Abstract

Obesity is very common in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (IRDs), of which between 27% and 37% of patients have a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. In addition to further increasing the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) in this group of patients, obesity is associated with higher disease activity and a lower response to drug therapy. This case series showed that in those patients with rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis with a substantial weight loss of >10% of body mass, median Disease Activity Score 28 joints score decreased with 0.9. This reduction in disease activity resulted in an increase in the percentage of patients achieving remission from 6% to 63%. This reduction in disease activity was obtained without intensification of medical treatment in 87% of the patients. This case series supports the current evidence that weight reduction has positive effects on the course of the disease and thus also on the CVD risk profile in these patients. Therefore, weight loss can serve as a non-pharmacological treatment option in obese patients with IRDs.

Keywords: arthritis, psoriatic, rheumatoid, cardiovascular diseases

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Obesity is very common in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (IRDs), At the same time, it has been hypothesised that patients with obesity tend to have higher disease activity scores and lower response rates for rheumatic medication.

What does this study add?

Our data showed that in those patients with rheumatoid arthritis or psoriatic arthritis with a substantial weight loss of >10% of body mass, median Disease Activity Score 28 joints score decreased with 0.9. This reduction in disease activity was obtained without intensification of medical treatment in the majority of the patients.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

These findings reinforce the necessity to include non-pharmacological treatment options, including weight loss, as an integrated part of disease management in obese patients with IRDs.

Introduction

Overweight and obesity are recognised as epidemic by the WHO and they cause or exacerbate a large number of health problems, both independently and in association with other diseases.1 Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health. To date obesity, body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, has been proven to play an important role in developing cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), and it has been linked to many chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer and (inflammatory) rheumatic diseases.2 3

Obesity is also highly prevalent in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases (IRDs) (eg, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA)) compared with the general population (27%–37% vs 18%).4 Due to the inflammatory aspects of adipose tissue, it has been hypothesised that obesity could function as an independent risk factor for the development of IRDs.5–9

At the same time, it has been hypothesised that obesity could affect disease activity and treatment response in IRDs. This hypothesis is supported by a recent meta-analysis that showed that people with obesity tend to have higher disease activity scores and lower response rates for both traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs)) and biological drugs.10 Besides the effects of obesity on joint inflammation itself, it also contributes to increased cardiovascular mortality and morbidity among patients with RA and PsA compared with the general population.11 12 Both the systemic inflammation caused by IRD and the increased prevalence of traditional CVD risk factors in IRD patients contribute to this greater risk to develop CVD.13 Weight loss might reduce the elevated risk of CVD by reduction of joint and systemic inflammation.

Following this train of thoughts, a reduction of weight could lead to better health outcomes. Therefore, the rheumatology outpatient clinic of Bernhoven in the Netherlands decided to pay more attention to improve lifestyle factors. This viewpoint describes a case series of patients with RA and PsA followed at this outpatient clinic, who lost weight. Subsequently, the results of this case series are compared with the current evidence about the effect of weight loss on disease activity. This results in a call to further optimise rheumatic disease management by include optimisation of lifestyle factors as a vital component in the management of articular and extra-articular manifestations of rheumatic diseases.

Methods

Study design and population

We performed a retrospective medical chart review of all patients diagnosed with either RA or PsA, visiting the outpatient clinic of the rheumatology department in Bernhoven, a hospital in the south of the Netherlands, between March 2019 and July 2019 to identify patients who had undergone significant weight loss. At that moment, the outpatient clinic treated 1059 patients with RA and 379 patients with PsA. Patients were eligible as case in this study if they met the following five criteria: (1) age above 18 years; (2) classified with RA according to ACR/EULAR 2010 RA classification criteria14 or with (PsA) according to the 2006 CASPAR criteria15; (3) had at least two weight measurements which observed an intentional weight loss ≥10% of total body mass; (4) highest weight measurement corresponded with a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2; (5) had at least two disease activity measurements, of which at least one was obtained before and one after weight loss.

