Abstract

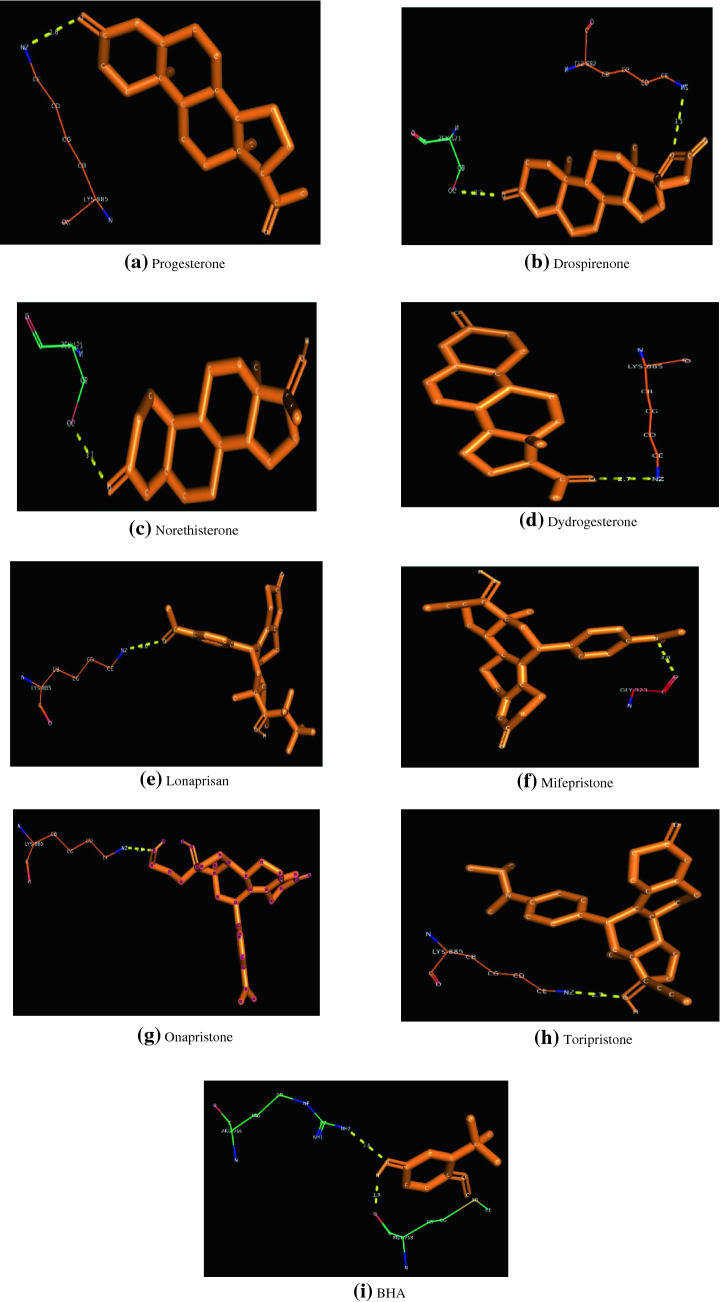

Antioxidant food additives were routinely used for increasing the keeping quality of packaged food items. Butylated Hydroxyanisole (BHA) is one of the most widely used synthetic phenolic antioxidants of such kind. Although quantity of antioxidants in packaged eatables and admissible daily intake (ADI) per person per day are limited by laws, the urbanisation and changes in lifestyle has cross these limits. Although studies on BHA has been carried out, there exists a great deal of uncertainty about the exact molecular mechanism of interaction of BHA with various receptors in the body. Since earlier reports suggested BHA plausibly interferes with reproductive system development, we opted docking of critical receptors of endogenous hormones controlling growth and development of reproductive system with BHA. Nuclear receptors of estrogen (ER), androgen (AR) and progesterone (PR) were selected for this purpose. This manuscript describes the comparison of binding pattern of BHA towards AR, ER and PR along with their agonists and antagonist. Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm of AutoDock 4.0 was used for analysing the mode of binding of ligands with the receptors. It is evident form the docking studies that, BHA exhibited similar binding pattern` with antagonists of AR and agonists of ER. But the interaction of BHA with PR was not compatible with either agonists or antagonists. The docking patterns produced could reliably demonstrate the interactions of BHA with selected receptors and also predict its possible agonistic and antagonistic action.

Keywords: Agonists, Antagonists, Antioxidant, BHA, Molecular docking

Introduction

Butylated Hydroxyanisole (BHA) is world widely accepted as a common synthetic phenolic anti-oxidant, also used as a food additive (Opinion 2011). It is an isomeric mixture of 2-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole and 3-tert-butyl-4-hydroxyanisole. It is also used as constituent for some pharmaceuticals (Iverson 1995). The admissible daily intake (ADI) of BHA is restricted to a maximum of 0.5 mg/day. There exists a chance for absorbing BHA through skin, when it is added in cosmetic formulation. They might also be absorbed during ingestion of BHA supplimented food products. It is advisable to limit BHA content below 0.02% of the total fat composition of food products. BHA has been listed to be a Category-1 priority substance by The European Commission on Endocrine Disruption since it interferers with normal hormonal function. Even though there are numerous international and national regulations, BHA is added in various cosmetic and food formulations beyond the recommended limits. Different properties and effects including carcinogenicity, antioxidant efficancy etc. are well studied. However, the extent of action caused by this substance in its molecular basis is not well understood. A very few studies reported about the endocrine disrupting properties of this compound by in vitro and in vivo experiments (Paul et al. 2018, Hwan et al. 2005). All these data available till date suggests further validation of actual endocrine disrupting properties of BHA. None of these studies described the actual molecular mechanism behind the action of the compound. Most of the available results produced contradictory results. Some studies suggested BHA as an estrogen agonist (Pop et al.2013, 2018) and in some other studies, BHA is described as an estrogen antagonists (Hwan et al. 2005). All these studies were in vivo or in vitro.

