Abstract

Background

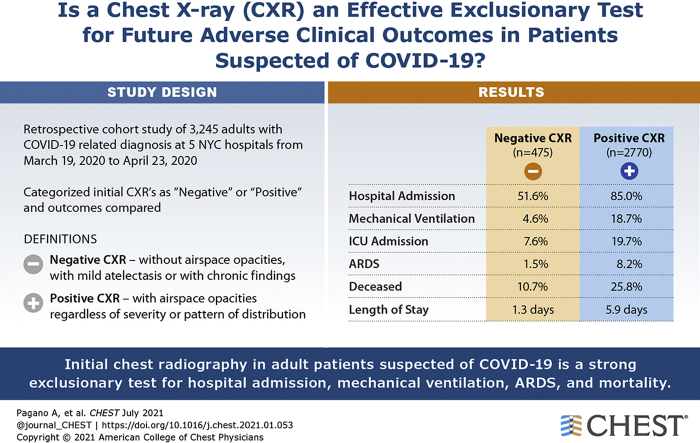

Chest radiography (CXR) often is performed in the acute setting to help understand the extent of respiratory disease in patients with COVID-19, but a clearly defined role for negative chest radiograph results in assessing patients has not been described.

Research Question

Is portable CXR an effective exclusionary test for future adverse clinical outcomes in patients suspected of having COVID-19?

Study Design and Methods

Charts of consecutive patients suspected of having COVID-19 at five EDs in New York City between March 19, 2020, and April 23, 2020, were reviewed. Patients were categorized based on absence of findings on initial CXR. The primary outcomes were hospital admission, mechanical ventilation, ARDS, and mortality.

Results

Three thousand two hundred forty-five adult patients, 474 (14.6%) with negative initial CXR results, were reviewed. Among all patients, negative initial CXR results were associated with a low probability of future adverse clinical outcomes, with negative likelihood ratios of 0.27 (95% CI, 0.23-0.31) for hospital admission, 0.24 (95% CI, 0.16-0.37) for mechanical ventilation, 0.19 (95% CI, 0.09-0.40) for ARDS, and 0.38 (95% CI, 0.29-0.51) for mortality. Among the subset of 955 patients younger than 65 years and with a duration of symptoms of at least 5 days, no patients with negative CXR results died, and the negative likelihood ratios were 0.17 (95% CI, 0.12-0.25) for hospital admission, 0.09 (95% CI, 0.02-0.36) for mechanical ventilation, and 0.09 (95% CI, 0.01-0.64) for ARDS.

Interpretation

Initial CXR in adult patients suspected of having COVID-19 is a strong exclusionary test for hospital admission, mechanical ventilation, ARDS, and mortality. The value of CXR as an exclusionary test for adverse clinical outcomes is highest among young adults, patients with few comorbidities, and those with a prolonged duration of symptoms.

Key Words: ARDS, chest radiography, COVID-19, in-hospital mortality, mechanical ventilation, radiology, respiratory disease, SARS-CoV-2

Abbreviations: CXR, chest radiography; IQR, interquartile range; NLR, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; qSOFA, quick Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment; RT-PCR, reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

FOR EDITORIAL COMMENT, SEE PAGE 21

Since the emergence of COVID-19 and its characterization by the World Health Organization as a pandemic in March 2020,1 management of limited medical resources has become a central challenge in providing life-saving care.2, 3, 4 Given the broad spectrum of the disease, from asymptomatic infections to death,5 rapidly and accurately identifying patients who may not require advanced care may provide opportunities to preserve scarce medical resources. COVID-19 prognosis models largely rely on demographic, medical history, and laboratory data, with imaging input often restricted to chest CT scans.6

Early and continuing limits on the availability and timeliness of real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing, particularly in the United States, has led investigators to explore imaging as a way of augmenting or replacing molecular diagnosis.7, 8, 9 COVID-19 pneumonia can result in a characteristic time-dependent pattern of pulmonary disease on CT scans.10, 11, 12 However, evidence that chest CT scan findings in COVID-19 are nonspecific has led the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Radiology to recommend against the use of chest CT scanning or chest radiography (CXR) alone for the diagnosis of COVID-19 infection.13,14 Regardless of CT scanning’s accuracy as a diagnostic test for COVID-19, it has proven impractical given the potential for cross-infection and the cumbersome cleaning and isolation protocols.15,16 In line with the American College of Radiology recommendations, hospitals largely have avoided CT scanning and CXR for diagnosis and favor portable CXR when assessing COVID-19 severity and investigating alternate or superimposed diagnoses.14

Given the practical advantages of portable CXR and its widespread use on initial presentation, a limited but growing body of literature has sought to explore radiography as a prognostic tool in COVID-19. In one study, a proposed system for grading CXR results severity was found to be an independent predictor of hospital admission and intubation among patients with COVID-19.17 More recent studies also have used CXR to assess COVID-19 severity and predict early intubation, continuous renal replacement therapy, and mortality.18, 19, 20, 21 However, public health organizations like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published research largely have sought to characterize the accuracy of CXR as a diagnostic tool for COVID-19 pneumonia, concluding that it has a low specificity for diagnosis.22

Herein, we aimed to explore the clinical usefulness of CXR as an exclusionary test for adverse clinical outcomes in patients suspected of having COVID-19. We hypothesize that negative CXR results can be used to rule out severe disease progression. We further believe that such a test would be more accurate later in the course of symptoms and in patients with a lower comorbidity burden.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Selection of Participants

In this retrospective cohort study, we examined the hospital course of consecutive adult patients (≥ 21 years of age) with a COVID-19-related encounter diagnosis seeking treatment at five EDs of a multicenter health care system in New York City from March 19, 2020, through April 23, 2020. This study was approved by The Mount Sinai Hospital Institutional Review Board (Identifier: IRB-20-03508). Informed patient consent was waived by the ethics committee for this retrospective study.

