Abstract

Japanese spotted fever, a tick-borne disease caused by Rickettsia japonica, was firstly described in southwestern Japan. There was a suspicion of Rickettsia japonica infected ticks reaching the non-endemic Niigata Prefecture after a confirmed case of Japanese spotted fever in July 2014. Therefore, from 2015 to 2017, 38 sites were surveyed and rickettsial pathogens were investigated in ticks from north to south of Niigata Prefecture including Sado island. A total of 3336 ticks were collected and identified revealing ticks of three genera and ten species: Dermacentor taiwanensis, Haemaphysalis flava, Haemaphysalis hystricis, Haemaphysalis longicornis, Haemaphysalis megaspinosa, Ixodes columnae, Ixodes monospinosus, Ixodes nipponensis, Ixodes ovatus, and Ixodes persulcatus. Investigation of rickettsial DNA showed no ticks infected by R. japonica. However, three species of spotted fever group rickettsiae (SFGR) were found in ticks, R. asiatica, R. helvetica, and R. monacensis, confirming Niigata Prefecture as a new endemic area to SFGR. These results highlight the need for public awareness of the occurrence of this tick-borne disease, which necessitates the establishment of public health initiatives to mitigate its spread.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Infectious diseases, Epidemiology

Introduction

Japanese spotted fever is a tick-borne disease caused by Rickettsia japonica; the disease was first described in Tokushima Prefecture in southwestern Japan and named by Mahara (1989; 1985)1. Clinically, the major complaints are fever after 2 to 8 days of tick bite and rash. In Japan, approximately 250 cases are reported mainly in the western area of Japan, and 16 deaths cases were reported for ten years from 2007 to 20162. With a wide spectrum of host ticks, R. japonica has been detected in eight species of ticks within three genera (Haemaphysalis, Dermacentor and Ixodes)3. Moreover, in recently described cases of Spotted Fever Group Rickettsiae (SFGR), the disease is caused by species other than R. japonica3,4.

The first cases of Japanese spotted fever in the northern part of the coastal area of the Sea of Japan were reported in 2014, in Fukui and Niigata Prefectures4,5. After an epidemiological investigation on the confirmed case of Rickettsia japonica occurred in Niigata Prefecture, the most probable place of contact with ticks was near the patient’s house in an urban area despite no ticks were collected for identification. The last tick survey in Niigata Prefecture occurred in the ’50s6, and it is unknown if there is a change in the endemic ticks’ species in the area. Therefore, there is a concern about the species and the habitat of the ticks harboring R. japonica in Niigata Prefecture which could spread the disease. This study was conducted to detect the tick prevalence and SFGR prevalence by species of ticks in Niigata Prefecture after the occurrence of a Japanese spotted fever human case.

Methods

Area of the study and collection of ticks

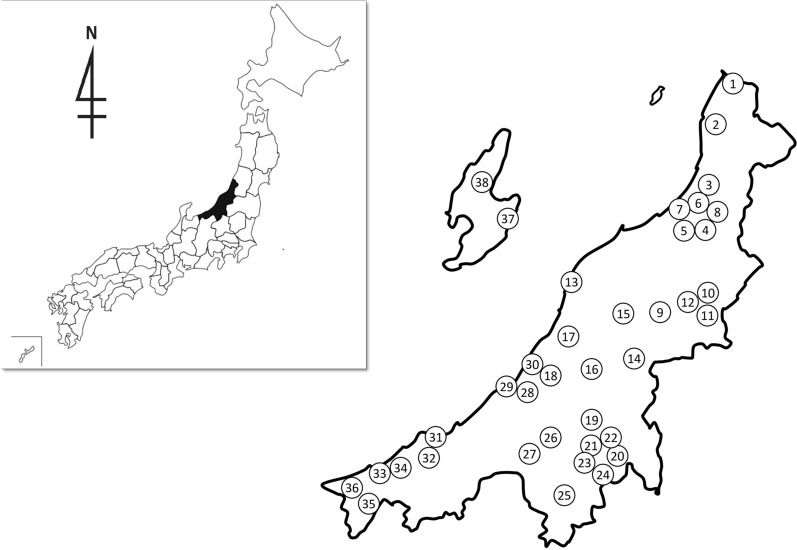

The ticks were collected by flagging method in 38 sites from north to south of Niigata Prefecture including Sado island from June 2015 to November 2017, completing a total of 77 field surveys (Table 1, Fig. 1). Collection sites where humans were likely to be exposed to ticks such as parks, forests with hiking courses, and camping areas were chosen for sampling.

Table 1.

