Abstract

Background

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterised by chronic hyperglycemia. The present research work aimed to evaluate the hypoglycaemic, hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of leafy stems of Cissus polyantha Gilg & Brandt in insulin resistant rats.

Methods

The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was performed in normal rats. Hyperglycemia was induced for 8 days by a daily subcutaneous injection of dexamethasone (1 mg/kg) one hour after pretreatment of animals with metformin (40 mg/kg) and C. polyantha extract (111, 222 and 444 mg/kg). Body weight, blood glucose, insulin level, lipid profile, insulin biomarkers, cardiovascular indices and oxidative stress biomarkers were evaluated.

Results

For OGTT, the extract (444 mg/kg) produced a significant drop in blood sugar at the 60th (p < 0.01), 90th (p < 0.01) and 120th min (p < 0.05). Morever, the extract at doses of 222 and 111 mg/kg significantly reduced blood sugar at the 60th (p < 0.01) and 90th min (p < 0.05) respectively. Otherwise, C. polyantha (444 and 222 mg/kg) significantly (p < 0.001) increased body weight and decreased blood sugar on the 4th and 8th days of treatment in insulin resistant rats. The extract also significantly decreased (p < 0.001) serum insulin level, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance index and cardiovascular indices, and increased gluthathione level, and superoxide dismutase and catalase activity.

Conclusion

The aqueous extract of Cissus polyantha leafy stems (AECPLS) possess hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic and antioxidant activities that could justify its use in traditional medicine for the prevention and treatment of diabetes mellitus and its complications.

Keywords: Cissus polyantha, Hypoglycemia, Hypolipidemia, Antioxidant, Insulin resistance

Background

Obesity, oxidative stress, age and many other factors are responsible for tissue resistance to insulin, an early stage of type 2 diabetes mellitus whose major metabolic syndromes are hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and hyperinsulinemia [1, 2]. Hyperglycemia is an important factor responsible for intense oxidative stress in diabetes, and the toxicity induced by glucose autoxidation is likely to be one of the important sources of reactive oxygen species which, causes oxidative damage to the heart, kidneys, eyes, nerves and liver [3]. Nearly a half of billion people currently suffer from diabetes with 4 million deads in 2017 [4]. According to World Health Organization (WHO) in 2017, this carbohydrate metabolic disorder has become a public health problem today.

The therapeutic management of diabetes currently rely on dietary hygiene measures associated with the intake of oral antidiabetic drugs or insulin administration [5]. Unfortunately, these synthesised antidiabetic drugs have revealed numerous adverse side effects such as hypoglycemia, ketoacidosis, gastro-intestinal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, headache, nausea, etc. About 80% of the World’s population resorts to traditional herbal medicine to treat many diseases due to poverty, low adverse effects, precarious health system or easy access to these natural products [6]. For along time diabetics have been treated in folk medicine by the oral intake of various medicinal plants or plant extracts [7]. Ethnobotanical information reveals that around 800 medicinal plants have hypoglycemic or antidiabetic potential [8].. Hence the search for safer and effective antidiabetic agents has become the current research interest area [9]..

Cissus polyantha Gilg & Brandt is a plant member of the Vitaceae family, generally found in tropical regions and used in traditional African medicine for the treatment of inflammation, pain, microbial diseases and diabetes [10, 11]. The antioxidant properties and digestive enzyme inhibitory activity of the aqueous extract from leafy stems of Cissus polyantha has been earlier demonstrated by Mahamad et al. [12] findings. The objective of this study was to evaluate the hypoglycemic, lipid-lowering and antioxidant effects of the AECPLS on a model of dexamethasone- induced hyperglycemia.

Methods

Preparation of plant extract

Cissus polyantha leafy stems were collected in September 2017 in Mémé (Far-North Region, Cameroon). A specimen of this plant was identified at the National Herbarium (Yaoundé-Cameroon), and kept as voucher 44,346/NHC. The leafy stems were dried and ground to obtain a fine powder. One hundred gram (100 g) of this powder were infused in 500 mL of distilled water for 30 min. After filtration and evaporation in an oven, 18.8 g (18.80%) of the crude extract of C. polyantha leafy stems were obtained.

Phytochemical screening

The presence of alkaloids, coumarins, glycosides, flavonoids, phenols, quinones, saponins, steroids, tannins and terpenoids was detected as described by Savithramma et al. [13].

Animals

Animals used in this study consisted of male Wistar rats, aged 10 to 12 weeks and weighing between 220 and 250 g. They were gotten from the animal house of the Department of Biological Sciences of the University of Ngaoundéré (Cameroon). Animals were placed in polystyrene cages (n = 5). Before their use, they were acclimatized for 2 weeks under laboratory conditions (room temperature, relative humidity and a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h). They received free access to water and a standard chow.

The present study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Maroua (Ref. N°14/0261/Uma/D/FS/VD-RC), Cameroon. The animal protocol were accomplished in accordance with the guidelines of Cameroonian bioethics committee (reg N°.FWA-IRB00001954) and NIH- Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Manual (8th Edition).