When, the results from all these available studies were cross-examined, most of them were not validated through proper channels and are addressed for further validations. These generated extreme uncertainties regarding the basic molecular mechanism behind the action of BHA. So, our group decided to re-examine the existing published works, So the present study was designed to visualise the binding of BHA with selected steroid receptors and to evaluate its agonistic and antagonistic properties using in-silico molecular docking studies. Molecular docking is a very extensively used dry lab experiment for investigating how a ligand (small molecule) binds with a receptor (large molecule). Here, we have used AutoDock 4.0 for docking studies. It is one of the most extensively used and user-friendly versions used for predicting the binding patterns of ligands with receptors. Molecular docking was carried out between BHA and AR, ER and PR (receptors critically affecting the growth and development of reproductive system). To examine whether BHA possess agonistic or antagonistic activity, endogenous hormones, synthetic agonists and antagonists of the corresponding receptors were also docked against their corresponding target molecules to visualise the possible binding of BHA. Endogenous hormone, hormone agonists and antagonists bind with the LBD but in different amino acid residues (Tamura et al. 2006). Comparison of residues at LBD will gives a clear idea about the similarity in binding patters of the various receptors selected (Fig. 1).

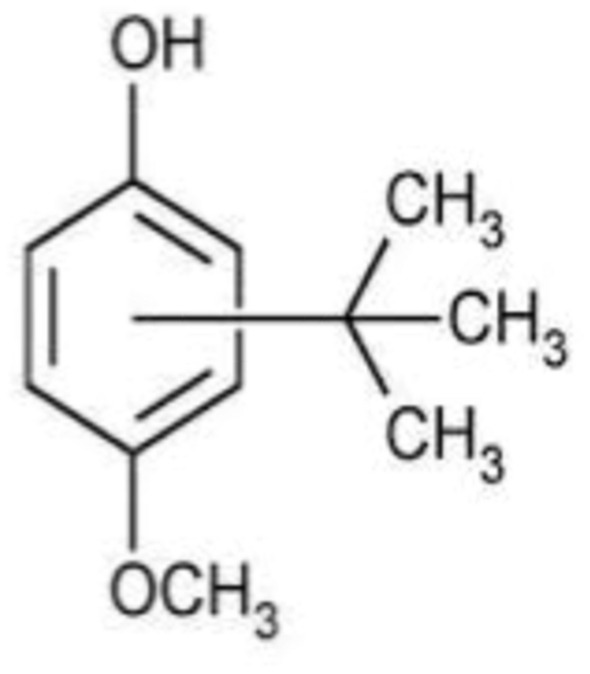

Fig. 1.

Butylated Hydroxyanisole

Materials and methods

The docking was carried out using AutoDock 4.0 (Morris et al. 1998) a very commonly used software for molecular docking. This helps in visualising hydrogen bonding (H-bond) pattern between ligand and receptor, thus helping in analysing the mode of interaction between them. The major software programmes like spdBv-Swiss-Pdb Viewer, OpenBabelGUI, Cygwin64 terminal, PyMOL, MGL tools 1.5.6 etc. were used in docking. Human Androgen Receptor (AR) (PDB id – 2AM9), Estrogen Receptor (ER) (PDB id – 1SJ0) and Progesterone Receptor (PR) (PDB id – 1A28) were obtained from protein data bank (https://www.rcsb.org/) in PDB format. Their structure is found conjugated with other compounds. All the heteroatoms and connect molecules were removed. Energy minimization of the receptors were further done using spdBv-Swiss-Pdb Viewer. The unwanted SPDV files were further removed from the.pdb files to make it suitable for docking. Three dimensional structures of endogenous agonist (natural hormones produced in the body), synthetic receptor agonist, receptor antagonists and BHA were downloaded either from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) or ChemSpider (http://www.chemspider.com/) either in.sdf or.mol format. These files were further converted into.pdb format using OpenBabelGUI version3.0.0. Basic information regarding these data is given in Table 1. For docking, MGL tools 1.5.6 was used. The receptor molecule in.pdb format is first added to the AutoDock platform. Polar hydrogens and Kollman charges were then added to facilitate proper docking. This is further saved in. pdbqt format. Ligands were also added to this platform. Root of the ligand molecule is detected to recognise the primary carbon atom. Further, it is converted to.pdbqt format. Grid Box parameters are further set to ensure proper docking. Total Grid size for AR (X = 30 Å, Y = 30 Å, Z = 30 Å) ER (X = 50 Å, Y = 50 Å, Z = 50 Å)and PR(X = 40 Å, Y = 40 Å, Z = 40 Å) and centre Grid dimension for AR (X = 27.229 Å, Y = 6.054 Å, Z = 6.114Å), ER(X = 11.139 Å, Y = 10.861 Å, Z = 9.611 Å) and PR(X = 30.282Å, Y = − 0.1.913Å, Z = 24.207Å) were assigned respectively (Joseph and Binitha 2020) (Ahirwar et al. 2016). A default Grid spacing was maintained as 0.375 Å. In this study, we have placed grid at the centre of the ligand binding domain (LBD) of the protein to ensure the proper binding of ligands at its active site. Most of the parameters are already set default accordingly to the available standard docking protocol. A total of 64,000 grid points was set on each direction. The grid output files are saved in.gpf format. Docking is further carried out using Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and files are saved in.dpf format. Both the output files are further processed using Cygwin64 terminal. Docking is done based on two separate programs, AutoDock and AutoGrid. AutoDock is concern with docking the ligand with the receptor according to the prescribed grid parameters whereas AutoGrid is involved in calculating all these grids. These files are further converted to.glg and.dlg files. Then, binding energy for the ligand and best run is obtained from rmsd (root mean square deviation) table in.dlg files. The best pose is selected based on the availability of minimum binding energy. The visualisation of docked protein in .pdb format is done by PyMOL (Python-based visualisation programme) verson2.3.3 (http://www.pymol.org). The labelling for ligands, residues, hydrogen bonds and bond distance were also visualised here.

Table 1.

