Abstract

Background

Serum lipids and glycemic dysregulation are the known characteristics of β- thalassemia major (β-TM). Here, we evaluated the association of these disorders with insulin resistance (IR), oxidative stress and serum ferritin values in patients with β-TM.

Methods

This case-control study was performed in thalassemia unite of Darab Hospital (Darab, Fars province, Iran) from December 2016 to December 2017. Forty-eight patients with β-TM and 33 healthy individuals were enrolled. Serum fasting blood sugar (FBS), insulin, total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high density lipoprotein (HDL), low density lipoprotein (LDL), ischemia modified albumin (IMA), and ferritin were measured. The values of HOMA-IR, LDL: TG ratio, atherogenic index (AI), atherogenic index of plasma (AIP), and coronary risk index (CRI) were calculated.

Results

The level of serum ferritin, IMA, FBS, TG, AIP, LDL: TG ratio, and the prevalence of IR (HOMA-IR < 3.8) were significantly higher while TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and AI were significantly lower in the patients compared to the control group. In patient with β-TM, serum ferritin revealed to have a positive association with serum insulin, HOMA-IR, AI, and CRI levels while serum IMA showed positive association with TG and AIP and inverse association with hypocholesterolemia. HOMA-IR had positive correlation with HDL levels.

Conclusions

Oxidative stress and iron overload are predictors of serum glycemic and lipid dysregulation, suggesting possible beneficial effect of antioxidants and efficient iron chelating therapy in reducing the risk of metabolic disorders in β- thalassemia.

Keywords: β- thalassemia major; Lipid profile; Oxidative stress, Insulin resistance, Iron overload

Introduction

Severe anemia due to defect in the synthesis of hemoglobin and hemolysis can endanger the life of β- thalassemia major (β-TM) patients; therefore, the span and patient’s quality of life is highly dependent on regular blood transfusion [1]. Nonetheless, blood transfusion causes iron accumulation in the patients. Despite many benefits of iron chelating, iron overload remains to be a major challenge in managing patients with β-TM. Iron overload triggers oxidative stress(OS), and increases the risk of several complications, such as diabetes mellitus, hepatocytes damage, and coronary heart disease (CHD) in patients with β- thalassemia [2, 3]. Therefore, understanding the responsible pathological mechanisms that generate these abnormalities is of great interest to prevent and management β-TM complications.

Disturbances in serum lipids and carbohydrates homoeostasis as well as OS were documented in β-TM [4]. Increase in serum levels total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) are the well-known causative factors and predictors of CHD development [5]. Nevertheless, it has been well documented that the values of serum TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C are significantly lowered in patients with β-TM compared to normal subjects [6, 7]. In order to better predict CHD risk, several indices of dyslipidemia including LDL: HDL ratio ( atherogenic index; AI), log TG: HDL ratio (atherogenic index of plasma; AIP), TC: HDL ratio (coronary risk index ; CRI) are used to describe the significance of dyslipidemia in increasing risk of CHD in patients with β-TM [8]. Hyperglycemia, glucose intolerance, decreased beta cell activity and insulin insensitivity were reported in patients with β-TM [9]. OS due to decrease in antioxidant defense system and increase iron- induced ROS production as well as the benefits of antioxidant administration to overcome these disorders were implicated in patients with β-TM [10]. Several markers including malondialdehyde [10], isoprostane [11] as well as ischemia modified albumin (IMA) [12] were applied to measure OS in the patients with β-TM. More than half of total antioxidant activity of human serum is supplied by serum albumin. Oxidative damage to the N-terminal of domain, during OS converts albumin to IMA. Reduced affinity of a number of metals, such as cobalt for binding to IMA is the basis for albumin cobalt binding (ACB) test, which is used to measure serum IMA levels [13]. Several recent studies [12, 14, 15], have revealed increased serum level of IMA in patients with β-TM, using ACB test, suggesting increased level of OS in these patients.

The serum level of lipid and lipoproteins are affected by a number of physiological and pathological mechanisms. Age, gender, and population based variables, such as nutritional habits and genetic background are amongst the physiological factors that can affect lipid homeostasis [16]. Insulin resistance [11], liver damage [17], OS [6], and spelenctomy [18] are pathological mechanisms that can affect lipid and carbohydrate metabolism of patients with β-TM. To the best of our knowledge, no study has ever addressed the interaction between these pathological factors on serum lipids and glucose dysregulation in patients with β-TM. In the present study, we assessed the interaction of these pathological variables on dyslipidemia and glycemic abnormalities in the age and gender matched control and patients with β-TM, selected from a small population (Darab, Iran) with the same genetic background and nutritional habits.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This case-control study was approved by the local Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Code: IR.SUMS.REC.1397.1033). After explaining the study objectives, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Forty-eight patients with β-TM, attending the thalassemia unit of the pediatric department of Imam Hasan Hospital (Darab, Fars province, Iran) between December 2016 and December 2017 were investigated. The patients were diagnosed according to physical examination data and results of laboratory tests including complete blood count (CBC) and hemoglobin electrophoresis. All patients were under regular blood transfusion and iron-chelation and folate therapy. Exclusion criteria were β-TM patients with diabetes mellitus, hepatitis B or C, or those taking pharmacological agents such as insulin, steroids, oral antidiabetics, and lipid lowering drugs. Thirty-three age- and gender-matched healthy controls with normal serum lipids and glucose levels and without any major diseases affecting serum glycemic and lipid levels were enrolled in this study as the control group. Blood samples were collected from participants between 8:00 and 9:00 a.m. after 12 h over night fasting and in patients just prior to blood transfusion.

