Abstract

Objective (s)

Diabetes is the most common metabolic disease with an increasing prevalence throughout the world due to the changes in lifestyle. Appropriate self-care promotes the life condition of people with chronic illnesses and reduces the side effects of such diseases, so this study was designed to develop a scale for evaluating self-care in middle-aged patients diabetes.

Methods

In this methodological study, the following 4 steps were conducted for design and psychometric measurement of the questionnaire: 1) Data collection was carried out during a supplementary cross-sectional survey of the qualitative study; 2) determining the face validity (the assessment of facility, difficulty, and ambiguity of the items and their importance for patients) and content validity of the questionnaire (the assessment of appropriateness and necessity of items by experts opinions and measuring CVR and CVI; 3) the internal consistency of the questionnaire was evaluated by determining the Cranach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.85), and 4) test-retest of the scale with a 2-weeks interval confirmed appropriate stability for the scale (ICC = 0.81). The normality of data was also evaluated using skewness and kurtosis. CFA was performed using AMOS version 24 software.

Results

The first version of this questionnaire was produced with 71 items, of which 27 items were deleted during the process of validity and reliability confirmation. The final version of the questionnaire was provided with 44 items. For this study, 460 samples were used to examine the psychometric properties of the self-care scale.The confirmatory factor analysis showed a good fit to the data. Before the performing CFA, KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were evaluated and the results indicated an adequate sample (KMO = 0.956 and Bartlett’s test: χ2 = 14,288.048, df = 946, P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The findings showed that the designed questionnaire could assess self-care in patients with diabetes. This is a short, easy-to-use questionnaire that helps you understand what the patient needs to perform self-care behaviors.

Keywords: Diabetes, Self-care, Assessment tool

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most common disabling complications that are chronic and intangible and it has an increasing prevalence [1, 2]. At present, about 135 million people worldwide are diagnosed with diabetes, which is predicted to rise to 366 million by the year 2030, according to estimates by the World Health Organization [3]. At present, 3–5% of our population (about 3 million people) have diabetes [4].

In type 2 diabetes, drug therapy does not affect improving disease. More than 95% of the treatment process is performed by the patient, and the treatment team has little control over the disease between visits [5]. Therefore, the term comprehensive care is used to treat this disease. Note that diabetes treatment is something more than the control of glucose and personality-psychological-social factors should be considered [6]. Prevention of diabetes is largely dependent on the individual’s willingness to self-management and self-care [7, 8].

Diabetes self-management is strongly influenced by psychosocial factors such as diabetes, social support, self-efficacy, belief in treatment effectiveness, and constructive relationship with the physician [9, 10]. And the primary responsibility for care and treatment in a diabetic patient is with the individual himself. The World Health Organization (WHO) has reported the adherence to this behavior by patients in developed countries 50% and in developing countries less than 50% [11]. Increasing patients’ confidence in their ability to care for the disease is the main factor in active self-management of this disease [12, 13].

One of the most important challenges in this field is the identification of effective factors in the self-care of diabetic patients [14].

According to the aforementioned findings and the importance of which stage the individual is placed in self-care behaviors and disease and the role of awareness in planning and performing interventions to control the symptoms of diabetes, existing a valid tool that modulates self-care behaviors (Nutrition, blood sugar measurement, exercise, and so on) in the research and clinical trials are very necessary, as long as the researcher has found that there is no instrument to measure this structure in the country. The purpose of this study is the investigation of psychometric components of the Self-Care Behavior Scale (Internal reliability, test-retest reliability, concurrent validity, and construct validity) derived from Iran’s cultural, social context with a grounded theory approach on the process of self-care behavior formation in diabetic patients.

Materials and methods

Setting

The study setting was the specialist diabetes clinic of a private and public hospital located in Mashhad city.

Study design

Data collection was carried out during a supplementary cross-sectional survey of the qualitative study (Explaining the Process of Self-Care Behavior Formation in Diabetic Patients: A Grounded Theory Study) (Identifier: 961749), approved by the Ethics Committee of the State Medical Chamber of Mashhad. Written informed consent was obtained before participation.

Sample size

For this study, 460 samples were used to examine the psychometric properties of the self-care scale. Inclusion criteria for all samples were 1) age > 25 years and 2) having type 1and 2 diabetes.