Data collection and analyses

Patient data were collected through a retrospective review of the electronic medical records. Data on demographic (gender, date of birth) as well as disease-related characteristics (date of diagnosis) were collected. Body weight (in kilogram) and height (in metres) were also collected to calculate BMI. Body weight was measured by the rheumatologist or specialised rheumatology nurse in each patient at least annually at their visit at the outpatient clinic by calibrated scales. BMI before weight loss was identified for each patient at the last weight measurement prior to the start of weight loss. To calculate BMI after weight loss, the most recent weight measurement after weight loss was used. It was recorded whether the weight loss was due to a bariatric surgical procedure.

The Disease Activity Score 28 joints (DAS28) was used as a measure of disease activity (score between 0 and 10; higher score indicated higher disease activity).16 To study disease activity before weight loss, the DAS28 score prior to weight loss was identified. If patients weight had been stable (a fluctuation ≤2 kg) before start of follow-up, we calculated the average DAS28 during the stable period (allowing for an 1-year interval). To study disease activity after weight loss, the DAS28 score matching the most recent weight measurement was identified. If the patient had a stable (low) weight for a longer period, the average DAS28 for the period was calculated. In addition, disease activity status of patients before and after weight loss was categorised based on the DAS28 in four categories; remission (DAS28<2.6), low disease activity (DAS28≥2.6 and <3.2), moderate disease activity (DAS28≥3.2 and <5.1) and high disease activity (DAS28≥5.1).

For each patient, treatment intensity was categorised and identified before and after weight loss: (1) no antirheumatic medication; (2) csDMARD monotherapy; (3) csDMARD combination therapy; (4) biological monotherapy; (5) csDMARD biological combination therapy; (6) corticosteroid treatment. After weight loss, patients were classified in increased, stable or decreased treatment intensity based on changes in dose and in rheumatic medication category. If changes were made because of side effects, for instance a change to another treatment within the same treatment category or lowering of the dose, these were scored as stable treatment. The temporary use or increase of glucocorticoid therapy was classified as intensification of treatment.

Data were analysed using SPSS, V.25.0. Demographic and disease-related characteristics were presented as mean with SD or median with IQRs for continuous variables or the number (n) with percentages (%) for categorical variables. No statistical testing or subgroup analyses were performed due to the number of cases.

Results

Patient characteristics

We identified 16 patients who had a BMI>30 kg/m2 with at least 10% weight loss and adequate data for analysis. Ten patients (62%) were diagnosed with RA and six (38%) were diagnosed with PsA. The mean age of patients at start of weight loss was 54±11 years and 94% was women. Data related to patient characteristics at the start of the follow-up, weight loss, disease activity and rheumatic medication use were described in table 1.

Table 1.

Description of cases characteristics

| Anthropometrics | N=16 |

| Mean age, years, mean (SD) | 54 (11) |

| Female, % | 94 |

| Disease-related factors | |

| Diagnosis | |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis, % | 62 |

| Psoriatic Arthritis, % | 38 |

| DAS28 before weight loss, median (IQR) | 3.42 (2.94–4.30) |

| DAS28 after weight loss, median (IQR) | 2.48 (2.14–3.02) |

| Weight loss | |

| Method of weight loss | |

| Non-surgical, % | 75 |

| Gastric bypass surgery, % | 25 |

| BMI before weight loss, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 36 (35–42) |

| BMI after weight loss, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 28 (27–32) |

| Weight loss in kg, median (IQR) | 23 (13–29) |

| Rheumatic medication use | |

| csDMARD monotherapy, % | 50 |

| csDMARD combination therapy, % | 13 |

| csDMARD and biological combination therapy, % | 25 |

| Biological monotherapy, % | 6 |

| No rheumatic medication, % | 6 |

BMI, body mass index; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; DAS28, Disease Activity Score 28 joints.

