Abstract

Fecal incontinence is a prevalent health problem that affects over 20% of healthy women. Many surgical treatment options exist for fecal incontinence after attempts at non-operative management. In this article, the authors discuss surgical treatment options for fecal incontinence other than sacral neuromodulation.

Keywords: fecal incontinence, sphincter repair, injectables, colostomy

Fecal incontinence (FI) is a common problem, affecting almost 20% of healthy adult women and 8.6% of older men according to population-based studies. 1 2 3 Direct trauma to the anal sphincter or associated nerves during vaginal delivery are common causative factors contributing to FI. Up to 35% of women may experience injuries to the anal sphincter following vaginal delivery, even without visible signs of perineal injury. 4 5 Additional risk factors for both men and women include increasing age, postmenopausal hormonal changes, neurologic disorders, obesity, stool changes related to comorbidities, or prior surgical procedures including anorectal and other gastrointestinal-related operations such as cholecystectomy and bariatric surgery, and other physical changes including limitations in mobility. 6 Treatment options include lifestyle changes, medications, office-based procedures, and surgical procedures.

When evaluating a patient with complaints of FI, first steps include a detailed history of FI including frequency of incontinence, stool consistency (solid stool, liquid stool, gas only), ability to sense and defer bowel movements versus passive incontinence, quantity of incontinent stool, need for splinting, and medications used including bulking agents, antidiarrheal medications, and laxatives as well as medications for other medical conditions. A stool diary and validated incontinence scoring system such as the Wexner Cleveland Clinic Incontinence scale, Vaizey Incontinence Score, or colorectal functional outcome score will facilitate this history and provide objective evidence of improvement or failure to improve. 7 8 A comprehensive general medical and surgical history including anorectal procedures, obstetric history, and family history is obtained. If the patient is not up-to-date on screening colonoscopy or has experienced a change in bowel habits, a colonoscopy is typically recommended. A careful review of prior treatment approaches should be obtained including use of bulking and antimotility agents, physical therapy and biofeedback, and any other office-based or surgical procedures.

Office examination includes a comprehensive physical exam to determine fitness for possible surgical treatments, as well as perineal examination in either the left lateral decubitus or prone jackknife position. External examination, digital rectal exam, anoscopy, and often, examination on the commode are important aspects of the office examination. Attention is given to perineal skin integrity and scarring, tone, relaxation, masses, bleeding, and vaginal or anal prolapse with Valsalva, and a bimanual exam to evaluate for rectocele, enterocele, sigmoidocele, or cystocele. If there is concomitant middle or anterior compartment prolapse or urinary incontinence, referral to an urogynecologist should be made for comanagement of these concerns. Anoscopy can exclude distal rectal and anal canal pathology including proctitis, prolapse changes, and rectovaginal fistula that can contribute to incontinence. It can also be helpful to examine these patients on a commode with or without saline enema to evaluate for rectal prolapse. If rectal prolapse is observed, repair of the rectal prolapse should be performed prior to proceeding with therapy directed at FI.

Initial management of FI in the absence of rectal prolapse focuses on addressing stool consistency and pelvic floor strengthening and sensation. Continence may improve with these nonoperative interventions and stool consistency and attention to strength and sensation play an important role in success of more invasive interventions. Stools should be soft and formed to enable patients to sense more easily and control bowel movements. Addressing side effects of medications (e.g., metformin) or prior operations that can cause diarrhea (cholecystectomy) by adding bulking or antimotility agents can be helpful. Psyllium husk fiber adds bulk to stool while loperamide functions as an antimotility agent. Markland et al noted equal efficacy in improving FI and quality of life with either agent, but less side effects of constipation with psyllium husk fiber. 9 A referral should also be placed for a pelvic floor specialized physical therapist for pelvic floor and biofeedback therapy.

After at least 3 months of pelvic floor physical therapy and biofeedback with appropriate stool bulking, if the patient continues to have bothersome FI, more invasive treatment options can be considered. Further evaluation of anorectal function is obtained with anorectal physiology testing: anal manometry, electromyogram, endoanal ultrasound to evaluate for sphincter defects, and occasionally pudendal nerve terminal motor latency (PNTML) testing. PNTML testing has been applied most when considering the success of an overlapping sphincteroplasty. Mixed results are reported in the literature with some studies suggesting that prolonged PNTML portends worse function in patients undergoing overlapping sphincteroplasty, while other studies show no difference in outcomes. 10

In choosing a treatment approach, it is important to review patient's goals and expectations. Patients may report low FI severity scores with great impact on quality of life, while other patients may report high satisfaction with interventions while continuing to report high levels of FI. 11 It is important to note, that a previously incontinent patient may not regain perfect continence to solid stool, liquid stool, and gas with any intervention.

