Abstract

Chemical synapses between taste cells were first proposed based on electron microscopy of fish taste buds. Subsequently, researchers found considerable evidence for electrical coupling in fish, amphibian, and possibly mammalian taste buds. The development of lingual slice and isolated cell preparations allowed detailed investigations of cell-cell interactions, both chemical and electrical, in taste buds. The identification of serotonin and ATP as taste neurotransmitters focused attention onto chemical synaptic interactions between taste cells. Research on electrical coupling faded. Findings from Ca2+ imaging, electrophysiology, and molecular biology indicate that several neurotransmitters, including ATP, serotonin, GABA, acetylcholine, and norepinephrine, are secreted by taste cells and exert paracrine interactions in taste buds. Most work has been done on interactions between Type II and Type III taste cells. This brief review follows the trail of studies on cell-cell interactions in taste buds, from the initial ultrastructural observations to the most recent optogenetic manipulations.

Keywords: neurotransmitters, dye-coupling, gap junctions, paracrine, autocrine, ATP, serotonin, GABA

This tale begins with a pet swordtail fish, limply swimming upside down in an aquarium in Prof. Klaus Reutter’s laboratory. Recognizing that the fish was near its end, Reutter anesthetized, fixed, and embedded the swordtail for histological inspection. Captivated by the structural beauty of the fish’s taste buds, Reutter went on to study the ultrastructure of these gustatory end organs. His ultrastructural analyses on the bullhead catfish (Amiurus nebulosus [Lesueur]) [1,2] were the first to identify putative chemical synapses between adjacent cells in taste buds. He speculated that in catfish, excitation of one taste cell is “intensified or is coordinated” with activity in adjacent cell(s) prior to transmitting signals to the CNS, articulating the first suggestion that there might be signal processing in the peripheral sense organs of taste.