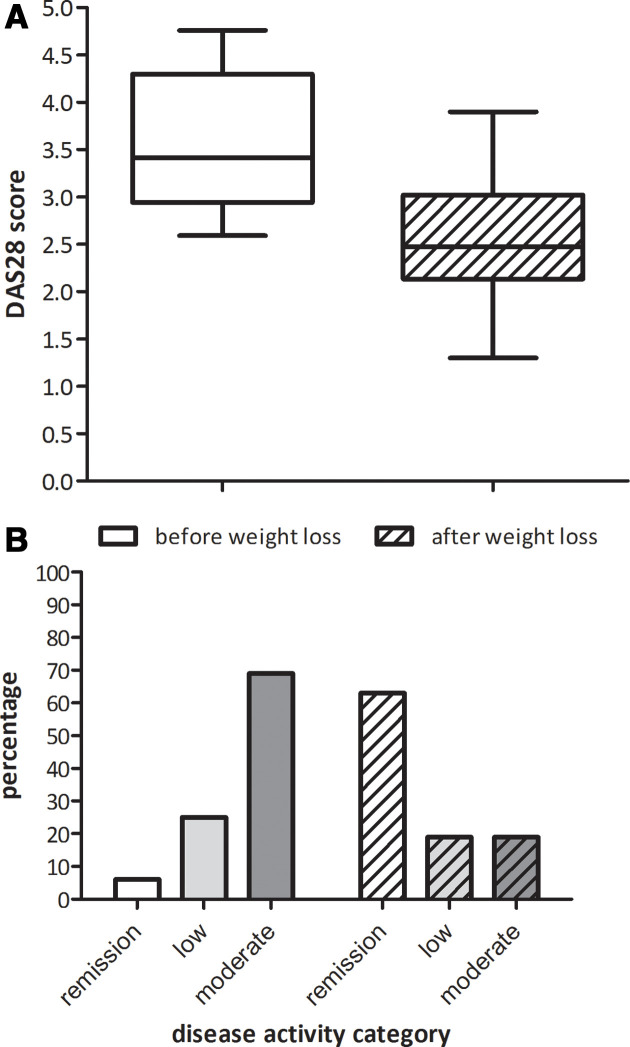

Weight loss and disease activity

The median starting BMI was 36 kg/m2 (IQR 35–42). During a median period of 1.9 years (IQR 1.3–2.5) median weight loss was 23% of the initial body weight (IQR 14–25). The median DAS28 score before weight loss was 3.42 (IQR 2.94–4.30). During a median follow-up of 1.9 years (IQR 1.3–2.5) DAS28 score decreased to 2.48 (IQR 2.12–3.02) (figure 1A). When categorising the DAS28 into disease activity level, the percentage of patients in remission increased from 6% to 63%, while the percentage of patients with moderate disease activity decreased from 69% to 19% (figure 1B). There were no patients with a high disease activity before and after weight loss.

Figure 1.

Effect of weight loss on disease activity. DAS28, Disease Activity Score 28 joints.

Weight loss and rheumatic medication use

Initially eight (50%) of the patients were treated with csDMARD monotherapy, two (13%) received csDMARD combination therapy, one (6%) received biological monotherapy and four (25%) received csDMARD biological combination therapy. One patient (6%) did not receive antirheumatic medication.

During weight loss the medication was reduced in five patients (31%) and intensified in two patients (13%). In the majority of the patients (n=9, 56%) treatment intensity did not change during their weight loss. Both patients whose treatment was intensified, were temporally treated with glucocorticoid.

Discussion

Our data showed that in those patients with RA or PsA with a substantial weight loss of >10% of body mass, median DAS28 score decreased with 0.9. The reduction in disease activity resulted in an increase from 6% to 63% in the number of the patients achieving remission. This was achieved without an intensification of treatment in 87% of the patients.

This study contributes to the growing evidence that lifestyle factors may influence not only the risk to develop CVD or other comorbidities, but also the disease course and the response to treatments. To date very few studies have prospectively researched the influence of weight loss on disease course in IRDs. Our daily practice study showed comparable results of improvement of disease activity in patient with PsA or RA as in the studies of Klingberg et al, Sparks et al and Krebs et al investigating weight loss after interventions such as a very low energy diet or bariatric surgery.17–19 At the same time, our results and Sparks et al showed that a reduction in disease activity could be achieved without intensifying antirheumatic medication.18

In our view, the following limitations of our study are important to mention: relative small number of patients and the retrospective collected data. In addition, not all patients with a substantial weight loss might have been included as we were dependent on the spontaneous registration by the rheumatologists. However, our observation, together with existing data, gives a strong signal to pay attention to this lifestyle factor in daily clinical practice.