Basic Information of Selected Ligands for Docking

| COMPOND NAME | CHEMICAL FORMULA | PUBCHEM CID | CHEMSPIDER ID | MOLECULAR WEIGHT (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENDOGENOUS ANDROGENS | ||||

| Testosterone | C19H28O2 | 6013 | 5791 | 288.431 |

| Dihydrotestosterone | C19H30O2 | 10,635 | 10,189 | 290.447 |

| ANDROGEN AGONIST | ||||

| Methenolone | C20H30O2 | 3,037,705 | 2,301,378 | 302.458 |

| Stanozolol | C21H32N2O | 25,249 | 23,582 | 328.49 |

| Nandrolone | C18H26O2 | 9904 | 9520 | 274.404 |

| Oxandrolone | C19H30O3 | 5878 | 5667 | 306.446 |

| ANDROGEN ANTAGONIST | ||||

| Flutamide | C11H11F3N2O3 | 3397 | 3280 | 276.212 |

| Oxendolone | C20H30O2 | 36,592 | 392,001 | 302.451 |

| Nilutamide | C12H10F3N3O4 | 4493 | 4337 | 317.224 |

| ENDOGENOUS ESTROGENS | ||||

| Estradiol | C18H24O2 | 5757 | 5554 | 272.38 |

| Estrone | C18H22O2 | 5870 | 5660 | 270.366 |

| ESTROGEN AGONIST | ||||

| Diethylstilbestrol | C18H20O2 | 448,537 | 395,306 | 268.356 |

| Mestilbol | C19H22O2 | 3,032,340 | 2,297,337 | 282.377 |

| Ethinylestradiol | C20H24O2 | 5991 | 5770 | 296.403 |

| Dienestrol | C18H18O2 | 667,476 | 580,857 | 266.334 |

| ESTROGEN ANTAGONISTS | ||||

| Fulvestrant | C32H47F5O3S | 104,741 | 94,553 | 606.78 |

| Anastrozole | C17H19N5 | 2187 | 2102 | 293.366 |

| Ethamoxytriphetol | C27H33NO3 | 6222 | 5987 | 419.55582 |

| Bilanestrant | C26H20CIFN2O2 | 56,941,241 | 35,308,225 | 446.900603 |

| ENDOGENOUS PROGESTINS | ||||

| Progesterone | C21H30O2 | 5994 | 5773 | 314.469 |

| PROGESTERONE AGONISTS | ||||

| Drospirenone | C24H30O3 | 68,873 | 62,105 | 366.501 |

| Norethisterone | C20H26O2 | 6230 | 5994 | 298.419 |

| Dydrogesterone | C21H28O2 | 9051 | 8699 | 312.446 |

| Megestrol acetate | C24H32O4 | 11,683 | 11,192 | 384.516 |

| PROGESTERONE ANTAGONISTS | ||||

| Lonaprisan | C28H29F5O3 | 6,918,548 | 5,293,745 | 508.529 |

| Mifepristone | C29H35NO2 | 55,245 | 49,889 | 429.604 |

| Onapristone | C29H39NO3 | 5,311,505 | 4,470,982 | 449.635 |

| Toripristone | C31H39NO2 | 3,086,344 | 2,342,997 | 457.658 |

| SUSPECTED ENDOCRINE DISRUPTOR | ||||

| BHA | C11H16O2 | 24,667 | 23,068 | 180.247 |

Results

Molecular docking of the selected ligands was performed with the corresponding receptors. The result of docking is available as the amount of binding energy, number of hydrogen bonds, residues interacting to form these hydrogen bonds and bond length of these hydrogen bonds. Interpretation of the bonding pattern is done by comparing the values of binding energy, bond length, number of H-bonds etc. obtained for agonists, antagonists and BHA.

Interpretations are made by analysing the following criteria.

More negative the binding energy, the more will be the force of interaction between the molecules

Bond strength increases with increase in number of H-bond

Bond strength decreases with the increase in the bond length.