Tick collection sites and elevation in Niigata Prefecture. The Northern (Kaetsu), Central (Chuetsu) and Southern (Joetsu) areas of Niigata Prefecture corresponds to the collection sites 1 to 13, 14 to 30, and 31 to 36, respectively. Sado Island area corresponds to the collection sites 37 and 38.

| No | Site | Elevation (m) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mt. Nihonkoku | 179–300 |

| 2 | Mt. Shinbodake | 560 |

| 3 | Kawabe | 20 |

| 4 | Ohmineyama Park | 80 |

| 5 | Ijimino Park | 20 |

| 6 | Shiratori Park | 190–220 |

| 7 | Sekizawa Forest Park | 130 |

| 8 | Tainaidaira Campground | 130 |

| 9 | Sugikawa Park | 130 |

| 10 | Akasakiyama Forest Park | 330 |

| 11 | Kirinzan Park | 100 |

| 12 | Aganogawa Line Naturel Park | 130 |

| 13 | Mt. Kakuda | 140–250 |

| 14 | Yoshigahira Natural Park | 410 |

| 15 | Gejougawa Dam Park | 40 |

| 16 | Happoudai ikoi-no-mori | 840 |

| 17 | Umamichi Forest Park | 400 |

| 18 | Masugatayama Natural Park | 550 |

| 19 | Tsukioka Park | 420 |

| 20 | Mt. Hakkai | 1200–1300 |

| 21 | Ohsaki Dam Park | 500 |

| 22 | Okura Forest Park | 540 |

| 23 | Sakado Castle Ruins | 280–320 |

| 24 | Ikazawa Campground | 600 |

| 25 | Yuzawa Kogen | 840–950 |

| 26 | Niroku Park | 580 |

| 27 | Bijinbayashi Forest | 310 |

| 28 | Satogaike Sports Field | 20 |

| 29 | Kujiranami | 5 |

| 30 | Akata Castle Ruins | 50 |

| 31 | Tanihama | 230 |

| 32 | Kuwadori Forest park | 360–450 |

| 33 | Takanomine Plateau Forest Park | 230 |

| 34 | Mt. Fudo | 650 |

| 35 | Takanamigaike Campground | 700 |

| 36 | Mt. Myojo | 430 |

| 37 | Sugiike Pond | 720 |

| 38 | Mt. Donden | 700–930 |

Figure 1.

Tick collection sites in Niigata Prefecture. On the left the localization of Niigata Prefecture in Japan. On the right, the numbers indicate the 38 tick collection sites covering the 4 geographical areas of Niigata Prefecture: Northern (Kaetsu), Central (Chuetsu) and Southern (Joetsu) areas of Niigata Prefecture corresponds to the collection sites 1 to 13, 14 to 30, 31 to 36, respectively. Sado Island area corresponds to the collection sites 37 and 38. Maps created using the Geographical Survey Institute Map Vector from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (https://maps.gsi.go.jp/).

Ticks identification

Collected ticks were identified morphologically under stereoscope based on the key by Yamaguti7 and separated by the species, sex and growth stages, collection day and the collection sites. The ticks were separated in micro tubes and stored at − 80 °C until further processing. The identification of ticks with insufficient morphologic characteristics was confirmed by DNA sequencing of the mitochondrial 16S rDNA gene, as previously described8 (data not shown).

DNA extraction

The DNA extraction and purification were done individually for ticks in the adult stage. For ticks in larvae or nymph stages, the DNA was extracted individually or from a pool of 2 to 5 individuals. Ticks were thawed and homogenized using a cell crasher (FastPrep-24, M. P. Biomedicals) in tubes with six steel beads of 3 mm diameter (Metal Bead Lysing Matrix, M. P. Biomedicals). DNA was purified using High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instruction and stored at -80 °C until further processing.

PCR and sequencing analyses

To detect Rickettsia species, nested-PCR for the genus-common 17-kDa antigen gene (17-kDa), citrate synthase gene (gltA), spotted fever group (SFG)-specific outer membrane protein A gene (rOmpA) and outer membrane protein B gene (rOmpB) were targeted. Firstly, the nested PCR targeting 17-kDa protein, and positive samples were tested with another nested PCR targeting gltA; samples that were positive with both PCR assays were concluded as SFGR positive. Additionally, two other nested PCR assays targeting rOmpA and rOmpB were conducted, and the positive samples for four nested PCR were sequenced, and the Rickettsia spp. were identified.

The PCR primers used in this study are summarized in Table 29–13. PCR amplicons were purified using AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter Co., Japan) and sequenced directly using a Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequence Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) and Applied Biosystems 3500 Genetic Analyzer. The analyses of the obtained sequences were carried out using MEGA 5.214. The obtained sequences from this study and from DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases were aligned by Clustal W 2.0. Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree construction and bootstrap analysis (1000 replicates) were performed according to the Kimura 2-parameter distances method.

Table 2.

Primer pairs used for SFGR detection and typing.