Choice of plant extract doses

The daily amount of C. polyantha that the traditional healer gives to adult patients is 2.52 g. This mass of extract supposedly consumed by an adult of 70 kg allowed us to calculate the human therapeutic dose which is 36 mg/kg. The equivalent dose in rats was approximately 222 mg/kg, calculated according as per Shannon et al. [14]. The dose of 222 mg/kg obtained was framed by the doses 111 and 444 mg/kg.

Oral glucose tolerance test in normal rat

The rats were fasted for 16 h and divided into groups of 5 rats each. Group I received distilled water (10 mL/kg, p.o). Group II received glibenclamide (0.3 mg/kg, p.o). Group III, IV and V received oral doses of 111, 222 and 444 mg/kg of leafy stems extract of C. polyantha, respectively. Blood was collected from the tail vein of the rats and blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (One touchR ultra 2, Life Scan Europe, 6300zug, Switzerland) at 0, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min of the experiment.

Induction of hyperglycemia and animals treatment

Thirty (30) rats were divided into 6 groups of 5 rats each and treated daily for 8 days according to the protocol previously described [15] with slight modifcations:

Group I (normal control) received distilled water (10 mL/kg b.w.) orally and NaCl (1 mL/kg b.w.) subcutaneously;

Group II (diabetic control) received distilled water (10 mL/kg b.w.) orally and dexamethasone (1 mg/kg) subcutaneously;

Group III (positive control) received the solution of metformin (40 mg/kg b.w.) orally and dexamethasone (1 mg/kg b.w.) subcutaneously;

Groups IV, V and VI received AECPLS (111, 222 and 444 mg/kg respectively) orally and dexamethasone (1 mg/kg b.w.) subcutaneously.

Subcutaneous administrations were achieved 1 h after oral administrations. Rats’ body weight was measured on days 1, 4 and 8 of the experiment.

Collection of blood and organs

On the 8th day (the last day) of the experiment, the animals were fasted for 24 h with free access to water. They were then anesthetised by intraperitoneal injection of the combination of ketamine (50 mg/kg) and diazepam (10 mg/kg) and sacrificed. Blood was collected into dry tubes by cervical decapitation and left to stand for 30 min to coagulation. The coagulated samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4000 rpm to obtain the serum. Serum samples were stored at −20 °C for determination on insulin level and lipid parameters.

After blood collection, the liver, kidneys, and heart of each rat were removed, cleaned in 0.9% NaCl and weighed to determine their relative weight. The organs (heart, liver and kidneys) were then separately crushed, homogenized in 10% (w/v) phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and centrifuged at 4900 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were transferred to labeled microtubes, and stored at −20 °C for oxidative stress markers assay.

Biochemical estimation

Blood glucose level was estimated using One Touch Ultra Mini glucometer (Life Scan Europe, 6300 zug, Switzerland) on days 1, 4 and 8 of the experiment. Fasting blood insulin was measured using rat enzyme immunoassay kits (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, USA). Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated according to the Matthews et al. [16] method using the formula: HOMA-IR = insulin (μg/L) × glycemia (mg/dL)/22.4. Pancreatic beta cell function (HOMA-β) was calculated using the formula: HOMA-β = 20 × insulin (μIU/mL)/FBS (mmol/L) - 3.5) [17]. Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index (QUICKI) was calculated as follows: QUICKI = 1 / (log FBS (mg/dL) + log insulin (μIU/mL)) [18]. Insulin Disposition Index (DI) was evaluated by the following formula: DI = Ln HOMA-β / Ln HOMA-IR [19].

Total cholesterol (TC) was determined according to the enzymatic method [20]. High density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDLc) concentration was evaluated according to the enzymatic colorimetric method described by Weibe et al. [21] using INMESCO kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, USA). Triglycerides (TG) were determined according to the enzymatic colorimetric method described by Cole [22] using DIALAB kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, USA). Low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) concentration was calculated using the equation of Friedwald et al. [23]: LDL-c = TC – (TG/5) - HDLc. Atherogenic index (AI) was calculated using the formula: AI = Log (TG/HDL-c) [24]. Coronary artery risk index (CRI) was calculated according to the methods of Kang et al. [25] using the formula: CRI = TC/HDL-c. Cardioprotective index (CI) was calculated by the following formula: CI = LDLc/ HDL-c [26].

The concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) was determined according to the method described by Quantanilha et al. [27]. The enzymatic activity of catalase (CAT) was determined according to the method described by Sinha [28]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was estimated according to the method described by Misra and Fridovish [29]. Glutathion (GSH) concentration was assayed by the method of Sehirli et al. [30]. All antioxidant parameters were determined using the methods provided by the assay kits (Cayman Chemical Company, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D). The difference between mean values of the various treatments was tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey test and two-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni test, using Graph Pad Prism software version 5.01. Values were considered statistically significant when p ˂0.05.

Results

Qualitative phytochemical analysis

The results of the phytochemical screening of the AECPLS revealed the presence of alkaloids, terpenoids, steroids, tannins, flavonoids, phenols, quinon es and glycosides, and the absence of saponins.

