Abstract

Objectives

Drug checking as a tool for harm reduction is offered in certain cities throughout Europe, the USA, and Australia, but in general, it is internationally still scarcely available and controversially discussed. This study aimed at investigating the potential impact of a drug-checking offer on Berlin nightlife attendees' illicit drug use and at identifying the encouraging and discouraging factors for using or refraining from such an offer.

Methods

Using an online questionnaire, we conducted a cross-sectional survey in a Berlin party scene. A total of 719 people participated in the survey that took part in 2019.

Results

The vast majority of participants (92%) stated that they would use drug checking, if existent. If the test revealed the sample to contain a high amount of active ingredient, 91% indicated to take less of the substance than usual. Two-thirds (66%) would discharge the sample if it contained an unexpected/unwanted agent along with the intended substance. If the sample contained only unexpected/unwanted substances and not the intended substance at all, 93% stated to discharge the sample. Additional brief counseling was stated to be useful. Participants showed a comparatively high substance use.

Conclusions

Drug checking as a harm reduction tool was highly accepted in the scene, and the majority of participants stated to align their consumption behavior accordingly, in a reasonable manner. A concomitant consultation would be appreciated, which may be used to direct educational information about harms and risks to users.

Keywords: Drug checking, Substance use, Party scene, Prevention, Harm reduction

Introduction

Aside from potential long-term side effects of illicit drug use in the nightlife setting, mainly two aspects are discussed with respect to short-term risks and harm reduction: overdosing and contamination with other psychoactive substances or potentially harmful cutting agents [1, 2, 3].

To face the risks of unexpectedly large doses or unknowingly used adulterants, “drug checking” or “pill testing” has been established in several European countries since the early 1990s [4, 5]. Drug checking refers to a harm reduction tool which provides information about ingredients and doses of the samples submitted by nightlife attendees and is conducted either on-site at nightclubs and festivals or in stationary testing facilities [5]. Presentation of the analysis results is often accompanied by an individual feedback or a brief intervention [5]. In addition, the results are frequently posted online as an easy accessible source of information for users (e.g., pill reports), creating a worldwide network to share data (e.g., Trans-European Drug Information project), which can also be used for (inter)national warning campaigns preventing severe intoxications [5, 6, 7, 8].

Recent studies showed that the large majority of nightlife attendees would use drug checking if it was more widely available [6, 9, 10, 11]. In addition to most nightlife attendees believing that drug checking could contribute to harm reduction, several studies showed that it could in fact influence the user's consumption patterns: After having encountered unexpected substances, most users intended to use less of the sample or not at all [3, 6, 11, 12, 13, 14]. These findings do not only apply to the heterogenous group of nightlife attendees but also to heavy and addicted drug users, which is why drug checking might be used to face the fentanyl overdose epidemic in the USA [15, 16].

Critics of drug checking fear that it might encourage nightlife attendees to use (more) illicit drugs due to an unjustified feeling of safety: even if adulterants and unexpectedly high doses are minimalized, illicit drug use remains potentially harmful, as the intended substance itself is generally assumed to be the most harmful ingredient [9, 17, 18, 19].

Although the majority of Berlin nightlife attendees have recently been shown to use illicit drugs and rated drug checking as the most useful preventive measure, no drug-checking service could be established in Germany until date due to the interpretation of German narcotics regulation by political decision makers [20, 21]. A recent juridical evaluation by Nestler, however, confirmed the compatibility of a drug-checking offer with German narcotics regulation [22]. These findings provide the basis for a pilot project offering drug checking in Berlin: users will be able to anonymously submit their samples in one of three stationary facilities, where they will simultaneously get a (mandatory) consultation by prevention workers [23]. The results will be provided by an external laboratory within a few days and communicated by telephone, online, or in the course of a further consultation at the stationary facility [23]. The costs will be covered by the Berlin public health administration; an exact start date has not yet been set [23]. This study thus aimed at investigating reasons for using or not using drug checking and its potential impact on Berlin nightlife attendees' consumption patterns.

