received vague or incomprehensible information.

They told me that she can do things, do squares, like numbers and stuff. But she has to think about it. But they don't tell you where she, they tell you where she's at but she's not there, you know? (105)

Subtheme 3.3: Mothers saw disconnects between their views/values and the SLP's views/values. Mothers had expectations and beliefs about their child that did not always match the recommendations and decisions they received from the SLP. One disconnect was the level of concern demonstrated by the SLP about the severity of the child's language problem. Mothers relayed their frustration that their child's SLP did not consider test results or recommendations from other professionals, whether that professional was a psychologist, audiologist, or another SLP. A final issue raised by mothers was that the SLP did not always understand how the child was developing and what the child needed to be successful. At times, this translated into goals that the mothers did not feel were important to the life of their child. The differences between mothers and SLPs also manifested when it came time to release children from services. Additional quotes illustrating these themes are displayed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Theme 3 with subthemes and illustrative quotes.

| Themes | Subthemes | Illustrative quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3. Mothers did not always trust or understand their children's SLP. | 3.1. Mothers expressed uncertainty over the diagnosis. | Mother 112: I have to ask myself, you know, is what they're telling me, is this true, you know my kid's at late development, I don't know. Late developer whatever you want to call it so with that diagnosis I was kinda like, I'm not too sure about that. Is it my kids are the late developing or, I don't know. So I guess that diagnosis was kinda hard for me to take, because I'm not so sure if they're telling me the truth or not. |

Mother 108: And so oddly enough I kept in touch with my child's first SLP from when he was enrolled in an Early Intervention Program. And she said “I think you need to take her to a neural psychologist.” So I took my child to a neural psychologist in first grade and he freaked me out…(name redacted). And he said {um} I need to call and IEP meeting. We need to have the school principal there. All of her teachers need to be there because kids like yours fall through the cracks and {um} research shows that when they grow up that (you know) they struggle in life. They don't have a good job. They (you know)> Just kind of a snowball effect for the rest of their life. So I thought “oh gosh. What do I do?” (So) so I called the IEP meeting (and) and (they kind of) they kind of blew it off. They didn't think it was as serious as what the doctor had explained it to me. |

| 3.2. Mothers did not understand the information provided about their child. | Mother 104: She didn't ever really explain anything other than the test results. I remember her going over the test results and I didn't understand the bell curve and index scores and so I wasn't quite sure what she was saying and so I know that I had to take the information that she gave me home and kind of process it. Because I felt like I just didn't have a good grasp on that. It wasn't explained to me that she has a language-learning disability. It was just, “These are her scores. She struggles with expressive language and comprehension.” It wasn't very detailed. |

Mother 109: Well you get like three or four papers, it almost looks like newspapers. And they want you to read them, but it's all the jargon, you know what I mean? My husband has a master degree and I have college and I mean, I never graduated but neither of us are stupid. That sounds rude, but like it's just a bunch of stuff that like, do you know what I mean? Like, it doesn't matter to me. Like I wanna to give it to x (unintelligible utterance) simple and I want you to explain it to me and then we'll work through whatever we have to do. And even then they just give you information that like really means nothing to you. |

|

| 3.3. Mothers saw disconnects between their views/values and the SLP's views/values. | Mother 109: They don't listen to you. That drives me up the wall. Because like I'm the one that spend times with my kids. I know what he struggles with. And he said, the speech person there, said well we think he's doing great, dah dah dah dah. He doesn't have these problems anymore. And I was like, hey wait, let's back up here a little, because yeah he is doing lots better, but he can't say this and he can't say this and he can't say this. And like we did this capital state test form and he couldn't pronounce any of this stuff. And I'm like well maybe it's just because he doesn't have to pronounce them all the time. And I was like well maybe a lot of people don't have to pronounce them all the time and obviously he can't. And so obviously there's still problems and they kinda just shrugged it off. So, that right there to me is an issue because I'm not making this, do you know what I mean. Like he can't pronounce it, he just can't and so yeah…. And then the other ones that would always be like hey you know, let's (let's) um, either send him into a specialist or let's have his hearing checked, that was always been their like, I don't know, main thing. They're always like it might be his hearing, and we're like it's been checked a hundred times…. They're figure well if he would learn to read or if we could help him learn to read or learn to help with this and this and this, then the language thing would probably go away to a point. Which so, it wasn't seems like it was ever that huge to anyone else but us. So, but then they never saw the emotional problems either, the frustration out of him…. And then I just they're just so I don't know they're sometimes their expectations are like way, way high. Like I know what my son is capable of and I know and I always want him to be more. Like x him to reach for his goals. But come on, there's some things that they want that is just not, it's not gonna happen. |

