Abstract

Background:

Burnout and distress negatively affect the well-being of health care professionals and the treatment they provide. Our aim was to measure the prevalence of burnout and distress among allied health care staff at a cardiovascular centre of a quaternary hospital network in Canada, and compare outcomes to those for nonphysician employees in the United States.

Methods:

We conducted a survey of allied health care staff, including physical, respiratory and occupational therapists, pharmacists, social workers, dietitians and speech-language pathologists, in a cardiovascular centre at 2 quaternary referral hospitals in Toronto, Ontario, between Nov. 27, 2018, and Jan. 31, 2019. The survey tool included the Well-Being Index (WBI), which measures fatigue, depression, burnout, anxiety or stress, quality of life, work–life integration, meaning in work and overall distress; a score of 2 or higher indicated high distress. We carried out standard univariate statistical comparisons using the χ2, Fisher exact or Kruskal–Wallis test as appropriate to perform univariate comparisons in the sample of respondents. We assessed the relation between a WBI score of 2 or higher and demographic characteristics. We compared univariate associations among WBI data for nonphysician employees in the US who completed the WBI to responses from our participants.

Results:

The response rate to the survey was 86% (45/52). Thirty-three respondents (73%) reported experiencing burnout in the previous month, and 31 (69%) reported emotional problems. Compared to respondents who perceived fair treatment in the workplace, those who perceived unfair treatment (20 [44%]) were more likely to report emotional problems (17 [85%] v. 13 [54%], p = 0.05), to worry that work was hardening them emotionally (15 [75%] v. 8 [33%], p = 0.008), and to feel down, depressed or hopeless (12 [60%] v. 4 [17%], p = 0.005). Twenty-five respondents (56%) and 13 respondents (29%) reported WBI scores consistent with high (≥ 2) or severe (≥ 5) distress, respectively. Respondents were more likely to have a high WBI score if they perceived unfair treatment or inadequate staffing levels. Our respondents had a higher prevalence of burnout (73.3% v. 53.6%, p = 0.008) and a higher average WBI score (2.6 [SD 2.8] v. 1.7 [SD 2.6], p = 0.05) than 9096 nonphysician employees in the US.

Interpretation:

The prevalence of burnout, emotional problems and distress was high among allied health care staff. Fair treatment in the workplace and adequate staffing may lower distress levels and improve the work experience of these health care professionals.

Burnout is a work-related syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, a sense of reduced personal accomplishment and depersonalization that may manifest as negativity, cynicism, and the inability to express empathy or grief.1–3 The term burnout was first used in a medical context by Freudenberger,4 who described emotional depletion and loss of motivation and commitment that he and others had observed and experienced. Maslach and colleagues1,3 subsequently noted that the emotional stress human services workers experienced and their coping strategies had important implications for people’s professional identity and job behaviour.

Burnout adversely affects the quality of care that health care workers provide, and correlates with an increased risk of medical errors, serious safety events, malpractice proceedings, reduced patient satisfaction and worse patient outcomes.5–10 Health care workers are at high risk for mental health issues, including anxiety, depression and suicide.11,12

Although many studies have focused on the prevalence and causes of burnout and distress in nurses6,13–15 and physicians, 16–18 comparatively fewer studies have addressed these issues among allied health care staff, including pharmacists19,20 and physical,21 respiratory22 and occupational23,24 therapists. The aim of this research was to measure the prevalence of burnout and overall distress among allied health care staff practising in a cardiovascular centre of a quaternary hospital network.

Methods

Design, setting and recruitment

We conducted a survey at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre (PMCC), which is the cardiovascular centre for University Health Network in Toronto, Ontario. It is based at 2 quaternary referral hospitals: Toronto General Hospital and Toronto Western Hospital. The survey was open to all PMCC allied health staff, including physical, respiratory and occupational therapists, pharmacists, social workers, dietitians and speech-language pathologists.

