Abstract

Purpose

Diabetes mellitus is a prevalent metabolic disorder that entails numerous complications in various organs. In current era, different types of diseases are being treated by the applications of herbs. The present study is aimed at investigating the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of the Rubus fruticosus hydroethanolic extracts (RFHE) in the streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats.

Methods

At this experimental research, male Wistar rats with the weight of 220 ± 20 g, were categorized randomly into five groups of vehicles as control, STZ (60 mg kg− 1 of body weight, intraperitoneally (i.p.)) and RFHE (50, 100 and 200 mg kg− 1, i.p.). In the last stage (end of week 4) of the experiment, after being euthanized, the blood samples of the rats were collected for measuring malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH), total antioxidant status (TAS) as well as inflammatory markers like tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP).

Results

Data from this study was revealed that diabetes causes oxidative damage and consequently the serum level of inflammatory markers rises. RFHE was shown to be significantly correlated with lowering the level of MDA, TNF-α, IL-6 and CRP of diabetic rats. Moreover, RFHE significantly elevated the GSH and TAS serum levels in diabetic rats when compared with STZ group.

Conclusions

RFHE might have anti-diabetic properties; this outcome may be mediated by high antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.

Keywords: Rubus fruticosus, Antioxidant activity, Diabetes, Streptozotocin, Inflammation

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is amongst the most rampant metabolic disorders that involves many ramifications in various organs [1]. Diabetes involves hyperglycemia and impaired metabolism of carbohydrates, proteins and fats. It is very prevalent and costly chronic diseases throughout the world which its rate of prevalence is exponentially growing due to the changes in lifestyles and improvements in the health and therapeutic status of communities, which have led to increased survival rate [2]. Studies suggest that there is a significant correlation between diabetes and age, body mass index (BMI), and family history as well as gender [3]. Statistics in 1997 demonstrated that around 124 million patients were diagnosed with the disease [4]. Some of the factors that increase the risk of diabetes include: low control of blood glucose, elongated duration or even early onset of type 1 diabetes, genetic susceptibility such as smoking, physical inactivity, family history, obesity, hyperlipidemia and hypertension (excessive amounts of fat in blood) [5]. Free radicals are molecules that are chemically very active. In the metabolic reactions of the body, this radical production process in cells is natural. Typically, the radicals are eliminated from the body by antioxidant compounds and enzymes. Some antioxidant factors to be counted are glutathione (GSH), and total antioxidant status (TAS). Imbalance between the defense effect of antioxidant and increase in the production of free radicals creates a condition which is called oxidative stress. Hyperglycemia caused by diabetes increases the oxidative stress indicators like the membrane lipid peroxidation including malondialdehyde (MDA) [6]. In addition, studies have reported that DM increases inflammatory factors like tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and C-reactive protein (CRP) production [7].

Medicinal plants due to their availability, minimal side effects and more reasonable price are good alternatives for synthetic drugs, which have been of interest to researchers. Natural compounds, which are a branch of modern drug therapy, are driven from plants [8]. Raspberry plant, which has the scientific name of Rubus fruticosus L., is from the Rosaceae plant family. Raspberry plant in traditional medicine is known to be a laxative, diuretic substance, blood diluent, anti-fever and antiseptic properties. Its beneficial effects in controlling the blood pressure and strengthening the cardiac output have been proven as well [9]. It has a unique antioxidant effect; it is also rich in vitamins A, C, and prevents unwanted damages to the cell membranes and other structures in the body by neutralizing the free radicals [9]. Antioxidant properties of raspberry have been attributed to vitamin C, anthocyanins and phenolic compounds. The phenolic compounds of raspberries prevent the oxidation of low density lipoprotein (LDL) and liposomes in the body, and its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-angiogenesis and anti-cancer properties return to its polyphenols content [9, 10]. The phenolic compounds in the raspberry are protective against the metabolic diseases, obesity, cardiovascular diseases and inflammation [9, 10]. Moreover, a recent study has shown that the raspberry has a beneficial effect in learning and memory against diabetes induced by streptozotocin (STZ) in male rats [11]. Therefore, the presence of these active and effective compounds in raspberry can be beneficial in reducing the complications of diabetes.

