Abstract

Purpose

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is one of the most important neurodegenerative diseases and accompanied by the production of free radicals and inflammatory factors. Studies have shown that p-cymene has anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects. Here, the effects of this compound were investigated on a rat model of AD.

Methods

In order to create Alzheimer’s rat model, bilateral injection of Amyloid β1–42 (Aβ1–42) into rats hippocampus was performed. Both therapeutic (post-AD induction) and preventive effects of p-cymene consumption with doses of 50 and 100 mg/kg were investigated. In addition, the effects of adding short-term exercise to the process were also observed. In vitro, Aβ1–42 peptide was driven toward fibril formation and effect of p-cymene was observed on the resulting fibrils.

Results

Learning and memory indices in the AD rats were significantly reduced compared to the Sham group, while p-cymene consumption with both doses, as well as performing exercise counteracted AD consequences. Moreover, increased neurogenesis and reduced amyloid plaques counts were observed in treated rats. In vitro formed fibrils of Aβ1–42 were partially disaggregated in the presence of p-cymene.

Discussion

p-Cymene could act on this AD model via antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties as well as direct anti-fibril effect.

Conclusion

p-cymene can improve AD-related disorders including memory impairment.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40200-020-00658-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cymene, Fibril, Aβ1–42, Alzheimer’s disease, Rat

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurological disorder associated with neuronal degeneration and characterized by loss of learning memory and cognitive impairment [1]. The main symptoms of this disease include neurodegeneration and synaptic loss with the presence of cellular amyloid beta (Aβ) deposition and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles in the various regions of the cerebral cortex. Presently, various lines of evidence suggest that Aβ plays a central role in the pathogenesis of neural abnormal functions. Aβ is a potent neurotoxic peptide and a major structure in the aging plaques. This peptide is a product of beta-amyloid precursor protein (APP) breakdown. In the brain, there are two main forms of Aβ with 40 and 42 amino acids forming Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42, respectively [2]. According to global reports, 46.8 million people were affected with dementia worldwide in 2015. These numbers are expected to increase about 2 times every 20 years [3].

Monoterpenes are the main chemical compounds of essential oils of various herbs and form a mixture of odorous components that can be extracted from a large variety of aromatic plants including edible and medicinal plants with therapeutic properties [4–6].

P-cymene is an aromatic monoterpene widely used for the synthesis of P-cresol [7]. It is a natural compound found in oils of more than 100 plants, including angiospermic plants [8, 9]. It is also used as an important mediator in drugs and as a flavoring agent [10] and is widely present in more than 200 types of foods, including orange juice, grape fruit, mandarin, carrots, raspberries, butter, nutmeg, oregano, and almost every spice [11]. P-cymene has an anti-inflammatory [12], analgesic [13], and anti-tumor [14] effects. More importantly, it also provides anti-oxidant effects [12, 15, 16]. As many evidence suggests that inflammatory pathways and oxidative stress play key roles in the pathogenesis of AD [17], in the present study, the latter effects of p-cymene have been investigated on Alzheimer’s rat models.

On the other hand, physical activity has been proposed as a non-pharmacological (yet effective way) of reducing cognitive decline [18], and recent studies suggest that exercise can affect the hippocampus in a positive way [19].

In the present study, both therapeutic and preventive effects of different doses of p-cymene, as a natural compound, were investigated on Aβ42 fibrillation using Alzheimer’s rat brain as an in vivo model system. The effect of short-term exercise (as added to p-cymene consumption or as an independent treatment) was also investigated on various Alzheimer’s disease indices. Moreover, as an in vitro experiment, Aβ42-preformed fibrils were observed in the presence of p-cymene to further determine the possible destabilizing mechanism of this compound.

Materials and methods

Compounds

Aβ42 and p-cymene were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The 1 mg vial of beta-amyloid, Aβ1–42 was dissolved by 200 μL of double-distilled water, and placed in an incubator at 37 °C for 1 week before use [20, 21] . P-cymene doses (50 and 100 mg/Kg) were also prepared in double-distilled water.

Animals

72 male Wistar rats weighing 200 ± 50 g were purchased from Pasteur Institute of Iran. Rats were kept in in standard cages at 20 °C and light and darkness cycle was maintained at 12:12 h. Animals had free access to water and food. To induce Alzheimer’s disease (AD), animals were anesthetized by ketamine and xylasin injection and placed within stereotactic device. Using stereotaxy and brain atlas [22] to localize hippocampus, 2 μL of beta-amyloid solution was injected slowly with a hamilton syringe in the the CA region on both sides of the hippocampus. After one week, amyloid plaques were formed in the animal’s brain, which were visible by the use of histological methods. Experimental procedures were carried out strictly in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of laboratory Animal Resources, 1996), and approval was received from the Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch Animal Ethics Committee (No 63688/29/8). All experiments including administration of p-cymene, exercise, or combination of exercise and administration of p-cymene were done for a total of three weeks. In the protective mode, p-cymene was administered one week prior to Abeta injection.