Serum biochemical determination

The commercial kits used to determine serum biochemical determination including glucose, lipids, uric acid, liver function tests (LFT) levels were purchased from Pars Azmun Company (Tehran, Iran). Serum insulin level was measured, using Monobind ELISA kit (Monobind, USA). The kit for ferritin level was bought from Pishtazteb Company (Tehran, Iran). All biochemical determinations were according to the manufacture’s instruction. Homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-ir), quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) and β-cell function (HOMA-B %) were calculated, using the following formulas [QUICKI = 1/ (log [fasting insulin] + log [fasting glucose]); HOMA-IR = ([fasting glucose] × [fasting insulin])/22.5; HOMA-B= [20 × fasting insulin / (fasting glucose − 3.5] [19]. The LDL-cholesterol level was calculated, using freidewald equation.

Serum IMA and ferritin determination

Serum IMA levels were measured, using ACB test as described elsewhere [20]. In ACB method, 50 µL of cobalt chloride solution (1 g/L) is added to 200 µl of the serum and followed by vigorous mixing, and 10-min incubation at room temperature. Dithiothreitol (DTT; Sigma-Aldrich) solution (50 µL; 1.5 g/L solution) is then added and mixed. After 2 min of incubation, 1.0 mL of saline solution (NaCl, 9.0 g/L) is added to stop the reaction. The blank solution is prepared similarly with the exclusion of DTT. Absorbance of assay mixture is then measured against blank at 470 nm and the level of IMA in each sample is expressed as unit of absorbance (ABSU). A direct relationship exists between the level of IMA in the sample and ABSU of assay mixture. IMA index is calculated from IMA/serum albumin concentration. Ferritin level is measured by ELISA method (Pishtazteb, Iran).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were done, using SPSS software (version 22, Chicago, IL, USA). Normal distribution of the variables was checked by the Kolmogorov- Smirnov test. Analysis of covariance was performed to compare groups after adjustment for BMI. Spearman’s test were carried out to compare the variables in the control and patients’ groups and to evaluate the linear correlations amongst parameters. Following correlation analysis, those variables with significant correlation were entered into multiple stepwise linear regression analysis to determine which factors were significantly and independently associated with the serum glycemic and lipid level. For all analyses, P values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

In the patient group, 52.1% (25 subjects) were males and 47.9% (23 subjects) were females. The same percentage of male (48.5%) and female (51.5%) was observed in healthy controls (P = 0.960). No significant difference was observed in the mean age of patients (21.8 ± 6.4 years; range 9–32) and the controls (24.1 ± 5.0 years ; range 11–32) (p = 0.113). However, the control group had higher values of BMI (23.6 ± 4.2) than the patients (19.5 ± 2.8) (p < 0.001). All patients received iron chelating therapy and 46% of the patients (22 subjects) were splenectomized. The patients’ age at diagnosis ranged from 0.25 to 4.5 years (median of 0.75 years). Their β-TM duration ranged from 8 to 31.5 years (median of 21.4 years). A positive correlation between duration of β-TM and serum globulins values(r = 0.485, p = 0.001) was observed. No correlations were found between β-TM duration and other biochemical characteristics.

Serum glycemic condition in the controls and patients

After adjusting for BMI, the mean of FBS values in patients with β-TM (103.0 ± 12.8) was higher compared to the control group (94.12 ± 5.2) (p = 0.002) while index of β- cell function (HOMA-B %) in the patients (127.8 ± 89.5) was comparable to the control group (138.86 ± 60.17) (p = 0.445). In the patient group, 39.58% had normal FBS (70–99 mg/dl) and 60.42% had impaired FBS (100–125 mg/dl). After adjusting for BMI, the levels of serum insulin (12.7 ± 7.2), HOMA-ir (3.28 ± 2.10), and QUICKI (0.329 ± 0.025) were not significantly different between the patients with β-TM and controls (Insulin = 11.73 ± 3.9; HOMA-ir = 2.75 ± 0.94; QUICKI = 0.331 ± 0.015). According to HOMA-ir index, 29.16% of the patients had insulin resistance (HOMA-IR ≥ 3.8) while in 15.15% of the controls, insulin resistance was detected.

Serum lipid profile in the controls and patients

Table 1 shows the values of serum lipids in the patients with β-TM and the controls. After adjusting for BMI, the serum level of TC and lipoproteins (LDL-C and HDL-C) were significantly (p < 0.001) lower in the patients while the level of serum TG was significantly higher in the patients (p < 0.001). The ratio of LDL/TG (p < 0.001) was significantly lower in the patients compared to control group. AIP was significantly higher in patients with β-TM compared to that of controls. Hypercholesterolemia (TC ≥ 200 mg/dl) was more prevalent in the controls (27.3%) compare to the patients (0.0%) (p < 0.001). Furthermore, low level of HDL-C (≤ 40 mg/dl) was observed in 93.7% and 24.2% of the patients and control group, respectively (p < 0.001). In the patient group, 100% had normal (< 110 mg/dl whereas in the control group 54.5% had normal, 21.3% were borderline and 24.2% had high LDL-C level.