Instruments

The sense of being disease scale based on sub-scales of (perceiving symptoms of the disease, coping with disease, treatment of symptoms, individual factors such as information and self-confidence) included 15 items and the temporary active care scale based on the subscales (comprehensive perturbation, sensitivity to disease, primary disease management, individual factors such as hope) including 13 items, passive care scale based on sub-scales (doubt to improvement, nature of the disease, management dependence to disease, supporting relatives) including 23 items, living with the disease based on sub-scales (Healthy claim of living, acceptance of the disease, self-management, sustainable self-care until the abandonment of disease, individuals factors such as self-reliance) including 20 items was designed with Likert scale. Finally, the initial questionnaire with 71 items was designed and its face and content validity were evaluated.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. All the participants consented to be their voices recorded, and the information they provided was kept confidential.

Validation: face and content validities

Qualitative formal validity

The formal validity of evaluating people’s perceptions of a tool provides an objective judgment of its acceptability and indicates that the tool designed will measure exactly the issue for which it was designed [15]. By surveying patients about “difficulty in understanding concepts”, “proportion and relationship” and “ambiguity and misunderstandings”, the face validity of the items was investigated and by assessing the effect of each item on a 5-point Likert questionnaire, the quantitative face validity can be calculated and the effect is equal to 1.5 or greater than the acceptable [16].

Qualitative content validity

Qualitative content validity was assessed based on the criteria of “grammar observance”, “use of appropriate words”, “items in their proper place” and “appropriate scoring” [16], and all items were reviewed and recommendations of the expert group was applied in the initial questionnaire.

Quantitative content validity was calculated using the content validity ratio and content validity index. To determine the content validity ratio, the group of experts was asked to assess each item using a three-part questionnaire consisting of items: 1 = necessary, 2 = useful but unnecessary 3 = unnecessary. Subsequently, according to Lawshe table [17], items with a CVR of 0.5 or higher were selected [16]. To determine the content validity index, the experts investigated the items based on Waltz and Basel [18, 19] according to a 3-point scale, related to “specificity”, “clear and transparent” and “easy and fluency”. The content validity index of 0.8 or higher indicates the appropriateness of the content validity of the tool [19].

Content validity was used by a panel of experts (10 health education specialists, 15 specialists, physicians, psychologists, nutritionists, nurses working with diabetic patients) to determine Scientific trust.

After completing the above steps, the pre-final questionnaire was designed and the next steps including determining the construct validity and reliability of the Cronbach’s alpha questionnaire were performed.

Construct validity assessment (exploratory factor analysis)

Firstly, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO > 0.8) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (<0.05) were used to make sure of the reliability of sampling [20]. CFA was used to evaluate the Construct validity assessment. Before to CFA, data were analyzed using Mahalobis statistics for the outliers. The normality of data was also evaluated using skewness and kurtosis. CFA was performed using AMOS version 24 software. To obtain an acceptable model, questions with poor internal consistency were removed from the questionnaire.

The assessment of the model was conducted using the following fit indices: Chi-square ratio to the degree of freedom (×2/df); root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA); parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI); parsimony comparative fit index (PCFI); incremental fit index (IFI); and comparative fit index (CFI) [21, 22]. The model was acceptable if the (×2/df) <5, RMSEA ≤0.08, PCFI and PNFI>0.5, IFI and CFI > 0.9 [23].

Psychometrically evaluate

A cross-sectional study was carried out to psychometrically evaluate the questionnaire and the sample was selected randomly from several comprehensive health centers and diabetes center of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. Inclusion criteria included: definitive diagnosis of diabetes in the file with the approval of a specialist physician, at least six months after diagnosis, and the patient’s willingness to share his or her experiences.

A questionnaire was measured using confirmatory factor analysis, in this type of factor analysis; the ratio of 5 to 1 or 4 to 1 for sample size is recommended [24]. At this stage, to collect 460 necessary samples are selected, sample selection criteria: People with type 2 diabetes referred to diabetes clinics in Mashhad in 2010 that selected as a quarto. The diagnosis was based on the physician’s opinion of the clinic and record in a file. Confirmatory Factor Analysis using Amos software was used to determine fitness.

