Graphical abstract

Keywords: Cavitation bubble, Shock wave, Acoustic focusing, Secondary cavitation, Laser breakdown

Highlights

-

•

Study of cavitation bubble and shock wave dynamics near a concave surface.

Shock wave interaction with the concave reflector and its scattering on a bubble.

-

•

Secondary cavitation induced by the refocused shock wave.

-

•

Visualization by shadow or schlieren photography with adaptive illumination system.

-

•

Theoretical treatment of shock wave propagation with geometrical acoustics.

Abstract

The interplay among the cavitation structures and the shock waves following a nanosecond laser breakdown in water in the vicinity of a concave surface was visualized with high-speed shadowgraphy and schlieren cinematography. Unlike the generation of the main cavitation bubble near a flat or a convex surface, the concave surface refocuses the emitted shock waves and causes secondary cavitation near the acoustic focus which is most pronounced when triggered by the shock wave released during the first main bubble collapse. The shock wave propagation, reflection from the concave surface and its scattering on the dominant cavity is clearly resolvable on the shadowgraphs. The schlieren approach revealed the pressure build up in the last stage of the collapse and the first stage of the rebound. A persistent low-density watermark is left behind the first collapse. The observed effects are important wherever cavities collapse near indented surfaces, such as in cavitation peening, cavitation erosion and ophthalmology.

1. Introduction

This paper reports on the visualization of the intricate dynamics and interplay of the cavitation bubble (CB) and multiple shock waves (SWs) generated in water by a localized, laser-induced breakdown near a concave solid surface. In contrast to the presence of other geometries like plane or convex boundaries that upon reflection do not modify the initially divergent nature of the emitted SWs, the presence of a concave boundary introduces an additional effect with striking consequences: refocusing of an initially divergent SW capable of causing secondary cavitation.

To demonstrate the effects following the laser-generated breakdown in the vicinity of an inward curved boundary [1] we chose a human eye phantom where the acoustic focusing is mediated by the concave surface of a cornea-shaped circular acoustic reflector. To some extent, the experiments thus strive to mimic the transient response of an actual human eye after the application of a laser pulse causing localized ionization on the optical axis within the eye. Even though shock focusing is just one of the observed effects, it is worth being described in detail.

Focusing of SWs can be either intentionally exploited or may be an undesirable effect. Converging shocks are used in technology (SW ignition of fusion [2] and concave detonation-driven shocks [3]) basic science (converging SW triggered star formation, supernova explosions and void collapses [4] and pressure amplification setups [5]) and medicine (extracorporeal SW lithotripsy [6], drug delivery by SW focusing [7], SW mediated cell transfection [8] and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) [9]). Detrimental effects of SW focusing are found in aeronautics (superbooms caused by a turning maneuver of a supersonic aircraft [10]) automotive industry (damage of combustion chambers [11]) and also medicine (possible collateral tissue damage following laser-based ophthalmic procedures [12], [13]).

The present experiments visualize the evolution of the CB and SWs in the first millisecond after the application of a laser pulse typically used in medical procedures in experimental configuration simulating human eye. Due to such a fast dynamics, plethora of CB-SW interactions within this time period could potentially influence the treatment of various pathologies in ophthalmology. In order to assess the invasiveness of such medical treatments and potentially to improve the existing procedure, it is important to understand what is going on in the first millisecond just after the optical breakdown in a geometry confined by SW focusing surfaces.

Water- or tissue-borne, laser-induced shock waves are high-amplitude acoustic pressure pulses that are launched as weak shocks radially away from the optical breakdown where transient localized plasma develops [14], [15], [16]. If the laser pulse is focused within an optically transparent liquid with a large convergence angle, the general form of the emitted shock front can be reasonably well represented by a single radially growing sphere with its center at the location of the optical focus [15], [16]. The initially emitted shock wave (BSW, short for breakdown shock wave) is accompanied by another, slower dynamic relaxation process, by an oscillatory cavitation bubble whose liquid–vapor boundary is first inflated and then deflated until the cavity collapses, ideally emitting another single shock wave (CSW, short for bubble collapse shock wave) during the rebound draining some mechanical energy from the initial bubble [14]. In the second oscillation, the bubble grows to a smaller maximum radius and then implodes, once again releasing the CSW. Ideally, multiple bubble oscillations take place, but practically, due to the reasons of the bubble’s asymmetry, only the first two are most often detected.

During the final stage of the first collapse, the CB retains a spherical symmetry only under idealized conditions, when it was generated by a spherical plasma and if no boundaries and pressure gradients were present in the vicinity of the CB [17], [18], [19], [20]. An elongated plasma source or any pressure gradient in the liquid, even the one caused by the gravity [21] makes the collapse asymmetric. An asymmetrical collapse is in turn accompanied by the emission of multiple CSW, originating from different points in space and time [14], [19]. In comparison with the symmetric collapses, the asymmetric collapses are accompanied by additional phenomena, such as high-velocity liquid jets, annular CB and interplay among multiple SWs and multiple CBs [19].

The main goal of this study is to give a thorough survey of the abundant dynamic effects that follow an optical breakdown in water near a concave surface, supported by simple theoretical models or CB growth and SW propagation. Visual appreciation of these effects is provided by means of appropriate photography and high-speed cinematography. For the sake of encompassing all optically perceivable transient phenomena, our account is bound to remain at a descriptive and qualitative level while, where applicable, drawing quantitative conclusions and comparisons to the existing reports.

The study is thus nonparametric in a sense that laser energy, stand-off distance, acoustic mirror geometry and composition is not varied. We rather focus on various phenomena that are discusses in detail in a review-like fashion and are accompanied with extensive references that can serve as a springboard for those interested to know more about a certain phenomenon occurring in the first millisecond after the breakdown near a concave boundary.

Although the mechanisms and phenomena occurring near non-concave surfaces have already been extensively studied, our visualizations of water response to an optical breakdown near a concave boundary reveal either new features that have not been presented before or known ones that have not been as clearly visualized as shown here in the figures and the accompanying video material. These are: (i) laser-induced SW focusing upon the reflection from a nearby concave solid boundary and consequent formation of secondary acoustic cavitation near the acoustic focus that is most developed when triggered by the first CSW, (ii) acoustic focus migration due to the attraction of the CB by the nearby solid surface, (iii) detailed SW scattering on the growing CB, (iv) SW interaction with a solid reflector and (v) much clearer visualization of the persistent low-density watermark which is left behind the first collapse and the positive pressure pedestal preceding the CSW.

2. Experimental setup

To visualize the SW propagation [22] and CB dynamics, we used a combination of a fast or a still camera with an adaptive pulsed illumination employing either schlieren technique or shadow cinematography [23].

2.1. Environmental conditions

The experiments were performed at 23 °C and unreduced pressure of 97.6 kPa. Saturated vapor pressure at 23 °C is 2.81 kPa [24].

2.2. Materials

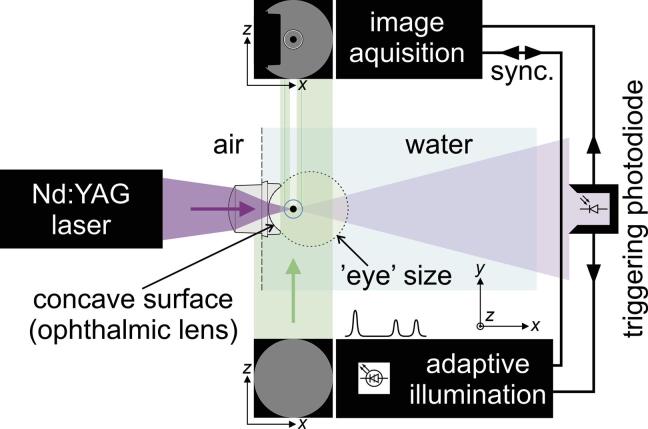

The main constituents used in the central part of the experiment are: water, ophthalmic lens and water tank as illustrated in Fig. 1. The latter are made of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA). The contacting surface of the ophthalmic lens (Capsulotomy lens K30-1120, Katena Products, USA) [25] has a measured curvature of 8.1 mm, different to the 7.8-mm-curvature reported by the lens manufacturer.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of the experimental setup. The central part of the experiment in shown in the top view (the x-y plane including the optical axis), while the excitation beam profile of the illumination pulse and the image on the detector are presented in the side view (the x-z plane). The magenta-colored area represents the path of the excitation pulse, while the green-colored area gives the path of the illumination pulse. The CB (the black disk), the BSW (the blue circle) and the ophthalmic lens deflect the illumination pulse and form the shadow image. For comparison, the approximate dimensions of the human eye in contact with the ophthalmic lens are shown by the yellow colored area. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.3. Excitation and detection

A signal generator was used to trigger the excitation laser with a frequency of 0.2 Hz. Optical breakdown was achieved with a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser similar in performance to typical medical photodisruptors used in ophthalmology. It emits laser pulses at the wavelength of 1064 nm with an energy of 15 mJ.