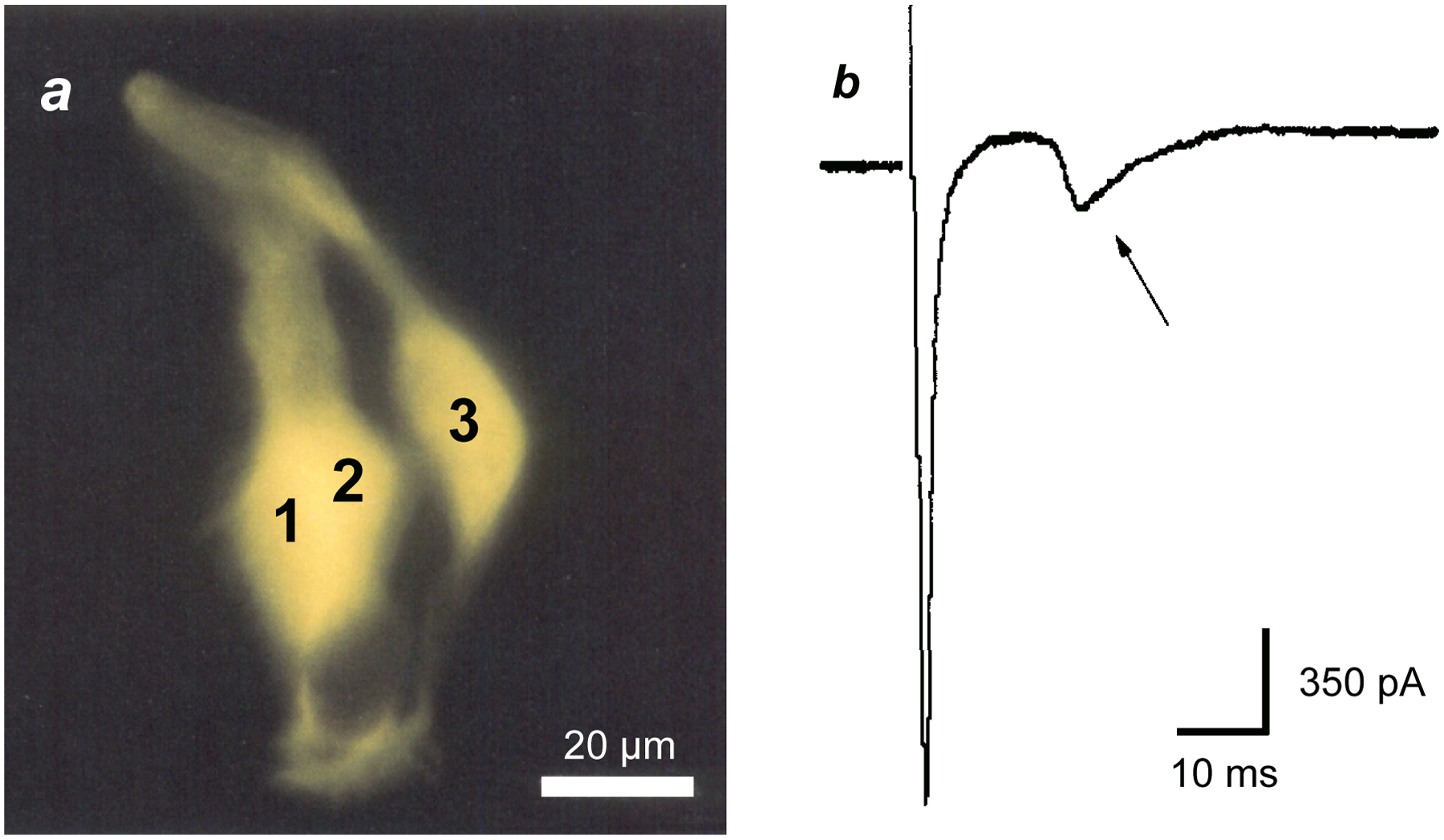

Cell-cell synaptic interactions and paracrine synaptic transmitters have since been identified using physiological techniques. Shortly after the ultrastructural identification of chemical synapses between taste bud cells, researchers also uncovered possible electrical coupling. Namely, by penetrating adjacent cells in the large taste buds of the amphibian, Necturus maculosus with sharp, dye-filled microelectrodes, West et al [3] and Yang et al [4] observed electrical- and dye-coupling, presumably via gap junctions between taste bud cells (Fig. 1a). Similarly, researchers reported dye-coupling between taste cells in catfish and frogs [5,6]. The concern that this electrical- and dye-coupling between taste cells might be an artifact from cell damage during microelectrode penetrations was dispelled by studies where two dyes of differing molecular dimensions (Lucifer Yellow, rhodamine dextran) were injected into single taste bud cells in Necturus. The larger molecule (rhodamine dextran) remained trapped in the one cell, while the smaller, Lucifer yellow, penetrated into adjacent cells presumably via gap junctions [4]. Subsequently, Bigiani et al [7–9] extensively studied coupling between Necturus taste bud cells with patch clamp recordings in a lingual slice preparation. Electrical coupling in these taste buds is quite widespread (~20% of taste cells are coupled, [4,7]) and coupling is strong (80–90% of signal is transmitted across the junctions [9]) (Fig. 1b). Coupling was strongly reduced by acid (sour) stimuli or octanol [8], agents known to block electrical synapses [10,11].

FIGURE 1. Dye- and electrical coupling between taste bud cells in the amphibian, Necturus maculosus.

a, three taste cells were dye-filled after injecting cell 1 with Lucifer yellow (cells 1, 2 are slightly superimposed). Modified from [4]. b, Whole-cell currents recorded from an electrically-coupled taste receptor cell in Necturus maculosus. Current from an action potential in the patched cell (initial inward transient current) was transmitted to and excited a neighboring taste cell, seen as the second, smaller and slower transient inward current (arrow). The patched cell was excited by momentarily stepping the membrane potential from a holding potential of −80 mV to −20 mV. Modified from [9].

Soon after these findings on cell coupling in fish and amphibian taste buds were published, Yoshii [12] briefly reported data on cell-cell communication via gap junctions in mouse taste buds. This was consistent with earlier findings using freeze fracture electron microscopy that had revealed structures resembling gap junctions in rat taste buds [13]. These two studies provided evidence, albeit limited, for electrical coupling in mammalian taste buds.

Since Yoshii’s publication, there have been many descriptions of gap junction channel protein (connexin) expression in mouse taste buds. Curiously, however, these reports have focused exclusively on the role that these channels might play in secreting the neurotransmitter ATP from taste bud cells. The existence of electrical coupling between taste bud cells was overshadowed and apparently forgotten. To sum up the expression data, RT-PCR and immunostaining reveal a number of connexins, mainly in Types I and II, but not Type III taste cells, in fungiform, valate, and foliate taste buds [14–16]. Cx 43 and Cx 30 are often reported as being present, but as Huang et al [14] point out, these connexins are strongly expressed in surrounding, non-taste epithelium; their presence in preparations of isolated taste cells or dissected taste tissue might readily be explained by contamination.

Perhaps more convincingly, Sukumaran et al [17] published single cell transcriptome data from mouse valate taste buds that revealed a number of connexins (Cx26,30,31,31.1,40,43) expressed in Type II cells. Further, RNAseq analyses on pools of identified Type I, II, and III taste bud cells from mouse fungiform taste buds reported strong expression of Cx47 in Type II cells (unpublished data, Dvoryanchikov and Chaudhari). Interestingly, Cx43 or Cx30, were not detected, a finding that differs from Sukumaran et al (ibid.), but that is consistent with immunostaining and RT-PCR data [14].

Lastly, Romanov et al [18] provided electrophysiological evidence for the expression of (unspecified) gap junction connexin hemichannels in Type II mouse taste buds. That study was conducted on isolated taste bud cells and thus does not provide information, either for or against, about gap junctions in situ.

In sum, there is abundant, albeit fragmentary evidence, including ultrastructural, molecular, and functional, for dye- and electrical coupling between taste bud cells. The specific connexins that might comprise putative gap junctions in taste buds are not known with confidence. Evidence for cell-cell coupling in taste buds is most compelling in fish and amphibia. Electrical coupling in mammalian taste buds has not yet been studied at the same level of detail. Electrical- and dye-coupling between mammalian taste bud cells clearly needs to be measured with the same care and attention as has been done in fish and amphibia1.