The survey was conducted between Nov. 27, 2018, and Jan. 31, 2019. Posters describing the survey were placed in multiple areas across the 2 sites (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E29/suppl/DC1). An independent third party (Canadian Viewpoint, https://canview.com/) sent an initial email invitation (Appendix 2, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E29/suppl/DC1) and subsequent reminders to complete the survey to all allied health care staff practising in the PMCC. Neither the University Health Network nor the authors had access to individual responses to the survey, which were collected by Corporate Web Services (https://www.cws.net/).

Survey tool

Multiple surveys can be used to assess burnout, well-being and other work-related dimensions of distress, including the Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel,1–3 the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, the single-item measure used in the Physician Worklife Study, the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, the Stanford Professional Fulfillment Index, the Well-Being Index (WBI)25,26 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 of the self-report component of the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders inventory. The validity and reliability of these survey instruments, including consideration of the format, source of data, development and testing, links to outcomes or health system characteristics related to health care professionals, past or validated applications, and cost, have been reported.27

After reviewing all these validated survey instruments, we chose to use the WBI because it has a core of only 9 questions, takes only minutes to complete, provides instantaneous and confidential feedback to survey participants, and has been independently validated for use in a diverse group of employees and health care professionals, including physicians, nurses and nonphysician employees.25,26,28,29 Use of the WBI also enabled comparison of our results to a large (n = 9096) group of nonphysician employees in the United States, in whom a WBI score of 2 or higher identified employees with high levels of overall distress.26 The WBI can also identify employees who are doing well (high overall quality of life, high degree of meaning in work, satisfied with work–life balance) and employees whose degree of distress increases the risk of adverse professional consequences.26

Seven of the 9 WBI items are questions that are answered “Yes” or “No,” with 1 point assigned for each “Yes” response.

Responses to the statement “The work I do is meaningful to me” were based on the Empowerment at Work Scale30 (7-point Likert scale where 1 = very strongly disagree and 7 = very strongly agree). Respondents who indicated 1 or 2 on the Likert scale had 1 point added to their score, and those who indicated 6 or 7 on the Likert scale had 1 point subtracted from their score.

Respondents indicated their level of agreement with the statement “My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life” on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Respondents who indicated lower satisfaction with work–life integration (i.e., 1 or 2 on the Likert scale) had 1 point added to their score, and those who indicated higher satisfaction (i.e., 4 or 5 on the Likert scale) had 1 point subtracted from their score.

Accordingly, the total score for the WBI ranged from −2 to 9.

We also asked survey participants to supply demographic information and respond to 3 additional statements designed to assess work culture (“Please rate your satisfaction with your electronic health record,”31 “The staffing levels in this work setting are sufficient to handle the number of patients” and “I am treated fairly in the workplace”). Respondents indicated their level of agreement with the 3 statements on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. The full survey tool is presented in Appendix 3 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E29/suppl/DC1).

Feedback

On completion of the survey, respondents received instantaneous feedback via email in the form of a dashboard from the survey administrator that quantified each dimension of distress. If a WBI score indicative of distress (i.e., ≥ 2) was identified, the email response to individual study participants included the information required to access local, regional and provincial resources that provide assistance managing stress and resilience, fatigue, emotional concerns, suicidal thoughts, issues related to relationships and work–life balance, and alcohol or substance abuse.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the relation between responses to individual WBI questions and participants’ gender, years in practice, area of practice, satisfaction with the hospital’s electronic health record, perception of the adequacy of staffing levels, perception of being treated fairly in the workplace, work–life integration and meaningful work. We assessed demographic and environmental factors that predicted respondents’ WBI scores, and compared their responses to the WBI scores of nonphysician employees in the US who completed the WBI.26 We also recorded the number of times respondents accessed contact information for local, regional or provincial resources after they received feedback.

We carried out standard univariate statistical comparisons using the χ2 test when expected counts were 5 or greater, the Fisher exact test when expected counts were less than 5 and the Kruskal–Wallis test for nonparametric continuous variables to perform univariate comparisons in the sample of respondents. We assessed selected demographic and work culture items and elements of the WBI survey, both between and within groups. We also assessed the relation between a WBI score of 2 or higher and demographic characteristics, as well as responses to statements about work culture. Finally, we compared univariate associations among WBI data for nonphysician employees in the US26 with responses from our participants. We conducted all analyses using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute).

