Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the relationship between urine specific gravity (USG) and the prevalence rate of kidney stone.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of adult participants (≥20 years) of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 2007 to 2008. The USG was divided into three groups: <1.008, 1.008–1.020 and >1.020. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the effect of USG on the prevalence rate of kidney stone.

Results

A total of 4,791 patients were included in this study, of which 464 (9.7%) reported a history of kidney stone. Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, gender, race, hypertension, diabetes, body mass index (BMI), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), USG and urine creatinine were closely related to the prevalence of kidney stones. After adjusting for known confounding factors, multivariate logistic regression showed that the prevalence rate of kidney stone increased with the increase of USG (1.008–1.020 vs. <1.008, OR =1.31, 95% CI, 0.09–1.91, P=0.155; >1.020 vs. <1.008, OR =1.71, 95% CI, 1.16–2.54, P=0.007).

Conclusions

The increase of USG was significantly correlated with self-reported kidney stone. This finding helps to identify risk factors for kidney stones as early as possible in the United States.

Keywords: Kidney stone, urine specific gravity (USG), prevalence, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, cross-sectional survey

Introduction

Kidney stone is a common disease of the urinary system, which refers to the stone that occurs in the renal calyx, renal pelvis and the junction of the renal pelvis and ureter (1). Kidney stones have a high incidence in middle-aged and elderly men (30–60 years) and varies along with gender, age and country (2). Kidney stones are more common in men, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 2:1 (3). The prevalence rate of kidney stones in the United States is 9.6% (4), while in South Korea and China, the prevalence rate of kidney stones is approximately 5.0% and 5.8% (5,6). In the past few decades, the global incidence and prevalence of kidney stones have been increasing (7).

There are a variety of treatment methods for kidney stones, including open lithotomy, laparoscopic lithotomy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, ureteroscopy, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and drug therapy (8). Although various treatment measures have achieved satisfactory results, the recurrence rate of kidney stones is very high (9). Studies have shown that patients with kidney stones tend to relapse within 5 years, and the recurrence rate is approximately 50% (10).

Risk factors for kidney stones include male, age, race, high body mass index (BMI), high blood pressure, diabetes and smoking (11,12). And the increased incidence of the disease is also related to lifestyle, such as increased protein intake, reduced fruit and vegetable intake and insufficient liquid intake (13). Stone type and disease severity can affect the risk of kidney stones recurrence (14). As a reliable indicator of renal concentration and dilution (15), the effect of urine specific gravity (USG) on the prevalence rate of kidney stones is still unknown. The purpose of this study was to determine whether the level of USG was related to the prevalence rate of kidney stones.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE guideline checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-929).

Methods

Study population

The data used in our study came from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database (www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NHANES uses a complex probabilistic sampling design to collect information from different populations through standardized interviews, physical examinations, and sample tests to assess the health and nutritional status of non-institutionalized civilians in the United States. Since 1999, the data have been released every two years for use by researchers.

The USG is only recorded in the NHANES 2007−2008 cycle. There are 5,935 adult participants (≥20 years) in NHANE 2007−2008, of which 5,177 have complete survey data. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) unknown history of kidney stones (n=24); (II) unknown BMI (n=56); (III) unknown blood creatinine (n=291); (IV) unknown or abnormal (>99%) USG (n=15). Finally, the final sample analyzed in this study included 4,791 adult participants.

The present study was complied with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (as revised in 2013). This study used previously collected deidentified data, which was deemed exempt from review by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Zhongda Hospital of Southeast University.

Study variables and outcome

The main predictor of the study is USG, which can be obtained from laboratory data files. USG is the ratio of the density (mass of a unit volume) of urine to the density (mass of the same unit volume) of a reference substance (water). USG was collected in the time of the first morning void. USG is measured by a digital hand-held refractometer ATAGO PAL-10S with automatic temperature compensation. To calculate the USG, place approximately 0.3 mL of well-mixed urine sample on the surface of the prism and press the START key of the refractometer, and the USG value will be displayed on the screen. All final reported data comes from operations within the scope of statistical control determined using the multi-rule quality control system implemented in the Division of Laboratory Sciences, CDC National Center for Environmental Health. USG values vary between 1.000 and 1.040 g/mL, USG less than 1.008 g/mL is regarded as dilute, and USG greater than 1.020 g/mL is considered concentrated (16). Other covariates included gender (male and female), age (20–39, 40–59 and 60+ years), race (Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Mexican American, other Hispanic and other), marital status (married, unmarried and other), education level (less than high school, high school or equivalent, college or above and other), BMI (<25.0, 25.0–29.9 and ≥30.0 kg/m2), blood creatinine, urine albumin, urine creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (<90 and ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2). Hypertension and diabetes are diagnosed based on a doctor's diagnosis. Moreover, the eGFR was calculated by the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (17):