The vast mainstream of research concerning R. fruticosus is focused on chemoprevention and anticancer effects, and few studies have been carried out to detect the protective effects of. R. fruticosus extract, particularly fruit extract, in the diabetic subjects. In this regard, given the fact the previous research has failed to properly recognize the effects of the R. fruticosus hydroethanolic extracts (RFHE) on diabetes, this study is aimed at investigating the effect of RFHE on the serum levels of GSH, TAS, MDA, CRP and inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 in the diabetic rats induced by STZ.

Materials and methods

Animals and ethical statement

In this study, 40 male Wistar rats were used which were obtained from Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran. The animals were transited to the animal room. During the project, the rats were kept at the temperature of 22 ± 2 °C and in a light condition of 12 h of darkness and 12 h of light. Furthermore, there were no restrictions in terms of food and water consumption. All the ethical considerations of working with the animals were taken into account (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition, National Academies Press). Also, the Ethics Committee of Bu-Ali Sina University, confirmed the validity of this project (IR.BASU.REC.1397.036).

Preparation of the herbal extracts

The R. fruticosus plant was adopted after being scrutinized by the Agricultural Research Center (voucher number 1036). It was transferred to a laboratory and was kept in dry and dark place. Next, about 500 g of dry plant through grinding was turned into powder with the ratio of 1 to 4 in an 80% ethanolic containing solution for two weeks. After the allotted time elapsed, the ingredients in the container were passed through paper-made filter and the elicited solution was placed in a rotary system in temperature 40 °C, with an average rotation. After condensation and solvent removal, the garnered extract was laid under a fan to become completely dried, the extract yield was about 25 g. Finally, it was taken to a -20 °C freezer until use [11].

Diabetes induction and treatments

In order to induce type 1 diabetes, STZ was used. STZ, in the present study was produced by Sigma company and it was given in a single dose (i.e. 60 mg kg− 1) intraperitoneally. The blood glucose of the rats was gauged 3 days later, using a glucometer (GlucoDr. Plus, AGM-3000, Korea). The animals which had the blood glucose level higher than 250 mg dL− 1 were deemed to have diabetes. These rats showed the symptoms of diabetes such as weight loss, polyuria and polydipsia. When it was confirmed that the rats have become diabetic, they were randomly categorized into the following five groups: (1) vehicle (control group receiving the normal saline), (2) STZ (diabetic group receiving the normal saline) and (3, 4, and 5) diabetic groups receiving RFHE at dose of 50 and doses of 100 and 200 mg kg− 1 via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, respectively for four weeks; the selection these respective doses were based on previous reports [11]. In this experiment a double blinding method was used so the experimenter was unaware about the groups’ categorization; same was done for the randomization. During the study about, 1–2 percent of the samples from each group was lost.

Blood sampling and serum isolation

After the overnight fasting in the metabolic cage, the animals were put to deep anesthesia; next, their samples of blood were gathered from their hearts directly. These samples were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min, the serums were separated.

Determination of the inflammatory markers

Estimation of IL-6, CRP and TNF-α levels were gained through a commercially accessible kit i.e. ELISA (Invitrogen ELISA Kit, Camarillo, CA) according to the manufacturer’s technique; their expressions were as follows: TNF-α by pg/mL and CRP and IL-6 by mg/L.

Determination of the antioxidant activity

The GSH levels were assessed by Ellamn’s reagent (5,50-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid) [12]. Ferric reducing antioxidant power procedure (FRAP) was used to gauge the status of antioxidant (TAS) [13]. Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) procedure was used to evaluate the serum MDA level [14].

Statistical analysis and data presentation

The elicited data from experimental groups were analyzed through GraphPad Prism version 8 software and then scrutinized through mean ± standard error from mean (SEM) method. The data went through for normality test, using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. In order to compare the results from the tests one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and then Tukey’s post hoc tests were used for the comparison amongst the groups. P < 0.05. was deemed significant for the differences in the observed data.