Ethics approval

The University Health Network Research Ethics Board provided a waiver for the requirement for research ethics approval for this study (waiver 18-0246).

Results

Of the 52 allied health care staff invited to participate in the survey, including 17 pharmacists, 11 respiratory therapists, 6 physical therapists, 6 dietitians, 5 occupational therapists, 4 social workers and 3 speech-language pathologists, 45 (86%) responded. We report the respondents’ gender, years since graduation, years working at University Health Network, primary practice location and employment status (full-time, part-time, casual) in Table 1. Given the total small number of allied health staff we identified in the PMCC (52), and the small number of employees in each discipline (3–17), we did not ask allied health care staff to identify their area of specialization, to ensure confidentiality.

Table 1:

Characteristics of allied health care staff who responded to the Well-Being Index survey

| Characteristic | No. (%) of respondents n = 45 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 3 (7) |

| Female | 41 (91) |

| Missing | 1 (2) |

| Time since graduation in field, yr | |

| < 2 | 1 (2) |

| 2–5 | 10 (22) |

| 6–10 | 10 (22) |

| 11–15 | 11 (24) |

| > 15 | 13 (29) |

| Time working at University Health Network, yr | |

| < 2 | 3 (7) |

| 2–5 | 12 (27) |

| 6–10 | 10 (22) |

| 11–15 | 9 (20) |

| > 15 | 11 (24) |

| Employment status | |

| Full-time permanent | 39 (87) |

| Part-time permanent | 4 (9) |

| Casual, temporary, other | 2 (4) |

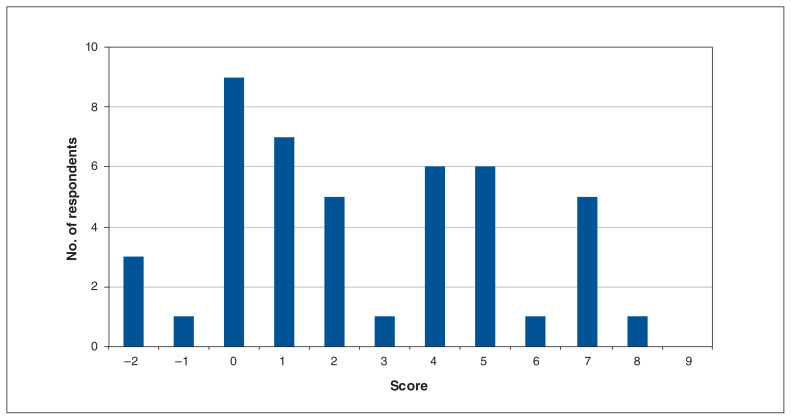

The mean WBI score for all respondents was 2.6 (standard deviation [SD] 2.8). Figure 1 shows the distribution of WBI scores.

Figure 1:

Well-Being Index scores for 45 allied health care staff in the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre.

Almost three-quarters of respondents (33 [73%]) reported that, during the previous month, they felt burned out from their work, almost one-third (31 [69%]) noted they were bothered by emotional problems, and 17 (38%) reported falling asleep while sitting inactive in a public place. Almost half (21 [47%]) agreed or strongly agreed that their work schedule left them enough time for their personal life. Male respondents appeared to have a lower rate of burnout than female respondents (0/3 v. 32/41 [78%], p = 0.02]. Responses to the remaining survey questions are presented in Appendix 4 (available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E29/suppl/DC1).

Just over half (24 [53%]) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they were treated fairly in the workplace. Compared to those respondents, the 20 respondents (44%) who somewhat or strongly disagreed that they were treated fairly in the workplace were more likely to report emotional problems (17 [85%] v. 13 [54%], p = 0.05), to worry that work is hardening them emotionally (15 [75%] v. 8 [33%], p = 0.008), and to feel down, depressed or hopeless (12 [60%] v. 4 [17%], p = 0.005).