Experimental groups (n = 6 in each group) were defined as follows:

Control group (Ctrl): Received regular water and food and did not undergo surgery.

Second control group (S + W): Underwent surgery, and distilled water was injected into their brain’s ventricles.

Exercise Group (Ex): Exercised on treadmill and did not go under any surgery.

Alzheimer’s group (Aβ): Underwent surgery, and beta-amyloid solution was injected into their brain’s ventricles.

Sham group (Aβ + W): Prepared similar to group #4 and then received distilled water (as the compound solvent) through intraperitoneal injection.

Alzheimer’s and exercise (Aβ + Ex): Prepared similar to group #4 and exercised on treadmill.

Experimental group 1 & 2 (Aβ + T + 50 and 100): Prepared similar to group #4 and received therapeutic doses of 50 and 100 mg/kg of p-cymene respectively.

Experimental group 3 & 4 (Aβ + P + 50,100): Received protective dose of 50 and 100 mg/kg of p-cymene respectively and underwent Aβ injection (induction of AD).

Experimental group 5 & 6 (Aβ + EX+50,100): Prepared similar to group #4, exercised on treadmill, and received therapeutic dose of 50 and 100 mg/kg of p-cymene respectively.

At the end of the experiment period, animals were anesthetized and blood samples were taken from the heart. Serum was separated using a centrifuge and stored in a freezer at −20 °C. Brain was removed, rinsed with physiological serum, and placed in glass containers containing 10% formalin and later processed for paraffin embedding.

Passive avoidance learning

A box consisting of 2 chambers of equal size (26 × 26 cm) separated by a sliding door (8 × 8 cm) was used for the test. Each experiment began with a pre-test: the rat was first placed in the chamber for 5 s. After that, the sliding door was raised and the rat was allowed to remain in the dark chamber for 10 s, after what it was returned to its cage and left inside for 30 min. The rat was then put back into the shuttle box and received a shock after entering the dark area (50 HZ, 1 mA for 5 s). This part constitutes the acquisition phase, where the rat learns that moving to the dark chamber has unpleasant consequences (rats are naturally keen to go toward the dark section). After this, the rat was brought back into its cage and stayed there for 120 s, and then again put back into the shuttle box. If a 300 s delay was observed before entering the dark area, passive avoidance pass was registered. A similar process was used 24 h after the training periods in order to assess long-term memory. The basis of that experiment is the fact that latency could be considered as indicative of increase or decrease in memory retention [23, 24].

Histological assessment

Hematoxyllin eosin staining was done to assess neurogenesis. Thioflavin S staining method was employed to detect amyloid plaques, and the images were observed by a fluorescence microscope [25].

Measurement of biochemical parameters

Serum levels of malone dialdehyde (MDA) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity level were measured using ELISA kit from the ZellBio GmbH (Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SOD measurement is made based on the enzyme ability to inhibit the autooxidation of pyrogallol, which is checked at 420 nm [26], while MDA reacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) in serum to produce a state of MDA-TBA, which is then measured by colorimetric (OD = 532) method [27].

Exercise test

In order to perform exercise with treadmill, the rats were first acquainted with the treadmill before testing. Since short-term exercise was studied here, the group was trained for 5 consecutive days (incrementing the exercise time) in order to finally reach 1 h daily exercise, at a speed of 17 m/min [28]. Exercising was done for 21 days.

In vitro experiment

Aβ42 peptide was first dissolved in deionized water (DW) to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. In order to make mature fibrils, tubes containing monomers were incubated at 37 °C for 2 and 4 days while the water bath containing the tubes was being gently stirred by a Teflon magnetic bar.

In order to check the destabilization potential of p-cymene, stock solutions of all compounds were prepared in DW as solvent. In the fibrillary Aβ solutions, the final concentrations of p-cymene was set at 50 and 100 μM. For destabilization experiments, aliquots of 1 mg/ml of four-day-old preformed Aβ fibrils were further incubated with the compounds at 37 °C for 3 weeks [29]. In all experiments, the water bath containing the tubes of samples was being gently stirred by a Teflon magnetic bar.