The photodiode was used to register the transmitted excitation pulse and trigger both, the adaptive illumination system and the image acquisition system.

The collimated 1-inch-diameter background illumination was produced by an adaptable, laser-diode-based illumination system which was developed to simultaneously visualize the dynamics of slow and fast phenomena in optically transparent media [23]. The system can be coupled with still or high-speed cameras and makes it possible to generate an arbitrary train of illumination pulses with a variable pulse duration, pulse energy, and an intrapulse delay with a temporal resolution of 12.5 ns.

Two high-speed visualization techniques were used in the experiments: shadowgraphy and schlieren with the knife-edge set in the vertical position [26], [27], [28]. The shadowgraphy gives sharper wavefronts but poorer contrast when compared to schlieren. The images were calibrated by the insertion of a high precision calibration ruler slides into the water tank.

The shadowgraphy was combined with the still camera (standard 2M pixels industrial camera) and a single illumination pulse with a variable delay between the breakdown and the illumination pulse. Single frames of successive repeatable breakdown events were imaged with time increments of 125 ns yielding a series of multiple-event frames to simulate a single event.

True, single event visualization was performed in the schlieren mode with the synchronization of the fast-camera (Fastcam SA-Z 2100K, Photron, Japan) and the illumination system. The fast-camera was running with a 210 kfps (kilo frames per second) frame rate and the illumination system gave one illumination pulse per frame.

The field of view (FoV) of both cameras is presented in detail in Fig. 2 where two repeatable events were imaged by both methods at the same time after the breakdown. These frames are superimposed on the area of interest behind the ophthalmic lens extracted from Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Field of view (FoV) of two high-speed visualization techniques superimposed on the area of interest behind the ophthalmic lens. Red rectangle: FoV of high-speed camera schlieren technique with a frame rate of 210 kHz, full field pulsed illumination, 61.4-kpx resolution, pixel size of 20 μm and magnification of 0.66. Yellow square: FoV of still camera shadowgraphy, pulsed illumination spot of 24.8-mm diameter, 1.44-Mpx resolution, pixel size of 5.86 μm and magnification of 0.27. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3. Modeling

The experimental shadowgraphs and schlieren images include various well discernible shock fronts and cavitation structures. To better understand the spatiotemporal evolution of these features, we modeled the initial growth of the CB and the propagation, reflection and focusing of the BSW or subsequent CSWs.

3.1. Cavitation bubble growth

For our experimental conditions, the initial growth of the spherical CB is well described by the Rayleigh equation [29]

| (1) |

where r(t) is the radius of the CB wall, is the constant pressure inside the CB which is approximately the saturated vapor pressure, is the constant far-field pressure equal to the unreduced ambient pressure and is the density of water. The overdot is a shorthand notation for the derivative of the variable with respect to time t. The Rayleigh equation assumes an infinite and incompressible liquid with irrotational flow where the contributions due to the surface tension of the CB and due to the dynamic viscosity of water are negligible [30].

The Rayleigh equation is generally solved for the CB collapse where the CB is initial at rest and assumes its maximum radius . Even though explicit closed-form solutions exist for t(r) [31], [32], [33], [34] they have not yet been found for the inverse r(t), but a neat approximation for r(t) was given by Obreschkow et al. [35]

| (2) |

Here is the time normalized to the time of collapse tc, , where

| (3) |

and is the Rayleigh factor. The constant equals and Li is the polylogarithm. The approximation given in Eq. (2) has an error below on the whole interval . As Eq. (2) describes the CB collapse, the substitution transforms it to model the CB growth.

3.2. Shock wave propagation

The propagation model of the spherical BSW assumes an isotropic point source located at the optical breakdown and the propagation is described by a simple ray model that assumes constant acoustic propagation speed in water α1. In reality, the shock wave travels supersonically in the first 100 μm of its path [14], [36]. If needed, this can be remedied by introducing a small time delay to our model, but this delay is small enough that the model fits tightly to the measurements without this correction.

The problem, sketched in Fig. 3(a), is reduced to cylindrical symmetry with the axis of symmetry x extending from the apex of the posterior concave surface of the ophthalmic lens towards the water and the radial axis y. The surface of the ophthalmic lens in contact with water acts as a concave, spherical acoustic mirror. The same object thus acts as a thick positive lens for the laser light and as a spherical mirror for the acoustic waves. This mirror is mathematically described by a spherical cap with the radius R, the base of the cap h and its height g. The breakdown takes place at a distance a.

Fig. 3.

Theoretical estimates of the positions of the BSW fronts (the orange, green, red and blue lines) and the size of the CB (the black disk) are superimposed on the reduced, cylindrical geometry of the lens-water system (a) before SW reflection from the acoustic mirror (4.21 μs after the breakdown; actual spatial dimensions) and (b) after SW reflection (9.46 μs after the breakdown; spatial dimensions normalized to the radius of the concave mirror R). The BSW is emitted at a distance a. An arbitrary ray declined by an angle ϕ < ϕmax is reflected by the acoustic mirror at the point P1 and crosses the axis at the point P2. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The ophthalmic lens (index 2) is made of PMMA and is modelled as a homogeneous and isotropic elastic solid, while water (index 1) is modelled as an inviscid liquid medium. At 23 °C, water has a mass density of ρ1 = 997.5 kg/m3 [37] and acoustic velocity of α1 = 1491 m/s [38]. At the same temperature, PMMA has a mass density of ρ2 = 1183 kg/m3, P-wave velocity of α2 = 2738 m/s and S-wave velocity of β2 = 1387 m/s [39].

To predict the location of the SW front at any time after the breakdown, auxiliary rays (the magenta and brown lines in Fig. 3) are sent from the emission point radially outwards in all directions. At the time t, all the rays have already travelled the same path α1t [the solid magenta and the solid brown lines in Fig. 3]. The endpoints of the neighboring rays [example: the ends of the solid brown lines in Fig. 3(a)] are then connected by lines [example: the dark green short lines in Fig. 3(a)] to recreate the physical SW front. An arbitrary ray [the three brown lines in Fig. 3(a)] with an angle ϕ larger than the angle of the bordering ray that still enters the spherical aperture ϕmax continues its path along the initial direction unobstructed [the dashed brown lines in Fig. 3(a)]. Another ray [the dashed magenta line in Fig. 3(a)] that is directed towards the spherical cap by an angle ϕ < ϕmax is reflected from the acoustic mirror at a point P1 and crosses the axis at a point P2 at a distance b, measured from the apex of the mirror. This distance depends on the angle and forms, due to the acoustic spherical aberration, an extended focal interval [bmin, bmax]. More details about the focal interval can be found in [12]. The length of the ray measured from the origin to the axis is l = l1 + l2. The angle θ denotes the angle of incidence (and the angle of reflection) of the ray on the acoustic mirror.