Methods

An online questionnaire was designed and distributed in a Berlin party scene. Data collection occurred from January 01 to March 11, 2019, after approval by the Ethical Review Committee of Charité − Universitätsmedizin Berlin (application no. EA4/157/17).

The questionnaire contained questions concerning demographic information, such as age, gender, and highest degree of education. The questionnaire also covered the 30-day, 1-year, and lifetime prevalence for legal and illegal substances. With regard to the way of substance acquisition ([un]familiar dealers/friends/online) and the questions concerning drug checking, symmetrical and balanced 5-point Likert items from 1 to 5 (1 = strong disagreement, 2 = disagreement, 3 = neutral, 4 = agreement, and 5 = strong agreement) were used (Fig. 1). Anticipated reactions to different results were rated by a nonsymmetrical, unbalanced scale (use more/less/the same amount/discharge the sample; Table 2). Results are reported as percentages for each answer.

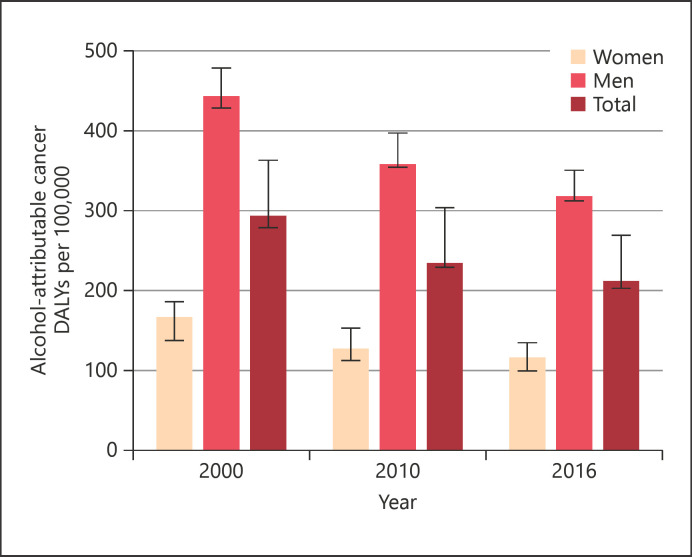

Fig. 1.

Encouraging and discouraging aspects for the use of drug checking. Distribution of answers ranging from total disagreement to total agreement is presented as percent.

Table 2.

Cross table of anticipated reaction to the test results, specified according to gender

| Variable | Total, n (%) | Take usual amount, n (valid %) | Take less, n (valid %) | Take more, n (valid %) | Discharge, n (valid %) | Other, n (valid %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction in case of high amount (χ2 [6] = 17.76, p = 0.01, φ = 0.11) | ||||||

| Total | 715 (100) | 33 (4.6) | 647 (90.5) | 0 | 18 (2.5) | 17 (2.4) |

| Female | 326 (45.6) | 12 (3.7) | 269 (90.8) | 0 | 15 (4.6) | 3 (0.9) |

| Male | 382 (53.4) | 21 (5.5) | 344 (90.1) | 0 | 3 (0.8) | 14 (3.7) |

| Other | 7 (0.9) | 0 | 7 (100) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing values | 4 (0.5) | |||||

| Reaction in case of contamination (χ2 [6] = 6.6, p = 0.37, φ = 0.06) | ||||||

| Total | 715 (100) | 9 (1.3) | 155 (21.7) | 0 | 472 (66) | 79 (11) |

| Female | 326 (45.6) | 5 (1.5) | 64 (19.6) | 0 | 222 (68.1) | 35 (10.7) |

| Male | 382 (53.4) | 4 (1.0) | 91 (23.8) | 0 | 245 (64.1) | 42 (11) |

| Other | 7 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) |

| Missing values | 4 (0.5) | |||||

| Reaction in case of only unexpected substances (χ2 [8] = 17.32, p = 0.04, φ = 0.10) | ||||||

| Total | 715 (100) | 4 (0.6) | 19 (2.7) | 1 (0.1) | 666 (93.1) | 25 (3.5) |

| Female | 326 (45.6) | 0 | 15 (4.6) | 0 | 301 (92.3) | 10 (3.1) |

| Male | 382 (53.4) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 1 (0.3) | 358 (93.7) | 15 (3.9) |