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Target gene (amplicon size) | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Rr17k.1p (forward) | TTTACAAAATTCTAAAAACCAT | 17 kDa (450 bp) | 9 |

| Rr17k.539n (reverse) | TCAATTCACAACTTGCCATT | |||

| 2nd | Rr17k.90p (forward) | GCTCTTGCAACTTCTATGTT | ||

| Rr17k.539n (reverse) | TCAATTCACAACTTGCCATT | |||

| 1st | RpCs.780p (forward) | GACCATGAGCAGAATGCTTCT | gltA (382 bp) | 9,10 |

| RpCs.1258n (reverse) | ATTGCAAAAAGTACAGTGAAC | |||

| 2nd | RpCs.877p (forward) | GGGGGCCTGCTCACGGCGG | ||

| RpCs.1258n (reverse) | ATTGCAAAAAGTACAGTGAAC | |||

| 1st | RR 190–70 (forward) | ATGGCGAATATTTCTCCAAAA | rOmpA (540 bp) | 11,12 |

| RR 190–701(reverse) | GTTCCGTTAATGGCAGCATCT | |||

| 2nd | 190-FN1 (forward) | AAGCAATACAACAAGGTC | ||

| 190-RN1 (reverse) | TGACAGTTATTATACCTC | |||

| 1st | rompB OF (forward) | GTAACCGGAAGTAATCGTTTCGTAA | rOmpB (426 bp) | 13 |

| rompB OR (reverse) | GCTTTATAACCAGCTAAACCACC | |||

| 2nd | rompB SFG IF (forward) | GTTTAATACGTGCTGCTAACCAA | ||

| rompB SFG/TG IR (reverse) | GGTTTGGCCCATATACCATAAG | |||

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical permissions were necessary for this study as the parasites were collected from the environment of public places.

Results

Tick species identification

A total of 3336 tick specimens were collected from the 38 sites in Niigata Prefecture (Fig. 1). 3308 ticks were identified to ten species under three genera, while 28 ticks could only be identified as Haemaphysalis spp. (Table 3). The highest frequency was obtained for Haemaphysalis longicornis, collected from 33 of 38 sites, followed by Haemaphysalis flava from 24 sites, and Ixodes ovatus collected from 31 sites. These three species comprised 96.2% of all the collected ticks in this study. Other tick species collected were Ixodes nipponensis collected from 14 sites, Dermacentor taiwanensis from seven sites, Ixodes monospinosus from nine sites, Ixodes persulcatus from five sites, Haemaphysalis megaspinosa from three sites, Ixodes columnae from two sites, and Haemaphysalis hystricis from one site (No. 13).

Table 3.

Prevalence of rickettsial genes detected from ticks by PCR.

| Tick species | No. positive/tested | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Nympha | Larvaa | Total | ||||

| Female | Male | Subtotal | % | ||||

| D. taiwanensis | 0/14 | 0/15 | 0/29 | 0.0 | 0/1 | – | 0/30 |

| H. flava | 0/145 | 2/161 | 2/306 | 0.7 | 9/202 | 1/31 | 12/539 |

| H. hystricis | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0.0 | 0/1 | – | 0/3 | |

| H. longicornis | 0/40 | 0/10 | 0/50 | 0.0 | 6/232 | 3/104 | 9/386 |

| H. megaspinosa | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0.0 | – | – | 0/3 |

| Haemaphysalis spp. | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0.0 | 0/1 | 0/11 | 0/14 |

| I. columnae | – | – | – | – | – | 0/2 | 0/2 |

| I. monospinosus | 3/11 | 1/1 | 4/12 | 33.3 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 4/14 |

| I. nipponensis | 2/4 | 5/12 | 7/16 | 43.8 | 7/10 | 0/2 | 14/28 |

| I. ovatus | 17/177 | 12/167 | 29/344 | 8.4 | 0/2 | – | 29/346 |

| I. persulcatus | 0/2 | 0/5 | 0/7 | 0.0 | 0/1 | – | 0/8 |

| Total | 22/398 | 20/373 | 42/771 | 5.4 | 22/451 | 4/151 | 68/1373 |

aShown by no. pool (2 to 5 ticks/sample).

SFGR prevalence in collected ticks

From 1373 DNA samples of a total of 38 collection sites, 68 samples from 20 sites were positive for SFGR. The tick species presenting SFGR were: H. flava, H. longicornis, I. monospinosus, I. nipponensis, and I. ovatus. Overall, the Rickettsia detection rate for all tested samples adult stage ticks was 5.4%. SFGR positivity by species of ticks were 0.7% in H. flava, 8.4% in I. ovatus, 33.3% in I. monospinosus and 43.8% in I. nipponensis (Table 3). For H. longicornis, the positives samples in SFGR were from nymph and larval stage, but not from adult stage ticks.