Oral gucose tolerance test

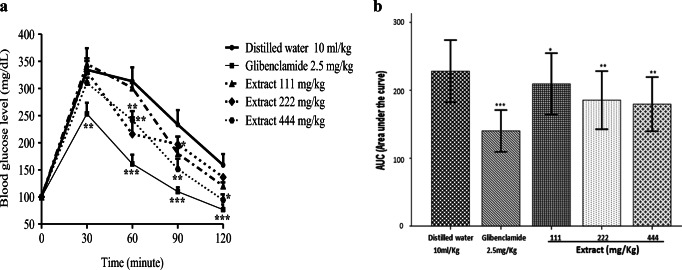

Figure 1 shows the effect of AECPLS on the variation of postprandial glycemia (A) and the area under the curve (B) after glucose overload in normal rats. It appears in Fig. 1A that glibenclamide caused a significant decrease (p < 0.001) in the blood glucose level 2 h after administration, compared to the control group. Similarly, the dose of 444 mg/kg of AECPLS produced a significant drop in blood glucose at the 60th (p < 0.01), 90th (p < 0.01) and 120th min (p < 0.05). In addition, the doses of 222 and 111 mg/kg of AECPLS significantly reduced blood sugar level at the 60th (p < 0.01) and 90th min (p < 0.05) post treatment, respectively. These results are more visible in Figure 1B where the AUC significantly decreased with glibenclamide (p < 0.001) and the doses of 111 (p < 0.05), 222 (p < 0.01) and 444 mg/kg (p < 0.01) of AECPLS, compared to the control group.

Fig. 1.

Effect of the AECPLS during the oral glucose tolerance test (A) and on the area under the curve (B) in normal rats. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared to the control group

Body weight and blood glucose level

Table 1 shows a significant decrease in body weight of diabetic control group rats at the 4th (p < 0.001) and 8th day (p < 0.01) of treatment, compared to the normal control group. However, on the 8th day of treatment, there was a significant increase in the body weight of the rats treated with metformin (p < 0.001) and at doses of 444 (p < 0.05) and 222 mg/kg (p < 0.05) of AECPLS, compared to the rats of the diabetic control group.

Table 1.

Effect of the AECPLS on body weight and blood glucose level in insulin resistant rats

| Groups | Blood glucose level | Body weight (g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1th day | 4th day | 8th day | 1th day | 4th day | 8th day | |

| Normal control | 85.60 ± 10.23 | 85.28 ± 8.41 | 83.86 ± 10.61 | 230 ± 5.21 | 240.11 ± 1.14 | 249.88 ± 3.33 |

| Diabetic control | 83.22 ± 3.12 | 127.25 ± 4.33*** | 149.41 ± 6.42*** | 228 ± 2.12 | 213.96 ± 3.36** | 212.27 ± 8.52*** |

| Dexa + Met (40 mg/kg) | 72.41 ± 6.51 | 91.42 ± 4.85c | 93.80 ± 3.19c | 232 ± 12.25 | 234.19 ± 10.11 | 246.18 ± 9.16c |

| Dexa + Ext (111 mg/kg) | 72.84 ± 2.14 | 104.61 ± 6.15a | 113.43 ± 1.18c | 226 ± 3.42 | 223.20 ± 5.54 | 221.21 ± 2.34 |

| Dexa + Ext (222 mg/kg) | 82.21 ± 2.23 | 105.28 ± 1.17a | 100.22 ± 3.44c | 229 ± 14.12 | 228.90 ± 12.23 | 234.04 ± 5.56a |

| Dexa + Ext (444 mg/kg) | 77.43 ± 14.12 | 102.21 ± 2.22a | 94.25 ± 5.65c | 227 ± 2.25 | 224.31 ± 4.75 | 229.58 ± 0.89a |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). *** p < 0.001 compared to the normal control group. ap < 0.05; bp < 0.01; cp < 0.001 compared to the diabetic control. Dexa: dexamethasone; Met: metformin; Ext: extract.

It appears from this same table that the glycemia of all the experimental animals was almost similar on the first day of treatment. On days 4 and 8, a significant increase (p < 0.001) in blood glucose level was recorded in the diabetic control group, compared to the normal control group. In contrast, there was a significant decrease in blood glucose level in rats treated with metformin (p < 0.001) and at different doses of AECPLS (p < 0.05) on day 4 of treatment, compared to the diabetic control group. This decrease was more significant (p < 0.001) on the last day of treatment.

Insulin level, HOMA-IR, HOMA-β, QUICKI and DI

Table 2 shows a significant increase (p < 0.001) in the level of insulin and HOMA-IR, and a significant reduction (p < 0.001) in the DI of the animals in the diabetic control group, compared to the normal control group.

Table 2.

Effect of AECPLS on insulin level, HOMA-IR, HOMA–β, QUICKI and DI

| Groups | Normal control | Diabetic control | Dexa + Met(40 mg/kg) | Dexa + Extract (mg/kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | 222 | 444 | ||||

| Insulin (μg/L) | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.61 ± 0.02*** | 0.38 ± 0.04c | 0.48 ± 0.02b | 0.40 ± 0.01c | 0.37 ± 0.03c |

| HOMA-IR | 1.14 ± 0.07 | 4.04 ± 0.42*** | 1.60 ± 0.16c | 2.26 ± 0.4c | 1.76 ± 0.15c | 1.52 ± 0.13c |

| HOMA–β | 74.38 ± 0.21 | 71.91 ± 0.66 | 77.40 ± 0.06a | 131.09 ± 0.43c | 128.50 ± 0.16c | 89.66 ± 0.07a |

| QUICKI | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

| DI | 32.88 ± 0.32 | 3.06 ± 0.51*** | 9.25 ± 0.11c | 5.98 ± 0.33c | 8.58 ± 0.09c | 10.73 ± 0.31c |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). *** p < 0.001 compared to the normal control group. ap < 0.05; bp < 0.01; cp < 0.001compared to the diabetic control group. Dexa: dexamethasone; Met: metformin; Ext: extract.

