Abstract

Schistosoma sinensium belongs to the Asian Schistosoma and is transmitted by freshwater snails of the genus Tricula. Rodents are known definitive hosts of S. sinensium. In 2016, suspected schistosome eggs were found in the feces of the northern tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) in a field in Lufeng County (latitude, 25°04′50″ N; longitude, 102°19′30″ E; altitude 1820 m), Yunnan Province, China. Morphological analysis suggested that the schistosome was S. sinensium. 18S, 12S and CO1 genes sequencing and phylogenetic analysis showed that this species had the highest similarity to and occupied the same evolutionary branch as S. sinensium from Mianzhu, Sichuan, China. Meanwhile, based on 16S and 28S rDNA sequencing and morphological identification, the snail intermediate host was identified as a species of Tricula, and was found in irrigation channels. Phylogeny indicated that Tricula sp. LF was a sister taxon to T. bambooensis, T. ludongbini. The S. sinensium was able to experimentally infect the captive-bred Tupaia belangeri, and Schistosoma eggs were recovered from all Tupaia belangeri exposed. In this study, we report the infection of Tupaia belangeri and Tricula sp. LF with S. sinensium in Lufeng, Yunnan, southwest China. These findings may improve our understanding of the host range, evolution, distribution, and phylogenetic position of S. sinensium.

Keywords: Schistosoma sinensium, Tupaia belangeri, Tricula sp. LF

Highlights

-

•

First report Tupaia belangeri and Tricula. sp. LF act as hosts of Schistosoma sinensium in nature.

-

•

The schistosome is highly similar to S. sinensium from Mianzhu, Sichuan, China, by morphology and genes analyses.

-

•

The snail intermediate host, Tricula. sp. LF, was also found and identified based on morphology and genes.

-

•

Geographic location of occurrence is Lufeng, Yunnan, China (25°04'50" N; 102°19'30" E; altitude, 1820 m).

1. Introduction

Schistosoma Weinland, 1858, is a genus of trematodes (blood flukes) that causes schistosomiasis in mammals, including humans, and is prevalent in tropical and subtropical areas. Schistosomiasis is a serious and debilitating disease affecting humans and animals and is considered by the World Health Organization as the second most socioeconomically important parasitic disease after malaria. Over 20 schistosome species associated with human or animal diseases have been identified to date (Attwood et al., 2007). The host of an individual schistosome is restricted, although some schistosomes have a wide range of hosts including humans and some livestock (Attwood et al., 2002a).

Schistosoma sinensium Bao, 1958, was first isolated from an unidentified snail in Mianzhu County, Sichuan Province, China. This schistosome species was described on the basis of the morphological analysis of adult worms and eggs (Pao, 1959), and the snail species was identified as Tricula hortensis by Attwood (Attwood et al., 2003). Schistosoma sinensium is found throughout southern China, southeast Asia, and northern India. Molecular analysis showed that S. sinensium belongs to the Asian Schistosoma and is a sister clade to S. japonicum, although egg morphology was similar to that of Schistosoma mansoni, with a lateral spine (Agatsuma et al., 2001; Lawton et al., 2011). Schistosoma sinensium has been located in Weishan, Yunnan Province, and Napo, Guangxi Province of China (Hu et al., 2003; Yang et al., 1995). Kruatrachue et al. (1983) isolated S. sinensium from the snail Tricula bollingi in northwest Thailand. Field rodents and laboratory rabbits are definitive hosts of S. sinensium.

Triculine snails (Pomatiopsidae Stimpson, 1865: Triculinae Annandale, 1924) are found in freshwater habitats in southern China and southeast Asia. The Triculinae show high biodiversity and major adaptive radiation in Yunnan/Sichuan Province, southwest China, the lower Mekong Basin, and Hunan Province, China (Attwood et al., 2002a). Tricula bollingi (Kruatrachue et al., 1983), and T. hortensis (Attwood et al., 2003) were intermediate hosts of S. sinensium.

The northern tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) is a small mammals closely related to primates and highly similar to humans in terms of anatomy and physiology, neural development, and responses to viral infection and psychological stress (Xu et al., 2013). These animals live in tropical and subtropical jungles and are widely distributed in South and Southeast Asia and Southwest China. Tree shrews have been proposed as experimental models for biomedical research (Xu et al., 2012).

