Abstract

Based on the Government Work Report of 265 prefecture-level cities in China from 2004 to 2015, this article combines economic growth expectations data and keyword capture to explore the relationship between government economic growth expectations and air pollution. The main results are as follows: (1) The economic growth expectations of local governments, and the “increment” between prefecture-level and provincial governments’ growth expectations for economic growth have significantly increased air pollution. The certainty and completion degree of economic growth expectations have different effects on air pollution, and the impact of the expected rigid constraint and overfulfilled degree on air pollution are prominent. When the city’s real economic growth exceeds 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% of growth expectations, respectively, SO2 emissions will increase by 10.577%, 10.671%, 11.825%, and 16.296%, and PM2.5 concentration will increase by 2.115%, 2.503%, 3.592%, and 4.421%. (2) The government’s annual economic growth expectations have different effects on different types of technological innovation. For every 1% increase in the government’s economic growth expectations, the green technology will be reduced by 0.956% which exacerbates regional air pollution. Furthermore, the green technology can explain 6.5% of air pollution induced by government economic growth expectations.

Keywords: Economic growth expectations, Certainty and completion degree, Air pollution, Green technology

Introduction

Air pollution and economic development are two intertwined topics, but the two tend to run in opposite directions. Since the reform and opening up in the late 1970s, China’s extensive economic development has driven high economic growth while also bringing about continuous environmental degradation. China’s GDP in 2019 has reached 99.1 trillion yuan, which is only lower than that of the USA, and China’s GDP per capita has exceeded 10,000 US dollars. However, accompanied by rapid growth is the high consumption of fossil fuels, which has led to the higher emissions of sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and soot in China. “China’s Economic and Ecological Gross Product Accounting Development Report 2018” pointed out that among 338 prefecture-level cities in China, the proportion of air quality exceeding the standard is as high as 64.2%. There have been acid rains in 102 cities, and as many as 86.2% of water quality monitoring stations showed that the water pollution exceeded the standard.

Nowadays, the raging of COVID-19, the stagnation of the world economy, and the increase in the uncertainty and complexity of the external environment have made air pollution control a more challenging problem. The report of the 19th People’s Congress of the Communist Party of China pointed out that the Chinese economy is currently in a critical period of transition from high-speed growth to a high-quality development stage. In the transformation stage of high-quality economic development, promoting green sustainable development is an important measure to promote the construction of ecological civilization and high-quality economic growth. However, a phenomenon that deserves attention is that the expected slowdown in economic growth will trigger a series of chain reactions. However, one noteworthy phenomenon is that the transformation of economic development from the extensive mode of pursuing growth to the Connotative mode of pursuing green and high-quality development that will trigger a series of chain reactions. Local governments have difficulty in making decisions on whether to maintain growth or green development. Traditional inertia is more likely to make the local government’s implementation of green steering insufficient. From 2004 to 2014, the annual economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities are greater than 10%, and the prefecture-level cities have an “increment” phenomenon compared to the economic growth expectations of their provinces. From the perspective of the “increment” of economic growth expectations, before 2013, the city’s economic growth expectations were higher than the provincial growth expectations by more than 2% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Typical facts of economic growth expectations

| Variables | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial economic growth expectations (%) | 9.65 | 10.15 | 10.71 | 10.22 | 10.66 | 9.31 | 7.88 |

| City economic growth expectations (%) | 12.52 | 13.10 | 13.69 | 12.71 | 12.98 | 10.36 | 8.51 |

| City-provincial increment range (%) | 2.87 | 2.94 | 2.98 | 2.49 | 2.32 | 1.05 | 0.63 |

As a government-led economy, China’s Government Work Report plays an important role in maintaining economic growth and green development. In fact, the government has taken note of the environmental impact that economic targets may have. In the 2016 Government Work Report, the national economic growth expectation is between 6.5 and 7%, which is the first time to adopt the concept of a range that is not explicitly required for economic growth. Although economic growth targets have already taken into account the real economic growth rate of the previous year (Liu et al. 2019), but in face of external economic growth pressure, and under the promotion system of officials, economic growth performance is regarded as an important indicator of officials’ ability assessment (Su et al. 2012; Landry et al. 2017). In order to get extra attention from the superior government, the local government officials always make more higher growth target relative to the superior government in order to achieve excellent governance performance and achieve official promotions (Wu et al. 2013; Li et al. 2019).

Literature about economic growth expectations, which is a special government behavior, mainly focuses on its economic growth effect (Li and Zhou 2005; Xu and Liu 2017; Xu et al. 2018). Xu and Liu (2017) proved theoretically that under certain conditions, the government’s economic growth expectation can affect economic growth by forcing the allocation of resources. However, the economic growth expectation has a differentiated effect on the input of different types of production factors. Local governments’ pursuit of short-term economic results is more about increasing capital investment and less about technological progress, which is more important in the long run. Empirical results show that local governments have a significant effect on boosting economic growth by increasing the overall investment rate of the society. For every 1% increase in economic output, the average investment rate will increase by about 36% (Xu et al. 2018). Yu and Pan (2019) try to explain the long-term development of China’s service industry from the perspective of economic growth expectations. They found that the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities significantly inhibited the upgrading of industrial structure. Especially when local governments make hard-binding economic growth expectations with words such as “exceed,” “over,” “beyond,” “higher than,” and “ensure,” their industrial structure restraining effect is particularly obvious. Liu et al. (2019) use a manual dataset of economic growth targets of China to test the inhibitory effect of the growth target on public service expenditure and business cycle. And they found the growth target hinders long-term economic growth.

Meanwhile, economic growth is always accompanied by air pollution, and the consequences of non-green economic growth are more serious. How to internalize the externality of air pollution which is a negative externality product of economic production and play the role of the government in the process of air pollution control have always been the focus of academic attentions. A large number of studies take the perspective of policy intervention and innovation compensation as the starting point (Gray and Shadbegian 2003; Hamamoto 2006), and analyze the pollution reduction effects of environmental regulation policy (Blackman and Kildegaard 2010; Zheng and Kahn 2017), such as carbon taxes or sewage charges (Aghion et al. 2016; Gao et al. 2019), carbon trading, and innovation subsidies (Dong et al. 2019; Hou et al. 2019). Hu et al. (2020) use DID model to measure the impact of CO2 emission trading policy on CO2 in industrial sector, and point out that CO2 emission trading policy can reduce the CO2 emission and energy consumption. Hou et al. (2019) also find that the SO2 emission trading policy effectively decreases SO2 emissions. Wang and Wei (2019) find that the “Water Ten Plan” effectively reduced water pollution. Gao et al. (2019) employ the Stackelberg game models to examine the emission reduction effect of the environmental tax deduction (ETD). The results show that only in a moderate level of environmental concern and emission standard the ETD can work. Some literature focuses on the impact of technology improvement on pollution abatement (Chen and Duan 2016; Xu et al. 2019; Adkin 2019). And found that the regional technical efficiency and technology improvement can effectively reduce SO2, NOx, and PM2.5.

It is certain that the improvement of air pollution and environmental quality is inseparable from the role of technology progress. How environmental policies encourage technological progress towards a green direction has gradually become the focus of attention (Acemoglu et al. 2012; Aghion et al. 2016). Acemoglu et al. (2012) introduce carbon taxes and subsidies in an endogenous and directed technical change model with environmental constraints to deduce the impact of environmental policy on technology progress and environmental quality. And they find the taxes and subsidies can also help the switch to clean innovation and improve the quality of environment. Aghion et al. (2016) construct a new panel data set of patents containing dirty technologies, cleaner technologies, and gray technologies to examine whether fuel prices (carbon taxes) can change a firm’s technical direction. And find that carbon taxes can effectively stimulate clean innovation whereas depress dirty innovation. Dong et al. (2019) use a two-sector technological model to investigate the effect of subsidies and directed technologies on environmental quality, and find that clean R&D subsidies can effectively change technological direction to improve environmental quality in the long run. Milani (2017) examines empirically the impact of environmental regulations on R&D innovation in manufacturing industries of OECD countries, and finds that pollution intensity and the relative ease of relocation are the determinants of the effect of environmental policy on innovation. As environmental policies become more restrictive, pollution-intensive industries innovate less and immobile industries innovate more than mobile industries.