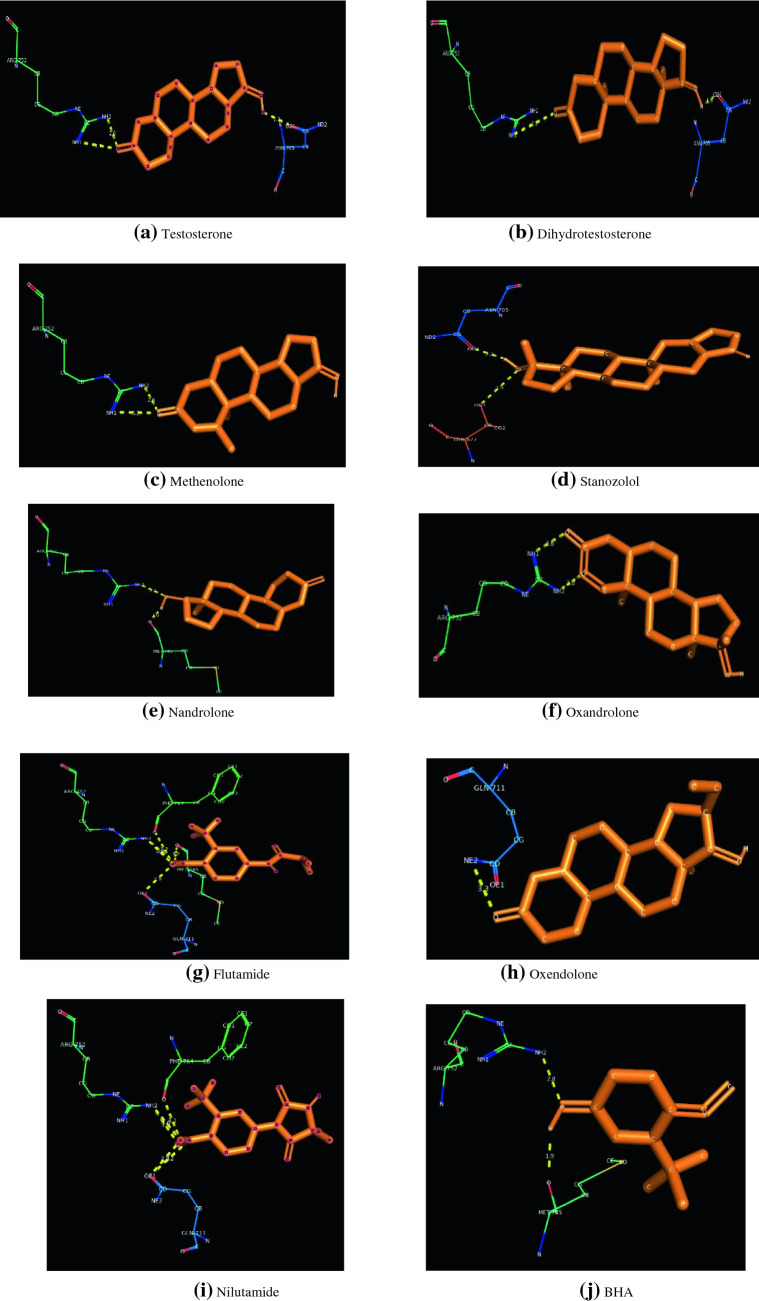

The molecular docking results of adrogen receptor with endogenous androgens (Testosterone and Dihydrotestosterone), androgen agonist (Methenolone, Nandrolone, Stanozolol, Oxandrolone), androgen antagonist (Flutamide, Oxendolone and Nilutamide) and BHA are clearly depicted in Table 2. It is clearly understood that all the selected ligands get bounded with the LBD of the ER. LBD of ER extends from residues 626–919 (Gelmann 2002).

Table 2.

Details of docking of Androgen receptor with BHA

| Compound | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Number of h bonds | Interacting residues | Bond length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENDOGENOUS ANDROGENS | ||||

| Testosterone | − 6.45 | 3 | Asparagine 705 | 2.2 |

| Arginine 752 | 2.6 | |||

| Arginine 752 | 3.1 | |||

| Dihydrotestosterone | − 8.31 | 2 | Asparagine 705 | 1.9 |

| Arginine 752 | 3.5 | |||

| ANDROGEN ANTAGONIST | ||||

| Methenolone | − 6.72 | 2 | Arginine 752 | 2.6 |

| Arginine 752 | 3.2 | |||

| Stanozolol | − 2.61 | 2 | Arginine 752 | 2.2 |

| Threonine 887 | 3.5 | |||

| Nandrolone | − 7.60 | 2 | Arginine 752 | 2.6 |

| Methionine 745 | 2.0 | |||

| Oxandrolone | − 7.04 | 2 | Arginine 752 | 2.6 |

| Arginine 752 | 2.8 | |||

| ANDROGEN ANTAGONIST | ||||

| Flutamide | − 6.30 | 5 | Glycine 711 | 2.9 |

| Methionine 745 | 3.2 | |||

| Phenylalanine 764 | 3.3 | |||

| Arginine 752 | 3.0 | |||

| Arginine 752 | 2.8 | |||

| Oxendolone | − 5.13 | 1 | Glycine 711 | 3.3 |

| Nilutamide | − 6.70 | 5 | Phenylalanine 764 | 3.1 |

| Arginine 752 | 3.0 | |||

| Arginine 752 | 3.1 | |||

| Glycine 711 | 2.8 | |||

| Glycine 711 | 3.2 | |||

| SUSPECTED ENDOCRINE DISRUPTOR | ||||

| BHA | − 6.51 | 2 | Methionine 745 | 1.9 |

| Arginine 752 | 2.8 | |||

The corresponding figures of docking is represented as Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Docking patterns of different target molecules against Androgen Receptor

The maximum binding energy is exhibited by the natural agonists Dihydrotestosterone (−8.31 kcal/mol) followed by Nandrolone (−7.60 kcal/mol), Oxandrolone (−7.04 kcal/mol), Methenolone (−6.72 kcal/mol), Nilutamide (−6.70 kcal/mol), BHA (−6.51 kcal/mol), Testosterone (−6.45 kcal/mol), Flutamide (−6.30 kcal/mol), Oxendolone (−5.13 kcal/mol) and Stanozolol (−2.61 kcal/mol). It is found that both the synthetic antagonists Flutamide [Glycine 711(2.9Å), Methionine 745(3.2 Å), Phenylalanine 764(3.3 Å), Arginine 752(3.0 Å), Arginine 752(2.8 Å)] and Nilutamide [Phenylalanine 764(3.1 Å), Arginine 752(3.0 Å), Arginine 752(3.1 Å). Glycine 711(2.8 Å), Glycine 711(3.2 Å)] exhibited a maximum of five H-bonds each whereas Oxendolone [Glycine 711(3.3 Å)], another synthetic antagonist exhibited a single H-bond. Testosterone [Asparagine 705(2.2 Å), Arginine 752(2.6 Å), Arginine 752(3.1 Å)] possessed three hydrogen bonds followed by BHA [Methionine 745(1.9 Å), Arginine 752(2.8 Å)], Methenolone [Arginine 752(2.6 Å), Arginine 752(3.2 Å)], Stanozolol [Arginine 752(3.2 Å), Threonine 887(3.5 Å)], Nandrolone [Arginine 752(2.6 Å), Methionine 745(2.0 Å)], Oxandrolone [Arginine 752(2.6 Å), Arginine 752(2.8 Å)], and Dihydrotestosterone [Asparagine 705(1.9 Å), Arginine 752(3.5 Å)] possessed a couple of hydrogen bonds.

From our studies, it is evident that Glycine 711 was found to be a common interacting residue within all the Antagonist molecules selected for docking. Asparagine 705 and Arginine 752 are found to be a common interacting residue for both the selected endogenous androgens for docking. Threonine 887 and Methionine 745 are the other important residues where synthetic agonists get bound. In addition to Glycine 711, Arginine 752 and Methionine 745, an additional residue Phenylalanine 764 is found to participate during the interaction of antagonist. When the docking data obtained is compared between agonists and antagonists of androgen with BHA, it was observed that, binding energy of BHA approximately equal to that of Testosterone (agonist) and number of H-bonds is similar to ER agonists (Dihydrotestosterone, Methenolone, Nandrolone). Methionine 745 and Arginine 752 were found to be common interacting residues between the synthetic agonist Nandrolone and BHA. So, we conclude that BHA could behave like androgen agonist in biological system.

