Abstract

Purpose

The pharmacological treatment for Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is continuous and adherence to medication is critical for disease control. Restricted access to medicines is one of the most important barriers to adherence to T2DM treatment. This study aimed to evaluate other factors for medication non-adherence by studying patients with full access to oral hypoglycemic agents.

Methods

Cross-sectional study with 300 patients receiving their medication without costs from a referral center for diabetes care in Crato, Ceará (Brazil). Participants were recruited from January to December 2017. Information was obtained by self-applied questionnaires, and the drugs used were confirmed in the prescription. Adherence to medication was determined by the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4). Patient perceptions of drugs were assessed by the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ).

Results

Only 22.7% of participants met the criterion of high adherence to medication. The most frequent characteristics in the low adherence group were married; hypertension; no regular physical activity; therapy based on the combination of two or more oral antidiabetic agents without insulin; low score in the BMQ necessity scale. Necessity score in BMQ increased with age and the number of medications used and decreased if the patient had family members with the same disease and had children.

Conclusions

Full access to medicines did not assure high adherence to pharmacological treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Distinctive factors to medication non-adherence may be found and specific barriers should be considered when planning actions for improving adherence in such populations.

Keywords: Medication adherence; Diabetes mellitus, type 2; Oral hypoglycemic agents; Primary health care

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, a metabolic disease characterized by the inability to maintain blood glucose homeostasis, affects 451 million adults worldwide. It is estimated a 50% increase in this number by 2045, overcoming the projected population growth over the same period [1]. People living with diabetes suffer from injuries and sequelae that place the disease among the top 10 global causes of disability [2]. In addition, about 5 million deaths per year can be attributed to diabetes [1]. The high morbidity and mortality of this chronic condition are primarily related to long-term complications, vascular problems triggered by persistent hyperglycemia. Diabetic complications include coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, renal disease, peripheral angiopathy and retinopathy [3].

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common form of diabetes, accounting for over 90% of cases. The strong association with obesity justifies such a high occurrence. The sedentary way of life and inadequate eating habits from contemporary society promote excessive weight gain and, consequently, the development of T2DM [3]. Management of T2DM involves lifestyle change (more physical activity, weight loss, diet control and smoking cessation) and pharmacological therapy for metabolism improvement [4]. In most cases, the treatment for T2DM only controls the disease and there´s no perspective for a cure. For this reason, the patient must sustain the new lifestyle for long term and continuously use antidiabetic drugs. It is critical that patients do their part in the therapy, including adhering to medication, to reduce or delay diabetes complications.

Medication adherence is the observance by the patient of the adequate timing, dosage, and frequency of use for the prescribed medicines. It depends on the understanding of the health condition and the cooperation with the health care provider [5]. The importance of medication adherence has long been acknowledged; however, it was poorly detected in the clinical setting and insufficiently studied until 50 years ago. The concept was initially introduced as “compliance with therapeutic regimen”. It evolved to “adherence to medication” to reckon a more active role for the patient [6]. Later, it was recognized that many reasons for non-adherence are indeed intentional, but unintentional causes also have a contribution [7]. Applying the medication adherence concept is a sensitive matter. Detecting and fighting non-adherence is necessary for improving treatment. On the other side, stigmatizing patients as non-adherent does not help raising the adherence rate [5].

In T2DM, several studies show that interruption or intermittent use of medication and carelessness with the time of administration result in negative consequences for patient health [8]. In addition, non-adherence to antidiabetic pharmacotherapy is associated with increased costs to the health system [9].

The proportion of diabetic patients who correctly follow the prescribed therapy for oral hypoglycemic agents vary widely. Depending on the population studied, the treatment regimen, and the measuring method, the high adherence group may represent from 38.5 to 93.1% of patients [10]. Several features modify the degree of medication adherence in patients with T2DM. The most consistent barriers to adherence to the treatment of this disease are related to the patient (depression, understanding of the disease and treatment), the treatment itself (occurrence of adverse reactions, the complexity of therapy) and the health system (difficulty in access and high cost of medicines) [11].