Male: eGFR = 141 × min (Scr/0.9, 1)-0.411 × max (Scr/0.9, 1)-1.209 × 0.993Age × 1.159 (if black)

Female: eGFR = 141 × min (Scr/0.7, 1)-0.329 × max (Scr/0.7, 1)-1.209 × 0.993Age × 1.018 × 1.159 (if black)

The results of interest are the history of kidney stones and the times of kidney stones passed. It can be extracted from questionnaire data files. Participants who answered “Yes” to the question “Have you ever had kidney stones?” were considered to have a history of kidney stones.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed the USG of all participants as classified variables (<1.008; 1.008–1.020; >1.020). Mean ± standard deviation is used to describe the distribution of continuous variables, and proportion is used to calculate the distribution of classified variables. Chi-square analysis was used to evaluate the clinical characteristics of all patients and kidney stones patients. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression model were used to evaluate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the factors associated with kidney stones. We constructed three logical regression models to evaluate the association between USG and kidney stones. In the basic model, due to the correlation between demographic factors and USG, we adjusted the age, gender, race, education and marital status of the participants. Subsequently, taking into account the living conditions of the participants, we further adjusted diabetes, hypertension and BMI in the core model. Finally, in the extended model, we adjust the eGFR. All statistical analyses use R version 3.5.3 (http://www.r-project.org/) and SPSS software (version 24.0). P value ≤0.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant characteristics

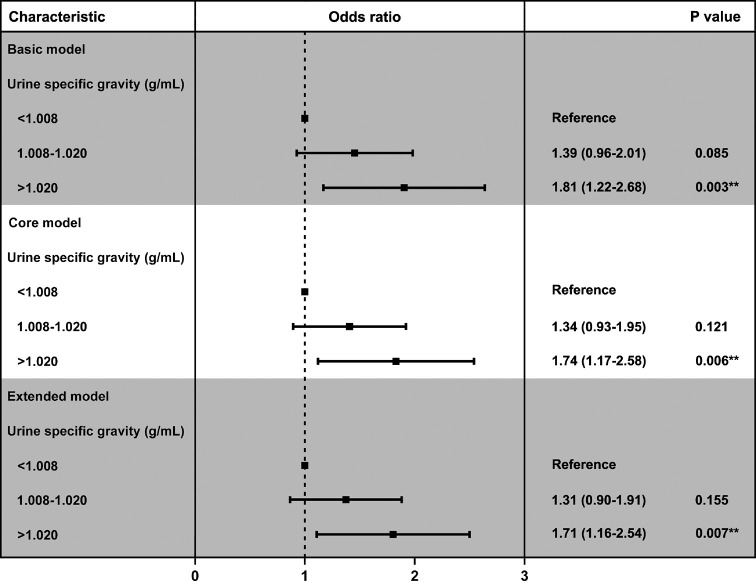

A total of 4,791 eligible participants were enrolled in our cohort through the NHANES 2007–2008 database, of whom 464 (9.7%) answered a history of kidney stones. Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics and chi-square test results of all participants, which are used to compare the differences between the non-stone formers group and stone formers group. We found that USG was higher in patients with stone formation than in those without stone formation (1.018±0.007 vs. 1.017±0.007) (Figure 1). Chi-square test showed significant differences among several variables, including gender (P<0.001), age (P<0.001), race (P<0.001), hypertension (P<0.001), diabetes (P<0.001), BMI (P=0.004), eGFR (P<0.001), USG (P=0.026) and urine creatinine (P=0.041). We found that participants with the history of kidney stones were concentrated in the following factors: male (64.0%), 60+ years (48.5%), non-Hispanic white (60.3%), hypertension-positive (48.1%), diabetes-positive (20.3%), high BMI (≥30.0 kg/m2, 42.4%), low eGFR (<90 mL/min/1.73 m2) and high USG (>1.020, 37.1%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 4791 participants in NHANES 2007−2008.