The 33 respondents (73%) who reported that the work they did was meaningful to them were more likely to be somewhat or very satisfied than to be neutral or unsatisfied with the electronic health record (17/18 [94%] v. 16/26 [62%], p = 0.04) and to somewhat or strongly agree than to be neutral or disagree that they were treated fairly in the workplace (21/24 [88%] v. 12/20 [60%], p = 0.05). They were less likely to somewhat or strongly agree than to be neutral or disagree that staffing levels in the work setting were sufficient (3/8 [38%] v. 30/36 [83%], p = 0.02).

Univariate analysis did not identify any associations between years since completion of graduate training, years working at University Health Network or employment status and any of the individual survey questions.

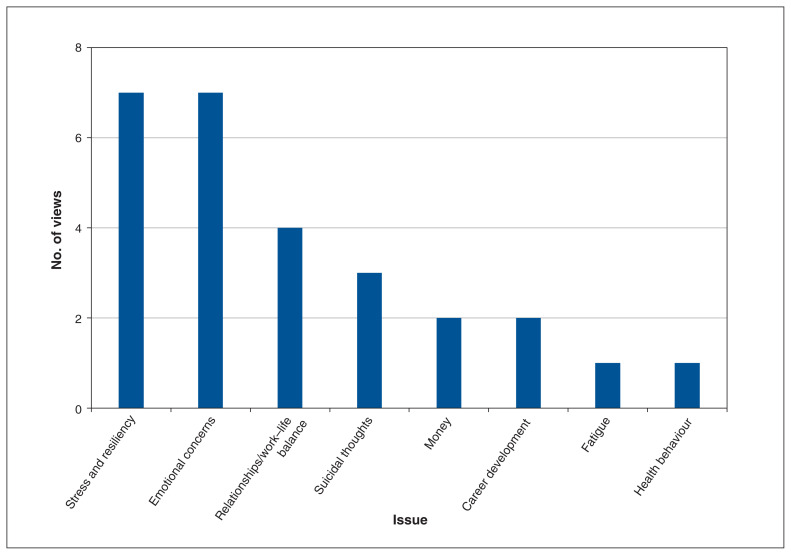

The number of times respondents accessed contact information for local, regional or provincial resources that help manage stress, emotional concerns, relationships and work– life balance, suicidal thoughts, finances, career development, fatigue and health behaviour is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

Number of views of online resources by respondents, by issue.

Predictors of high scores

Twenty-five respondents (56%) had a WBI score of 2 or higher, and 13 (29%) had a score of 5 or higher (Figure 1). Respondents were more likely to have a WBI score of 2 or higher if they were neutral or disagreed than if they agreed or strongly agreed that they were treated fairly in the workplace (15/24 [62%] v. 9/24 [38%], p = 0.02) (Table 2). Respondents were also more likely to have a WBI score of 2 or higher if they were neutral or disagreed than if they agreed or strongly agreed that staffing levels in the work setting were sufficient (17/24 [71%] v. 7/24 [29%], p = 0.05). We did not identify any relation between a WBI score of 2 or higher and gender, years since completion of graduate training, years working at University Health Network, employment status, primary practice location or satisfaction with the electronic health record.

Table 2:

Predictors of high Well-Being Index score (≥ 2)

| Variable | No. (%) of respondents | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBI score ≥ 2 n = 25 |

WBI score < 2 n = 20 |

||

| Gender | 0.6 | ||

| Male | 1 (4) | 2 (10) | |

| Female | 23 (92) | 18 (90) | |

| Missing | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Time since graduation in field, yr, | 0.8 | ||

| < 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| 2–5 | 6 (24) | 4 (20) | |