Mother 106: We saw the progress. We kind of felt like she needed to go a little bit longer but they said she passed everything and was doing well and just to work on the worksheets at home but it's not the same…. She doesn't go to speech anymore. They stopped in the fall, which I think she needs to continue. “Cause people still say ‘What did you say?’” (106) |

|

Note. SLP = speech-language pathologist; IEP = Individualized Education Program.

Theme 4: Mothers Appeared Satisfied With the SLP Intervention Their Child Had Been Receiving

Despite the concerns expressed by mothers regarding the disclosure of their child's language disorder, mothers also reported being satisfied and appreciative of the interventions their children received. Mothers felt like their child's communication improved as a result of intervention.

We feel that he's able to get all this help from so many people. So we've really, really appreciated all the different people that have been able to help and all the resources that have come from it so that he can become that better person and show other people exactly the child we know he is. So it's nice to have that, that help. (101)

It was the end of preschool, just when she was ready to graduate, getting ready for kindergarten. Her teacher said “Let's get her in speech before she starts kindergarten so she'll do better”. And so we did a little bit of summer work with her and it really helped. (106)

Now they're like no we just have to make sure and that you're not struggling with something. I thought it was very thorough as far as what they covered and that he understood but maybe couldn't verbally respond as well as other kids. And they seemed to have done that always from you know when he was very you know initially tested…. I think he's had really good experiences with all of his teachers. (111)

I'm so grateful for those girls over there, they've done a great job with her, she's come miles and miles, with just, you know, the one-on-one help. (112)

Member Checking

To verify our interpretation of the results, we completed member checking after the data analysis once themes from the interviews had been identified. Member checking is one method for validating the interpretation of data from qualitative studies and is among the recognized standards of good practice in qualitative research (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; O'Brien et al., 2014). We used Synthesized Member Checking (Birt et al., 2016), a method where participants are provided with an opportunity to change or comment on themes that had been synthesized for review. We mailed a three-page summary of the results to each participant (see Supplemental Material S2) and asked the mothers to comment on the interpretation of the interviews. Mothers were provided a stamped envelope to return their comments to The University of Utah. 1 Five of the 12 mothers returned the member checking document (41.6%), a level of participation similar to the study of Birt et al. (2016; 44%) and higher than the studies of Shiyanbola et al. (2018; 10%) or Francis et al. (2018; 13.6%). Participants who completed member checking did so anonymously. Two of the documents were returned without parent comment. Overall, the other three parents agreed with the statements but noted anonymized subthemes or quotes that did not represent their experience. For example, although parents reported difficulties understanding the jargon used by SLPs, one parent reported on the member checking document, “This didn't apply to me, probably due to my background.” Another parent wrote, “I did not experience this,” next to a quote from a parent who wondered if they could believe the diagnosis provided by the SLP. The majority of subthemes and quotes went unchallenged, and therefore, our interpretations were not altered after member checking.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to generate a theory grounded in data that explained mothers' understanding of language disorder and the terms used to describe it while also exploring the role of SLPs in this process. All the mothers in this study knew that their child had communication problems, as evidenced by their seeking out treatment from an SLP. However, our findings indicated that most of the mothers had not received a formal diagnosis and did not understand the nature of their child's communication disorder. The results of our constant comparative analyses of the interviews have led us to theorize that the lack of formal clinical information provided to mothers about their child's language disorder causes mothers psychological harm that appears to be long lasting. We hypothesize that the lack of a specific and shared term for language disorder and the limited discussions with mothers describing potential etiologies of language disorder contributed specifically to mothers' negative emotions such as confusion, frustration, and guilt, beyond what would be expected if they had received this information. Furthermore, we theorize that the difficulties of effectively relaying information about language disorders to families result in negative perceptions of speech-language pathology.