Compared to the diabetic control group, there was a significant decrease (p < 0.001) in insulin level and a significant increase (p < 0.001) in DI in animals treated with metformin and at various doses of AECPLS. Furthermore, HOMA-β values significantly increased with metformin (p < 0.05) and doses of 111 (p < 0.001), 222 (p < 0.001) and 444 mg/kg (p < 0.05) of AECPLS. No significant difference in the QUICKI was noted between the different groups of animals.

Lipid profile and cardiovascular index

Table 3 shows the lipid parameters and the cardiovascular indices of animals treated with AECPLS for 8 days. There was no significant variation of the TC level in different groups of animals compared to the normal control group animals. However, there was a significant increase (p < 0.001) in TG level, LDL-c level, AI and CRI, and a significant decrease (p < 0.001) in HDL-c level and CI in the diabetic control group.

Table 3.

Effect of the AECPLS on the lipid profile and cardiovascular indices of insulin resistant rats

| Groups | Normal control | Diabetic control | Dexa + Met (40 mg/kg) | Dexa + Extract (mg/kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | 222 | 444 | ||||

| TC (mg/dL) | 111.51 ± 4.94 | 116.13 ± 3.39 | 111.64 ± 2.94 | 107.21 ± 3.04 | 106.96 ± 4.70 | 103.54 ± 2.03 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 86.86 ± 1.59 | 118.42 ± 5.76*** | 92.60 ± 3.49b | 99.69 ± 5.33a | 97.44 ± 5.07a | 93.50 ± 4.49a |

| HDL-c (mg/dL) | 57.36 ± 1.27 | 34.26 ± 2.66*** | 5033 ± 2.20b | 45.44 ± 3.49a | 46.75 ± 2.37a | 48.2 ± 1.92b |

| LDL-c (mg/dL) | 35.23 ± 3.70 | 62.11 ± 3.06*** | 42.78 ± 4.35a | 45.00 ± 4.37a | 43.79 ± 4.52a | 36.64 ± 2.49b |

| AI | 0.18 ± 0.15 | 0.53 ± 0.02*** | 0.26 ± 0.08c | 0.34 ± 0.07b | 0.31 ± 0.17b | 0.28 ± 0.12c |

| CRI | 1.89 ± 0.06 | 3.62 ± 0.12*** | 2.23 ± 0.12c | 2.60 ± 0.18c | 2.47 ± 0.17c | 2.15 ± 0.08c |

| CI | 1.75 ± 0.20 | 0.52 ± 0.02*** | 1.24 ± 0.17a | 1.03 ± 0.24a | 1.06 ± 0.17a | 1.35 ± 0.13b |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). *** p < 0.001 compared to the normal control group. ap < 0.05; bp < 0.01; cp < 0.001 compared to the diabetic control group. Dexa: dexamethasone; Met: metformin; Ext: extract.

Metformin induced a significant increase in the concentration of HDL-c (p < 0.01), of the CI (p < 0.05), and a significant decrease in TG level (p < 0.01), LDL-c level (p < 0.05), AI (p < 0.001) and CRI (p < 0.001) compared to the diabetic control group. In addition, animals treated with doses of 111 and 222 mg/kg of extract showed a significant decrease in TG level (p < 0.05), LDL-c level (p < 0.05), AI (p < 0.01) and CRI (p < 0.001), and a significant increase in the level of HDL-c (p < 0.05) and CI (p < 0.05). Similarly, the dose of 444 mg/kg resulted in a significant decrease in TG level (p < 0.05), LDL-c level (p < 0.01), AI (p < 0.001) and CRI (p < 0.001), and a significant (p < 0.01) increase in HDL-c level and CI.

Antioxidant parameters

Table 4 shows that the MDA level significantly increased (p < 0.001) in the liver, heart and kidneys of rats in the diabetic control group, compared to the normal control group. In contrast, compared to the diabetic control group, there was a significant decrease in MDA level in the liver (p < 0.01) and kidneys (p < 0.05) in metformin-treated rats, in the heart (p < 0.05) and liver (p < 0.001) of rats treated at the dose of 222 mg/kg, and in the heart (p < 0.05), liver (p < 0.01) and kidneys (p < 0.001) of rats treated at the dose of 444 mg/kg of AECPLS.

Table 4.