In August 2016, schistosome eggs were found in the feces of a female Tupaia belangeri in Lufeng County, Yunnan Province, China. Egg morphology was similar to that of Schistosoma mansoni, with a long lateral spine. Subsequently, two other cases were observed. Adult worms were recovered from the veins of a deceased Tupaia belangeri that had shed eggs. The worms were identified as S. sinensium based on morphology and 18S, 12S and CO1 genes sequencing. The snail intermediate host, Tricula sp., was found in the same geographic location, and named Tricula sp. LF (LF is the abbreviation of Lufeng). Subsequently, infection experiments were performed to verify that the snail and Tupaia belangeri can act as hosts of S. sinensium. This study reports that Tupaia belangeri and a novel Tricula sp. LF were infected with S. sinensium in nature. These findings help understand the evolution and distribution pattern of S. sinensium.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Animal Care and Welfare Committee of the Institute of Medical Biology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College. All procedures were performed according to ethical standards and practices.

2.2. Geographic location and ecological environment

Tupaia belangeri specimens were collected at the outskirts of Qinfengying Town, Lufeng County, Yunnan Province, China (latitude, 25°04′50″ N; longitude, 102°19′30″ E; altitude, 1820 m). Freshwater snails resembling Pomatiopsidae were collected from flowing streams in irrigation canals in the same area where the animals were trapped. The water was clear, and the bottom sediment consisted of silt. This snail species lives mainly on stones, sediments, and floating leaves and branches of decaying plants. Other snail species of genera Gyraulus and Radix were also found in the same ecological environment.

2.3. Morphological and molecular identification of schistosomes

Infected animals were euthanized with excess sodium pentobarbital and adult worms recovered by perfusion. Eggs, miracidia, and cercariae were observed under a light microscope. A total of 100 mature eggs were measured (Nikon 50i, NIKON, Tokyo, Japan). Data are presented as ranges. Measurements of miracidia, cercariae, and worms were made using a stereoscope (Nikon SMZ 1500, NIKON, Tokyo, Japan).

Fresh fecal samples were sieved and washed with saline, and schistosome eggs were allowed to hatch in freshwater. Miracidia were collected using a pipette. Total DNA was extracted from 70 miracidia using a PureLink® Genomic DNA Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Primers were designed using Primer Premier version 6.0 (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/primerdesign/index.html) based on the S. sinensium 18S small-subunit ribosomal RNA gene (GenBank Accession No. AY157225.1), 12S and CO1 primers quoted in Bowles (Bowles et al., 1993), (Table 1), and PCR was carried out using a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Amplification products were sequenced and compared with GenBank sequences using BLAST. Phylogenetic trees were constructed to analyze evolutionary relationships. Highly similar sequences were selected for multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the maximum likelihood method (ML) based on the Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura, 1980), in addition, the evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum parsimony method (MP) in MEGA version 7.0.14 (Kumar et al., 2016). The sequences used in the present study were all from Genbank and selected after sequence alignment.

Table 1.

Sequence analyses of Schistosoma sinensium and Tricula sp. LF.

| Species | Locus | Primer sequence | Authors | length(bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schistosoma sinensium | 18S | 5′- ACAGGTGTCGATGGGTTAATGA -3′ 5′- GTAAAAACTGGCACCGCACC -3′ |

798 | |

| 12S | 5′-TTTGTCCACAGTTATAACTGAAAGG -3′ 5′- GATTCTTCAAGCACTACCATGTTACGAC -3′ |

Bowles et al. (1993) | 331 | |

| CO1 | 5′-TTTTTTGGGCATCCTGAGGTTTAT-3′ 5′-TAAAGAAAGAACATAATGAAAATG-3 |

Bowles et al. (1993) | 402 | |

| Tricula sp. LF | 16S | 5′- CGCCTGTTTATCAAAAACAT -3′ 5′- CCGGTCTGAACTCAGATCACGT -3′ |

Palumbi. (1996) | 516 |

| 28S | 5′-GTTAGACTCCTTGGTCCGTG-3′ 5′- ACCTCAGATCGGACGAGATTAC-3′ |

Wade and Mordan. (2000) | 764 |

2.4. Morphological and molecular identification of snails

The morphology of 100 Tricula sp. were analyzed using a stereoscope (Nikon SMZ 1500, NIKON, Tokyo, Japan). Radular preparations were done. Counts of radular cusps were determined from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images (HITACHI SU8100, Japan). These morphological characteristics were compared with those of Tricula bambooensis and T. ludongbini.

The snails were gently crushed, and the body were separated from the shell. Total genomic DNA was extracted using a Genomic DNA Mini Kit following the manufacturer's instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PCR primers were designed by Palumbi (1996) and Wade and Mordan (2000) (Table 1), and PCR was carried out using a thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Amplification products were sequenced, and the results were analyzed by SnapGene Viewer software and aligned by BLAST. Sequences with high similarity were selected for multiple sequence alignment using ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the maximum likelihood method based on the Kimura 2-parameter model (Kimura, 1980). and the evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum parsimony method in MEGA version 7.0.14 (Kumar et al., 2016).