Sphincter Repair

In the setting of a sphincter defect less than 120 degrees, and particularly in younger patients with a recent sphincter injury, sphincteroplasty may be offered as a potential management option. Studies of multiple series of patients with FI indicate good success with improving continence particularly for solid stool and, to a lesser degree, liquid stool. Gas continence is much harder to improve and patients should be counseled as such. Additionally, improved continence does decrease with time and the majority of patients return to their baseline continence by 5 to 10 years postrepair. 12 13 Sphincteroplasty outcomes are not as good in older women who had a remote injury. Additionally, if a patient had a prior sphincteroplasty and they return with incontinence, outcomes of repeat sphincteroplasty are poor and alternative options such as sacral neuromodulation should be pursued. 14

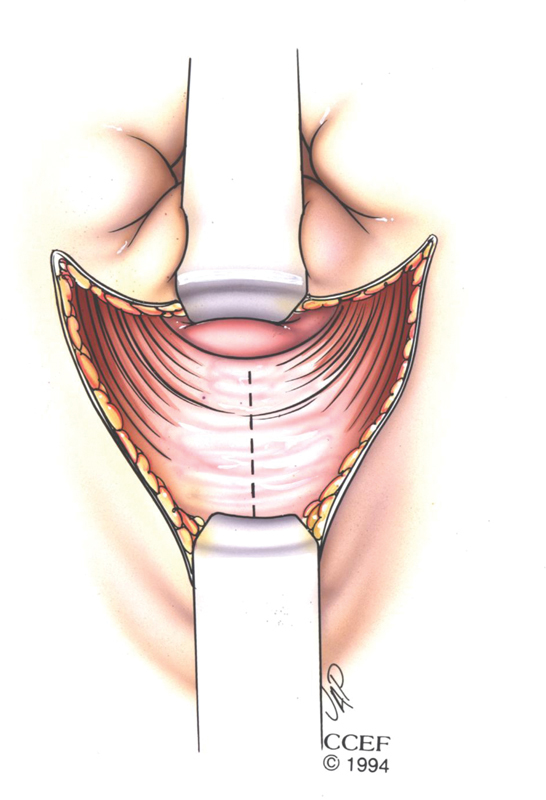

Sphincteroplasty is performed in the operating room. We prefer the prone jackknife position with general anesthesia. The patient is given a mechanical and oral antibiotic bowel prep. Intravenous antibiotics are administered in the operating room and a Foley catheter is sterilely placed. The buttocks are taped apart. The operative field is sterilely prepped and draped. A curvilinear incision in made over the perineal body ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Initial curvilinear incision for sphincter repair. Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography, © 1994.

Skin flaps are developed sharply toward the anal and vaginal sides and then laterally until the ischiorectal fat is reached. Care is taken not to dissect further laterally to avoid injury to the pudendal nerves. The anterior sphincter scar is divided ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Division of the anterior sphincter star. Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography, © 1994.

We prefer an en bloc overlapping sphincteroplasty. The side of the sphincter with better mobility is external. A 2–0 polydioxanone suture is used to place vertical mattress sutures—typically a total of 6 sutures (2 columns of 3 sutures) are used ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Placement of sutures for overlapping sphincteroplasty. Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography, © 1994.

The sutures are initially clamped and then sequentially tied down once all sutures are in place ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Completed overlapping sphincteroplasty. Reprinted with permission, Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art and Photography, © 1994.

The buttock tapes are released. The ischiorectal fat can be reapproximated with interrupted sutures to provide good bulk to the perineal body and alleviate some tension on the sphincter repair. The skin is closed after ensuring hemostasis with 4.0 monocryl subcuticular or 3–0 Vicyl vertical mattress sutures depending on surgeon preference. The middle of the incision can be left open for drainage or a small drain can be placed. The patient is kept in the hospital with a Foley, on clear liquids until bowel function resumes. At that point, the Foley is removed, and the patient is able to eat, ambulate, and is discharged home.

Sacral nerve stimulation can also be offered to this patient population and is the preferred treatment option for patients with sphincter defects greater than 120 degrees, with no sphincter defect, with remote sphincter injury, or in patients with poor tissue integrity (e.g., prior radiation). The details of sacral nerve stimulation are covered in a separate article.

Several other treatment options have been investigated and are detailed below. At the present time, many of these options are either not available in the United States or are no longer being produced. The Renew device and the Eclipse System are two devices that offer promise to patients who suffer from FI but who either prefer an office-based procedure or who are too high risk to undergo any type of anesthetic. Colostomy remains an option for patients with FI though most patients prefer to avoid colostomy unless all other options fail.

Other Treatments Currently Available in the United States

Vaginal Bowel Control System (Eclipse System, Pelvalon)

What It Is and How It Works?