Effect of AECPLS on some antioxidant parameters in insulin resistant rats

| Parameters | Organ | Normal control | Diabetic control | Dexa + Met (40 mg/kg) | Dexa + Extract (mg/kg) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 111 | 222 | 444 | |||||

| MDA (mmol/mg) | Heart | 1.1 ± 0.15 | 3.76 ± 0.28*** | 3.14 ± 0.34*** | 3.56 ± 0.24*** | 2.36 ± 0.31a | 2.22 ± 0.36a |

| Liver | 2.16 ± 0.32 | 8.92 ± 0.58*** | 5.7 ± 0.58**b | 6.42 ± 0.60*** | 5.48 ± 0.61*b | 4.92 ± 0.75*c | |

| Kidneys | 2.6 ± 0.35 | 6.84 ± 0.52*** | 4.6 ± 0.56a | 5.88 ± 0.44*** | 6.36 ± 0.47*** | 4.24 ± 0.48b | |

| CAT (μmol/min/mg) | Heart | 16.9 ± 1.25 | 8.3 ± 1.01* | 16.56 ± 1.50a | 18.32 ± 2.09b | 19.18 ± 1.76b | 20.38 ± 2.30c |

| Liver | 17.86 ± 1.53 | 7.66 ± 0.83** | 18.36 ± 1.22b | 17.26 ± 1.64b | 19.06 ± 2.27b | 22.44 ± 2.23c | |

| Kidneys | 18.68 ± 1.38 | 10.02 ± 0.49* | 17.68 ± 2.54a | 20.26 ± 1.56b | 22.24 ± 2.12c | 21.5 ± 1.62b | |

| SOD (U/mg) | Heart | 10.21 ± 1.82 | 4.82 ± 0.37** | 6.62 ± 0.51 | 5.42 ± 0.50* | 6.82 ± 0.66 | 9.22 ± 1.02a |

| Liver | 13.02 ± 0.89 | 8.43 ± 0.92 | 13.22 ± 1.68a | 10.02 ± 0.70 | 11.02 ± 0.94 | 14.22 ± 0.96b | |

| Kidneys | 0.35 ± 002 | 0.19 ± 0.02* | 0.33 ± 0.02a | 0.37 ± 0.03b | 0.41 ± 0.03c | 0.38 ± 0.03b | |

| GSH (mmol/100 g) | Heart | 26.9 ± 2.63 | 18.64 ± 3.03 | 28.46 ± 2.17 | 25.18 ± 1.77 | 19.82 ± 2.48 | 22.26 ± 3.17 |

| Liver | 40.66 ± 2.91 | 24.96 ± 2.84** | 30.82 ± 2.46 | 34.1 ± 1.76 | 32.24 ± 2.93 | 27.34 ± 2.53 | |

| Kidneys | 35.5 ± 2.31 | 21.66 ± 1.80* | 27.08 ± 3.23 | 31.1 ± 2.98 | 29.16 ± 2.13 | 26.36 ± 4.18 | |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001 compared to the normal control group. ap < 0.05; bp < 0.01; cp < 0.001 compared to the diabetic control group. Dexa: dexamethasone; Met: metformin; Ext: extract.

In result still, there was a significant decrease in the activity of CAT and SOD in the heart (p < 0.05), liver (p < 0.01) and kidneys (p < 0.05) in diabetic control group rats, compared to the normal control group rats. In contrast, rats treated with metformin showed a significant increase in CAT activity in the heart (p < 0.05), liver (p < 0.01) and kidneys (p < 0.05), compared to the diabetic control group. Similarly, rats treated with diiferent doses of AECPLS showed a significant increase (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001) in CAT activity in the heart, liver and kidneys.

A significant decrease in the activity of SOD was observed in the heart (p < 0.05) and kidneys (p < 0.01) in diabetic control group animals, compared to the normal control group. However, with respect to the diabetic control group, animals treated with metformine and the extract at doses of 111, 222 and 444 mg/kg showed a significant increase (p < 0.05 to p < 0.001) in the SOD activity.

Glutathione (GSH) was significantly decreased in the liver (p < 0.01) and kidneys (p < 0.05) of diabetic control group rats, compared to the normal control group rats. GSH levels did not vary significantly in rats treated with metformin and AECPLS.

Discussion

Insulin resistance and oxidative stress are two physiological conditions that promote the onset of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [31]. Overweight, sedentary lifestyle, uncontrolled diet and certain environmental factors are the main causes of these metabolic disorders [32]. The scientific community has developed several treatment and prevention strategies [33]. The nutritional factor incorporating antioxidant and anti-diabetic substances of plant origin remains the most explored in recent years [34, 35]. The chemical composition of plant source polyphenols occupies a dominant position [36, 37]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the antihyperglycemic, antihyperlipidemic and antioxidant potentials of the AECPLS in hyperglycemic rats. Phytochemical studies on the methanolic and aqueous extracts of Cissus polyantha leaves revealed the presence of polyphenols [12, 38].

Chemical compounds like alkaloids, terpenoids, tannins, flavonoids, phenols, quinones and glycosides were identified in the AECPLS. Results obtained during the glucose tolerance test showed that the AECPLS at doses of 111, 222 and 444 mg/kg caused a significant drop in postprandial blood sugar from the 60th min, compared to the group normal control group. This decrease was more prominent with the reference substance (glibenclamide), which significantly reduced hyperglycemia from the 30th min. AECPLS could have acted in the same way as certain oral antidiabetic drugs like glibenclamide, which close K+/ATP channels followed by the membrane depolarization of pancreas cells, key stage for insulin secretion of [39], or by inducing the absorption, storage and use of glucose by different tissues as metformin does [40].