Transmission Electron microscopy

About 5 μL of 1 mg/ml samples were adsorbed onto copper 400 meshF-C grids and let for 2 min. Excess fluid was then removed and 5 μL of 1% uranyl acetate was added onto the grid. Excess dye was removed after 2 min and samples were observed after being completely dried out with the use of Hitachi HU-12A electron microscope (Hitachi, Japan).

Statistical analysis

SPSS software 21 was used with ANOVA and TUKEY analysis of variance in order to investigate the significant differences between the groups. Data is reported as MEAN ± SEM with significance level of P < 0.05 for groups at all stages.

Results

Since multiple groups were investigated in this study, the overall results which include statistical comparison of the groups are reported as Tables or graphs, while the original histological results images are placed in a supplementary file.

Effects of p-cymene consumption after disease induction on biochemical factors, passive avoidance learning, and brain tissue histology

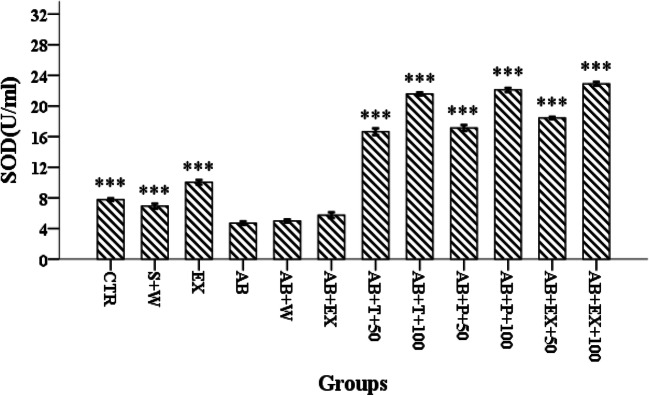

While serum levels of SOD were lowered in the disease-induced groups compared with control and sham groups, SOD levels of the groups treated with p-cymene, i.e., Aβ + T + (50 or 100 mg/kg), were significantly increased compared to the Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups (Fig. 1 and Table S1 in supplementary file for all details). On the other hand, serum levels of MDA in the p-cymene treated groups at both doses were significantly lower than Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups. The dose-dependency of the effect is more remarkable in this case, with the higher dose of p-cymene being more effective (Fig. 2 and Table S2 in supplementary file with more details). (P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Overall serum levels of SOD in different groups. ***: p < 0.001, with the Alzheimer’s disease group put as reference group. Please refer to the Methods section for groups’ definition

Fig. 2.

Overall serum levels of MDA in different groups. ***: p < 0.001, with the Alzheimer’s disease group put as reference group. Please refer to the Methods section for groups’ definition

Statistical analysis of the behavioral test showed that there was a significant difference between the group treated with lower dose of the compound and Ctr, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, Aβ + Ex, and S + W groups, while the group treated with higher dose showed differences with Aβ,Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups. In this instance, p-cymene consumption seems to restore the measured parameters toward normal levels (Table 1, and Fig.S1 of supplementary file). (P < 0.01) (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Shuttle box results difference significance between groups

| Ctrl | S + W | Ex | AB | AB+W | AB+Ex | AB+T + 50 | AB+T + 100 | AB+P + 50 | AB+P + 100 | AB+EX+50 | AB+EX+100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | *** | – | ** | – |

| S + W | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | * | – | * | – | – | – |

| Ex | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | *** | – | ** | – |

| AB | *** | *** | *** | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+W | *** | *** | *** | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+Ex | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+T + 50 | *** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | – | * |

| AB+T + 100 | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AB+P + 50 | *** | * | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | – | * |

| AB+P + 100 | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AB+EX+50 | ** | – | ** | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| AB+EX+100 | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | * | – | * | – | – | – |

Ctr: control, S + W: surgery and injection water, Ex:exercise, AB:receiving amyloid beta, AB+W: receiving amyloid beta and water, AB+Ex: receiving amyloid beta and exercise, AB+T + 50: receiving amyloid beta and therapeutic dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+T + 100: receiving amyloid beta and therapeutic dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+P + 50: receiving amyloid beta and protective dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+P + 100: receiving amyloid beta and protective dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+EX+50: receiving amyloid beta and exercise and dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+EX+100: receiving amyloid beta and exercise and dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymene

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

Amyloid plaques formation and reduced neurogenesis occur both as a consequence of inducing Alzheimer’s disease. Treatment with p-cymene results in a higher number of neurons and decreased amount of plaques in both treated groups, which were significantly different from that of Ctr,S + W,Ex,Aβ,Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups (Tables 2 and 3 show the final results while original images of histological experiments and a graph representation of the results could be found in Fig. S2-S5 of supplementary file). (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Plaque numbers difference significance between groups

| Ctrl | S + W | Ex | AB | AB+W | AB+Ex | AB+T + 50 | AB+T + 100 | AB+P + 50 | AB+P + 100 | AB+EX+50 | AB+EX+100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| S + W | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| Ex | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB | *** | *** | *** | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+W | *** | *** | *** | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+Ex | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+T + 50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | *** | – | * | *** | *** |

| AB+T + 100 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | ** | – | – | *** |

| AB+P + 50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | ** | – | – | ** | *** |

| AB+P + 100 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | – | – | – | – | *** |

| AB+EX+50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | ** | – | – | *** |

| AB+EX+100 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – |

Ctr: control, S + W: surgery and injection water, Ex:exercise, AB:receiving amyloid beta, AB+W: receiving amyloid beta and water, AB+Ex: receiving amyloid beta and exercise, AB+T + 50: receiving amyloid beta and therapeutic dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+T + 100: receiving amyloid beta and therapeutic dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+P + 50: receiving amyloid beta and protective dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+P + 100: receiving amyloid beta and protective dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+EX+50: receiving amyloid beta and exercise and dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymene, AB+EX+100: receiving amyloid beta and exercise and dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymene. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

Table 3.

Neuron numbers difference significance between groups

| Ctrl | S + W | Ex | AB | AB+W | AB+Ex | AB+T + 50 | AB+T + 100 | AB+P + 50 | AB+P + 100 | AB+EX+50 | AB+EX+100 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ctrl | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| S + W | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – |

| Ex | – | *** | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+W | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+Ex | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | *** | *** | ** | *** | *** | *** |

| AB+T + 50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | *** | *** |

| AB+T + 100 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | – | – | – | – | *** |

| AB+P + 50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | ** | – | – | – | * | *** | *** |

| AB+P + 100 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | – | * | – | – | *** |

| AB+EX+50 | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | – | *** | – | – | ** |

| AB+EX+100 | *** | – | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ** | – |

Ctr: control, S + W: surgery and injection water, Ex:exercise, AB:receiving amyloid beta, AB+W: receiving amyloid beta and water, AB+Ex: receiving amyloid beta and exercise, AB+T + 50: receiving amyloid beta and therapeutic dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymen, AB+T + 100: receiving amyloid beta and therapeutic dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymen, AB+P + 50: receiving amyloid beta and protective dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymen, AB+P + 100: receiving amyloid beta and protective dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymen, AB+EX+50: receiving amyloid beta and exercise and dose 50 (mg/kg) of p-cymen, AB+EX+100: receiving amyloid beta and exercise and dose 100 (mg/kg) of p-cymen. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001

Protective effects of p-cymene on biochemical factors, passive avoidance learning and brain tissue histology

Serum levels of SOD in the groups which had received 50 or 100 mg/kg p-cymene in the protective mode were significantly higher than Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups (Fig. 1 and Table S1 in supplementary file for all details). On the other hand, serum levels of MDA in Aβ + P (50 or 100 mg/kg) p-cymene were significantly lower than Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W and Aβ + Ex groups (Fig. 2 and Table S2 in supplementary file with more details). (P < 0.001).

Statistical analysis of the behavioral test showed that there were significant differences between groups Aβ + P + 50 mg/kg p-cymene and Ctr, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, Aβ + Ex and S + W groups, while for Aβ + P + 100 mg/kg p-cymene, significant difference was observed with Aβ, Aβ + W and Aβ + Ex groups (Table 1, and Fig.S1 of supplementary file). (P < 0.01) (P < 0.001).

In histological images, the number of neurons and plaques showed a significant difference between Aβ + P + 50 or 100 mg/kg p-cymene with Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups (Tables 2 and 3 show the final results while original images of histological experiments and a graph representation of the results could be found in Fig. S2-S5 of supplementary file). (P < 0.01) (P < 0.001).

Exercise effects on Alzheimer’s disease model

It should be noted that the exercise period was short in this experience, nevertheless, some differences were found in measured parameters for the groups which underwent exercise (alone) or as a complement to therapy.

Serum levels of SOD in the EX group were significantly different with control, disease-induced and groups treated with p-cymene with or without exercise, while for MDA levels, with the exception of the control group, there was still a significant difference with the other groups (Figs. 1, 2 and Table S1 and S2 in supplementary file for all details). The overall result was that a slight improvement could be observed for animals that had done exercise, compared with the other normal animals. (P < 0.001).