2.5. Parasite infection experiment

Individual snails were exposed to 5–10 miracidia hatched from eggs of infected tree shrew. Five 5–10-month-old schistosome-free female tree shrews were each infected with approximately 150 cercariae shed by laboratory-reared snails following the protocol described by Greer et al. (1989).

3. Results

3.1. Morphology of schistosomes

Fig. 1 shows the gross appearance of the egg, miracidium, cercaria, and adult.

Fig. 1.

Morphology of S. sinensium at different life cycle stages. Miracidia and cercariae were stained with iodine. A. Egg. B. Miracidium. C. Cercaria. D. Male and female adult worms.

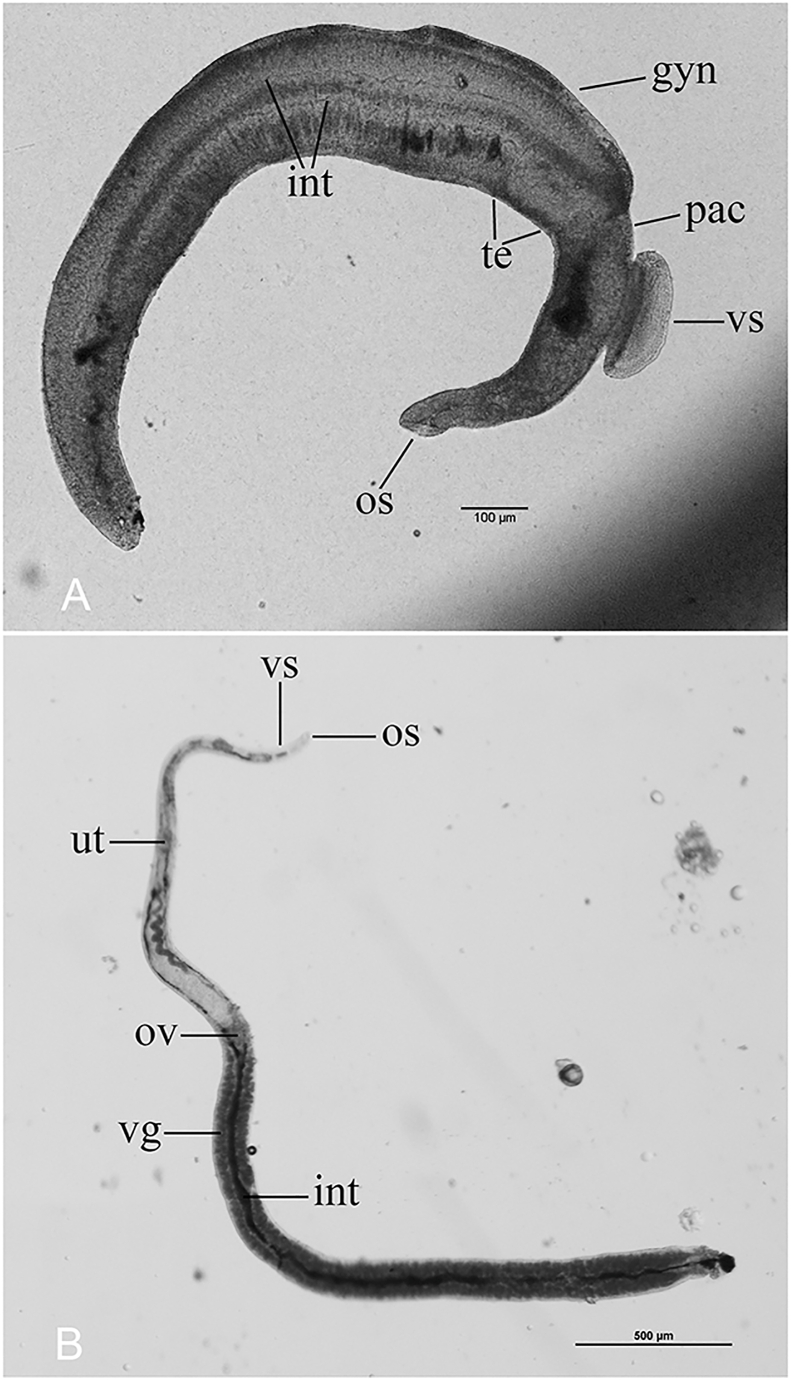

3.1.1. Male (N = 4) (Fig. 2A)

Fig. 2.

Enlarged worm picture. A. Male, showing oral sucker (os), ventral sucker (vs), constriction (pac), testes (te), gut caeca (int) and gynecophoral canal (gyn). B. Female, showing oral sucker (os), ventral sucker (vs), utero (ut), ovary(ov), vitellarium (vg) and gut caeca (int).