The body weight of rats in the diabetic control group decreased significantly on days 4 and 8 of treatment, compared to animals in the normal control group. It is recognised that dexamethasone induces leptin secretion, a cytokine produced by adipose tissue, involved in satiety signaling processes, lipolysis and proteolysis [41]. This could thus justify the loss of body weight observed in animals in the diabetic control group. On the other hand, a significant increase in the body weight of the animals treated with metformin and at doses of 444 and 222 mg/kg of the extract was noted on the 8th day of treatment. In fact, metformin has a potential effect on the lipogenic and proteogenic activity of insulin preventing weight loss related to the effects of dexamethasone above-elucidated [42]. AECPLS could have therefore acted by the same mechanism.

Animals treated at doses of 111, 222 and 444 mg/kg of AECPLS showed a decrease in blood sugar on the 4th and 8th day of treatment. The lipid profile of the animals treated with the extract showed a significant decrease in the levels of triglycerides, LDL-c and a significant increase in HDL-c level, compared to the diabetic control group. One of the mechanisms of hypoglycemia is increased insulin release and decreased intestinal glucose uptake [43]. According to Tamboli et al. [44], dexamethasone inhibits the insulin signaling pathways, prevents the translocation of GLUT4 in muscle cells and adipocytes, leading to hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia in the diabetic group. These effects are considerably reduced by the reference substance (metformin), which increases the action of insulin in the liver, muscles and adipocytes [42]. AECPLS could have acted by the same mechanisms as metformin. Dexamethasone therefore induced insulin resistance in the diabetic control group animals, which justifies the hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia observed above [45]. Metformin inhibits peripheral dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance [46]. AECPLS contains substances which act either by competitive antagonism on the dexamethasone receptors, or by stimulating the production of repressors and the transcription of the genes of dexamethasone [47, 48].

AI and CI of rats treated with dexamethasone significantly decreased. Furthermore, CRI significantly increased, compared to normal control rats. Metformin and AECPLS significantly changed these parameters, unlike dexamethasone. The risk of cardiovascular disease has been shown to be increased by the hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia observed in insulin resistant animals [49–51]. The improvement in the lipid profile of animals treated with metformin and at different doses of AECPLS suggests a protective effect against atherothrombotic diseases [52, 53].

The action and secretion of insulin are physiologically interconnected [54]. The health of insulin-producing cells and insulin function in type 2 diabetes have revealed insulin-related biomarkers, including QUICKI, HOMA-IR, HOMA-β and DI. Results of the present study indicate that AECPLS has a protective effect in type 2 diabetes by improving beta cell function, increasing insulin sensitivity and reducing insulin resistance index.

After the evaluation of oxidative stress biomarkers in the heart, liver and kidneys, there was a marked increase in MDA level in diabetic control group animals. This rate dropped significantly in animals treated with metformin and AECPLS. MDA is a terminal product of lipid peroxidation, whose increment indicates the installation of oxidative stress [55]. CAT is an enzyme capable of converting hydrogen peroxide into water and molecular oxygen [56]. Its activity increased considerably in animals treated with metformin and the extract compared to the diabetic control group with the effect of a decrease in the activity of reactive oxygen species in the cells. Cardiac, hepatic and renal SOD activity increased in animals treated with metformin and AECPLS, compared to the diabetic control group. This increase was more important in the liver and kidneys. According to Hassan [57], SOD acts by disproportionation of cytotoxic superoxides to easily hydrolyse hydrogen peroxide. AECPLS acts like the reference substance by potentiating the production of SOD, an enzyme involved in the antioxidant defense of the body. Glutathione is a non-enzymatic antioxidant, which acts like catalase by reducing hydrogen peroxide, thereby reducing lipid peroxidation, an oxidative stress factor. The level of glutathione decreased significantly in the liver and kidneys of diabetic animals, compared to other groups of animals where it remained stable indicating a relative balance between ROS and the body’s antioxidant system. Catalase and other antioxidant substances are responsible for the maintenance of this equilibrium [57]. These results are in agreement with those of Irudayaraj et al. [58] who showed that the decrease in oxidative stress in animals treated with metformin and AECPLS is correlated to lower blood sugar levels, moderate lipidemia and a decrease in tissue resistance to insulin. The presence of phenolic compounds such as flavonoids and tannins in the AECPLS could justify the antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic and antioxidant properties observed in the present work. The hydroxyl group of phenolic compounds, renders them of capturing free radicals involved in oxidative stress development [59, 60].

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that AECPLS improves blood glucose levels, lipid profile and protects organs against type 2 diabetes, free radicals and other prooxidant compounds. These effects could be due to the presence of phytoconstituents presents in the plant extract. However, further studies will be necessary to determine and explain the exact mechanisms of action of these bioactive compounds.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried at the Laboratory of Department of Biological Science, Faculty ofSciences, University of Maroua, Cameroon. The authors are grateful to the Head of thislaboratory for providing the facilities, and M. MOUSSA Abame for the purchase of the reagents.