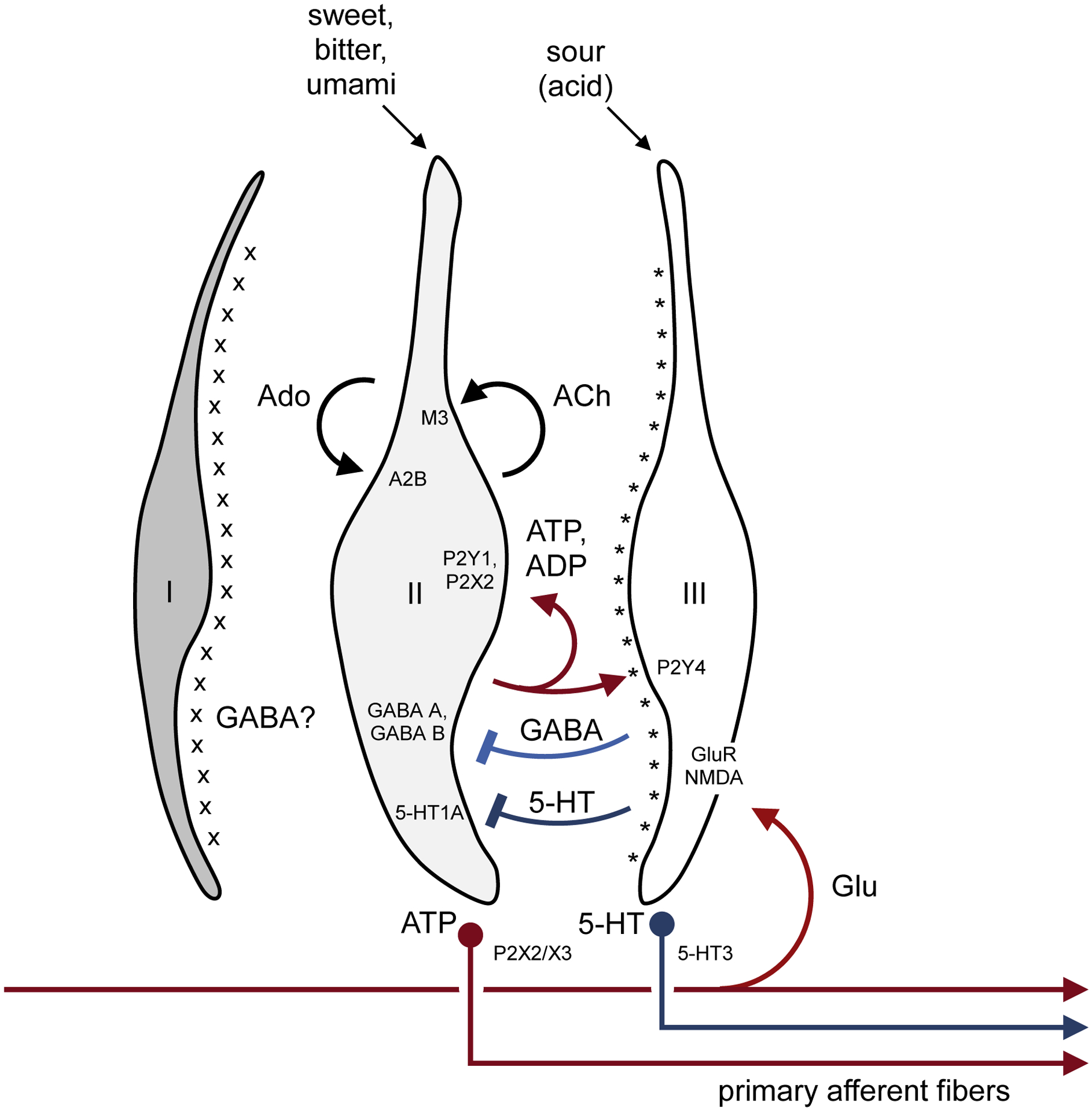

In the years following the discovery of gap junction coupling between taste cells, the identification of ATP and serotonin as taste transmitters [23,24] and reports of paracrine synaptic interactions in taste buds [25–37] have dominated the field and drawn attention away from electrical coupling. Detailed experimentation has led to the realization that taste cells communicate among themselves within the taste bud via paracrine neurotransmitters while at the same time (or preceding) transmitting signals to the CNS via gustatory primary afferent fibers. The principal taste bud transmitter, ATP, not only excites primary afferent terminals but also acts as an autocrine (positive feedback) transmitter, possibly to boost taste-evoked transmitter release [37]. Type II taste cells release ATP [14,15]. Degradation of ATP to adenosine during taste transmitter secretion produces another excitatory transmitter, adenosine, that also stimulates Type II taste cells [29], perhaps in an autocrine manner (self-feedback) or by acting on neighboring cells (paracrine excitation). Acetylcholine (ACh), GABA, and norepinephrine (NE) are additional transmitters released during taste stimulation [30,34,38]. ATP, adenosine, and ACh are released by Type II cells and appear to be excitatory transmitters, while GABA and serotonin, secreted by Type III taste bud cells, are inhibitory to Type II cells [33,35,36,39]. Lastly, glutamate, released from primary sensory afferent collaterals (“axon reflex”) [40] or from postulated efferent fibers [41], excites Type III cells. By exciting Type III cells and eliciting 5-HT release, glutamatergic feedback ultimately inhibits transmitter (ATP) secretion from Type II cells [40]. Figure 2 summarizes these interactions.

FIGURE 2. Schematic diagram summarizing feedforward and feedback signaling in mammalian taste buds.

The diagram shows the three principal types of taste bud cells. Type I cells express NTPDase2 on their surface (x). NTPDase2 is an ecto-ATPase that degrades ATP released during taste excitation. Type II cells express G protein–coupled taste receptors for sweet, bitter, or umami taste compounds. Taste stimulation evokes ATP secretion from Type II cells. By activating P2Y and P2X purinergic receptors, ATP excites (a) gustatory primary afferent fibers (shown at bottom), (b) neighboring Type III taste bud cells, and (c) (via autocrine feedback) Type II cells, as shown above in red. ATP released during taste stimulation is degraded to ADP and adenosine (Ado), both of which along with ATP serve as autocrine positive feedback signals. Type II cells also release acetylcholine (ACh) as autocrine feedback. Type III cells make synaptic contacts with nerve fibers and secrete serotonin (5-HT) (and norepinephrine, not shown). Type III cells also release GABA when stimulated by acids (sour tastants). GABA and 5-HT from Type III cells inhibit Type II cells, shown above in blue. Type III cells also express ecto-nucleotidases (*), NT5E and prostatic acid phosphatase, that convert AMP to adenosine. Lastly, glutamate, possibly released from axon collaterals of primary afferent fibers or efferent innervation [40,41], activates Type III cells. Not shown are gustatory primary afferent fibers with branches that innervate both Type II and Type III taste cells [46]. Receptors for ATP, ADP, adenosine, acetylcholine, GABA, glutamate, and 5-HT are identified in the target sites. For clarity, peptidergic interactions have been omitted. From ref [42].

Notably, for clarity, Figure 2 leaves out intercellular communication via electrical synapses. It also does not include putative cell-cell transmission in taste buds via peptide neurotransmitters [26,43–45] or collateral branches of primary afferent fibers that innervate both Type II and Type III taste cells [46].

Precisely how paracrine transmitters and electrical synapses shape the output from taste buds during gustatory stimulation remains to be elucidated. Some years ago, Ewald et al [47] took advantage of the large taste cells in the amphibian, Necturus maculosus to explore cell-cell transmission in taste buds.