| 6–10 | 6 (24) | 4 (20) | |

| 11–15 | 7 (28) | 4 (20) | |

| > 15 | 6 (24) | 7 (35) | |

| Time working at University Heath Network, yr | 0.6 | ||

| < 2 | 1 (4) | 2 (10) | |

| 2–5 | 8 (32) | 4 (20) | |

| 6–10 | 7 (28) | 3 (15) | |

| 11–15 | 4 (16) | 5 (25) | |

| > 15 | 5 (20) | 6 (30) | |

| Employment status | 0.4 | ||

| Full-time permanent | 23 (92) | 16 (80) | |

| Part-time permanent | 2 (8) | 2 (10) | |

| Casual, temporary, other | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | |

| Satisfaction with electronic health record | 0.05 | ||

| Very unsatisfied | 2 (8) | 5 (25) | |

| Somewhat unsatisfied | 9 (36) | 1 (5) | |

| Neutral | 5 (20) | 4 (20) | |

| Somewhat satisfied | 8 (32) | 9 (45) | |

| Very satisfied | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | |

| Missing | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Somewhat/very satisfied with electronic health record (v. neutral/unsatisfied)† | 0.4 | ||

| Yes | 8 (44) | 10 (56) | |

| No | 16 (62) | 10 (38) | |

| Missing | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Staffing levels in work setting are sufficient | 0.06 | ||

| Disagree strongly | 8 (32) | 3 (15) | |

| Disagree somewhat | 8 (32) | 13 (65) | |

| Neutral | 1 (4) | 3 (15) | |

| Agree somewhat | 6 (24) | 1 (5) | |

| Agree strongly | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Missing | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Somewhat/strongly agree that staffing levels in work setting are sufficient (v. neutral/disagree)† | 0.05 | ||

| Yes | 7 (88) | 1 (12) | |

| No | 17 (47) | 19 (53) | |

| Missing | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| Treated fairly in workplace | 0.1 | ||

| Disagree strongly | 5 (20) | 3 (15) | |

| Disagree somewhat | 6 (24) | 1 (5) | |

| Neutral | 4 (16) | 1 (5) | |

| Agree somewhat | 7 (28) | 10 (50) | |

| Agree strongly | 2 (8) | 5 (25) | |

| Missing | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Somewhat/strongly agree treated fairly in workplace (v. neutral/disagree)† | 0.02 | ||

| Yes | 9 (38) | 15 (62) | |

| No | 15 (75) | 5 (25) | |

| Missing | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | |

Note: WBI = Well-Being Index.

Fisher exact test.

Proportion of row total.

Comparison with nonphysician employees in the United States

Our respondents had a higher average WBI score than 9096 nonphysician employees in the US (2.6 [SD 2.8] v. 1.7 [SD 2.6], p = 0.05). Higher proportions of our respondents reported burnout (73% v. 54%, p = 0.008), were worried that work was hardening them emotionally (53% v. 34%, p = 0.007), reported falling asleep while sitting inactive in a public place (36% v. 13%, p < 0.001) and reported that their physical health interfered with their ability to do their daily work (36% v. 21%, p < 0.02) (Table 3). Similar proportions of the 2 groups had a WBI score of 2 or higher (56% v. 51%, p = 0.5).

Table 3:

Comparison of responses to the Well-Being Index between Peter Munk Cardiac Centre allied health care staff and nonphysician employees in the United States26

| Item | No. (%) of respondents* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PMCC allied health care staff n = 45 |

US nonphysician employees n = 9096 |

||

| Gender | 0.07§ | ||

| Male | 3 (7) | 1903 (20.9) | |

| Female | 41 (91) | 7163 (78.7) | |

| Gender diverse | 0 (0) | 16 (0.2) | |

| Missing | 1 (2) | 14 (0.2) | |

| Have you felt burned out from your work? | 0.008§ | ||

| Yes | 33 (73) | 4871 (53.6) | |

| No | 12 (27) | 4225 (46.4) | |

| Have you worried that work is hardening you emotionally? | 0.007§ | ||

| Yes | 24 (53) | 3118 (34.3) | |

| No | 21 (47) | 5978 (65.7) | |

| Have you often felt bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless? | 0.99§ | ||

| Yes | 17 (38) | 3435 (37.8) | |

| No | 28 (62) | 5661 (62.2) | |

| Have you fallen asleep while sitting inactive in a public place? | < 0.001§ | ||