In this study, the average length of the male worm after 10 weeks was 3113 μm, ranging from 2590–3680 μm, the maximum body width of 218 μm, this is similar the 3200–3650 μm reported by Bao (Pao, 1959). Males appeared to have a smooth tegument, lacked tubercles or spines. The diameters of the oral and ventral suckers were 73–90 μm, and 147–248 μm respectively. The testes were 8 in number, and it were often found to overlap to some degree. The intestinal bifurcation in our isolate occurred just anterior to the ventral sucker, then reunite near the end of the worm. The constriction just posterior to the ventral sucker was most pronounced and similar to Attwood et al. (2002b).

3.1.2. Female (N = 3) (Fig. 2B)

The average length of the female worm after 10 weeks was 3787 μm, ranging from 3320–4170 μm, the mean maximum body width of 112 μm, similar to that recorded by Attwood et al. (2002b). The diameters of the oral and ventral suckers were 21–23 μm, and 43–46 μm respectively. Tegument smooth, lacking tubercles or spines. In worm, the posterior extremity was broader. The ovary was located in the front 1/3 of the worm. The vitellarium accounts for a large proportion, extending from behind the ovary to the posterior end of the worm. The intestines with obvious black substance bifurcated in the ventral sucker, converged behind the ovary.

3.1.3. Egg (N = 100) (Fig. 1A)

Eggs were elongated-oval and presented a lateral spine, with a length of 85.12–117.61 μm, width of 34.21–53.22 μm, and lateral spine length of 15.08–26.02 μm, which agree with previous analyses (Greer et al., 1989; Pao, 1959).

3.1.4. Miracidia (N = 5) (Fig. 1B)

The size of living miracidia varies greatly. The front has a conical protuberance. The body surface was covered with abundant cilia. There are two glandular cells in front of miracidia.

3.1.5. Cercaria (N = 5) (Fig. 1C)

The average body length is 160 μm, width is 66 μm, tail length is 140 μm. Cercariae have eight flame cells and rest on the water surface, these morphology and features are similar to those recorded by Bao (1959) and Attwood et al. (2002b).

3.2. Schistosome phylogeny

18S (Fig. 3A), CO1 (Fig. 3B) and 12S (Fig. 3C) gene sequencing results revealed a high degree of similarity (>99%) with the target sequence. Phylogenetic analysis showed that our sample was similar to another Chinese strain of S. sinensium. Two specimens of S. sinensium form a clade to the exclusion of all other species. Furthermore, it is a sister group to another Asian schistosome species, and is related to Schistosoma mansoni, S. nasale, S. incognitum, S. spindale, and S. indicum. Better concordance was observed between the phylogenies estimated by the two methods for the 18S, CO1 and 12S loci (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses of the present Schistosoma sinensium (♦) by the maximum likelihood method (ML) and maximum parsimony method (MP). Phylogenetic tree depicting relationships among Schistosoma species inferred from:

A. 18S nucleotide data analyses using ML (Ai) and MP (Aii).

[Schistosoma malayensis AY157227.1, Schistosoma mekongi AY157228.1, Schistosoma sinensium AY157225.1, Schistosoma indicum AY157231.1 and Schistosoma japonicum AY157226.1 were cited from Lockyer et al. (2003); Schistosoma incognitum JQ408706.1 was cited from Webster and Littlewood (2012); Schistosoma.spindale Z11979.1 was cited from Johnston et al. (1993)].

B. CO1 nucleotide data analyses using ML (Bi) and MP (Bii).

[Schistosoma malayensis AY157198.1, Schistosoma mekongi AY157199.1, Schistosoma sinensium AY157197.1 and Schistosoma incognitum AY157201.1 were cited from Lockyer et al. (2003); Schistosoma indicum NC_047240.1 was cited from Jones et al. (2020); Schistosoma nasale KR607232.1 was cited from Devkota et al. (2015)].

C.12S nucleotide data analyses using ML (Ci) and MP (Cii).

[Schistosoma mekongi AF217449.1 was cited from Le et al. (2000); Schistosoma sinensium AF465918.1 and Schistosoma ovuncatum AF465917.1 were cited from Attwood et al. (2002a); Schistosoma incognitum EF534279.1 was cited from Attwood et al. (2007); Schistosoma nasale KR607261.1 was cited from Devkota et al. (2015); Schistosoma mansoni MN593407.1 was cited from Catalano et al. (2020); Schistosoma indicum NC_047240.1 and Schistosoma spindale MN637820.1 were cited from Jones et al. (2020)].

Other sequences were from GenBank.