According to the existing literature, the research on government behavior and air pollution has two main characteristics: First, it pays attention to the effects of environmental policies on pollution control and technological progress (Harrison et al. 2015; Albrizio et al. 2017), such as carbon tax (Acemoglu et al. 2012), fuel prices incentivize (Dechezlepr et al. 2011; Aghion et al. 2016), emissions trading system (Hu et al. 2020), and the formation mechanism of environmental Kuznets curve and its relationship testing (Pasten and Figueroa 2012; Buehn and Farzanegan 2013; Dimitra and Efthimios 2013). The second is research on the relationship between government behavior and environmental pollution. Such research mainly focuses on fiscal decentralization (Lipscomb and Mobarak 2017), government competition (Cai et al. 2016; He et al. 2018), and official promotion tournaments (Leitao 2010). The literature which explains the air pollution problems from the perspective of government economic behavior in government-led economies is rare.

This paper explores the impact of government economic expectation on air pollution by grasping the key words of economic expectation and its data modification description in the Government Work Report from the specific government behavior of economic expectation. Possible marginal contribution lies in the following: first, different from the traditional literature which focuses on the effects of environmental regulation policy on air pollution and the economic effect of the government economic growth expectations behavior, this paper explains the cause of air pollution in government-led economies according to the behavior of the prefectural government annual economic growth expectations. The effect of the government’s economic expectation on air pollution is reinterpreted, which provides a new explanation for how to develop green economy in a government-led economy. Second, based on the certainty and completion degree of the government’s economic growth expectations, this paper tests the differentiated consequences of different types of growth expectations on air pollution. Thirdly, from the perspective of technological progress, especially the progress of green technology, this paper explores whether the government’s economic expectation will affect air pollution through technological innovation, and further measures the contribution of technological progress to air pollution control referring to the ideas of Gelbach (2016).

The paper is organized as follows. The second section is the research design and the data source explanation, introduces the index selection and the model construction basis. The third section is the test of the relationship between the government’s economic growth expectation and air pollution. We adopt the panel data double-fixed effect model and the instrumental variable method to explore the environmental effect of the government’s economic expectation. The fourth section is the heterogeneity analysis, which analyzes the different influences on air pollution from the two aspects of economic expectation certainty and completion degree. The fifth section is the analysis of the emission reduction effect of different technological progress, mainly investigating how the government’s economic growth expectation influences regional air pollution through the effect of technological progress. The sixth part is the basic conclusion.

Model and data source description

Econometric model

This paper combines panel data of 265 prefecture-level cities in China with a span of 12 years from 2004 to 2015 to examine the impact of annual economic growth expectations of prefecture-level municipal governments on air pollution and the role of green technological progress. The annual economic growth variables show obvious time trends, and there is obvious heterogeneity in the economic development of various cities in China. It is necessary to control the time trend and regional heterogeneity of the sample data (Fabrizi et al. 2018). Therefore, we construct the dual fixed-effects model of time and region of panel data, and use the least square estimation method of panel data to make empirical test. The econometric model is set as follows:

| 1 |

where the dependent variable polluit is the air pollution level for city i of year t, which is characterized by urban sulfur dioxide emissions (SO2) and smog pollution concentration (PM2.5). expit is the annual economic growth expectation for city i of year t, ρ measures the effect of the urban economic growth expectation on air pollution. Xit is the set of control variables. In formula (1), δ is the intercept term that does not vary with individuals, βX is the estimated coefficient of the control variable X, ϑt is the time fixed effect, μi is the city fixed effect, and εit is the random error term.

Regarding the main explanatory variable, the government’s annual economic growth expectation exp, prefecture-level cities generally publish annual Government Work Report at the beginning of each year, announcing the annual economic growth expectations approved by the local people’s congress. The economic growth expectation is the pre-expected economic goals and work plan that the local government discloses to the local people’s congress at the same level. This paper collects work reports of various prefecture-level municipal governments by hand, and uses the annual economic growth rate in the work reports as the indicators of regional government economic growth expectations. Moreover, the difference between the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities and their province is used to characterize the degree of increment between prefecture-level cities and their province (Liu et al. 2019).

In order to control the impact of other factors on air pollution, other variables are also introduced in the econometric model, which mainly include (1) economic development, which is characterized by urban economic output (gdp) and urban average wage level (wage). Generally speaking, the higher the economic growth and the income level of residents, the higher the economic transformation needs and the environmental needs of residents, the greater pressure of green economic shift on the government and enterprises (Ito and Zhang 2015; Sun et al. 2016), which in turn affects the enterprises’ pollution behavior and the green direction of technology progress. (2) Foreign direct investment (fdi), which is characterized by the ratio of the city’s actual use of foreign capital to GDP. There are two main points of view on the effect of foreign direct investment on the environment: the first is the “pollution refuge” hypothesis. Such studies believe that some countries, especially those with weak economic development, tend to use lower environmental standards to attract foreign investment, which leads to structural lock-in of low-end economic development (Fredriksson et al. 2003) and is not conducive to green technology progress and increase air pollution in the host country. The second is the “pollution halo” hypothesis. Such views suggest that foreign direct investment can bring advanced management standards and green technology spillovers, which is conducive to regional pollution reduction (Daniel et al. 2019). (3) Government intervention (gov) which is measured by the ratio of local government general budget fiscal expenditure to GDP. The higher the proportion of fiscal expenditure in GDP, the greater the intensity of government economic intervention. (4) R&D expenditure (rd). It is characterized by the proportion of scientific expenditure in each region to GDP. (5) Green technology patent gtech. According to international patent classification of green patent list (http://www.wipo.int/classifications/ipc/en/est/) in the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), we manually search for the relevant data by setting types of patents, IPC classification codes, and addresses of inventors from the State Intellectual Property Office (Lin et al. 2018).

This article mainly explains the impact of economic growth expectations on air pollution. The “promotion championship” mechanism for local officials’ promotes the officials’ internal pursuit of economic growth expectations, resulting in different types of officials have different demands for economic growth goals. To this end, this article controls some of the individual characteristics of major local officials, such as gender, age, education, and professional background. Table 2 is the descriptive statistics of the data of each variable.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables

| Variable symbol | Variable name | Measurement | Mean | Min | Max | Obs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide emissions | Natural logarithm of regional sulfur dioxide emissions | 10.652 | 0.693 | 13.115 | 2232 |

| PM2.5 | Haze concentration | Natural logarithm of regional haze concentration | 3.591 | 1.707 | 4.520 | 2232 |

| exp | Economic growth expectations | Annual expected economic growth rate in local Government Work Report | 0.125 | 0.060 | 0.350 | 2232 |

| sjm | Increment | The difference of economic growth expectation between prefecture-level cities and their provinces | 0.023 | -0.060 | 0.210 | 2232 |

| gdp | Economic output | Natural logarithm of local economic output | 16.084 | 13.086 | 18.890 | 2232 |

| fdi | Foreign direct investment | The ratio of actual use of foreign capital to GDP | 0.006 | 0.000 | 0.095 | 2232 |

| gov | Government intervention | Proportion of local government fiscal expenditure to GDP | 0.143 | 0.040 | 1.485 | 2232 |

| cyjg | Industrial structure | The ratio of gross output of secondary industry to GDP | 0.507 | 0.161 | 0.859 | 2232 |

| rd | R&D expenditure | Ratio of scientific expenditure to local government fiscal expenditure | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 2232 |

| wage | Wage | The natural log of per capita wage | 3.086 | 0.720 | 7.775 | 2232 |

| mal | Gender | The municipal party secretary is 1 for men, and 0 for female | 0.960 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 2232 |

| age | Age | Municipal Party Secretary’s age | 52.497 | 39.000 | 61.000 | 2203 |

| maj | Professional background | The secretary of the municipal party committee majoring in science and engineering takes 1, otherwise 0 | 0.186 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 2232 |

| xl | Education | The secretary of the municipal party committee having a doctorate takes 1, otherwise is 0. | 0.189 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 2232 |

| gtech | Green technological progress | Green patent output per 100 R&D personnel | 0.401 | 0.000 | 16.050 | 2232 |

| tec | Technical progress | Patent output per 100 R&D personnel | 3.748 | 0.693 | 10.309 | 2232 |