In behavioral tests, EX group results were significantly different with Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups, which showed that the EX group was somehow equivalent with the control group (Table 1, and Fig.S1 of supplementary file). (P < 0.001).

Histological images show that the count of neurons in the EX group was significantly different from that of the S + W, Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups and the count of plaques in the EX group was significantly different from that of the Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups, again showing similarity with normal animals (Tables 2 and 3 show the final results while original images of histological experiments and a graph representation of the results could be found in Fig. S2-S5 of supplementary file). (P < 0.001).

Combined effects of exercise and treatment with p-cymene were also assessed and showed that serum levels of SOD were significantly different in the groups Aβ + EX +50 or 100 mg/kg p-cymene with Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, and Aβ + W groups. Serum levels of MDA in the groups Aβ + EX +50 or 100 mg/kg p-cymene had also significant difference with Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, and Aβ + W groups (Figs. 1, 2 and Table S1 and S2 in supplementary file for all details). (P < 0.001).

In behavioral tests, Aβ + EX +50 mg/kg p-cymene were significantly different with Aβ, Aβ + W Aβ + Ex as well as Ctr and Ex groups, while Aβ + EX +100 mg/kg p-cymene showed differences with Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups (Table 1, and Fig.S1 of supplementary file). (P < 0.01) (P < 0.001).

Histological images showed a significant difference between the number of neurons and plaques in group Aβ + EX +50 mg/kg p-cymene compared to Ctr, S + W, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W and Aβ + Ex groups while for the higher dose of p-cymene combined with exercise, a significant difference was found with Ctr, Ex, Aβ, Aβ + W, and Aβ + Ex groups (Tables 2 and 3 show the final results while original images of histological experiments and a graph representation of the results could be found in Fig. S2-S5 of supplementary file). (P < 0.001).

Destabilizing effects of p-cymene on preformed Aβ42 fibrils in vitro

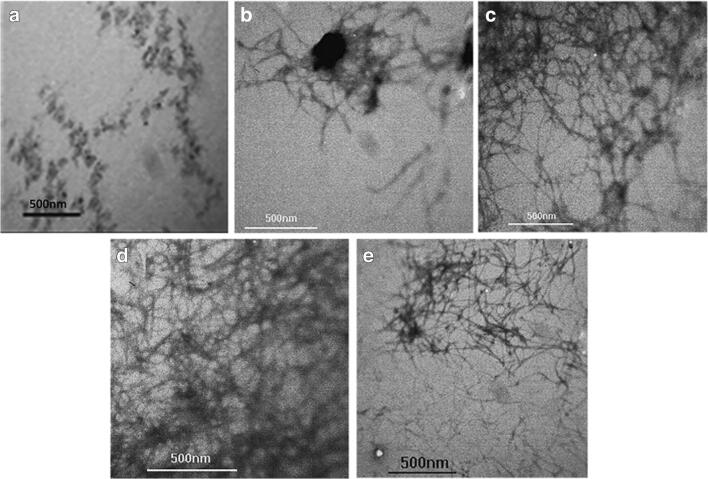

The second part of this study involved monitoring destabilizing effect of p-cymene 100 μM on four-day-old preformed Aβ42 fibrils for 3 weeks of incubation in vitro. It was first demonstrated that Aβ42 fibrillation proceeded from monomeric species to short fibrillar species after 2 days, and then eventually to longer and well-matured fibrils after 4 days (Fig. 3a-c).

Fig. 3.

Electron microscope analysis of Aβ42 fibrillation with and without p-cymene. TEM images of Aβ42 fibrillation process after immediate incubation (a), 2 days (b), and 4 days (c) in the absence of p-cymene. The second row indicates the four-day-old Aβ42 fibrils incubated with p-cymene 100 μM for 1 week (d) and 3 weeks (e)

During the first week of incubation, TEM images revealed no considerable fibrils removal by p-cymene (Fig. 3d). However, images taken from samples incubated for three weeks showed the presence of much shorter fibrillar structures, as compared to Aβ42 fibrils (Fig. 3e).

It was confirmed that inhibition of fibril formation occurred after more than one week incubation in the presence p-cymene 100 μM which was in accordance with the removal of fibrillary plaques over in vivo treatment.

Discussion

Administration of p-cymene was effective in counteracting the deleterious effects of AD on the memory of an animal model. These effects were also apparent at a histological level, while AD-generated brain plaques diminished and a relative increase in neurogenesis was observed. An overall dose-dependency was observed for p-cymene effect, and both therapeutic and protective modes of p-cymene consumption were effective.