Patients with high suspicion of COVID-19 seeking treatment at the ED were identified via our institution’s COVID-19 registry database. All patients underwent a single-view anteroposterior portable CXR examination performed at initial presentation. Patients with multiple CXRs obtained during separate ED encounters were treated separately (n = 78).

Variables

Demographic and clinical variables, including age, sex, race, BMI, comorbidities, RT-PCR results, vital signs, and selected laboratory results, were obtained from an institutional COVID-19 registry. Symptomatology was obtained through chart review by observers blinded to CXR results and based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention description of COVID-19.23 Duration of symptoms was considered important in this study because it reflects length of infection and progression of lung abnormalities on imaging.

Patients were categorized by age using the conventional geriatric cutoff of 65 years. This was thought to be a crucial division for two reasons. First, patients younger than this age tend to have fewer comorbidities.24 Although certain comorbidities were extracted for this analysis, a key limitation of many studies that rely on compiled datasets is a failure to capture the full spectrum and severity of patient comorbidities adequately. Second, at the time of writing this article, a younger US demographic increasingly is showing positive test results for SARS-CoV-2 infection.25 Vital signs were summarized using quick Sequential (Sepsis-Related) Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score.26 Patients were tested variably for COVID-19 infection depending on availability of RT-PCR kits and clinical judgement.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for this study were hospital admission, mechanical ventilation, ARDS, and death for an 85-day follow-up period. Admissions occurring within 14 days of CXR were included and merged with initial ED presentation data; this period allowed admission data from patients who may have been discharged prematurely from the ED while disallowing admission data from patients who may have become infected with COVID-19 after discharge. To ensure the use of data available to point-of-care providers and that results were not associated with infection acquired during hospitalization, only RT-PCR test results obtained within 24 h of admission were considered.

All CXR images were interpreted at the time of acquisition by 40 radiologists across five ED sites. CXR reports were categorized by two independent, blinded observers: those without airspace opacities or having up to mild atelectasis or chronic findings (negative results) and those with airspace opacities regardless of severity or pattern of distribution (positive results) (see e-Table 1 for examples of report language interpretation) (see e-Fig 1 for examples of CXR images). Where categorizations differed, a third observer acted as arbiter. This approach allowed for a focused analysis of radiographic reads as they are available to front-line staff.

Statistical Analysis

The Cohen’s κ coefficient and complete concordance were used to assess agreement in scoring between report interpretations. Complete concordance was defined as the percentage of identical categorizations. Negative predictive values (NPVs) and negative likelihood ratios (NLRs) were calculated for a positive CXR interpretation, thus allowing for assessment for the usefulness of a negative CXR interpretation. Comparison was performed between NPVs and NLRs using a test of differences.27 Bivariate analysis of continuous variables was performed using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, and bivariate analysis of categorical variables was performed using the χ 2 test. To maximize the number of records for multivariate analysis, missing BMI (n = 522 [16.1%]) and qSOFA (n = 11 [0.3%]) results were imputed using predictive mean matching using models that included the outcomes of interest, demographic information, and clinical variables. This was carried out using the mice package.28 Before imputation, data were analyzed to ensure no significant departure from the assumption of missingness at random. Sensitivity analysis was performed by setting missing data to the lowest and highest values and ensuring that no effect in the results related to the primary outcomes of interests and covariates existed. These values then were used in the multivariate model through multiple imputation according to Rubin’s rules.29 Using the lme4 package,30 a mixed-effects logistic regression model adjusted for demographics, comorbidities, qSOFA score at presentation, time of presentation, and the interaction between time of imaging and the categorization of the imaging as fixed effects was performed. The exponentiated coefficient is presented for the interaction variable, which presents the magnitude of the effect of the variable and may be interpreted as the ratio by which the OR changes when the interaction is present. Adjusted ORs are presented for other covariates. We included a random effect for the radiologist finalizing the read because it was found to explain a substantial proportion of variability and improved model fit. A P value of less than .05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. All analyses were completed using R version 3.6.3 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

During the study period, 3,245 adult ED patients suspected of COVID-19 with initial CXR examinations were included (median age, 65 years; interquartile range [IQR], 53-77 years; 1,402 women [43.2%]). Select characteristics and clinical outcomes by CXR results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants in a Study of Initial CXR as an Exclusionary Test for Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Suspected COVID-19

| Characteristic | Overall (N = 3,245) | Negative CXR Results (n = 475) | Positive CXR Results (n = 2,770) | P Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 65.0 (53.0-77.0) | 60.0 (44.0-73.0) | 66.0 (54.0-77.0) | < .001 |

| Age ≥ 65 y | 1,669 (51.4) | 194 (40.8) | 1,475 (53.2) | < .001 |

| Sex (% female) | 1,402 (43.2) | 228 (48.0) | 1,174 (42.4) | .03 |

| Race | < .001 | |||

| White | 756 (23.3) | 132 (27.8) | 624 (22.5) | |

| Asian | 163 (5.0) | 12 (2.5) | 151 (5.5) | |

| Black | 859 (26.5) | 147 (30.9) | 712 (25.7) | |

| Hispanic | 884 (27.2) | 117 (24.6) | 767 (27.7) | |

| Other/unknown | 583 (18.0) | 67 (14.1) | 516 (18.6) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.1 (24.2-32.5) | 27.4 (23.2-31.1) | 28.2 (24.3-32.7) | .002 |