SFGR species identification and geographical prevalence

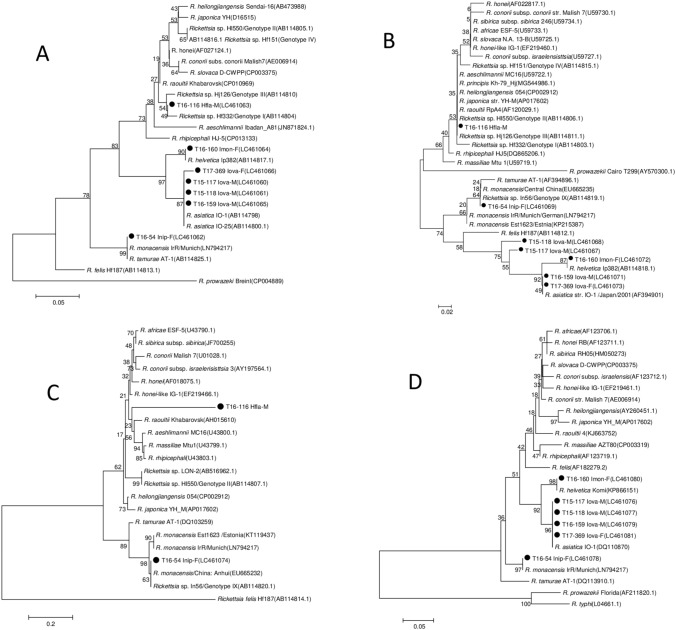

All the 1373 PCR amplicons of SFGR 17-kDa (410 bp) and gltA (342 bp) were sequenced, and none of them presented 100% identity with R. japonica. PCR targeting and sequencing of rOmpA (540 bp) and rOmpB (381 bp) were conducted with the DNA samples of adult ticks, then the Rickettsia spp. were identified using sequence data of 17-kDa, gltA, rOmpA and rOmpB (Fig. 2, Table 4).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis for identification of species of Rickettsiae based on 450 nucleotides of 17 kDa gene (A), 382 nucleotides of gltA gene (B), 540 nucleotides of rOmpA gene (C) and 426 nucleotides of rOmpB gene (D). Sequence were aligned by using MEGA5 software (https://www.megasoftware.net). Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree construction and bootstrap analysis were performed according to the Kimura 2-parameter distances method. Bold-face font indicate positive samples detected from ticks in this study (shown only representative sample no. from among detected SFGR).

Table 4.

Confirmed species/genus of SFGR in this study by sequencing.

| Sample no | Tick | Amplification of gene | Species of Rickettsiae | Sequence of gene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection site | Species | Stage/sex | rOmpA | rOmpB | |||

| T16-159 | No. 9 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | |

| T17-79 | No. 13 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-81 | No. 13 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-82 | No. 13 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-702 | No. 13 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-80 | No. 13 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-418 | No. 16 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-421 | No. 16 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-402 | No. 16 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-411 | No. 16 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-442 | No. 17 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-369 | No. 18 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | |

| T17-371 | No. 18 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-111 | No. 28 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-112 | No. 28 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T15-117 | No. 28 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | |

| T15-118 | No. 28 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | |

| T17-109 | No. 28 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-163 | No. 29 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T17-369 |

| T17-212 | No. 30 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-269 | No. 30 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-259 | No. 30 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-510 | No. 32 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-519 | No. 32 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-507 | No. 32 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-508 | No. 32 | I. ovatus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-477 | No. 37 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-473 | No. 38 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T17-474 | No. 38 | I. ovatus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. asiatica | Same as T16-159 |

| T16-174 | No. 6 | I. monospinosus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. helvetica | Same as T16-160 |

| T16-160 | No. 9 | I. monospinosus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. helvetica | |

| T16-145 | No. 10 | I. monospinosus | Adult/F | No | Yes | R. helvetica | Same as T16-160 |

| T16-146 | No. 10 | I. monospinosus | Adult/M | No | Yes | R. helvetica | Same as T16-160 |

| T16-186 | No. 6 | I. nipponensis | Adult/M | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | Same as T16-54 |

| T16-122 | No. 13 | I. nipponensis | Adult/M | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | Same as T16-54 |

| T16-228 | No. 15 | I. nipponensis | Adult/M | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | Same as T16-54 |

| T17-424 | No. 16 | I. nipponensis | Adult/M | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | Same as T16-54 |

| T16- 54 | No. 28 | I. nipponensis | Adult/F | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | |

| T17-525 | No. 32 | I. nipponensis | Adult/F | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | Same as T16-54 |

| T17-524 | No. 32 | I. nipponensis | Adult/M | Yes | Yes | R. monacensis | Same as T16-54 |

| T16-116 | No. 13 | H. flava | Adult/M | Yes | No | Rickettsia sp. | |

| T16-209 | No. 14 | H. flava | Adult/M | Yes | No | Rickettsia sp. | Same as T16-116 |