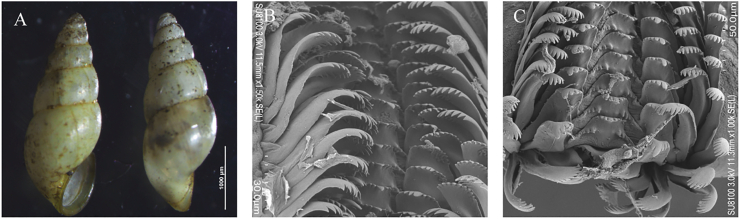

3.3. Snail morphology

The snails were 2.99–4.27 mm in height and 1.18–1.66 mm in width, with six slightly convex whorls, and ovate-turreted, glassy shells (when clean) with a smooth surface. The sutures were deep. The peristome was complete and had an oval aperture (Fig. 4A). The radular formula was: (Fig. 4B and C). Shell size and shape, and radular formula were slightly different from those of T. bambooensis and T. ludongbini (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Shell morphology of Tricula sp. LF. A. Shape. B–C. Scanning electron micrograph of the radula.

Table 2.

Geographical location and morphological analyses of Tricula sp. LF, T. bambooensis, and T. ludongbini.

| Tricula sp. LF | Tricula bambooensis (Davis et al., 1986) | Tricula ludongbini (Davis et al., 1986) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geographical position | 25°04′50″ N, 102°19′30″ E | 25°06′N, 99°45′ E | 25°06′N, 99°45′ E |

| Whorls | 6 | 6 | 5.5–6 |

| Shell length (mm) | 2.99-4.27 | 3.48-4.00 | 3.08-3.68 |

| Shell width (mm) | 1.18-1.66 | 1.64-1.80 | 1.48-1.72 |

| Radular teeth formulae | |||

| Shell shape and appearance | Ovate-turreted; Glassy |

Ovate-conical or ovate-turreted; Glassy |

Ovate-conical; Chalky |

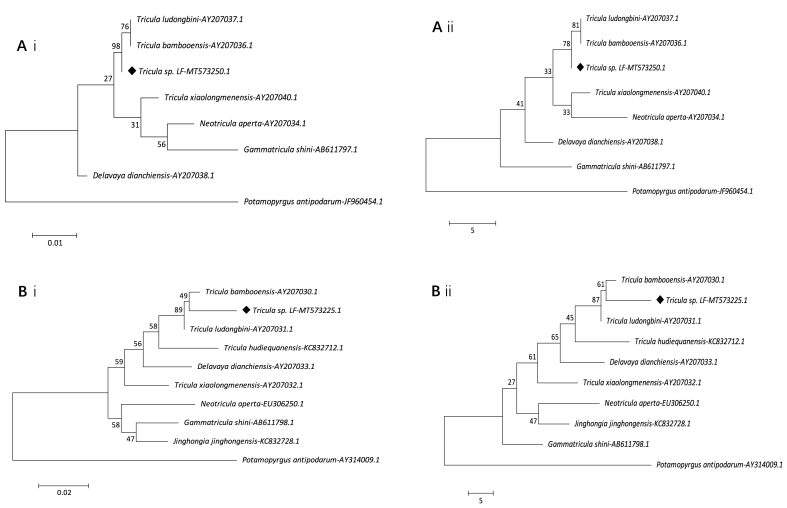

3.4. Snail phylogeny

The analysis of 16S (516bp) and 28S (764bp) gene sequences revealed a high degree of similarity (>90%) with other triculine snails. The obtained sequences were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MT573225 and MT573250. A phylogenetic tree was constructed and showed that Tricula sp. LF formed a clade with T. bambooensis and T. ludongbini (Fig. 5). Both results of 28S (Figs. 5A) and 16S (Fig. 5B) data were consistent by using the maximum likelihood and maximum parsimony methods. The same basic topology were obtained by using two methods.

Fig. 5.

Molecular phylogenetic analyses of the Tricula sp. LF (♦) by the maximum likelihood method (ML) and maximum parsimony method (MP). Phylogenetic tree depicting relationships among Tricula species inferred from:

A. 28S nucleotide data analyses using ML (Ai) and MP (Aii).

[Tricula ludongbini AY207037.1, Tricula bambooensis AY207036.1, Tricula xiaolongmenensis AY207040.1, Neotricula aperta AY207034.1 and Delavaya dianchiensis AY207038.1 were cited from Attwood et al. (2004); Gammatricula shini AB611797.1 was cited from Kameda and Kato (2011)].

Outgroup taxon Potamopyrgus antipodarum-JF960454.1.