| Other | 7 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (100) | 0 |

| Missing values | 4 (0.5) | |||||

Most commonly stated reactions in the category “other” are given as follows, in descending order: In case of high amount, depending on the setting/substance (n = 4), consume according to your body weight (n = 3), start with small dose (n = 3). In case of an unexpected substance, depending on the risk potential of the unexpected substance detected (n = 44), obtain additional information on the unexpected substance detected (friends, online, etc.) (n = 39). In case of only unexpected substances, depending on the risk potential of the unexpected substance(s) detected (n = 14), obtain additional information on the unexpected substance(s) detected (friends, online, etc.) (n = 11).

The questionnaire was accessible via the platform SoSci Survey. The participants were directed toward the questionnaire by posting the invitation to the survey on social media platforms of included clubs (e.g., Facebook group of Club X) and scene-intern communication platforms which are not tied to a specific club (e.g., portals where parties are announced). (For inclusion criteria concerning the selected clubs, see Betzler et al. [20].)

Although it was aimed to depict a realistic sample of the Berlin nightlife scene by this algorithm, the sample does not claim representativity. The questionnaire was composed in German and English and tested for its acceptance and understandability prior to being deployed. All participants gave informed consent prior to online survey participation. (For details of data analysis and plausibility filter, see Betzler et al. [20].) The filter was additionally set at excluding cases with more than 20% missing values. In total, 150 participants were excluded. Missing values were handled by pairwise deletion. Only explorative analysis and descriptive statistics were applied.

In order to test the association between nominal demographic variables (gender, educational level, and psychiatric disorder) and nominal Likert items (anticipated reaction to test results), χ2 tests were used. Results are reported as Fisher's exact test as cell frequency was partially <5.

Correlations between age and encouraging/discouraging aspects and intention to use drug checking were calculated using nonparametric correlation analysis (Spearman). The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

In total, 719 questionnaires met the filter criteria and were included into data analysis.

Sociodemographic Data

In all, 45.6% (N = 326) of the participants stated their sex to be female, 53.4% (N = 382) to be male, and 1% (N = 7) specified it as “other.” The mean age of the participants was 30.3 years, ranging from 18 to 60 years. Concerning the highest degree of education, 53.3% (N = 383) of the participants reported to have a college degree, 26.4% (N = 190) to have obtained an upper secondary school degree (“Abitur,” A-level), 14.6% (N = 105) to have finished an apprenticeship, 4.2% (N = 30) to have an intermediate secondary school degree, 0.8% (N = 6) to have a lower secondary school degree, and one participant (0.1%) stated to have no degree. With regard to psychiatric disorders, 18.4% (N = 131) of the participants answered to have or have had a (diagnosed) psychiatric disorder, now and/or in the past.

Substance Use

The most prevalent illicit substances used were cannabis, amphetamine, 3,4-methyl-enedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA), cocaine, and ketamine. The 1-month, 1-year, and lifetime prevalence of substance use are visualized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Thirty-day, 1-year, and lifetime prevalence of participants

| Substance | Total, N | Thirty-day, % | One-year, % | Lifetime, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | 714 | 88.2 | 95.2 | 99.6 |