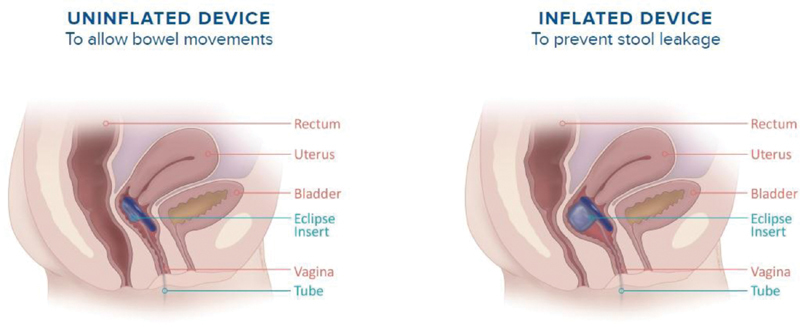

The Eclipse vaginal bowel control system is an inflatable vaginal insert with a pressure-regulated pump designed to occlude the rectum temporarily. The insert is placed in the vagina and contains a posteriorly directed balloon that can be inflated to occlude the rectum and deflated for defection ( Fig. 5 ). 15 16 17 There is a range of balloon and base sizes. The insert itself is a silicone-coated stainless steel base with the balloon. The Eclipse device is used for patients with ≥ 4 bowel accidents in a 2-week period and can be used in patients who have undergone hysterectomies.

Fig. 5.

Cartoon demonstrating eclipse vaginal bowel control system (used with permission from ref. 17).

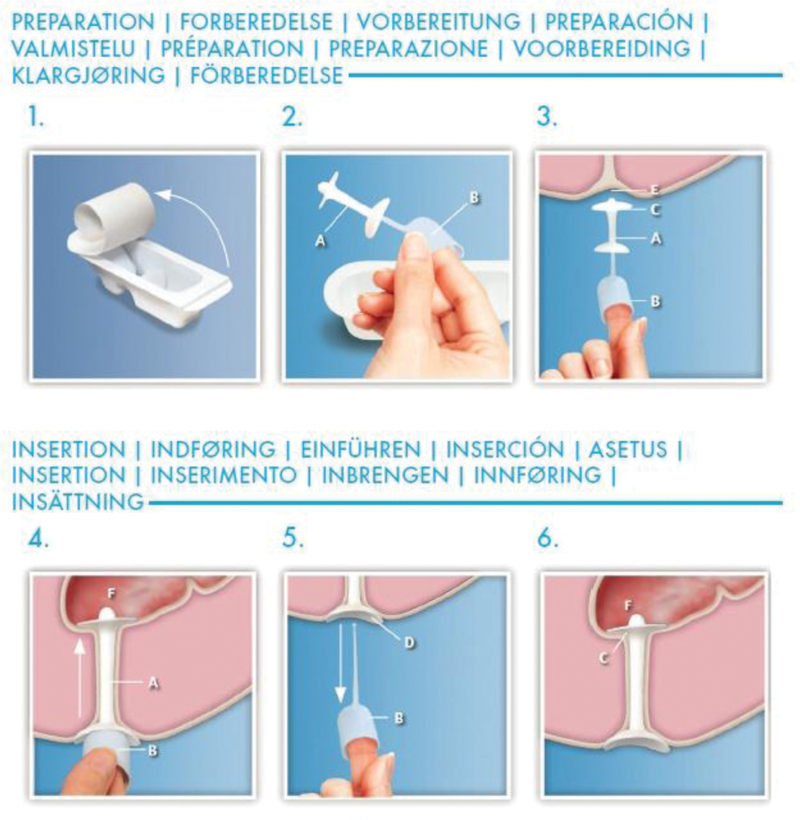

Fig. 6.

Cartoon demonstrating renew medical insert (used with permission from ref. 21).

The insertion technique involves measuring vaginal size and estimating the size of the insert using the sizing kit. The clinician then uses a trial insert to assess for fit and effectiveness at rectal occlusion. The clinician places the Trial Insert in the proximal vagina adjacent to the rectum. The clinician then uses the pressure-regulated pump to inflate the balloon, and a digital rectal exam confirms rectal compression. The patient uses the Trial Insert for approximately 1 to 2 weeks to assess for fit, comfort, and patient satisfaction. Following a successful trial insert, the clinician then places the Eclipse device. Patients are instructed to remove the Eclipse device once per week and clean both the device and the pump. The Eclipse device and the pump should be replaced yearly. 18 19 Contraindications to the Eclipse device include the presence of a vaginal infection or an open vaginal wound.

What Data Supports Its Use?

