Abstract

Background

The United States is experiencing an opioid overdose crisis accounting for as many as 130 deaths per day. As a result, health care providers are increasingly aware that prescribed opioids can be misused and diverted. Prescription of pain medication, including opioids, can be influenced by how health care providers perceive the trustworthiness of their patients. These perceptions hinge on a multiplicity of characteristics that can include a patient’s race, ethnicity, gender, age, and presenting health condition or injury. The purpose of this study was to identify how trauma care providers evaluate and plan hospital discharge pain treatment for patients who survive serious injuries.

Methods

Using a semi-structured guide from November 2018 to January 2019, we interviewed 12 providers (physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants) who prescribe discharge pain treatment for injured patients at a trauma center in Philadelphia, PA. We used thematic analysis to interpret these data.

Results

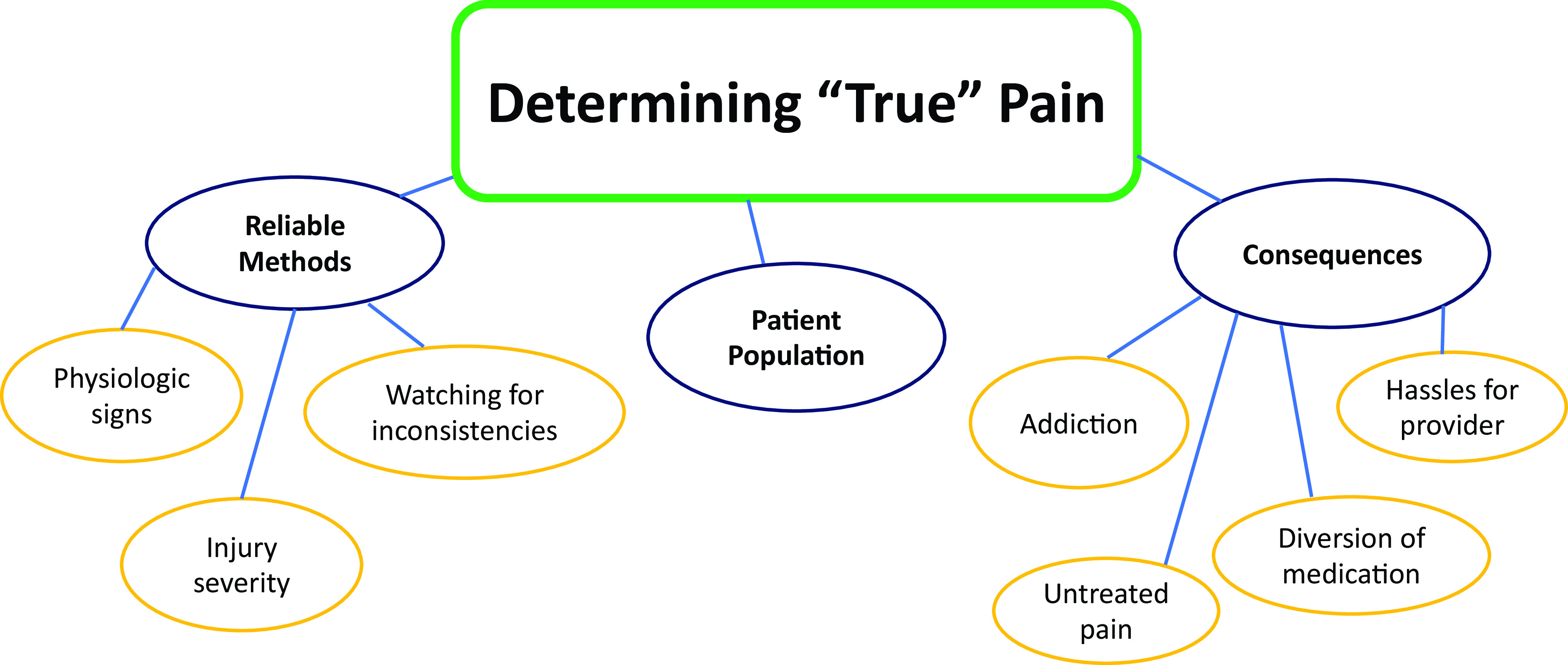

Participants identified the importance of determining “true” pain, which was the overarching theme that emerged in analysis. Subthemes included perceptions of the influence of reliable methods for pain assessment, the trustworthiness of their patient population, and the consequences of not getting it right.