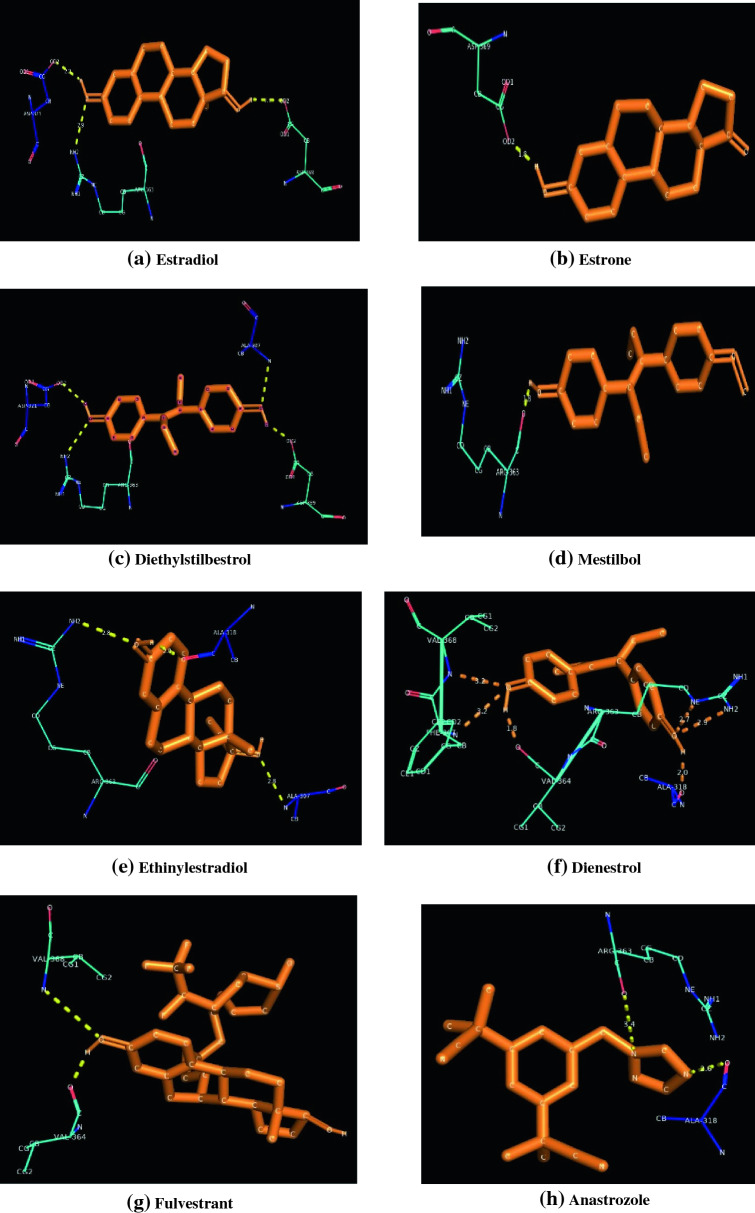

The molecular docking results of estrogen receptor with natural agonists (Estradiol and Estrone), synthetic agonists (Diethylstilbestrol, Mestilbol, Ethinylestradiol, Dienestrol), synthetic antagonists (Ethamoxytriphetol, Anastrozole, Fulvestrant,) and BHA are clearly depicted in Table 3. It is clearly understood that all the selected ligands get bounded with the LBD of the ER. LBD of ER extends from residues 302–552 (Anbalagan and Rowan 2015).

Table 3.

Details of docking of Estrogen receptor with BHA

| Compound | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Number of h bonds | Interacting residues | Bond length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENDOGENOUS ESTROGENS | ||||

| Estradiol | − 6.66 | 3 | Aspartate 321 | 2.2 |

| Arginine 363 | 2.9 | |||

| Aspartate 369 | 2.3 | |||

| Estrone | − 6.99 | 1 | Aspartate 369 | 1.8 |

| ESTROGEN AGONIST | ||||

| Diethylstilbestrol | − 5.16 | 4 | Alanine 307 | 2.8 |

| Aspartate 321 | 2.2 | |||

| Arginine 363 | 3.0 | |||

| Aspartate 369 | 2.0 | |||

| Mestilbol | − 4.39 | 1 | Arginine 363 | 1.8 |

| Ethinylestradiol | − 6.02 | 3 | Arginine 363 | 2.8 |

| Alanine 307 | 2.8 | |||

| Alanine 318 | 2.0 | |||

| Dienestrol | − 5.18 | 6 | Alanine 318 | 2.0 |

| Arginine 363 | 2.7 | |||

| Arginine 363 | 2.9 | |||

| Valine 364 | 1.8 | |||

| Phenylalanine 367 | 3.2 | |||

| Valine 368 | 3.2 | |||

| ESTROGEN ANTAGONIST | ||||

| Fulvestrant | − 3.64 | 2 | Valine 368 | 3.4 |

| Valine 364 | 1.8 | |||

| Anastrozole | − 4.85 | 2 | Alanine 318 | 2.6 |

| Arginine 363 | 3.4 | |||

| Ethamoxytriphetol | − 4.44 | 3 | Alanine 307 | 2.6 |

| Arginine 363 | 3.0 | |||

| Aspartate 369 | 1.9 | |||

| Brilanestrant | − 7.46 | 5 | Alanine 318 | 2.5 |

| Aspartate 321 | 2.5 | |||

| Leucine 308 | 3.0 | |||

| Leucine 310 | 2.7 | |||

| Leucine 310 | 2.6 | |||

| SUSPECTED ENDOCRINE DISRUPTOR | ||||

| BHA | − 4.35 | 3 | Valine 364 | 2.0 |

| Phenylalanine 367 | 3.1 | |||

| Valine 368 | 3.1 | |||

The corresponding figures of docking is represented as Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Docking patterns of different target molecules against Estrogen Receptor