Results

The effect of RFHE on oxidative damage in STZ-induced diabetes

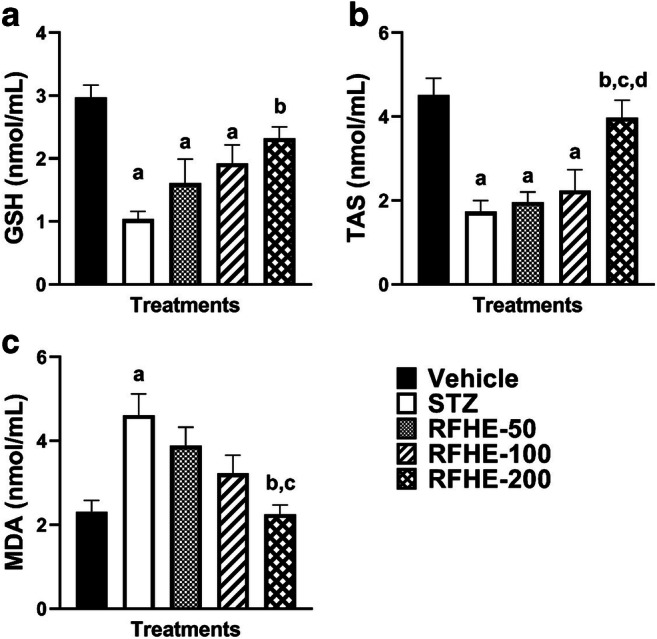

Significant differences were observed in the mean of GSH levels in the serum of the rats amongst different groups (F4,35 = 8.56, P < 0.001). The post hoc analysis suggested that in comparison to that of the vehicle group, the GSH level mean was significantly decreased in the STZ-treated groups (P < 0.001). The RFHE treatment at a dose of 200 significantly increased the mean GSH level vis-à-vis the group with STZ (P < 0.001). Conversely, the treatment with RFHE-50 and 100 failed to increase the mean serum levels of GSH compared to the STZ group (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Comparing the serum level of GSH (A), TAS (B), and MDA (C) in rats which receive the vehicle, STZ, RFHE-50, -100 and − 200. The numbers showing mean ± SEM are related to (n = 8) male Wistar rats. Small captions display the significant meaningfulness (P < 0.05) in changing the GSH, TAS, and MDA levels after the treatments. a, vs. Vehicle; b, vs. STZ; c, vs. RFHE-50; d, vs. RFHE-100. Comparing the serum level of in rats which receive the vehicle, STZ, RFHE-50, -100 and − 200

A significant mean difference in TAS of the serum was found through the analysis of variance amongst different groups (F4,35 = 11.42, P < 0.001). In comparison to that of the vehicle group, the mean serum TAS level was significantly decreased in the STZ-treated groups (P < 0.001). The RFHE treatment in dose of 200 significantly increased the mean TAS level compared to the STZ group (P < 0.001). In contrast, treatment with the RFHE-50 and − 100 failed to increase the mean serum levels of TAS compared to the STZ group (Fig. 1B).

In addition, significant differences were observed in the mean of MDA levels in the serum of the rats amongst different groups (F4,35 = 6.89, P < 0.001). The post hoc analysis suggested that in comparison with that of the vehicle group, the MDA level mean was significantly increased in the STZ-treated groups (P < 0.001). While the RFHE treatment with a dose of 200 significantly decreased the mean level of MDA in comparison to that of the STZ group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 1C), the treatment with RFHE-50 and − 100 failed to decrease the mean serum levels of MDA vis-à-vis that of the STZ group (Fig. 1C).