Conclusions

Trauma care providers described a range of factors, beyond patient-elicited pain reports, in order to interpret their patients’ analgesic needs. These included consideration of both the risks of under treatment and unnecessary suffering, and overtreatment and contribution to opioid overdoses.

Keywords: Trauma, Injury, Pain, Opioids, Race

Background and Significance

Opioids cause as many as 130 overdose deaths per day in the United States.1 Efforts to respond to the overdose crisis include the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommendations advising health care providers to limit opioid prescribing, consult electronic prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), and consider risks for addiction and overdose related to opioids in their prescription decisions.2 Though opioid prescribing has decreased, the rate of overdose death across the United States has fallen only slightly and some states have continued to experience increases in fatal overdose rates.1,3 The persistence of the opioid overdose crisis is in part a result of widespread availability of prescription and illicit opioids on the street through which people acquire substances for recreation or pain self-treatment without a provider’s prescription.1,4,5

With increased attention on opioid prescriptions, providers who treat patients with conditions like acute injuries are increasingly conscious of balancing responsible prescribing practices with achieving analgesia so that patients can engage in therapeutic rehabilitation. A potential consequence of increasingly cautious opioid prescribing is the under-treatment of pain, which in addition to interfering with a patient’s ability to heal, may lead patients to seek opioids illicitly for self-treatment.5 At a population level, the turn toward increasingly conservative pain treatment may worsen disparities that have largely disadvantaged Black and Latinx patients6 as result of racialized perceptions of risks for addiction, diversion and pain sensitivity.

Social and relational factors influence pain prescription decisions for acute pain. In a study of emergency department (ED) physicians’ pain prescription decisions, participants emphasized the importance of the “trustworthiness” of their patients’ pain reports.7 Participants described that when making pain treatment decisions, patients’ self-report of pain are of secondary importance to providers’ beliefs about how much pain a patient’s condition would or should cause. One participant, for example, stated that he knew how much pain a kidney stone caused because he had experienced one himself.7

In determining a patient’s trustworthiness, factors like a known history of substance use or presentation with a specific kind of injury (eg, gunshot wound) may also influence pain treatment decisions, as the circumstances leading to the injury may raise provider suspicion about a patient’s involvement in criminal activity and/or risk for substance misuse or diversion.8 Much of the research about pain treatment decision-making focuses on the ED7 or the treatment of chronic pain5; however, little is known about these decision-making processes during hospital discharge planning for patients who have survived severe trauma from, for example, violent assaults. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the factors that trauma care providers take into consideration when prescribing pain treatment during discharge planning for seriously injured patients.

Methods

Research Design

In this qualitative descriptive study, we used in-depth interviews to explore the perceptions of trauma care providers who prescribe discharge analgesics and the factors they consider when planning discharge pain treatment for seriously injured patients.

Participants

We purposively recruited trauma care providers who were advanced practice providers (nurse practitioners and physician assistants) and physicians who routinely prescribe discharge analgesics at a Level I trauma center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Trauma centers with Level 1 designations can provide care addressing all trauma patients’ needs, including specialty surgical care.9 Twelve providers were interviewed between November 2018 and January 2019. The participant group consisted of seven advanced practice providers and five physicians. Participants’ average age was 41.5 years (SD: 11.1), with an average of 11.6 (SD: 7) years in practice, and 8.8 (SD: 6.6) years working in trauma care. The principal investigator (SA), a White woman, conducted all interviews. There was gender and race congruence between the interviewer and seven of the interviewees.

Procedures

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board, after which participants were recruited using multiple strategies. The study was presented at trauma department meetings where attendees were provided with study contact information through which to indicate interest in participation. This strategy yielded an initial sample of six participants, after which snowball sampling was used to recruit an additional six eligible providers.

Data collection entailed a semi-structured interview (Table 1) with structured elicitation of select demographic data and clinical experience. Participants provided verbal informed consent prior to being interviewed in private locations at their place of employment. Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted approximately 20-40 minutes. Participant recruitment and interviews continued until descriptive saturation was reached when there was consistency in how participants described their experiences and perspectives.10,11 Field notes describing important context and non-verbal aspects of interviews were recorded during and immediately following interviews. Participants were acknowledged for their participation with a $20 gift card.