The portion of the SW front advancing towards the mirror is colored orange and the rest of the SW front missing the mirror is colored green. The converging reflected SW front is colored red and the toroidal one, scattered by the edge of the mirror, is colored blue. The blue dashed line corresponds to the outer rim of the funnel-shaped edge SW. Except for this front head which lies in the constant x plane, all the other fronts dwell in the x-y plane.

The converging SW [the red line in Fig. 3(b)] is reconstructed from the ray endpoints that are calculated using the distances l1 and l2. To further simplify mathematical expressions, all geometrical variables are normalized to the radius of the concave spherical mirror R. The normalized variables are denoted by a superscript tilde (∼). The intersection of an arbitrary ray with the axis takes place at

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

Using these expressions, one derives the points

| (7) |

that are then used to draw the rays reflected from the acoustic mirror.

The SW is also scattered from the mirror’s rim [the blue solid line in Fig. 3(b)] once the initial BSW interacts with it. The cross section of the scattered SW in the x-y plane shows two circular wavefronts, one with the origin at the top edge and one at the bottom one. The two circular wavefronts (the solid blue line) are connected by a vertical line (the dashed blue line) which is a projection of the funnel edge of the SW. Note that this propagation model does not model the SW scattering on the bubble and its transmission into the PMMA lens.

4. Results and discussion

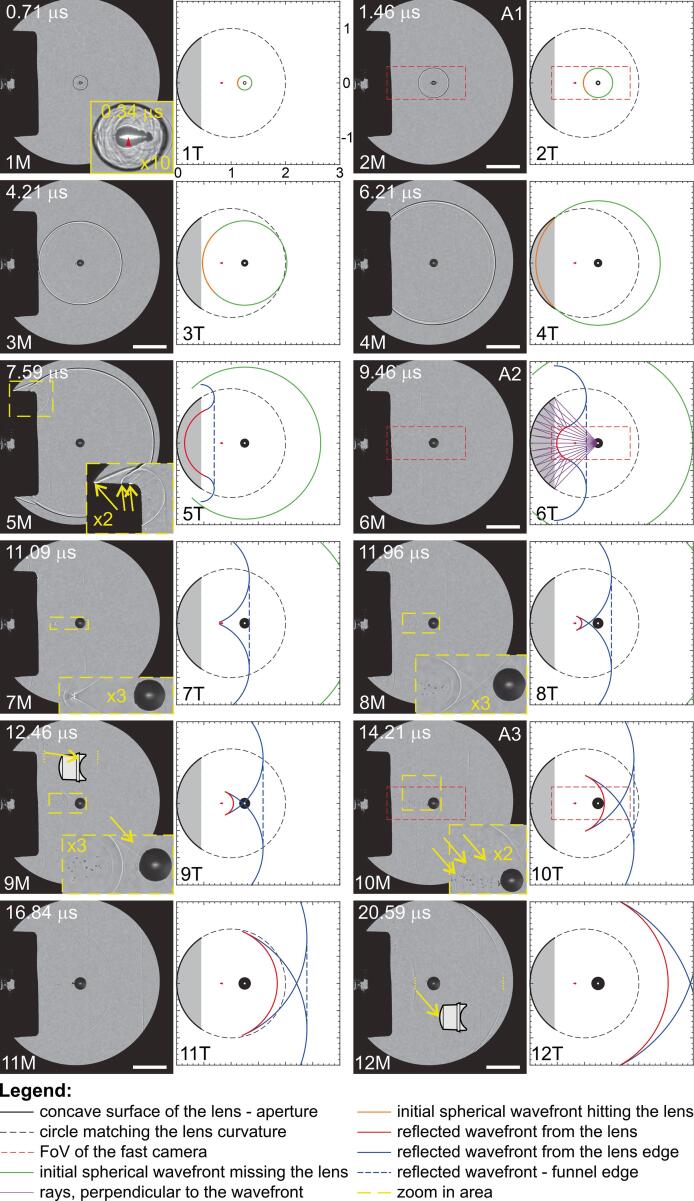

The first 25 μs after the optical breakdown were visualized with still camera shadowgraphy. The representative twelve multiple-event shadowgraphs are presented in Fig. 4. The first frame, which also contains the luminescent plasma, was illuminated 335 ns after the breakdown. The successive frames were obtained with time increments of 125 ns using an appropriate optical filter to get rid of the plasma radiation. Only the selected frames are shown, while the whole animation is available in Video 1. This series of images visually describes the initial propagation of the BSW, its reflection and scattering from the acoustic mirror, its refocusing, secondary acoustic cavitation generation and multiple scattering on the growing CB.

Fig. 4.

Representative multiple-event shadowgraphs 1M-12M revealing the shock wave propagation, reflection, mode-conversion, focusing and scattering, taken soon after the optical breakdown at a breakdown distance a = 10.13 mm (γ = 5.7) from the apex of the concave surface at twelve time instants. Each measurement is accompanied by the shock wave propagation model 1T-12T repeating the main features observed in the measurements. The red dashed rectangles in shadowgraphs (2M, 6M and 10M) are also presented in the schlieren frames (Fig. 5: A1-A3). Yellow arrows guide the eye to interesting features. Vertical yellow dotted lines mark the distance between two selected wavefronts. The dimensions of the model are normalized to the radius of the concave lens surface R = 8.1 mm. Lines: see the legend, black disk: bubble, white dot: breakdown site, red dot with a tail: acoustic focus for paraxial rays (dot) and the focal interval (tail), gray-shaded area: invisible part of the lens. Additionally, frame 6T shows a few rays originating at the breakdown site and being reflected by the lens toward the focal interval. The inset in 1T shows the superposition of the shadowgraph captured at 335 ns after the breakdown and the luminescent 0.4-mm-long plasma. White bar: 5 mm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The continuing dynamics was acquired with a longer time step of 4.762 μs (210 kfps) in the schlieren mode. The selected sixteen frames from a single event are given in Fig. 5, and the whole animation is presented in Video 2. This series of images gives insights into the dynamics of the system which becomes especially rich in light-deflecting structures (SWs and CBs) each time the dominating bubble collapses.

Fig. 5.

Sixteen selected schlieren snapshots A1-D4 of the cavitation and shock wave dynamics extracted from the single event fast camera movie at a breakdown distance a = 10.13 mm (γ = 5.7). Yellow arrows indicate important features on the snapshot. Full white arrowheads designate the x-position of the breakdown, while open white arrowheads indicate the x-position of the center of the dominating cavity, moving towards the ophthalmic lens with time. The vertical dashed white line marks the edge of the ophthalmic lens. The red, green, yellow and blue dots with tails designate the acoustic focus for paraxial rays (dot) and the focal interval (tail) for the BSW, the first, second and third CSW, respectively. The first three frames (A1-A3) are also visualized within the red dashed rectangles (Fig: 4: 2M, 6M and 10M) by the shadowgraphic technique. White bar: 1 mm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The contrast between the two means of visualization can be best seen by comparing Fig. 4 (2M) with Fig. 5 (A1), Fig. 4 (6M) with Fig. 5 (A2) and Fig. 4 (10M) with Fig. 5 (A3).

The discussion of the results will be gathered into separate subsections where each deals with a different phenomenon seen in the measurement of the SW and CB dynamics in the short (the first 25 μs) and long (up to 650 μs) time scale.

4.1. Acoustic focus

To calculate the location of the acoustic focus, the geometry of the acoustic mirror has to be known in advance. The measured curvature of the acoustic mirror is R = 8.10 mm, the base of the cap measures h = 6.77 mm and its height is g = 3.65 mm. The center of the optical breakdown, as measured from the images [Fig. 4 (1M−12M) and Fig. 5 (A1-A4)], was generated at a distance a = (10.13 ± 0.01) mm. Because the theory assumes an isotropic point source, we measured a as the distance between the apex of the acoustic mirror and the center of the emitted BSW. In the inset of Fig. 4 (1M) one can see the BSW (the black ellipse), initial elongated CB (the central black tear-like structure) and the 0.4-mm-long and 60-μm-wide luminescent area corresponding to the maximal extent of the plasma (the white cigar-like saturated image in the center). The red arrowhead indicates the center of the SW [point (a,0)] which coincides with the centroid of the plasma. Note that the plasma starts to grow from the right-hand side and then moves towards the incoming laser pulse [40].