It is clearly evident that, synthetic antagonist Brilanestrant exhibited the highest binding energy while Fulvestrant exhibited the lowest binding energy. Binding energies of different ligands are as follows. Brilanestrant (− 7.46 kcal/mol), followed by Estrone (− 6.99 kcal/mol), Estradiol (− 6.66 kcal/mol), Ethinylestradiol (− 6.02 kcal/mol), Dienestrol (− 5.18 kcal/mol), Diethylstilbestrol (− 5.16 kcal/mol), Anastrozole (− 4.85 kcal/mol), Ethamoxytriphetol (− 4.44 kcal/mol), Mestilbol (− 4.39 kcal/mol), BHA (− 4.35 kcal/mol) and Fulvestrant (− 3.64 kcal/mol). Synthetic agonists Dienestrol [Alanine 318(2.0 Å), Arginine 363(2.7 Å), Arginine 363(2.9 Å), Valine 364(1.8 Å), Phenylalanine 367(3.2 Å), Valine 368(3.2 Å)]possess a maximum of six hydrogen bonds followed by five hydrogen bonds for Brilanestrant[Alanine 318(2.5 Å), Aspartate 321(2.5 Å), Leucine 308(3.0 Å), Leucine 310(2.6Å), Leucine 310(2.7 Å)], four hydrogen bonds for Diethylstilbestrol[Alanine 307(2.8 Å), Aspartate 321(2.2 Å), Arginine 363(3.0 Å), Aspartate 369(2.0 Å)]. BHA[Phenylalanine 367 (3.1 Å), Valine 368 (3.1 Å), Valine 364 (2.0 Å)], Estradiol[Aspartate 321(2.2 Å), Arginine 363 (2.9 Å), Aspartate 369(2.3 Å)], Ethamoxytriphetol[Alanine 307(2.6 Å), Arginine 363(3.0 Å), Aspartate 369(1.9 Å)] and Ethinylestradiol[Arginine 363(2.8 Å), Alanine 307(2.8 Å), Alanine 318(2.0 Å)] possess three hydrogen bonds whereas Anastrozole[Alanine 318(2.6 Å), Arginine 363(3.4 Å)] and Fulvestrant[Valine 368(3.4 Å), Valine 364(1.8 Å)] possess only a pair of hydrogen bonds. Estrone [Aspartate 369 (1.8 Å)] and Mestilbol [Arginine 363(1.8 Å)] has a single hydrogen bond each.

Our results are different from the earlier available reports that suggests that Glutamate 353, Arginine 394 and Histidine 524 are found to be the major interacting residues of Estradiol and Diethylstilbestrol docked with AR (Sippl 2000). Another report also suggests that antagonists also bounds with the above cited references (Yang et al. 2010). From our studies, it is evident that Arginine 363 is found to be the common interacting residue within all the agonist molecules selected for docking expect for Estrone. Aspartate 369 is found as the common residue between both endogenous estrogen selected for docking. The three interacting residues found in BHA was similar to that in the synthetic agonist Dienestrol. So, we predict the possibility for BHA to act as an estrogenic compound in biological system. The molecular docking of Estrogen Receptor with natural agonists (Estradiol and Estrone), synthetic agonists (Diethylstilbestrol and Ethinylestradiol), synthetic antagonists (Fulvestrant and Ethamoxytriphetol) and BHA are clearly depicted in Table 3. The corresponding figures of docking is represented as Fig. 3. The maximum binding energy (-6.99 kcal/mol) is exhibited by the natural agonists Estrone whereas the minimum binding energy (− 3.64 kcal/mol) is exhibited by synthetic antagonist Fulvestrant. Another interesting observation is that binding energy of agonist were above −5 kcal/mol and antagonists were below −5 kcal/mol. The number of H-bonds varies between 1 and 4 among different ligand molecules docked against ER. No specific residues is found as a specific interacting residue common for all the seven ligands docked against ER.

When the docking data obtained was compared between agonists and antagonists of estrogen with BHA, it is observed that Valine 368 and Valine 364 are common interacting residues between BHA and Fulvestrant (antagonists). In addition. BHA also possess an additional interacting residue Phenylalanine 367, which is absent in all other docked molecules. The binding energy of BHA is approximately equal to Ethamoxytriphetol (antagonists). So, we conclude that BHA could behave like estrogen antagonists in biological system.

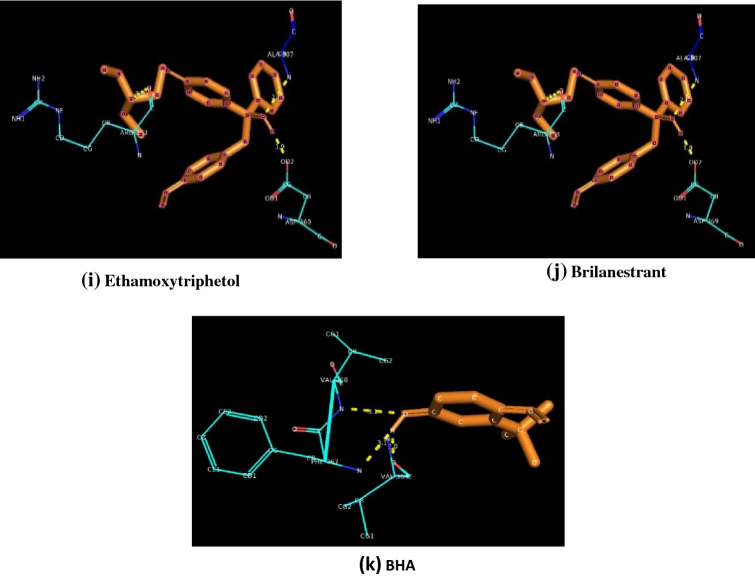

The molecular docking results of Progesterone Receptor with natural agonists (Progesterone), synthetic agonists (Drospirenone, Norethisterone, Dydrogesterone), synthetic antagonists (Mifepristone, Lonaprisan, Onapristone, Toripristone) and BHA are clearly depicted in Table 4. It is clearly understood that all the selected ligands get bounded with the LBD of the PR. LBD of PR extends from residues 687–933 (Hill et al. 2012).

Table 4.