An important model for understanding obstacles to patient compliance and their perception of treatment is the Necessity-Concerns Framework [12]. This theoretical matrix considers that the patient’s decision to adhere to pharmacological treatment depends on the balance between the feeling of drug dependence (Necessity) and the fear of the consequences related to its use (Concerns). The Necessity-Concerns Framework has proven to be useful in suggesting reasons for non-adherence to medication [13, 14].

Identifying non-adherence factors that are related to the T2DM patient and treatment is essential for planning and optimizing health promotion and education interventions, as well as proposing measures for preventing treatment abandonment. Indeed, recognizing patient specificities, emphasizing their knowledge of the disease and treatment, and encouraging self-care are key components of current guidelines for T2DM therapy [4].

The unavailability or impossibility of acquiring drugs in many situations is decisive for reducing treatment adherence by patients. In this sense, a particular scenario in Brazil deserves special attention. A recent population survey in the country suggests that people living with T2DM have access to medicines that, in most cases (70.7%), are obtained without costs [15]. For Brazilians living with T2DM who receive their medication from the public system, other barriers to adherence - especially related to patient and treatment - could have more noticeable influence. This study aimed to evaluate factors for medication non-adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus with full access to oral hypoglycemic agents.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study conducted in a health care unit located in Crato, a city with about 135,000 inhabitants [16], located south of the state of Ceará, northeastern Brazil. This municipality accounts for the largest territorial extension of the Cariri Metropolitan Region, the second-most populous urban region in the state.

The sample consisted of patients with T2DM, of both sexes, over 18 years old, using at least one oral hypoglycemic agent provided free of charge by the public health system. The use of injectable insulin in addition to oral agents was not an exclusion criterion. Individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus, pregnant women and patients on hemodialysis or cancer treatment were not included in the study.

The participants were recruited at the Centro de Saúde Teodorico Teles, the referral service for diabetes mellitus and/or hypertension. This health center provides care for residents of Crato referred by the primary care network or living in regions not covered by Family Health teams. It comprises a pharmacy that delivers medicines at no cost for diabetes mellitus and hypertension. The available oral hypoglycemic agents are metformin, gliclazide and glibenclamide. Every day, on average, 25 patients receive their medication at this pharmacy, reaching nearly 600 visits per month. Regarding the outpatient service, 704 registered patients in the facility attend at least four annual medical consultations. The sample size was not calculated. The study sample consisted of 300 participants selected by convenience among the registered patients.

Data collection was performed from January to December 2017. Patients on the way to get their medicines were invited to participate. In the first six months, patients were approached in the morning for three days a week. In the last six months, recruitment was intensified, occurring five days a week either in the morning or the afternoon. During data collection, 327 patients were contacted. Seven patients refused to participate, claiming lack of time. Those who agreed to participate were directed to a private room at the facility where they filled three forms. All forms were self-applied. One researcher was present, available for assistance. At the end of data collection, twenty patients were excluded because they had type 1 diabetes mellitus. Thus, the final sample comprised 300 participants.

The first form filled by the participants included information related to sociodemographic, health and pharmacotherapy aspects. The sociodemographic variables were sex, age, marital status (married, single, widowed or divorced), number of children, monthly family income (in number of minimum wages) and education (number of years attending school). Regarding health aspects, the variables were: time in years since the diagnosis of diabetes, chronic complications (including amputations, and vision, heart, circulatory and renal problems), comorbidities (hypertension, asthma, osteoporosis, dyslipidemia or others), the occurrence of diabetes in the family; regular practice of physical activity (at least 30 min per day or 3.5 h per week), use of alcohol and smoking (regardless of frequency). Concerning pharmacological therapy, participants informed which medications were prescribed for diabetes control (metformin, gliclazide, glibenclamide or others). Pharmacological treatment of T2DM was considered as monotherapy when the use of metformin alone or one sulphonylurea (gliclazide or glibenclamide) was verified. When two or more medicines were used to control diabetes, therapy was considered as drug association. In some analyzes, drug associations were subdivided according to whether or not insulin was included in therapy. Patients also reported medications being used to treat conditions other than T2DM. The information provided by the participant regarding their pharmacological treatment was confirmed by the researcher in the prescription. There was no disagreement between the information provided by the patients and the prescription concerning T2DM therapy. Medications informed by the patient that were not listed in the prescription were considered non-prescribed. Non-prescribed drugs were classified as prescription or over-the-counter drugs according to Brazilian regulations.