Table 1. Interview guide prompts.

| 1. Tell me about how you evaluate the pain treatment needs of an injured patient who is soon to be discharged. | ||

| 2. Tell me about how you communicate with a patient regarding their pain management at the time of discharge. | ||

| 3. Other than what has already been described, what other patient factors do you consider important when you develop a pain treatment discharge plan for a patient. | ||

| a. If participant asks what is meant by “factors”: | ||

| i. Are there any patient characteristics that you consider when developing discharge plans? | ||

| ii. Are there ways in which your planning would change due to individual patient characteristics? | ||

| 4. What makes you think a patient’s pain is adequately controlled? | ||

| 5. What makes you think a patient’s pain is not adequately controlled? | ||

| 6. Have you ever been worried that a patient has left the hospital without what they needed for pain control? | ||

| 7. Tell me a situation where you were concerned about prescribing a patient an opioid at discharge. | ||

| a. What made you concerned? | ||

| b. How did you handle it? | ||

| 8. How, if in any way, has attention to the current opioid crisis impacted your discharge planning? | ||

| 9. Is there anything else you’d like to add to help me understand the dynamics of pain treatment discharge planning? | ||

| 10. Do you have social proximity to substance use and criminal behavior in your personal life? | ||

Data Management and Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, verified for accuracy, and de-identified. Interview data were imported into NVIVO software and analyzed using thematic analysis. This descriptive analytic method allows for discovery of meaningful congruencies in the experiences of providers and the ways they discuss the process of planning pain treatment for injured patients.12 It requires an inductive approach to analysis and development of a thematic schema that comes directly from the data.12

Analysis began after the first interview was transcribed and integrated with field notes denoting interview environment, participant affect and non-verbal communication. Analysis continued by a process of reading and re-reading each transcript,13 iteratively coding each interview, and creating a codebook through which to code subsequent interviews Codes were grouped into subthemes and one overarching theme based on study team discussions and consensus.

Several techniques were used to ensure the rigor and trustworthiness of analytic findings. First, field notes were used to triangulate data by adding descriptions of the non-verbal components of interviews.14 Second, the research team used debriefing and analytic discussion and a peer qualitative research collective15 to increase credibility (congruence of the participant experience with what is presented by the researcher).14 Finally, the PI documented the study process and analytic decisions integrating self-reflections throughout the data collection and data analysis phases of research.14

Results

Analysis yielded one overarching theme, labeled determining “true” pain, and three subthemes, labeled reliable methods, patient population, and consequences of not getting it right (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Major theme and subthemes.

Determining “True” Pain

The theme that emerged from interviews was the importance of determining if pain reports reflected “true” pain. Participants described their process for identifying the sincerity of pain reports on what they believed was: appropriate for the type/severity of injury; consistent with patient behavior and other physical signs; and not perceived to be fabricated for the purpose of obtaining opioids to misuse or divert.

Reliable Methods

Providers described what they interpreted as reliable methods for assessing “true” pain. They expressed that use of these methods was necessary to resist false inflation of pain self-reports. Some providers acknowledged the common practice of engaging numerical pain scales for rating pain but reported that they did not think these measures were especially helpful. Reliable methods to determine pain included evaluating the type and severity of a patient’s injury, evaluating physiologic signs such as vital signs and patient appearance, and watching for inconsistencies between a patient’s reported level of pain and their behaviors and functional capacity. For example, providers reported doubting a patient’s report of severe pain if that patient was able to eat, sleep, or socialize with visitors:

If someone’s sitting up in the bed chomping on potato chips, having conversations on the phone and their vital signs are rock solid stable, and they’re telling you that their pain is 10 out of 10, I kind of have a hard time believing that.

All providers interviewed reported a process of watching for inconsistencies between pain self-report and the aforementioned evaluation criteria. They described different techniques to uncover or validate these inconsistencies. The least invasive of these techniques involved talking with patients about the mismatch between a patient’s pain report and observed behavior:

I’ll say something like ‘Really? Cause you seem like you’re really quite comfortable sleeping there.’ ‘Oh my pain is 10 out of 10.’ ‘Well, you know I have a hard time really grasping that because I had to call your name 4 or 5 times and then shake the bed before you woke up.