Data of availability

The data analyzed and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

MTA and DA proposed the plant material, harvested and prepared the crude extract. MTA, DM and MO conducted the different tests in laboratory. DM and SKP analyzed the data and drafted the article. AK and SLW corrected the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval

All animal experiments were handled according to the Ethic Committee of the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Maroua (Ref. N°14/0261/ Uma/D/FS/VD-RC), Cameroon. The Animal protocol were accomplished in accordance with the guidelines of Cameroonian bioethics committee (reg N°.FWA-IRB00001954) and NIH- Care and Use of Laboratory Animals manual (8th Edition).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts interest related to this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Reaven GM. The insulin resistance syndrome. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2003;5:364–371. doi: 10.1007/s11883-003-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, Garg R. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation. 2005;111:1448–1454. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nelly Rivera-Yañez, Rodriguez-Canales M, Nieto-Yañez O, Jimenez-Estrada M, Ibarra-Barajas M, Canales-Martinez M, Rodriguez-Monroy MA. Hypoglycaemic and antioxidant effects of propolis of Chihuahua in a model of experimental diabetes. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2018;4360356:10. 10.1155/2018/4360356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.International Diabete Federation. Global overview. Diabetes Atlas. 8th ed. 2017. p. 150.

- 5.Cheng AYY, Funtus IG. Oral antihyperglycaemic therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Can Med Assoc J. 2005;172:213–226. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1031414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matheka DM, Demaio AR. Complementary and alternative medicine use among diabetic patients in Africa: a Kenyan perspective. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;15:110. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2013.15.110.2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhtar FM, Ali MR. Study of the antidiabetic effect of a compound medicinal plant prescription in normal and diabetic rabbit. J Pakistan Med Assoc. 1984;34:239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanjhiyana S, Garabadu D, Ahirwar D, et al. Hypoglycemic activity studies on root extracts of Murraya koenigii root in Alloxan-induced diabetic rats. J Nat Prod Plant Resour. 2011;1:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patil AA, Koli AS, Darshana A, Patil B, Narayane CV, Phatak VAA. Evaluation of effect of aqueous slurry of Curculigo orchioides aertn rhizome in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Pharm Res. 2013;7:747–745. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burkill H. The useful plants of west tropical africa. Royal Botanic Garden Kew. 2000;5:290. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sani Y, Musa A, Pateh U, et al. Phytochemical screening and preliminary evaluation of analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of the methanol root extract of Cissus polyantha. BAJOPAS. 2014;7:19–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahamad AT, Miaffo D, Poualeu Kamani S, Kamanyi A, Wansi SL. Antioxidant properties and digestive enzyme inhibitory activity of the aqueous extract from leafy stems of Cissus polyantha. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2019;2019:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2019/7384532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savithramma N, Rao ML, Rukmini K, Devi PS. Antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized by using medicinal plants. Int J of Chem Tech Res. 2011;3:1394–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shannon R, Nihal M, Ahmad N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. Federation Am Societies Experimental Biol J. 2008;22:659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fofié KC, Nguelefack-Mbuyo EP, Tsabang N, Kamanyi A, Nguelefack BT. Hypoglycemic properties of the aqueous extract from the stem bark of Ceiba pentandra in dexamethasone-induced insulin resistant rats. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2018;2018:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2018/4234981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Y, Wang Y, Huang Q, Ren Q, Chen S, Zhang A, et al. Impaired β cell function in Chinese newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus with hyperlipidemia. J Diabetes Res. 2014;493039:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2014/493039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Lin W, Lin N, Dong X, Liu L. Study of the correlation between serum ferritin levels and the aggregation of metabolic disorders in non-diabetic elderly patients. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:1671–1676. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trinder P. Quantitative in vitro determination of cholesterol in serum and plasma. Ann Clin Biochem. 1969;6:24–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiber DA, Warnick GR. Measurement of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Handbook of lipoprotein testing. Washington: AACC Press; 1997. pp. 44–127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cole TG, Klotzsch SG, Mcnamara J. Measurement of triglyceride concentration. In: Rifai N, Warnick GR, Dominiczak MH, editors. Handbook of lipoprotein testing. Washington: AACC Press; 1997. pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentrationof low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma without use of the preparativeultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rafieian-Kopaei M, Shahinfard N, Rouhi Boroujeni H, Gharipour M, Darvishzadeh-Boroujeni P. Effects of Ferulago angulata extract on serum lipids and lipid peroxidation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014; 680856:4. 10.1155/2014/680856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Kang HT, Kim JK, Kim JY, Linton JA, Yoon JH, Koh SB. Independent association of TG/ HDL-c with urinary albumin excretion in normotensive subjects in a rural Korean population. Clin Chim Acta. 2012;413:319–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barter P, Gotto AM, La Rosa JC. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1301–1310. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quantanilha AT, Packer L, Szyszlo DJA, Racnelly TL, Davies KJA. Membrane effects of vitamin E deficiency bioenergetic and surface charge density of skeletal muscle and liver mitochondria. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;393:32–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb31230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinha AK. Colorimetric assay of catalase. Anal Biochem. 1972;47:389–394. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(72)90132-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Misra HP, Fridovish I. The role of superoxide anion in the autoxidation of epinephrine and a sample assay for superoxide dismustase. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:3170–3175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sehirli O, Tozan A, Omurtag GZ, Cetine S, Contuk G, Gedik N, et al. Protective effects of resveratol against naphtylene-induced oxidative stress in mica. Ecoto Environ Safe. 2008;71:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stump CS, Clark SE, Sowers JR. Oxidative stress in insulin-resistant conditions: cardiovascular implications. Treat Endocrinol. 