The second form assessed adherence to pharmacological treatment. It was the 4-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4) proposed by Morisky et al. [17] and translated into Portuguese by Ben et al. [18]. MMAS-4 includes four questions with dichotomous answers (yes/no) evaluating situations of interruption or intermittent use of medication. Each positive answer receives one point. Patients with the minimum score (0 points) were considered to have high adherence to treatment, those with 1 point or more were considered to have low adherence.

The third form evaluated patient feelings about medications. It was the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) [12] translated into Portuguese and validated by Salgado et al. [19]. This questionnaire is divided into scale N (Necessity) containing 5 items and scale C (Concerns) containing 6 items. Each item is scored on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 point for “strongly disagree” to 5 points for “completely agree”. The scores for the N and C scales are calculated by adding the points for the corresponding items. Therefore, the N scale ranges from 5 to 25 points and the C scale, from 6 to 30 points. The higher the score, the greater the patient’s belief in the respective idea. The difference between the scores for N scale and the C scale (N-C index) indicates the predominance of needs over concerns and may represent a lower risk of patients intentionally abandoning treatment [12]. Using the mean points of the N (12.5 points) and C (15 points) scales as a reference, participants were classified into four attitude groups according to their responses to the BMQ: skeptical (low necessity and high concerns), ambivalent (high necessity and high concerns), indifferent (low necessity and low concerns) or accepting (high necessity and low concerns) [20, 21].

Descriptive data were presented by absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables, and by medians and 25 and 75% percentiles, respectively. Chi-square test was used to analyze the association between qualitative variables, and Yates correction was used for variables with expected frequencies below 5. Non-parametric tests were used for data with no adherence to the normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk, p < 0.05). The Mann-Whitney test and interquartile regression were used to assess the associations of the variables studied in the necessity (N) and concern (C) scores. The interquartile regression used a stepwise backward strategy, considering the entrance criteria of p < 0.20 and the exclusion criteria of p > 0.05. The confidence level was 5%. The software used was Stata® (StataCorp, LC) version 11.0.

Results

The characteristics of the 300 patients included in the study are shown in Table 1. Participants were predominantly female (64.3%), married (69.7%) and had children (91.7%). Most studied 8 years or less (65.0%) and had low family monthly income, up to one minimum wage (65.0%). Only 40.3% reported practicing regular physical activity. The frequencies of smokers and individuals who consume alcohol were 14.7% and 19.7%, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics from the patients and the disease and association with adherence to pharmacological treatment

| Variables | Total (n = 300) |

Low Adherence (n = 232) | High Adherence (n = 68) |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 193 (64.3%) | 144 (62.1%) | 49 (72.1%) | 0.130 |

| Male | 107 (35.7%) | 88 (37.9%) | 19 (27.9%) | ||

| Age (years) | 61 (51.5–68.0) | 60 (58.0–62.0) | 64 (58.0–66.6) | 0.193 | |

| Married | 209 (69.7%) | 170 (73.3%) | 39 (57.4%) | 0.012 | |

| Had at least one child | 257 (85.7%) | 199 (85.8%) | 58 (85.3%) | 0.921 | |

| Monthly family income | Up to 1 MW | 195 (65.0%) | 150 (64.7%) | 45 (66.2%) | 0.957 |

| 1–2 MW | 76 (25.3%) | 60 (25.9%) | 16 (23.5%) | ||

| 2–3 MW | 19 (6.3%) | 14 (6.0%) | 5 (7.4%) | ||

| More than 3 MW | 10 (3.3%) | 8 (3.5%) | 2 (2.9%) | ||

| Education | 0 years | 32 (10.7%) | 24 (10.3%) | 8 (11.8%) | 0.704 |

| Up to 8 years | 195 (65.0%) | 149 (64.2%) | 46 (67.7%) | ||

| More than 8 anos | 73 (24.3%) | 59 (25.4%) | 14 (20.6%) | ||

| Regular physical activity | 121 (40,3%) | 85 (36.6%) | 36 (52.9%) | 0.016 | |

| Smoking | 44 (14.7%) | 34 (14.7%) | 10 (14.7%) | 0.992 | |

| Use of alcohol | 59 (19.7%) | 44 (19.0%) | 15 (22.1%) | 0.573 | |

| Diabetes in family | 246 (82.0%) | 195 (84.1%) | 51 (75.0%) | 0.088 | |

| Time of T2DM (years) | 7 (4.0–13.0) | 8 (6.6–8.0) | 5 (4.0–8.6) | 0.083 | |

| Number of chronic complications | 0 | 130 (43.3%) | 101 (43.5%) | 29 (42.6%) | 0.858 |