| Nicotine | 710 | 74.4 | 84.4 | 95.2 |

| Cannabis | 711 | 60.9 | 82.0 | 97.2 |

| Amphetamine (speed, fet, powder) | 709 | 53.3 | 81.7 | 92.9 |

| MDMA (ecstasy) | 711 | 47.1 | 84.0 | 94.4 |

| Cocaine | 709 | 41.5 | 73.5 | 89.3 |

| “K” | 701 | 36.7 | 62.2 | 78.2 |

| GHB/GBL (liquid ecstasy, “G”) | 690 | 10.9 | 16.1 | 32.9 |

| LSD (acid) | 689 | 9.9 | 38.1 | 59.7 |

| Benzodiazepines (e.g., Tavor, Valium) | 694 | 8.2 | 19.0 | 37.0 |

| Neuro-enhancer (e.g., methylphenidate, modafinil) | 692 | 4.5 | 10.0 | 32.2 |

| Poppers (e.g., amyl nitrite) | 691 | 4.3 | 14.5 | 39.8 |

| Psilocybin (magic mushrooms) | 696 | 3.9 | 29.0 | 67.4 |

| Synthetic cathinones | 692 | 3.8 | 7.8 | 17.8 |

| Opioid-based painkillers (e.g., tramal, tilidin) | 693 | 2.6 | 10.5 | 28.7 |

| Methamphetamine (crystal meth, ice) | 694 | 1.9 | 3.9 | 15.4 |

| RCs | 692 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 17.5 |

| Heroin | 693 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 4.6 |

| Synthetic cannabinoids | 687 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 19.2 |

| Othersa | 233 | 6.4 | 21.5 | 34.8 |

MDMA, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine; K, ketamine; GHB, gamma-hydroxybutyric acid; GBL, gamma-butyrolactone; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; RC, research chemical.

Ten most popular substances stated in this category are given as follows, in descending order: 2C-B (n = 40), (5-Meo-)DMT (n = 16), nitrous oxide (n = 7), kratom (n = 5), mescaline (n = 4), salvia (n = 4), ayahuasca (n = 3), 4-FA (n = 3), khat (n = 2), and methoxetamine (n = 2).

Substance Acquisition

When asked for the way of substance acquisition (“If you are planning to consume at an event, where do you purchase or get your substances?”), 77% of the participants stated to get their substances prior to attending an event (36.2% always and 40.8% mainly before the event); 19.7% stated partly before and partly at the event; and only 3.3% at the event (3.3% mainly and 0% always at the event). If substances were not purchased at the event, users mostly received them from familiar dealers (74.6% agree or strongly agree, hereafter clustered to just “agree,” and 13.5% disagree or strongly disagree, hereafter clustered to just “disagree”) or from friends (74.1% agree and only 7.3% disagree). Less often, users purchased their substances from unknown dealers (only 7.4% agree and 75.9% disagree) or by online order (7.7% agree and 86.4% disagree).

Encouraging and Discouraging Aspects concerning Drug Checking

Participants stated that avoiding contamination with cutting agents to be the most important motivator to use drug checking, whereas concerns regarding criminal prosecution were stated to be the most discouraging aspect. All encouraging and discouraging aspects for the use of drug checking are shown in Figure 1.

A positive correlation between age and the motivation to avoid overdoses could be found (rs = 0.08, p = 0.03) and a nonsignificant trend between age and the motivation to avoid unintended psychoactive substances (rs = 0.07, p = 0.09). Furthermore, a negative correlation was found between age and just curiosity toward ingredients (rs = −0.08, p = 0.04). No significant correlation was found between age and other motivations (contamination/testing the dealer/personal consultation).

Concerning discouraging aspects of drug checking, a positive correlation between age and concerns of anonymity/data privacy was found (rs = 0.09, p = 0.02). No significant correlation was found between age and other discouraging aspects (concerns of criminal prosecution/being recognized by others/too complicated/uselessness).

Willingness to Use a Drug-Checking Offer

Of all participants, 91.9% stated that they would use a drug-checking offer in general (67.7% total agreement and 24.4% agreement). It was neutrally stated by 6.3%, and only 1.5% stated not to use it (0.8% disagreement and 0.7% total disagreement). We found a nonsignificant trend of a negative correlation between willingness to use drug checking and age (rs = −0.07, p = 0.06).

Additional Counseling

Drug checking is usually accompanied by a consultation conducted by the drug-checking team including reflection on the user's consumption behavior. With regard to this consultation, participants mostly stated this to be useful (79.3% agree and only 5.6% disagree). The item “this may be useful for others, but not for myself” was stated neutral (33% neutral, 33.6% agree, and 33.4% disagree). The item “unnecessary” was rated with disagreement (5.8% agree and 79.1% disagree). The item “a reason not to make use of a drug-checking offer” was also rated with disagreement (8.9% agree and 79.1% disagree).