A total of 25 out of 29 (89.6%) SFGR positive samples, including sample T16-159 (GenBank accession no. LC461065, LC461071 and LC461079) detected in I. ovatus presented 100% identity with Rickettsia asiatica IO-1 (AB114798, AF394901 and DQ113910) in 17-kDa, gltA and rOmpB sequences. None of the 29 samples amplified rOmpA in PCR. For sample T17-369 (LC461066, LC461073 and LC461081) and T17-163, gltA and rOmpB sequences yielded 100% identity with R. asiatica IO-1 and 99.8% identity for the 17-kDa. For the sample T15-117 (LC4610461060, LC461067 and LC461076) and T15-118 (LC461061, LC461068 and LC461077), 17 kDa and rOmpB amplicons were 100% identical to R. asiatica IO-1 whereas the sequences of gltA presented 99.4% and 98.8% identity for T15-117 and T15-118, respectively.

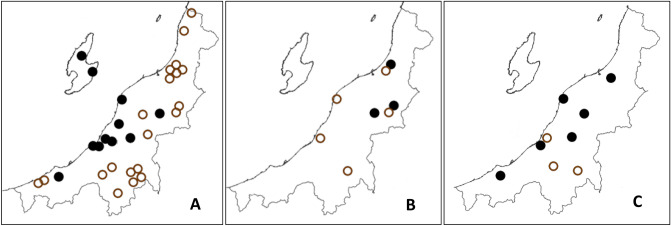

I. ovatus was collected in 31 sites, though R. asiatica was detected from I. ovatus collected in 11 of these sites (Table 5, Fig. 3A). I. ovatus harboring R. asiatica were collected in the central and western part of the prefecture and Sado Island, but not from northeast and mountainous area of the prefectural border with Gunma (collection sites Nos. 20–22, 24–27). Overall, R. asiatica was detected in 8.4% of the I. ovatus adult samples; however, the infection rate varied by collection site such as in Sado Island (site No. 37 and 38 in total) with an infection rate of 50%, Mt. Kakuda (Site No. 13) with 36%, and in Satogaike Sports Field (Site No. 28) with 26%.

Table 5.

Prevalence of rickettsial genes detected from adult ticks by collection sites. The Northern (Kaetsu), Central (Chuetsu) and Southern (Joetsu) areas of Niigata Prefecture corresponds to the collection sites 1 to 13, 14 to 30, and 31 to 36, respectively. Sado Island area corresponds to the collection sites 37 and 38.

| Species of tick | Site no | Total | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | ||

| I. monospinosus | – | – | – | 0/1 | – | 1/2 | – | – | 1/1 | 2/2 | 0/2 | – | 0/2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0/1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0/1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4/12* |

| I. nipponensis | – | – | – | – | – | 1/2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1/1 | – | 1/2 | 1/1 | – | – | – | 0/1 | – | – | – | – | – | 0/1 | – | 1/2 | – | 0/2 | – | 2/4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7/16 |

| I. ovatus | 0/4 | 0/3 | – | 0/9 | 0/5 | 0/11 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 0/2 | 0/7 | – | 5/14 | 0/23 | 0/5 | 4/23 | 1/14 | 2/34 | – | 0/15 | 0/3 | 0/5 | – | 0/2 | 0/11 | 0/32 | 0/1 | 5/19 | 1/6 | 3/28 | – | 4/33 | 0/6 | 0/11 | – | – | 1/4 | 2/2 | 29/344 |

Figure 3.

Niigata prefecture map with the sites where adult stages of Ixodes spp. were collected (Circles), and the occurrence of SFGR (filled circle: SFGR Positive sites, open circle: SFGR Negative sites). From the left, “A” corresponds to I. ovatus and Rickettsia asiatica sites; “B” corresponds to I. monospinosus and R. helvetica sites, and “C” are the I. nipponensis and R. monacensis sites. Maps created using the Geographical Survey Institute Map Vector from the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (https://maps.gsi.go.jp/).

I. monospinosus was present in eight sites. From three sites (site No. 6, 9 and 10) in the northeast region of the prefecture, 4 out of 5 I. monospinosus presented Rickettsia helvetica. In the other five sites with I. monospinosus, R. helvetica was not found (Table 5, Fig. 3B). The four SFGR positive samples including sample T16-160 (LC461064, LC461072 and LC461080) from I. monospinosus adult ticks had 100% identity with Rickettsia helvetica IP382 (AB114817) in 17 kDa, gltA and rOmpB amplicons. None of the four samples amplified rOmpA in PCR.