| 1–2 | 158 (52.7%) | 121 (52.1%) | 37 (54.4%) | ||

| 3 or more | 12 (4.0%) | 10 (4.3%) | 2 (2.9%) | ||

| Comorbidities | none | 82 (27.3%) | 59 (25.4%) | 23 (33.8%) | 0.172 |

| hypertension | 190 (63.3%) | 156 (67.2%) | 34 (50.0%) | 0.009 | |

| osteoporosis | 47 (15.7%) | 33 (14.2%) | 14 (20.6%) | 0.204 | |

| dyslipidemia | 78 (26.0%) | 64 (27.6%) | 14 (20.6%) | 0.247 | |

| asthma | 5 (1.7%) | 3 (1.3%) | 2 (2.9%) | 0.351 | |

Values presented as n (%) or median (p25 – p75).

Abbreviations: T2DM – Type 2 Diabetes mellitus; MW – Minimum wage.

*Chi-square

Regarding T2DM, there were patients whose diagnosis of the disease occurred from less than one year to 48 years, and the median was 7 years. About half (52.7%) mentioned one or two chronic complications. Hypertension was the most frequent comorbidity, with 63.3%. More than 80% reported that family members also had diabetes.

Only 68 of the 300 participants (22.7%) met the criterion of high adherence to pharmacological treatment by MMAS-4. The association between adherence to treatment and the patient or disease variables was studied (Table 1). Being married and having hypertension were associated with lower adherence to treatment (respectively p = 0.012 and p = 0.009). The practice of physical activity was associated with high adherence to treatment (p = 0.016). The other variables did not present a significant correlation.

The use of medications by participants is shown in Table 2. The total number of medications prescribed ranged from 1 to 13, with a median of 3 medications. For the treatment of diabetes, the most common treatment regimen (46.0%) was the drug association without insulin: metformin and at least one sulphonylurea (gliclazide or glibenclamide). The proportion of patients using insulin in addition to oral drugs was small (16.7%). Almost half of the participants (46.7%) mentioned the use of medication that the researcher did not find in the prescription. In all these 140 cases of self-medication with a non-prescribed drug, the patient reported only one medication absent in the prescription. For most of the cases, it was an over-the-counter drug. However, for 19 patients, the non-prescribed drug should only be used with a prescription according to Brazilian regulations.

Table 2.

Characteristics from the pharmacotherapy and association with adherence to pharmacological treatment

| Variables | Total (n = 300) |

Low Adherence (n = 232) | High Adherence (n = 68) |

p* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of prescribed medicines | 3 (2.0–5.0) | 3.5 (3.0–4.0) | 3 (2.0–4.0) | 0.369 | |

| antidiabetic therapy | metformin | 90 (30.0%) | 61 (26.3%) | 29 (42.6%) | 0.014 |

| sulphonylurea** | 22 (7.3%) | 20 (8.6%) | 2 (2.9%) | ||

| association without insulin | 138 (46.0%) | 115 (49.5%) | 23 (33.8%) | ||

| association with insulin | 50 (16.7%) | 36 (15.5%) | 14 (20.6%) | ||

| non-prescribed drugs | total | 140 (46.7%) | 102 (44.0%) | 38 (55.9%) | 0.083 |

| over-the-counter drugs | 121 (40.3%) | 88 (37.9%) | 33 (48.5%) | 0.090 | |

| prescription drugs | 19 (6.3%) | 14 (6.0%) | 5 (7.4%) | 0.432 | |

Values presented as n (%) or median (p25 – p75)

*Chi-square for qualitative variables and Mann-Whitney for quantitative variables

** gliclazide or glibenclamide

The pharmacotherapy for T2DM was also studied in relation to treatment adherence (Table 2). Patients using metformin alone or in association with insulin had higher adherence compared to other therapeutic regimens (p = 0.014). There was no correlation between adherence and the number of prescribed drugs or self-medication with unprescribed drugs.