Some providers reported surveilling patients without their knowledge in order to see how they behaved when they didn’t know they were being watched:

I try to peek in the room. I don’t let them close the door. Patients who want to get more narcotics will…play things up, obviously.

The most invasive example of a technique, described by only one participant, involved physically causing discomfort:

Sometimes I’ll purposely bump into the bed really hard…and see if they respond. If somebody has their leg broken…I will purposely hit it and if they don’t flinch. Another thing I’ll do for somebody who has an extremity injury in their lower leg is we’ll just push their big toe up, like while I’ll [be] talking to them I’ll just suddenly extend their big toe…it will pull on the tendons in the compartments of their leg, and if they writhe in pain then I’m like ok, that’s the real deal. Usually you can distract them and they won’t respond to it. And you’re like ok, I’m not concerned.

Patient Population

Participants expressed that it was especially important for them to be vigilant about the potential for pain rating manipulation and substance use/diversion because of the patient population they managed in their daily practice. Though some participants acknowledged a diversity of injuries and social/demographic characteristics of the patients seen in their work environment, many also suggested that there are specific tendencies that can be generalized to trauma patients:

There are some patients who will take their narcotics and sell them, absolutely. That’s totally a realistic observation that there are patients, especially patients in the trauma world, who think they can get money for these pills on the street.

Another participant, referring to patients asking for opioid analgesics, stated:

You have to be cautious with our trauma patients in the urban setting, because some of our patients are not narcotic naïve, and they do like to dictate.

While participants described seeing many patients of different ages with injuries related to falls or motor vehicle accidents, one acknowledged that violent (ie, gunshot, stabbing) injuries felt most prevalent:

It’s an urban trauma center, so although I think our numbers bore out that roughly half is penetrating trauma, some days it feels like it’s three-fourths to eighty, ninety percent penetrating trauma. So sometimes it’s a young, urban population.

Consequences of not Getting It Right

Participants expressed concern about the negative consequences of not accurately determining and treating pain. These concerns fell on two ends of a spectrum: either patients who did not need pain treatment would be prescribed opioids that could be misused, or patients experiencing pain would be undertreated. Some participants described their recent appreciation of the addictive potential of opioids in light of the severity of the opioid overdose crisis and remarked on how they had not been trained to consider the potential of substance use disorder. All participants described recognition of the risks associated with opioids and were worried about contributing to the opioid overdose crisis:

You just don’t know who’s going to turn around and sell these prescription drugs on the street. You are…helping provide drugs for people and I don’t want to do that…at the same time, it’s a very fine line, because I don’t want to not adequately treat my patients’ pain.

Some providers expressed that they had difficulty understanding how or why patients might use opioids for non-pain purposes:

I try to be as understanding as I can, but I do come from a family and a circle of friends where it’s bad if I take Tylenol…I’ve never had narcotics in my life…yeah, it impacts my view on things, in that I try really hard to understand and be sympathetic to how they got to where they are, um, but it can be a little bit hard for me to relate to sometimes like, how did you let it get this far?

Although all providers expressed concern that prescribed opioids could fuel an existing substance use disorder or result in a new misuse of opioids, two providers had a broader perspective on how and why patients use pain medications for coping with an injury:

People may be looking for medication or drugs to use not in the way or not for the reason that we intend as prescribing providers, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it’s wrong or the worst thing for them. It may be the best thing for them in some contexts. But it’s a little hard to navigate.

Another provider echoed the complex reasons why individuals use substances, while also acknowledging how substance use can make pain control difficult:

Basically it’s how you approach them. It’s non-judgmental…‘I’m not your mom, I’m not the police, what you do, you have to do to get through your day. I’m just asking you to be honest with me because I don’t want to do anything to unintentionally hurt you.’

Providers also expressed the concern that patients who needed pain treatment might not receive it. Two concerns that providers expressed were that undertreated pain would have negative health consequences for patients, and that patients in pain after discharge would create a hassle for providers. Referring to the negative health effects of undertreated pain, one participant stated:

We worry about peoples’ pain because pain is bad for people, but we also worry about their functional limitations which can sometimes be bad for their health…we want people to be able to walk so that they don’t get DVTs. When people have rib fractures we want their pain to be controlled so that they are able to breathe well enough so that they won’t get pneumonia.