Richter Varma et al reported results from the LIFE Study in 2015. 16 This study was a trial to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the vaginally inserted bowel control device (Eclipse) for patients who experienced ≥ 4 bowel accidents in a 2-week period. The authors defined success as a ≥ 50% reduction in the number of bowel accidents assessed at 1 month. Secondary outcomes included symptom improvement measured by the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life (FIQOL), Modified Manchester Health Questionnaire, and Patient Global Impression of Improvement. A total of 110 patients were eligible over the 21-month study period with 61 (55.5%) undergoing a successful fit and entered treatment. Note that 78.7% of participants had a successful test based on intention-to-treat analysis. Moreover, there was improvement in the FIQOL and Modified Manchester Health Questionnaire. There were no major adverse events with the most common adverse event being cramping or discomfort in 22.7% of participants. Secondary analysis demonstrated reduction in bowel movement frequency and urgency and increased solid stool consistency and improved evacuation. 16 The investigators performed subsequent work evaluating the 12-month effect of the device in the LIBERATE Study and found that there was sustained success for participants that had successful fitting and initial treatment response. 20 Insurance coverage for the Eclipse device is currently challenging for many patients. There is also decreased availability of the device to many surgeons and patients ( Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 7.

Management algorithm for fecal incontinence.

Renew Medical Insert

What It Is and How It Works?

Renew Medical Insert (Renew Medical Inc., Foster City, CA) is a single-use, soft silicone plug that is inserted using an applicator that seals the anal canal until the patient's next bowel movement. The inserts come in two sizes: regular and large. The device is contraindicated in patients who are allergic to silicone or have undergone recent rectal surgery (within 4 weeks).

What Data Supports Its Use 22 ?

Lukacz et al reported the results of a 19-month study of adult patients with at least weekly incontinence of solid or liquid stool with Cleveland Clinic Florida Fecal Incontinence Scores (CCF-FIS) of 12 or greater. The trial involved continuous anal insert device (Renew) over a 12-week period with the primary outcome being a ≥ 50% reduction in the number of bowel accidents assessed weekly and the end of the study period. There were 73 completers and 18 noncompleters in the study (intention-to-treat: 91 patients). Sixty-two percent of the intention-to-treat subjects had a ≥ 50% reduction in the number of bowel accidents with the device. Mean FI severity scores improved from 16.2 ± 2.1 at baseline to 10.9 ± 4.4 after use ( p < 0.001). The majority of 73 completers were very or extremely satisfied with the device with no serious adverse events related to device use. The study itself is limited by a nonvalidated modification of the FI severity score, lack of control group, and blinding. The device is available from a medical device supplier in the U.S. following prescriber prescription. A box of 30 Renew devices costs around $100. It is unclear what the status of insurance coverage is for the device.

Treatments Currently Available Outside the United States

Dynamic/Nonstimulated Graciloplasty

What It Is and How It Works?

Graciloplasty as a treatment for sphincter dysfunction was first described in 1952 by Pickrell et al in a report of four children with intractable sphincter dysfunction. 23 In short, the procedure involves mobilizing and detaching the gracilis muscle from the tibial tuberosity while preserving the neurovascular bundle, encircling the anus, and attaching the muscle to the contralateral ischium. Further study of this technique over the next several decades demonstrated good success with the nonstimulated graciloplasty, although there was concern of gracilis muscle fatigue preventing sustained continence. 24 25 26 27 Given this concern, Baeten et al first described the use of a neurostimulator in a patient with previous graciloplasty to augment continence in 1988. 28 Further work from this group defined the procedure by completing the nonstimulated graciloplasty and then implanting the electrode leads after 6 weeks. 29 With electrical stimulation, the muscle changes from a type II fast-twitch to a type-I slow-switch, which is more resistant to fatigue. 30

What Data Supports Its Use?

Baeten et al found significant improvement of squeeze pressure and enema retention time with dynamic graciloplasty. Two multicenter trials have been performed evaluating dynamic graciloplasty, both finding that the majority of patients have success. 31 These groups and others have consistently found that the most frequent complications are infection, pain, and constipation and that the majority of patients have some complication. 32 33

GateKeeper/SphinKeeper

What It Is and How It Works?

The GateKeeper (THD SpA, Correggio, Italy) is HYEXPAN (polyacrylonitrile), an implantable thin, hydrophilic, self-expanding biocompatible polymer. 34 The device is purported to improve continence by bulking the anal canal through the expansion of the polymer. Patients prepare with two enemas and undergo this procedure under general or local anesthesia. Patients also receive prophylactic antibiotics. Two-millimeter skin incisions are made in six locations circumferentially around the anus 2 cm from the anal verge. Through a dedicated delivery system, the GateKeeper is inserted into the intersphincteric groove to the puborectalis muscle via ultrasound guidance and palpation. Patients are treated with antibiotics for 3 days postoperatively and are advised to bed rest for 2 days. The SphinKeeper (THD SpA) is a modification of the GateKeeper to include 10 insertions of HYEXPAN.

What Data Supports Its Use?