Diagnostic Terminology

A key finding from this study is that mothers were provided numerous terms describing their child's language disorder. However, few of these terms could be used to access meaningful information about the nature of their child's communication problems (e.g., learning problems; see Schuele & Hadley, 1999). Other terms were inaccurate (e.g., cognitive delay, ADHD). SLPs may not be providing families with clear clinical labels for children's language disorder for a number of reasons. However, we propose that there are key areas of cognitive dissonance SLPs face when they are assessing children that may discourage the use of diagnostic terms.

One potential barrier to SLPs is the common developmental progression from initial language delays to lasting language disorders. All the children discussed in this study began receiving their services between the ages of 2 and 4 years, and mothers reported that they sought services early as a result of their concerns about their child's late language emergence (LLE). LLE is a clinically neutral term used in the research literature to describe children who are not meeting age expectations at 2 years and are considered at elevated risk for later language disorders (Taylor et al., 2013; Zubrick et al., 2007). Longitudinal research examining language development in children with LLE has found that, as a group, children with LLE at age 7 years have poorer morphosyntactic and syntactic abilities relative to those with typical language emergence but comparable semantic abilities (Taylor et al., 2013). However, evidence also suggests that the majority of children who present initially with LLE do not go on to develop a later language disorder (Dollaghan, 2013). Resultantly, SLPs providing early intervention services may be hesitant to diagnose language disorders in preschoolers because they worry about the negative consequences of providing provisional but potentially inaccurate diagnoses of children. This caution may be warranted in young preschool children. However, by ages 4–5 years, symptoms of language disorder have been shown to be fairly stable, warranting the provision of a diagnosis in older children (Tager-Flusberg & Cooper, 1999).

There may also be systemic barriers within the U.S. education system that hinder the adoption of any diagnostic label for children receiving speech-language pathology services in public schools. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004) mandates that children receive services for disabilities that have an adverse educational impact, including speech or language impairments. In this context, children receive school services based on the category “speech or language impairments” that require speech-language pathology services, which is independent of any clinical diagnosis. Consequently, SLPs' primary focus may be to audit children for potential service eligibility with less concern for the provision of a meaningful diagnostic label to families. However, this creates a disconnect between the expectations of families and the SLPs working with them. Families may have expectations of school SLPs similar to those they have for medical models of service provision, such that most assessments with a pathologist or other health care professional yield some type of diagnosis, even if it is a provisional diagnosis. When a diagnosis does not occur over the course of the school assessment process, mothers may either misinterpret eligibility information provided by SLPs as their child's diagnosis or interpret the absence of a formal diagnosis as an evasion by the SLP.

Emotional Distress

Our findings indicated that many mothers continued to be distressed about their child's language disorder for years following the outset of their child's language intervention. This continued emotional distress was an unexpected and previously undocumented finding. We believe that the type of emotional distress expressed by the mothers in this study sample falls under the general description of chronic sorrow. “Chronic sorrow” is a term used to describe the pervasive, recurrent sadness experienced by parents of children with a chronic illness or disability that has been classified as permanent, periodic, and progressive (Eakes et al., 1998; Olshansky, 1962). Although chronic sorrow of parents of children with disabilities has been widely documented across disability literature (see Coughlin & Sethares, 2017, for a review), these studies included families of children with potentially life-threatening illnesses (e.g., congenital heart disease, sickle cell disease, cancer) or demonstrable life-altering disabilities (e.g., cerebral palsy, neural tube defects, Type 1 diabetes). Comparatively, language disorder may be considered benign, and correspondingly, it could be argued that its diagnosis does not necessitate the same gravitas as other childhood disabilities. On the other hand, it could be argued that the relatively more benign but still serious academic, social, and vocational consequences associated with language disorders include the risk of these issues never being properly confronted and addressed. Although the assessment process occurred a minimum of 2 years before our interviews took place, three of the caregivers “teared up” during the interview process when talking about the grief that they had experienced when discovering that their child's language was not typically developing. SLPs may not be prepared for the magnitude of grief experienced by caregivers of children with language disorders (Luterman, 2016). While SLPs work with many populations confronting severe communication deficits, they may be unaware of the sensitivity needed when addressing those with disorders that have typically been considered less severe.