Details of docking of Progesterone receptor with BHA

| Compound | Binding energy (kcal/mol) | Number of h bonds | Interacting residues | Bond length (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ENDOGENOUS PROGESTINS | ||||

| Progesterone | − 9.39 | 1 | Lysine 885 | 2.8 |

| PROGESTERONE AGONISTS | ||||

| Drospirenone | − 8.86 | 2 | Serine 757 | 3.3 |

| Lysine 885 | 3.2 | |||

| Norethisterone | − 9.92 | 1 | Serine 757 | 3.1 |

| Dydrogesterone | − 9.42 | 1 | Lysine 885 | 2.7 |

| PROGESTERONE ANTAGONISTS | ||||

| Lonaprisan | − 6.95 | 1 | Lysine 885 | 3.0 |

| Mifepristone | − 7.48 | 1 | Glycine 923 | 3.0 |

| Onapristone | − 7.08 | 1 | Lysine 885 | 2.8 |

| Toripristone | − 6.99 | 1 | Lysine 885 | 2.7 |

| SUSPECTED ENDOCRINE DISRUPTOR | ||||

| BHA | − 6.04 | 2 | Methionine 759 | 1.9 |

| Arginine 766 | 2.8 | |||

The corresponding figures of docking is represented as Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Docking patterns of different target molecules against Progesterone Receptor

It is clearly evident that, synthetic agonist Norethisterone exhibited the highest binding energy while BHA had lowest binding energy. Synthetic agonists Drospirenone and BHA possess two H Bonds each whereas all other docked ligands exhibited only a single H Bonds. Lysine 885 is found to be the most important interacting residue for both agonists and antagonists. But for BHA, binding to both these residues were not found. Out of different ligand molecules docked, Norethisterone exhibited the highest binding energy (− 9.92 kcal/mol), followed by Dydrogesterone (− 9.42 kcal/mol), Progesterone (− 9.39 kcal/mol), Drospirenone (− 8.86 kcal/mol), Mifepristone (− 7.48 kcal/mol), Onapristone (− 7.08 kcal/mol), Toripristone (− 6.99 kcal/mol), Lonaprisan (− 6.95 kcal/mol), BHA (−6.04 kcal/mol).

Synthetic agonists Drospirenone [Serine 757(3.3 Å) and Lysine 885 (3.2 Å)] possessed 2 hydrogen bonds whereas natural agonist Progesterone [Lysine 885(2.8Å)] and other synthetic agonists Norethisterone [Serine 757(3.1 Å)] and Dydrogesterone [Lysine 885(2.7 Å)] possess only a single hydrogen bond each. All the Synthetic Antagonists Lonaprisan [Lysine 885(3.0 Å)], Mifepristone [Glycine 923(3.0 Å)], Onapristone [Lysine 885(2.8 Å)], Toripristone [Lysine 885(2.7 Å)] possessed only a single hydrogen bond. The BHA [Methionine 759 (1.9 Å) and Arginine 766 (2.8 Å)] also possess two hydrogen bonds. The exceptional case of BHA is that the interacting residues of BHA is not seen for any other kinds of compound either agonist or antagonist. So it is unable to predict the possible role of BHA in PR at its physiological system.

Discussion

Supplementations of BHA is permitted as an antioxidant food additive and preservative in packaged food items (Opinion 2011; , 2012). Consumption of different antioxidants and food preservation are likely found to exceeded its ADI (Soubra et al. 2007). Since BHA is widely used as a food preservative in both animal and human diet, its reaches human population directly (through consumption of food items or other products rich with BHA) or indirectly (consumption of animal and animal products). Reports also suggested that different compounds which can mimic estrogen and androgen might indeed results in endocrine disruption. These compounds (including antioxidants) are also capable of causing infertility especially in males (Rashtian, Chavkin and Merhi 2019) (Carocho, Morales and Ferreira 2018). Endocrine disrupters are referred to those compounds that affects homeostasis, developmental processes and reproduction of individuals by interfering in the normal biosynthesis as well as metabolism of endogenous hormones (Diamanti-kandarakis et al. 2009). Usually, compounds having structural similarity with endogenous steroid hormones can easily act as endocrine disruptors. This is made possible by binding with cellular steroid hormone receptors (Lee et al. 2013). Most of the these chemicals possess phenolic moieties helping them to mimic endogenous steroids and thus initiating agonistic or antagonistic action (Diamanti-kandarakis et al. 2009).

Estrogenic (Pop et al. 2013, 2018), Androgenic (Schrader 2000), Anti-estrogenic (Hwan et al. 2005) and Anti-androgenic (Pop et al. 2016) (Orton et al. 2014) properties of BHA has been reported. BHA was reported to antagonise dihydrotestosterone activation of AR (Schrader 2000). Analysis of various properties of routine used personal care products composed of BHA revealed that they possess anti-androgenic properties (Orton et al. 2014). A concentration depended increase in the anti-androgenic potential of BHA has also been reported so far (Pop et al. 2016). Hershberger assay was also used to reveal the anti-androgenic activities of BHA (Hwan et al. 2005). It was observed that BHA added to invitro cultures of MCF 7 cells reduced the binding of endogenous estrogen with its receptors (Jobling et al. 1995). In a uterotrophic assay using immature female rats, Kang et.al reported that BHA exhibited anti-estrogenic properties (Hwan et al. 2005). A possibility of endocrine disruption and estrogenicity of BHA was evident by the sharp increase in the absolute and relative uterine weights in immature rats (Pop et al. 2013). Li et al. observed the downregulation of critical genes necessary for the conversion of cholesterol into its downstream components in leydig cells (Li et al. 2016). A hike in the circulating estrogen levels, reduction in sperm count and motility, reduction in gonadal size and weight are visualised when BHA is administrated in male fishes (Paul et al. 2018). A primary cell culture study with rat leyding cells reported that the activities of HSD3B1 and CYP17A1 (enzymes involved in steroidogenesis) were directly inhibited during the administration of BHA (Li et al. 2016) (Zhang et al. 2019).

Although the available literature suggested that BHA affects the reproductive system (Jeong et al. 2005), but proper evidences were not available regarding the actual mechanism behind it. Studies regarding the toxicological effects of BHA are very limited and none of these studies explained the actual chemistry behind agonistic or antagonistic action as well as its binding towards the steroid receptors. Most of the studies regarding the endocrine disrupting properties of BHA was restricted to in vitro cell line studies and a few of them were carried out using animal models due to ethical concerns. From our docking studies, we understood that BHA could behave agonistically with AR and antagonistically with ER. Some available clearly reports supported our results (Orton et al. 2014) (Pop et al. 2013, 2016, 2018).

