Abstract

Across the USA, morbidity and mortality from substance use are rising as reflected by increases in acute care hospitalisations for substance use complications and substance-related deaths. Patients with substance use disorders (SUD) have long and costly hospitalisations and higher readmission rates compared to those without SUD. Hospitalisation presents an opportunity to diagnose and treat individuals with SUD and connect them to ongoing care. However, SUD care often remains unaddressed by hospital providers due to lack of a systems approach and addiction medicine knowledge, and is compounded by stigma. We present a blueprint to launching an interprofessional inpatient addiction care team embedded in the hospital medicine division of an urban, safety-net integrated health system. We describe key factors for successful implementation including: (1) demonstrating the scope and impact of SUD in our health system via a needs assessment; (2) aligning improvement areas with health system leadership priorities; (3) involving executive leadership to create goal and initiative alignment; and (4) obtaining seed funding for a pilot programme from our Medicaid health plan partner. We also present challenges and lessons learnt.

Keywords: patient-centred care, hospital medicine, healthcare quality improvement, PDSA, quality improvement

Introduction

In 2018, 20.3 million people in the USA had an active alcohol or drug use disorder.1 Opioid overdose deaths have reached epidemic proportions, with alcohol and stimulant-related deaths also rising.2 3 Simultaneously, between 2009 and 2014 hospitalisations for people with substance use disorders (SUD) nearly doubled.4 These hospitalisations are long, costly and associated with high rates of readmission and self-discharge (discharge against medical advice).5 6

Hospitalisation is an opportunity to offer SUD care to patients and connect them to ongoing services, since many are motivated to reduce substance use during hospitalisation.7 Offering and initiating addiction treatment is associated with decreased substance use and readmission rates, and increased linkage to postdischarge care and retention in SUD treatment.8–10 Providing addiction treatment to inpatients also improves patient and provider experiences.11

In this landscape, a variety of acute care SUD models have been developed, including addiction medicine consult services (AMCS). However, funding them is challenging and only a few AMCS are embedded in safety-net health systems.12 We present our approach to launching the Addiction Care Team (ACT), an interprofessional AMCS, in an urban, integrated safety-net health system. We share key factors for successful implementation, the current state of addiction care in our hospital, and ongoing challenges.

Setting

San Francisco General Hospital (SFGH) is a public hospital and the only Level 1 Trauma Centre in City and County of San Francisco and northern San Mateo County. There are about 75 000 emergency department (ED) visits and 16 500 hospitalisations annually. SFGH has 284 inpatient beds, 58 ED beds and 24 hour psychiatric emergency services. The hospitalised population is 27% Latinx, 26% White, 22% African American/Black, 18% Asian or Pacific Islander and 7% other.

SFGH is part of the San Francisco Department of Public Health (DPH) within the San Francisco Health Network, the city’s integrated health system, which includes primary care, jail health, behavioural health and a skilled nursing facility.

Developing a plan

Preintervention addiction care

Several SUD resources existed prior to the ACT. These included hospital guidelines for alcohol and opioid withdrawal monitoring and management, naloxone coprescribing for overdose prevention, and protocols to initiate medications for addiction treatment (MAT), including naltrexone, methadone and buprenorphine. However, these practices were variably implemented and largely underutilised by providers.

One physician voluntarily staffed a pager to assist teams in initiating buprenorphine. The only funded programme was comprised of three DPH licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) who counselled hospitalised patients with tobacco or unhealthy alcohol use. LVNs offered nicotine replacement therapy and referral to the California Smokers’ Hotline and assessed those with unhealthy alcohol use for alcohol use disorder and naltrexone candidacy.

Because most efforts were unfunded, siloed and uncoordinated, many care gaps remained. These were especially apparent in care transitions (ie, psychosocial treatment referral and follow-up), MAT initiation and harm reduction counselling. These gaps contributed to high readmission rates among patients with SUD.