Measure the reliability

Internal consistency and test-retest methods were used to measure the reliability of the designed tool. Internal consistency is the consistency of the results of the tool items [15]. A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used for measuring the internal consistency of the tool, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of greater than 0.7 means that the questionnaire has acceptable reliability [25].

In this study, to check the consistency of the questionnaire, the test-retest method was used. Test-retest is the completion of a tool by a group of samples under the same conditions at two or more different time situations [15]. To determine the coefficient of test-retest of a tool, 20 subjects were selected statistically and completed the questionnaire for the second time with a two-week interval. The test-retest reliability between the scores obtained using the ICC was calculated and values higher than 0.4 were accepted [26].

Findings

In the qualitative part of the research, after conducting in-depth interviews with 28 participants (21 main participants, 4 members of the medical staff including physicians and nurses and 3 different family members), the richness and saturation of the data were obtained. They ranged in age from 31 to 60 years with demographic characteristics as described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants

| Characteristics of contributors | Qualitative section | Quantitative section | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | ||

| Gender | Man | 13 | 46.4 | 175 | 38.5 |

| Female | 15 | 53.6 | 285 | 61.5 | |

| Age | 25–39 | 11 | 39.3 | 31 | 6.7 |

| 40–49 | 8 | 28.5 | 148 | 32.1 | |

| 50–59 | 9 | 32.2 | 156 | 33.9 | |

| 60 and above | 0 | 0 | 125 | 27.1 | |

| education | Under the diploma | 5 | 17.9 | 297 | 64.5 |

| Diploma and higher than a diploma | 11 | 39.3 | 158 | 34.4 | |

| Bachelor’s degree and higher | 12 | 42.8 | 5 | 1.1 | |

In the quantitative part of the study, 460 patients were included in the study for confirmatory factor analysis. The age of patients participating in the study was 35–64 years with a mean age of 52–9. The majority of participants in this study were female (61%), married people (89%), high school and diploma graduates (51%) and diagnosis in 60% of people over 40 years was proved. Most people had regular visits to the doctor (62%), 34% had a history of hospitalization due to diabetes, and 60% had taken pills (Table 1).

To determine the qualitative content validity, suggestions made by the experts applied in the questionnaire. Quantitative content validity was determined by determining the content validity ratio and content validity index.