Instrumental variables

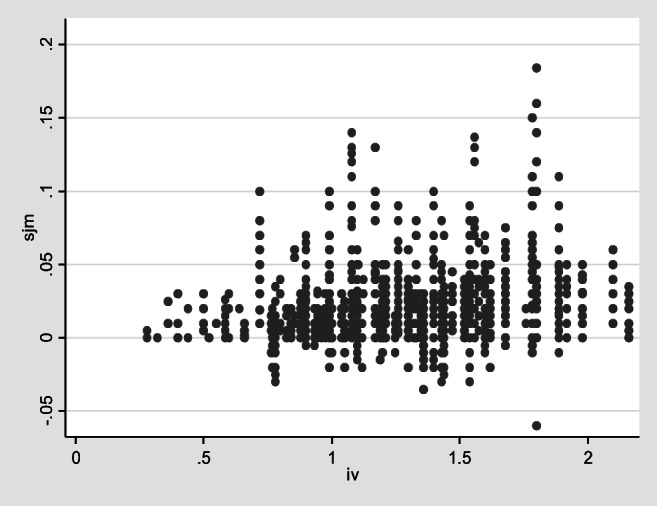

There may be an endogenous problem between economic growth expectation and air pollution. Economic development often directly causes air pollution, but air pollution will reversely reduce the economic expectation of local governments. Although the potential variables affecting air pollution have been controlled in this paper, the possible missing variables cannot be completely solved. Therefore, it is an effective way to accurately assess the relationship between economic growth expectations and air pollution to find appropriate instrumental variables to minimize the possible endogenous problem of indicator selection. Generally speaking, in the political system of people’s congress, there is a top-down appointment of officials and a pyramidal hierarchy. The economic tournament system makes each prefecture-level city government set the annual economic growth target, and different cities often have the competitive relationship at the same level. Local officials often set higher economic growth expectations than those of cities at the same level in the province in order to gain a higher initiative in political promotion (Yu et al. 2016). For prefecture-level city administrators, political promotion in each province is limited. If the larger number of prefecture-level cities in a province, the relatively higher the chiefs of prefecture-level cities are likely to set annual economic growth expectations (Liu et al. 2019). It is worth mentioned that the determination of the administrative level of prefecture-level cities depends on the central government, and the number of cities at the prefecture-level basically remained the same from 2003 to 2015, satisfying the exogenous condition of the selection of instrumental variables. However, the problem is that the regional fixed effect of the panel data model will be ineffective if only the number of prefecture-level cities in the province is used as the instrumental variable. Therefore, this paper selects the interaction term between the number of prefecture-level cities and the expected economic growth of the province in the next year as the instrumental variable of the expected economic growth of prefecture-level cities. In terms of the time relationship, the economic growth forecast of provincial governments in the next year will not affect the economic growth forecast of prefecture-level cities this year. Figure 1 and Fig. 2 are scatter plots of the relationship between instrumental variables and the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level municipal governments and the government’s “overweight” of economic growth expectations, showing a positive statistical relationship between instrumental variables and economic growth expectations.

Fig. 1.

Instrument variable IV and the government’s economic expectations

Fig. 2.

Instrument variable IV and the “increment” of economic expectations

Data source description

The economic growth forecasts of local governments come from the annual work reports of provincial and prefecture-level municipal governments. The economic data at the city level are from China urban statistical yearbook and China regional statistical yearbook. The personal information of party secretaries of local governments is from the Wind database. Data of urban green patent come from patent database of national intellectual property office. The PM2.5 data of haze pollution is the global PM2.5 satellite raster data released by Columbia University, and the data is further decoded by ARCGIS technology, and then point-to-point matching is conducted according to sample data on the longitude, latitude, and climate of each city, and the average PM2.5 concentration data of each city is finally obtained.

The effect of the government’s economic growth expectations on air pollution

This section examines the impact of economic growth expectations of prefecture-level municipal governments on air pollution, as shown in Table 3. The results indicate that the regression coefficient between the economic growth expectations and regional SO2 emissions is positive, and is significant at least at 10%. This indicates that the higher the local government’s economic growth expectations, the greater the regional SO2 emissions and the worse the air pollution. However, the regression coefficient between the economic growth expectations and PM2.5 concentration is negative and not significant. When using different measures of air pollution, the relationship between government economic growth expectations and air pollution is not robust. This may be related to the inherent endogenous nature of the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level municipal governments. Considering the potential endogenous problems between the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities and regional air pollution, we display the regression results of instrumental variables in columns (5)–(8). The results indicate that the values of the Cragg-Donald Wald F statistic for the weak instrument variable test are 165.612, 159.969, 175.307, and 159.969, which are much larger than the critical value of 16.38, indicating that there is not a problem of weak instrument variable selection. According to the regression results of the first stage, there is a significant positive relationship between the instrumental variables and the government’s economic growth expectations and the “overweight” in economic growth expectations. Consistent with the previous theoretical expectations, the number of prefecture-level cities in a province has significantly increased government economic growth expectations. It is observed in instrumental variables regression that the coefficient between economic growth expectations of the governments of prefecture-level cities and SO2 emissions and PM2.5 are significantly positive. Specifically, from the regression results of columns (6) and (8), it shows 1 unit increase in the local government economic growth expectations, the SO2 emissions will increase by 5.633%, and the PM2.5 concentration will increase by 0.761%. It can be seen that, after considering potential endogenous problem, the economic growth expectations significantly increase regional SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentrations causing deterioration of air quality.

Table 3.

The impact of government economic growth expectations on air pollution

| OLS regression results | Instrumental variable regression results (2sls) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| SO2 | SO2 | PM2.5 | PM2.5 | SO2 | SO2 | PM2.5 | PM2.5 | |

| exp | 1.201* | 1.205** | − 0.021 | − 0.020 | 4.710** | 5.633** | 0.669* | 0.761** |

| (0.615) | (0.608) | (0.100) | (0.100) | (2.265) | (2.267) | (0.375) | (0.380) | |

| gdp | − 0.282** | − 0.226* | 0.010 | 0.010 | − 0.365** | − 0.287* | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| (0.135) | (0.133) | (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.152) | (0.152) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| fdib | − 3.879 | − 7.087** | 1.644** | 1.591** | − 10.988** | − 13.168*** | 1.606** | 1.432** |

| (3.203) | (3.188) | (0.521) | (0.526) | (3.634) | (3.631) | (0.601) | (0.609) | |

| govb | 0.227 | 0.251 | − 0.021 | − 0.028 | − 0.006 | 0.054 | − 0.048 | − 0.048 |

| (0.279) | (0.274) | (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.293) | (0.288) | (0.049) | (0.048) | |

| cyjg | 1.752*** | 1.533*** | 0.050 | 0.048 | 1.166** | 0.752 | 0.001 | − 0.010 |

| (0.365) | (0.360) | (0.059) | (0.059) | (0.468) | (0.465) | (0.077) | (0.078) | |

| rd | − 14.548** | − 12.986** | 1.715** | 1.436* | − 14.769** | − 10.433 | 3.997*** | 3.619** |

| (4.914) | (4.890) | (0.799) | (0.807) | (6.514) | (6.590) | (1.078) | (1.106) | |

| wage | − 0.072 | − 0.066 | 0.000 | 0.000 | − 0.091* | − 0.083* | 0.004 | 0.005 |

| (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.048) | (0.047) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| mal | 0.004 | − 0.004 | − 0.034 | − 0.007 | ||||

| (0.064) | (0.011) | (0.067) | (0.011) | |||||

| age | 0.008** | − 0.000 | 0.006 | − 0.000 | ||||

| (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.004) | (0.001) | |||||

| maj | − 0.010 | − 0.001 | − 0.028 | 0.000 | ||||

| (0.034) | (0.006) | (0.036) | (0.006) | |||||

| xl | − 0.010 | − 0.001 | − 0.030 | − 0.003 | ||||

| (0.036) | (0.006) | (0.038) | (0.006) | |||||

| _cons | 15.969*** | 14.746*** | 3.672*** | 3.719*** | 17.280*** | 15.772*** | 3.673*** | 3.693*** |

| (2.134) | (2.118) | (0.347) | (0.350) | (2.383) | (2.390) | (0.394) | (0.401) | |

| The first stage regression results | ||||||||

| exp | exp | exp | exp | |||||

| 0.045*** | 0.046*** | 0.045*** | 0.046*** | |||||

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |||||

| Cragg-Donald Wald F | 165.612 | 159.969 | 175.307 | 159.969 | ||||

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2232 | 2203 | 2232 | 2203 | 1996 | 1969 | 1996 | 1969 |

| R-sq | 0.818 | 0.818 | 0.974 | 0.975 | 0.823 | 0.820 | 0.975 | 0.974 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

According to the descriptive statistical results in Table 2, it can be found that the “increment” between provincial and municipal economic growth expectations is as high as 0.023 indicating that the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities are generally higher than the economic growth expectations of the province. Due to the existence of administrative grading, local government officials may “increment” the government’s economic growth expectations due to potential promotion goals. Table 4 further presents the effect of increased local government economic growth expectations on air pollution. Similar to the endogenous treatment in Table 3, in column (3), it is observed that the regression coefficient between the local government’s growth expectations for economic growth and the SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentration is significantly positive. This indicates that the greater the government’s increment of economic growth expectations, the less conducive to air pollution control. One unit increase in economic growth expectations of the prefecture-level city exceeding that of its province, the city’s sulfur dioxide emissions and PM2.5 concentration will increase by 22.334% and 3.018%, respectively. Comparing the regression coefficients of economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities and air pollution in Table 3, it can be found that the increment of economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities has a greater effect on the deterioration of air pollution than the impact of economic growth expectations of single prefecture-level cities on air pollution.