The impact of RFHE on the inflammatory markers in STZ-induced diabetes

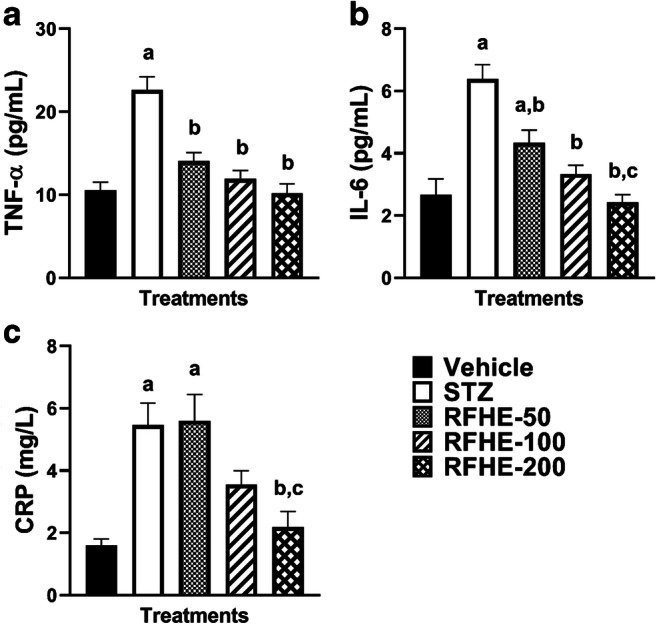

Significant differences were observed in the mean of TNF-α levels in the serum of the rats amongst different groups (F4,35 = 19.56, P < 0.001). The post hoc analysis suggested that the in comparison to that of the vehicle group, TNF-α level mean was significantly increased in the STZ-treated groups (P < 0.001). Compared to that of the STZ group, the mean of TNF-α level was decreased significantly with the RFHE treatment at doses of 50, 100 and 200 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Comparing the TNF-α (A), IL-6 (B), and CRP (C) serum levels in rats which receive the vehicle, STZ, RFHE-50, -100 and − 200. The numbers showing mean ± SEM are pertained to (n = 8) male Wistar rats. Small captions are showing the significant meaningfulness (P < 0.05) in changing the TNF-α, IL-6 and CRP levels after the treatments. a, vs. Vehicle; b, vs. STZ. b, vs. STZ; c, vs. RFHE-50

Through the analysis of variance, the mean of IL-6 of the serum amongst different groups was demonstrated to be significantly different (F4,35 = 16.86, P < 0.001). In comparison to that of the vehicle group, the mean serum IL-6 level was significantly increased in the STZ-treated groups (P < 0.001).The RFHE treatment in doses of 50, 100, and 200 significantly decreased the mean IL-6 level compared to the group of STZ (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2B).

Significant differences were observed in the mean of CRP levels in the serum of the rats amongst the groups (F4,35 = 9.93, P < 0.001). The post hoc analysis revealed that in comparison to that of the vehicle group, the CRP level mean was significantly increased in the STZ-treated groups (P < 0.001). The RFHE treatment in dose of 200 significantly decreased the mean CRP level vis-à-vis that of the STZ group (P < 0.001). Conversely, treatment with RFHE-50 and 100 failed to decrease the mean serum levels of CRP compared to the STZ group (Fig. 2C).

Discussion

The findings of the present research unveil that the IP injection of RFHE has significantly meaningful and positive effects on the rats’ antioxidant and inflammatory statue. As it was mentioned above, RFHE, with different dose levels, reduces IL-6, TNF-α, MDA and CRP and increase the levels of GSH and TAS in the diabetic rats very significantly. Previous research has reported that the hyperglycemic conditions, oxidative stress and inflammatory damages cause diabetes. Patients with diabetes succumb to oxidative stress more than ordinary individuals [15–17].

While the production of free radicals in diabetic patients increases, their antioxidant boosting decreases. This, consequently leads to their oxidative stress level going up [18]. Induced diabetes in the rats decreased their activity of GSH and TAS in the group. Long-term diabetes leads to increased MDA. In addition, as a result of oxidative stress, and the subsequent increase in TNF-α, IL-6 and CRP, complications of diabetes are caused [19, 20]. R. fruticosus in the traditional medicine is applied as a supplementary nutrient. The analyses show that RFHE reduces the free radicals [21, 22]. They also display the antioxidant, antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects of the herb [9, 10, 23]. RFHE, having multiple phenolic ingredients with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, might diminish oxidative stress caused by diabetes. In 2015, Caidan et al. reported that Rubus species have strong antioxidant ingredients [22]. It seemed that flavonoid content and phenolic compounds in raspberry fruit extract played a significant role in reversing the pathological alterations observed in diabetic rats. The long-term administration of flavonoid-rich extracts in diabetic rats has been reported to reduce serum MDA level [24]. As of yet, however, there seems to be no available literature on the impacts of raspberry fruit extract on GSH, MDA and TAS activity in the models of the diabetic animals.