| BMI categories, kg/m2 | .04 | |||

| Normal, < 25 | 825 (30.3) | 123 (36.2) | 702 (29.5) | |

| Overweight, 25-< 30 | 882 (32.4) | 106 (31.2) | 776 (32.6) | |

| Mild to moderate obesity, 30-< 40 | 804 (29.5) | 93 (27.4) | 711 (29.8) | |

| Severe obesity, ≥ 40 | 212 (7.8) | 18 (5.3) | 194 (8.1) | |

| SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results | < .001 | |||

| Negative | 377 (11.6) | 89 (18.7) | 288 (10.4) | |

| Positive | 2,311 (71.2) | 223 (46.9) | 2,088 (75.4) | |

| Unknown | 557 (17.2) | 163 (34.3) | 394 (14.2) | |

| Time period | < .001 | |||

| 3/19/2020-3/25/2020 | 499 (15.4) | 150 (31.6) | 349 (12.6) | |

| 3/26/2020-4/1/2020 | 843 (26.0) | 150 (31.6) | 693 (25.0) | |

| 4/2/2020-4/8/2020 | 852 (26.3) | 59 (12.4) | 793 (28.6) | |

| 4/9/2020-4/15/2020 | 646 (19.9) | 61 (12.8) | 585 (21.1) | |

| 4/16/2020-4/23/2020 | 405 (12.5) | 55 (11.6) | 350 (12.6) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Asthma | 165 (5.1) | 25 (5.3) | 140 (5.1) | .94 |

| COPD | 135 (4.2) | 27 (5.7) | 108 (3.9) | .09 |

| Hypertension | 1,067 (32.9) | 134 (28.2) | 933 (33.7) | .02 |

| Diabetes | 665 (20.5) | 73 (15.4) | 592 (21.4) | .003 |

| Cancer | 181 (5.6) | 29 (6.1) | 152 (5.5) | .66 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 333 (10.3) | 41 (8.6) | 292 (10.5) | .24 |

| Heart failure | 209 (6.4) | 33 (6.9) | 176 (6.4) | .70 |

| Coronary artery disease | 378 (11.6) | 65 (13.7) | 313 (11.3) | .16 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 212 (6.5) | 32 (6.7) | 180 (6.5) | .93 |

| OSA | 52 (1.6) | 5 (1.1) | 47 (1.7) | .40 |

| Liver disease | 51 (1.6) | 10 (2.1) | 41 (1.5) | .42 |

| Chronic viral hepatitis | 23 (0.7) | 2 (0.4) | 21 (0.8) | .61 |

| Smoking status | .33 | |||

| Never | 1,652 (50.9) | 234 (49.3) | 1,418 (51.2) | |

| Former/current | 760 (23.4) | 124 (26.1) | 636 (23.0) | |

| Unknown | 833 (25.7) | 117 (24.6) | 716 (25.8) | |

| Presenting symptoms | ||||

| Fever | 1,956 (60.3) | 249 (52.4) | 1,707 (61.6) | < .001 |

| Chills | 691 (21.3) | 91 (19.2) | 600 (21.7) | .24 |

| Fatigue or malaise | 1,010 (31.1) | 137 (28.8) | 873 (31.5) | .27 |

| Rhinorrhea, sore throat, or congestion | 364 (11.2) | 67 (14.1) | 297 (10.7) | .04 |

| Shortness of breath | 2,166 (66.7) | 250 (52.6) | 1,916 (69.2) | < .001 |

| Cough | 2,139 (65.9) | 304 (64.0) | 1,835 (66.2) | .37 |

| Chest pain or chest tightness | 572 (17.6) | 90 (18.9) | 482 (17.4) | .45 |

| Diarrhea | 554 (17.1) | 74 (15.6) | 480 (17.3) | .38 |

| Nausea or vomiting | 522 (16.1) | 84 (17.7) | 438 (15.8) | .34 |

| Myalgias | 583 (18.0) | 100 (21.1) | 483 (17.4) | .07 |

| Headaches | 299 (9.2) | 49 (10.3) | 250 (9.0) | .42 |

| Loss of taste or smell | 82 (2.5) | 14 (2.9) | 68 (2.5) | .64 |

| Appetite change | 251 (7.7) | 25 (5.3) | 226 (8.2) | .04 |

| Back pain or flank pain | 70 (2.2) | 11 (2.3) | 59 (2.1) | .93 |

| Abdominal pain | 117 (3.6) | 19 (4.0) | 98 (3.5) | .71 |

| Altered mental status | 192 (5.9) | 29 (6.1) | 163 (5.9) | .93 |

| Duration of symptoms, d | 6.0 (3.0,8.0) | 4.0 (2.0,7.0) | 7.0 (3.0,9.0) | < .001 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| Hospital admission | 2,600 (80.1) | 245 (51.6) | 2,355 (85.0) | < .001 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 540 (16.6) | 22 (4.6) | 518 (18.7) | < .001 |

| ICU admission | 582 (17.9) | 36 (7.6) | 546 (19.7) | < .001 |

| ARDS | 235 (7.2) | 7 (1.5) | 228 (8.2) | < .001 |

| Deceased | 765 (23.6) | 51 (10.7) | 714 (25.8) | < .001 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 5.4 (1.7,10.7) | 1.3 (0.2,7.0) | 5.9 (2.4,11.3) | < .001 |