Table 4.

The impact of increment of government economic growth expectations on air pollution

| OLS regression results | Instrumental variable regression results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | |

| sjm | 1.116 | − 0.089 | 22.334** | 3.018* |

| (0.694) | (0.115) | (10.772) | (1.724) | |

| gdp | − 0.218 | 0.009 | − 0.306* | 0.003 |

| (0.133) | (0.022) | (0.184) | (0.029) | |

| fdib | − 6.907** | 1.600** | − 15.537*** | 1.112 |

| (3.186) | (0.525) | (4.716) | (0.755) | |

| govb | 0.273 | − 0.026 | − 0.210 | − 0.084 |

| (0.274) | (0.045) | (0.400) | (0.064) | |

| cyjg | 1.587*** | 0.052 | − 0.195 | − 0.138 |

| (0.357) | (0.059) | (0.892) | (0.143) | |

| rd | − 13.162** | 1.440* | − 7.200 | 4.056** |

| (4.891) | (0.807) | (8.342) | (1.335) | |

| wage | − 0.063 | − 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.021 |

| (0.045) | (0.007) | (0.087) | (0.014) | |

| mal | 0.004 | − 0.004 | − 0.040 | − 0.008 |

| (0.064) | (0.011) | (0.080) | (0.013) | |

| age | 0.008** | − 0.000 | 0.005 | − 0.001 |

| (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.005) | (0.001) | |

| maj | − 0.009 | − 0.001 | − 0.034 | − 0.001 |

| (0.034) | (0.006) | (0.044) | (0.007) | |

| xl | − 0.010 | − 0.001 | − 0.081 | − 0.010 |

| (0.036) | (0.006) | (0.056) | (0.009) | |

| _cons | 14.690*** | 3.720*** | 16.610*** | 3.806*** |

| (2.119) | (0.349) | (2.938) | (0.470) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2203 | 2203 | 1969 | 1969 |

| R-sq | 0.817 | 0.974 | 0.750 | 0.967 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

Heterogeneity effect

Local governments often set annual economic growth expectations at the beginning of each year. The economic growth expectations will affect the development process of regional annual economic growth and the final achievement status (Liu et al. 2019). Based on economic growth expectations and real economic growth, local governments can achieve the goal of dynamically controlling or adjusting real economic growth. However, local economic growth is constrained by its factor resource endowment. Due to differences in factors such as location, resource endowment, and institutional environment, there is an unbalanced development trend in economic growth among cities. The economic development of China’s eastern coastal cities has reached the stage of middle-income, and its economic growth has begun to shift from extensive resource dependence to intensive high-quality direction, and the rate of intensive economic growth has gradually slowed. While the economic development level of cities in central and western China is low, they still rely on extensive economic growth mode, and the economic growth rate and quality of different cities are constantly diverging. Considering the differences in the stages of regional economic growth, this paper takes the average value of 16.08443 (natural logarithm) of economic output in each region as the threshold to divide China’s prefecture-level cities into two categories: economically developed cities and economically backward cities. Based on this, we analyze the differential impact of economic growth expectations on air pollution in cities with different economic development levels. The results are shown in Table 5. One hundred fourteen cities including Nanjing, Hangzhou, Wuhan, and Changsha are economically developed cities, and 151 cities including Yangquan, Tieling, Xining, and Yinchuan are economically backward cities. Considering the sensitivity of the mean value to the extreme value of the sample simultaneously, this section selects the 50% quantile of the economic output of each region, which is 15.93764 (natural logarithm value), as the threshold to group the economically developed cities and the economically backward cities. The number of economically developed cities increased from 114 to 133, while the number of economically backward cities decreased from 151 to 132. It was found that in economically backward cities, the economic growth expectations of local governments significantly increased SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentrations, so the city’s air pollution increased. To be specific, by grouping economically developed cities and backward cities with the mean of urban economic output as the threshold, we find that in economically backward areas, for every additional unit of economic growth expected, SO2 emissions will increase by 9.787% and PM2.5 concentration will increase by 1.646%. When we group economically developed cities and backward cities with the median of urban economic output as the threshold, we find that in economically backward areas, for each additional unit of economic growth expected, SO2 emissions will increase by 14.938% and PM2.5 concentration will increase by 2.193%. On the contrary, for developed cities, the government’s economic growth expectations do not have a significant impact on SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentrations.

Table 5.

Heterogeneity of economic growth expectations of different cities

| Take the mean as the threshold | Take the median as the threshold | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economically developed city | Economically backward cities | Economically developed city | Economically backward cities | |||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | |

| exp | 0.237 | 0.212 | 9.787** | 1.646** | − 2.557 | 0.021 | 14.938*** | 2.193*** |

| (2.670) | (0.503) | (4.280) | (0.706) | (2.927) | (0.504) | (4.416) | (0.735) | |

| gdp | − 0.406** | − 0.002 | − 0.292 | − 0.027 | − 0.448** | 0.031 | − 0.295 | − 0.089* |

| (0.183) | (0.035) | (0.272) | (0.045) | (0.184) | (0.032) | (0.312) | (0.052) | |

| fdib | 0.444 | 0.786 | − 25.306*** | 2.608*** | 1.489 | 1.169 | − 26.378*** | 2.378** |

| (4.822) | (0.908) | (5.434) | (0.896) | (4.886) | (0.842) | (5.881) | (0.978) | |

| govb | 0.080 | 0.018 | − 0.397 | − 0.230** | 0.161 | 0.018 | − 0.811 | − 0.346*** |

| (0.286) | (0.054) | (0.657) | (0.108) | (0.305) | (0.053) | (0.756) | (0.126) | |

| cyjg | 3.675*** | 0.248* | − 1.057* | − 0.092 | 3.511*** | 0.039 | − 1.665** | − 0.036 |

| (0.704) | (0.133) | (0.638) | (0.105) | (0.708) | (0.122) | (0.684) | (0.114) | |

| rd | 17.227 | 2.473 | − 2.416 | 3.361** | − 1.734 | − 0.017 | 2.400 | 5.438*** |

| (11.582) | (2.181) | (10.257) | (1.692) | (10.842) | (1.868) | (10.880) | (1.810) | |

| wage | − 0.134** | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.007 | − 0.148** | 0.000 | 0.071 | 0.009 |

| (0.059) | (0.011) | (0.075) | (0.012) | (0.062) | (0.011) | (0.081) | (0.014) | |

| mal | 0.056 | − 0.021 | − 0.062 | 0.003 | − 0.067 | − 0.014 | − 0.007 | 0.002 |

| (0.106) | (0.020) | (0.089) | (0.015) | (0.098) | (0.017) | (0.098) | (0.016) | |

| age | 0.002 | − 0.000 | 0.010* | − 0.001 | 0.012** | 0.000 | 0.001 | − 0.000 |

| (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.007) | (0.001) | |

| maj | 0.031 | 0.009 | − 0.086 | − 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.009 | − 0.047 | − 0.004 |

| (0.045) | (0.009) | (0.056) | (0.009) | (0.046) | (0.008) | (0.061) | (0.010) | |

| xl | − 0.074 | 0.002 | 0.054 | − 0.006 | − 0.049 | 0.003 | 0.042 | − 0.012 |

| (0.047) | (0.009) | (0.059) | (0.010) | (0.048) | (0.008) | (0.066) | (0.011) | |

| _cons | 16.724*** | 3.751*** | 14.403*** | 3.823*** | 17.588*** | 3.345*** | 14.546*** | 4.655*** |

| (2.859) | (0.538) | (3.920) | (0.647) | (2.886) | (0.497) | (4.456) | (0.741) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 881 | 881 | 1088 | 1088 | 1083 | 1083 | 886 | 886 |

| R-sq | 0.759 | 0.977 | 0.808 | 0.968 | 0.746 | 0.975 | 0.823 | 0.969 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