Anticipated Reaction to Drug-Checking Results

If the test revealed the sample to contain a high amount of active ingredient, 90.5% indicated to take less of the substance than usual. Two-thirds (66%) would discharge the sample if it contained an unexpected/unwanted agent in addition to the intended substance. If the sample contained only unexpected/unwanted substances and not the intended substance at all, 93.1% stated to discharge the sample. Significant associations between gender (but not level of education or psychiatric record) and the anticipated reaction to test results were found. Table 2 shows how users indicated to react to the test results, specified by gender.

Discussion

This study was the first to examine Berlin nightlife attendees' attitudes toward drug checking as a harm reduction tool in detail, given the fact that it has been shown to be the most favored preventive measure in this target group by a previous study, the SuPrA-Survey [20]. Almost all participants stated they would use drug checking if available. The majority of the participants indicated to use less when facing a high amount of active ingredient and to discharge the sample in case only unexpected substances were detected. In contrast to previously conducted studies, most participants also indicated to discharge samples containing an unexpected agent in addition to the intended substance [14, 24]. This aspect might point out the awareness among Berlin nightlife attendees of the risks associated with uninformed drug use and polysubstance use, and underlines the potential harm reduction effects of drug checking [25].

In accordance with nightlife attendees from other surveys, the participants stated brief counseling accompanying presenting the analysis results to be useful [12, 13]. The counseling could be used to apply prevention on another level than just perform a chemical analysis, for example, inform about the potential harms of specific substances detected by the analysis or of illicit drug use in general. This might lead to a low-threshold contact to illicit drug use by nightlife attendees who are otherwise difficult to address with preventive measures [5].

Most participants indicated to acquire their substances prior to the events at which they use them; hence, users may check their substances in advance, using stationary drug-checking services, as planned by the Berlin public health administration. Previous studies, however, showed that on-site drug-checking services might be used by more nightlife attendees, in general, and high-risk users, in particular, compared to stationary services [6, 26]. Future studies might, therefore, investigate if this also applies for Berlin nightlife attendees to prospectively implement on-site services also. Moreover, most participants stated to get their substances either from friends or familiar dealers. First, drug-checking results could, thus, be shared with other nightlife attendees, creating a multiplier effect. This phenomenon has also been shown in previous studies, in which data on samples containing unexpected or highly dosed substances have been exchanged among users [6]. Second, the results could provide an incentive for dealers to sell less adulterated substances − even though participants did not state “testing” their dealer as one of the most important reasons to use drug checking. The latter mostly included avoiding cutting agents or unexpected psychotropic substances; however, avoiding overdoses was rated slightly less important. Given the major risk factors associated with drug overdoses [27], this aspect could be emphasized in counseling services. By securing anonymity and immunity from criminal prosecution, the planned drug-checking service in Berlin would address the participants' main discouraging reasons which have also been pointed out by nightlife attendees in previous studies [6, 13].

With regard to the association between these aspects and demographic variables, we found that with age, the motivation to avoid overdoses (and other psychoactive substances [trend]) plays a higher role, as opposed to “just curiosity of ingredients,” which was negatively correlated with age. This finding might reflect an increasing awareness toward complications in nightlife which may come along with nightlife experience (e.g., witnessing overdoses or having experienced overdoses themselves). Experience, in turn, is supposedly associated with age. However, level of “nightlife experience” was not evaluated in our study, so this aspect remains hypothetical and may be addressed by further research. Apparently, concerns on anonymity and data privacy also increase with age, which might be explained by the assumption that for people of higher age, potentially more is at stake when engaging in illegal activities (e.g., losing job) as opposed to younger people who are still attending college or apprenticeship.

With regard to the anticipated reaction on test results, an association with gender could be found (see Table 2); for example, nominally less female (as opposed to male) participants stated to take the usual amount in case of high potency (3.7 vs. 5.5%) and were more willing to discharge the sample (4.6 vs. 0.8%). Also, in case of only unexpected substances, nominally more female participants stated to take less than male participants (4.6 vs. 1%). This finding may reflect the widely known tendency of men to show riskier substance use and lower health awareness than women [28, 29, 30].