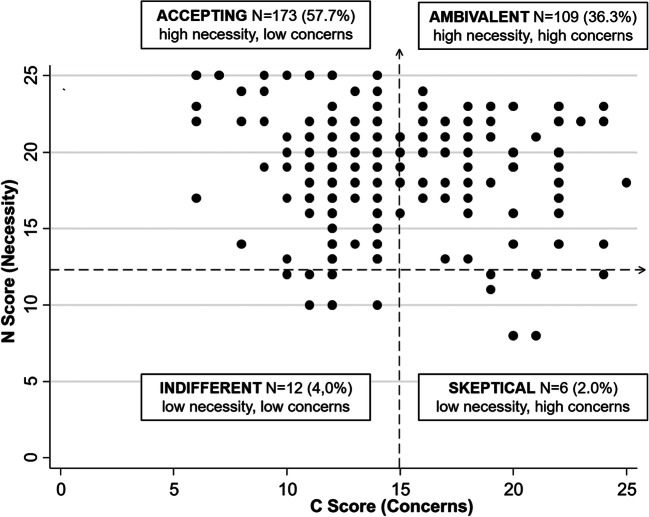

Based on the BMQ instrument scores, participants were classified into four attitudinal groups regarding medications: skeptical, ambivalent, indifferent and accepting (Fig. 1). Most patients were in groups with necessity above the midpoint: accepting (57.7%) and ambivalent (36.6%). When comparing the distribution of patients with high and low adherence among the four attitudinal groups, no statistical difference was observed.

Fig. 1.

Distribution chart of participants in attitudinal groups regarding beliefs about medicines. The boxes show the number of patients in each group and their percentages

Between the groups of high and low adherence, there was a difference for some of the scores calculated from the BMQ instrument (Table 3). The high adherence group had N score (necessity) and the N-C index (the difference between necessity and concerns scales) higher than the low adherence group (respectively, p = 0.002 and p = 0.038). The C score (concerns) was similar between the two groups.

Table 3.

Necessity (N) and Concerns (C) scores from Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) adherence to pharmacological treatment

| Variables | Total (n = 300) |

Low Adherence (n = 232) | High Adherence (n = 68) |

p* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N score | 19 (17.0–21.0) | 19 (19.0–20.0) | 20 (20.0–21.0) | 0.002 |

| C score | 13 (12.0–17.0) | 13 (12.0–14.0) | 13 (12.0–15.6) | 0.729 |

| N-C index | 5 (1.0–8.0) | 4 (3.6–5.0) | 5 (4.0–8.0) | 0.038 |

Values presented as median (p25 – p75).

* Mann-Whitney

Regarding the feeling of necessity for the drug, it was found that seven variables allow the creation of a mathematical model for the scoring of the N scale (Table 4). For four of these variables, the contribution was statistically significant. Contributed to increase the necessity score: more prescribed drugs and older age. On the other hand, the variables that reduced the value of the necessity score were having diabetes in the family and having children.

Table 4.

Mathematical model for scoring N (necessity) scale in Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ)

| Variable | Coefficient | 95% CI* | p** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| positive association | sex | 0.52 | -0.19–1.22 | 0.150 |

| number of prescribed medicines | 0.17 | 0.02–0.33 | 0.032 | |

| age | 0.03 | 0.00–0.06 | 0.035 | |

| negative association | diabetes in family | -1.77 | -2.66 – -0.87 | < 0.001 |

| children | -1.36 | -2.36 – -0.36 | 0.008 | |

| other chronic diseases | -0.69 | -1.53–0.16 | 0.111 | |

| monotherapy/association | -0.63 | -1.34–0.09 | 0.086 |

*Confidence Intervals, **Interquartile regression (R² = 0,069).

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate factors that contribute to non-adherence to T2DM treatment among patients receiving their oral hypoglycemic agents from the public health system at no cost. In this context, it was considered that aspects related to failure to comply with pharmacological therapy would be mainly related to the patient or the therapy. We evaluated 300 patients at the moment of receiving their medications.