Identifying shared priorities

In September 2017, we launched a taskforce composed of stakeholders dedicated to improving health system addiction care. This workgroup included nurses, pharmacists, social workers, physicians and SUD community-based organisation representatives. Importantly, we also invited executive leadership from our integrated health network and the San Francisco Health Plan, a Medicaid managed care plan and the major Medicaid insurer for our health network patients.

Meeting monthly, the taskforce conducted a two-pronged needs assessment. First, we emailed an anonymised survey (online supplemental appendix 1) to hospital trainee, nurse, attending physician and social worker listservs. Using a Likert scale, we inquired about staff and provider satisfaction with inpatient SUD care, comfort delivering addiction care, and what features would be most important in an AMCS.

bmjoq-2020-001111supp001.pdf (63.2KB, pdf)

Second, we extracted electronic health record (EHR) data of hospitalisations between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2016. To identify substance use-related hospitalisations, we categorised hospitalisations into those with SUD International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 code(s) and those without one. We also compared demographic and psychosocial factors, and acute care utilisation between these groups.

The taskforce then matched SUD improvement areas with our health network’s priorities of equity, safety, quality, care experience, developing staff and providers, and financial stewardship. We also reviewed AMCS literature and interviewed existing service directors about the funding and composition of their consultation teams.7–9 12

Needs assessment results

Survey

Of the 128 respondents, 79% thought SFGH probably or definitely needed to transform its approach to SUD care and 89% thought an AMCS would be very or extremely useful for staff, providers and patients. Respondents thought it would be very important for an AMCS to provide assistance with: (1) SUD discharge planning and care transitions (84%); (2) cooccurring mental health disorder management (72%); (3) motivational interviewing and counselling services (69%); (4) MAT advice (62%); (5) staff and provider addiction education (56%); and (6) withdrawal management (52%).

EHR data

Among 12 580 adult acute care hospitalisations, 28% had SUD ICD 10 code(s) in the top 10 discharge diagnoses. Alcohol-, amphetamine-, opioid- and cocaine-related diagnoses were found in 54%, 27%, 26% and 23% of SUD-related hospitalisations, respectively (not mutually exclusive).

Primary insurance for SUD-related hospitalisations was 73% Medicaid, 16% Medicare, 5% private, 2% Medicare–Medicaid and 4% other and 43% were unassigned to primary care. Compared with those without SUD-related hospitalisations, those with were more likely to experience homelessness (42% vs 9%), mental illness (30% vs 17%), 30-day readmissions (16% vs 11%) and self-discharges (11% vs 2%).

Executing the plan

Obtaining executive sponsorship and funding

We presented needs assessment results and taskforce recommendations in a Lean A3 format, our health system’s preferred problem-solving process, to hospital, health network and health plan leadership in May 2018.13 The higher readmission rates among those with SUD-related hospitalisations alarmed executive leadership. In addition, the disproportionate rates of people experiencing homelessness and mental illness, as well as overrepresentation of people of colour (data not shown) highlighted inequities in our health system and tied to health system priorities of reducing inequities. Because our proposed AMCS aimed to improve care linkages and potentially reduce readmissions, and because meeting California’s Medicaid incentive programme metric of reducing 30-day readmissions as well as reducing inequities were organisational priorities, supporting an AMCS became a funding priority for executive leadership.

Our efforts coincided with the health plan’s Quality Improvement Programme to advance clinical quality and patient safety for people with SUD. As part of its response to the opioid overdose epidemic, the health plan sought to support local health systems to increase their capacity to initiate MAT. Using strategic reserve funds, the health plan awarded our health network a 3-year US$900 000 grant to pilot the ACT at SFGH.

Implementation

We designed the ACT based on available funding, needs assessment results and existing AMCS models. The ACT was rolled out in January 2019 in a stepwise fashion to pilot and improve workflows, build capacity, and develop collaborations with hospital services. The team consisted of a half-time attending, full-time patient navigator and a rotating addiction medicine fellow. The three alcohol and tobacco focused DPH LVNs were integrated into the ACT and onsite 7 days a week. All other ACT providers are onsite Monday–Friday. Fellows provide telephone support afterhours on weekdays and attendings cover weekends.