| Characteristic | Total | None-stone formers | Stone formers | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | ||||

| Total patients | 4,791 | 4,327 (90.3) | 464 (9.7) | |||

| Gender | <0.001 | |||||

| Male | 2,373 (49.5) | 2,076 (48.0) | 297 (64.0) | |||

| Female | 2,418 (50.5) | 2,251 (52.0) | 167 (36.0) | |||

| Age, years | <0.001 | |||||

| 20–39 | 1,550 (32.4) | 1,468 (33.9) | 82 (17.7) | |||

| 40–59 | 1,585 (33.1) | 1,428 (33.0) | 157 (33.8) | |||

| 60+ | 1,656 (34.6) | 1,431 (33.1) | 225 (48.5) | |||

| Race | <0.001 | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2,247 (46.9) | 1,967 (45.5) | 280 (60.3) | |||

| Non-Hispanic black | 951 (19.8) | 889 (20.5) | 62 (13.4) | |||

| Mexican American | 852 (17.8) | 791 (18.3) | 61 (13.1) | |||

| Other Hispanic | 538 (11.2) | 488 (11.3) | 50 (10.8) | |||

| Other | 203 (4.2) | 192 (4.4) | 11 (2.4) | |||

| Marital status | 0.098 | |||||

| Married | 2,586 (54.0) | 2,318 (53.6) | 268 (57.8) | |||

| Unmarried | 1,861 (38.9) | 1,689 (39.0) | 172 (37.1) | |||

| Other | 344 (7.2) | 320 (7.4) | 24 (5.2) | |||

| Education | 0.311 | |||||

| Less than high school | 1,458 (30.4) | 1,309 (30.3) | 149 (32.1) | |||

| High school or equivalent | 1,184 (24.7) | 1,059 (24.4) | 125 (26.9) | |||

| College or above | 2,146 (44.8) | 1,956 (45.2) | 190 (40.9) | |||

| Other | 3 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Hypertension | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 1,679 (35.0) | 1,456 (33.6) | 223 (48.1) | |||

| No/unknown | 3,112 (65.0) | 2,871 (66.4) | 241 (51.9) | |||

| Diabetes | <0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 592 (12.3) | 498 (11.5) | 94 (20.3) | |||

| No/unknown | 4,199 (87.6) | 3,829 (88.5) | 370 (79.7) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.004 | |||||

| Normal (<25.0) | 1,381 (28.8) | 1,275 (29.5) | 106 (22.8) | |||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1,659 (34.6) | 1,497 (34.6) | 162 (34.9) | |||

| Obese (≥30.0) | 1,751 (36.5) | 1,555 (35.9) | 196 (42.2) | |||

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | <0.001 | |||||

| <90 | 1,922 (40.1) | 1,661 (38.4) | 261 (56.3) | |||

| ≥90 | 2,869 (59.9) | 2,666 (61.6) | 203 (43.8) | |||

| Urine specific gravity (g/mL) | 0.026 | |||||

| <1.008 | 506 (10.6) | 471 (10.9) | 35 (7.5) | |||

| 1.008–1.020 | 2,710 (56.6) | 2,453 (56.7) | 257 (55.4) | |||

| >1.020 | 1,575 (32.9) | 1,403 (32.4) | 172 (37.1) | |||

| Urine albumin (μg/mL) | 42.87±277.15 | 42.03±284.88 | 50.67±190.61 | 0.524 | ||

| Urine creatinine (μmg/dL) | 122.33±76.50 | 121.59±76.42 | 129.21±76.94 | 0.041 |

For continuous variables, the t-test for slope was used in generalized linear models. BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 1.

USG values of the stone formers group and none-stone formers groups are shown in violin plots. USG values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. USG, urine specific gravity.

Profiles of USG

Subsequently, we further analyzed the characteristics of the population according to the level of USG (Table 2). We found that people with higher USG were more likely to be male (60.4%), younger (20–39 years, 40.9%), non-Hispanic black (24.1%), diabetes-positive (13.1%), higher BMI (≥30.0 kg/m2, 43.9%), kidney stone positive (10.9%) and higher urine creatinine participants.