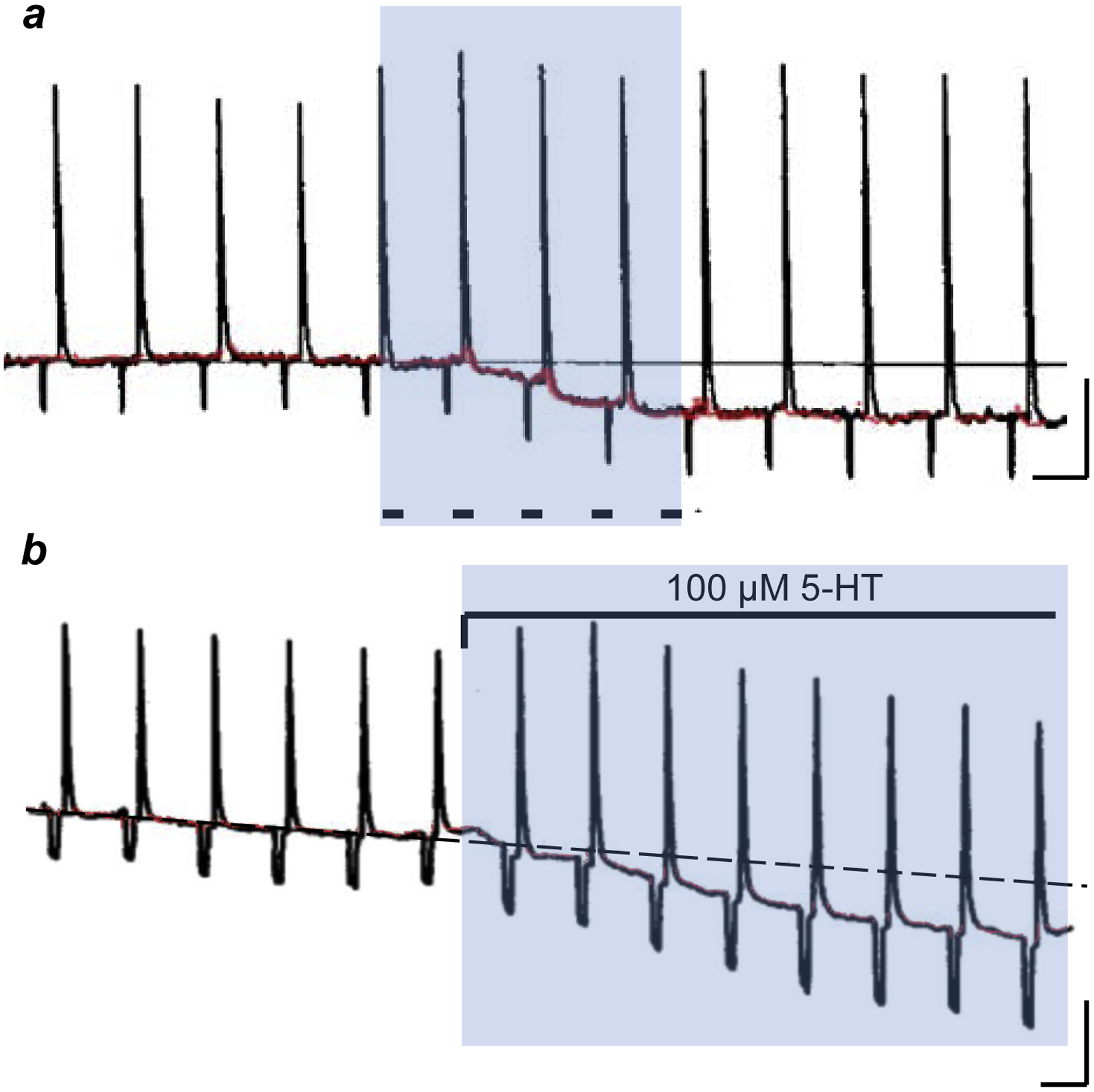

They concurrently impaled and recorded activity in two adjacent taste bud cells—a receptor cell and a serotonergic basal taste cell—imaged in a lingual slice preparation2. In 16% of the recordings where two adjacent taste cells were impaled with microelectrodes, depolarizing the receptor cell evoked small responses in the other (serotonergic) cell, suggestive of excitatory synaptic coupling3. Importantly, the converse experiment—stimulating the serotonergic basal cell—elicited a slow, prolonged hyperpolarization of the receptor cell (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the receptor cell hyperpolarization was mimicked by bath-applying serotonin (Fig. 3b). These data foreshadowed later experiments on mammalian taste buds that indicate that serotonergic taste cells (Type III) exert feedback inhibition onto neighboring Type II receptor cells (summarized in Fig. 2; also see below). Intriguingly, Ewald et al [47] stated that their study “suggests that there is extensive synaptic convergence from receptor cells onto each (serotonergic) basal cell”, a conclusion that was independently reached for mammalian circumvallate taste buds some 13 years later [50].

FIGURE 3. Synaptic transmission between taste bud cells in lingual slices from Necturus maculosus.

a, Intracellular recording from a taste bud receptor cell. Repeated focal application of a salt taste stimulus (KCl) to the taste pore elicits repeated large receptor potentials. [Taste stimuli were alternated with brief hyperpolarizing constant current pulses (not shown) to monitor the input resistance, resulting in the small ~5 mV hyperpolarizations shown in the trace]. During the shaded interval, an adjacent serotonergic basal cell was excited by injecting depolarizing current through a second intracellular microelectrode (5 pulses, 1 sec duration, dashes). The resting potential of the taste receptor cell (red) shows the slow hyperpolarization evoked by basal cell stimulation. N.B. the membrane resistance also increases (i.e., heightened responses to brief hyperpolarizing current pulses and KCl-evoked receptor potentials). b, A different taste bud receptor cell, similar presentation as in a with apical focal KCl stimulation and brief hyperpolarizing constant current pulses. Here, bath-applying 100 μM serotonin (5-HT, shaded region) mimics the hyperpolarization produced by stimulating an adjacent basal cell in a. Calib, 10 mV, 10 sec. Modified from [47].