B. 16S nucleotide data analyses using ML (Bi) and MP (Bii).

[Tricula ludongbini AY207031.1, Tricula bambooensis AY207030.1, Delavaya dianchiensis AY207033.1 and Tricula xiaolongmenensis AY207032.1 were cited from Attwood et al. (2004); Tricula hudiequanensis KC832712.1 and Jinghongia jinghongensis KC832728.1 were cited from Liu et al. (2014); Neotricula aperta EU306250.1 was cited from Attwood et al. (2008); Gammatricula shini AB611798.1 was cited from Kameda and Kato (2011)].

Outgroup taxon Potamopyrgus antipodarum-AY314009.1.

Other sequences were from GenBank.

3.5. Schistosome infection results

Cercariae were released from infected Tricula sp. LF 50 days post-infection. Schistosome eggs were discovered in the feces of all five experimentally infected female tree shrews at 25–45 days post-infection.

4. Discussion

Of 290 wild-caught tree shrews, three (1.03%) were infected with S. sinensium, and the morphology and 18S, 12S and CO1 gene sequences of these specimens were analyzed.

Schistosoma classification is based on egg morphology and intermediate host specificity. Egg morphology is an important conserved characteristics of schistosomes. In the present study, egg size and shape, and the presence of lateral spines agreed with a previous study. Moreover, adults lack tegumental tubercles, and cercariae have eight flame cells and rest on the water surface. Display of worms are similar to S. sinensium previous recorded (Pao, 1959; Attwood et al., 2002b). Further research shows that the cercariae shed from laboratory-reared snails can reinfect captive-bred tree shrews in the laboratory. In addition, considering rodents act as definitive host of S. sinensium based on the initial report, we tried to infect two ICR mice in the laboratory. Schistosoma worms were recovered from the exposed mice. This result is expected as the ancestral host of the S. sinensium group is thought to be a rodent. The worm size obtained from the mice at the same time post-exposure was slightly smaller than that obtained in the tree shrews; these data are not to be reported elsewhere.

The 18S rDNA,12S rDNA and cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (CO1) genes are commonly used for schistosome identification. In the present study, the three loci sequencing results revealed a high degree of similarity with the related genes of S. sinensium. Phylogenetic analysis by using the maximum likelihood method and maximum parsimony method, that showed that our sample was highly similar to another Chinese strain of S. sinensium and was a sister group to other Asian schistosome species, such as S. ovuncatum, S. mekongi, S. malayensis and S. japonicum. Furthermore, our sample was related to S. mansoni, S. nasale, S. incognitum, S. spindale, and S. indicum. The results are similar to those previous studies (Attwood et al., 2002a). S. ovuncatum was considered to be the closest known relative of S. sinensium, which was first collected by Baidikul et al. (1984) in northwest Thailand and described by Attwood et al. (2002b). However, the eggs of S. ovuncatum are significantly smaller than those of S. sinensium, with a length of 70 (65–80) μm, width of 45 (40–45) μm, and spine length of 5 μm. Only the S. ovuncatum 12S sequence was analyzed in phylogene due to the limited data from GenBank. Sequence alignment between the 18S sequence of S. ovuncatum (GenBank accession no. AF465929.1) and our sample was performed using DNAMEN version 6, and the results showed very low overlop.

The geographical distribution of schistosomes depends on the distribution of snail intermediate hosts (Colley et al., 2014). Schistosoma sinensium is transmitted by freshwater Tricula snails (Pomatiopsidae: Triculinae). A previous study indicated that triculine snails originated in the highlands of Tibet and Yunnan (Liu et al., 2014). Yunnan Province is located in southwest China and has different biomes, including tropical and subtropical forests. Tricula is extensively distributed and abundant in this area (Attwood et al., 2004; Davis et al., 1986). Davis predicted that new species of snails would be discovered in Asia, and these snails would be species of Tricula or close relatives (Davis, 1980). In this report, the location where we found the Tricula snail is close to previous reported distribution area (Attwood et al., 2004).

The morphology of the shell and radula serves as the basis for classifying mollusks, this is evidenced by DNA-sequence-based phylogenies (partial nuclear and mitochondrial genes). Comparative studies were performed to improve identification. The results showed that there were slight differences in shell and radula. Tricula sp. LF shows ovate-turreted on shell shape. The shell is longer than T. bambooensis and T. ludongbini and narrower than both, the radular formula is difference that represent fewer number of inner and outer margin teeth. Morphology is closer T. bambooensis than T. ludongbini (Table 2). Moreover, 16S and 28S genes sequencing data suggest that Tricula sp. LF collected in our study site (25°04′ N, 102°19′ E) is a sister species of T. bambooensis and T. ludongbini collected from another site (25°06′ N, 99°45′ E) (Davis et al., 1986). This result confirms that the newly described pomatiopsid is a member of the genus Tricula (Triculinae). In addition, this study is the first to perform a phylogenetic analysis of Tricula sp. LF using 16S and 28S data.