The high adherence group to medication represented only 22.7% of the sample studied. The adherence rate observed was low, below the range of 38.5 to 93.1% found among various international studies [10]. This variability between different surveys arises in part from the choice of determination method. Most studies use questionnaires applied to patients about the use of medications. These self-reports are convenient tools for rapid assessment of adherence. Questionnaires also have the potential to measure medication-taking behavior and identify barriers and beliefs associated with non-adherence [22, 23]. Some options of questionnaires are available. In this study, it was used MMAS-4, one of the most common ways to determine medication adherence [23]. Other instruments may be more detailed and sensitive [24], yet they are not validated and available in Portuguese to assess adherence to T2DM medication. Thus, the rate that was determined by the application of MMAS-4 may be underestimated in relation to the values presented in studies from other countries. On the other hand, the most recent and most comprehensive estimate in Brazil of adherence to oral antidiabetic treatment was below the range described in the literature: only 2% of high adherence [15]. It is noteworthy that adherence in this survey was determined by Brief Medication Questionnaire, an instrument less frequently used for this purpose [23].

In the group with low adherence to treatment, patients were most frequently married; were less likely to engaged regular physical activity; had hypertension as comorbidity; followed therapy based on the combination of two or more oral hypoglycemic agents without insulin; and had a lower perception of the need for medicines. These findings, which may represent barriers to the proper use of T2DM medication, are discussed below.

Lower adherence among married participants was unexpected. Other studies have found the inverse relation [25, 26]. To justify this disagreement, it is arguable that the influence of marital relationship on the evolution and control of T2DM is not simple [27] and may have both positive and negative effects on treatment adherence. In a frayed relationship, where the partner solidarity has been reduced and controlling behaviors accentuated, the married patient may become depressed and thus does not correctly follow the pharmacotherapy. Depression is an important barrier to adherence to T2DM treatment [28], which was not directly evaluated in this study.

The association of non-adherence to medication with low physical activity is poorly reported in the literature. This finding requires further confirmation. Hypothetically it could be a consequence of the patient attitude towards treatment. An important part of T2DM control to exercise regularly [4]. A sedentary patient who intentionally does not comply with this lifestyle change required by the non-pharmacological treatment [29] could also be resistant to correctly use the medication. In this premise, low physical activity would not be a barrier to adherence, but a concomitant behavior. Moreover, as the low adherence group showed little physical activity, in this study no evidence was found that patients not observing the general recommendations for physical activity attempted to compensate by an additional concern to pharmacological treatment or vice versa.

Regarding hypertension, the accumulation of comorbidities implies in increasing the number of medications used, a recognized barrier to adherence [11]. However, in the present study, there was no correlation with low adherence for other coexisting chronic diseases or the number of prescribed drugs. There is evidence that the effect of comorbidities on the adherence rate in T2DM treatment is also complicated. Few comorbidities cause increased adhesion, but many comorbidities result in its reduction, resulting in a U-shaped curve [30].

About the pharmacotherapy, the simultaneous use of metformin and sulfonylurea was more associated with the low adherence group than metformin or sulfonylurea monotherapy. In fact, more complex therapeutic regimens involving more medications are less favorable for adherence [11]. The effect of this barrier can be observed in changes in T2DM pharmacological therapy, where the addition of a new oral hypoglycemic agent throughout treatment has been demonstrated as a risk for reduced medication adherence [31].

Several studies conducted on patients with different diseases show that the N (necessity) and C (concern) scales of the BMQ instrument have respectively positive and negative relationship with medication adherence. Specifically for T2DM, the intensity of the correlation for both scores is intermediate in comparison to other diseases [13, 14]. In the population analyzed in this study, patients with lower N scores were more frequent in the low adherence group. Yet, no association was found with adherence to medication for the C score.

Using the N and C scores, patients were classified as skeptical (2.0%), ambivalent (36.3%), indifferent (4.0%) or accepting (57.7%) according to their perceptions of needs and concerns about medicines. The distribution found, with a predominance of patients with high necessity and low concern (accepting) and high necessity and concern (ambivalent), was similar to published data [20, 21, 32]. Studies in T2DM showed that the accepting group had the highest level of medication adherence while the skeptical group had the lowest adherence [20, 32], but this correlation was not confirmed here.