| Vital signs at presentation | ||||

| Body temperature, °C | 37.8 (37.1-38.7) | 37.4 (36.9-38.3) | 37.8 (37.2-38.7) | < .001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 104.0 (92.0-117.0) | 98.0 (87.0-110.0) | 105.0 (94.0-118.0) | < .001 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 21.0 (20.0-28.0) | 20.0 (18.0-20.0) | 22.0 (20.0-28.0) | < .001 |

| Maximum systolic BP, mmHg | 145.0 (131.0-160.0) | 139.0 (125.0-157.0) | 145.0 (132.0-161.0) | < .001 |

| Maximum diastolic BP, mmHg | 84.0 (77.0-93.0) | 84.0 (76.0-92.0) | 84.0 (78.0-93.0) | .18 |

| Minimum systolic BP, mmHg | 110.0 (98.0-122.0) | 115.0 (103.5-130.0) | 108.0 (97.0-120.0) | < .001 |

| Minimum diastolic BP, mmHg | 61.0 (54.0-70.0) | 66.0 (58.0-77.0) | 60.0 (54.0-68.0) | < .001 |

| qSOFA score ≥ 2 | 691 (21.4) | 45 (9.5) | 646 (23.4) | < .001 |

| D-dimer, ng/L | 1.59 (0.89-3.21) | 1.26 (0.53-2.70) | 1.64 (0.91-3.26) | < .001 |

| WBC count, 1,000 cells | 8.20 (5.90-11.50) | 6.83 (5.20-9.93) | 8.40 (6.10-11.60) | < .001 |

Data are presented as No. (%) or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise indicated. CXR = chest radiography; qSOFA = quick sequential (sepsis-related) organ failure assessment; RT-PCR = reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Shows the contrast of each characteristic between negative and positive CXR results.

CXR report categorizations showed excellent agreement between two graders (κ value, 0.96; complete concordance, 99%). With respect to CXR categories, 475 patients(14.6%) showed negative CXR results and 2770 patients showed positive CXR results. Younger median age (60 years vs 66 years; P < .001), female sex (48.0% male vs 42.4% female; P = .03), and lower median BMI (27.4 kg/m2 vs. 28.2 kg/m2; P < .002) were associated with negative CXR results. Lower rates of hypertension (28.2% vs. 33.7%; P = .024) and diabetes (15.4% vs. 21.4%; P = .004) also were associated with negative CXR results. Patients with negative CXR results demonstrated a shorter duration of symptoms (4 days vs 7 days from symptom onset; P < .001) and showed lower rates of fever (52.4% vs. 61.6%; P < .001) and shortness of breath (52.6% vs 69.2%; P < .001) at presentation. The proportion of initial negative CXR results changed with the days of symptom onset (e-Fig 2). This trend is not followed by RT-PCR results (e-Fig 3) and clearly is followed in proportion of deaths (e-Fig 4). Statistically significant differences were seen in presenting vital signs and select laboratory results between patients with negative CXR results and those with positive CXR results; furthermore, a lower positive qSOFA rate (9.5% vs. 23.4%; P < .001) was associated with negative initial CXR results.

A total of 2,600 patients (80.1%) were admitted, 540 patients (16.6%) were intubated, 235 patients (7.2%) demonstrated ARDS, and 764 patients (23.5%) died. Eight patients (0.2%) had not been discharged within a follow-up period of 85 days.

On review of patients with negative CXR results with adverse outcomes, we found that severe comorbidities often were not captured by our extensive list of comorbidities. This increased complexity of the false-negative group is somewhat reflected in comparing the number of comorbidities of deceased patients with negative CXR results with those who survived with negative CXR results (median, 2 [IQR, 0-3] vs 0 [IQR, 0-2]; P = .01); intubation vs no intubation (median, 2 [IQR, 0-3] vs 0 [IQR, 0-2]; P = .01); ARDS vs no ARDS (median, 2 [IQR, 1-3] vs 0 [IQR, 0-2]; P = .05), and admission vs no admission (median, 2 [IQR, 0-3] vs 0 [IQR, 0-1]; P < .001). All comparisons were significant.

Table 2 summarizes accuracy indices for negative CXR results in excluding adverse clinical outcomes. Among all patients, NPVs of negative CXR results for mechanical ventilation and ARDS were 95% (95% CI, 93%-97%; qSOFA, 88%; P < .001) and 99% (95% CI, 97%-99%; qSOFA, 95%; P < .001), respectively, and the NLRs were 0.24 (95% CI, 0.16-0.37; qSOFA, 0.66; P < .001) and 0.19 (95% CI, 0.09-0.40; qSOFA, 0.65; P = .001), respectively. The NPV of negative CXR results for death was 89% (95% CI, 86%-92%) and the NLR was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.29–0.51). The NPV of negative CXR results for hospital admission was 48% (95% CI, 44%-53%; qSOFA, 24%; P < .001) and the NLR was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.23-0.31; qSOFA, 0.78; P < .001).

Table 2.