Table 1.

Serum lipid profile of the controls and patients

| Variables | Patients (n = 48) | Controls (n = 33) | P values* |

|---|---|---|---|

| TG (mg/dl) | 121.0 ± 46.3 | 93.9 ± 44.3 | < 0.001 |

| TC (mg/dl) | 107.7 ± 22.9 | 172.2 ± 40. 6 | < 0.001 |

| LDL- C(mg/dl) | 54.2 ± 20.7 | 102.8 ± 38.1 | < 0.001 |

| HDL- C(mg/dl) | 30.0 ± 7.3 | 45.5 ± 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| LDL/TG | 0.54 ± 0.32 | 1.28 ± 0.64 | < 0.001 |

| AIP(log TG/HDL) | 0.58 ± 0.26 | 0.27 ± 0.22 | < 0.001 |

| AI(LDL/HDL) | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.091 |

| CRI(TC/HDL) | 3.7 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.9 | 0.191 |

n: Number of participants. The data are means ± SD.*All P values were adjusted by BMI

Comparison of serum liver function tests between the patients and controls

The data of liver function tests of all participants is shown in the Table 2. After adjusting for BMI, the means of serum alanine and aspartate transaminase (AST and ALT) and alkaline phosphatase( ALP) activities in the patients were significantly higher than those of the controls (p < 0.001, P = 0.004, and p = 0.004, respectively). Serum total bilirubin (TB) and direct bilirubin (DB) values were also higher in the patients compared to those of healthy subjects (p < 0.001). The means of serum total protein (TP) and globulin (Glu) were significantly higher in patients with β-TM compared to control group (p < 0.001), whereas means of serum albumin (Alb) was significantly lower in the patients compared to that of the control group (p = 0.007).

Table 2.

Liver function tests in the controls and patients

| Variables | Patients (n = 48) | Controls (n = 33) | P values* |

|---|---|---|---|

| AST (U/l) | 51 ± 36 | 21 ± 7 | < 0.001 |

| ALT(U/l) | 53 ± 53 | 25 ± 19 | 0.004 |

| ALP(U/l) | 445 ± 271 | 209 ± 95 | 0.004 |

| TB(g/l) | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| DB(g/l) | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| TP(g/dl) | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Alb (g/dl) | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 0.007 |

| Glu (g/dl) | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 |

n: Number of subjects. The data are means ± SD. *All P values are adjusted by BMI

Comparison of serum oxidative markers and ferritin levels between the patients and controls

After adjusting for BMI, the serum levels of IMA (0.499 ± 0.122) and IMA/ albumin ratio (0.11 ± 0.03) were significantly (p < 0.001) higher in the patients with β-TM compared to IMA value (0.369 ± 0.057) and IMA/albumin ratio (0.08 ± 0.01) in the controls. Patients with β-TM had significant (p = 0.004) higher values of serum ferritin (2717 ± 3411) compared to controls (75 ± 74). Moreover, in the patient group, 19 patients (39.6%) had serum ferritin < 1000 ng/ml, 15 patients (31.2%) had values level between 1000 and 2500 ng/ml, and 14 patients (29.2%) had serum ferritin > 2500 ng/ml. After adjusting for BMI, the levels of serum uric acid was significantly higher in patients with β-TM (5.1 ± 2.1) compared to controls (4.8 ± 1.6) (p = 0.034).

Association of serum glycemic parameters with various parameters

For the serum glycemic parameters, a significant association between serum insulin levels with serum ferritin levels (r = 0.304, p = 0.036) and inverse correlation with splenectomy (r = − 0.303, p = 0.036) were observed, following spearman bivariate correlation analysis. HOMA-ir also significantly correlated with serum ferritin level (r = 0.311, p = 0.032) and showed inverse correlation with splenectomy (r = − 0.293, p = 0.043) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of serum glycemic parameters with various parameters in the patient group

| Variables | Gender | Age | BMI | Ferritin | Splenectomy | ALT | IMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBS |