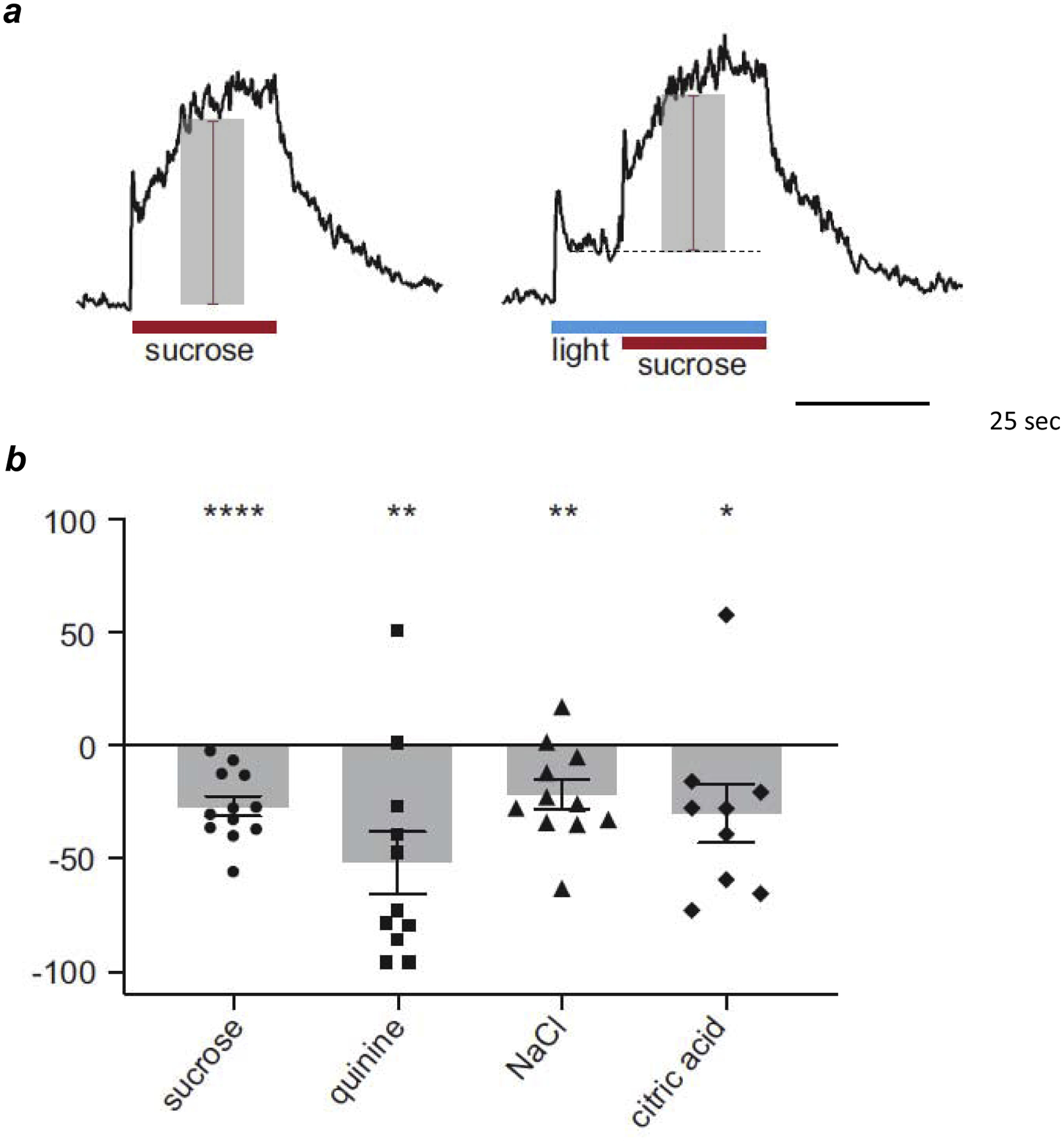

As noted above, during taste activation, Type III taste bud cells secrete serotonin and GABA and these transmitters inhibit neighboring Type II taste receptor cells (Fig. 2). Recently, Vandenbeuch et al [51] designed experiments to stimulate Type III cells selectively using optogenetic techniques and determine how activating these cells modulates gustatory responses from taste buds. They genetically engineered mice to express the light-sensitive ion channel, channelrhodopsin (ChR2), in Type III cells, allowing the researchers to activate those cells with brief pulses of blue light. Specifically, Vandenbeuch et al [51] excited Type III cells during taste stimulation with sweet, bitter, salty, or sour tastants applied to the tongue. They monitored tastant-evoked signals by recording electrical activity in the chorda tympani nerve. Findings summarized above would predict that selectively stimulating Type III cells would inhibit taste cells and reduce signal output during gustatory stimulation. Indeed, this is precisely what they found. Blue light pulses projected onto the tongue during sweet, bitter, salty, or sour (acid) taste stimulation reduced nerve activity in the chorda tympani compared to when these gustatory stimuli were applied in the absence of light pulses (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4. Effect of optogenetically stimulating Type III taste bud cells.

a, Representative integrated chorda tympani responses to 500 mM sucrose applied to the tongue before (left) and during optogenetic stimulation (right, “light”) in a mouse that expressed channelrhodopsin in Type III taste bud cells. Amplitudes of taste-evoked responses are shown by shaded bars, red lines. Baseline during lightevoked response without taste stimulation (not shown) shown by dashed line. b, percent reduction of taste-evoked responses during Type III cell activation (sucrose 500 mM; quinine 10 mM; NaCl 100 mM; citric acid 10 mM). Each symbol represents a different animal for each tastant. Bars show averages ± s.e.m. All responses normalized to responses to NH4Cl 100 mM. Statistical significance based on single sample t-tests: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Modified from [51].

The ability of selective (optogenetic) activation of Type III cells to reduce the sweet and bitter taste-evoked signals [51] by could be explained by the interactions summarized in Figure 2 and by the fact that sweet and bitter tastes primarily activate Type II cells. Interpreting how stimulating Type III cells reduced acid- and salt-evoked signals is a bit more problematic. Acids (sour taste) directly activate Type III cells; the cells underlying salt taste are still being identified. Perhaps simultaneous activation of Type III cells by optogenetic and taste stimulation is not additive, as the authors explain [51]. Alternatively (or additionally), GABA and serotonin secreted by Type III cells may exert an autocrine (self) inhibition. Further, the ability of acid stimuli block gap junctions [8] may contribute to the observed inhibition4.

Looking forward, one possible way to resolve the question of cell-cell interactions and signal processing in taste buds during gustatory stimulation will be to combine finer-resolution electrophysiological recordings (e.g., single fiber activity in the chorda tympani nerve) or functional imaging of sensory ganglion neurons with optogenetic stimulation of Type III cells, and to use pharmacological agents to block GABAergic and serotonergic signaling. Given the paucity of information about the molecular composition of gap junctions, it is not yet possible to engineer knockout mice that would lack the appropriate connexons or to propose specific antagonists to reduce electrical coupling between taste cells to test a role of gap junctions. In any case, a formidable challenge to any pharmacological manipulations of cell-cell interactions, whether chemical or electrical, in taste buds is the presence of a robust barrier protecting taste bud cells from many topically-applied or injected agents [54,55].