Using Eq. (4) for the outermost rays that still enter the acoustic mirror (ϕ = ϕmax) and for the paraxial rays (ϕ = 0) one obtains the focal interval [bmin, bmax] = [6.51 mm, 6.75 mm]. The paraxial rays cross the optical axis farther from the apex of the mirror. This point is marked by the red dot in Fig. 4 (T1-T12) and Fig. 5, and the whole interval is depicted by the red tail extending from the red dot towards the apex. Assuming the constant acoustic velocity α1 = 1491 m/s of the BSW, the BSW is expected to arrive to the focal interval at 11.16 μs. Fig. 4 (7M, 7T at 11.09 μs) shows the reflected BSW reaching the focal interval at the predicted time, having the predicted shape of the wavefront.

The first collapse of the main CB launches the CSW from the small volume located slightly closer to the apex at aC1 < a than the BSW [Fig. 5 (B2)]. As measured from Fig. 5 (B2), aC1 = (9.78 ± 0.01) mm. Since the source moves towards the acoustic mirror, the new focal interval [6.73 mm, 6.91 mm] [the green dot with a tail in Fig. 5 (B2-D4)] moves away from the mirror.

The second collapse of the main cavity launches another CSW [Fig. 5 (C4)]. It is emitted at a distance aC2 = 9.07 mm < aC1 and refocuses in the interval [7.24 mm, 7.32 mm] [the yellow dot with a tail in Fig. 5 (C4-D4)].

The third collapse of the dominating cavity takes place at aC3 = 8.49 mm < aC2 [Fig. 5 (D4)]. The emitted CSW refocuses in the interval [7.73 mm, 7.74 mm] [the blue dot in Fig. 5 (D4)].

Since the emission point of the BSW and the consequent CSWs is larger than R, the SWs refocus between the acoustic mirror and the point of the SW emission. As the SW source moves towards R from the right, the focal interval is approaching R from the left. The closer is the SW emission point to the center of the curvature R, the narrower is the focal interval. This means that the acoustic spherical aberration is less pronounced the closer is the SW origin to the center of curvature.

4.2. Basic bubble dynamics

Based on the acquisition times of the schlieren images captured before and after the initial CB collapse Fig. 5 (B1, B2), the first collapse is estimated to occur 327 μs after the breakdown. This gives the measured collapse time (one half of the time of the first CB oscillation) of 164 μs. The maximum radius of the bubble extracted from Fig. 5 (A4) is 1.79 mm. If the Rayleigh expression for the collapse time is calculated employing Eq. (3) and using the measured maximum CB radius, one obtains a slightly longer collapse time of 168 μs. Moreover, for a CB collapsing near a rigid, but flat boundary at a normalized standoff distance γ = a/r0 = 5.7 (γ has the same value in Figs. 4 and 5), the collapse time is prolonged [41] by a factor of (1 + 0.203/γ) = 1.036 yielding the expected collapse time of 174 μs. A similar prolongation factor was derived by Tomita et al. [1] for a collapse near a concave surface, but only if the radius of curvature of the acoustic mirror at its apex is larger than 4a/3, which is again larger than the value 0.80a pertaining to our experiments.

This leads to a conclusion that a concave solid surface affects the collapse time differently than the flat surface and that the surface curvature is thus important in estimating the CB oscillation time. On the one hand, the concave surface affects the fluid flow caused by the oscillatory motion of the CB differently than the flat surface [42] but what is often neglected, the boundary also reflects the BSW back towards the CB. The reflected BSW interacts with the CB, in many circumstances forcing it to a faster collapse [43]. The extent to which the SW disturbs the cavities depends on the duration and amplitude of the positive and negative phase of the SW, bubble size and its phase within the oscillation period [44], [45].

Another important consequence the rigid surface has on the cavity is that it attracts the CB towards the boundary bringing additional asymmetry into bubble dynamics. Extensive literature is available describing this effect when the boundary is flat [1], [20], [46], [47] or convex [1], [48] but very scarce when the boundary is concave [1], [49], [50]. To visually follow the translation of the dominating cavity, the frames in Fig. 5 are equipped with the white arrowheads that designate the fixed x-position of the breakdown (full arrowheads) and the time dependent x-position of the centroid of the dominating cavity (open arrowheads). As the acoustic mirror attracts the dominating CB, so is the location of the CSW emission during subsequent collapses translated in the direction of the mirror’s apex, which in turn causes the migration of the acoustic focus away from the acoustic mirror.

The displacement of the CB at its first collapse, normalized to the maximum size of the bubble, is well described by the empirical expression 3.7ζ2/3, where ζ is the dimensionless anisotropy parameter of the bubble defined as ζ = –0.195γ–2, where the negative sign corresponds to the migration of the CB towards the flat boundary [47]. In the present experiments, the anisotropy parameter equals –0.0061, a value 33 times larger in magnitude than the anisotropy induced by the gravity. The normalized displacement extracted from Fig. 5 (B2) is 0.19. This value is larger than 0.12, which corresponds to the normalized displacement for a flat rigid boundary and is given by the above empirical formula. If the CB was generated isotropically, by a point-like plasma, this evidence would support the conclusion that a concave solid surface in the present geometrical arrangement attracts the first collapse of the CB more than a flat boundary. However, such a conclusion might be too hasty, since a large asymmetry is already introduced into the CB growth by the elongated plasma as is seen in Fig. 4 (the inset of 1M).

After the first collapse, the CB assumes an asymmetric heart-like shape pointing towards the ophthalmic lens Fig. 5 (B3-C3). Such a shape of the cavity is caused by the faster collapsing distal wall compared to the proximal one, resulting in the formation of the liquid jet which drives the funnel shaped protrusion, an elongated bubble wall containing the jet, until its energy is used up [51]. After the second rebound, the shape of the CB again adopts the heart-like shape [Fig. 5 (D1-D3)].

A SW interaction with a CB also introduces similar asymmetry into the late bubble collapse and early rebound phase. The temporal shape of the BSW and CSW is a strong monopolar compression. Upon the collision of such a positive pressure SW with the CB, the liquid jet is formed in the direction of the SW propagation [44]. This is however not the case in the current experimental arrangement. Here, the emitted SW reflects from the PMMA without changing the phase, because it reflects from the acoustically denser material (Z1 = 1.49 MRayl < Z2 = 3.24 MRayl). After passing the acoustic focus, it experiences a Gouy phase shift of π, inverting the polarity and transforming the compressive SW into a rarefactional SW [52]. As the compressive SW pushes the proximal CB wall toward the distal one, so the rarefactional SW pulls the proximal wall away from the distal one. This is however not enough to presume that a collision of the negative pressure SW induces a liquid jet opposite to the direction of its propagation. This passage is meant to stress the fact that there are two contributions that drive the liquid jet and that both influence the collapse time. However, if the SW is continuously diverging such as when it is reflected from a flat boundary and then impinging back on the CB, no perceptible effect of the SW on the CB dynamics was observed [47].

4.3. Shock wave propagation

The BSW is emitted from the elongated plasma Fig. 4 (the inset in 1M). In the very beginning of its propagation Fig. 4 (the inset in 1M), it assumes an ellipsoidal shape, but soon the small difference between the unequal axis lengths are no longer discernable and one may consider the BSW as a spherically expanding acoustic transient [Fig. 4 (1M-4M, 1T-4T) and Fig. 5 (A1)].

The solid angle of the BSW missing the acoustic mirror continues its spherical expansion [Fig. 4 (5T-8T, the green line)]. The rest of the BSW that enters the aperture of the mirror is reflected [Fig. 4 (5T-12T, the red line)] from the concave surface and also scattered from the mirror’s edge [Fig. 4 (5T-12T, the blue line)]. The reflected BSW is converging [Fig. 5 (A2), the yellow arrow], building up in pressure amplitude, while the scattered BSW is toroidally diverging, getting weaker as it advances.