Inadequately treated pain after discharge was also perceived as a hassle because patients might contact providers after discharge seeking pain treatment:

A lot of it is driven by…in a selfish way, like, when they call the doc line it’s so painful to call them back and like, listen to these usually unreasonable expectations these people have about their pain, and they are just yelling at you on the phone, it’s that same conversation, ‘if you’re that concerned come to the ED.’ It takes, you know 15 minutes of your time that you could spend much better elsewhere… So even when people say ‘I don’t want narcotics’ I still give them a script, I say ‘take the script, don’t fill it unless you want it.’

Providers acknowledged that this concern could actually lead to more prescribing, as providers might try to prevent follow-up calls by prescribing more opioids than they think patients need. A few providers noted that policies enacted to decrease prescribing could have the unintended consequence of increasing prescribing. An example is the restriction on calling in prescriptions for controlled substances; since providers know that they won’t be able to easily call in orders of opioids for patients after discharge, providers may choose to prescribe a larger number of pills at discharge:

I do worry about undershooting….I think some well-intentioned regulations can make it very challenging because if you want to send someone out with less…it’s also become much more difficult to prescribe by phone, it’s harder to send them out with less. So I think sometimes we do send them out with less than they need, and they have trouble…or we send them out with more than they should probably have to prevent that…neither of those is ideal.

Discussion

The results of this study highlight the multiplicity of factors that providers consider when prescribing discharge analgesics for patients who survive a serious injury. Providers in this study described an awareness of the risks associated with opioid use but also expressed concern about providing adequate pain control for “true pain.” True pain determination required that they triangulate patient self-rating with other methods of assessment that ranged from conversational to invasive. In general, providers also indicated that they regarded pain exaggeration as fairly common, especially in the trauma patient population, suggesting a level of skepticism for the trustworthiness of injured patients in this clinical setting that may have always existed or has emerged/worsened with growing attention to the opioid overdose crisis.

Chiarello’s work explores shifting professional roles consequent to the opioid overdose crisis and response by governmental, law enforcement, and health care agencies.16 One such shift is providers’ use of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) to determine whether patients are engaging in “doctor shopping” for controlled substances, which she argues: “has the potential to reorganize key aspects of health care by privileging punishment over treatment.”16 Although no participants voiced this kind of role shift explicitly, many noted the discomfort they feel trying to determine if patients are attempting to “trick” them into prescribing opioids through fabricated pain ratings. This echoes a finding of Sinnenberg and colleagues that none of the ED physicians they interviewed felt that patient reports of pain were helpful in guiding pain treatment decisions.7 The alternate or confirmatory pain assessment techniques reported by providers in our study, such as undisclosed surveillance and use of purposeful physical discomfort, have the potential to negatively impact the provider-patient relationship and deteriorate trust.

Our study adds a new perspective about how injured patients are viewed in health care encounters and the potential for biases to impact patient-provider relationships. Other studies have reported how violently injured Black patients feel stigmatized in health care enounters.17,18 As stated by Patton et al: “The stream of wounded young people may perpetuate the stereotypes about gunshot victims as gang-members, drug dealers, or individuals whose lifestyle choices caused their injures,”17 suggesting that patients with specific kinds of injuries may be at particular risk for stigmatization as providers assume that patient behaviors led to injuries.

Providers in our study did not explicitly describe feelings of mistrust toward any specific type of trauma patient, but they did perceive that the trauma population comprises patients more likely to exaggerate pain ratings. Many also described their patient population as “urban,” which may be a rhetorical strategy to avoid explicitly racialized language but to nonetheless confer social and racial meaning.19,20 While the hospital at which these providers work is in a large city, the word “urban” to describe patient populations is rarely used for city-dwelling upper-middle class and/or White populations.21,22 Participants did not discuss race explicitly, and it is possible that they were not fully aware of what their word choice implied. However, in the context of participants’ beliefs that patients were likely to misuse medication due to the fact that they were “urban,” it suggests that participants were attempting to portray something about their patients beyond the fact that they are city-dwelling. These findings prompt the need for further evaluation of the language used by health care providers to describe patients and whether such language results in differences in care and how it may be reinforced by clinical training and clinical culture.23