At different stages of development or facing different air pollution pressures, local governments may have different demands on economic growth expectations, or they may formulate economic growth expectations in different forms of constraints. Consequently, heterogeneous economic growth expectations have different impacts on air pollution. This paper makes the specific economic growth expectations made by local government, such as Shijiazhuang’s GDP in 2015 will increase by 8%, as the government’s deterministic economic growth expectations. When the words “above,” “more than,” “beyond,” “over” are used to describe economic growth expectations, such as “Shijiazhuang’s GDP will increase by more than 10% in 2013,” it is defined as the government’s rigid-constraint economic growth expectations. When the terms “about” and “between” are used, such as “Shijiazhuang’s GDP in 2016 will increase by about 7.5%,” it is defined as soft-constraint economic growth expectations. Table 6 presents the regression results between government economic growth expectations and SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentrations under different types of economic growth expectations. The results indicate that in cities with deterministic economic growth expectations and soft-constraint economic growth expectations, the regression coefficient between government economic growth expectations and regional SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentrations is not significant. When the government makes Rigid-constraint economic growth expectations, the regression coefficient between the government’s economic growth expectations and SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentration is positive, and it is significant at least at the level of 5%, which indicates that the rigid-constraint government’s economic growth expectations will significantly increase air pollution.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity of certainty and soft -constraint or rigid-constraint growth expectations

| Deterministic expectations | Rigid-constraint expectations | Soft-constraint expectations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | |

| exp | − 2.352 | 0.634 | 36.139*** | 2.881** | 11.367 | 10.120 |

| (2.724) | (0.484) | (9.568) | (1.325) | (44.179) | (9.726) | |

| gdp | − 0.405** | 0.051 | − 1.253* | − 0.286** | − 0.132 | − 0.773 |

| (0.178) | (0.032) | (0.655) | (0.091) | (3.518) | (0.775) | |

| fdib | − 9.180** | 1.407* | − 52.211** | − 4.391 | − 37.971 | 6.165 |

| (4.161) | (0.739) | (19.863) | (2.750) | (25.592) | (5.634) | |

| govb | 0.141 | − 0.023 | − 0.132 | − 0.272 | 6.931 | − 1.139 |

| (0.290) | (0.052) | (1.589) | (0.220) | (7.951) | (1.750) | |

| cyjg | 1.374** | − 0.113 | − 1.128 | 0.388 | 6.148* | 0.945 |

| (0.589) | (0.105) | (1.770) | (0.245) | (3.288) | (0.724) | |

| rd | − 10.661 | 2.861** | − 11.050 | 9.083** | − 3.019 | 19.133 |

| (7.587) | (1.347) | (22.767) | (3.152) | (61.825) | (13.610) | |

| wage | − 0.092 | − 0.006 | 0.468** | 0.052* | − 0.430 | − 0.018 |

| (0.057) | (0.010) | (0.203) | (0.028) | (0.312) | (0.069) | |

| mal | − 0.078 | − 0.015 | − 0.230 | − 0.011 | 0.156 | 0.134 |

| (0.083) | (0.015) | (0.234) | (0.032) | (0.699) | (0.154) | |

| age | 0.007 | 0.000 | 0.006 | − 0.002 | − 0.001 | − 0.004 |

| (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.013) | (0.002) | (0.030) | (0.007) | |

| maj | 0.053 | − 0.000 | − 0.197 | 0.014 | 0.142 | − 0.025 |

| (0.045) | (0.008) | (0.122) | (0.017) | (0.260) | (0.057) | |

| xl | 0.012 | − 0.009 | − 0.338** | 0.003 | − 0.159 | − 0.055 |

| (0.046) | (0.008) | (0.147) | (0.020) | (0.322) | (0.071) | |

| _cons | 18.290*** | 2.914*** | 29.349** | 8.092*** | 9.776 | 15.062 |

| (2.825) | (0.502) | (10.193) | (1.411) | (53.159) | (11.703) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1311 | 1311 | 455 | 455 | 203 | 203 |

| R-sq | 0.844 | 0.975 | 0.818 | 0.982 | 0.904 | 0.975 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

The government’s economic growth expectations often represent its expectations of the local economic growth rate for the year, and whether it can be achieved or adjusted will also change dynamically. The real economic growth rate of a region in that year can effectively measure the achievement of economic growth expectations, and it can also represent the rationality or effectiveness of the government’s economic growth expectations. Whether the economic growth expectation is finished may have different effects on air pollution. Therefore, we classify the cities according to whether they achieve the economic growth expectations or not, and the corresponding estimated results are shown in Table 7. It is found that in cities where economic growth expectations are achieved, as regional economic growth expectations increase, regional SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentrations gradually increase. In cities that does not achieve economic growth expectations, the regression coefficients between economic expectations and SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentrations are not significant. Specifically, for cities whose economic growth expectations have been achieved, one unit increase in economic growth expectations, SO2 emissions will increase by 10.790%, and PM2.5 concentration will increase by 2.180%.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity effect of economic growth expectations

| Over-achieved city | Unfinished city | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| SO2 | PM2.5 | SO2 | PM2.5 | |

| exp | 10.790** | 2.180** | 1.202 | − 0.340 |

| (3.408) | (0.701) | (3.488) | (0.518) | |

| gdp | − 0.288* | − 0.004 | − 1.988*** | − 0.087 |

| (0.174) | (0.036) | (0.460) | (0.068) | |

| fdib | − 18.956*** | 0.234 | − 19.184** | 2.678** |

| (4.357) | (0.896) | (9.138) | (1.357) | |

| govb | − 0.036 | − 0.055 | − 0.215 | − 0.201 |

| (0.290) | (0.060) | (1.095) | (0.163) | |

| cyjg | − 0.270 | − 0.059 | 5.023*** | 0.281 |

| (0.563) | (0.116) | (1.186) | (0.176) | |

| rd | − 3.831 | 3.906** | − 92.159** | 1.241 |

| (6.299) | (1.295) | (38.921) | (5.780) | |

| wage | 0.022 | 0.018 | − 0.046 | 0.015 |

| (0.066) | (0.014) | (0.099) | (0.015) | |

| mal | 0.034 | − 0.018 | − 0.065 | 0.021 |

| (0.079) | (0.016) | (0.166) | (0.025) | |

| age | 0.002 | − 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.001 |

| (0.005) | (0.001) | (0.010) | (0.001) | |

| maj | − 0.063 | − 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.005 |

| (0.044) | (0.009) | (0.083) | (0.012) | |

| xl | − 0.080* | − 0.010 | 0.071 | 0.017 |

| (0.047) | (0.010) | (0.083) | (0.012) | |

| _cons | 15.713*** | 3.719*** | 42.882*** | 5.119*** |

| (2.741) | (0.564) | (7.152) | (1.062) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1319 | 1319 | 650 | 650 |

| R-sq | 0.878 | 0.974 | 0.833 | 0.981 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

The results based on whether the economic growth expectations of prefecture-level cities are achieved show that in the cities where the expectations are achieved, the regional economic growth expectations significantly increase air pollution, while in the cities where expectations are not achieved, the economic growth expectations do not play a significant role. A natural question is whether the higher the degree of overfulfilling the economic growth expectations, the greater the deterioration effect of economic growth expectation on air pollution. In addition, whether air pollution will change with the completion degree of economic growth expectations. In order to verify the above problems, this section further studies the effect of different overfulfilled degrees on air pollution in cities whose economic growth expectations are overfulfilled by setting thresholds of 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4% or more according to the overfulfilled degree. The results are observed in Table 8.

Table 8.