The prevalence of substance use among participants of this study was higher than that in studies from other party scenes, but comparably high to prevalences in Berlin's party scene previously assessed [20, 26, 31]. This might be linked to Berlin's internationally known club scenes and highlights the need for preventive measures in Berlin [32, 33]. The previously mentioned concern expressed by critics of drug checking about substance use becoming even more prevalent following the implementation of drug checking does not build on empirical data but rather on hypothetical considerations [17, 19]. Contrasting this, evidence indicates that drug checking could in fact decrease (heavy) illicit drug use [10, 34]. Potential encouraging aspects of drug checking to start substance use was not covered by our questionnaire, so our data cannot contribute new evidence to this controversy. This aspect may be important to consider in further research though.

The most prevalently used illicit substances were typical party drugs (e.g., cannabis, amphetamine, 3,4-methyl-enedioxy-methamphetamine, and cocaine). However, participants unknowingly using new psychoactive substances (NPSs) as adulterants might have led to false low-prevalence rates of NPS use. By showing the actual ingredients of the submitted samples, drug checking could improve monitoring trends on the Berlin NPS market and help reduce risks associated with NPS use [2, 35].

Limitations

When discussing a potential effect of drug checking on consumption patterns, one has to keep in mind that the findings of this study are only based on hypothetical considerations from a questionnaire and may not directly reflect real-life decisions. Studies examining the latter showed slightly lower rates of users rejecting their sample when in fact confronted with unexpected substances [3, 14]. Further studies could thus investigate the actual impact of drug checking on Berlin nightlife attendees' consumption patterns after being deployed.

Since only limited details about the planned pilot project were known at the time the questionnaire was created, it did not cover if drug-checking users will be willing to wait several days for their results. Taking into consideration that only about half of the nightlife attendees in previous studies were willing to wait that long, future studies might examine the waiting time's impact on drug-checking users in Berlin [6, 9, 13].

Even though studies of other party scenes showed comparably educational attainments, the participants stated a considerably higher level of education than people of the same age from the Berlin general population and also from the recent study (SuPrA-Survey) of the Berlin party scene [20, 36, 37]. The high level of education, in general, could indicate a self-selection bias inasmuch as nightlife attendees with a higher educational background were more willing to reflect on their consumption patterns and argue with prevention measures. Higher level of education than that in the SuPrA-Survey may indicate a further sample bias as it is conceivable that users with particular interest in drug checking show a higher level of health/risk awareness which may be associated with a higher educational level. This particular self-selection bias also has to be taken into account concerning the high prevalence rates when deploying a questionnaire specifically addressing drug checking. Contrary to the level of education, the participants' mean age was comparable to the SuPrA-Survey but considerably higher than that in studies examining nightlife attendees' attitudes toward drug checking in other cities [6, 9, 20]. This might be explained by the fact that many clubs in Berlin are restricted to people older than 21 years as opposed to other German cities or other countries (18 years or older), probably raising the mean age of Berlin's party scene, but it also poses the question of external validity of the data collected [9]. Drug-checking services and future studies, however, ought to target young nightlife attendees in particular since they have shown to use most illicit substances and, therefore, are at a higher risk of facing overdosed substances or harmful adulterants [38].

Statement of Ethics

This study has been approved by the institutional ethics committee, and all participants received information about the study beforehand.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any funding.

Author Contributions

F.B.: project coordination, study design, and manuscript drafting. J.H.: data collection, data handling, and manuscript drafting. F.E.: data collection and data handling. L.V.: data collection, supportive administrative tasks, and proofreading. L.R.: data collection and supportive administrative tasks. S.G.: participation in study design, consultation, and proofreading the manuscript. A.S.: administrative supervision of the project and proofreading the manuscript. S.K.: support and supervision of all parts of the project and manuscript drafting.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tibor Harrach and Dr. Tomislav Majic for their valuable contribution to this article.