r = 0.041 p = 0.784 |

r=-0.063 p = 0.673 |

r = 0.021 p = 0.890 |

r = 0.236 p = 0.106 |

r = 0.021 p = 0.887 |

r = 0.144 p = 0.329 |

r=-0.019 p = 0.896 |

| Insulin |

r = 0.107 p = 0.470 |

r=-0.168 p = 0.254 |

r=-0.015 p = 0.922 |

r = 0.304 p = 0.036* |

r= -0.303 p = 0.036* |

r = 0.111 p = 0.453 |

r= -0.151 p = 0.306 |

| HOMA-ir |

r = 0.101 p = 0.495 |

r=-0.199 p = 0.174 |

r=-0.008 p = 0.955 |

r = 0.311 p = 0.032* |

r=-0.293 p = 0.043* |

r = 0.140 p = 0.344 |

r= -0.150 p = 0.309 |

| QUICKI |

r=-0.101 p = 0.495 |

r = 0.199 p = 0.174 |

r = 0.008 p = 0.955 |

r=-0.311 p = 0.032* |

r = 0.293 p = 0.043* |

r = − 0.140 p = 0.344 |

r = 0.150 p = 0.309 |

| HOMA- B |

r= -0.071 p = 0.633 |

r=-0.020 p = 0.894 |

r=-0.014 p = 0.923 |

r=-0.093 p = 0.531 |

r=-0.220 p = 0.132 |

r = − 0.012 p = 0.936 |

r= -0.102 p = 0.488 |

Spearman’s correlation bivariate analysis was used to test the relationships between parameters.* shows significant difference at P < 0.05

Serum lipids correlations in β-TM patients

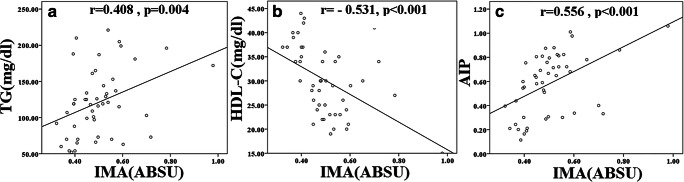

The possible correlations of serum lipids and lipoproteins levels with various parameters were evaluated using Spearman bivariate correlation analysis. Serum TG concentration was directly associated with serum IMA values(r = 0.408, p = 0.004) levels (Table 4). Spearman bivariate correlation analysis revealed significant inverse correlations between serum values of TC and IMA (r = − 0.377, p = 0.008), and between serum ALT and TC (r = 0.415, p = 0.003). However, in the stepwise multiple linear regression analysis serum IMA levels (β: -0.330, P = 0.022) remained the only significant predictor of TC in β-TM subjects. Serum HDL levels in the patient group were significantly associated with serum IMA (r = − 0.531, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1) and HOMA-ir (r = 0.323, p = 0.027) levels.

Table 4.

Correlations between lipid profile and various parameters in the patient group

| Variables | Gender | Age | BMI | Ferritin | Splenectomy | ALT | IMA | HOMA-ir |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG |

r=-0.140 p = 0.342 |

r=-0.055 p = 0.710 |

r = 0.169 p = 0.256 |

r = 0.234 p = 0.109 |

r= -0.021 p = 0.887 |

r = 0.281 p = 0.053 |

r = 0.408 p = 0.004* |

r=-0.159 p = 0.279 |

| TC |

r = 0.175 p = 0.235 |

r=-0.014 p = 0.926 |

r=-0.085 p = 0.570 |

r = 0.266 p = 0.068 |

r = 0.242 p = 0.098 |

r = 0.415 p = 0.003* |

r= -0.377 p = 0.008* |

r = 0.056 p = 0.707 |

| HDL-C |

r = 0.256 p = 0.082 |

r = 0.010 p = 0.946 |

r=-0.224 p = 0.135 |

r=-0.031 p = 0.838 |

r= -0.003 p = 0.983 |

r=-0.013 p = 0.931 |

r = − 0.531 p < 0.001* |

r = 0.323 p = 0.027* |

| LDL-C |

r = 0.188 p = 0.205 |

r=-0.045 p = 0.764 |

r=-0.127 p = 0.399 |

r = 0.239 p = 0.105 |

r = 0.263 p = 0.075 |

r = 0.403 p = 0.005* |

r = − 0.425 p = 0.003* |

r = 0.007 p = 0.961 |

| LDL-C/TG |

r = 0.260 p = 0.077 |

r = 0.056 p = 0.711 |

r=-0.268 p = 0.072 |

r = 0.024 p = 0.872 |

r = 0.126 p = 0.400 |

r = 0.030 p = 0.842 |

r= -0.581 p < 0.001* |

r=-0.174 p = 0.243 |

| AIP |

r= -0.268 p = 0.068 |

r=-0.007 p = 0.961 |

r = 0.228 p = 0.128 |

r = 0.160 p = 0.283 |

r = 0.009 p = 0.950 |

r = 0.201 p = 0.176 |

r = 0.556 p < 0.001* |

r=-0.259 p = 0.079 |

| AI |

r = 0.067 p = 0.652 |

r=-0.108 p = 0.468 |

r=-0.012 p = 0.938 |

r = 0.345 p = 0.018* |

r = 0.303 p = 0.038* |

r = 0.480 p = 0.001* |

r= -0.108 p = 0.470 |

r=-0.163 p = 0.273 |

| CRI |

r= -0.088 p = 0.557 |

r=-0.113 p = 0.451 |

r=-0.153 p = 0.309 |

r = 0.377 p = 0.009* |

r = 0.220 p = 0.137 |

r = 0.437 p = 0.002* |

r = 0.199 p = 0.181 |

r=-0.219 p = 0.140 |

Spearman’s correlation bivariate analysis was used to test the relationships between parameters. P < 0.05 was considered as significant difference.

Fig. 1.