Ratto et al demonstrated the safety and efficacy of the GateKeeper in 14 patients. Four of the prostheses were implanted. In a mean follow-up of 33.5 months, the authors found a significant decrease in incontinence episodes from a mean of 7.1 per week to 1.4 per week. There were also improvements in CCF-FIS and Vaizey scores with improvement in soiling and ability to defer a bowel movement. 34 In follow-up studies, one group found that 30 patients (56%) had a 75% reduction in incontinence episodes at 12 months after implantation and another group found only 48% of patients had at least a 50% reduction in incontinence episodes at 6 months. 35 Ratto et al then evaluated the SphinKeeper for feasibility in 10 patients and found that there were no complications at 3 months of follow-up with one partial dislocation. 36 La Torre et al published preliminary results for the SphinKeeper and found improvement of maximum resting pressure, total number of FI episodes per week, and CCF-FIS. 37

Injectables

What It Is and How It Works?

There have been many products developed to bulk the anus through the injection of materials. The most common materials studied include silicone biomaterial (PTQ), carbon-coated beads (Durasphere), and dextranomer in stabilized hyaluronic acid (NASHA Dx), 38 39 40 although other materials have been considered including autologous fat. 41 All injectables are administered into the surgical anal canal typically in the submucosal space above the dentate line. The PTQ material was injected into the intersphincteric space. Injectables are no longer available in the United States outside of newer clinical trials.

What Data Supports Its Use?

There have been many studies that have found safety with the use of injectables. Most studies found some improvement in short-term continence with injectables including saline. 42 43 44 Maeda et al in a Cochrane review found that NASHA Dx improved continence in 52% of patients in the short term. 45 There is no long-term data that supports the use of injectables for the treatment of FI. Many substances have been tried and have not seemed to work at improving FI.

Secca

What It Is and How It Works?

The Secca system (Curon Medical, Inc., Fremont, CA) is a temperature-controlled radiofrequency device that creates tissue damage allowing for collagen deposition and tightening of the internal anal sphincter. The device is inserted into the anal canal and the radiofrequency energy is delivered through four electrodes. The procedure is typically performed under sedation and local anesthesia with sequential administration of energy to 85°C from just above the dentate line proximally to the top of the surgical anal canal.

What Data Supports Its Use?

Takahashi et al described the safety and efficacy of radiofrequency treatment to the anal canal in 10 patients and found 80% improvement in responders. 46 The authors also found improvement in incontinence and quality of life scores. They found sustained improvement at 2 and 5 years in subsequent study. 47 48 Other groups have found mixed results of short- and long-term success, mostly temporary benefit to no effect, with the Secca procedure. 49 All studies found Secca to be safe with minimal complications. 50 51 Like others in this section, these treatments are not used in the United States due to the success of sacral neuromodulation and sphincter repair.

Treatments No Longer Available for Routine Use

Artificial Bowel Sphincter (Acticon Neosphincter, American Medical Systems)

Artificial urinary sphincters were developed in 1974 for the treatment of urinary incontinence. In 1987, Christiansen and Lorentzen published the first successful use of the artificial urinary sphincter (AMS800 artificial urinary sphincter, American Medical Systems) as an artificial bowel sphincter in a 67-year-old man with myasthenia gravis. 52 They published follow-up work on five patients implanted with artificial urinary sphincter and found improvement in continence for solid and semisolid stool but not diarrhea with manometric studies suggesting that the mechanism of action was the maintenance of an anorectal angle even during defecation. 53

The AMS800 was modified and called the Acticon Neosphincter, and was Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared by humanitarian exemption in 1999 and for all patients in 2001. 54 The device works similarly to the artificial urinary sphincter with a silicone cuff placed around the anal canal, a pressure-regulated balloon placed in the space of Retzius, and a control pump in the labia or scrotum connected with kink-resistant tubing. 54 The cuff is deflated during defecation to allow passage of stool. The treatment was generally reserved for patients with severe FI who have failed other treatments.

O'Brien and Skinner published an early experience with the Acticon Neosphincter in 13 patients and found that most had a successful implant and improvement of incontinence scores. Further, there were two patients who had the device explanted due to infection or erosion. 55 Wong et al published a large, multicenter cohort study of the artificial bowel sphincter implanted in 112 patients and found that there was improvement in continence in the 85% of patients who had a functioning device. The authors found that there were high rates of revision surgery (46%), infection rates requiring revision (25%), and full device explantation (35%). 56 Through the next decade, multiple groups found a similar rates of incontinence improvement in those successfully implanted as well as high rates of revision surgery, infection, and explantation. 57 58 59 60 61 Currently, the Acticon Neosphincter is only FDA approved for humanitarian uses in the United States given the high rate of complications.