The heterogeneity effect of the completion of the government's economic growth expectations

| Over 1% | Over 2% | Over 3% | Over 4% | Over 1% | Over 2% | Over 3% | Over 4% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| SO2 | SO2 | SO2 | SO2 | PM2.5 | PM2.5 | PM2.5 | PM2.5 | |

| exp | 10.577** | 10.671** | 11.825** | 16.296** | 2.115** | 2.503** | 3.592** | 4.421** |

| (3.504) | (4.159) | (5.118) | (6.877) | (0.757) | (0.931) | (1.209) | (1.659) | |

| gdp | − 0.191 | − 0.096 | − 0.098 | 0.190 | − 0.007 | 0.003 | − 0.025 | − 0.024 |

| (0.184) | (0.187) | (0.203) | (0.223) | (0.040) | (0.042) | (0.048) | (0.054) | |

| fdib | − 14.998*** | − 14.437** | − 15.383** | − 15.062** | 0.159 | − 0.171 | − 1.131 | − 1.130 |

| (4.547) | (4.987) | (5.402) | (5.990) | (0.982) | (1.116) | (1.276) | (1.445) | |

| govb | − 0.042 | − 0.047 | − 0.012 | − 0.164 | − 0.074 | − 0.081 | − 0.089 | − 0.090 |

| (0.290) | (0.295) | (0.307) | (0.339) | (0.063) | (0.066) | (0.072) | (0.082) | |

| cyjg | − 0.744 | − 0.652 | − 0.656 | − 1.725* | − 0.029 | − 0.118 | − 0.189 | − 0.226 |

| (0.582) | (0.663) | (0.786) | (1.001) | (0.126) | (0.148) | (0.186) | (0.241) | |

| rd | − 4.234 | − 4.206 | − 0.795 | − 2.783 | 3.779** | 3.975** | 3.763** | 3.746** |

| (6.231) | (6.331) | (6.731) | (7.247) | (1.346) | (1.417) | (1.590) | (1.748) | |

| wage | 0.014 | − 0.010 | 0.076 | 0.105 | 0.015 | 0.014 | 0.029 | 0.054** |

| (0.068) | (0.071) | (0.090) | (0.114) | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.021) | (0.027) | |

| mal | 0.028 | − 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.044 | − 0.021 | − 0.022 | − 0.035 | − 0.033 |

| (0.083) | (0.092) | (0.105) | (0.117) | (0.018) | (0.020) | (0.025) | (0.028) | |

| age | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.004 | − 0.001 | − 0.000 | − 0.000 | − 0.001 | − 0.001 |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.002) | |

| maj | − 0.032 | − 0.026 | − 0.032 | − 0.019 | − 0.000 | − 0.003 | − 0.012 | − 0.016 |

| (0.045) | (0.047) | (0.052) | (0.059) | (0.010) | (0.010) | (0.012) | (0.014) | |

| xl | − 0.042 | − 0.051 | − 0.071 | − 0.081 | − 0.004 | − 0.009 | − 0.005 | − 0.003 |

| (0.048) | (0.051) | (0.057) | (0.065) | (0.010) | (0.011) | (0.014) | (0.016) | |

| _cons | 14.412*** | 12.821*** | 12.490*** | 7.993** | 3.741*** | 3.581*** | 3.971*** | 3.883*** |

| (2.885) | (2.946) | (3.207) | (3.575) | (0.623) | (0.659) | (0.758) | (0.862) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1196 | 1099 | 979 | 872 | 1196 | 1099 | 979 | 872 |

| R-sq | 0.882 | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.883 | 0.975 | 0.974 | 0.970 | 0.967 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

Table 8 shows that the regression coefficient between economic growth expectations and SO2 emissions or PM2.5 concentration is significantly positive in cities with different overfulfilled levels of government economic growth expectation. And with the increase in the completion degree of urban economic growth expectations, the effect of economic growth expectations on SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentration gradually increases. When the completion degree of government’s economic growth expectations are over 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4%, respectively, for each additional unit increase in the government’s economic growth expectations, SO2 emissions in the area will increase by 10.577%, 10.671%, 11.825%, and 16.296%, correspondingly, the PM2.5 concentration increases 2.115%, 2.503%, 3.592%, and 4.421%. In general, the higher the degree to which the economic growth expectations are overfulfilled, the greater the deterioration effect of air pollution, the less conducive to improving environmental quality.

The technology progress effect of economic growth expectations on air pollution

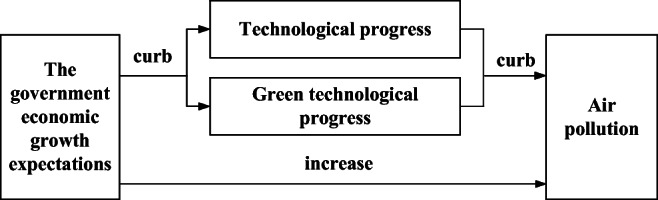

Technological progress, especially green technological progress, can effectively reduce the intensity of pollution emissions (Acemoglu et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2019), and it is also an important means to alleviate air pollution and improve environmental quality (Huang et al. 2020; Bai et al. 2020). However, green technology innovation generally has a “Curse to the Late Comer.” If an enterprise invests many resources in the R&D of green technologies in the early stage, it may squeeze out conventional technology input, resulting in reducing economic output or even inhibiting economic growth in an environment where conventional technology dominates. Compared with environmental performance, the current economic growth performance is still the main indicator of the promotion and evaluation of officials (Liu et al. 2019). Therefore, in order to attract the attention of higher-level governments and release powerful “capability signals,” local officials tend to set higher annual economic growth expectations to accelerate regional economic growth (Yu and Pan 2019). But it also exacerbated the speed of environmental degradation. Moreover, the economic priority development goal set by the government often leads to the imbalance of local fiscal expenditure, such as excessive investment in infrastructure, which squeezes out the financial investment in science and education (Fu and Zhang 2007; Yu and Pan 2019), which will further hinder regional technological progress. As shown in Fig. 3, on the one hand, in the process of achieving the expected economic growth targets of local governments, economic output will directly increase regional pollution emissions. On the other hand, in the process of achieving the expected goal of economic growth, resources are concentrated in the economic output advantage factors, squeezing out R&D resources (Liu et al. 2019), which is not conducive to technological innovation, especially green technological innovation, and thus increases pollution emissions.

Fig. 3.

The influence mechanism of government economic growth expectations on air pollution

Will the government’s economic growth expectations curb technological progress, especially green technological innovation, and further deteriorate air quality? In order to examine the effect of technological progress, this paper constructs the following model (2) to measure the effect of economic growth expectations on technological progress:

| 2 |

where the technologyit represents the technological level or green technological progress for city i of year t. We use the amount of patent and green patent granted in every 100 R&D to characterize. α measures the effect of the urban economic growth expectation on technological level or green technological progress. The remaining indexes in model (2) are the same as those in model (1). The specific regression results are observed in Table 9. The OLS regression results in Table 9 indicate that the regression coefficient between local government economic growth expectations and green technological progress or technological progress is negative and is significant at the level of 5%. This demonstrates that the greater the local government’s annual economic growth expectations, the less conducive to technological innovation. The regression results of the instrumental variables considering the endogenous economic growth expectations show that economic growth expectations significantly inhibit green technological progress, but the inhibitory effect on technological progress is not significant. Taking the regression results in column (5) as an example, one unit increase in local economic growth expectations, regional green patents will decrease by 0.956 units, indicating that the higher the annual economic growth expectations in a city, the lower the city’s green technology level.

Table 9.