Accuracy Indices of Negative Initial CXR Results to Exclude Adverse Clinical Outcomes for Patients with Suspected COVID-19

| Variable | NPV | NLR | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 3,245) | ||||

| Hospital admission | 48 (44-53) | 0.27 (0.23-0.31) | 91 (89-92) | 36 (32-39) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 95 (93-97) | 0.24 (0.16-0.37) | 96 (94-97) | 17 (15-18) |

| ARDS | 99 (97-99) | 0.19 (0.09-0.40) | 97 (94-99) | 16 (14-17) |

| Deceased | 89 (86-92) | 0.38 (0.29-0.51) | 93 (91-95) | 17 (16-19) |

| Patients < 65 y (n = 1,576) | ||||

| Hospital admission | 66 (61-72) | 0.22 (0.17-0.27) | 91 (90-93) | 39 (35-44) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 97 (94-99) | 0.19 (0.10-0.36) | 96 (93-98) | 20 (18-22) |

| ARDS | 99 (96-100) | 0.19 (0.07-0.49) | 96 (91-99) | 19 (17-21) |

| Deceased | 97 (95-99) | 0.21 (0.10-0.44) | 96 (92-98) | 19 (17-22) |

| Patients with duration of symptoms ≥ 5 d (n = 1,723) | ||||

| Hospital admission | 56 (49-63) | 0.21 (0.16-0.27) | 94 (92-95) | 30 (26-35) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 96 (92-98) | 0.21 (0.10-0.42) | 97 (95-99) | 13 (11-15) |

| ARDS | 99 (96-100) | 0.11 (0.03-0.45) | 99 (95-100) | 12 (11-14) |

| Deceased | 95 (91-98) | 0.24 (0.13-0.44) | 97 (94-99) | 13 (11-15) |

| Patients < 65 y and symptom duration ≥ 5 d (n = 955) | ||||

| Hospital admission | 71 (62-78) | 0.17 (0.12-0.25) | 94 (92-96) | 32 (27-38) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 98 (95-100) | 0.09 (0.02-0.36) | 99 (95-100) | 16 (13-18) |

| ARDS | 99 (96-100) | 0.09 (0.01-0.64) | 99 (93-100) | 15 (12-17) |

| Deceased | 100 (97-100) | 0.00 (0.00-0.21) | 100 (96-100) | 15 (13-17) |

Data are presented as percentage (95% CI) or ratio (95% CI). COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; CXR = chest radiography; NLR = negative likelihood ratio; NPV = negative predictive value.

A subset analysis of 955 patients younger than 65 years with a duration of symptoms 5 days or more resulted in no deaths among 129 patients(13.5%) with negative initial CXR results. Negative CXR results are a strong negative predictor for mechanical ventilation (NPV, 98% [95% CI, 95%-100%]; NLR, 0.09 [95% CI, 0.02-0.36]), ARDS (NPV, 99% [95% CI, 96%-100%]; NLR, 0.09 [95% CI, 0.01-0.64]), and admission (NPV, 71% [95% CI, 62%-78%]; NLR, 0.17 [95% CI, 0.12-0.25]). When compared with qSOFA, CXR was found to be a significantly superior exclusionary test in terms of NLR and NPV for all outcomes of interest.

In models adjusted for demographic and clinical variables as listed in Table 3, negative CXR results showed a statistically significant negative association with hospital admission (OR, 0.25 [95% CI, 0.18-0.36]; P < .001), mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.33 [95% CI, 0.19-0.56]; P < .001), and mortality (OR, 0.57 [95% CI, 0.37-0.87]; P = .01); a negative association between negative CXR results and ARDS also was noted, but was not significant (OR, 0.15 [95% CI, 0.02-1.04]; P = .06). The interaction between CXR interpretations performed later in the study and negative CXR results was found to be significant for death (exponentiated coefficient, 0.41 [95% CI, 0.18-0.94]; P = .04). Positive RT-PCR results and a qSOFA score of 2 or 3 showed significant associations with hospital admission, mechanical ventilation, ARDS, and mortality. Older age (> 65 years) was associated significantly with mortality (OR, 3.97 [95% CI, 3.19-4.93]; P < .001) and hospital admission (OR, 2.21 [95% CI, 1.73-2.82]; P < .001). Severe obesity was found to be associated with mechanical ventilation, ARDS, and death, but not with hospital admission. Coronary artery disease likewise was associated with death, but not with other outcomes.

Table 3.

Risk of Hospital Admission, Mechanical Ventilation, ARDS, and Death Among Patients With Suspected COVID-19

| Variable | Hospital Admission |

Mechanical Ventilation |

ARDS |

Deceased |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| ≥ 21 and < 65 | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . |

| > 65 | 2.21 (1.73-2.82) | < .001 | 1.23 (0.98-1.54) | .07 | 1.05 (0.77-1.45) | .74 | 3.97 (3.19-4.93) | < .001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . |

| Female | 0.86 (0.68-1.07) | .18 | 0.61 (0.49-0.76) | < .001 | 0.69 (0.51-0.94) | .02 | 0.87 (0.72-1.06) | .17 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . |

| Asian | 0.68 (0.40-1.14) | .14 | 1.03 (0.61-1.73) | .91 | 1.50 (0.75-3.00) | .25 | 0.89 (0.56-1.41) | .6 |

| Black | 0.91 (0.66-1.25) | .57 | 0.90 (0.66-1.21) | .47 | 0.96 (0.62-1.50) | .87 | 0.83 (0.64-1.08) | .17 |

| Hispanic | 0.78 (0.57-1.08) | .13 | 1.10 (0.82-1.48) | .53 | 1.28 (0.84-1.96) | .25 | 0.82 (0.63-1.07) | .15 |

| Other/unknown | 1.17 (0.81-1.68) | .40 | 1.22 (0.89-1.67) | .22 | 1.51 (0.98-2.34) | .06 | 0.98 (0.74-1.31) | .91 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||||||

| Normal, < 25 | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | Reference | ||