The factors driving host diversity and co-evolution with Schistosoma are not fully understood (Liu et al., 2014). The reasons why the host range of S. sinensium has expanded, and whether this parasite has co-evolved with snails over a long period, more work is required in the future. These discoveries may help elucidate the evolution of Asian Schistosoma and the phylogeography of triculine snails.

5. Conclusions

We report for the first time that Tupaia belangeri (Tupaiidae) is a natural definitive host for Schistosoma sinensium, and this relationship was first identified in Lufeng, Yunnan Province, China (latitude, 25°04′50″ N; longitude, 102°19′30″ E; altitude, 1820 m). The snail intermediate host, Tricula. sp. LF, was also found in this area. The parasites and snail intermediate host were described, partial DNA sequences were used to estimate phylogenies. These findings may improve our understanding of the distribution and historical biogeography of S. sinensium and its co-evolution with snails.

Funding

This work was supported by the Yunnan Science and Technology Talent and Platform Program (Grant No. 2017HC019), The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U1702282), and the Yunnan Province Major Science and Technology Project, Yunnan (Grant No. 2017ZF007).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the parasitologist Professor Benjiang Zhou from Haiyuan College, Kunming Medical University, for the morphological identification of triculine snails. We would also like to thank Yujuan Shen for helping in schistosome identification.

Contributor Information

Jiejie Dai, Email: djj@imbcams.com.cn.

Xiaomei Sun, Email: sxm@imbcams.com.cn.

References

- Agatsuma T., Iwagami M., Liu C.X., Saitoh Y., Kawanaka M., Upatham S., Qui D., Higuchi T. Molecular phylogenetic position of Schistosoma sinensium in the genus Schistosoma. J. Helminthol. 2001;75:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood S.W., Brown D.S., Meng X.H., Southgate V.R. A new species of Tricula (pomatiopsidae: Triculinae) from sichuan province, PR China: intermediate host of Schistosoma sinensium. Syst. Biodivers. 2003:109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Attwood S.W., Fatih F.A., Mondal M.M.H., Alim M.A., Fadjar S., Rajapakse R.P.V.J., Rollinson D. A DNA sequence-based study of the Schistosoma indicum (Trematoda: digenea) group: population phylogeny, taxonomy and historical biogeography. Parasitology. 2007;134:2009–2020. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood S.W., Upatham E.S., Meng X.H., Qiu D.C., Southgate V.R. The phylogeography of asian schistosoma (trematoda: schistosomatidae) Parasitology. 2002;125:99–112. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002001981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood S.W., Panasoponkul C., Upatham E.S., Meng X.H., Southgate V.R. Schistosoma ovuncatum n. sp. (digenea: schistosomatidae) from northwest Thailand and the historical biogeography of southeast asian schistosoma Weinland, 1858. Syst. Parasitol. 2002;51:1–19. doi: 10.1023/a:1012988516995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwood S.W., Upatham E.S., Zhang Y.P., Yang Z.Q., Southgate V.R. A DNA-sequence based phylogeny for triculine snails (gastropoda: pomatiopsidae: Triculinae), intermediate hosts for schistosoma (trematoda: digenea): phylogeography and the origin of Neotricula. J. Zool. 2004;262:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Attwood S.W., Fatih F.A., Campbell I., Upatham E.S. The distribution of Mekong schistosomiasis, past and future: preliminary indications from an analysis of genetic variation in the intermediate host. Parasitol. Int. 2008;57(3):256–270. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baidikul V., Upatham E.S., Kruatrachue M., Viyanant V., Vichasri S., Lee P., Chantanawat R. Study on Schistosoma sinensium in fang district, chiangmai province, Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Publ. Health. 1984;15:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Hope M., Tiu W.U., Liu X., McManus D.P. Nuclear and mitochondrial genetic markers highly conserved between Chinese and Philippine Schistosoma japonicum. Acta Trop. 1993;55(4):217–229. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90079-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S., Leger E., Fall C.B., Borlase A., Diop S.D., Berger D., Webster B.L., Faye B., Diouf N.D., Rollinson D., Sene M., Ba K., Webster J.P. Multihost transmission of Schistosoma mansoni in Senegal, 2015-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26(6):1234–1242. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.200107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colley D.G., Bustinduy A.L., Secor W.E., King C.H. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2014;383(9936):2253–2264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G.M. Snail hosts of Asian Schistosoma infecting man: origin and coevolution. Malacol. Rev. 1980:195–238. [Google Scholar]