From seven SFGR positive samples, including sample T16-54 (LC461062, LC461069, LC461074 and LC461078), which were detected in I. nipponensis adult ticks had 100% identity with Rickettsia monacensis IrR Munich (LN794217) in 17 kDa and rOmpB amplicons. The amplicons of 17 kDa showed 100% identity with Rickettsia tamurae AT-1 (AF394896); however, the similarity of the rOmpB amplicons was 97.4% with R. tamurae AT-1 (AF394896). For gltA amplicons, the similarities were 99.7% with R. monacensis IrR Munich (LN794217) and 99.4% with R. tamurae AT-1 (AF394896). For rOmpA amplicons, the similarities were 99.3% with R. monacensis IrR Munich (LN794217) and 95.4% with R. tamurae AT-1 (AF394896). Obtained sequences in this study produced a different cluster from R. tamurae in gltA, rOmpA, and rOmpB regions; therefore, the seven SFGR samples including T16-54 detected in I. nipponensis adult ticks were concluded as R. monacensis. In Ixodes spp., the presence of R. monacensis was high as 43.8% in I. nipponensis, in ticks collected in 6 out of 9 sites (Table 5, Fig. 3C).

Two SFGR samples, including sample T16-116 (LC461063, LC461070, and LC461075), detected in H. flava adult presented the same sequences in 17 kDa, gltA, and rOmpA regions. Both of them did not amplify in rOmpB PCR. The similarity in the 17 kDa region was 99.8% with Rickettsia sp. Hf332 (AB114804) and Rickettsia sp. Hj126 (AB114810), and for gltA, the similarities were 99.7% with Rickettsia sp. Hf332 (AB114804) and 100% with Rickettsia sp. Hj126 (AB114810). For the rOmpA gene, there were no matched sequences in GenBank.

Discussion

The last tick survey in Niigata Prefecture was done in the ’50s6. In this study, we collected D. taiwanensis, H. hystricis, H. megaspinosa, I. columnae, and I. monospinosus species not observed in the previous study, showing the presence of ticks may have been influenced by the environmental change and hosts movement (Sato et al., in preparation). This new ticks/host distribution pattern could bring the pathogen near to humans, facilitating the infection by tick-borne pathogens15. SFGR was detected in ticks collected in 20 of 38 sites from all the collection sites in Niigata Prefecture. In 16 of 19 sites where SFGR positive ticks were not collected, there was a low number of collected ticks (lower than 20), and it might have influenced the SFGR detection rates, as seen in the low prevalence of the SFGR in ticks. To understand the SFGR prevalence in the prefecture, continuous tick collection is needed, especially in sites where the collection number is low. SFGR positivity in adult ticks in Niigata Prefecture was 5.6%, and it is similar to the positivity rate of the neighboring prefecture, Toyama, with 3.3%15. However, when the SFGR detection rate is compared to other prefectures, such as Fukui (22.0%) and six western prefectures including Shizuoka (21.6%)16,17, the SFGR positivity in Niigata Prefecture is still low. In the western part of Japan, SFGR positivity was reported to be as high as 40.5% in H. longicornis17; in contrast, in hokuriku region of Honshu (incl. Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, and Fukui Prefectures), SFGR positivity rates are high in I. monospinosus, with 50% in Toyama15, 43.8% in Fukui16 and 43.8% in Niigata (this study). The tick species prevalence depends on the area/region, therefore the prevalence of the SFGR, and Rickettsia spp. could also vary. Rickettsia spp. have strong host-specificity15–17 and, SFGR detected in this study confirmed this feature. Ticks and Rickettsia sp. were: R. asiatica from I. ovatus, R.helvetica from I. monospinosus, and R. monacensis from I. nipponensis.

The first report of R. asiatica was in Fukushima Prefecture in 1993, described as Rickettsia sp. IO-1 in I. ovatus with subsequent reports in other areas18,19. Moreover, R. asiatica was detected in other tick species, such as H. flava, H. japonica, and H. hystricis 9, showing a diverse ticks host preference. Regarding mammalian hosts, R. asiatica was detected in blood samples of Japanese deer (Cervus nippon); however, the pathogenicity in these hosts is unknown20. SFGR detection in I. ovatus in the neighboring prefecture is varied, with rates of 0.0% in Toyama15, 7.9% in Fukui16, and 8.4% in Niigata (this study). Also, in this case, the positivity rates may vary according to the number of sampling sites and sampling size. It is not clear if the R. asiatica positivity is influenced by the ecology of I. ovatus, environmental factors, or ticks’ susceptibility for pathogens. Continuous research is needed including studies on environmental change and ticks endemicity.