Table 2. Characteristics of the study population by categories of urine specific gravity levels in NHANES 2007−2008.

| Characteristic | Urine specific gravity (g/mL) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1.008 | 1.008–1.020 | >1.020 | ||

| Total patients | 506 | 2,710 | 1,575 | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 156 (30.8) | 1,265 (46.7) | 952 (60.4) | |

| Female | 350 (69.2) | 1,445 (53.3) | 623 (39.6) | |

| Age, years | <0.001 | |||

| 20–39 | 132 (26.1) | 774 (28.6) | 644 (40.9) | |

| 40–59 | 183 (36.2) | 852 (31.4) | 550 (34.9) | |

| 60+ | 191 (37.7) | 1,084 (40.0) | 381 (24.2) | |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 315 (62.3) | 1,339 (49.4) | 593 (37.7) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 49 (9.7) | 523 (19.3) | 379 (24.1) | |

| Mexican American | 75 (14.8) | 454 (16.8) | 323 (20.5) | |

| Other Hispanic | 44 (8.7) | 277 (10.2) | 217 (13.8) | |

| Others | 23 (4.5) | 117 (4.3) | 63 (4.0) | |

| Marital status | 0.001 | |||

| Married | 290 (57.3) | 1,477 (54.5) | 819 (52.0) | |

| Unmarried | 186 (36.8) | 1,066 (39.3) | 609 (38.7) | |

| Other | 30 (5.9) | 167 (6.2) | 147 (9.3) | |

| Education | 0.935 | |||

| Less than high school | 153 (30.2) | 816 (30.1) | 489 (31.0) | |

| High school or equivalent | 120 (23.7) | 686 (25.3) | 378 (24.0) | |

| College or above | 233 (46.0) | 1,206 (44.5) | 707 (44.9) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Hypertension | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 174 (34.4) | 1,031 (38.0) | 474 (30.1) | |

| No/unknown | 332 (65.6) | 1,679 (62.0) | 1,101 (69.9) | |

| Diabetes | 0.002 | |||

| Yes | 38 (7.5) | 348 (12.8) | 206 (13.1) | |

| No/unknown | 468 (92.5) | 2,362 (87.2) | 1,369 (86.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.001 | |||

| Normal (<25.0) | 209 (41.3) | 826 (30.5) | 346 (22.0) | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 180 (35.6) | 942 (34.8) | 537 (34.1) | |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 117 (23.1) | 942 (34.8) | 692 (43.9) | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | <0.001 | |||

| <90 | 193 (38.1) | 1,234 (45.5) | 495 (31.4) | |

| ≥90 | 313 (61.9) | 1,476 (54.5) | 1,080 (68.6) | |

| Kidney stone | 0.026 | |||

| Yes | 35 (6.9) | 257 (9.5) | 172 (10.9) | |

| No | 471 (93.1) | 2,453 (90.5) | 1,403 (89.1) | |

| Urine albumin (μg/mL) | 27.63±128.37 | 49.69±305.64 | 48.38±332.35 | 0.048 |

| Urine creatinine (μmg/dL) | 84.45±66.10 | 119.75±62.95 | 158.70±82.24 | <0.001 |

For continuous variables, the t-test for slope was used in generalized linear models. BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Identify risk factors for patients with kidney stones

In order to further identify risk factors associated with the prevalence of kidney stones, we subsequently performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 3). Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, gender, race, hypertension, diabetes, BMI, eGFR and USG were closely related to the prevalence of kidney stones. After adjusting for known confounding factors, multivariate logistic regression showed that the prevalence rate of kidney stone increased with the increase of USG (1.008–1.020 vs. <1.008, OR =1.31, 95% CI, 0.09–1.91, P=0.155; >1.020 vs. <1.008, OR =1.71, 95% CI, 1.16–2.54, P=0.007).