These findings reinforce the necessity to include non-pharmacological treatment options as an integrated part of disease management. However, the current management of IRD is based on several principles of which the main focus is pharmacological treatment.20–23 Non-pharmacological treatment options, such as a healthy diet, smoking cessation, physical activity, can help to reduce the burden of disease and should be recommended as a vital component in the management of IRDs. Giving non-pharmacological treatment options a more prominent role in the current treatment recommendations for RA and PsA (and other rheumatic diseases) will help implement these strategies into daily clinical practice. This could be a first step to implement lifestyle factors as a part of rheumatic diseases management.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the development of this manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee Arnhem-Nijmegen and it was judged that the study did not fall within the scope of the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (number 2020-6406). Collected data are anonymised and results are not traceable to individual cases.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Controlling the global obesity epidemic, 2003. Available: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en/ [Accessed 21 Aug 2020].

- 2.Kopelman P. Health risks associated with overweight and obesity. Obes Rev 2007;8:13–17. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gremese E, Tolusso B, Gigante MR, et al. Obesity as a risk and severity factor in rheumatic diseases (autoimmune chronic inflammatory diseases). Front Immunol 2014;5:576. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhole VM, Choi HK, Burns LC, et al. Differences in body mass index among individuals with PSA, psoriasis, RA and the general population. Rheumatology 2012;51:552–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francisco V, Pino J, Campos-Cabaleiro V, et al. Obesity, fat mass and immune system: role for leptin. Front Physiol 2018;9:640. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maglio C, Zhang Y, Peltonen M, et al. Bariatric surgery and the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis - a Swedish Obese Subjects study. Rheumatology 2020;59:303–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu B, Hiraki LT, Sparks JA, et al. Being overweight or obese and risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis among women: a prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1914–22. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Hair MJH, Landewé RBM, van de Sande MGH, et al. Smoking and overweight determine the likelihood of developing rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1654–8. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowson CS, Matteson EL, Davis JM, et al. Contribution of obesity to the rise in incidence of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2013;65:71–7. 10.1002/acr.21660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lupoli R, Pizzicato P, Scalera A, et al. Impact of body weight on the achievement of minimal disease activity in patients with rheumatic diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:297. 10.1186/s13075-016-1194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aviña-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, et al. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1690–7. 10.1002/art.24092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russolillo A, Iervolino S, Peluso R, et al. Obesity and psoriatic arthritis: from pathogenesis to clinical outcome and management. Rheumatology 2013;52:62–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowson CS, Rollefstad S, Ikdahl E, et al. Impact of risk factors associated with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:48–54. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay J, Upchurch KS. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology 2012;51:vi5–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, et al. Classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2665–73. 10.1002/art.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Riel PL. The development of the disease activity score (DAS) and the disease activity score using 28 joint counts (DAS28). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014;32:65–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klingberg E, Bilberg A, Björkman S, et al. Weight loss improves disease activity in patients with psoriatic arthritis and obesity: an interventional study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:17. 10.1186/s13075-019-1810-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sparks JA, Halperin F, Karlson JC, et al. Impact of bariatric surgery on patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:1619–26. 10.1002/acr.22629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kreps DJ, Halperin F, Desai SP, et al. Association of weight loss with improved disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis using electronic medical record data. Int J Clin Rheumtol 2018;13:1–10. 10.4172/1758-4272.1000154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:685–99. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL, et al. 2015 American College of rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2016;68:1–25. 10.1002/acr.22783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogdie A, Coates LC, Gladman DD. Treatment guidelines in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology 2020;59:i37–46. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Combe B, Landewe R, Daien CI, et al. 2016 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:948–59. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]