The BSW is also partially transmitted from the liquid environment into the solid PMMA lens, where shear elastic modes are allowed to propagate [6]. Even though the BSW propagating within the ophthalmic lens is not visualized in our experiments, the leakage of its longitudinal and share modes back into the water is seen in Fig. 4 (5M). Additionally, the interface-propagating Scholte wave is also observed lagging behind with a velocity of 1058 m/s (calculated from the exact solution [53]). The SW transients that are discernable in the water in the geometric shadow zone are: the P-head wave (the straight wavefront; the left-hand side yellow arrow) originating from the P-wave in the solid, the bulk acoustic wave (the arc-like wavefront connecting the BSW that missed the aperture with the S-wave in the solid; the central yellow arrow) originating from the S-wave in the solid and the Scholte wave confined to the interface (the right-hand side yellow arrow). Based on the distance these waves have travelled within the lens compared to the distance traversed by the BSW in the same time in water, one can determine the P-wave velocity α2 and the S-wave velocity β2.

The compressional BSW transmitted at the water/PMMA posterior surface as a compression, reflected by the PMMA/air anterior surface as a rarefaction and then retransmitted at the PMMA/water surface as a rarefaction can be seen in Fig. 4 (12M, the yellow arrow) as a slightly divergent wavefront.

In Fig. 4 (5M, 6M, 5T, 6T, the red line) the reflected BSW converges, it reaches the acoustic focus in (7M, 7T, the red line) and begins to spread out in (8M-12M, 8T-12T, the red line).

Another SW reflection is seen in Fig. 4 (9M, the upper yellow arrow). This is the SW reflected by the extruded ring on the lateral side of the lens, visible in the images as a vertical line.

The converging CSW are also clearly visible. In Fig. 5 (B4), the first CSW has just arrived to the acoustic focus, while in Fig. 5 (D1), the second CSW had been captured before it reached the acoustic focus.

4.4. Secondary acoustic cavitation

A keen eye immediately observes the inception of small bubbles near the acoustic focus [Fig. 4 (8M-11M) and Fig. 5 (A3, the left-hand side yellow arrow)] soon after the mirror-reflected BSW overpasses the focus and commences to diverge. Notice, that during its initial spherical expansion, the compressional BSW does not produce any secondary cavitation.

The secondary inertial cavitation takes place within the anterior laser cone (the dark magenta cone in Fig. 1) where the negative pressure in the acoustic focus exceeds the cavitation threshold. This volume of the water differs from the rest of the water since it has been illuminated and preheated by the excitation pulse [54]. We hypothesize that some of the laser pulse energy has been deposited within the illuminated cone where nanoscopic absorbing impurities were heated up beyond the boiling point, forming water vapor-filled nanobubbles, much smaller in size than the camera pixel size and thus invisible by the presented visualization techniques. Other descriptions of a more homogeneous seed population (remnant water vapor microbubbles produced by the preceding laser breakdowns in the same water tank [55] or stable gas nanonuclei [9], [56]) that do not take into account the position coincidence of the anterior laser cone and the secondary cavitation fail to describe the formation of the secondary cavitation predominantly on the laser path such as when the laser breakdown is generated in water close to its free surface where small secondary bubbles appear within the laser path after the shock wave reflected from the free surface overpasses the volume irradiated by the laser pulse [19], [57]. Thus, the secondary cavitation observable in the acoustic focus occurs when the following two requirements are met: (i) the acoustic focus must be located in the illumination cone of the excitation laser and (ii) the SW must be transformed from the initial positive pressure monopulse into a pulse that also has a large negative phase [12].

Here, the cavitation threshold, defined by the peak negative pressure, has a significantly less negative value compared to the similar experimental threshold of about –25 MPa within the water outside the pre-illuminated laser cone [55] or the thresholds of around –200 MPa predicted by the classical nucleation theory for homogeneous nucleation [9].

The small bubbles within the secondary cavitation cloud collapse and emit feeble SWs that can be seen in Fig. 4 (10M, 11M), but not before. The cloud of secondary bubbles reappears again after the crossing of the BSW reflected from the anterior surface of the ophthalmic lens Fig. 4 (12M, the yellow arrow). The measured distance between the two vertical yellow dotted lines (right: the BSW reflected from the posterior surface; left: the BSW reflected from the anterior surface) agrees with the additional effective path the BSW had to travel within the lens.

The small secondary bubbles never grow larger than 80 μm in radius which limits their period of oscillation, using the linear radius-collapse time relationship of Rayleigh [Eq. (3)], to 15 μs. For this reason, the prevailing time during the first oscillation of the main CB is free from visible secondary cavitation near the acoustic focus [see Fig. 5 (A4, B1-B3)]. The critical initial radius of the nanobubbles that can be expanded to visible size by the negative pressure of the SW is estimated to be in the order of 3 nm [9], [56].

During the first collapse of the CB, the first CSW is emitted from the distance aC1. When its propagation is in question, it lives a similar life as the initial BSW. However, its impact on the secondary cavitation is considerably more prominent. The gaseous aggregated volume of the secondary cavitation caused by the first CSW is much larger than the one triggered by the BSW. This is clearly visible when Fig. 5 (C1, C2) is compared to Fig. 5 (A3).

Both, the BSW and the first CSW are relatively similar in shape and in pressure amplitude [14], [47], but their effects on the here described secondary acoustic cavitation differs. As the BSW crosses the acoustic focus, some of its mechanical energy is transferred to the inflation of the cloud of small bubbles. Note that as Fig. 5 presents a single event, one can observe the memory effect of the secondary cavitation. Namely, the small bubbles acoustically triggered by the first CSW appear at the same locations as the BSW induced ones, but the latter are larger in size. It looks like as if the BSW has altered the initial bubble seeds in a way that the first CSW is then able to transfer even more energy to their second inflation episode.

The second CSW is smaller in pressure amplitude than the first CSW. Still it triggers the third inflation episode of small cavities near the acoustic focus [Fig. 5 (D2)]. The total volume of the gaseous structures near the acoustic focus is smaller than the one triggered by the first CWS but larger than the one initiated by the BSW. Compare Fig. 5 (D2) to Fig. 5 (C1, C2) and to Fig. 5 (A3).

The dominant CB is not the only cavitation entity that launches SW during its collapses. The secondary cavitation bubbles are also emitting SW as they collapse. See for instance Fig. 5 (C3, D3) where a SW indicated by the yellow arrow is emitted from the focal volume. Collapsing secondary bubbles are also seen in Fig. 4 (10M-12M). As can be deduced from the measurements, using the described experimental parameters, the SWs emitted from the secondary bubble are too feeble to give birth to the tertiary cavitation after their refocusing.

4.5. Shock wave scattering on the bubble

In the present experiments, the BSW and CSW are much shorter in length (about 0.1 mm) compared to the maximum diameter of the main cavity (3.58 mm) but much longer in length compared to the nanonuclei. Once such short-length SWs impinge on the large CB, the whole bubble never experiences pressure rise or drop over its entire wall as is the case when it overpasses a nanobubble. From this perspective, SW interaction with a large cavity can be thought of as a scattering of an acoustic pulse on a large spherical obstacle. A general conclusion can be drawn: if the length of the SW is much longer than the CB diameter, the SW-CB interaction will affect the CB more than the SW [56] while just the contrary can be stated if the length of the SW is much shorter than the dimensions of the CB [58]. An intermediate case of a SWCB interaction with comparable SW and CB lengths can be found in the work of Sankin et al. [44].

It is known from the materials with voids that scattering of a short plane compressive pulse from a large cavity results in the reflection of a nearly spherical wave [59] while the transmitted wave experiences a delay in the geometric shadow zone of the cavity [60]. The delay of the transmitted BSW can be appreciated in Fig. 5 (A3, the right-hand side yellow arrow).