Participants in our study expressed concern about the consequences of system- and policy-level efforts to curb opioid prescribing. Especially notable were regulations controlling electronic/phone prescribing and how these result in providers prescribing more opioids than necessary in an effort to avoid both adverse outcomes for their patients (undertreated pain) and provider hassles (responding to patient calls). This echoes the findings of Habbouche and colleagues, who discovered that the rescheduling of hydrocodone and limitations on telephone/facsimile prescribing were associated with an increase in the number of pills prescribed after surgery.24 Many have also highlighted the unintended consequences of regulations that result in pain undertreatment including withdrawal following rapid tapers in opioid maintained patients, use of illicit opioids from the street to replace discontinued prescriptions, provider avoidance of patients deemed too risky due to long-term opioid use, and patient suicides related to untreated pain.25-28 Our findings highlight the need to critically examine the potential unintended consequences of opioid control efforts in the aftermath of acute hospitalization for serious injuries.

Given that most traumatic injuries will cause patients to experience acute and potentially chronic pain, and that overdose death in North America is increasingly driven by the lethality of street drug supplies tainted with illicit fentanyl,29,30 clinical practice and institutional opioid prescription policies must acknowledge patient pain in balance with the risks of unneeded opioid prescriptions, the dangers of unmanaged pain, and the potential for risky self-treatment. This could include mandatory documentation of how patient pain ratings are elicited during hospitalization and at discharge (whether verbal, physical, or if a determined based on reports from other clinicians and/or patient surveillance) and a plan for post-discharge pain assessment and management. Current practice may also benefit from policies that require continuing education on evolving paradigms in the management of acute and chronic pain related to trauma and in light of the current state of opioid prescription norms and the overdose crisis.

Participants’ statements reflecting their feelings about the unreliability of patient-reported numerical pain scales further suggest the need for quality improvement and related research on pain measurement and treatment algorithms for trauma care providers. In addition, the expressed belief that the “urban” trauma population comprises patients more likely to exaggerate pain ratings suggests the need to comprehensively address biases in trauma care and particularly at trauma centers serving communities of color. Policies that make the health professional school pipelines more accessible and less discriminatory are vital in this effort.31 Additionally, hospitals might consider implementing programs mirroring those that employ community health workers32 or peer support specialists,33 tailored to serve patients hospitalized for traumatic injury. These programs would pair patients with a trained peer who has lived experiences of trauma and can facilitate communication between the patient and care team, as well as advocate for the patient and their needs.

Study Limitations

This study has several limitations including a lack of institutional variation in study recruitment. Providers’ pain management choices may be influenced by the other providers at their place of employment as well as institutional norms. The experiences of providers in this study may differ from those of providers who work in different social and geographical contexts where violence and violent injuries are less common. The purpose of this research, however, was not generalizability, but rather an in-depth description of how and why trauma providers make opioid prescription decisions. Future work in this area would be strengthened by a diversified perspective that includes providers from a variety of institutional settings.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide important insight into the impacts of the opioid overdose crisis and attempts to address it in patient-provider relationships and pain treatment. Participants voiced numerous concerns related to prescribing opioid pain treatment, chief among them was the ability to determine “true” pain. Participants described a variety of methods they deem reliable to determine a patients’ pain level and believe that these methods are especially important given the population of patients they treat, who they perceive as high risk for fabricating pain reports. Providers in this study considered the many consequences of misjudging a patient’s pain, which included both under treatment and unnecessary suffering, as well as overtreatment and contributing to the opioid overdose crisis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars Fellowship; and by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health (grant R01NR013503 [Dr. Richmond]).

References

- 1.Gitis B, Soto I.. The Types of Opioids behind the Growing Overdose Fatalities. American Action Forum; 2018. Last accessed October 22, 2020 from https://www.americanactionforum.org/print/?url=https://www. americanactionforum.org/research/types-opioids-behind-growing-overdose-fatalities/.