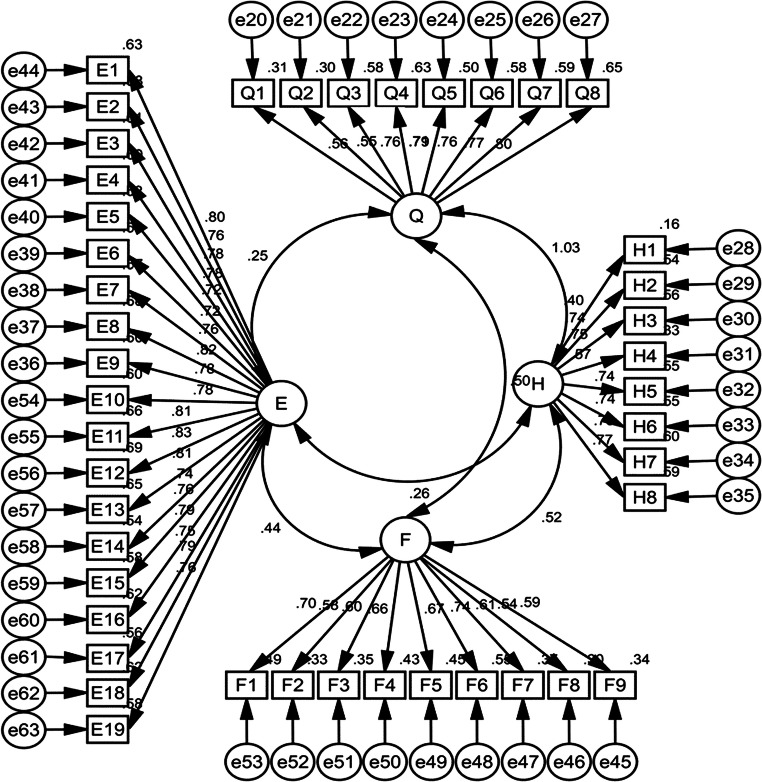

In investigating the content validity index (CVI), items that its content validity index was less than 0.8 were excluded from the questionnaire. In investigating the content validity ratio (CVR): given that there were 20 members of the expert group, the items that its content validity was less than 0.5 were excluded according to the formula and Lawshe table. In investigating the quantitative face validity, since the impact of all items was high, all items were retained and diagnosed for proper analysis. In investigating the qualitative face validity, by asking patients about specific indices, the cases considered were applied in the questionnaire. To evaluate the construct validity after making the necessary changes according to the previous steps, a questionnaire with 44 items was designed which was submitted to six experienced professors for consideration and receiving the final opinion and considering that the professors considered the questionnaire acceptable, construct validity using confirmatory factor analysis was investigated and finally, reliability of the tool was investigated (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis results of the designed tool

It can be seen from the data in the table that the scores obtained from the two tests performed with an interval of 10 days for 20 patients with diabetes had a good internal consistency (Table 2).

Table 2.

Internal and external reliability of the questionnaire used in the study

| Questionnaire variables | External reliability Cronbach’s alpha |

Internal reliability Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Feeling sick | 0/81 | 0/80 |

| Active care | 0/80 | 0/78 |

| Passive care | 0/78 | 0/79 |

| Living with illness | 0/79 | 0/77 |

For confirmatory factor analysis at this stage, 460 patients with diabetes were randomly selected and after filling out questionnaires, confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the hypothesis of factor structure and to determine the validity of the designed tool construct. The indicators obtained from the confirmatory factor analysis are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients table by scales

| Subscale | Items | Mean | SD | Range | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feeling sick | 8 | 10.15 | 3.64 | 8–40 | 0.89 |

| Active care | 9 | 11.34 | 3.42 | 9–45 | 0.85 |

| Passive care | 19 | 28.41 | 13.74 | 19–95 | 0.96 |

| Living with illness | 8 | 10.06 | 3.41 | 8–40 | 0.87 |

Table 4.

Models’ evaluation overall fit measurements

| Goodness of fit indices | Confirmatory factor analysis |

|---|---|

| X2 | 2679.960 |

| Df | 896 |

| X2/df | 2.991 |

| p value | <0.001 |

| CFI | 0.91 |

| RMSEA | 0.066 |

| PNFI | 0.775 |

| PCFI | 0.825 |

| IFI | 0.91 |

Construct validity assessment (CFA) Before the performing CFA, KMO and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were evaluated and the results indicated an adequate sample (KMO = 0.956 and Bartlett’s test: χ2 = 14,288.048, df = 946, P < 0.001). Since the amount of distance is more than 0.8 and the zero hypotheses of Bartlett’s test of sphericity in the 5% error level was confirmed, the reliability acceptable if the sample size could be verified [20].

As can be seen in the above table, almost all the model fit indices were within an acceptable range, and confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the validity of questionnaire constructs. Reliability analysis of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to 0.85 indicated good internal consistency of the tool and showed ICC equivalent to tool stability (Table 5).

Table 5.

Models’ evaluation scales fit measurements

| Subscale | Items | Standardized regression weights |

|---|---|---|

| Scale (feeling sick) | Before diagnosing my disease, I didn’t know much about the complications of diabetes. | 0.557 |

| Before diagnosing my illness, I didn’t know much about diabetes self-care behaviors. | 0.549 | |

| I see fear and anxiety as a consequence of the disease in diabetic patients. | 0.762 | |

| After diagnosis, I sought treatment for the disease. | 0.792 | |

| After learning about the complications of diabetes, I found myself at risk for complications. | 0.710 | |

| After seeing the symptoms of the disease and its persistence, I seek treatment for the symptoms. | 0.762 | |

| I have a hard time believing diabetes and its complications. | 0.769 | |

| Before I was diagnosed with diabetes, I didn’t care about my health. | 0.803 | |

| Scale (Temporary Active Care) | Being aware of the side effects of the disease increased my motivation for self-care behavior. | 0.700 |

| Because of my fear of the complications of the disease, my desire to practice self-care increased. | 0.578 | |

| By observing the side effects of the disease in other patients, I follow my doctor’s advice. | 0.595 | |

| At the time of our diagnosis, I was regularly referred to a doctor. | 0.656 | |