Table 3. Logical regression analysis of factors related to the prevalence rate of kidney stones.

| Characteristic | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysisa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| Female | 0.52 (0.43–0.63) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.45–0.68) | <0.001 | |

| Age, years | |||||

| 20–39 | 1 (reference) | ||||

| 40–59 | 1.97 (1.49–2.60) | <0.001 | 1.65 (1.23–2.22) | 0.001 | |

| 60+ | 2.82 (2.16–3.66) | <0.001 | 1.84 (1.32–2.56) | <0.001 | |

| Race | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 0.49 (0.37–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.47 (0.35–0.64) | <0.001 | |

| Mexican American | 0.54 (0.41–0.72) | <0.001 | 0.63 (0.47–0.86) | 0.003 | |

| Other Hispanic | 0.72 (0.52–0.99) | 0.042 | 0.78 (0.57–1.09) | 0.142 | |

| Other | 0.40 (0.22–0.75) | 0.004 | 0.46 (0.25–0.87) | 0.016 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 1 (reference) | ||||

| Unmarried | 0.88 (0.72–1.08) | 0.217 | |||

| Other | 0.65 (0.42–1.00) | 0.050 | |||

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 1 (reference) | ||||

| High school or equivalent | 1.04 (0.81–1.33) | 0.777 | |||

| College or above | 0.85 (0.68–1.07) | 0.168 | |||

| Hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| No/unknown | 0.55 (0.45–0.67) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.59–0.91) | 0.005 | |

| Diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| No/unknown | 0.51 (0.40–0.65) | <0.001 | 0.68 (0.52–0.88) | 0.004 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| Normal (<25.0) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 1.30 (1.01–1.68) | 0.044 | – | 0.573 | |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 1.52 (1.18–1.94) | 0.001 | – | 0.113 | |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | |||||

| <90 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| ≥90 | 0.49 (0.40–0.59) | <0.001 | 0.76 (0.60–0.97) | 0.029 | |

| Urine specific gravity (g/mL) | |||||

| <1.013 | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | |||

| 1.013–1.020 | 1.41 (0.98–2.03) | 0.066 | 1.31 (0.90–1.91) | 0.155 | |

| >1.020 | 1.65 (1.13–2.41) | 0.009 | 1.71 (1.16–2.54) | 0.007 | |

a, model was adjusted by gender, age, race, hypertension, diabetes, BMI, eGFR and urine specific gravity. BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

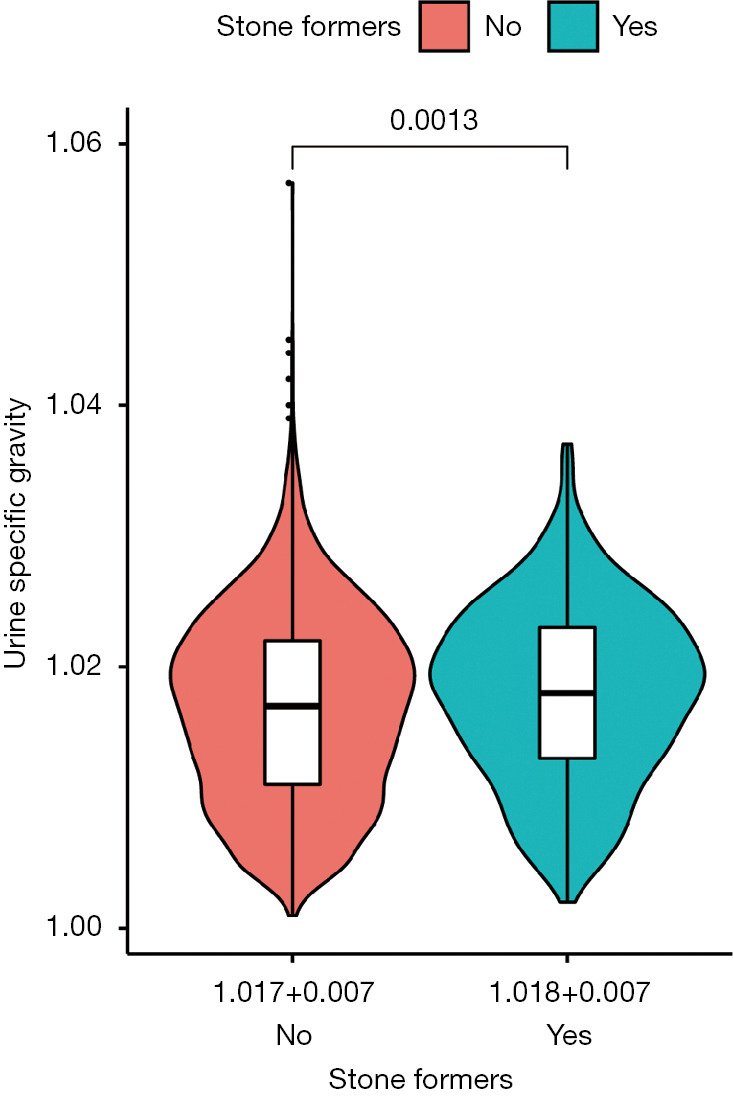

In addition, we constructed three logical regression models to evaluate the association between USG and kidney stones (Figure 2 and Figure S1). The results show that USG has always been a risk factor for kidney stones in the basic model, the core model and the extended model, and the prevalence of kidney stones increases with the increase of USG (Table 4).