ACT attendings include addiction medicine board-certified and board-eligible providers.14 Providers were recruited from family medicine, internal medicine, toxicology, obstetrics and gynaecology, addiction psychiatry and adolescent medicine based on having addiction medicine board-certification or committing to obtaining it. Table 1 details ACT roles and responsibilities.

Table 1.

ACT Members, Roles and Responsibilities

| Team member | Needs addressed | Workflow | Responsibilities |

| LVN 2.9 FTE |

|

|

|

| Patient navigator 1.0 FTE |

|

|

|

| Fellow 0.75 FTE |

|

|

|

| Attending 0.5 FTE |

|

|

|

ACT, Addiction Care Team; FTE, full-time equivalent; LVN, licensed vocational nurse; SUD, substance use disorder.

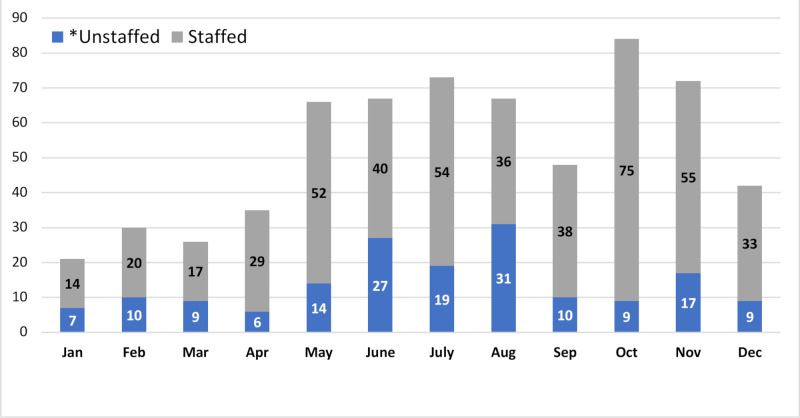

The ACT is unique in both responding to primary team consults and LVNs proactively seeing patients with unhealthy substance use. Like other AMCSs, our team has led system-wide addiction care improvements via interprofessional education, creating EHR SUD ordersets, and petitioning the hospital formulary committee to increase the availability of evidence-based addiction pharmacotherapies.12 In its first year of service, despite a staggered roll-out, the ACT experienced a rapid uptake with 631 consultation requests (figure 1) and more than 20 direct discharges to residential treatment programmes.

Figure 1.

ACT consultation requests, 1 January 2019–31 December 2019. *ACT was consulted for 631 hospitalisations during our first year. We staffed 73% of consults. Reasons consults went unstaffed include consultation question was answered via phone, ACT not yet available to requesting service or patient discharged prior to being seen.

Billing

The ACT bills using consultation codes under time-based or element-based documentation and recoups professional fees. As a county hospital in a Medicaid expansion state, most ACT patients are insured by a managed Medicaid plan and the hospital is reimbursed via capitated payments. Uninsured and undocumented patients may qualify for Healthy San Francisco, a programme for San Francisco residents financed by the city’s general fund which includes access to preventative, primary and hospital care within the city.

Challenges

In its first year, the ACT’s key challenge was expanding capacity to meet overwhelming service demand. More than a quarter of consults remained unstaffed, and we were unable to offer services to psychiatry and ED patients. We achieved our current capacity by augmenting health plan seed funding with additional time-limited grants and philanthropic support.

Although the service addresses core needs identified by our taskforce, financial sustainability remains uncertain. Billing revenue is severely inadequate to finance the ACT and this is an ongoing and growing concern in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. While EDs and hospitals reported decreased patient volumes, the ACT’s consult requests increased by over 30% (data not shown) when shelter-in-place orders were implemented in San Francisco on 17 March 2020, and we expect volume to only increase with a worsening addiction epidemic.15–18 Given growing demand for ACT services, future opportunities may involve consultations via telemedicine.