| At the beginning of our diagnosis, I followed my diet as prescribed by my doctor. | 0.668 | |

| At the start of our diagnosis, I exercised daily and regularly. | 0.742 | |

| At the beginning of our diagnosis, I regularly attended diabetes counseling classes. | 0.608 | |

| After a period of self-care behaviors, I doubted the impact of the doctor’s recommendations on improving our patients. | 0.545 | |

| With the prolongation of my illness, I concluded that self-care behaviors did not affect my recovery. | 0.587 | |

| Scale (passive care) | As my illness got longer, my self-care behaviors became boring. | 0.797 |

| Following the doctor’s recommendations does not have any effect on the improvement of the disease. | 0.762 | |

| I think home remedies and local remedies have a greater impact on our patient’s treatment than prescription medications. | 0.781 | |

| I do not take my medication regularly and as directed by a physician. | 0.777 | |

| Forcing my family to keep me on a diet. | 0.722 | |

| I get motivated by encouraging others to exercise. | 0.717 | |

| It is difficult for me to exercise without the presence of others alone. | 0.757 | |

| I follow my diet in the presence of others. | 0.825 | |

| Proximity to health centers affects regular visits to physicians and participation in diabetes counseling classes. | 0.775 | |

| Healthy whole foods are important in keeping a diet. | 0.777 | |

| Access to parks and sports equipment is important for regular physical activity. | 0.811 | |

| I think the contents of the diabetes counseling classes are repetitive and have no effect on my knowledge. | 0.830 | |

| The presence of a person with scientific information about diabetes in the family and relatives is helpful for self-care behaviors. | 0.808 | |

| Proper weather conditions are important for self-care behaviors. | 0.737 | |

| It is difficult for me to observe self-care behaviors under certain circumstances, such as travel and Ramadan and partying | 0.762 | |

| The economic and expensive problems cause me not to follow the diet. | 0.786 | |

| Occupation and work-related stress make me not self-care. | 0.750 | |

| Diabetes is an inherited disease and does not have full prevention and treatment. | 0.786 | |

| There are a large courtyard and a nearby park to encourage you to exercise. | 0.765 | |

| Scale (Living with Disease) | I’m happy with my diet. | 0.400 |

| I feel good when my blood sugar test is balanced. | 0.736 | |

| I observe self-care in all situations (at any time and place). | 0.750 | |

| Attending class and seeing a doctor is useless. | 0.573 | |

| I have so experimentally adjusted my blood sugar that I don’t need to see a doctor. | 0.744 | |

| I’m tired of dieting and exercising daily. | 0.743 | |

| I am saddened to hear the advice and opinions of others about my illness. | 0.778 | |

| Exercising and following a diet at every meal increases my motivation to continue doing so. | 0.767 |

Discussion

Adopting self-care in diabetes is always a challenging issue for both patients and physicians and health care providers. Self-care is defined as a decision-making process where behaviors can maintain physiological balance and, if symptoms occur, the patient can manage these complications [27].

Anbari et al. [28], Kordi et al. [29], Mo′ in et al. [30] performed the research samples of self-care behaviors in a moderate limit. Also, Jordan and colleagues’ study about self-care behaviors in diabetic patients in the United States showed that patients’ self-care status was moderately desirable [31]. But in Mazlum and Parham’s study, self-care of the studied samples was reported poor and undesirable; self-care and patient cooperation have the most important factors in controlling diabetes and preventing its complications. It shows that diabetic patients do not have a good self-care score in many areas contrary to the high importance of self-care [32, 33].

Interventions by health care providers and physicians seem to be ineffective in this regard and given that the concept of self-care is formed in the interactions and social interactions of individuals it is hidden in social interactions and is crystallized. It is possible to experience and understand this phenomenon only through grounded theory. By conducting this research, we designed a tool to remove patients’ problems and barriers by understanding the patients’ stage of the disease by adopting effective intervention strategies. Therefore, the main purpose of the present study was to investigate the psychometric properties of a tool for explaining the formation process of adopting self-care behavior in diabetic patients. Variance value was acceptable and represented the main features of the subject [34].