The represented graphs revealed correlation between serum IMA and serum triglyceride (TG), high density lipoprotein –cholesterol (HDL-C), and atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) in the patients with thalassemia

Stepwise multiple linear regression data revealed that both of serum IMA level (β: − 0.466, p < 0.001) and HOMA-ir (β: 0.324, p = 00. 01) were significant predictors of serum HDL-C levels. On the basis of Spearman bivariate correlation analysis, serum LDL-C levels were significantly associated with IMA level (r = − 0.425, p = 0.003) and serum ALT(r = 0.403, p = 0.005). The findings of the stepwise multiple linear regression analyses revealed that serum IMA level (β: -0.393, p = 0.006) is significant predictors of serum LDL-C concentration. AIP and LDL-C /TG ratio exhibited positive (r = 0.556, p < 0.001) and negative (r = -0.581, p < 0.001) associations with serum IMA level, respectively. Spearman bivariate correlation analysis revealed significant associations between AI with circulating ferritin level (r = 0.345, p = 0.018), serum ALT (r = 0.480, p = 0.001), and splenectomy(r = 0.303, p = 0.038). The results of the stepwise multiple linear regression analyses revealed that both of serum ferritin level (β: 0.309, p = 0.027) and serum splenectomy (β: 0.299, p = 0.033) are significant predictors of serum AI levels in patients with β-TM. Results of stepwise multiple linear regression analyses revealed that serum ferritin level (β: 0.385, p = 0.008) is significant predictors of CRI values in the β-TM patients.

Association of liver function tests with various parameters

The possible correlations between LFT and other parameters in β-TM patients group were evaluated, using Spearman bivariate correlation analysis. In patients with β-TM, AST levels positively correlated with serum ferritin level (r = 0.642, p < 0.001) (Table 5). Spearman bivariate correlation analysis also revealed significant associations between serum ALT levels and serum ferritin (r = 0.636, p < 0.001). Serum ALP activity revealed a significant negative correlation with the patients’ age (r=-0.624, p < 0.001), patients’ BMI (r= -0.407, p = 0.003), and ferritin level (r = 0.543, p < 0.001). However, in the stepwise multiple linear regression analysis patients’ age (β: -0. -0.533, p < 0.001) remained the only significant predictor of serum ALP level in patients with β-TM. Serum TB and DB levels in the patient group were significantly associated with serum IMA (r = 0.642, p < 0.001 and r = 0.373, p = 0.009, respectively) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlations between liver function tests and various parameters in the patient group

| Variables | Gender | Age | BMI | Ferritin | Splenectomy | IMA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST |

r=-0.127 p = 0.392 |

r=-0.069 p = 0.643 |

r=-0.030 p = 0.840 |

r = 0.642 p < 0.001* |

r = 0.079 p = 0.596 |

r=-0.134 p = 0.364 |

| ALT |

r=-0.060 p = 0.684 |

r=-0.189 p = 0.198 |

r=-0.142 p = 0.340 |

r = 0.636 p < 0.001* |

r = 0.026 p = 0.863 |

r= -0.127 p = 0.390 |

| ALP |

r=-0.141 p = 0.337 |

r=-0.624 p < 0.001* |

r=-0.397 p = 0.006* |

r = 0.543 p < 0.001* |

r= -0.180 p = 0.222 |

r = − 0.291 p = 0.045 |

| TB |

r=-0.101 p = 0.495 |

r = 0.1681 p = 0.255 |

r=-0.135 p = 0.6366 |

r=-0.288 p = 0.047 |

r=-0.107 p = 0.468 |

r = 0.642 p < 0.000* |

| DB |

r= -0.145 p = 0.326 |

r=-0.165 p = 0.2636 |

r=-0.069 p = 0.647 |

r=-0.264 p = 0.069 |

r=-0.138 p = 0.351 |

r = 0.373 p = 0.009* |

| Alb |

r = 0.196 p = 0.182 |

r=-0.262 p = 0.072 |

r=-0.044 p = 0.769 |

r=-0.044 p = 0.765 |

r=-0.242 p = 0.097 |

r = 0.217 p = 0.138 |

| Glu |

r= -0.088 p = 0.554 |

r=-0.456 p < 0.001* |

r=-0.346 p = 0.017* |

r=-0.163 p = 0.268 |

r = 0.198 p = 0.177 |

r = 0.067 p = 0.650 |

Spearman’s correlation bivariate analysis was used to test the relationships between parameters. P < 0.05 was considered as significant difference.

Discussion

Our data revealed iron overload in association with dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, liver dysfunction, and OS in the patients who were treated with chelating agents. Furthermore, our data also showed that combination of iron overload, insulin resistance, OS, and splenectomy can affect serum lipids and glycemic abnormalities, suggesting the importance of adequate and effective iron chelating therapy in association with ameliorating OS and insulin resistance in treatment of metabolic disorders in patients with β-TM.