The present study revealed that based on a chosen dose level, RFHE could significantly influence diabetes and stop the increase of inflammatory markers in the male Wistar rats that became diabetic through the induction of STZ.The results of the present study demonstrate the effects of STZ on the inflammatory markers like IL-6, CRP, and TNF-α as well as the elevation of these markers in the experimental model. Moreover, the statistical results revealed that the treatment with RFHE decreases the inflammatory marker. These effects may be due to the antioxidant property of RFHE and enzymatic mechanisms. The current findings are aligned with those of Jean-Gilles and colleagues (2012) that demonstrated the anti-inflammatory impact of the polyphenolic-enriched red raspberry extract on the arthritis rats which were induced by antigen. This study demonstrated that the amount of hind limb edema, increases in the antigen-induced arthritis rats. In this study, 120 mg kg− 1 of the extract of red raspberry enriched by polyphenol was found to reduce the resorption of the bone, formation of pannus, damage to cartilage as well as inflammation thanks to its antioxidant properties [25]. The present findings are also consistent with those of Sangiovanni et al. (2013) which showed that the ellagitannins from R. idaeus L. and R. fruticosus L. have anti-inflammatory impacts on the gastric lesions of the rat model induced by ethanol. This study demonstrated that the ellagitannins of R. fruticosus L. and R. idaeus L. resulted in the decrease of Ulcer Index (by 88 percent and 75 percent, respectively) and were protective against the oxidative stress of the rats induced by ethanol. Furthermore, the findings showed that the ellagitannins had inhibitory effects on the secretion of IL-8 induced by low-concentrated IL-1β and TNF-α [26]. It may be concluded that RFHE may be able to maintain the inflammatory marker TNF-α and IL-6 through its antioxidant effect and elimination of free radicals, thereby affecting the complication of DM. This study was limited to the acute induction of diabetes with STZ. It is suggested that in future studies, chronic induction with STZ or other models of diabetes induction be investigated.

Conclusions

To sum up, the results of the current research indicate that adopting RFHE may decrease the inflammation in the diabetic rats due to the natural active ingredients by strengthening the antioxidative system.

Funding

The authors have declared that there were no funding received for this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors wish to declare that there were no competing interests.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All the ethical considerations of working with the animals were accounted for (Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition, National Academies Press). Furthermore, the Ethics Committee of Bu-Ali Sina University, confirmed the validity of this project (IR.BASU.REC.1397.036).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Taheri E, Saedisomeolia A, Djalali M, Qorbani M, Madani Civi M. The relationship between serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D concentration and obesity in type 2 diabetic patients and healthy subjects. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2012;11(1):16-. doi: 10.1186/2251-6581-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larejani B, Zahedi F. Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus in Iran. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2001;1(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meraci M, Feizi A, Bagher Nejad M. Investigating the prevalence of high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes mellitus and related risk factors according to a large general study in Isfahan- using multivariate logistic regression model. Health Syst Res. 2012;8(2).