R. helvetica was reported as Japanese spotted fever pathogen in Fukui Prefecture 21, and it is also detected in I. ovatus, I. persulcatus, and H. japonica 19. In this study, R. helvetica was detected only from I. monospinosus, with a positivity rate of 33.3%. In Toyama Prefecture, R. helvetica was detected from 2 of 4 I. monospinosus 15. In this study, R. helvetica positive I. monospinosus was present only in the northeast area of Niigata Prefecture (Site No 6, 9 and 10) (Fig. 3B); however, there was a limited number of I. monospinosus adults (N = 12), present in 8 out of 38 collection sites. To confirm these host specificity and region preferences, further tick collection and field surveys are necessary.

There is only one report of SFGR detected from I. nipponensis in the Toyama prefectural area, reported as Rickettsia sp. In56 9. In this study, seven samples were positives to SFGR in I. nipponensis with 100% identity with Rickettsia sp. In56 (AB114819, AB114820) in gltA and rOmpA regions. Therefore Rickettsia sp. In56 might be R. monacensis. In Europe, R. monacensis is indicated as a spotted fever pathogen22,23 and was also isolated from a spotted fever patient in Korea24. The tick species harboring R. monacensis is Ixodes ricinus in Europe, and in China, the same pathogen was described in I. persulcatus and Ixodes sinensis 25–27. In Korea, similar to this study, R. monacensis was detected from I. nipponensis28. In this study, I. nipponensis presented the highest SFGR positivity in all the collected tick species; SFGR positive I. nipponensis were found from 7 out of 10 sites, indicating R. monacensis might be widely prevalent in Niigata Prefecture.

In Rickettsia sp. Hj126 (AB114803) and Candidatus Rickettsia principis Kh-79_Hj (MG544986), 2 SFGR detected in adult H. flava, the gltA region presented 100% identity and were classified as genotype III by Ishikura’s categorization9 (Fig. 2). The SFGR of the genotype III detected in Japan9, presented the same characteristics of the two SFGR detected in this study, indicating SFGR of the genotype III might be widely prevalent in Japan.

In this study, R. japonica was not detected in the ticks, despite having a case of Japanese spotted fever in 2014, and D. taiwanensis and H. hystricis which are known vectors for R. japonica29 were collected. More wide sampling and/or larger sample size could be necessary to detect a low prevalent species in the arthropod hosts. Additionally, from a clinical point of view, the implementation of serology and DNA isolation might improve the diagnosis and management of patients with spotted fever like illnesses, as recommended in Europe in case of Mediterranean spotted fever like patients30.

Three causative agents of human spotted fever R. asiatica, R. helvetica, and R. monacensis, were detected in this study. The major SFGR positive ticks were Ixodes spp. followed by Haemaphysalis spp. High tick-pathogen specificity was also observed in Ixodes sp. and Rickettsia sp.

Continuous precaution is recommended in activities where there is a potential risk of contact with ticks, and the healthcare system should be aware of spotted fever, particularly since Niigata Prefecture can now be considered an SFGR endemic area and human cases may be occurring.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to alumni of School of Health Sciences, Niigata University; Miyuki Hashimoto, Mika Yokoyama, Hiro Watanabe, Yoichi Abiko, Manaka Oyanagi, Sayaka Ishizuka and Mami Sato of Graduate School of Health Sciences, Niigata University alumni for contribution for tick collection. Thanks to Prof. Ian Kendrich C. Fontanilla of the Institute of Biology, College of Science, University of The Philippines, for kindly reading and improving the manuscript.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: M.S., M.O.S., T.T. Formal analysis: M.S., M.O.S., T.T., K.W. Investigation: R.A., M.K., J.A., A.N., K.W., C.H., S.I. T.T., K.W., M.A.F.R., M.O.S., M.S. Methodology: M.S., M.O.S., K.W. Visualization: R.A., M.O.S., M.S. Writing—original draft: R.A., M.O.S., M.S., T.T. Writing—review & editing: R.A., M.O.S., M.S., T.T. Resources: R.A., M.K., J.A., A.N., K.W., C.H., S.I. T.T., K.W., M.A.F.R., M.O.S., M.S. Supervision: T.T., M.S. Project administration: M.S., T.T. Funding acquisition: M.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K00569.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Reiko Arai, Megumi Sato, and Marcello Otake Sato.

Contributor Information

Reiko Arai, Email: arai.reiko@pref.niigata.lg.jp.