The effect of technological progress on government economic growth expectations

| OLS regression results | Instrumental variable regression results | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| gtech | gtech | tec | gtech | gtech | tec | |

| exp | − 0.256** | − 0.248** | − 0.142** | − 0.912** | − 0.956** | − 0.546** |

| (0.0790) | (0.0801) | (0.070) | (0.310) | (0.318) | (0.260) | |

| gdp | − 0.336* | − 0.312* | − 0.242 | − 0.196 | − 0.145 | − 0.098 |

| (0.173) | (0.176) | (0.153) | (0.208) | (0.213) | (0.174) | |

| fdib | − 9.515** | − 9.628** | − 4.754 | − 8.101 | − 6.989 | − 8.646** |

| (4.115) | (4.201) | (3.646) | (4.983) | (5.097) | (4.164) | |

| govb | − 0.966** | − 0.943** | − 0.127 | − 0.676* | − 0.619 | 0.058 |

| (0.358) | (0.361) | (0.314) | (0.402) | (0.405) | (0.331) | |

| cyjg | − 2.796*** | − 2.867*** | 0.750* | − 2.405*** | − 2.411*** | 1.395*** |

| (0.469) | (0.474) | (0.412) | (0.641) | (0.653) | (0.534) | |

| rd | 23.147*** | 24.367*** | 33.072*** | 32.601*** | 33.488*** | 40.252*** |

| (6.312) | (6.443) | (5.593) | (8.931) | (9.250) | (7.557) | |

| wage | 0.470*** | 0.492*** | 0.016 | 0.462*** | 0.474*** | − 0.030 |

| (0.058) | (0.059) | (0.051) | (0.065) | (0.067) | (0.054) | |

| mal | − 0.109 | 0.031 | − 0.112 | 0.049 | ||

| (0.085) | (0.074) | (0.094) | (0.077) | |||

| age | 0.000 | 0.003 | − 0.000 | 0.002 | ||

| (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |||

| maj | 0.127** | 0.164*** | 0.161** | 0.174*** | ||

| (0.045) | (0.039) | (0.051) | (0.042) | |||

| xl | − 0.119** | − 0.078* | − 0.094* | − 0.059 | ||

| (0.047) | (0.041) | (0.054) | (0.044) | |||

| _cons | 5.975** | 5.622** | 6.547*** | 4.070 | 3.320 | 4.357 |

| (2.742) | (2.791) | (2.423) | (3.267) | (3.354) | (2.740) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 2232 | 2203 | 2203 | 1996 | 1969 | 1969 |

| R-sq | 0.676 | 0.679 | 0.938 | 0.685 | 0.686 | 0.940 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

It has become a consensus that technology upgrading, especially the progress of green technology, can effectively solve environmental problems (Acemoglu et al. 2012). As mentioned above, local government’s economic growth expectations deteriorate air quality, and the effect of their role is related to the extent to which the government’s economic growth expectations or expectations are fulfilled. Will the government’s economic growth expectations indirectly achieve the goal of curbing air pollution through technological innovation, especially green technology incentives? To this end, this paper controls the role of the government’s economic growth expectations, and tests the air pollution control effect of technological progress and green technological progress. The econometric model is as follows:

| 3 |

where θ is the partial effect parameter of technological progress and green technological progress on air pollution; γ is the effect of economic growth expectations on air pollution after the introduction of technical variables; the other parameters are the same as the regression model (1). According to the mediation effect definition, if ρ in model (1), α in model (2) and θ in model (3) are all significant, and γ in model (3) is less than ρ in model (1) or the significant degree decreases, then the mediation effect is proved to exist. The specific regression results are observed in Table 10.

Table 10.

Mediation effect of technological progress

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 | SO2 | PM2.5 | PM2.5 | |

| exp | 5.274** | 5.449** | 0.712* | 0.734* |

| (2.302) | (2.282) | (0.387) | (0.383) | |

| gtech | − 0.376** | − 0.052* | ||

| (0.018) | (0.003) | |||

| tech | − 0.034 | − 0.005 | ||

| (0.022) | (0.004) | |||

| gdp | − 0.293* | − 0.291* | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| (0.151) | (0.152) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| fdib | − 13.431*** | − 13.459*** | 1.396** | 1.389** |

| (3.617) | (3.626) | (0.607) | (0.609) | |

| govb | 0.031 | 0.056 | − 0.052 | − 0.048 |

| (0.287) | (0.288) | (0.048) | (0.048) | |

| cyjg | 0.662 | 0.799* | − 0.023 | − 0.003 |

| (0.461) | (0.468) | (0.077) | (0.078) | |

| rd | − 9.174 | − 9.077 | 3.793*** | 3.819*** |

| (6.574) | (6.616) | (1.104) | (1.110) | |

| wage | − 0.065 | − 0.084* | 0.007 | 0.005 |

| (0.048) | (0.047) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| mal | − 0.039 | − 0.033 | − 0.007 | − 0.006 |

| (0.067) | (0.067) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| age | 0.006 | 0.006 | − 0.000 | − 0.000 |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| maj | − 0.022 | − 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| (0.036) | (0.037) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| xl | − 0.033 | − 0.032 | − 0.003 | − 0.003 |

| (0.038) | (0.038) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| _cons | 15.897*** | 15.919*** | 3.710*** | 3.715*** |

| (2.382) | (2.387) | (0.400) | (0.401) | |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Regional effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1969 | 1969 | 1969 | 1969 |

| R-sq | 0.821 | 0.821 | 0.975 | 0.821 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses, and ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

The results show that, in columns (1) and (3), the government’s economic expectation exp significantly increases air pollution and the green technology progress gtech significantly inhibits air pollution. Combined with the regression results of model (1) and model (2), the green technological progress meets the mediating effect condition, indicating that the government’s economic growth expectations delays the change of green technological progress direction and aggravate air pollution. In columns (2) and (4), the government's economic growth expectations exp significantly increased air pollution, but the inhibition effect of technological progress tech on air pollution was not significant, which was not consistent with the regression results of mediating effect.

To further describe the respective contributions of technological progress and green technological innovation, combining with the ideas of Gelbach (2016), the mechanism contribution of technological progress and the green technological progress was decomposed. The contribution of green technological progress was equal to θ × α/ρ, where ρ corresponds to the regression coefficient of economic growth expectation exp in model (1), α corresponds to the regression coefficient of economic growth expectation exp in model (2), and θ corresponds to the regression coefficient of technology in model (3). However, the above regression results indicate that in the short term, technological progress has not reduced SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentration in a region, which does not meet the regression results of mediating effect. Therefore, in Table 11, it is observed that the explanatory contribution of green technology progress to SO2 emissions and PM2.5 concentration. The results demonstrate that the green technology progress can explain 6.38% of the SO2 emission effect and 6.53% of the PM2.5 effect caused by the government’s economic expectation respectively.

Table 11.

Decomposition of contributions to green technological progress

| Conduction mechanism | θi | αi | ρi | Contribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SO2 | Green technology (gtech) | − 0.376*** | − 0.956** | 5.633** | 6.38% |

| Technical progress (tec) | − 0.034 | − 5.459** | 5.633** | / | |

| PM25 | Green technology (gtech) | − 0.052* | − 0.956** | 0.761** | 6.53% |

| Technical progress (tec) | − 0.005 | − 5.459** | 0.761** | / |

Note: ***, **, and * indicate significant at the levels of 1%, 5%, and 10%, respectively

Conclusions

Combining the panel data of China’s prefecture-level cities from 2004 to 2015, and through dual-fixed model of panel data and the two-stage regression method of instrumental variables, this paper examines whether local government economic growth expectations will affect air pollution. We also analyzed the differential impact of expectations of different properties and different degrees of completion on air pollution, finally examines the contribution of technological innovation. The main results are as follows: (1) The annual economic growth expectations of various prefecture-level municipal governments in China significantly increase air pollution. After controlling for possible endogenous problems in the setting of economic growth expectations, the regression results of instrumental variables are still significant. Moreover, the “increment” behavior of economic growth expectations between prefecture-level cities and the province will further aggravate air pollution. (2) The relationship between the government’s economic growth expectations and the air pollution is significantly differentiated due to the level of urban economic development, the certainty of economic growth expectations, and the completion degrees of economic growth expectations. In backward regions, the city’s economic growth expectations have significantly increased air pollution, while in developed regions, the city’s economic growth expectations have not had a significant impact on air pollution. Deterministic and soft-constraint economic growth expectations have not increased regional air pollution, while regional rigid-constraint economic growth expectations have significantly increased regional pollution. (3) If a city overfulfills its economic growth expectations, it will increase the air pollution. For cities that does not achieve their economic growth expectations, the government’s economic growth expectations have no significant effect on air pollution. And the higher the city’s economic growth expectations are exceeded, the more serious the air pollution. Specifically, when the completion degree of government’s economic growth expectations are over 1%, 2%, 3%, and 4%, respectively, the city’s SO2 emissions increase by 10.577%, 10.671%, 11.825%, and 16.296%, respectively. The PM2.5 concentration increases by 2.115%, 2.503%, 3.592%, and 4.421% respectively. (4) Green technological progress is an effective way for cities’ economic growth expectations to affect air pollution. The government’s economic growth expectations will deteriorate air quality by curbing green technological progress, and its explanation contribution is about 6.5%.