Summary and conclusions:

There is a rich variety of synaptic interactions among cells within the peripheral end organs of taste. These include electrical and chemical contacts, paracrine and autocrine synapses, feed forward and feedback influences, and excitatory and inhibitory transmission. Figure 5 summarizes this cell-cell communication in taste buds. How these interactions shape the signals generated in taste buds during gustatory stimulation remains to be explicated.

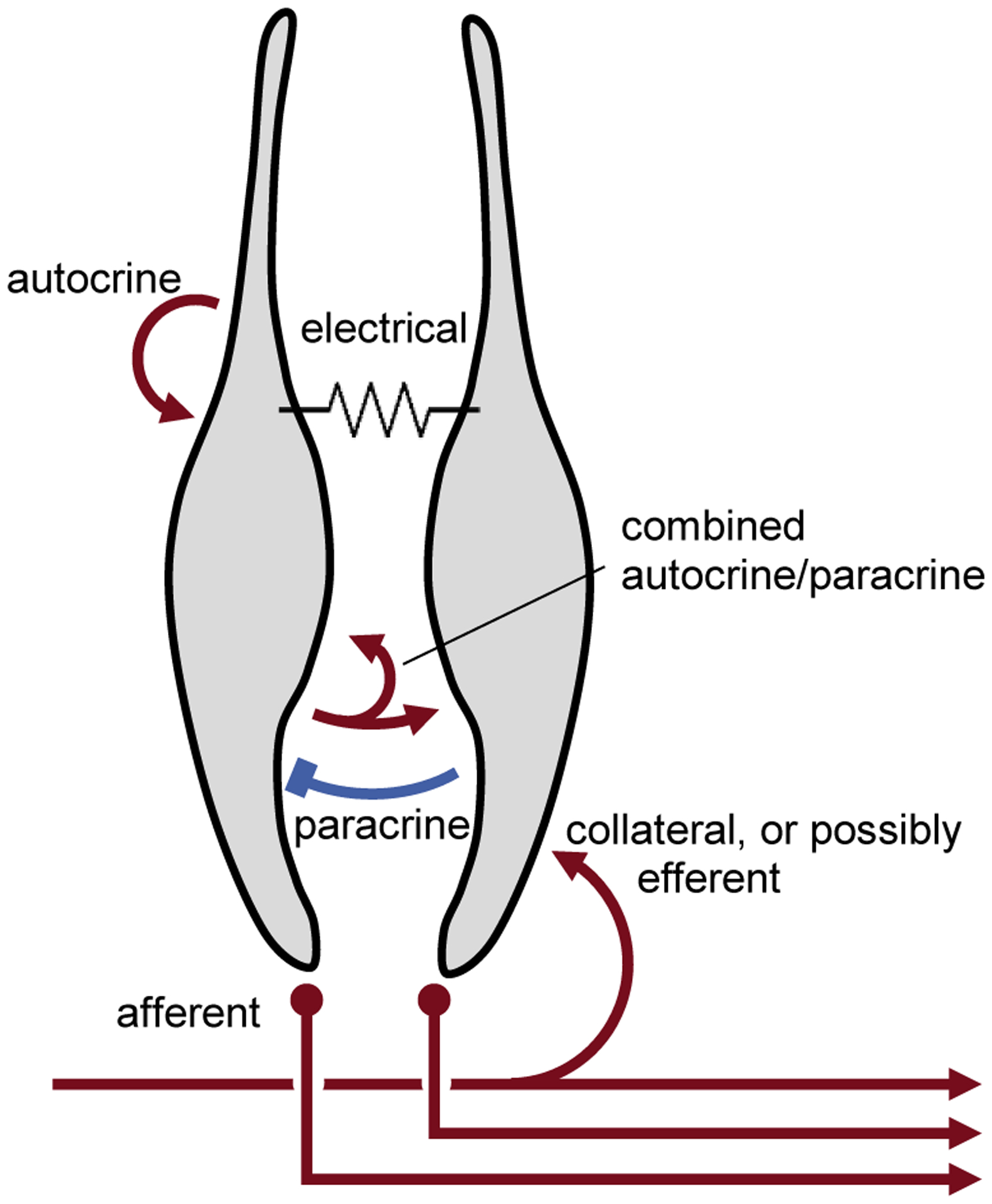

FIGURE 5. Summary of cell-cell interactions in taste buds.

Red symbols indicate excitatory interactions; blue, inhibitory. Specific taste bud cell type(s) and the transmitters involved have not been identified for clarity and simplification. Details in text.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to acknowledge and thank S A Simon (Duke) and N Chaudhari for their helpful comments. I dedicate this article to Douglas A Ewald, my friend and former collaborator at Colorado State University. Doug helped pioneer the lingual slice preparation for studying taste buds ex vivo and was the first to record cell-cell interactions between taste cells, described in the above review. Doug passed away in June 2020. This work has been supported over the recent years by NIH grants R01DC018733, R01DC017303, R01DC006308, R01DC014420, and R01DC007630.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

I declare I have no conflicts.

Parenthetically, apart from the work of Akisaka et al [13], careful and detailed ultrastructural analyses of rat and mouse circumvallate taste buds, including 3D reconstructions from high voltage electron microscopy and scanning electron microscopy of serial blockface sections [19–22] have failed to reveal conventional gap junctions between taste cells. This is not unexpected, however, given that none of these latter studies used freeze-fracture methodologies that would reveal gap junctions [13]. Moreover, large plaques that characterize gap junctions in other tissues would not be needed to explain the extent of dye- and electrical coupling between taste bud cells [9].

Ewald et al [47] termed the serotonergic cell a “basal” cell, not to be confused, with undifferentiated progenitor taste cells. The serotonergic “basal” taste cells in Necturus taste buds may be analogous to Type III taste cells in mammalian taste buds [48,49], though homology has not been established.