References

- 1.Vidal Giné C, Ventura Vilamala M, Fornís Espinosa I, Gil Lladanosa C, Calzada Álvarez N, Fitó Fruitós A, et al. Crystals and tablets in the Spanish ecstasy market 2000–2014: are they the same or different in terms of purity and adulteration? Forensic Sci Int. 2016;263:164–8. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betzler F, Heinz A, Köhler S. [Synthetic drugs: an overview of important and newly emerging substances] Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2016;84((11)):690–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-117507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saleemi S, Pennybaker SJ, Wooldridge M, Johnson MW. Who is ‘Molly’? MDMA adulterants by product name and the impact of harm-reduction services at raves. J Psychopharmacol. 2017;31((8)):1056–60. doi: 10.1177/0269881117715596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunt T. Drug checking as a harm reduction tool for recreational drug users: opportunities and challenges. 2017. Available from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/attachments/6339/EuropeanResponsesGuide2017_BackgroundPaper-Drug-checking-harm-reduction_0.pdf.

- 5.Grabenhofer S, Kociper K, Nagy C, Luf A, Schmid R. Drug checking und aufklärung vor ort in der niedrigschwelligen präventionsarbeit. In: von Heyden M, Jungaberle H, Majić T, editors. Handbuch psychoaktive substanzen. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2018. pp. p.327–38. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barratt MJ, Bruno R, Ezard N, Ritter A. Pill testing or drug checking in Australia: acceptability of service design features. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37((2)):226–36. doi: 10.1111/dar.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunt TM, Nagy C, Bücheli A, Martins D, Ugarte M, Beduwe C, et al. Drug testing in Europe: monitoring results of the trans European drug information (TEDI) project. Drug Test Anal. 2017;9((2)):188–98. doi: 10.1002/dta.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keijsers L, Bossong MG, Waarlo AJ. Participatory evaluation of a Dutch warning campaign for substance-users. Health Risk Soc. 2008;10((3)):283–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiese S, Verthein U. Drug-checking für drogenkonsumenten: risiken und potenziale. SUCHT. 2014;60((6)):315–22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bücheli A, Quinteros–Hungerbühler I, Schaub M. Evaluation der partydrogenprävention in der stadt zürich. Suchtmagazin. 2010;5:41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston J, Barratt MJ, Fry CL, Kinner S, Stoové M, Degenhardt L, et al. A survey of regular ecstasy users' knowledge and practices around determining pill content and purity: implications for policy and practice. Int J Drug Policy. 2006;17((6)):464–72. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Day N, Criss J, Griffiths B, Gujral SK, John-Leader F, Johnston J, et al. Music festival attendees' illicit drug use, knowledge and practices regarding drug content and purity: a cross-sectional survey. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15((1)):1. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0205-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sande M, Šabić S. The importance of drug checking outside the context of nightlife in Slovenia. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15((1)):2. doi: 10.1186/s12954-018-0208-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martins D, Barratt M, Pires C, Carvalho H, Vilamala M, Espinosa I, et al. The detection and prevention of unintentional consumption of DOx and 25x-NBOMe at Portugal's boom festival. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32((3)):e2608. doi: 10.1002/hup.2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherman SG, Morales KB, Park JN, McKenzie M, Marshall BDL, Green TC. Acceptability of implementing community-based drug checking services for people who use drugs in three United States cities: baltimore, Boston and Providence. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;68:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rouhani S, Park JN, Morales KB, Green TC, Sherman SG. Harm reduction measures employed by people using opioids with suspected fentanyl exposure in Boston, Baltimore, and Providence. Harm Reduct J. 2019;16((1)):39. doi: 10.1186/s12954-019-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winstock AR, Wolff K, Ramsey J. Ecstasy pill testing: harm minimization gone too far? Addiction. 2001;96((8)):1139–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dundes L. DanceSafe and ecstasy: protection or promotion? J Health Soc Policy. 2003;17((1)):19–37. doi: 10.1300/J045v17n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider J, Galettis P, Williams M, Lucas C, Martin JH. Pill testing at music festivals: can we do more harm? Intern Med J. 2016;46((11)):1249–51. doi: 10.1111/imj.13250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Betzler F, Ernst F, Helbig J, Viohl L, Roediger L, Meister S, et al. Substance use and prevention programs in Berlin's party scene: results of the SuPrA-study. Eur Addict Res. 2019;25((6)):283–92. doi: 10.1159/000501310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrach T, Schmolke R. “Das Gute daran: Es könnte Leben retten.” − Drug-Checking-Politik in Deutschland. In: Tögel-Lins K, Werse B, Stöver H, editors. Checking Drug-Checking: Potentiale für Prävention, Beratung, Harm Reduction und Monitoring. Frankfurt Am Main: Fachhochschulverlag; 2019. pp. p.121–49. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nestler C. Zulässigkeit und rechtliche Rahmenbedingungen von Drug-Checking unter dem Betäubungsmittelgesetz. In: Tögel-Lins K, Werse B, Stöver H, editors. Checking Drug-Checking: Potentiale für Prävention, Beratung, Harm Reduction und Monitoring. Frankfurt Am Main: Fachhochschulverlag; 2019. pp. p.69–95. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brülls M. Drug-checking in Berlin: der geprüfte rausch. 2019. Available from: https://taz.de/Drug-Checking-in-Berlin/!5607478/