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios for associations between the urine specific gravity and the risk of kidney stone in the three groups (<1.008, 1.008–1.020 and >1.020 group).

Table 4. Adjusted odds ratios for associations between the urine specific gravity and the risk of kidney stone in NHANES 2007–2008a.

| Characteristic | N | Basic model | Core model | Extended model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | aOR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Urine specific gravity (g/mL) | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.008 | ||||||

| <1.008 | 506 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| 1.008–1.020 | 2,710 | 1.39 (0.96–2.01) | 0.085 | 1.34 (0.93–1.95) | 0.121 | 1.31 (0.90–1.91) | 0.155 | ||

| >1.020 | 1,575 | 1.81 (1.22–2.68) | 0.003 | 1.74 (1.17–2.58) | 0.006 | 1.71 (1.16–2.54) | 0.007 | ||

a, adjusted covariates: basic model: age, gender, race, education levels, and marital status; Core model: basic model plus diabetes, hypertension, and BMI; Extended model: core model plus estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). CI, confidence interval; aOR, adjusted odds ratio.

Discussion

Kidney stones are usually a recurrent, lifelong disease and recurrent stone attacks have a higher future recurrence rate and worse clinical prognosis (18). Low urine volume, high urinary calcium, high uric aciduria, high oxalic aciduria and abnormal urine pH value can lead to stone formation (19). In addition, due to the complex etiology of stone, large individual, regional differences and high recurrence rates, it is of great significance to in-depth study the risk factors of stone and to find the relevant factors of stone recurrence for guiding treatment and preventing stones.

In this retrospective study, we used the NHANES database that can represent the United States population. Our research showed that there was a significant correlation between USG and self-reported kidney stone disease (P=0.026). The prevalence of kidney stone increased with the increase of USG (1.008–1.020 vs. <1.008, OR =1.31, 95% CI, 0.09–1.91, P=0.155; >1.020 vs. <1.008, OR =1.71, 95% CI, 1.16–2.54, P=0.007) and remained significant after adjusting other confounding factors.

According to statistics, nearly 80% of kidney stones are calcium oxalate stones, 15% are calcium phosphate stones, and the rest are uric acid stones, cystine stones and infectious stones (20). Regardless of the type of stones, the formation of stones requires supersaturated (SS) of urine relative to the stone salt to promote crystal formation and stone growth (21). Studies have shown that high water intake is an impediment factor for kidney stones formation both in vivo and in vitro (22).

There are many indicators (such as fluid volume and hemoglobin) for observing water intake, but due to human factors and individual differences (accuracy of measurement, height, weight status, etc.), the inputs and outputs of the recordings are susceptible. The dynamic change of hemoglobin is restricted by clinical practice. Constraints, we choose the representative and feasible USG as the objective indicator (15).

USG is a simple expression of the amount of soluble components in urine, which refers to the weight ratio of the same volume of urine to the same volume of pure water at 4 °C. Its value varies with the contents of salts and organic compounds in urine. USG mainly depends on the concentration function of the kidney, which is directly proportional to the amount of solute contained in urine and inversely proportional to urine volume (23). Our study found that there was a direct correlation between USG and the prevalence rate of kidney stone, and the result that increase of USG may increase the kidney stone disease risk merits further investigation.

Our research also has some limitations. Firstly, our study is based on the NHANES database, which is a cross-sectional study and requires a prospective study. Secondly, NHANES survey results are based on participants' self-reports data and require the use of a diagnostic test, and there was no information on the time and type of kidney stones. Moreover, the NHANES did not provide the information whether the participants’ urine samples were collected at a specific time (for example, empty in the first morning) or at a random point in time, and the different physical conditions of the participants could affect the USG measurements.