| Yes | 16 (36) | 1143 (12.6) | |

| No | 29 (64) | 7953 (87.4) | |

| Have you felt that all things you had to do were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? | 0.8§ | ||

| Yes | 19 (42) | 3625 (39.8) | |

| No | 26 (58) | 5471 (60.1) | |

| Have you been bothered by emotional problems? | 0.2§ | ||

| Yes | 31 (69) | 5364 (59.0) | |

| No | 14 (31) | 3732 (41.0) | |

| Has your physical health interfered with your ability to do your daily work at home and/or away from home? | 0.02§ | ||

| Yes | 16 (36) | 1917 (21.1) | |

| No | 29 (64) | 7179 (78.9) | |

| The work I do is meaningful to me† | 0.2¶ | ||

| Mean rating ± SD | 5.8 ± 1.11 | 5.5 ± 1.44 | |

| Median rating (range) | 6 (2 to 7) | 6 (1 to 7) | |

| The work I do is meaningful to me, rating | 0.09§ | ||

| 1–2 | 1 (2) | 463 (5.1) | |

| 3–5 | 10 (22) | 3199 (35.2) | |

| 6–7 | 34 (76) | 5434 (59.7) | |

| My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life‡ | 0.2¶ | ||

| Mean rating ± SD | 3.2 ± 1.25 | 3.5 ± 1.18 | |

| Median rating (range) | 3 (1 to 5) | 4 (1 to 5) | |

| My work schedule leaves me enough time for my personal/family life, rating | 0.5§ | ||

| 1–2 | 14 (31) | 2183 (24.0) | |

| 3 | 10 (22) | 2088 (23.0) | |

| 4–5 | 21 (47) | 4825 (53.0) | |

| WBI score | 0.05¶ | ||

| Mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 2.78 | 1.7 ± 2.62 | |

| Median (range) | 2 (−2 to 8) | 2 (−2 to 9) | |

| High WBI score (≥ 2) | 0.5§ | ||

| Yes | 25 (56) | 4637 (51.0) | |

| No | 20 (44) | 4459 (49.0) | |

Note: PMCC = Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, SD = standard deviation, WBI = Well-Being Index.

Except where noted otherwise.

Rated on a 7-point Likert scale where 1 = very strongly disagree and 7 = very strongly agree.

Rated on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree.

χ2 test.

Kruskal–Wallis test.

Interpretation

In this study, 73% of allied health care staff practising in the PMCC reported burnout in the previous month, and 69% reported emotional problems. Over half (56%) had a WBI score of 2 or higher, and 29% had a score of 5 or higher. Respondents were more likely to have a high WBI score if they perceived unfair treatment in the workplace or disagreed that staffing levels were sufficient.

A WBI score of 2 or higher identified allied health care staff with high levels of overall distress because such scores were associated with a 1.2-fold higher likelihood of poor overall quality of life, 1.2-fold higher likelihood of severe fatigue, 1.3-fold higher likelihood of recent suicidal ideation and 1.3-fold higher likelihood of burnout in the sample of nonphysician employees in the US.26 Analysis of that cohort showed that a WBI score of 2 or higher equated to a 34% probability of burnout.26 We interpreted a WBI score of 5 or higher to indicate severe distress among our respondents because such scores are associated with a 2.3-fold higher likelihood of severe fatigue, 2.9-fold higher likelihood of poor overall quality of life, 3.2-fold higher likelihood of recent suicidal ideation and 5.7-fold higher likelihood of burnout among nonphysician employees.26 A WBI score of 5 or higher equated to a 69% probability of burnout in that group.26 This is relevant, because workplace burnout, as well as organizational climate and job stress, are predictors of job retention among some allied health care staff.19 The finding that more than half of our respondents had high WBI scores and more than a quarter had scores consistent with severe distress strongly suggests that burnout and overall distress are having a negative impact on the careers of allied health care staff in the PMCC, their well-being and the patient care that they provide.5–10

Our respondents were more likely to find their work to be meaningful if they were satisfied with the electronic health record. Although finding meaning in work may mitigate the relation between job-related stress and psychologic distress, 32–34 we did not identify any correlation between satisfaction with the electronic health record and the prevalence of burnout or overall distress.