- 2.Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain -- United States 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016; 65(No. RR- 1):1-49 http://dx.doi.org/ 10.15585/mmwr. rr6501e1external icon [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ahmad F, Escobedo L, Rossen L, Spencer M, Warner M, Sutton P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. Washington, DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alford DP, German JS, Samet JH, Cheng DM, Lloyd-Travaglini CA, Saitz R. Primary care patients with drug use report chronic pain and self-medicate with alcohol and other drugs. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(5):486-491. 10.1007/s11606-016-3586-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matthias MS, Talib TL, Huffman MA. Managing chronic pain in an opioid crisis: what is the role of shared decision-making? Health Commun. 2020;35(10):1239-1247. 10.1080/10410236.2019.1625000 10.1080/10410236.2019.1625000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinnenberg LE, Wanner KJ, Perrone J, Barg FK, Rhodes KV, Meisel ZF. What factors affect physicians’ decisions to prescribe opioids in emergency departments? MDM Policy Pract. 2017;2(1):2381468316681006. 10.1177/2381468316681006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronowitz SV, Mcdonald CC, Stevens RC, Richmond TS. Mixed studies review of factors influencing receipt of pain treatment by injured black patients. J Adv Nurs. 2020;76(1):34-46. 10.1111/jan.14215 10.1111/jan.14215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Trauma Society Trauma Center Designations and Levels. January 2000. Palo Alto, CA: Brain Trauma Foundation. Last accessed October 22, 2020 from https://braintrauma.org/news/article/trauma-center-designations.

- 10.Morse JM. “Data were saturated . . . ”. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(5):587-588. 10.1177/1049732315576699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52(4):1893-1907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. In: Cooper H, ed. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Vol 2 Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16(1):1-13. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abboud S, Kim SK, Jacoby S, et al. Co-creation of a pedagogical space to support qualitative inquiry: an advanced qualitative collective. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;50:8-11. 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiarello E. The war on drugs comes to the pharmacy counter: frontline work in the shadow of discrepant institutional logics. Law Soc Inq. 2015;40(01):86-122. 10.1111/lsi.12092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patton D, Sodhi A, Affinati S, Lee J, Crandall M. Post-discharge needs of victims of gun violence in Chicago: A qualitative study. J Interpers Violence. 2019;34(1):135-155. 10.1177/0886260516669545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rich J. Wrong Place, Wrong Time: Trauma and Violence in the Lives of Young Black Men. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonilla-Silva E. Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. 5th ed Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonilla-Silva E. The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. Am Behav Sci. 2015;59(11):1358-1376. 10.1177/0002764215586826 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurwitz J, Peffley M. Playing the race card in the post-Willie Horton era: the impact of racialized code words on support for punitive crime policy. Public Opin Q. 2005;69(1):99-112. 10.1093/poq/nfi004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kooragayala S. The problem with talking about “inner cities.” Urban Institute. November 3, 2016. Last accessed October 22, 2020 from https://www.urban.org/2016-analysis/problem-talking-about-inner-cities.

- 23.Changoor NR, Udyavar NR, Morris MA, et al. Surgeons’ perceptions toward providing care for diverse patients: the need for cultural dexterity training. Ann Surg. 2019;269(2):275-282. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habbouche J, Lee J, Steiger R, et al. Association of hydrocodone schedule change with opioid prescriptions following surgery. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(12):1111-1119. 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demidenko MI, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Meath THA, Ilgen MA, Lovejoy TI. Suicidal ideation and suicidal self-directed violence following clinician-initiated prescription opioid discontinuation among long-term opioid users. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;47:29-35. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dowell D, Haegerich T, Chou R. No shortcuts to safer opioid prescribing. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2285-2287. 10.1056/NEJMp1904190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nam YH, Shea DG, Shi Y, Moran JR. State prescription drug monitoring programs and fatal drug overdoses. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(5):297-303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothstein MA. The opioid crisis and the need for compassion in pain management. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8):1253-1254. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303906 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H IV, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—united States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services. As fentanyl ODs have surged in Philly, price of antidote has tripled. DBHIDS in the News. August 22, 2015. Last accessed October 22, 2020 from https://dbhids.org/blog/tag/fentanyl/.

- 31.Lynch G, Holloway T, Muller D, Palermo AG. Suspending student selections to Alpha Omega Alpha medical honor society: how one school is navigating the intersection of equity and wellness. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):700-703. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hartzler AL, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Wagner EH. Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):240-245. 10.1370/afm.2208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myrick K, Del Vecchio P. Peer support services in the behavioral healthcare workforce: state of the field. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2016;39(3):197-203. 10.1037/prj0000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]