Conclusions

In summary, we observed that the increase of USG was closely related to self-reported kidney stones. Given the degree of association, encouraging people to consume more water may be meaningful for primary and secondary prevention of kidney stones, which is help for to reduce the prevalence rate of kidney stones in the United States.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the invaluable support and useful discussions with other members of the urological department.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81572517 and 81872089), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20161434), Jiangsu Provincial Medical Innovation Team (CXTDA2017025), and Jiangsu Provincial Medical Talent (ZDRCA2016080).

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The present study was complied with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards (as revised in 2013). This study used previously collected deidentified data, which was deemed exempt from review by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Zhongda Hospital of Southeast University. The data in the SEER database does not require informed patient consent.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-929

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-929

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-929). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Sorokin I, Mamoulakis C, Miyazawa K, et al. Epidemiology of stone disease across the world. World J Urol 2017;35:1301-20. 10.1007/s00345-017-2008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shavit L, Ferraro PM, Johri N, et al. Effect of being overweight on urinary metabolic risk factors for kidney stone formation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2015;30:607-13. 10.1093/ndt/gfu350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976-1994. Kidney Int 2003;63:1817-23. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun Y, Zhou Q, Zheng J. Nephrotoxic metals of cadmium, lead, mercury and arsenic and the odds of kidney stones in adults: An exposure-response analysis of NHANES 2007-2016. Environ Int 2019;132:105115. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romero V, Akpinar H, Assimos DG. Kidney stones: a global picture of prevalence, incidence, and associated risk factors. Rev Urol 2010;12:e86-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng G, Mai Z, Xia S, et al. Prevalence of kidney stones in China: an ultrasonography based cross-sectional study. BJU Int 2017;120:109-16. 10.1111/bju.13828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edvardsson VO, Indridason OS, Haraldsson G, et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of kidney stone disease. Kidney Int 2013;83:146-52. 10.1038/ki.2012.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan MS, Pearle MS. Medical management of renal stones. BMJ 2016;352:i52. 10.1136/bmj.i52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zisman AL. Effectiveness of Treatment Modalities on Kidney Stone Recurrence. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1699-708. 10.2215/CJN.11201016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:535-43. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-7-201304020-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong IG, Kang T, Bang JK, et al. Association Between Metabolic Syndrome and the Presence of Kidney Stones in a Screened Population. Am J Kidney Dis 2011;58:383-8. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scales CD, Smith AC, Hanley JM, et al. Prevalence of Kidney Stones in the United States. Eur Urol 2012;62:160-5. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.03.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assadi F, Moghtaderi M. Preventive Kidney Stones: Continue Medical Education. Int J Prev Med 2017;8:67. 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_17_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straub M, Strohmaier WL, Berg W, et al. Diagnosis and metaphylaxis of stone disease - Consensus concept of the National Working Committee on Stone Disease for the Upcoming German Urolithiasis Guideline. World J Urol 2005;23:309-23. 10.1007/s00345-005-0029-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen XT, Wang ZY, Huang Y, et al. Combined detection of urine specific gravity and BK viruria on prediction of BK polyomavirus nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133:33-40. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheuvront SN, Ely BR, Kenefick RW, et al. Biological variation and diagnostic accuracy of dehydration assessment markers. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92:565-73. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009;150:604-12. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parks JH, Coe FL. An increasing number of calcium oxalate stone events worsens treatment outcome. Kidney Int 1994;45:1722-30. 10.1038/ki.1994.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor EN, Mount DB, Forman JP, et al. Association of prevalent hypertension with 24-hour urinary excretion of calcium, citrate, and other factors. Am J Kidney Dis 2006;47:780-9. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leusmann DB, Blaschke R, Schmandt W. Results of 5,035 stone analyses: a contribution to epidemiology of urinary stone disease. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1990;24:205-10. 10.3109/00365599009180859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borghi L, Meschi T, Amato F, et al. Urinary volume, water and recurrences in idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: a 5-year randomized prospective study. J Urol 1996;155:839-43. 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66321-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferraro PM, Taylor EN, Gambaro G, et al. Soda and other beverages and the risk of kidney stones. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:1389-95. 10.2215/CJN.11661112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajadi S, Yu C, Sylvestre JD, et al. Does lower urine-specific gravity predict decline in renal function and hypernatremia in older adults exposed to psychotropic medications? An exploratory analysis. Clin Kidney J 2016;9:268-72. 10.1093/ckj/sfv132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as