As shown in previous studies, injection of an aqueous solvent alone has no particular effect on animals with regard to AD-related consequences (i.e. plaque formation in brain, and impairment of memory) [30].

On the other hand, for the AD group which had exercised, slight differences were observed with the AD groups, but the combination of exercise and p-cymene had no remarkable difference when compared with the p-cymene group alone.

The in vitro experiment has also shown that p-cymene has indeed a potential to influence pre-formed fibrils.

Aβ1–42 plays a key role in the pathogenesis of AD disease [31, 32]. Injection of abeta fibrils onto animals brain is now an established method of generating AD model. These animals show impaired memory and amyloid plaques are formed in their brain. These signs could be counteracted by potential anti-amyloid compounds, which have been mainly suggested to possess aromatic or other polycyclic components as anti-fibrillation component [33, 34], but monoterpenes have also emerged as a class of compounds that could prevent neurotoxicity [35]. Monoterpenes are important chemical compounds that are present in essential oils from plants and possess various therapeutic properties, including antioxidant and anti-inflammatory ones [36, 37], which makes them interesting compounds for treatment of AD, where oxidative stress is also part of the pathology [17].

Over the past decade, it has been suggested that inflammation plays a key role in the pathogenesis of AD [38] and MAPK is considered to be important in this regard [39]. Inflammation could occur in AD brain and be related a high level of inflammatory cytokines [40, 41]. NF-KB activity has also been reported in AD pathogenesis and could be considered as a target to treat the disease [42, 43]. Actually, inhibition of NF-KB activity decreases the Aβ levels in mouse model of AD [44] and since early stages of AD are associated with the presence of P38MAPK, AD patients may benefit from P38MAPK inhibitors [45]. Studies have reported that P-cymene can reduce inflammatory responses via inhibition of IL-1B, IL-6, and TNF-α production inhibition [46], as well as inhibition of MAPK and NF-KB activities [47].

Further than antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, we believe that the results of this experiment show that p-cymene could also act on this AD model via its anti-fibril effect that has been demonstrated in the in vitro experiment. Anti-fibrillation effect of aromatic compounds, especially larger polycyclic chemicals has been reported for a variety of compounds and on various types of fibrils [29, 48].

Finally, it was interesting to observe that even exercise alone could provide beneficial effects with regard to plaque numbers (decrease) or memory (improvement). Previous studies have reported that exercise can protect neurons from various brain damage as well as improve cognitive function in healthy and AD animal models [49–51]. More specifically, amyloid plaques have been reported to be diminished upon exercising with treadmill (as used in the current study) [52]. The effect is stated to be “dose-dependent”, and it may be suggested that using higher intensity of exercise could be more beneficial, especially when coupled with another therapeutic mean.

In conclusion, p-cymene has been demonstrated to counteract deleterious effects of AD in a rodent model, when used either protectively or as a therapeutic mean. While short-term exercise was also effective on attenuating AD-related symptoms, no synergetic effect was observed in the combination of p-cymene and exercise. Further studies could show whether higher intensity or longer periods of exercise would increase the effects of p-cymene therapy. Finally, p-cymene has been shown to have a disaggregating effect on pre-formed amyloid fibrils, which could be of use in other forms of amyloidosis.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 1249 kb)

Data availability

All data is included in the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare to have no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval

Approval was received from the Islamic Azad University, Science and Research Branch Animal Ethics Committee.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Solanki I, Parihar P, Parihar MS. Neurodegenerative diseases: from available treatments to prospective herbal therapy. Neurochem Int. 2015;95:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drachman D. Aging of the brain, entropy, and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(8):1340–1352. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240127.89601.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duthey B. Alzheimer disease and other dementias,Priority Medicines for Europe and the World. A Public Health Approach to Innovation. 2004:1–74.