Since the N score was higher among patients with high adherence, the main determinants for this value were investigated. The variables that significantly increased the N score were the number of prescribed drugs and age. Several research groups reported that adherence increases with age [10], a correlation not observed in this study. However, the results indicate a possible indirect relation of adherence and age considering the increased feeling of need for the drug that accompanies aging. Regarding the number of drugs, the increase in the N score could partially explain why this variable, which is an established factor to non-adherence [11], was not distributed differently between the high and low adherence groups. The contribution of this variable to non-adherence may have found to counterpoint the greater feeling of need for the drugs, i.e., these antagonistic effects may have canceled each other. Still about the N score, the mathematical model found that having diabetes cases in the family and having children decreased the score. These two variables are not usually listed as important factors related to adherence.

In this study, some non-adherence factors were reaffirmed, such as pharmacological therapy based on the combination of metformin and sulfonylurea and having hypertension as comorbidity. The use of oral hypoglycemic agents is a modifiable non-adherence factor. With this information, the physician may choose pharmacotherapeutic alternatives that favor adherence. Other less usual factors were suggested, highlighting aspects of the patient’s family life. Being married was associated with non-adherence. Having relatives who had T2DM or simply having children reduced the feeling of need for the drug, and thus could decrease treatment adherence. These potential factors cannot be modified. In the case of confirmation as adherence barriers, such information may be used to identify individuals at higher risk of low adherence. They would need closer and more frequent follow-up by health professionals, as well as additional incentive to participate in education and information activities about the disease and treatment.

The identification of less usual non-adherence factors could be a consequence of the study design, where the influence of drug availability and costs was diminished. Another explanation could be related to the particularities of the Brazilian population, where adherence factors have been less investigated. In fact, there is important diversity in the conditions for T2DM control in different social and cultural contexts [33]. This diversity justifies that further studies on adherence to T2DM medication should be conducted in different populations, despite the large scientific literature on the subject.

The present study has some limitations. All participants were recruited in the same health center and recruitment was performed non-randomly. Thus, it is not possible to rule out any selection biases. The cross-sectional design makes it impossible to determine the direction of the causality of the factors identified. The exposure of participants to education actions on the importance of medication adherence and the consequences of non-adherence were not evaluated. Finally, adherence assessment was based on self-reports. Although it is the most common method, this strategy is subject to inherent biases. Patients may not remember their medication-taking behaviors correctly. While anonymity is guaranteed, they can also modify responses to hide behavior that they consider inappropriate. At last, there is the possibility of misinterpretation of the questions.

In conclusion, full access to medicines did not assure high adherence to pharmacological treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In this population, the variables associated with a low adherence were: being married; less frequent physical activity; have hypertension; follow therapy based on the combination of two or more oral hypoglycemic agents without insulin; have a low feeling of need for medicines. In the case of the need for medication, this feeling was intensified by the patient’s age and the number of medications used and was attenuated if the patient had family members with the same disease and had children. Distinctive factors to medication non-adherence may be found in populations with full access to medicines. These specific barriers should be considered when planning actions for improving adherence in such populations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