Serum ferritin is used as a sensitive marker to evaluate iron overload. In spite of iron chelating therapy, our results showed a high prevalence (60% of the patients) of iron overload (ferritin > 1000 ng/mL) in patients with β-TM [21], suggesting ineffective iron chelation therapy. IMA is a serum marker of OS, produced following oxidative damage to the N-terminal of serum albumin. Several conditions including metabolic disorders [22], cardiac ischemia [23], and hyperglycemia [24] are associated with OS. In accordance with the finding of previous studies [12, 14, 15], our data revealed a significant increase in the serum IMA values in the patients with β-TM, suggesting increased OS in these patients. Increase in hydroxyl free radicals production by the Fenton reaction and iron overload are mentioned as the causes of IMA formation in patients with thalassemia [13]. Increase in FBS and higher rate of insulin resistance was observed in our patients with β-TM, which are in agreement with the results reported by several previous studies [9, 25]. As expected and in agreement with many previous studies [26], evaluation of liver function test in our patients showed abnormalities in all aspects of normal liver function. Significant increases in serum AST and ALT levels which are highly correlated with serum ferritin levels, suggesting iron overload-induced liver parenchymal damage. Also, significant decrease in serum albumin values in association with increases in serum globulins levels were observed in the patients. Inverse correlation between serum albumin levels and serum ALT level suggests that decrease in serum albumin levels may reflect decreased synthesis of albumin by the liver. Serum globulins comprise a wide spectrum of proteins including α, β, and γ globulins that are synthesized and secreted into circulation by the liver and lymphocytes. Increase in serum globulins may be a compensatory mechanism in response to decreased in serum albumin level. Furthermore, some studies revealed increase in serum γ globulins levels in β-TM patients [27, 28]. While the exact mechanisms that may attribute in increase in immunoglobulin levels in β-TM patients is not clearly understood, stimulation of immune system by infections, continuous exposure to antigen due repeated transfusion, and altering immune response by iron overload are possible mechanisms. With respect to serum total protein concentration, significant increase was observed in the patients, which is in agreement with a report by Ayyash e al [29]. Due to decrease of serum albumin in our patients, increase in serum total protein might be the consequence of increase in serum globulins, including γ globulins.

Finally, our data specifically revealed a significant decrease in the levels of serum TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C in patients with β-TM compared to the healthy subjects. These data are in line with the findings reported by numerous studies, investigating other populations [6, 7, 30, 31].CHD development is highly associated with alteration in lipoprotein metabolism particularly decrease in circulating HDL-C and increase in LDL-C values. Given the decrease in LDL-C, decrease in HDL-C is apparently the most important cause of CHD in β-TM patients. About 49.0% of our patients had very low HDL-C values (lower than 30 mg/dl) while none of the age-matched controls had HDL-C below 30 mg/dl, suggesting higher risk of CHD in our β-TM patients.

Patients with β-TM enrolled in our study had higher level of serum TG concentration compared to the healthy subjects, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [8, 32, 33]. Contradictory results were reported by other researchers who reported no significant difference in serum TG level between healthy individuals in comparison with patients with β-TM [34] and Kassab-Chekir et al. [25]. These discrepancies might be due to genetic variation, lifestyle and nutrition habits in various studied populations. In line with the data of previous studies [8, 31], our data found a higher level of AIP in the patients with β-TM in comparison compared to the normal healthy subjects. A direct association between AIP and atherosclerosis was detected in patients with β-TM [8], suggesting increased risk of atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease in patients with β-TM.

To find possible mechanisms underlying dyslipidemia observed in our patients, the association between serum lipid with iron overload, OS, insulin resistance, liver damage, and spelenectomy were evaluated. Results from the correlation and regression analyses showed that serum IMA was positive and independent predictors of serum TG levels in the patients. These finding are in line with those reported by others, suggesting a positive correlation between OS with TG concentrations [6, 35]. Our finding showed an inverse correlation between serum TC and LDL-C with serum IMA. These findings are in line with the results of previous studies that had proposed a role of OS in the etiology of hypocholestermia in the patients with β-TM [36].

Significant positive association between serum TC and LDL-C values with HOMA-ir are indicated in both thalssemic [37] and non-thalasemic [38] individuals. However, our results failed to show such association. Furthermore, correlation analyses showed a significant positive correlation between IMA level and AIP while it inversely correlated with HDL-C values. Moreover, according to multivariate regression analyses, IMA was inversely associated with HDL-C and positively associated AIP, suggesting a significant impact of OS in the decreasing HDL-C values and increasing AIP in the patients with β-TM. Due the association of reduced HDL-C and increased AIP with the development of atherosclerosis [8], our findings suggest possible protective role of antioxidant in against CHD in the patients with β-TM.

Genetic background and nutritional habits [16], age, gender, blood transfusion, and iron chelating therapy could have affected serum lipid concentration. Strengths of our study include adjustment of physiological variables such as age, gender and patients selection that received blood transfusion and iron chelating treatment. We also selected both controls and patients from the same population with similar genetic and dietary background. Our study had two main limitations. The first was the use of FBS instead of methods with higher diagnostic capabilities including continuous monitoring of serum glucose and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for the detection of glycemic abnormalities [39]. However, these methods are time-consuming and cause some inconvenience to the patients and we failed to use them. The second is that the dose and frequency of iron chelator therapy are not evaluated in our study.