- 4.de Sousa DP, Gonçalves JCR, Quintans-Júnior L, Cruz JS, Araújo DAM, de Almeida RN. Study of anticonvulsant effect of citronellol, a monoterpene alcohol, in rodents. Neurosci Lett. 2006;401:231–235. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nerio LS, Olivero-Verbel J, Stashenko E. Repellent activity of essential oils: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:372–378. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quintans-Júnior LJ, Souza TT, Leite BS. Phythochemical screening and anticonvulsant activity of CymbopogonwinterianusJowitt (Poaceae) leaf essential oil in rodents. Phytomedicine. 2008;15:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang QG, Bi LW, Zhao ZD, et al. Application of ultrasonic spraying in preparation of p-cymene by industrial dipentenedehydrogenation. Chem Eng. 2010;159:190–194. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benchaar C, Calsamiglia S, Chaves AV, Fraser GR, Colombatto D, McAllister TA, Beauchemin KA. A review of plant-derived essential oils in ruminant nutrition and production. Anim Feed Sci Technol. 2008;145:209–228. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh HP, Kohli RK, Batish DR, Kaushal PS. Allelopathy of gymnospermous trees. J Forest Res. 1999;4:245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selvaraj M, Pandurangan A, Seshadri KS, Sinha PK, Krishnasamy V, Lal KB. Comparison of mesorporous A1-MCM-41 molecular sieves in the production of p-cymene for isopropylation of toluene. J Mol Catal A-Chem. 2002;186:173–186. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siani AC, Garrido IS, Carvalho ES, et al. Evaluation of antiinflammatory- related activity of essential oils from the leaves and resin of species of Protium. J Ethnopharmacol. 1999;66:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00148-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonjardim LR, Cunha ES, Guimarães AG. et al. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C 2012;67:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Jullyana de Souza SQ, Paula PM, Márcio Roberto VS, et al. Improvement of p-cymene antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects by inclusion in _-cyclodextrin. Phytomedicine. 2013;20:436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li JZ, Liu CZ. S T. Novel antitumor invasive actions of p-cymene by decreasing MMP-9/ TIMP-1 expression ratio in human Fibrosarcoma HT-1080 cells. Pharmaceutical Soci Japan Biol Pharm Bull. 2016;39:1247–1253. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b15-00827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickavar B, Adeli A, Nickavar A. TLC-bioautography and GC-MS analyses for detection and identification of antioxidant constituents of trachyspermum copticum essential oil. Iran J Pharm Res: IJPR. 2014;13(1):127–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yvon Y, Guy Raoelison E, Razafindrazaka R et al. Relation between chemical composition or antioxidant activity and antihypertensive activity for six essential oils. J Food Sci 2012;77:H184–H191. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Zhang H, Ma Q, Zhang Y, Xu H. Proteolytic processing of Alzheimer s β-amyloid precursor protein. JNeurochem. 2012;120(1):9–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Larson EB, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, Kim JS, Heo S, Alves H, White SM, Wojcicki TR, Mailey E, Vieira VJ, Martin SA, Pence BD, Woods JA, McAuley E, Kramer AF. Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(7):3017–3022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015950108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yaghmaei P, Azarfar K, Dezfulian M, Ebrahim-Habibi A. Silymarin effect on amyloid-β plaque accumulation and gene expression of APP in an Alzheimer’s disease rat model. DARU J Pharmaceutical Sci. 2014;22(1):24. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-22-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu N-W, Smith IM, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ. Soluble amyloid-β peptides potently disrupt hippocampal synaptic plasticity in the absence of cerebrovascular dysfunction in vivo. Brain. 2008;131(9):2414–2424. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates: hard cover edition. The Netherlands: Academic Press, Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guaza C, Borrell J. Prolonged ethanol consumption influences shuttle box and passive avoidance performance in rats. Physiol Behav. 1985;34(2):163–165. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(85)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosseinzadeh S, Dabidi Roshan V, Pourasghar M. Effects of intermittent aerobic training on passive avoidance test (shuttle box) and stress markers in the dorsal Hippocampus of Wistar rats exposed to Administration of Homocysteine. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci. 2013;7(1):37–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gandy S. The role of cerebral amyloid beta accumulation in common forms of disease. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1121–1129. doi: 10.1172/JCI25100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marklund S, Marklund G. Involvement of the superoxide anion radical in the autoxidation of pyrogallol and a convenient assay for superoxide dismutase. Eur J Biochem. 1974;47(3):469–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1974.tb03714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kappus H. Lipid peroxidation: mechanisms, analysis, enzymology and biological relevance. Oxidative stress. 1985;1:273. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoveida R, Alaei H, Oryan S, et al. Effects of exercise on spatial memory deficits induced by nucleus basalismagnocellularis lesions. Physiol Pharmacol Article in Persian. 2009;13(3):319–327. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghobeh M, Ahmadian S, Meratan AA, Ebrahim-Habibi A, Ghasemi A, Shafizadeh M, Nemat-Gorgani M. Interaction of Aβ (25–35) fibrillation products with mitochondria: effect of small-molecule natural products. Pept Sci. 2014;102(6):473–486. doi: 10.1002/bip.22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cetin F, Dincer S. The effect of intrahippocampal beta amyloid (1-42) peptide injection on oxidant and antioxidant status in rat brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100(1):510–517. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S, Wang P, Liliren, et al. Protective effect of melatonin on soluble Aβ1–42-induced memory impairment, astrogliosis, and synaptic dysfunction via the Musashi1/Notch1/Hes1 signaling pathway in the rat hippocampus. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Majd S, Power JH, Grantham HJM. Neuronal response in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease: the effect of toxic proteins on intracellular pathways. BMC Neurosci. 2015;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12868-015-0211-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yaghmaei P, Kheirbakhsh R, Dezfulian M, Haeri-Rohani A, Larijani B, Ebrahim-Habibi A. Indole and trans-chalcone attenuate amyloid β plaque accumulation in male Wistar rat: in vivo effectiveness of two anti-amyloid scaffolds. Arch Ital Biol. 2013;151(3):106–113. doi: 10.4449/aib.v151i3.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bag S, Ghosh S, Tulsan R, Sood A, Zhou W, Schifone C, Foster M, LeVine H, III, Török B, Török M. Design, synthesis and biological activity of multifunctional α, β-unsaturated carbonyl scaffolds for Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23(9):2614–2618. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.02.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Habtemariam S. Iridoids and other monoterpenes in the Alzheimer’s brain: recent development and future prospects. Molecules. 2018;23(1):117. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Sousa DP. Analgesic-like activity of essential oils constituents. Molecules. 2011;16:2233–2252. doi: 10.3390/molecules16032233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guimarães AG, Quintans JSS, Quintans-Júnior LJ. Monoterpenes with analgesic activity-a systematic review. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1–15. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tuppo EE, Arias HR. The role of inflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;37:289–305. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munoz L, Ammit AJ. Targeting p38 MAPK pathway for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:561–568. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bona D, Plaia A, Vasto S, et al. Association between the interleukin 1beta polymorphisms and Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta analysis. Brain Res Rev. 2008;59:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Griffin WS, Mrak RE. Interleukin 1 in the genesis and progression of and risk for development of neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. J Leukocy Biol. 2002;72:233–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lukiw WJ. NF-κB-regulated, proinflammatory miRNAs in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2012;4(6):47. doi: 10.1186/alzrt150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valerio A, Boroni F, Benarese M, Sarnico I, Ghisi V, Bresciani LG, Ferrario M, Borsani G, Spano PF, Pizzi M. NF-κB pathway: a target for preventing β-amyloid (Aβ)-induced neuronal damage and Aβ42 production. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(7):1711–1720. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sung S, Yang H, Uryu K, Lee EB, Zhao L, Shineman D, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY, Praticò D. Modulation of nuclear factor-κB activity by indomethacin influences Aβ levels but not Aβ precursor protein metabolism in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(6):2197–2206. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63269-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Walsh DM, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ, Anwyl R. Block of long-term potentiation by naturally secreted and synthetic amyloid β-peptide in hippocampal slices is mediated via activation of the kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as well as metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. J Neurosci. 2004;24(13):3370–3378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, Zhao L, Zhang C, Lan Z. Protective effect of p-cymene on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung InjuryinMice. Inflammation. 2014;37:358–364. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong W, Chi G, Jiang L, et al. p-Cymene modulates in vitro and in vivo cytokine production by inhibiting MAPK and NF-κB activation.Inflammation. 2013;36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Ono K, Yoshiike Y, Takashima A, Hasegawa K, Naiki H, Yamada M. Potent anti-amyloidogenic and fibril-destabilizing effects of polyphenols in vitro: implications for the prevention and therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2003;87(1):172–181. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adlard P, Perreau V, Pop V, Cotman CW. Voluntary exercise decreases amyloid load in a transgenic model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4217–4221. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akhavan M, Emami-Abarghoie M, Sadighi-Moghaddam, et al. Hippocampal angiotensin II receptors play an important role in mediating the effect of voluntary exercise on learning and memory in rat. Brain Res 2008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Tillerson J, Caudle W, Reverson M, et al. Exercise induced behavioral recovery and attenuates neurochemical deficits in rodent models of Parkinson’sdisease. Neuroscience. 2003;119(3):899–911. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore KM, Girens RE, Larson SK, Jones MR, Restivo JL, Holtzman DM, Cirrito JR, Yuede CM, Zimmerman SD, Timson BF. A spectrum of exercise training reduces soluble Aβ in a dose-dependent manner in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;85:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 1249 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All data is included in the manuscript.