- 24.Valente H, Martins D, Carvalho H, Pires CV, Carvalho MC, Pinto M, et al. Evaluation of a drug checking service at a large scale electronic music festival in Portugal. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;73:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Connor JP, Gullo MJ, White A, Kelly AB. Polysubstance use: diagnostic challenges, patterns of use and health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014;27((4)):269–75. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hungerbuehler I, Buecheli A, Schaub M. Drug checking: a prevention measure for a heterogeneous group with high consumption frequency and polydrug use − evaluation of zurich's drug checking services. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armenian P, Mamantov TM, Tsutaoka BT, Gerona RR, Silman EF, Wu AH, et al. Multiple MDMA (Ecstasy) overdoses at a rave event: a case series. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28((4)):252–8. doi: 10.1177/0885066612445982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grossbard JR, Mastroleo NR, Kilmer JR, Lee CM, Turrisi R, Larimer ME, et al. Substance use patterns among first-year college students: secondary effects of a combined alcohol intervention. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39((4)):384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenberg D, Golberstein E, Whitlock JL. Peer effects on risky behaviors: new evidence from college roommate assignments. J Health Econ. 2014;33:126–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO . Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. World Health Organisation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hannemann TV, Kraus L, Piontek D. Consumption patterns of nightlife attendees in munich: a latent-class Analysis. Subst Use Misuse. 2017;52((11)):1511–21. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1290115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coldwell W. Nightlife reports: clubbing in Berlin. The Guardian Online; 2016. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2016/jul/15/berlin-clubs-nightlife-germany-techno. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pareles J. Berlin, still partying in the ruins. The New York Times Online; 2014. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/23/travel/in-berlin-still-partying-in-the-ruins.html. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Benschop A, Rabes M, Korf DJ. Pill testing, ecstasy & prevention. Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Butterfield RJ, Barratt MJ, Ezard N, Day RO. Drug checking to improve monitoring of new psychoactive substances in Australia. Med J Aust. 2016;204((4)):144–5. doi: 10.5694/mja15.01058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordfjærn T, Bretteville-Jensen AL, Edland-Gryt M, Gripenberg J. Risky substance use among young adults in the nightlife arena: an underused setting for risk-reducing interventions? Scand J Public Health. 2016;44((7)):638–45. doi: 10.1177/1403494816665775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niemann-Ahrendt K. Bildungsstand der Bevölkerung in Berlin und Brandenburg. Z Amt Stat. 2016:40–3. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Havere T, Vanderplasschen W, Broekaert E, De Bourdeaudhui I. The influence of age and gender on party drug use among young adults attending dance events, clubs, and rock festivals in Belgium. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44((13)):1899–915. doi: 10.3109/10826080902961393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]