After developing a tool, to estimate total internal consistency and different domains of the tool, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated and the internal consistency of the final design tool indicated that due to the proximity of the alpha value to one, the reliability is confirmed. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient appropriate in any area indicates that items of that field are well represented from the content of that dimension [35] and this is confirmed about the tool. Besides, a test-retest test was used to determine instrument stability for 2 weeks on 20 patients. The Pearson correlation coefficient does not confirm the stability of the developed tool.

In most studies, if the test used for research purposes has a reliability coefficient of 0.70 to 0.80, it seems sufficient. Nonna also believes that for the rapid judgment on the intrinsic correlation results, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are acceptable more than 0.70 and the results can be accepted between 0.60 and 0.699, especially if it can increase the correlation coefficient by removing one or several issues [36].

Overall, the reliability findings indicated that all four of the questionnaire subscales had acceptable internal consistency coefficient.

The values of the goodness of fit indices in the confirmatory factor analysis indicated the validity of the construct of this questionnaire and showed that the questions were appropriately categorized and that the tool was reliable, indicating increasing study ability for identifying significant relationships and differences in the study [34].

The result of the present study was designed with 44 items titled “Assessment Tool of Self-Care Behavior in Diabetic Patients” and by analyzing the data of this study, content validity, face validity, construct validity, internal consistency and it’s proof were approved. This questionnaire is a simple and objective tool for assessing the self-care behavior of patients with diabetes, and understanding in which stage of disease and beliefs are the patients about adopting self-care behaviors, it can be considered a more appropriate approach to adopt a self-care behavior for them.

One of the limitations of this study is that due to the impact of cultural, economic and social conditions on patients’ self-care behavior, it was tried the samples to be in the average level of cultural, economic and social status.

Conclusion

Self-care in diabetic patients is a mental, interactive, multidimensional process and is influenced by cultural and social factors and it is formed in the context of society, which can be explained in the cultural context of any society with qualitative studies and this questionnaire can be a useful tool for measuring and the reasons for doing or not doing self-care behavior in patients with diabetes. This study indicates that the tool has desirable validity and reliability for evaluating self-care behavior in diabetic patients.

By completing this questionnaire, it is determined at what stage of the patient’s self-care behaviors and based on it, effective and timely intervention strategies can be considered to solve patients’ problems and obstacles in adopting self-care behavior through education and support programs.

Limitations and future research

Patient concerns were considered to complete the research and optimize the interviews. At the start of the interview, participants were asked about when they would be interviewed and whether they were bored at the time; And the timing of the next interview would be a poll. The ethics of the research were sought to be kept confidential. Future research is needed to provide greater insights into patients’ self-care behaviors and practices in all contexts.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude and appreciation to all respected professors, clinics, comprehensive health centers and participants in this study, and we wish God the best for each of these dear ones. The authors thanks to the many colleagues whose vignettes about dilemmas of improving quality shaped this paper, and the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Funding information

Financial support was received from the Mashhad University of Medical Science.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is based on a research project approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences with the code of ethics IR.MUMS.REC.1398.006 All procedures performed in this study were under the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable.

All project participants were informed of the project goals before the interview and have completed a written consent form and they have been assured of confidentiality. This research project is funded by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

All project participants were informed of the project goals before the interview and have completed a written consent form and they have been assured of confidentiality.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Davood RobatSarpooshi, Email: Robatsd951@mums.ac.ir.

Ali Taghipour, Email: taghipourA@mums.ac.ir.

Mehrsadat Mahdizadeh, Email: msmahdizadeh@gmail.com.

Saki Azadeh, Email: SakiA@mums.ac.ir.

Jafari AliReza, Email: jafari.ar94@gmail.com.