| Overweight, 25-< 30 | 1.04 (0.74-1.47) | .82 | 1.31 (0.99-1.74) | .06 | 1.17 (0.79-1.72) | .43 | 1.12 (0.88-1.43) | .37 |

| Mild to moderate obesity, 30-< 40 | 0.94 (0.67-1.33) | .74 | 1.68 (1.26-2.24) | < .001 | 1.47 (0.99-2.19) | .06 | 1.21 (0.94-1.56) | .13 |

| Severe obesity, BMI ≥ 40 | 0.93 (0.49-1.75) | .84 | 3.03 (2.03-4.52) | < .001 | 2.29 (1.34-3.90) | < .001 | 1.61 (1.08-2.41) | .02 |

| SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR results | ||||||||

| Negative | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . |

| Positive | 3.76 (2.76-5.11) | < .001 | 2.60 (1.71-3.95) | < .001 | 5.05(2.19-11.67) | < .001 | 1.83 (1.33-2.53) | < .001 |

| Unknown | 0.30 (0.22-0.43) | < .001 | 0.61 (0.35-1.08) | .09 | 1.49 (0.56-4.01) | .43 | 0.80 (0.51-1.23) | .31 |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . |

| Former/current smoker | 1.06 (0.78-1.42) | .72 | 0.82 (0.63-1.08) | .16 | 1.11 (0.76-1.61) | .58 | 0.89 (0.70-1.13) | .34 |

| Unknown smoking status | 0.69 (0.53-0.90) | .006 | 1.13 (0.88-1.46) | .33 | 1.13 (0.80-1.60) | .49 | 1.24 (0.98-1.56) | .07 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Asthma | 1.16 (0.67-2.00) | .59 | 0.54 (0.31-0.94) | .03 | 0.83 (0.41-1.68) | .6 | 0.62 (0.39-0.99) | .04 |

| COPD | 2.57 (1.21-5.47) | .01 | 1.41 (0.84-2.38) | .19 | 1.43 (0.68-2.98) | .35 | 1.24 (0.80-1.92) | .33 |

| Hypertension | 1.10 (0.82-1.48) | .53 | 0.94 (0.73-1.23) | .69 | 0.67 (0.46-0.97) | .03 | 1.02 (0.81-1.27) | .88 |

| Diabetes | 1.31 (0.92-1.84) | .13 | 1.43 (1.10-1.88) | .01 | 1.31 (0.89. 1.91) | .17 | 1.05 (0.82-1.34) | .7 |

| Cancer | 1.01 (0.59-1.78) | .98 | 0.44 (0.24-0.79) | .01 | 3.76 (2.81-5.04) | < .001 | 1.34 (0.92-1.95) | .13 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.51 (0.93-2.44) | .09 | 0.91 (0.64-1.31) | .62 | 0.85 (0.50-1.45) | .54 | 1.23 (0.90-1.67) | .2 |

| Heart failure | 0.79 (0.44-1.37) | .4 | 0.80 (0.50-1.29) | .36 | 0.74 (0.37-1.49) | .4 | 1.04 (0.71-1.53) | .84 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.34 (0.85-2.09) | .21 | 1.11 (0.79-1.56) | .53 | 1.07 (0.65-1.76) | .79 | 1.60 (1.21-2.13) | < .001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.01 (0.58-1.79) | .91 | 1.18 (0.77-1.80) | .43 | 1.22 (0.67-2.22) | .52 | 1.32 (0.93-1.87) | .12 |

| qSOFA score ≥ 2 | 5.51 (3.62-8.46) | < .001 | 4.08 (3.29-5.07) | < .001 | 3.76 (2.81-5.04) | < .001 | 3.32 (2.72-4.06) | < .001 |

| Time period | ||||||||

| 3/19/2020-4/5/2020 | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . | Reference | . . . |

| 4/6/2020-4/23/2020 | 0.96 (0.74-1.24) | .76 | 0.61 (0.49-0.76) | < .001 | 0.50 (0.36-0.68) | < .001 | 0.84 (0.69-1.03) | .09 |

| Negative CXR results | 0.25 (0.18-0.36) | < .001 | 0.33 (0.19-0.56) | < .001 | 0.15 (0.02-1.04) | .06 | 0.57 (0.37-0.87) | .01 |

| 4/6/2020-4/23/2020 and negative CXR results | 1.28 (0.73-2.27) | .39 | 0.91 (0.31-2.69) | .87 | 1.73 (0.29-10.15) | .54 | 0.41 (0.18-0.94) | .04 |

CXR = chest radiography; qSOFA=quick Sequential [Sepsis-Related] Organ Failure Assessment; RT-PCR = reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction.

Discussion

In our study, we found that CXR is a strong exclusionary test for adverse clinical outcomes. Use of CXR as a prognostic exclusionary test has not been described previously, although its use as a predictive indicator in the COVID-19 pandemic has received increased attention. Our further observation that the predictive power of negative CXR results increases with increased duration of symptoms (at least 5 days) comports with a well-understood time-dependent aspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection that sees a median time from onset of symptoms to hospital admission of 7 days and ARDS in 9 days.31 As expected, negative CXR results are least predictive early in the disease course, when airspace opacities are unlikely, regardless of a patient’s future clinical outcome. In later stages of the disease, negative CXR results carry more predictive weight because sufficient time has allowed for the potential development of airspace opacities.