Ethics approval

The study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board from Faculdade de Juazeiro do Norte (CAEE 62656516.4.0000.5624). All participants signed an informed consent form.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, Da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, Malanda B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD (Global Burden of Disease) Study. 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386(9995):743–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetologia. 2018;61(12):2461–98. doi: 10.1007/s00125-018-4729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vrijens B, De Geest S, Hughes DA, Przemyslaw K, Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Dobbels F, Fargher E, Morrison V, Lewek P, Matyjaszczyk M, Mshelia C, Clyne W, Aronson JK, Urquhart J, ABC Project Team A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(5):691–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehane E, McCarthy G. Intentional and unintentional medication non-adherence: a comprehensive framework for clinical research and practice? A discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(8):1468-1477. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Khunti K, Seidu S, Kunutsor S, Davies M. Association Between Adherence to Pharmacotherapy and Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(11):1588–96. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Egede LE, Gebregziabher M, Dismuke CE, Lynch CP, Axon RN, Zhao Y, Mauldin PD. Medication Nonadherence in Diabetes: Longitudinal effects on costs and potential cost savings from improvement. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(12):2533–39. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krass I, Schieback P, Dhippayom T. Adherence to diabetes medication: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2015;32(6):725–37. doi: 10.1111/dme.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaam M, Awaisu A, Ibrahim MI, Kheir N. Synthesizing and Appraising the Quality of the Evidence on Factors Associated with Medication Adherence in Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. Value Health Reg Issues. 2017;13:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire (BMQ): A new method for assessing cognitive representations of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14:1–24. doi: 10.1080/08870449908407311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients’ adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e80633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foot H, La Caze A, Gujral G, Cottrell N. The necessity-concerns framework predicts adherence to medication in multiple illness conditions: A meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(5):706–17. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meiners MMMA, Tavares NUL, Guimaraes AD, Pizzol TSD, Luiza VL, Mengue SS, Merchan-Hamann E. Access and adherence to medication among people with diabetes in Brazil: evidences from PNAUM. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2017;20(3):445–59. doi: 10.1590/1980-5497201700030008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Brasil/Ceará/Crato – Panorama. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/ce/crato/panorama. Accessed 06 Jan 2020.

- 17.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care. 1986;24(1):67–74. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ben AJ, Neumann CR, Mengue SS. The Brief Medication Questionnaire and Morisky-Green Test to evaluate medication adherence. Rev Saude Publica. 2012;46(2):279–89. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102012005000013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salgado T, Marques A, Geraldes L, Benrimoj S, Horne R, Fernandez F. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire into Portuguese. Sao Paulo Med J. 2013;131(2):88–94. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802013000100018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tibaldi G, Clatworthy J, Torchio E, Argentero P, Munizza C, Horne R. The utility of the Necessity—Concerns Framework in explaining treatment non-adherence in four chronic illness groups in Italy. Chronic Illn. 2009;5(2):129–33. doi: 10.1177/1742395309102888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cicolini G, Comparcini D, Flacco ME, Capasso L, Masucci C, Simonetti V. Self-reported medication adherence and beliefs among elderly in multi-treatment: a cross-sectional study. Appl Nurs Res. 2016;30:131–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez JS, Schneider HE. Methodological Issues in the Assessment of Diabetes Treatment Adherence. Curr Diab Rep. 2011;11(6):472–9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-011-0229-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clifford S, Perez-Nieves M, Skalicky AM, Reaney M, Coyne KS. A systematic literature review of methodologies used to assess medication adherence in patients with diabetes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(6):1071–85. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.884491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan X, Patel I, Chang J. Review of the four item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-4) and eight item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) Innov Pharm. 2014;5(3):165. doi: 10.24926/iip.v5i3.347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raum E, Krämer HU, Rüter G, Rothenbacher D, Rosemann T, Szecsenyi J, Brenner H. Medication non-adherence and poor glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;97(3):377–84. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcum ZA, Zheng Y, Perera S, Strotmeyer E, Newman AB, Simonsick EM, Shorr RI, Bauer DC, Donohue JM, Hanlon JT, Health ABC Study. Prevalence and correlates of self-reported medication non-adherence among older adults with coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, and/or hypertension. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(6):817 – 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Trief PM, Ploutz-Snyder R, Britton KD, Weinstock RS. The relationship between marital quality and adherence to the diabetes care regimen. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27(3):148–54. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2398–403. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brundisini F, Vanstone M, Hulan D, Dejean D, Giacomini M. Type 2 diabetes patients’ and providers’ differing perspectives on medication nonadherence: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:516. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briesacher BA, Andrade SE, Fouayzi H, Chan KA. Comparison of drug adherence rates among patients with seven different medical conditions. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;28(4):437–43. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voorham J, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Wolffenbuttel BH, Stolk RP, Denig P. Groningen Initiative to Analyze Type 2 Diabetes Treatment Group. Medication adherence affects treatment modifications in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2011;33(1):121–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mann DM, Ponieman D, Leventhal H, Halm EA. Predictors of adherence to diabetes medications: the role of disease and medication beliefs. J Behav Med. 2009;32(3):278–84. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9202-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caballero AE. The “A to Z” of Managing Type 2 Diabetes in Culturally Diverse Populations. Front Endocrinol. 2018;9(479):1–15. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]