Once the incident wave becomes tangent to the cavity, it creeps around it into its geometric shadow zone. The creeping wave propagates on the cavity surface and is being attenuated by leaking the energy back into the surrounding medium [55], [61]. The same effect is seen in Fig. 4 (9M-12M) during the BSW interaction with the CB.

Before the arrival of the BSW which is reflected from the acoustic mirror, the edge SW is the first to interact with the CB [Fig. 4 (9M)]. A reflected SW is seen to be emitted by the CB (the yellow arrow in the inset). A similar event takes place when the already divergent, mirror-reflected SW impinges on the CB [Fig. 4 (10M)]. In the inset of this frame, one can see three reflected SWs (the three yellow arrows). The outermost is emitted by the edge SW, the innermost by the collision of the mirror-reflected SW propagating near the optical axis, while the central one originates from the anterior point of the CB starting from the moment when the funnel bottom of the edge SW hits the CB. As opposed to the initial point-emission of the inner two CB-reflected SWs from the anterior point of the CB, the outermost one begins to be emanated on a circle where the funnel-shaped edge SW firstly touches the CB wall. The initial phase of the SW-CB interaction, similar to the initial phase of the mirror-reflected SW interaction with the CB from this work, can be found in the works of Quinto Su and Ando [55] and Oguri and Ando [58].

Observing this complex scattered pattern of SWs, a few interesting observations are worth being brought to attention. The amplitude of the transmitted SWs is smaller in geometric shadow zone, the closest the SW is to the center of the shadow [Fig. 4 (10M-12M)]. No visual effects of the SWs on the CB are noticeable during their interaction with it. Also, no cavitation inception just in front of the CB can be perceived in Fig. 4 due to the backscattering of the SWs. This is mentioned, because pressure wave backscattering is an important mechanism in bubble cloud formation in the HIFU interaction with a preexisting CB [9], [58]. The SW transmitted into the gaseous phase of the CB cannot be visualized with the presented techniques. The wave-guided propagation of the SW on the CB surface seems to move faster than the acoustic velocity in the bulk α1 [see the inset in Fig. 4 (9M)]. It would be interesting to understand what causes this speed-up, because it is known that the near vicinity of the CB (both within the gaseous phase and outside, in the liquid phase) experiences huge variations of pressure, flow velocity and even temperature. In this perspective, small-length SW could serve as probes for testing the CB phase interface. Here, the probing tool, the SW, could as well be generated by the very object to be probed, the CB.

4.6. Pressure buildup at the bubble collapse

Already in 1917, Rayleigh wrote down the expression for the distribution of the pressure in the liquid surrounding the collapsing CB. He found that just before the collapse, when the CB has a radius of , the maximum pressure of is generated at a distance from the center of the bubble [29]. For example, when the CB deflates to 15% of its maximum radius, a maximum pressure 47 times larger than the ambient pressure is reached at 1.59r. From this CB size it takes only 0.0047tc for the cavity to implode. In our case, this is only 0.8 μs.

This transient pressure buildup is manifested in the measurements either as a positive pressure pedestal preceding the CSW in the pressure waveforms measured by optical or piezo hydrophones [14], [47] or as a lens-like region surrounding the CB just before it collapses, bending the illuminating light, and forming shadows and image distortions [47], [62], [63], [64].

In addition to the pressure rise distribution near the collapsing CB, the elevated pressure buildup also relaxes radially away from the CB wall. Then, the CSW is launched supersonically from the point of implosion. The propagation of pressure waves at elevated pressures is faster than at an ambient pressure. It was found that this effect shortens the time of flight of the CSW to the fixed position of a pressure sensors compared to the BSW [47], [62].

Using the schlieren approach for the visualization of the pressure gradients, we found that optically, the water in front of the BSW and the first CSW differs substantially [compare Fig. 5 (A1) with Fig. 5 (B2)]. The first CSW is surrounded by an elevated pressure, which falls off radially away from the CSW and approaches the static pressure in the far field. This is seen in Fig. 5 (B2) as the dark region on the right-hand side of the distal CSW front and as the pale region on the left-hand side of the proximal CWS front. Note that the schlieren images display only the pressure gradients in the x-direction, because the knife edge was used in the vertical position. Similar full-gradient schlieren images were numerically obtained by Yin et al. [65] and Koukouvinis et al. [66] using a more realistic model that, most importantly, allows for compressible effects and thus also predicts the emission of the CSW. The pressure profiles calculated at the time instant soon after the emission of the CSW indicate that the opposite pressure gradient is to be expected between the CSW and the CB wall [67]. This is also clearly visible in the schlieren image in Fig. 5 (B2).

The visual thickness of the dark region in the right-hand side of the CSW front in Fig. 5 (B2) is estimated as 1.6 mm, which means that the outermost, visually still discernable dark band was emitted roughly 0.8 μs before the collapse, when the CB radius was about 15% of its maximum size. This happened after the frame B1 in Fig. 5 had been captured, that is why the CB in this frame is not surrounded by the same type of a light deflecting shell of pressurized water as in Fig. 5 (B2).

In fact, the water in the near vicinity [r, 1.59r] of the CB in Fig. 5 (B1, the yellow arrow) deflects the probing light in the opposite direction than the water surrounding the CWS in Fig. 5 (B2). This corresponds to a shell of water with a pressure steeply rising from pin at the CB wall r to pmax at the location of the pressure maximum at 1.59r. Farther out, the fall-off pressure gradient from pmax to the far field pressure has a much smaller absolute value [48], [66] and is not discernable due to the sensitivity limit of the presented schlieren technique.

4.7. Collapse watermark

Once the dominant cavity translates away from the implosion site of the first CB oscillation, water fills up this region and reveals that it has been altered by a persistent (at least in the first 1 ms after the breakdown) watermark created during the first collapse. Two important features of this average water density perturbation are seen [see for instance Fig. 5 (D4, the yellow arrow)].

The first are the streamers, the vapor-filled filaments, matching the direction of the water flow at the late stage of the collapse. These lines originate from the small satellite cavities surrounding the dominant CB. The small cavities are already present in the growth stage of the dominant CB and become severely elongated in the late stage of the collapse. These streamers can be seen as the corona-like spikes extending radially out from the collapsing CB in Fig. 5 (B1). The streamers are often present in the shadowgraphs when larger CBs collapse near various surfaces [19], [68]. Once they form, they persist at the same position in the whole lifetime of the dominant CB.

The second constituent of the collapse watermark is the 1mmwide, low-density center, visible in the schlieren images as the dark-pale pair of lobes as one goes from the left-hand side towards the right-had side of this region [see for instance Fig. 5 (D4, the yellow arrow)]. The reversal of the refractive index gradient within this area suggests that it has a lower average density center than the surrounding liquid. Very likely, this reduction of the average density is due to the presence of a cloud of unresolvable microbubbles. Indications of such a rarefied volume could also be perceived by careful examination of the shadowgraphs and interferograms obtained by Ward and Emmony [64].

5. Conclusion

The optical breakdown in the vicinity of a concave boundary was visualized with shadow photography and schlieren technique using an adaptive illumination approach. The experimental setup mocked the response of a human eye after the application of a 15-mJ laser pulse within the actual human eye. A simple theory based on the geometrical acoustics was developed to estimate the spatiotemporal position of the propagating shock waves (SWs). This nonparametric study reveals complex dynamics of light deflecting structures, mainly consisting of water-borne shock waves and cavitation bubbles (CBs) of various sizes and shapes.

The visualization of repeatable events with either the shadowgraphy or the schlieren method exposed their pros and cons. The schlieren approach enabled visualization of pressure gradients unperceivable by the shadow imaging. The examples are the pressure distributions during the final stage of a collapse and the initial stage of the rebound, and the remnant lower average density volume at the location of the first collapse. On the other hand, much sharper images of the SW fronts were obtained using the shadow imaging.