We found portable CXR to be highly sensitive but nonspecific in the prediction of observed clinical outcomes. These results suggest that although negative CXR results can be exclusionary of adverse outcomes, positive CXR results do not share this same prognostic value. This observation can be explained by the study’s use of a broad interpretation of positive CXR results as consisting of any lung abnormality outside of mild atelectasis or chronic findings and included airspace opacities regardless of severity or pattern of distribution. Studies that characterized the relationship between positive CXR results and poor clinical outcomes have assessed severity of disease more rigorously in positive CXR results either by quantifying lung zone involvement17,21 or by using specific scoring systems that capture disease severity.18, 19, 20 In general, these studies demonstrate that positive CXR results become more specific for adverse outcomes with increased severity of disease.

A prominent example of exclusionary testing that shares similarities with the approach presented here is D-dimer testing in risk assessment for venous thromboembolism. Negative D-dimer test results have 99% to 100% NPV and 0.08 to 0.27 NLR among patients with a low pretest probability for disease.32,33 Even in our study population, which had a very high mortality rate (23.5%) relative to mortality in all confirmed cases in New York State (8%),34 we observed comparably high negative predictive values of negative CXR results for mechanical ventilation (95%) and ARDS (99%). Perhaps more telling are negative likelihood ratios, a statistic not influenced by disease prevalence, for understanding the value of an exclusionary test. NLRs of less than 0.1 result in large and often conclusive changes from before to after test probability.35 In our study, negative CXR results among patients who are younger than 65 years and with a duration of symptoms of at least 5 days, very low NLRs were found for mechanical ventilation (0.09), ARDS (0.09), and death (0).

Our study was guided by the observation that two major factors influence the reliability of CXR as an exclusionary test, the timing of the CXR relative to onset of symptoms, and the patient’s burden of comorbidities. Attempts to subset patients using number of comorbidities were limited by a finite array of comorbidities extracted in our study and by the binary nature of capturing only the presence of disease without fully describing severity. However, age is correlated with the presence and severity of comorbidities, and we found that when combined with duration of symptoms, CXR became a more powerful exclusionary test. A future direction for research would measure a patient’s intrinsic burden of comorbidities better to improve CXR further as an exclusionary test.

Within our study population, 14.6% of patients showed negative initial CXR results, a very low proportion and likely a consequence of regional policies that resulted in only the sickest patients reporting to city EDs during the peak of infections in NYC. Furthermore, our cohort consisted of patients with suspected or presumed COVID-19 infection and not necessarily confirmed diagnoses, that is, those with overt symptomatology in need of prompt care. In less acute settings where patients have either mild symptoms or PCR-confirmed infections that otherwise are asymptomatic, we would expect both the proportion of patients with self-limiting COVID-19 and the proportion of negative initial CXR results to be much higher. In a study conducted from March 9 through March 24, 2020, in patients seeking treatment at urgent care centers in New York City with confirmed COVID-19, 58% of patients showed negative CXR results on presentation.36

On multivariate analysis adjusting for clinical information available to first-line providers, negative CXR results were found to be independent predictors of decreased rates of admission, mechanical ventilation, and death as well as the additional suggestion of a similar association with ARDS that was not statistically significant. Notably, we found that negative CXR interpretations from tests performed later in the crisis were significantly more predictive of decreased death in comparison with earlier interpretations, suggesting acquired expertise by radiologists in detecting COVID-19 pneumonia over the study period. Other possibilities for this trend such as shifts in demographics or disease severity as well as systemic factors related to medical resource allocation were analyzed incompletely in this study.

Interpretation

Because of its retrospective nature, this study had certain intrinsic limitations. First, it is unknown how medical decision-making was affected by limited resources and a desire to control spread of disease within the hospital. RT-PCR testing suffered from moderate sensitivity,37 and early rationing of test kits led to many untested patients either because of clear presence of disease or absence of severe symptoms. For these reasons, all patients with a COVID-19-related encounter and not necessarily a confirmed PCR diagnosis were included in the study; 11.6% showed negative RT-PCR results and 17.2% were not tested. Although this approach maximized the practicality and perhaps translatability of the study, our results possibly are derived from a mixture of unknown additional acute respiratory illnesses. Second, although the analyzed hospital system is the largest in New York City, patients may have sought care outside of our hospitals after first reporting to one of our EDs. Third, a 14-day follow-up period was used to track patients seeking treatment at the ED for possible admission that may have been related to the primary presentation. We could not exclude the possibility of reinfection or the possibility of the patient not being infected at the first encounter and interval infection during the 14-day period. Furthermore, patients were only followed up to discharge, raising the possibility of later related admission or adverse outcome. However, any analysis that would include further readmissions would be confounded by the possibility of secondary causes of an adverse outcome that could not be isolated from the initial primary cause of admission for which the patient was recruited into the study.

CXR is an inexpensive and ubiquitous test already performed on most patients with symptoms of respiratory disease. Our findings suggest that portable CXR can play a role in determining the absence of severe COVID-19. In this regard, we offer the concise view of a portable CXR as being either negative or not negative and suggest clarity from interpreting radiologists in differentiating the two. We believe our conclusions can be expanded outside of the ED to wherever patients suspected of COVID-19 seek treatment. In addition, use of CXR as an exclusionary test may prove useful in future respiratory pandemics where resources are limited or accurate, rapid molecular testing is not yet available. In summary, CXR performed in the ED on patients suspected of having COVID-19 is a strong exclusionary test for adverse clinical outcomes, particularly when limited to patients younger than 65 years and with duration of symptoms of at least 5 days.

Take-home Points.

Study Question: Is chest radiography an effective exclusionary test for future adverse clinical outcomes in patients suspected of COVID-19?