Importantly, hyperpolarizing receptor cells failed to show basal cell responses, consistent with chemical, not electrical synaptic connections between receptor and “basal” cells.

Interestingly, the behavioral effects of optogenetically stimulating Type III cells have yielded conflicting data. Zocchi et al [52] reported that optogenetically activating Type III taste bud cells with blue light pulses in unrestrained, awake mice stimulated water drinking, leading them to conclude that Type III cells are involved in thirst behavior. However, Wilson et al [53] reported the opposite. In their hands, optogenetic activation of Type III cells elicited aversive taste behavior. These differences remain unresolved.

References

- 1.Reutter K 1971[taste buds of the dwarf catfish, amiurus nebulosus (lesueur). Electron microscopic and histochemical studies]. Verh Anat Ges;65:511–2. Epub 1971/01/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reutter K 1978. Taste organ in the bullhead (teleostei). Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol;55(1):3–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West CH, Bernard RA. 1978Intracellular characteristics and responses of taste bud and lingual cells of the mudpuppy. J Gen Physiol;72(3):305–26. Epub 1978/09/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J, Roper SD. 1987. Dye-coupling in taste buds in the mudpuppy, necturus maculosus. J Neurosci;7(11):3561–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teeter JH. 1985. Dye-coupling between cells in catfish taste buds. Chem Senses;11(2):266. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sata O, Okada Y, Miyamoto T, Sato T. 1992Dye-coupling among frog (rana catesbeiana) taste disk cells. Comp Biochem Physiol Comp Physiol;103(1):99–103. Epub 1992/09/01. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigiani A, Roper SD. 1993. Identification of electrophysiologically distinct cell subpopulations in necturus taste buds. J Gen Physiol;102(1):143–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bigiani A, Roper SD. 1994. Reduction of electrical coupling between necturus taste receptor cells, a possible role in acid taste. Neurosci Lett;176(2):212–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigiani A, Roper SD. 1995. Estimation of the junctional resistance between electrically coupled receptor cells in necturus taste buds. J Gen Physiol;106(4):705–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spray DC, Harris AL, Bennett MV. 1981. Gap junctional conductance is a simple and sensitive function of intracellular pH. Science;211(4483):712–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston MF, Simon SA, Ramon F. 1980Interaction of anaesthetics with electrical synapses. Nature;286(5772):498–500. Epub 1980/07/31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshii K 2005Gap junctions among taste bud cells in mouse fungiform papillae. Chem Senses;30Suppl 1:i35–6. Epub 2005/03/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akisaka T, Oda M. 1978. Taste buds in the vallate papillae of the rat studied with freeze-fracture preparation. Arch Histol Cytol;41(1):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14*.Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2007The role of pannexin 1 hemichannels in atp release and cell-cell communication in mouse taste buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA;104(15):6436–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper and the next (Romanov et al, 2007), published at about the same time, established that the principal neurotransmitter in taste buds, ATP, is secreted by Type II taste cells. Moreover, Type II cells secreted ATP in an unorthodox manner. Unlike conventional synaptic vesicular release, ATP is secreted through large-pore plasma membrane channels, then believed to be pannexin-1 (Huang et al) or connexon hemichannels (Romanov et al). ATP was later shown to be secreted via CaLHM1/3 channels.

- 15*.Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Bystrova MF, Jiang P, Margolskee RF, Kolesnikov SS. 2007Afferent neurotransmission mediated by hemichannels in mammalian taste cells. EMBO J;26(3):657–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (See above commentary)

- 16.Vandenbeuch A, Anderson CB, Kinnamon SC. 2015. Mice lacking pannexin 1 release atp and respond normally to all taste qualities. Chem Senses;40(7):461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukumaran SK, Lewandowski BC, Qin Y, Kotha R, Bachmanov AA, Margolskee RF. 2017Whole transcriptome profiling of taste bud cells. Sci Rep;7(1):7595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romanov RA, Kabanova NV, Malkin SL, Kolesnikov SS. 2009Nonselective voltage-gated ionic channels in type ii taste cells. Biochemistry (Moscow) Supplement Series A: Membrane and Cell Biology;3(1):71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pumplin DW, Yu C, Smith DV. 1997Light and dark cells of rat vallate taste buds are morphologically distinct cell types. J Comp Neurol;378(3):389–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Yang RB, Dzowo YK, Wilson CE, Russell RL, Kidd GJ, Salcedo E, Lasher RS, Kinnamon JC, Finger TE. 2020. Three-dimensional reconstructions of mouse circumvallate taste buds using serial blockface scanning electron microscopy: I. Cell types and the apical region of the taste bud. J Comp Neurol;528(5):756–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Serial blockface scanning electron microscopy is the foundation for much of brain connectomics. In an important advance for understanding the “taste bud connectome”, that is, cell-cell interactions in taste buds, Yang et al (2020) have begun applying this powerful technique to a study of these end organs of taste. Their main finding in this first paper of what appears will be a series, is a detailed description of the four taste bud cell types and of taste cell synapses.