Finally, also due to financial limitations, the ACT is currently unable to support a dedicated addiction medicine mental health provider. Per needs assessment results, 30% of patients with SUD-related hospitalisations have a co-occurring mental health disorder and this is the second highest need identified by survey respondents. While a psychiatric consultation service exists, its bandwidth is limited to psychiatric emergencies.

We are currently completing a 3-year ACT pilot and evaluating impact to secure sustainable funding and continue improving care for hospitalised patients with SUD.

Lessons learned

A SUD taskforce led to a unified, system-based approach to addressing SUD during hospitalisation via the ACT at SFGH. Key contributors to successfully launching the ACT were: (1) demonstrating the scope and impact of SUD in our health system through a needs assessment that incorporated EHR data and staff and provider perspectives; (2) aligning improvement areas identified by our needs assessment with health network priorities; (3) early involvement of executive leadership, which created goal and payer initiative alignment; and (4) obtaining seed funding from our health plan to support the ACT.

This perspective presents a blueprint for health systems to launch their own AMCS. As the SUD epidemic continues taking its toll on our society, exacerbating existing inequities, and the isolation and trauma caused by COVID-19 continues, complications of substance use rise. It is more important than ever for health systems to provide high-quality, equitable and evidence-based care for people with SUD by expanding the number of AMCS.

Footnotes

Twitter: @MarleneMartinMD

Funding: Publication made possible with support from the UCSF Open Access Publishing Fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 national survey on drug use and health (HHS publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH series H-54). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2019. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillane S, Shiels MS, Best AF, et al. Trends in alcohol-induced deaths in the United States, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e1921451. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.21451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS data brief, no 356. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss AJ. Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits by State, 2009-2014. HCUP Statistical Brief #219. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2016. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owens PL. Inpatient Stays Involving Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2016. HCUP Statistical Brief #249, 2019. Available: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb249-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorder-Hospital-Stays-2016.pdf [PubMed]

- 6.Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addict Med 2012;6:50–6. 10.1097/ADM.0b013e318231de51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the improving addiction care team (impact) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med 2017;12:339–42. 10.12788/jhm.2736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, et al. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:909–16. 10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services - Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017;79:1–5. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebschutz JM, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1369–76. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Englander H, Collins D, Perry SP, et al. "We've Learned It's a Medical Illness, Not a Moral Choice": Qualitative Study of the Effects of a Multicomponent Addiction Intervention on Hospital Providers' Attitudes and Experiences. J Hosp Med 2018;13:752–8. 10.12788/jhm.2993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Priest KC, McCarty D. Role of the hospital in the 21st century opioid overdose epidemic: the addiction medicine consult service. J Addict Med 2019;13:104–12. 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shook J. Managing to learn: using the A3 management process to solve problems, gain agreement, mentor and lead. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addiction medicine: practice pathway. American Board of preventative medicine, 2020. Available: https://www.theabpm.org/become-certified/subspecialties/addiction-medicine

- 15.Wong LE, Hawkins JE, Langness S. Where are all the patients? addressing Covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. NEJM Catalyst: Innovations in Care Delivery 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16.55 percent fewer Americans sought hospital care in March-April due to COVID-19, driving a clinical and financial crisis in U.S. healthcare, 2020. Strata decision technology. Available: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/55-percent-fewer-americans-sought-hospital-care-in-march-april-due-to-covid-19-driving-a-clinical-and-financial-crisis-in-us-healthcare-301056570.html [Accessed May 14, 2020.].

- 17.Drug abuse warning network and COVID-19, 2020. Center for behavioral health statistics and quality. Substance abuse and mental health service administration. Available: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt32811/DAWN%20COVID%20Profile.pdf

- 18.Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2022942. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjoq-2020-001111supp001.pdf (63.2KB, pdf)