In conclusion, our results provide evidence that in spite of treatment with iron chelating drugs, patients with β-TM suffered from OS, liver dysfunction, and metabolic disorders including lipoproteins abnormalities and insulin resistance. Furthermore, it is inferred that OS, iron overload, spelenectomy, and insulin resistance are interrelated mechanisms responsible for lipid disorders, which might lead to atherosclerosis and subsequent cardiovascular disease in patients with β-TM. More efficient therapeutic strategies that could ameliorate OS and insulin resistance should be considered in the treatment of transfusion-dependent thalassemic patients.

Acknowledgements

This study has been extracted from the Pharm D thesis of Soheila Setoodeh and was financially supported by Grant Number 93-01-05-8599 from Vice-chancellor for Research Affairs of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran. The authors wish to thank Mr. H. Argasi at the Research Consultation Center (RCC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for his invaluable assistance in editing this manuscript.

Author contributions

SS conducted the research, analyzed and interpreted the data. MK conducted a part of the research, analyzed and helped interpreting the data and contributed to writing the manuscript. MAT provided research material, discussed the project, analyzed and interpreted the data, and contributed to writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict interest declared by the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Soheila Setoodeh, Email: soheila.setoodeh@gmail.com.

Marjan Khorsand, Email: ma.kh58@yahoo.com.

Mohammad Ali Takhshid, Email: takhshidma@sums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Musallam KM, Cappellini MD, Wood JC, Taher AT. Iron overload in non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a clinical perspective. Blood reviews. 2012;26:16-S9. doi: 10.1016/S0268-960X(12)70006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koohi F, Kazemi T, Miri-Moghaddam E. Cardiac complications and iron overload in beta thalassemia major patients—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of hematology. 2019;98(6):1323–31. doi: 10.1007/s00277-019-03618-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motta I, Mancarella M, Marcon A, Vicenzi M, Cappellini MD. Management of age-associated medical complications in patients with β-thalassemia. Expert review of hematology. 2020;13(1):85–94. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2020.1686354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noetzli LJ, Mittelman SD, Watanabe RM, Coates TD, Wood JC. Pancreatic iron and glucose dysregulation in thalassemia major. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(2):155–60. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wadhera RK, Steen DL, Khan I, Giugliano RP, Foody JM. A review of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, treatment strategies, and its impact on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(3):472–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boudrahem-Addour N, Izem-Meziane M, Bouguerra K, Nadjem N, Zidani N, Belhani M, et al. Oxidative status and plasma lipid profile in β-thalassemia patients. Hemoglobin. 2015;39(1):36–41. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2014.979997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ragab SM, Safan MA, Obeid OM, Sherief AS. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 (Lp-PLA2) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and their relation to premature atherosclerosis in β-thalassemia children. Hematology. 2015;20(4):228–38. doi: 10.1179/1607845414Y.0000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherief LM, Dawood O, Ali A, Sherbiny HS, Kamal NM, Elshanshory M, et al. Premature atherosclerosis in children with beta-thalassemia major: New diagnostic marker. BMC Pediatr. 2017;17(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12887-017-0820-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo Y, Bajoria R, Lai Y, Pan H, Li Q, Zhang Z, et al. Prevalence of abnormal glucose homeostasis in Chinese patients with non-transfusion-dependent thalassemia. Diabetes metabolic syndrome obesity: targets therapy. 2019;12:457. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S194591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hezaveh ZS, Azarkeivan A, Janani L, Shidfar F. Effect of quercetin on oxidative stress and liver function in beta-thalassemia major patients receiving desferrioxamine: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. 2019;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Tselepis AD, Hahalis G, Tellis CC, Papavasiliou EC, Mylona PT, Kourakli A, et al. Plasma levels of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A(2) are increased in patients with beta-thalassemia. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(11):3331–41. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M007229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al IO, Ayçiçek A, Ersoy G, Bayram C, Neselioglu S, Erel Ö. Thiol Disulfide Homeostasis and Ischemia-modified Albumin Level in Children With Beta-Thalassemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41(7):e463-e6. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0000000000001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Awadallah SM, Atoum MF, Nimer NA, Saleh SA. Ischemia modified albumin: An oxidative stress marker in β-thalassemia major. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413(9–10):907–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adly AAM, ElSherif NHK, Ismail EAR, Ibrahim YA, Niazi G, Elmetwally SH. Ischemia-modified albumin as a marker of vascular dysfunction and subclinical atherosclerosis in β-thalassemia major. Redox Rep. 2017;22(6):430–8. doi: 10.1080/13510002.2017.1301624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbeblawy N, Abdelmaksoud A, Elguindy W, Elshinawy D, Abdelwahed G. Ischemia modified albumin in Egyptian patients with β-thalassemia major: relation to cardiac complications. QJM. 2018;111(suppl_1):hcy200. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ordovas JM. Gene-diet interactions and cardiovascular diseases: Saturated and monounsaturated fat. Principles of nutrigenetics and nutrigenomics: Elsevier, Amsterdam; 2020. p. 211 – 22.