Megumi Sato, Email: satomeg@clg.niigata-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Mahara F, Fujita H, Suto T. 11 cases of Japanese spotted fever and first report of the Tsutsugamushi disease in Tokushima Prefecture. J. Jpn. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1989;63:963–964. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Infectious Diseases Agents surveillance. Report. 2017;38:110–112. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ando S, Fujita H. Diversity between spotted fever group rickettsia and ticks as vector. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2013;64:5–7. doi: 10.7601/mez.64.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takada N, Shimizu T, Igarashi I, Komura K, Hayashi Y, Yano Y, et al. Rapid report of spotted fever diagnosed first in the southern part of Fukui Prefecture, referring to endemic factors and cases around Wakasa Bay. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2015;66:60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arai R, Kato M, Aoki J, Ikeda S, Tamura T, Sato MO, et al. Investigation of rickettsia in ticks collected in the area around Japanese spotted fever patient confirmed first time in Niigata Prefecture. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2017;68:70–74. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saito, Y. Studies on Ixodid ticks part I. On ecology, with reference to distribution and seasonal occurrence of Ixodid Ticks in Niigata Prefecture. Acta Med. Biol. (Niigata)7, 193–209 (1959).

- 7.Yamaguti, N., Tipton, V.J., Keegan Hugh, L., et al. Ticks of Japan, Korea, and the Ryukyu Islands. Brigham Young Univ. Sci. Bull. Biol. Ser. 15, 1 (1971).

- 8.Takano A, Fujita H, Kadosaka T, Takahashi M, Yamauchi T, Ishiguro F, et al. Construction of a DNA database for ticks collected in Japan: Application of molecular identification based on the mitochondrial 16S rDNA gene. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2014;65:13–21. doi: 10.7601/mez.65.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikura M, Ando S, Shinagawa Y, Matsuura K, Hasegawa S, Nakayama T, et al. Phylogenetic analysis of spotted fever group rickettsiae based on gltA, 17-kDa, and rOmpA genes amplified by nested PCR from ticks in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 2003;47:823–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2003.tb03448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regnery RL, Spruill CL, Plikaytis BD. Genotypic identification of rickettsiae and estimation of intraspecies sequence divergence for portions of two rickettsial genes. J. Bacteriol. 1991;173:1576–1589. doi: 10.1128/JB.173.5.1576-1589.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier P-E, Roux V, Raoult D. Phylogenetic analysis of spotted fever group rickettsiae by study of the outer surface protein rOmpA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1998;48:839–849. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-3-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paddock CD, et al. Rickettsia parkeri: A newly recognized cause of spotted fever rickettsiosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004;38:805–811. doi: 10.1086/381894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi Y-J, et al. Spotted fever group and typhus group rickettsioses in humans, South Korea. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005;11:237–244. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.040603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamauchi T, et al. Survey of tick fauna possessing the ability to act as vectors of rickettsiosis in Toyama Prefecture, Japan. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2009;60:23–31. doi: 10.7601/mez.60.23. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishiguro F, et al. Survey of the vectorial competence of ticks in an endemic area of spotted fever group rickettsioses in Fukui Prefecture, Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;52:305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2008.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaowa, et al. Rickettsiae in ticks, Japan, 2007–2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013;19:338–340. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.120856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujita H, Fournier PE, Takada N, Saito T, Raoult D. Rickettsia asiatica sp. nov., isolated in Japan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006;56:2365–2368. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishikura M, Fujita H, Ando S, Matsuura K, Watanabe M. Phylogenetic analysis of spotted fever group rickettsiae isolated from ticks in Japan. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002;46:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2002.tb02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jilintai, et al. Serological and molecular survey of Rickettsial infection in cattle and sika deer in a pastureland in Hidaka District, Hokkaido, Japan. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;61:315–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takada, N., Ishiguro, F., Fujita, H. The first case of spotted fever in Fukui Prefecture, suggesting serologically as R. helvetica infection. IASR. 27, 40–41 (2006).

- 22.Jado I, et al. Rickettsia monacensis and human disease, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13:1405–1407. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.060186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madeddu G, et al. Rickettsia monacensis as cause of Mediterranean spotted fever-like illness, Italy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012;18:702–704. doi: 10.3201/eid1804.111583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim Y-S, et al. First isolation of Rickettsia monacensis from a patient in South Korea. Microbiol. Immunol. 2017;61:258–263. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, et al. Molecular identification of spotted fever group Rickettsiae in ticks collected in central China. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009;15:279–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scarpulla M, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from Central Italy. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:1052–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye X, et al. Vector competence of the tick Ixodes sinensis (Acari: Ixodidae) for Rickettsia monacensis. Parasit. Vectors. 2014;7:512. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0512-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noh Y, et al. Molecular detection of Rickettsia species in ticks collected from the southwestern provinces of the Republic of Korea. Parasit. Vectors. 2017;10:20. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1955-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato K, Takano A, Gaowa AS, Kawabata H. Epidemics of tick-borne infectious disease in Japan. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2019;70:3–14. doi: 10.7601/mez.70.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madeddu G, et al. Mediterranean spotted fever-like illness in Sardinia, Italy: a clinical and microbiological study. Infection. 2016;44:733–738. doi: 10.1007/s15010-016-0921-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.