- Davis G.M., Guo Y.H., Hoagland K.E., Chen P.L., Zheng L.C., Yang H.M., Chen D.J., Zhou Y.F. Anatomy and systematics of Triculini (Prosobranchia: pomatiopsidae: Triculinae), freshwater snails from Yunnan, China, with descriptions of new species. Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Phila. 1986;138:466–575. [Google Scholar]

- Devkota R., Brant S.V., Loker E.S. The Schistosoma indicum species group in Nepal: presence of a new lineage of schistosome and use of the Indoplanorbis exustus species complex of snail hosts. Int. J. Parasitol. 2015;45(13):857–870. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer G.J., Kitikoon V., Lohachit C. Morphology and life cycle of Schistosoma sinensium Pao, 1959, from northwest Thailand. J. Parasitol. 1989;75:98–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W., Liu D., Zhou S. Discovery of Schistosoma sinensium in NaPo county, GuangXi province of China. Chin. J. Parasitol. Parasit. Dis. 2003;21(1) 59-59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.P., Norman B.F., Borrett H.E., Attwood S.W., Mondal M.M.H., Walker A.J., Webster J.P., Jayanthe Rajapakse P.R.V., Lawton S.P. Divergence across mitochondrial genomes of sympatric members of the Schistosoma indicum group and clues into the evolution of Schistosoma spindale. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):2480. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57736-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D.A., Kane R.A., Rollinson D. Small subunit (18S) ribosomal RNA gene divergence in the genus Schistosoma. Parasitology. 1993;107:147–156. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000067251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kameda Y., Kato M. Terrestrial invasion of pomatiopsid gastropods in the heavy-snow region of the Japanese Archipelago. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011;11:118. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruatrachue M., Upatham E.S., Sahaphong S., Tongthong T., Khunborivan V. Scanning electron microscopic study of the tegumental surface of adult Schistosoma sinensium. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Publ. Health. 1983;14:427–438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton S.P., Hirai H., Ironside J.E., Johnston D.A., Rollinson D. Genomes and geography: genomic insights into the evolution and phylogeography of the genus Schistosoma. Parasites Vectors. 2011;4:131. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T.H., Blair D., Agatsuma T., Humair P.F., Campbell N.J., Iwagami M., Littlewood D.T., Peacock B., Johnston D.A., Bartley J., Rollinson D., Herniou E.A., Zarlenga D.S., McManus D.P. Phylogenies inferred from mitochondrial gene orders-a cautionary tale from the parasitic flatworms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17(7):1123–1125. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Huo G.N., He H.B., Zhou B., Attwood S.W. A phylogeny for the pomatiopsidae (Gastropoda: rissooidea): a resource for taxonomic, parasitological and biodiversity studies. BMC Evol. Biol. 2014;14:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockyer A.E., Olson P.D., Ostergaard P., Rollinson D., Johnston D.A., Attwood S.W., Southgate V.R., Horak P., Snyder S.D., Le T.H., Agatsuma T., McManus D.P., Carmichael A.C., Naem S., Littlewood D.T. The phylogeny of the Schistosomatidae based on three genes with emphasis on the interrelationships of Schistosoma Weinland, 1858. Parasitology. 2003;126:203–224. doi: 10.1017/s0031182002002792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbi S.R. In: Nucleic Acids. II: the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Hillis D.M., Moritz C., Mable B.K., editors. Mol. Syst; 1996. pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- Pao T.C. The description of a new schistosome Schistosoma sinensium sp. nov. (Trematoda: schistosomatidae) from Szechuan Province. Chin. Med. J. 1959;78 278-278. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade C.M., Mordan P.B. Evolution within the gastropod mollusks; using the ribosomal RNA gene-cluster as an indicator of phylogenetic relationshipsnships. J. Molluscan Stud. 2000:565–570. [Google Scholar]

- Webster B.L., Littlewood D.T. Mitochondrial gene order change in schistosoma (Platyhelminthes: digenea: schistosomatidae) Int. J. Parasitol. 2012;42(3):313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Chen S.Y., Nie W.H., Jiang X.L., Yao Y.G. Evaluating the phylogenetic position of Chinese tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis) based on complete mitochondrial genome: implication for using tree shrew as an alternative experimental animal to primates in biomedical research. J. Genet. Genomics. 2012;39:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Zhang Y., Liang B., Lü L.B., Chen C.S., Chen Y.B., Zhou J.M., Yao Y.G. Tree shrews under the spot light: emerging model of human diseases. Zool. Res. 2013;34:59–69. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1141.2013.02059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Qiu Z., Yang W., Yao B., Bi S. Discovery of Schistosoma sinensium in WeiShan county, YunNan province of China. Chinese J. Parasit. Dis. 1995;8 68-68. [Google Scholar]