- 4.Amos AF, McCarty DJ, Zimmet P. The rising global burden of diabetes and its complications: estimates and projections to the year 2010. Diabetic Med. 1997;14(Suppl 5):1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daneman D. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2006;367(9513):847–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rains JL, Jain SK. Oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(5):567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.King GL. The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetes and its complications. J Periodontol. 2008;79(8 Suppl):1527–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohajeri D, Doustar Y, Rezaei A, Mesgari Abbasi M. Hepatoprotective Effect of ethanolic extract of Crocus sativus L. (saffron) stigma in comparison with silymarin against rifampin induced hepatotoxicity in rats. Zahedan J Res Med Sci. 2011;12:53–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zia-Ul-Haq M, Riaz M, De Feo V, Jaafar HZ, Moga M. Rubus fruticosus L.: constituents, biological activities and health related uses. Molecules. 2014;19(8):10998–1029. doi: 10.3390/molecules190810998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monforte MT, Smeriglio A, Germanò MP, Pergolizzi S, Circosta C, Galati EM. Evaluation of antioxidant, antiinflammatory, and gastroprotective properties of Rubus fruticosus L. fruit juice. Phytother Res. 2018;32(7):1404–14. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomar A, Hosseini A, Mirazi N. Preventive effect of Rubus fruticosus on learning and memory impairment in an experimental model of diabetic neuropathy in male rats. Pharma Nutr. 2014;2(4):155–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med. 1963;61:882–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budin SB, Othman F, Louis SR, Bakar MA, Das S, Mohamed J. The effects of palm oil tocotrienol-rich fraction supplementation on biochemical parameters, oxidative stress and the vascular wall of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Clinics. 2009;64(3):235–44. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322009000300015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biswas D, Banerjee M, Sen G, Das JK, Banerjee A, Sau TJ, et al. Mechanism of erythrocyte death in human population exposed to arsenic through drinking water. Toxicol Appl Pharmcol. 2008;230(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yagihashi S, Yamagishi S-I, Wada R. Pathology and pathogenetic mechanisms of diabetic neuropathy: correlation with clinical signs and symptoms. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(Suppl 1):184-S9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2007.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calcutt NA, Freshwater JD, Mizisin AP. Prevention of sensory disorders in diabetic Sprague-Dawley rats by aldose reductase inhibition or treatment with ciliary neurotrophic factor. Diabetologia. 2004;47(4):718–24. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyer F, Vidot JB, Dubourg AG, Rondeau P, Essop MF, Bourdon E. Oxidative stress and adipocyte biology: focus on the role of AGEs. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:534873. doi: 10.1155/2015/534873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasaoglu H, Sancak B, Bukan N. Lipid peroxidation and resistance to oxidation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2004;203(3):211–8. doi: 10.1620/tjem.203.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rehman K, Akash MSH. Mechanism of generation of oxidative stress and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus: How are they interlinked? J Cell Biochem. 2017;118(11):3577–85. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Domingueti CP, Dusse LMSA, Carvalho MdG, de Sousa LP, Gomes KB, Fernandes AP. Diabetes mellitus: The linkage between oxidative stress, inflammation, hypercoagulability and vascular complications. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;30(4):738–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma H, Johnson SL, Liu W, DaSilva NA, Meschwitz S, Dain JA, et al. Evaluation of polyphenol anthocyanin-enriched extracts of blackberry, black raspberry, blueberry, cranberry, red raspberry, and strawberry for free radical scavenging, reactive carbonyl species trapping, anti-glycation, anti-β-amyloid aggregation, and microglial neuroprotective effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(2):461. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caidan R, Cairang L, Pengcuo J, Tong L. Comparison of compounds of three Rubus species and their antioxidant activity. Drug Discov Ther. 2015;9(6):391–6. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2015.01179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abdu D, Majeed SNJJAC. Identification of antioxidant compounds in red raspberry (Rubus idaeus) fruit in Kurdistan region (North Iraq). 2012;2(3):6–10.

- 24.Abdel-Rahman RF, Soliman GA, Saeedan AS, Ogaly HA, Abd-Elsalam RM, Alqasoumi SI, et al. Molecular and biochemical monitoring of the possible herb-drug interaction between Momordica charantia extract and glibenclamide in diabetic rats. Saudi Pharm J. 2019;27(6):803–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jean-Gilles D, Li L, Ma H, Yuan T, Chichester CO, III, Seeram NP. Anti-inflammatory effects of polyphenolic-enriched red raspberry extract in an antigen-induced arthritis rat model. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(23):5755–62. doi: 10.1021/jf203456w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sangiovanni E, Vrhovsek U, Rossoni G, Colombo E, Brunelli C, Brembati L, et al. Ellagitannins from Rubus berries for the control of gastric inflammation: in vitro and in vivo studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]