We plan to use the prevalence of burnout and distress identified in this study as a baseline to evaluate the efficacy of interventions designed to decrease burnout and distress among allied health care staff in the PMCC. These interventions may include individual-focused approaches such as mindfulness training, stress management and small-group discussions.35 Structural or organizational strategies, such as changes in work schedules, fostering communication between members of health care teams, and cultivating a sense of teamwork and job control,36,37 as well as professional coaching sessions,38 could also be implemented. Our results suggest that interventions to decrease distress among these professionals should focus on addressing unfair treatment in the workplace and inadequate staffing levels.

The PMCC functions as an integrated program that includes allied health care professionals, nurses, nurse practitioners, cardiac and vascular surgeons, cardiovascular anesthesiologists, cardiologists, cardiac rehabilitation physicians and medical imaging physicians who focus on the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. In concurrent studies, we noted that levels of burnout were also high among physicians (66%) and nurses (79%) in the PMCC.39,40 The 78% of PMCC nurses with a high WBI score were more likely to perceive insufficient staffing levels or unfair treatment in the workplace, and to be dissatisfied with the electronic health record.40 Similarly, the 55% of physicians in the PMCC with a high WBI score were more likely to perceive insufficient staffing levels or unfair treatment in the workplace.39 These findings, combined with the results of this study, identify the perception of unfair treatment and of inadequate staffing levels as common institutional factors that drive burnout and overall distress among health care professionals in the PMCC.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Study participants were restricted to allied health care staff practising in the area of cardiovascular medicine and surgery in 2 quaternary referral hospitals, which could limit the generalizability of our results. The relatively modest number of respondents may limit study validity and makes type 2 statistical errors more likely. The low number of male respondents limited our ability to compare their results with those of the female respondents. The previously described supplemental survey questions that relate to the perception of the adequacy of staffing levels, fair treatment in the workplace and satisfaction with the electronic health record were not subject to pilot evaluation in this study. The 9096 nonphysician employees in the cohort of respondents to the WBI survey in the US26 represent a variety of professions, which limited our ability to compare WBI scores directly with a group of allied health care professionals in the PMCC. Finally, the limited number of respondents to our survey precluded multivariable analysis of the data.

Conclusion

The perception of inadequate staffing levels and unfair treatment in the workplace predicted higher levels of overall distress among allied health care staff. Initiatives that focus on addressing these institutional factors might lower distress levels and burnout among allied health care staff in the PMCC and improve their work experience and patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Liselotte Dyrbye, Professor of Medical Education and Professor of Medicine, Division of Community Internal Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, and Danielle Martin, Executive Vice President and Chief Medical Executive, Women’s College Hospital, for very helpful discussions.

See related research articles at www.cmajopen.ca/lookup/doi/10.9778/cmajo.20200057 and www.cmajopen.ca/lookup/doi/10.9778/cmajo.20200058

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Barry Rubin, Rebecca Goldfarb and Leanna Graham designed the study. Daniel Satele carried out the statistical analysis. Barry Rubin drafted the manuscript. All of the authors contributed to the study conception, analyzed and interpreted the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: A grant from the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre Innovation Fund supported this work.

Data sharing: All data presented in this manuscript are available to other investigators on request from the corresponding author.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/9/1/E29/suppl/DC1.