Magnetic Sphincter (Fenix, Torax Medical)

Another artificial bowel sphincter that has been developed is the magnetic anal sphincter. This device is a series of titanium beads with magnetic cores that are held together with independent titanium wires to allow for flexibility. The device can also vary in length to accommodate anatomic differences. The device is designed to augment the sphincter complex by resting around the external anal sphincter. The device is placed around 3 to 5 cm from the anal verge around a circumferential tract around the sphincter created through an anterior incision in the perineal body. The device works by reinforcing the existing sphincter complex. Defecation occurs in a normal manner causing the beads to separate from each other.

Lehur et al reported the feasibility of the magnetic anal sphincter in 14 patients and found that the device improved incontinence episodes and quality of life for those with successful implants. 62 There were seven patients who had adverse events including three device explants and two infections. 62 Other groups found similar success with the magnetic sphincter with comparative results with the artificial bowel sphincter and sacral neuromodulation. 63 64 65 66 In April 2017, the manufacturers (Torax and Ethicon) discontinued sales and studies for the device based on the company's business plans. 67

TOPAS Sling (American Medical Systems)

The TOPAS sling was a transobturator placement of a polypropylene mesh tape posterior to the anal canal. The mechanism of action was thought to be due to the sling providing structural support to the anal canal. 68 Mellgren et al published the results of prospective, multicenter study of the TOPAS sling under an investigational device exemption. 68 In 152 women implanted with the TOPAS sling, the authors found that 69.1% of patients achieved success of ≥ 50% reduction in FI episodes with improvement in both incontinence and quality of life scores. The most common adverse events were pelvic pain and infection. 68 Despite the success of the TOPAS sling, the device was removed from the market by the manufacturer due to the medicolegal climate surrounding the use of pelvic mesh.

Colostomy

The last option for treatment of FI is the creation of a colostomy. Norton et al surveyed 63 patients who underwent a colostomy for FI. Eighty-three percent of respondents stated that the colostomy created little to no restriction in their lives with 84% stating that they would have chosen a colostomy again. 69 Colquhoun et al surveyed patients with FI and colostomy to assess quality of life. They found improved social functioning, lifestyle scale, and depression scores. 70 It is important for clinicians to remember that a colostomy may be the best option for some patients to improve lifestyle restrictions experienced due to FI.

Conclusion

There are several options available for the treatment of FI. We have outlined a management algorithm to help guide decision-making and treatment. It is important to align patients to the best treatment based on age, pathophysiology of incontinence, and available expertise to facilitate the best care for this common problem.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Bharucha A E, Fletcher J G, Melton L J, III, Zinsmeister A R. Obstetric trauma, pelvic floor injury and fecal incontinence: a population-based case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(06):902–911. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown H W, Wexner S D, Segall M M, Brezoczky K L, Lukacz E S. Accidental bowel leakage in the mature women's health study: prevalence and predictors. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(11):1101–1108. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andy U U, Vaughan C P, Burgio K L, Alli F M, Goode P S, Markland A D. Shared risk factors for constipation, fecal incontinence, and combined symptoms in older U.S. adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e183–e188. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sultan A H, Kamm M A, Hudson C N, Thomas J M, Bartram C I. Anal-sphincter disruption during vaginal delivery. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(26):1905–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312233292601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willis S, Faridi A, Schelzig S. Childbirth and incontinence: a prospective study on anal sphincter morphology and function before and early after vaginal delivery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2002;387(02):101–107. doi: 10.1007/s00423-002-0296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharucha A E. Fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(06):1672–1685. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaizey C J, Carapeti E, Cahill J A, Kamm M A. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut. 1999;44(01):77–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakx R, Sprangers M A, Oort F J. Development and validation of a colorectal functional outcome questionnaire. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20(02):126–136. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markland A D, Burgio K L, Whitehead W E. Loperamide versus psyllium fiber for treatment of fecal incontinence: the fecal incontinence prescription (Rx) management (FIRM) randomized clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(10):983–993. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goetz L H, Lowry A C. Overlapping sphincteroplasty: is it the standard of care? Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2005;18(01):22–31. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasgow S C, Lowry A C. Long-term outcomes of anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence: a systematic review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(04):482–490. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182468c22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbosa M, Glavind-Kristensen M, Moller Soerensen M, Christensen P. Secondary sphincter repair for anal incontinence following obstetric sphincter injury: functional outcome and quality of life at 18 years of follow-up. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(01):71–79. doi: 10.1111/codi.14792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamblin G, Bouvier P, Damon H. Long-term outcome after overlapping anterior anal sphincter repair for fecal incontinence. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29(11):1377–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paquette I M, Varma M G, Kaiser A M, Steele S R, Rafferty J F. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' clinical practice guideline for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(07):623–636. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richter H E, Matthews C A, Muir T. A vaginal bowel-control system for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(03):540–547. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varma M G, Matthews C A, Muir T. Impact of a novel vaginal bowel control system on bowel function. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(02):127–131. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eclipse. Eclipse system-fecal incontinence. How it works. Accessed July 11, 2019 fromhttp://eclipsesystem.com/about-eclipse