Conclusion

The purpose of the work is to visualise the molecular binding between the selected steroid receptors (AR, ER, PR) and BHA. This binding patterns were further compared with the binding patterns of natural agonists, synthetic agonists and antagonists of the respective steroid receptors. It is clearly evident that the docking results of BHA were comparable with agonists of estrogen receptors and antagonists of androgen receptors. So, this makes a clear evidence that BHA acts both as an estrogen agonist as well as an androgen antagonist. Since agonists and antagonists binds with cellular steroid receptors, they might interfere with the natural action of endogenous hormones. In the context, BHA can act as an endocrine disruptor. We recommend to carry out a comparative docking study of BHA towards steroid receptors of different species to confirm similarities in agonistic/antagonistic properties of BHA in different species. To root out whether BHA causes endocrine disruption, multi generation reproductive assays can be useful.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge University Grands Commission (UGC) for providing JRF fellowship.

Funding

Subin Balachandran receives Junior Research Fellowship (JRF) Ref. No.:908/(CSIR-UGC NET JUNE 2018) from University Grands Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Subin Balachandran, Email: subinpbnair@gmail.com, Email: subinbalachandran@shcollege.ac.in.

R. N. Binitha, Email: binithamac@gmail.com, Email: binitharn@gmail.com

References

- Ahirwar R, et al. In silico selection of an aptamer to estrogen receptor alpha using computational docking employing estrogen response elements as aptamer-alike molecules. Berlin: Nature Publishing Group; 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anbalagan M, Rowan BG. Estrogen receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;418:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carocho M, Morales P, Ferreira ICFR. Trends in food science and technology antioxidants : reviewing the chemistry, food applications, legislation and role as preservatives’, trends in food science and technology. Elsevier. 2018;71:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL (2002) The PyMOL molecular graphics system (http://www.pymol.org)

- Diamanti-kandarakis E, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals : an endocrine. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelmann EP. Molecular biology of the androgen receptor. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(13):3001–3015. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill KK, et al. Structural and functional analysis of domains of the progesterone receptor. Mole Cell Endocrinol Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 2012;348(2):418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwan GK, et al. Evaluation of estrogenic and androgenic activity of butylated hydroxyanisole in immature female and castrated rats. Toxicology. 2005;213(1–2):147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson F. Phenolic antioxidants: Health protection branch studies on butylated hydroxyanisole. Cancer Lett. 1995;93(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03787-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SH, et al. Effects of butylated hydroxyanisole on the development and functions of reproductive system in rats. Toxicology. 2005;208(1):49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling S, et al. A variety of environmentally persistent chemicals, including some phthalate plasticizers, are weakly estrogenic. Environ Health Perspect. 1995;103(6):582–587. doi: 10.1289/ehp.95103582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph R, Binitha RN. Materials Today : Proceedings Screening of potential antiandrogenic phytoconstituents and secondary metabolites of Terminalia chebula by docking studies. Mater Today Pro Elsevier Ltd. 2020;25:316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.01.593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, et al. Molecular mechanism ( s ) of endocrine-disrupting chemicals and their potent oestrogenicity in diverse cells and tissues that express oestrogen receptors. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17(1):1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2012.01649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, et al. Effects of butylated hydroxyanisole on the steroidogenesis of rat immature Leydig cells. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2016;26(7):511–519. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2016.1202367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, et al. Automated Docking Using a Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm and an Empirical Binding Free Energy Function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19(14):1639–1662. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(19981115)19:14<1639::AID-JCC10>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Opinion S. Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of butylated hydroxyanisole – BHA (E 320) as a food. EFSA J. 2011 doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Opinion S. Scientific opinion on the re-evaluation of butylated hydroxytoluene BHT (E 321) as a food additive. EFSA J. 2012;10(3):1–43. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orton F, et al. Mixture effects at very low doses with combinations of anti-androgenic pesticides, antioxidants, industrial pollutant and chemicals used in personal care products. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;278(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul G, Binitha RN, Sunny F. Fish short-term reproductive assay for evaluating the estrogenic property of a commonly used antioxidant, butylated hydroxyanisole. Curr Sci. 2018;115(8):1584. doi: 10.18520/cs/v115/i8/1584-1587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pop A, et al. Evaluation of the possible endocrine disruptive effect of butylated hydroxyanisole, butylated hydroxytoluene and propyl gallate in immature female rats. Farmacia. 2013;61(1):202–211. [Google Scholar]

- Pop A, et al. ‘Individual and combined in vitro (anti)androgenic effects of certain food additives and cosmetic preservatives. Toxicol Vitro. 2016;32:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop A, et al. Estrogenic and anti-estrogenic activity of butylparaben, butyl- ated hydroxyanisole, butylated hydroxytoluene and propyl gal- late and their binary mixtures on two estrogen responsive cell lines. J Appl Toxicol. 2018 doi: 10.1002/jat.3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashtian J, Chavkin DE, Merhi Z. Water and soil pollution as determinant of water and food quality/contamination and its impact on female fertility. Repro Biol Endocrinol. 2019;2:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12958-018-0448-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader TJ. Examination of selected food additives and organochlorine food contaminants for androgenic activity in vitro. Toxicol Sci. 2000;53(2):278–288. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/53.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl W. Receptor-based 3D QSAR analysis of estrogen receptor ligands - merging the accuracy of receptor-based alignments with the computational efficiency of ligand-based methods. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2000;14(6):559–572. doi: 10.1023/A:1008115913787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soubra L, et al. Dietary exposure of children and teenagers to benzoates, sulphites, butylhydroxyanisol ( BHA ) and butylhydroxytoluen ( BHT ) in Beirut ( Lebanon ) Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;47:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura H, et al. Structural basis for androgen receptor agonists and antagonists: interaction of SPEED 98-listed chemicals and related compounds with the androgen receptor based on an in vitro reporter gene assay and 3D-QSAR. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14(21):7160–7174. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WH, et al. Exploring the binding features of polybrominated diphenyl ethers as estrogen receptor antagonists: docking studies. SAR QSAR Environ Res. 2010;21(3):351–367. doi: 10.1080/10629361003773971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, et al. Endocrine disruptors of inhibiting testicular 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. Chemico-Biol Interact Elsevier. 2019;303:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]