The response of the water after such a vigorous deposition of the laser energy in the plasma located in the optical focus consists of numerous interesting phenomena that were described in detail. Some of these phenomena are also present when the breakdown is generated near a flat or a convex boundary, while especially the acoustic focusing and the generation of the aggregates of secondary cavities near the acoustic focal volume are specific for optically generated bubbles near a concave surface. It was found that the first collapse shock wave (CSW) induces the strongest secondary cavitation, followed by the second CSW and then the breakdown shock wave (BSW) whose effect is the least pronounced. The negative pressure threshold for the inception of visible-sized cavities is less negative within the volume of water illuminated by the excitation pulse than outside this volume.

The shock wave scattering on the dominant cavitation bubble revealed the presence of the transmitted shock wave in the geometric shadow zone, the emission of a nearly spherical shock wave by the CB wall and faster SW propagation along the CB interface compared to the acoustic SW propagation in the bulk.

The first oscillation of the CB generated at a non-dimensional stand-off distance of 5.7 is about 2% shorter than the estimate for the infinite liquid and about 7% shorter than the estimate for the same stand-off distance from the flat rigid boundary. As the CB is attracted by the concave surface, the acoustic focus during the subsequent collapse moves away from the acoustic mirror. In the present case, breakdown-first collapse displacement is about 60% larger compared to the case if the boundary were flat. Two mechanisms that possess the ability to induce axial asymmetry on the CB were identified. One is the presence of the concave boundary on the other is the interaction of the mirror-reflected SW with the CB.

The transmission of the SW into the PMMA lens was visualized near the lens-water interface, revealing the P-head wave and the Scholte wave.

The implications of this work extend from ophthalmology, the mock-up attempt treated here, to any technology that deals with cavitation near inward curved, conically depressed surfaces such as cavitation peening and cavitation erosion.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tomaž Požar: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Vid Agrež: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Rok Petkovšek: Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P2-0270 and project Nos. L2-9240 and L2-9254).

Funding

This research was funded by the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P2-0270 and project Nos. L2-9240 and L2-9254).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105456.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tomita Y., Robinson P.B., Tong R.P., Blake J.R. Growth and collapse of cavitation bubbles near a curved rigid boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 2002;466:259–283. doi: 10.1017/S0022112002001209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Craxton R.S., Anderson K.S., Boehly T.R., Goncharov V.N., Harding D.R., Knauer J.P., McCrory R.L., McKenty P.W., Meyerhofer D.D., Myatt J.F., Schmitt A.J., Sethian J.D., Short R.W., Skupsky S., Theobald W., Kruer W.L., Tanaka K., Betti R., Collins T.J.B., Delettrez J.A., Hu S.X., Marozas J.A., Maximov A.V., Michel D.T., Radha P.B., Regan S.P., Sangster T.C., Seka W., Solodov A.A., Soures J.M., Stoeckl C., Zuegel J.D. Direct-drive inertial confinement fusion: A review. Phys. Plasmas. 2015;22(11):110501. doi: 10.1063/1.4934714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apazidis N., Eliasson V. Shock Focusing Phenomena: High Energy Density Phenomena and Dynamics of Converging Shocks. Springer International Publishing. 2018 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-75866-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lou Y.Q., Shi C.H. Self-similar dynamic converging shocks - I. An isothermal gas sphere with self-gravity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014;442:741–752. doi: 10.1093/mnras/stu573. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sembian S., Liverts M. On using converging shock waves for pressure amplification in shock tubes. Metrologia. 2020;57(3):035008. doi: 10.1088/1681-7575/ab7f99. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong P. Shock Wave Lithotripsy. In: Delale C.F., editor. Bubble dynamics and shock waves. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2013. pp. 291–338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jagadeesh G., Prakash G.D., Rakesh S.G., Allam U.S., Krishna M.G., Eswarappa S.M., Chakravortty D. Needleless Vaccine Delivery Using Micro-Shock Waves. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(4):539–545. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00494-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauer U., Bürgelt E., Squire Z., Messmer K., Hofschneider P.H., Gregor M., Delius M. Shock wave permeabilization as a new gene transfer method. Gene Ther. 1997;4(7):710–715. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horiba T., Ogasawara T., Takahira H. Cavitation inception pressure and bubble cloud formation due to the backscattering of high-intensity focused ultrasound from a laser-induced bubble. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020;147(2):1207–1217. doi: 10.1121/10.0000649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downing M., Zamot N., Moss C., Morin D., Wolski E., Chung S., Plotkin K., Maglieri D. Controlled focused sonic booms from maneuvering aircraft. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1998;104:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu H., Yao A., Yao C.D., Gao J. Energy convergence of shock waves and its destruction mechanism in cone-roof combustion chambers. Energy Convers. Manage. 2016;127:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.09.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Požar T., Petkovšek R. Cavitation induced by shock wave focusing in eye-like experimental configurations. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2020;11:432–447. doi: 10.1364/BOE.11.000432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Požar T., Horvat D., Starman B., Halilovič M., Petkovšek R. Pressure wave propagation effects in the eye after photoablation. J. Appl. Phys. 2019;125(20):204701. doi: 10.1063/1.5094223. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauterborn W., Vogel A. Shock wave emission by laser generated bubbles. In: Delale C.F., editor. Bubble dynamics and shock waves. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2013. pp. 67–103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tagawa Y., Yamamoto S., Hayasaka K., Kameda M. On pressure impulse of a laser-induced underwater shock wave. J. Fluid Mech. 2016;808:5–18. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2016.644. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinibaldi G., Occhicone A., Alves Pereira F., Caprini D., Marino L., Michelotti F., Casciola C.M. Laser induced cavitation: Plasma generation and breakdown shockwave. Phys. Fluids. 2019;31(10):103302. doi: 10.1063/1.5119794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brujan E.A., Nahen K., Schmidt P., Vogel A. Dynamics of laser-induced cavitation bubbles near an elastic boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 2001;433:251–281. doi: 10.1017/S0022112000003347. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindau O., Lauterborn W. Cinematographic observation of the collapse and rebound of a laser-produced cavitation bubble near a wall. J. Fluid Mech. 2003;479:327–348. doi: 10.1017/S0022112002003695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Supponen O., Obreschkow D., Kobel P., Tinguely M., Dorsaz N., Farhat M. Shock waves from nonspherical cavitation bubbles. Phys. Rev. Fluids. 2017;2 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevFluids.2.093601. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dular M., Požar T., Zevnik J., Petkovšek R. High speed observation of damage created by a collapse of a single cavitation bubble. Wear. 2019;418–419:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.wear.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obreschkow D., Tinguely M., Dorsaz N., Kobel P., de Bosset A., Farhat M. The quest for the most spherical bubble: experimental setup and data overview. Exp. Fluids. 2013;54:1503. doi: 10.1016/10.1007/s00348-013-1503-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takayama K. Visualization of Shock Wave Phenomena. Springer. 2019 doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-19451-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrež V., Požar T., Petkovšek R. High-speed photography of shock waves with an adaptive illumination. Opt. Lett. 2020;45:1547–1550. doi: 10.1364/OL.388444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wexler A. Vapor Pressure Formulation for Water in Range 0 to 100 deg C – A Revision. J. Res. NBS A Phys. Ch. 1976;80A:775–785. doi: 10.6028/jres.080A.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.H.L. Heacock, Molded ophthalmic lens, patent: US 8,303,116 B2, 2012, DOI not found.