Nooshin Peyman, Email: peymann@mums.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Ding CH, Teng CL, Koh CN. Knowledge of diabetes mellitus among diabetic and non-diabetic patients in Klinik Kesihatan Seremban. Med J Malaysia. 2006;61(4):399–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Connell S, Smeltzer C, Bare B, Hinkle JL, Cheever KH. Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing, vol. 1. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- 3.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(5):1047–1053. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esteghamati A, Etemad K, Koohpayehzadeh J, Abbasi M, Meysamie A, Noshad S, et al. Trends in the prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in association with obesity in Iran: 2005-2011. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 103(2):319–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Vinter-Repalust N, Petricek G, Katic M. Obstacles which patients with type 2 diabetes meet while adhering to the therapeutic regimen in everyday life: qualitative study. Croat Med J. 2004;45(5):630–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denis K. Principles of internal medicine of Harrison endocrinology and metab. Thehran: Teimoorzade publication; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer JA, Koszewski WM, Jones GM, Stanek-Krogstrand K. The use of interviewing to assess dietetic internship preceptors needs and perceptions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(8):A48. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.05.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fitzgerald JT, Gruppen LD, Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Jacober SJ, Grunberger G, Aman LC. The influence of treatment modality and ethnicity on attitudes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(3):313–318. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDowell J, Courtney M, Edwards H, Shortridge-Baggett L. Validation of the australian/english version of the diabetes management self-efficacy scale. Int J Nurs Pract. 2005;11(4):177–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlstedt RA. Handbook of integrative clinical psychology, psychiatry, and behavioral medicine: perspectives, practices, and research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubkin IM, Larsen PD. Chronic illness: impact and interventions. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonseca V, Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2572–2573. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu D, Fu H, McGowan P, Shen Y-E, Zhu L, Yang H, et al. Implementation and quantitative evaluation of chronic disease self-management programme in Shanghai, China: randomized controlled trial. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:174–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang TS, Funnell MM, Brown MB, Kurlander JE. Self-management support in “real-world” settings: an empowerment-based intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 79(2):178–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Fitzner K. Reliability and validity a quick review. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(5):775–780. doi: 10.1177/0145721707308172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajizadeh E, Asghari M. Statistical methods and analyses in health and biosciences a research methodological approach. Tehran: Jahade Daneshgahi Publications. p. 395.

- 17.Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity 1. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–575. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: design statistics and computer analysis: Davis FA; 1981.

- 19.Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–497. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaiser HF, Rice J. Little jiffy, mark IV. Educ Psychol Meas. 1974;34(1):111–117. doi: 10.1177/001316447403400115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henry JW, Stone RW. A structural equation model of end-user satisfaction with a computer-based medical information system. Inf Resour Manag J (IRMJ) 1994;7(3):21–33. doi: 10.4018/irmj.1994070102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lomax RG, Schumacker RE. A beginner's guide to structural equation modeling. London: Psychology Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res. 2006;99(6):323–338. doi: 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(3):286–299. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider Z. Nursing research: an interactive learning. London: Mosby Co.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumgartner TA, Chung H. Confidence limits for intraclass reliability coefficients. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2001;5(3):179–188. doi: 10.1207/S15327841MPEE0503_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter-Edwards L, Skelly AH, Cagle CS, Appel SJ. “They care but don’t understand”: family support of African American women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30(3):493–501. doi: 10.1177/014572170403000321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anbari K, Ghanadi K, Kaviani M, Montazeri R. The self care and its related factors in diabetic patients of khorramabad city. Yafteh. 14(4):49–57.

- 29.Kordi M, Banaei M, Asgharipour N, Mazloum SR, Akhlaghi F. Prediction of self-care behaviors of women with gestational diabetes based on Belief of Person in own ability (self-efficacy). Iran J ObstetGynecol Infertil. 19(13):6–17.

- 30.Moeini B, Teimouri P. Haji Masoudi S, Afshari M, Moghadam M, et al. Analyse of self-care behaviours and its related factors among diabetic patiants Qom Univ Med Sci J.10(4):48–57.

- 31.Nouhjah S. Self-care behaviors and related factors in women with type 2 diabetes. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 16(6):393–401.

- 32.Mazlom SR, Firooz M, Hoseini SJ, Hasanzadeh F, Kimiaie SA. Self-care of patient with diabetes type II.

- 33.Parham M, Rasooli A, Safaeipour R, Mohebi S. Assessment of effects of self-caring on diabetic patients in Qom diabetes association 2013.

- 34.DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and applications. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- 35.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 3st Editon. New York: Harpercollins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farrokhi A, Zareh Zadeh M, Karimi Alvar L, Kzaemnejad A, Ilbeigi S. Reliability and validity of test of gross motor development-2 (Ulrich, 2000) among 3-10 aged children of Tehran City. J Phys Educ Sport Manag. 5(2):18–28.