- 17.Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Businelle MS, Gallagher MW. Direct and indirect effects of false safety behaviors on cannabis use and related problems. Am J Addict. 2018;27(1):29–34. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crary SE, Buchanan GR. Vascular complications after splenectomy for hematologic disorders. Blood. 2009;114(14):2861–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-210112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asadi P, Vessal M, Khorsand M, Takhshid MA. Erythrocyte glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity and risk of gestational diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2019;18(2):533–41. doi: 10.1007/s40200-019-00464-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keshavarzi F, Rastegar M, Vessal M, Dehbidi GR, Khorsand M, Ganjkarimi AH, et al. Serum ischemia modified albumin is a possible new marker of oxidative stress in phenylketonuria. Metab Brain Dis. 2018;33(3):675–80. doi: 10.1007/s11011-017-0165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taher AT, Saliba AN. Iron overload in thalassemia: different organs at different rates. Hematology 2014, the American Society of Hematology. Education Program Book. 2017;2017(1):265–71. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coverdale JP, Katundu KG, Sobczak AI, Arya S, Blindauer CA, Stewart AJ. Ischemia-modified albumin: Crosstalk between fatty acid and cobalt binding. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2018;135:147–57. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2018.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takhshid M, Kojuri J, Tabei S, Tavasouli A, Heidary S, Tabandeh M. Early diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome with sensitive troponin I and ischemia modified albumin. 2010.

- 24.El-Farrash RA, Ismail EA, Nada AS, Hassan KY. Ischemia modified albumin levels in infants of diabetic mother: Relation to maternal glycemic control. Egypt J Pediatr. 2017;394(5961):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghergherehchi R, Habibzadeh A. Insulin resistance and β cell function in patients with β-thalassemia major. Hemoglobin. 2015;39(1):69–73. doi: 10.3109/03630269.2014.999081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soliman A, Yassin M, Al Yafei F, Al-Naimi L, Almarri N, Sabt A et al. Longitudinal study on liver functions in patients with thalassemia major before and after deferasirox (DFX) therapy. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6(1):e2014025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Amin A, Jalali S, Amin R, Aale-yasin S, Jamalian N, Karimi M. Evaluation of the serum levels of immunoglobulin and complement factors in b-thalassemia major patients in Southern Iran. Iran J Immunol. 2005;2(4):220–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanab A, El-Desouky M, Kholoussi N, El-Kamah G, Fahmi A. Evaluation of neopterin as a prognostic factor in patients with beta-thalassemia, in comparison with cytokines and immunoglobulins. Arch Hell Med/Arheia Ellenikes Iatrikes. 2015;32(1).

- 29.Ayyash H, Sirdah M. Hematological and biochemical evaluation of β-thalassemia major (βTM) patients in Gaza Strip: A cross-sectional study. Int J Health Sci. 2018;12(6):18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balci YI, Ünal S, Gümrük F. Serum lipids in Turkish patients with [Beta]-Thalassemia Major and [Beta]-Thalassemia Minor/Türk [Beta]-Talasemi Majör ve [Beta]-Talasemi Minör Hastalarinin serum lipidleri. Turk J Haematol. 2016;33(1):42. doi: 10.4274/tjh.2015.0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim HA, Zakaria SS, Elbatch MM, Ramadan M. New insight on premature atherosclerosis in Egyptian children with β-thalassemia major. 2018.

- 32.Tselepis AD, Hahalis G, Tellis CC, Papavasiliou EC, Mylona PT, Kourakli A, et al. Plasma levels of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 are increased in patients with β-thalassemia. J Lipid Res. 2010;51(11):3331–41. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M007229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arıca V, Arıca S, Özer C, Çevik M. Serum lipid values in children with beta thalassemia major. Pediatr Ther. 2012;2(5):1–3. doi: 10.4172/2161-0665.1000130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haghpanah S, Davani M, Samadi B, Ashrafi A, Karimi M. Serum lipid profiles in patients with beta-thalassemia major and intermedia in southern Iran. J Res Med Sci. 2010;15(3):150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim YE, Kim DH, Roh YK, Ju SY, Yoon YJ, Nam GE, et al. Relationship between Serum Ferritin Levels and Dyslipidemia in Korean Adolescents. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0153167. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calandra S, Bertolini S, Pes GM, Deiana L, Tarugi P, Pisciotta L et al, editors Β-thalassemia is a modifying factor of the clinical expression of familial hypercholesterolemia. Seminars in vascular medicine; 2004: Copyright© 2004 by Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc., 333 Seventh Avenue, New …. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Tangvarasittichai S, Pimanprom A, Choowet A, Tangvarasittichai O. Association of iron overload and oxidative stress with insulin resistance in transfusion-dependent beta-thalassemia major and beta-thalassemia/HbE patients. Clin Lab. 2013;59(7–8):861–8. doi: 10.7754/clin.lab.2012.120906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonuga OO, Abbiyesuku FM, Adedapo KS, Sonuga AA. Insulin resistance index and proatherogenic lipid indices in the offspring of people with diabetes. Int J Diabetes Metab. 2019;25(1–2):11–8. doi: 10.1159/000497079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Samahy MH, Tantawy AA, Adly AA, Abdelmaksoud AA, Ismail EA, Salah NY. Evaluation of continuous glucose monitoring system for detection of alterations in glucose homeostasis in pediatric patients with β‐thalassemia major. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019;20(1):65–72. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]