Coughlin and Sethares (2017) identified factors that affected parents' chronic sorrow, including their child's inability to reach expected developmental milestones such as entering school, transitioning into adolescence, and graduating from high school. Mothers in this study expressed similar concerns to those discussed by Coughlin and Sethares about their own children's future opportunities and well-being. A common attribute across parents of children with disabilities is that families encounter periodic crises rather than a time-bound adjustment to their children's disability. These shared experiences across groups of parents with disabilities and language disorders suggest that families of these children have more in common than not. The severity of the negative feelings shared by mothers in this study reveals an overlooked consequence of children's language disorders. Future research should consider chronic sorrow in parents of children with a language disorder and examine ways to ameliorate the stress experienced in these families over time.

Maternal Perspectives on Speech-Language Services

The mistrust of speech-language professionals expressed by mothers in the interviews originated from issues encountered over multiple years of their child's service provisions. Mothers expressed confusion over the lack of a clear language-related diagnostic term and lack of agreement across different SLPs about their child's disorder. Generally, mothers did not understand the information provided by their SLP, reporting particular difficulties following discussions of their child's language abilities. When parents fail to understand the information they receive, they lack a common ground from which to communicate their concerns or desires for their children. It is also difficult, if not essentially impossible, to effectively advocate for your child if you cannot explain their problem to family, friends, teachers, and employers. A terminological shift toward developmental language disorder may eventually alleviate some of the negative experiences associated with being a parent of a child with an idiopathic language disorder. The term “developmental language disorder” was endorsed by the CATALISE Consortium (Bishop et al., 2016) after a Delphi technique was used to achieve consensus on a label for language disorder with unknown etiology. The hope of those contributing to the CATALISE Consortium (Bishop et al., 2017) was that those working in the field of children's language problems would use developmental language disorder across professional settings. The CATALISE Consortium recognized that the lack of a consistent term for idiopathic language disorder represents a major liability problem for the field of speech-language pathology. If the developmental language disorder label is adopted by school-based SLPs, it may go far to alleviate the negative experiences of the families of children who have not received a diagnostic label.

However, although the use of a consistent label within the profession of SLPs may assist in improving the experiences of families, it may be difficult to implement across settings. A recent literature review highlighted divergent perspectives between educators and SLPs that may prevent the use of “any” label to categorize children's language disorders in school-based services. Gallagher et al. (2019) reviewed 81 papers from speech-language pathology and education to ascertain the extent that SLPs and teachers share an understanding of language disorders. The literature demonstrated key differences in perspectives surrounding diagnostic labeling between the two fields. Most of the education literature reported that diagnostic labels should be avoided because of the potential harms associated with “deterministic thinking,” providing warnings that teachers would have lower expectations of children who had received a label. Furthermore, language disorders were viewed as the result of environmental factors that could be minimized in the classroom to increase language performance. In contrast, the speech-language pathology literature framed language disorders as an intrinsic neurodevelopmental condition, proposing that SLPs must understand the disorder before effective intervention can take place (Gallagher et al., 2019). For SLPs working in school settings, these conflicting value systems may result in clinicians not providing families with a diagnostic label of language disorder, regardless of terminology agreed upon by those in the speech-language pathology profession. If school-based practitioners feel it is not within their purview to provide families with a diagnostic label, it will be difficult for families to grasp what is taking place with their children. Communication barriers between SLPs and families are then likely to continue and compound.