The conclusion demonstrates that the economic growth expectations of local government will undoubtedly promote the economic development effectively, but it will also significantly increase the air pollution. In the context of increasing environmental pressure, how to incorporate environmental quality or green development into the performance evaluation of officials, establish a development evaluation index system including economic indicators and environmental indicators, and reduce local officials’ excessively high preset economic growth expectations for competitive purposes, seems particularly important. The first is that the central government should incorporate environmental development and green development capabilities and other sustainable development factors into the official assessment system by increasing green development–related indicators. Diversified performance evaluation standards of local officials can contribute to the high-quality development of the local economy. The second is to increase the flexibility of the central or provincial governments’ economic growth expectations. According to the regional resource endowment, the stage of economic development, the structure of the economy, and the environmental changes that may be caused excessive growth the economy, it is necessary to leave some floating space for the local government to set the economic expectation. This can avoid overly strict economic control, and the flexible economic growth expectations can guide local governments to effectively reduce air pollution and improve environmental quality. The third is that local governments should provide incentives for green technology innovations, optimize their economic behaviors based on the flexible development of economic growth expectations, regional economic growth potential, and the need for environment quality improvement. In this manner, local governments will provide a long-term incentive mechanism for enterprises’ green technology innovation, jointly control the air pollution and improve environmental quality.

Authors’ contributions

L. W., H.W., and Z.D. conceived and designed the experiments. L.W., S.W., and Z.C. performed the experiments. H.W. and Z.D. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The Major Projects of National Social Science Fund of China (20ZDA069); the National Natural Science Fund of China (71573088). And the funding for the research complied with the project management regulations.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Acemoglu D, Aghion P, Bursztyn L. The environment and directed technical change. Am Econ Rev. 2012;102:131–166. doi: 10.1257/aer.102.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adkin LE. Technology innovation as a response to climate change: the case of the climate change emissions management corporation of Alberta. Rev Policy Res. 2019;36:603–634. doi: 10.1111/ropr.12357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aghion P, Dechezlepretre A, Hemous D, Martin R. Carbon taxes, path dependency and directed technical change: evidence from the auto industry. J Polit Econ. 2016;124:1–51. doi: 10.1086/684581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Albrizio S, Kozluk T, Zipperer V. Environmental policies and productivity growth: evidence across industries and firms. J Environ Econ Manag. 2017;81:209–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2016.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai CA, Feng CB, Yan HC, Yi XA, Chen ZD, Wei WE. Will income inequality influence the abatement effect of renewable energy technological innovation on carbon dioxide emissions? J Environ Manag. 2020;264:110482. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman A, Kildegaard A. Clean technological change in developing country industrial clusters: Mexican leather tanning. Environ Econ Policy Stud. 2010;12:115–132. doi: 10.1007/s10018-010-0164-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buehn A, Farzanegan MR. Hold your breath: a new index of air pollution. Energy Econ. 2013;37:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2013.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai H, Chen Y, Gong Q. Polluting the neighbor: unintended consequences of China’s pollution reduction mandates. J Environ Econ Manag. 2016;76:86–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2015.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Duan Q. Decomposition analysis of factors driving CO2 emissions in Chinese provinces based on production-theoretical decomposition analysis. Nat Hazards. 2016;84:267–277. doi: 10.1007/s11069-016-2313-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Wang SJ, Zhou CS, Li M. Does the path of technological progress matter in mitigating China’s PM2.5 concentrations? Evidence from three urban agglomerations in China. Environ Pollut. 2019;254:113012. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel BL, Gokmenoglu KK, Taspinar N. An approach to the pollution haven and pollution halo hypotheses in MINT countries. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;26:23010–23026. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05446-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechezlepr A, Glachant M, Hascic I, Johnstone N, Meniere Y. Invention and transfer of climate change-mitigation technologies: a global analysis. Rev Environ Econ Policy. 2011;5:109–130. doi: 10.1093/reep/req023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitra K, Efthimios Z. The environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) Theory-Part A: concept, causes and the CO2 emissions case. Energy Policy. 2013;62:1392–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.07.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dong ZQ, He YD, Wang H. Dynamic effect retest of R&D subsidies policies of China’s auto-industry on directed technological change and environmental quality. J Clean Prod. 2019;231:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizi A, Guarini G, Meliciani V. Green patents, regulatory policies and research network policies[J] Research Policy. 2018;47:1018–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksson PG, List JA, Millimet DL. Bureaucratic corruption, environmental policy and inbound US FDI: theory and evidence. J Public Econ. 2003;7:1407–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(02)00016-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Zhang Y. Sinicism decentralization and fiscal expenditure structure bias: the cost of competition for growth. Manag World. 2007;03:4–12+22. [Google Scholar]

- Gao XX, Zheng HD, Zhang Y, Golsanami N. Tax policy, environmental concern and level of emission reduction. Sustainability. 2019;11:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gelbach JB. When do covariates matter? And which ones and how much. J Labor Econ. 2016;34:509–543. doi: 10.1086/683668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray WB, Shadbegian RJ. Plant vintage, technology and environment regulation. J Environ Econ Manag. 2003;46:384–402. doi: 10.1016/S0095-0696(03)00031-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto M. Environmental regulation and the productivity of Japanese manufacturing industries. Resour Energy Econ. 2006;28:299–312. doi: 10.1016/j.reseneeco.2005.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison A, Hyman B, Martin L, Nataraj S. When do firms go green? Comparing price incentives with command and control regulations in. Working Paper: India; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- He G, Wang S, Zhang B, 2018. Environmental regulation and firm productivity in China: estimates from a regression discontinuity design. Working Paper.

- Hou BQ, Wang B, Du MZ, Zhang N. Does the SO2emissions trading scheme encourage green total factor productivity? An empirical assessment on China’s cities. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;27:6375–6388. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-07273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Ren S, Wang Y, Chen X. Can carbon emission trading scheme achieve energy conservation and emission reduction? Evidence from the industrial sector in China. Energy Econ. 2020;85:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.eneco.2019.104590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JB, Chen X, Yu KZ, Cai XC. Effect of technological progress on carbon emissions: new evidence from a decomposition and spatiotemporal perspective in China. J Environ Manag. 2020;274:110953–110966. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Zhang S, 2015. Willingness to pay for clean air: evidence from air purifier markets in China. NBER Conference Paper.

- Landry PF, Lü X, Duan H. Does performance matter? Evaluating political selection along the Chinese administrative ladder. Comp Polit Stud. 2017;51:1074–1105. doi: 10.1177/0010414017730078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao A. Corruption and the environment Kuznets Curve: empirical evidence for sulfur. Ecol Econ. 2010;69:2191–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2010.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li HB, Zhou LA. Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ. 2005;89:1743–1762. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2004.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu C, Weng X, Zhou L. Target setting in tournaments: theory and evidence from China. Econ J. 2019;129:2888–2915. doi: 10.1093/ej/uez018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Wang B, Wu W, Qi S. The potential influence of the carbon market on clean technology innovation in China. Clim Pol. 2018;18:1–18. doi: 10.1080/14693062.2017.1392279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb M, Mobarak AM. Decentralization and pollution spillovers: evidence from the re-drawing of county borders in Brazil. Rev Econ Stud. 2017;84:464–502. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdw023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DY, Xu CF, Yu YZ, Rong KJ, Zhang JY. Economic growth target, distortion of public expenditure and business cycle in China. China Econ Rev. 2019;11:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Milani S. The impact of environmental policy stringency on industrial R&D conditional on pollution intensity and relocation costs. Environ Resour Econ. 2017;68:595–620. doi: 10.1007/s10640-016-0034-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pasten R, Figueroa E. The environmental Kuznets Curve: a survey of the theoretical literature. Int Rev Environ Resour Econ. 2012;6:195–224. doi: 10.1561/101.00000051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su FB, Tao R, Xi L, Li M. Local officials’ incentives and China’s economic growth: tournament thesis reexamined and alternative explanatory framework. China World Econ. 2012;20:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-124X.2012.01292.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Yuan X, Xu M. The public perceptions and willingness to pay: from the perspective of the smog crisis in China. J Clean Prod. 2016;20:1635–1644. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JS, Wei YH. Agglomeration, environmental policies and surfacewater quality in China: a study based on aquasi-natural experiment. Sustainability. 2019;11:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Deng Y, Huang J, Morck R, Yeung B, 2013. Incentives and outcomes: China’s environmental policy. NBER Working Pap.

- Xu XX, Liu YY. Economic growth target management. Econ Res J. 2017;7:18–33. [Google Scholar]