Results: Retrospective cohort study of consecutive patients suspected of SARS-CoV-2 infection at five EDs in New York City. Analysis showed initial chest radiography is a strong exclusionary test for future hospitalization, intubation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and mortality.

Interpretation: Negative initial chest radiography in patients suspected of COVID-19 infection may aid in identifying patients not at risk for adverse clinical outcomes including mortality.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: A. P. had full access to all of the data in the study and affirms that this manuscript is an is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported. A. P., M. F., J. O., S. S., A. J., and J. C. conceived of and designed the study. A. J., Y. S. G., A. B., M. C., C. E., and J. C. supervised the study. A. P., J. C., M. F., J. O., S. S., T. E., S. M., D. T., and M. C. were involved in the acquisition of data. M. F. and J. O. provided the statistical analysis. A. P. and M. F. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. A. P., M. F., J. O., S. S., A. J., Y. S. G., A. B., M. C., C. E., Z. A. F., and J. C. were involved in critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Other contributions: The authors thank Lena Marra for organizing institutional review board approval of this study.

Additional information: The e-Figures and e-Table can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

FUNDING/SUPPORT: The analyses described in this publication were conducted with data or tools supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health [Grant UL1TR001433].

Supplementary Data

Visual Abstract.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. 2020. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020

- 2.Artenstein A.W. In pursuit of PPE. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):e46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mascha E.J., Schober P., Schefold J.C., Stueber F., Luedi M.M. Staffing with disease-based epidemiologic indices may reduce shortage of intensive care unit staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):24–30. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wynants L., Van Calster B., Collins G.S. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19 infection: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2020;369:m1328. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin G.D., Ryerson C.J., Haramati L.B. The role of chest imaging in patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational consensus statement from the Fleischner Society. Chest. 2020;158(1):106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Long C., Xu H., Shen Q. Diagnosis of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): rRT-PCR or CT? Eur J Radiol. 2020;126:108961. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.108961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mei X., Lee H.C., Diao K.Y. Artificial intelligence-enabled rapid diagnosis of patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1224–1228. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0931-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernheim A., Mei X., Huang M. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295(3):200463. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao W., Zhong Z., Xie X., Yu Q., Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214(5):1072–1077. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.22976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ai T., Yang Z., Hou H. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E32–E40. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim clinical guidance for management of patients with confirmed coronavirus disease (COVID-19). 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html

- 14.American College of Radiology ACR recommendations for the use of chest radiography and computed tomography (CT) for suspected COVID-19 infection. 2020. American College of Radiology website. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection

- 15.Mossa-Basha M., Meltzer C.C., Kim D.C., Tuite M.J., Kolli K.P., Tan B.S. Radiology department preparedness for COVID-19: radiology scientific expert review panel. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E106–E112. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanardo M., Martini C., Monti C.B. Management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, in the radiology department. Radiography (Lond) 2020;26(3):264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toussie D., Voutsinas N., Finkelstein M. Clinical and chest radiography features determine patient outcomes in young and middle age adults with COVID-19. Radiology. 2020;297(1):E197–E206. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reeves RA, Pomeranz C, Gomella AA, et al. Performance of a severity score on admission chest radiograph in predicting clinical outcomes in hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [published online ahead of print October 28, 2020]. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 10.2214/AJR.20.24801. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Balbi M., Caroli A., Corsi A. Chest x-ray for predicting mortality and the need for ventilatory support in COVID-19 patients presenting to the emergency department. Eur Radiol. 2020;31(4):1999–2012. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07270-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiao N., Cooper J.G., Godbe J.M. Chest radiograph at admission predicts early intubation among inpatient COVID-19 patients. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(5):2825–2832. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07354-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Smadi A.S., Bhatnagar A., Ali R., Lewis N., Johnson S. Correlation of chest radiography findings with the severity and progression of COVID-19 pneumonia. Clin Imaging. 2020;71:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong H.Y.F., Lam H.Y.S., Fong A.H. Frequency and distribution of chest radiographic findings in patients positive for COVID-19. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E72–E78. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Symptoms of coronavirus. 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html

- 24.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chron Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVIDView: a weekly surveillance summary of U.S. COVID-19 activity. 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/covidview/index.html

- 26.Seymour C.W., Liu V.X., Iwashyna T.J. Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) JAMA. 2016;315(8):762–774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leisenring W., Alonzo T., Pepe M.S. Comparisons of predictive values of binary medical diagnostic tests for paired designs. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buuren Sv, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(3):1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin D.B. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1987. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bates D., Mächler M., Bolker B., Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrier M., Lee A.Y., Bates S.M., Anderson D.R., Wells P.S. Accuracy and usefulness of a clinical prediction rule and D-dimer testing in excluding deep vein thrombosis in cancer patients. Thromb Res. 2008;123(1):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ginsberg J.S., Wells P.S., Kearon C. Sensitivity and specificity of a rapid whole-blood assay for D-dimer in the diagnosis of pulmonary embolism. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(12):1006–1011. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-12-199812150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Johns Hopkins University COVID-19 status report: New York, New York. 2020. Johns Hopkins University website. https://bao.arcgis.com/covid-19/jhu/county/36061.html

- 35.Jaeschke R. Users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 1994;271(9):703–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.9.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinstock M.B., Echenique A., Russell J.W. Chest x-ray findings in 636 ambulatory patients with COVID-19 presenting to an urgent care center: a normal chest x-ray is no guarantee. J Urgent Care Med. 2020;14(7):13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson J., Whiting P.F., Brush J.E. Interpreting a covid-19 test result. BMJ. 2020;369:m1808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.