2005;4:343–351. doi: 10.2165/00024677-200504060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reaven GM. Banting lecture. Role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595–1607. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clark CM, Jr, Lee DA. Prevention and treatment of the complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1210–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen A, Horton ES. Progress in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: new pharmacologic approaches to improve glycemic control. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:905–917. doi: 10.1185/030079907x182068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeh GY, Eisenberg DM, Kaptchuk TJ, Phillips RS. Systematic review of herbs and dietary supplements for glycemic control in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1277–1294. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.4.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray AM, Flatt PR. Pancreatic and extra-pancreatic effects of the traditional anti-diabetic plant, Medicago sativa (lucerne) Br J Nutr. 1997;78:325–334. doi: 10.1079/bjn19970150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frei B, Higdon JV. Antioxidant activity of tea polyphenols in vivo: evidence from animal studies. J Nutr. 2003;133:3275–3284. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3275S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sani Y, Musa A, Yaro A, Sani M, Amoley A, Magaji MG. Phytochemical screening and evaluation of analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of the methanol leaf extract of Cissus polyantha. J Med Sci. 2013;10:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pari L, Latha M. Antidiabetic effect of Scoparia dulcis: effect on lipid peroxidation in streptozotocin diabetes. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2005;24:13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valsa AK, Sudheesh S, Vijayalakshmi NR. Effect of catechin on carbohydrate metabolism. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1997;34:406–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahendran P, Shyamala Devi CS. Effect of Garcinia cambogia extract on lipids and lipoprotein composition in dexamethasone administered rats. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;45:345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossetti L, DeFronzo RA, Gherzi R, et al. Effects of metformin treatment on insulin action in diabetic rats: in vivo and in vitro correlations. Metabolism. 1990;39:425–435. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90259-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ovalle-Magallanes B, Medina-Campos ON, Pedraza-Chaverri J, Mata R. Hypoglycemic and anti hyperglycemic effects of phytopreparations and limonoids from Swieteniahumilis. Phytochemistry. 2015;110:111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashpak Tamboli M, Sujit Karpe T, Sohrab Shaikh A, Anil Manikrao M, Dattatraya KV. Hypoglycemic activity of extracts of Oroxylum indicum (L.) vent roots in animal models. Pharmacologyonline. 2011;2:890–899. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weinstein SP, Wilson CM, Pritsker A, Cushman SW. Dexamethasone inhibitsinsulin-stimulated recruitment of GLUT4 to the cell surface in rat skeletal muscle. Metabolism. 1998;47:3–6. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey CJ. Metformin: a useful adjunct to insulin therapy? Diabet Med. 2000;17:83–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00216-7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jyoti M, Vihas TV, Ravikumar A, Sarita G. Glucose lowering effect of aqueous extract of Enicostemma littorale Blume in diabetes: a possible mechanism of action. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002;81:317–320. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schacke H, Rehwinkel A. Dissociated glucocorticoid receptor ligands. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:524–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferrannini E, Haffner SM, Mitchell BD, Stern MP. Hyperinsulinaemia: the key feature of a cardiovascular and metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia. 1991;34:416–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00403180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Daly ME, Vale C, Walker M, Alberti KG, Mathers JC. Dietary carbohydrates and insulin sensitivity: a review of the evidence and clinical implications. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1072–1085. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.5.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Defronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance: a mullifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabete Care. 1991;14:173–194. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Geohas J, Daly A, Juturu V, Finch M, Komorowski JR. Chromium picolinate and biotin combination reduces atherogenic index of plasma in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a placebo-controlled, double-blinded, randomized clinical trial. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333:145–153. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318031b3c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper ME. Pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment of diabetic neuropathy. Lancet. 1998;352:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance versus insulin deficiency in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: problems and prospects. Endocr Rev. 1998;19:477–490. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.4.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Limaye PV, Raghuram N, Sivakami S. Oxidative stress and gene expression of antioxidant enzymes in the renal cortex of streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;243:147–152. doi: 10.1023/a:1021620414979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mates JM, Perez-gomez C, Nunez De Castro I. Antioxidant enzymes and human diseases. Clin Biochem. 1999;32:595–603. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(99)00075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hassan HM. Biosynthesis and regulation of superoxide dismustases. Free Radic Biol Med. 1988;5:377–385. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(88)90111-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karihtala P, Soini Y. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant mechanisms in human tissues and their relation to malignancies. Apmis. 2007;115:81–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2007.apm_514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Irudayaraj SS, Sunil C, Duraipandiyan V, Ignacimuthu S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of Toddalia asiatica (L.) lam. Leaves in streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;143:515–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Urquiaga I, Leighton F. Plant polyphenol antioxidants and oxidative stress. Biol Res. 2000;33:55–64. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602000000200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rajat B. Screening and quantification of phytochemicals and evaluation of antioxidant activity of Albizia chinensis (Vang): one of the tree foliages commonly utilized for feeding to cattle and buffaloes in Mizoram. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2015;4:305–313. [Google Scholar]