- 18.Eclipse System Instructions For UseAccessed November 6 at:https://eclipsesystem.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/IFU615-Rev-E-Physician-Instructions-for-Use-180912.pdf2019

- 19.Eclipse System Patient BrochureAccessed November 4 at:https://eclipsesystem.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/MKT394-Rev-C-Patient-Brochure.pdf2019

- 20.Richter H E, Dunivan G, Brown H W. A 12-month clinical durability of effectiveness and safety evaluation of a vaginal bowel control system for the nonsurgical treatment of fecal incontinence. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2019;25(02):113–119. doi: 10.1097/SPV.0000000000000681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renew Insert IFU. Accessed November 6, 2019 at:https://renew-medical.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Renew-Inserts-Reader-Spreads_15Aug2018.pdf

- 22.Lukacz E S, Segall M M, Wexner S D. Evaluation of an anal insert device for the conservative management of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(09):892–898. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pickrell K L, Broadbent T R, Masters F W, Metzger J T. Construction of a rectal sphincter and restoration of anal continence by transplanting the gracilis muscle; a report of four cases in children. Ann Surg. 1952;135(06):853–862. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195206000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christiansen J, Sørensen M, Rasmussen OØ. Gracilis muscle transposition for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 1990;77(09):1039–1040. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corman M L, Corman M B. Follow-up evaluation of gracilis muscle transposition for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23(08):552–555. doi: 10.1007/BF02988994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raffensperger J. The gracilis sling for fecal incontinence. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14(06):794–797. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(79)80267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leguit P, Jr, van Baal J G, Brummelkamp W H. Gracilis muscle transposition in the treatment of fecal incontinence. Long-term follow-up and evaluation of anal pressure recordings. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28(01):1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02553893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baeten C, Spaans F, Fluks A. An implanted neuromuscular stimulator for fecal continence following previously implanted gracilis muscle. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31(02):134–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02562646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baeten C GMI, Konsten J, Spaans F.Dynamic graciloplasty for treatment of faecal incontinence Lancet 1991338(8776):1163–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baeten C G, Geerdes B P, Adang E M. Anal dynamic graciloplasty in the treatment of intractable fecal incontinence. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(24):1600–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506153322403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baeten C G, Bailey H R, Bakka A. Safety and efficacy of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence: report of a prospective, multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(06):743–751. doi: 10.1007/BF02238008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wexner S D, Baeten C, Bailey R. Long-term efficacy of dynamic graciloplasty for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(06):809–818. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madoff R D. Surgical treatment options for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(01) 01:S48–S54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ratto C, Parello A, Donisi L. Novel bulking agent for faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2011;98(11):1644–1652. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trenti L, Biondo S, Noguerales F. Outcomes of Gatekeeper™ prosthesis implantation for the treatment of fecal incontinence: a multicenter observational study. Tech Coloproctol. 2017;21(12):963–970. doi: 10.1007/s10151-017-1723-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ratto C, Donisi L, Litta F, Campennì P, Parello A. Implantation of SphinKeeper(TM): a new artificial anal sphincter. Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(01):59–66. doi: 10.1007/s10151-015-1396-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.La Torre M, Lisi G, Milito G, Campanelli M, Clementi I. SphinKeeper™ for faecal incontinence: a preliminary report. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(01):80–85. doi: 10.1111/codi.14801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chan M K, Tjandra J J. Injectable silicone biomaterial (PTQ) to treat fecal incontinence after hemorrhoidectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(04):433–439. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altomare D F, La Torre F, Rinaldi M, Binda G A, Pescatori M. Carbon-coated microbeads anal injection in outpatient treatment of minor fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(04):432–435. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graf W, Mellgren A, Matzel K E, Hull T, Johansson C, Bernstein M.Efficacy of dextranomer in stabilised hyaluronic acid for treatment of faecal incontinence: a randomised, sham-controlled trial Lancet 2011377(9770):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shafik A. Perianal injection of autologous fat for treatment of sphincteric incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38(06):583–587. doi: 10.1007/BF02054115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaizey C J, Kamm M A. Injectable bulking agents for treating faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2005;92(05):521–527. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo C, Samaranayake C B, Plank L D, Bissett I P. Systematic review on the efficacy and safety of injectable bulking agents for passive faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(04):296–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maeda Y, Vaizey C J, Kamm M A. Long-term results of perianal silicone injection for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(04):357–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.01164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maeda Y, Laurberg S, Norton C. Perianal injectable bulking agents as treatment for faecal incontinence in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(02):CD007959. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007959.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takahashi T, Garcia-Osogobio S, Valdovinos M A. Radio-frequency energy delivery to the anal canal for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(07):915–922. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6328-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takahashi T, Garcia-Osogobio S, Valdovinos M A, Belmonte C, Barreto C, Velasco L. Extended two-year results of radio-frequency energy delivery for the treatment of fecal incontinence (the Secca procedure) Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(06):711–715. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi-Monroy T, Morales M, Garcia-Osogobio S. SECCA procedure for the treatment of fecal incontinence: results of five-year follow-up. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(03):355–359. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim D W, Yoon H M, Park J S, Kim Y H, Kang S B. Radiofrequency energy delivery to the anal canal: is it a promising new approach to the treatment of fecal incontinence? Am J Surg. 2009;197(01):14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruiz D, Pinto R A, Hull T L, Efron J E, Wexner S D. Does the radiofrequency procedure for fecal incontinence improve quality of life and incontinence at 1-year follow-up? Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(07):1041–1046. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181defff8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abbas M A, Tam M S, Chun L J. Radiofrequency treatment for fecal incontinence: is it effective long-term? Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55(05):605–610. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182415406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christiansen J, Lorentzen M.Implantation of artificial sphincter for anal incontinence Lancet 19872(8553):244–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Christiansen J, Lorentzen M. Implantation of artificial sphincter for anal incontinence. Report of five cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(05):432–436. doi: 10.1007/BF02563699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gregorcyk S G. The current status of the Acticon Neosphincter. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2005;18(01):32–37. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-864078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Brien P E, Skinner S. Restoring control: the Acticon Neosphincter artificial bowel sphincter in the treatment of anal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43(09):1213–1216. doi: 10.1007/BF02237423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong W D, Congliosi S M, Spencer M P. The safety and efficacy of the artificial bowel sphincter for fecal incontinence: results from a multicenter cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45(09):1139–1153. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6381-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong M T, Meurette G, Wyart V, Glemain P, Lehur P A. The artificial bowel sphincter: a single institution experience over a decade. Ann Surg. 2011;254(06):951–956. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31823ac2bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Melenhorst J, Koch S M, van Gemert W G, Baeten C G. The artificial bowel sphincter for faecal incontinence: a single centre study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(01):107–111. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Brien P E, Dixon J B, Skinner S, Laurie C, Khera A, Fonda D. A prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial of placement of the artificial bowel sphincter (Acticon Neosphincter) for the control of fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(11):1852–1860. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0717-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ruiz Carmona M D, Alós Company R, Roig Vila J V, Solana Bueno A, Pla Martí V. Long-term results of artificial bowel sphincter for the treatment of severe faecal incontinence. Are they what we hoped for? Colorectal Dis. 2009;11(08):831–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Parker S C, Spencer M P, Madoff R D, Jensen L L, Wong W D, Rothenberger D A. Artificial bowel sphincter: long-term experience at a single institution. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46(06):722–729. doi: 10.1097/01.DCR.0000070530.79998.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lehur P A, McNevin S, Buntzen S, Mellgren A F, Laurberg S, Madoff R D. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation for the treatment of fecal incontinence: a preliminary report from a feasibility study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(12):1604–1610. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181f5d5f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong M T, Meurette G, Stangherlin P, Lehur P A. The magnetic anal sphincter versus the artificial bowel sphincter: a comparison of 2 treatments for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54(07):773–779. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3182182689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wong M TC, Meurette G, Wyart V, Lehur P A. Does the magnetic anal sphincter device compare favourably with sacral nerve stimulation in the management of faecal incontinence? Colorectal Dis. 2012;14(06):e323–e329. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.02995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pakravan F, Helmes C. Magnetic anal sphincter augmentation in patients with severe fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58(01):109–114. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sugrue J, Lehur P A, Madoff R D. Long-term experience of magnetic anal sphincter augmentation in patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(01):87–95. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson and Johnson Information Report of the Fenix Continence Restoration SystemAccessed November 8, 2019 at:https://www.jnjmedicaldevices.com/sites/default/files/user_uploaded_assets/pdf_assets/2018-11/099354-180924%20Ethicon_FENIX_Information.pdf

- 68.Mellgren A, Zutshi M, Lucente V R, Culligan P, Fenner D E. A posterior anal sling for fecal incontinence: results of a 152-patient prospective multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(03):3490–3.49E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Norton C, Burch J, Kamm M A. Patients' views of a colostomy for fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48(05):1062–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0868-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colquhoun P, Kaiser R, Jr, Efron J. Is the quality of life better in patients with colostomy than patients with fecal incontinence? World J Surg. 2006;30(10):1925–1928. doi: 10.1007/s00268-006-0531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]