- 26.Panigrahi P.K., Muralidhar K. Schlieren and Shadowgraph Methods in Heat and Mass Transfer. Springer; New York: 2012. Laser Schlieren and Shadowgraph; pp. 23–46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Settles G.S. Schlieren and Shadowgraph Techniques: Visualizing Phenomena in Transparent Media, Springer, Berlin. Heidelberg. 2001 doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56640-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Settles G.S., Hargather M.J. A review of recent developments in schlieren and shadowgraph techniques. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2017;28(4):042001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6501/aa5748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rayleigh L. On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity. Philos. Mag. 1917;34:94–98. doi: 10.1080/14786440808635681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Plesset M.S. The dynamics of cavitation bubbles. J. Appl. Mech.-T. ASME. 1949;16:277–282. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kudryashov N.A., Sinelshchikov D.I. Analytical solutions of the Rayleigh equation for empty and gas-filled bubble. J. Phys. A-Math. Theor. 2014;47(40):405202. doi: 10.1088/1751-8113/47/40/405202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kudryashov N.A., Sinelshchikov D.I. Analytical solutions for problems of bubble dynamics. Phys. Lett. A. 2015;379(8):798–802. doi: 10.1016/j.physleta.2014.12.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mancas S.C., Rosu H.C. Evolution of spherical cavitation bubbles: Parametric and closed-form solutions. Phys. Fluids. 2016;28(2):022009. doi: 10.1063/1.4942237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin Y. Analytical solution for the collapse motion of an empty hyper-spherical bubble in N dimensions. Phys. Lett. A. 2020;384(6):126142. doi: 10.1016/j.physleta.2019.126142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Obreschkow D., Bruderer M., Farhat M. Analytical approximations for the collapse of an empty spherical bubble. Phys. Rev. E. 2012;85 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.85.066303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petkovšek R., Možina J., Močnik G. Optodynamic characterization of the shock waves after laser-induced breakdown in water. Opt. Express. 2005;13:4107–4112. doi: 10.1364/OPEX.13.004107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones F.E., Harris G.L. ITS-90 Density of Water Formulation for Volumetric Standards Calibration. J. Res. Nat. Inst. Stand. Technol. 1992;97:335–340. doi: 10.6028/jres.097.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bilaniuk N., Wong G.S.K. Speed of Sound in Pure Water as a Function of Temperature. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1993;93(3):1609–1612. doi: 10.1121/1.406819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christman D.R. General motors technical center Warren MI materials and structures lab, Dynamic Properties of Poly(methylmethacrylate) (PMMA) (Plexiglas), in. Defense Technical Information Center. 1972:1–48. https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/743547.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vogel A., Busch S., Jungnickel K., Birngruber R. Mechanisms of Intraocular Photodisruption with Picosecond and Nanosecond Laser-Pulses. Laser. Surg. Med. 1994;15(1):32–43. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1096-910110.1002/lsm.v15:110.1002/lsm.1900150106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Plesset M.S., Chapman R.B. Collapse of an initially spherical vapour cavity in neighbourhood of a solid boundary. J. Fluid Mech. 1971;47:283–290. doi: 10.1017/s0022112071001058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reuter F., Gonzalez-Avila S.R., Mettin R., Ohl C.D. Flow fields and vortex dynamics of bubbles collapsing near a solid boundary. Phys. Rev. Fluids. 2017;2 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevFluids.2.064202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohl C.D., Ohl S.W. Shock Wave Interaction with Single Bubbles and Bubble Clouds. In: Delale C.F., editor. Bubble dynamics and shock waves. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2013. pp. 3–31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sankin G.N., Simmons W.N., Zhu S.L., Zhong P. Shock wave interaction with laser-generated single bubbles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005;95 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.034501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhong P., Cocks F.H., Cioanta I., Preminger G.M. Controlled, forced collapse of cavitation bubbles for improved stone fragmentation during shock wave lithotripsy. J. Urology. 1997;158(6):2323–2328. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)68243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.W. Lauterborn, T. Kurz, R. Mettin, C.D. Ohl, Experimental and Theoretical Bubble Dynamics, in: I. Prigogine, S.A. Rice (Eds.) Adv. Chem. Phys., John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1999, pp. 295-380, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470141694.ch5.

- 47.Supponen O., Obreschkow D., Kobel P., Dorsaz N., Farhat M. Detailed experiments on weakly deformed cavitation bubbles. Exp. Fluids. 2019;60:33. doi: 10.1007/s00348-019-2679-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zevnik J., Dular M. Cavitation bubble interaction with a rigid spherical particle on a microscale. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;69:105252. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui P., Wang S.P., Zhang A.M., Liu Y.L. Spark Bubble Collapse near Non-flat Surfaces. In: Katz J., editor. 10th International Symposium on Cavitation (CAV2018) ASME Press; Baltimore, Maryland, USA: 2018. pp. 1–4. https://cav2018.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/Cui-Pu.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shervani-Tabar M.T., Rouhollahi R. Numerical study on the effect of the concave rigid boundaries on the cavitation intensity. Sci. Iran. 2017;24:1958–1965. doi: 10.24200/sci.2017.4286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lauterborn W., Ohl C.-D. Cavitation bubble dynamics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 1997;4(2):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S1350-4177(97)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feng S.M., Winful H.G. Physical origin of the Gouy phase shift. Opt. Lett. 2001;26:485–487. doi: 10.1364/Ol.26.000485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vinh P.C. Scholte-wave velocity formulae. Wave Motion. 2013;50(2):180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.wavemoti.2012.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schiffers W.P., Emmony D.C., Shaw S.J. Visualization of the fluid flow field around a laser generated oscillating bubble. Phys. Fluids. 1997;9(11):3201–3208. doi: 10.1063/1.869436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quinto-Su P.A., Ando K. Nucleating bubble clouds with a pair of laser-induced shocks and bubbles. J. Fluid Mech. 2013;733:R3. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2013.456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sankin G.N. Cavitation under spherical focusing of acoustic pulses. Acoust. Phys. 2006;52(1):93–103. doi: 10.1134/S1063771006010131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.W. Lauterborn, Laser-Induced Cavitation, Acustica, 31 (1974) 51-78, DOI not found.

- 58.Oguri R., Ando K. Cavitation bubble nucleation induced by shock-bubble interaction in a gelatin gel. Phys. Fluids. 2018;30(5):051904. doi: 10.1063/1.5026713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomita Y. Interaction of a Shock Wave with a Single Bubble. In: van Dongen M.E.H., editor. Shock Wave Science and Technology Reference Library: Multiphase Flows I. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2007. pp. 35–66. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun K.H., Sun C.M., Li J.W., Wang Z.Y., Gao W., Fan Q.C. Study of Laser-Generated Longitudinal Waves Interacting with an Internal Spherical Cavity by Use of a Transmission Time Delay Method. Int. J. Thermophys. 2020;41:81. doi: 10.1007/s10765-020-02666-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ying C.F., Zhang S.Y., Shen J.Z. Scattering of ultrasound in solids as visualized by the photoelastic technique. J. Nondestr. Eval. 1984;4(2):65–73. doi: 10.1007/BF00566398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Supponen O., Obreschkow D., Farhat M. High-speed imaging of high pressures produced by cavitation bubbles. Proc. SPIE. 2019;11051:1105103. doi: 10.1117/12.2523259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomita Y., Shima A. Mechanisms of Impulsive Pressure Generation and Damage Pit Formation by Bubble Collapse. J. Fluid Mech. 1986;169:535–564. doi: 10.1017/S0022112086000745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward B., Emmony D.C. Interferometric Studies of the Pressures Developed in a Liquid during Infrared-Laser-Induced Cavitation-Bubble Oscillation. Infrared Phys. 1991;32:489–515. doi: 10.1016/0020-0891(91)90138-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yin J., Zhang Y., Zhang Y. Numerical study of a laser generated cavitation bubble based on FVM and CLSVOF method. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth and Env. Sci. 2019;240:072021. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/240/7/072021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koukouvinis P., Gavaises M., Supponen O., Farhat M. Numerical simulation of a collapsing bubble subject to gravity. Phys. Fluids. 2016;28(3):032110. doi: 10.1063/1.494456110.1063/1.4944561.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hickling R., Plesset M.S. Collapse and Rebound of a Spherical Bubble in Water. Phys. Fluids. 1964;7:7–14. doi: 10.1063/1.1711058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang M., Chang Q., Ma X., Wang G., Huang B. Physical investigation of the counterjet dynamics during the bubble rebound. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019;58:104706. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.