- 21.Kinnamon JC, Sherman TA, Roper SD. 1988Ultrastructure of mouse vallate taste buds: III. Patterns of synaptic connectivity. J Comp Neurol;270(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kinnamon JC, Taylor BJ, Delay RJ, Roper SD. 1985Ultrastructure of mouse vallate taste buds. I. Taste cells and their associated synapses. J Comp Neurol;235(1):48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Lu KS, Pereira E, Plonsky I, Baur JE, Wu D, Roper SD. 2005Mouse taste buds use serotonin as a neurotransmitter. J Neurosci;25(4):843–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finger TE, Danilova V, Barrows J, Bartel DL, Vigers AJ, Stone L, Hellekant G, Kinnamon SC. 2005Atp signaling is crucial for communication from taste buds to gustatory nerves. Science;310(5753):1495–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herness MS, Chen Y. 2000. Serotonergic agonists inhibit calcium-activated potassium and voltage-dependent sodium currents in rat taste receptor cells. J Membr Biol;173(2):127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herness S, Zhao FL. 2009The neuropeptides cck and npy and the changing view of cell-to-cell communication in the taste bud. Physiol Behav;97(5):581–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herness S, Zhao FL, Kaya N, Lu SG, Shen T, Sun XD. 2002Adrenergic signalling between rat taste receptor cells. J Physiol;543(Pt 2):601–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaya N, Shen T, Lu SG, Zhao FL, Herness S. 2004. A paracrine signaling role for serotonin in rat taste buds: Expression and localization of serotonin receptor subtypes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol;286(4):R649–R58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dando R, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2012Adenosine enhances sweet taste through a2b receptors in the taste bud. J Neurosci;32(1):322–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dando R, Huang YA, Roper SD. 2010Acetylcholine, released from taste buds during gustatory stimulation, enhances taste responses. Chem Senses;35(7):A2–A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dando R, Roper SD. 2009. Cell-to-cell communication in intact taste buds through atp signalling from pannexin 1 gap junction hemichannels. J Physiol;587(24):5899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dando R, Roper SD. 2012. Acetylcholine is released from taste cells, enhancing taste signalling. J Physiol;590(13):3009–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang YA, Dando R, Roper SD. 2009Autocrine and paracrine roles for atp and serotonin in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci;29(44):13909–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang YA, Maruyama Y, Roper SD. 2008Norepinephrine is coreleased with serotonin in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci;28(49):13088–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang YA, Roper SD. 2009. Serotonin (5-ht) inhibits atp secretion in mouse taste buds. Chem Senses;34(7):A66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang YA, Roper SD. 2010. Gaba inhibition in mouse taste buds. Chem Senses;35(7):A78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang YA, Stone LM, Pereira E, Yang R, Kinnamon JC, Dvoryanchikov G, Chaudhari N, Finger TE, Kinnamon SC, Roper SD. 2011Knocking out p2x receptors reduces transmitter secretion in taste buds. J Neurosci;31(38):13654–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang YA, Pereira E, Roper SD. 2011. Acid stimulation (sour taste) elicits gaba and serotonin release from mouse taste cells. PLoS One;6(10):e25471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dvoryanchikov G, Huang YA, Barro-Soria R, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2011Gaba, its receptors, and gabaergic inhibition in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci;31(15):5782–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang YA, Grant J, Roper S. 2012Glutamate may be an efferent transmitter that elicits inhibition in mouse taste buds. PLoS One;7(1):e30662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vandenbeuch A, Tizzano M, Anderson CB, Stone LM, Goldberg D, Kinnamon SC. 2010. Evidence for a role of glutamate as an efferent transmitter in taste buds. BMC Neurosci;11(1):77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roper SD, Chaudhari N. Taste coding and feed-forward/feedback signaling in taste buds. In: Shepherd G, Grillner S, editors. Handbook of brain microcircuits, 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017. p. 277–83. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Herness MS. 1989Vasoactive intestinal peptide-like immunoreactivity in rodent taste cells. Neuroscience;33(2):411–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lu SG, Zhao FL, Herness S. 2003. Physiological phenotyping of cholecystokinin-responsive rat taste receptor cells. Neurosci Lett;351(3):157–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen T, Kaya N, Zhao FL, Lu SG, Cao Y, Herness S. 2005Co-expression patterns of the neuropeptides vasoactive intestinal peptide and cholecystokinin with the transduction molecules alpha-gustducin and t1r2 in rat taste receptor cells. Neuroscience;130(1):229–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang T, Ohman LC, Clements AV, Whiddon ZD, Krimm RF. 2020Variable branching characteristics of peripheral taste neurons indicates differential convergence. bioRxiv:2020.08.20.260059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ewald DA, Roper SD. 1994Bidirectional synaptic transmission in necturus taste buds. J Neurosci;14(6):3791–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delay RJ, Taylor R, Roper SD. 1993Merkel-like basal cells in necturus taste buds contain serotonin. J Comp Neurol;335(4):606–13. Epub 1993/09/22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim DJ, Roper SD. 1995. Localization of serotonin in taste buds: A comparative study in four vertebrates. J Comp Neurol;353(3):364–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50*.Tomchik SM, Berg S, Kim JW, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2007Breadth of tuning and taste coding in mammalian taste buds. J Neurosci;27(40):10840–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first paper to detail how cells in mammalian taste buds interact synaptically. Tomchik et al (2007) used high resolution confocal Ca2+ imaging of taste buds in lingual slices from mice that express fluorescent markers selectively in Type II or Type III cells. They showed that Type II cells respond mainly to individual taste qualities (e.g., either sweet or bitter), consistent with what was known about Type II cell expression of taste receptors. Importantly, Tomchik et al (2007) found that Type III cells in intact taste buds respond to multiple taste stimuli, in contrast to their limited sensitivity to sour (acid) taste stimulation in isolated cell preparations. The main conclusion from this report is that in taste buds, Type II taste cells synaptically converge onto (excite) Type III cells.

- 51*.Vandenbeuch A, Wilson CE, Kinnamon SC. 2020Optogenetic activation of type III taste cells modulates taste responses. Chem Senses;45(7):533–9. Epub 2020/06/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Vandenbeuch et al (2020) engineered mice to express channelrhodopsin in Type III taste cells. This allowed these researchers to activate Type III cells optogenetically during gustatory stimulation. The goal was to test whether exciting Type III cells affects taste responses when sweet, sour, salty, or bitter solutions were applied to the tongue. The main finding is that activating Type III taste cells while passing gustatory stimuli over the tongue reduced tasteevoked responses in the chorda tympani nerve. That finding is consistent with the notion that there are cell-cell interactions in the taste bud, and specifically that Type III taste cells inhibit other taste bud cells.

- 52.Zocchi D, Wennemuth G, Oka Y. 2017The cellular mechanism for water detection in the mammalian taste system. Nat Neurosci;20(7):927–33. Epub 2017/05/30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson CE, Vandenbeuch A, Kinnamon SC. 2019. Physiological and behavioral responses to optogenetic stimulation of PKD2l1+ type III taste cells. eNeuro;6(2)(2). Epub 2019/05/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michlig S, Damak S, Le Coutre J. 2007Claudin-based permeability barriers in taste buds. J Comp Neurol;502(6):1003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dando R, Pereira E, Kurian M, Barro-Soria R, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. 2015A permeability barrier surrounds taste buds in lingual epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol;308(1):C21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]