Disclaimer: The funding group had no role in the design, conduct or implementation of the study, or the decision to submit, preparation of and editing of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout InventoryTM manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto (CA): Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dzau VJ, Kirch DG, Nasca TJ. To care is human — collectively confronting the clinician-burnout crisis. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:312–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1715127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freudenberger H. The staff burnout syndrome in alternative institutions. Psychotherapy (Chic) 1975;12:72–83. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, et al. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakhamis L, Paul DP, 3rd, Smith H, et al. Still an epidemic: the burnout syndrome in hospital registered nurses. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2019;38:3–10. doi: 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:657–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1317–31. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 9.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1571–80. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welp A, Meier LL, Manser T. Emotional exhaustion and workload predict clinician-rated and objective patient safety. Front Psychol. 2015;5:1573. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutheil F, Aubert C, Pereira B, et al. Suicide among physicians and health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jollant F, Hawton K, Vaiva G, et al. Non-presentation at hospital following a suicide attempt: a national survey. Psychol Med. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spence Laschinger HK, Wong C, Read E, et al. Predictors of new graduate nurses’ health over the first 4 years of practice. Nurs Open. 2018;6:245–59. doi: 10.1002/nop2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Brien-Pallas L, Murphy GT, Shamian J, et al. Impact and determinants of nurse turnover: a pan-Canadian study. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18:1073–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.2020 NSI national health care retention & RN staffing report. East Petersburg (PA): NSI Nursing Solutions; 2020. [accessed 2020 Mar. 9]. Available: www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Documents/Library/NSI_National_Health_Care_Retention_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work–life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–85. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251:995–1000. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516–29. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durham ME, Bush PW, Ball AM. Evidence of burnout in health-system pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018;75(Suppl 4):S93–100. doi: 10.2146/ajhp170818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lan YL, Huang WT, Kao CL, et al. The relationship between organizational climate, job stress, workplace burnout, and retention of pharmacists. J Occup Health. 2020;62:e12079. doi: 10.1002/1348-9585.12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.González-Sánchez B, González López-Arza MV, Montanero-Fernández J, et al. Burnout syndrome prevalence in physiotherapists. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2017;63:361–5. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.04.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shelledy DC, Mikles SP, May DF, et al. Analysis of job satisfaction, burnout, and intent of respiratory care practitioners to leave the field or the job. Respir Care. 1992;37:46–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta S, Paterson ML, Lysaght RM, et al. Experiences of burnout and coping strategies utilized by occupational therapists. Can J Occup Ther. 2012;79:86–95. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2012.79.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards H, Dirette D. The relationship between professional identity and burnout among occupational therapists. Occup Ther Health Care. 2010;24:119–29. doi: 10.3109/07380570903329610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Utility of a brief screening tool to identify physicians in distress. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:421–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Shanafelt T. Ability of a 9-item well-being index to identify distress and stratify quality of life in US workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58:810–7. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valid and reliable survey instruments to measure burnout, well-being, and other work-related dimensions. Washington (DC): National Academy of Medicine; [accessed 2020 Jan. 6]. Available https://nam.edu/valid-reliable-survey-instruments-measure-burnout-well-work-related-dimensions/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyrbye LN, Johnson PO, Johnson LM, et al. Efficacy of the Well-Being Index to identify distress and well-being in U.S. nurses. Nurs Res. 2018;67:447–55. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dyrbye LN, Johnson PO, Johnson LM, et al. Efficacy of the Well-Being Index to identify distress and stratify well-being in nurse practitioners and physician assistants. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2019;31:403–12. doi: 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spreitzer GM. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manage J. 1995;38:1442–65. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:836–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham J, Ramirez AJ. Mental health of hospital consultants. J Psychosom Res. 1997;43:227–31. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams ES, Konrad TR, Linzer M, et al. SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. Physician, practice, and patient characteristics related to primary care physician physical and mental health: results from the Physician Worklife Study. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:121–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shanafelt TD. Enhancing meaning in work: a prescription for preventing physician burnout and promoting patient-centered care. JAMA. 2009;302:1338–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388:2272–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1105–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:195–205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Gill PR, et al. Effect of a professional coaching intervention on the well-being and distress of physicians: a pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1406–14. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rubin B, Goldfarb R, Satale D, et al. Burnout and distress among physicians in a cardiovascular centre of a quaternary hospital network: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:10–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin B, Goldfarb R, Satale D, et al. Burnout and distress among nurses in a cardiovascular centre of a quaternary hospital network: a cross-sectional survey. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:19–28. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.