Abstract

Background

The use of professional interpretation is associated with improvements in overall healthcare of patients with limited English proficiency (LEP). For these patients, it is important to understand whether quality of professional interpretation in-person is preserved using remote interpretation modalities (video-conferencing, telephone).

Objective

To compare patient perceptions of professional interpretation quality delivered in-person, via video-conferencing, or via telephone during in-person primary care clinical visits.

Design

Secondary analysis of a telephone survey conducted within 1 week after a primary care visit

Participants

The 326 Chinese and Latino survey participants with LEP who reported using a professional interpreter—in-person, video medical conferencing (VMI), or telephone—during their visit

Main Measures

Six items about the quality of interpretation: five detailed items scored as a scale, and a sixth overall quality item (range 1 = poor to 5 = excellent)

Key Results

While there was a range for all modalities, most patients reported “very good” or “excellent” quality on both the scale and the overall single quality measure. In adjusted analysis, patients rated VMI quality the highest, followed by in-person and then telephone on both the 5-item scale (adjusted means: VMI 3.91, in-person 3.86, telephone 3.73) and the overall single quality item (adjusted means: VMI 3.94, in-person 3.85, telephone 3.83); however, no two-way comparisons were statistically significant (p values ranged 0.15–0.95).

Conclusions

Our results highlight that, overall, the interpretation experience among patients who used any type of professional interpretation was positive, and that the quality found with in-person interpretation is preserved for remote modalities. Health systems should consider a multimodality approach to interpreter service provision including options for accessing professional interpreters via all three modalities based on communication and access needs.

INTRODUCTION

The use of professional interpretation in primary care is associated with improvements in overall healthcare of patients with limited English proficiency (LEP).1 Professional interpreters allow for better communication between patients and providers, resulting in reduced disparities in healthcare services, and increased satisfaction among all those involved in the clinical encounter.1, 2

In-person professional interpretation is the most studied interpretation modality, and is often considered the “gold standard” due to its demonstrated ability to improve satisfaction, processes, and outcomes of care.1, 3 The quality of different modalities of interpretation—in-person or remote (i.e., telephone or video)—has been studied from the physician and interpreter perspective;3, 4 however, less is known about the patient perspective on quality. A few studies have reported on patient perspectives of interpreter quality without distinguishing the modality of interpretation.5, 6 One study compared quality across the three modalities using a scale that combined quality of interpretation with quality of the clinician to assess overall quality of the encounter.7 Other studies largely focused on patient satisfaction with professional interpretation, often comparing one modality of professional interpretation to not having a professional interpreter at all.8–11 A systematic review of patient satisfaction with interpreter by modality also found that patients are generally satisfied with interpreters regardless of modality, as long as those interpreters are professionally trained.12

While this previous literature suggests the importance of measuring interpreter quality and demonstrates patient satisfaction with professional interpretation, there remains a gap in detailed understanding of how the quality of interpreter-specific communication may differ across interpretation modality from a patient perspective. For patients with LEP, it is important to understand whether quality of professional interpretation in-person is preserved in remote modalities. We set out to compare patient perceptions of professional interpretation quality delivered in-person, via video-conferencing, or via telephone during in-person primary care clinical visits.

METHODS

Design

The current study is a secondary analysis utilizing data from the Language Access System Improvement (LASI) study. This observational study was designed to evaluate the effects of a system intervention that (i) increased access to video professional interpretation while (ii) certifying bilingual physicians’ language skills on communication and clinical outcomes. The larger LASI study occurred in two phases: “pre”—before the system intervention was implemented (February 2014–April 2014), and “post”—after the implementation of the system intervention (January 2016–July 2017). Because VMI was not available until the post study period, and in order to compare across three professional interpretation modalities (in-person, VMI, and telephone), only patients from the post sample were included in this analysis. The methods have previously been reported elsewhere, and are briefly described here.13, 14

Setting

The LASI study took place in a large urban, academic primary care practice. In the time-frame for this analysis, in-person, VMI, and telephone modalities of professional interpretation were regularly available to facilitate communication; in-person staff interpreters needed to be scheduled, VMI and telephone interpreters were available on demand from contracted vendors.

Participants

Patients were eligible to participate in the LASI study if they were ≥ 40 years old; received primary care within the practice; self-identified as Chinese or Latino; preferred to receive their medical care in English, Cantonese, Mandarin, or Spanish; and were able to complete a telephone survey. Within 1 week following a primary care (index) visit, patients were contacted by corresponding bilingual and bicultural research assistants, and were invited to complete a telephone survey about their communication experiences during their index visit. Participants were categorized as having limited English proficiency (LEP) using our previously validated algorithm.15 Only those participants with LEP who reported on the survey that professional interpretation was provided at their index visit were included in this analysis.

Outcome Measure

Patients who reported using a professional interpreter—either in-person, VMI, or via telephone—during their index visit answered five “detailed” items and a sixth “overall” item about the quality of interpretation: (1) How was the interpreter at listening to what you had to say? (2) How was the interpreter at explaining what you said to the doctor? (3) How was the interpreter at helping you understand your medical problems? (4) How was the interpreter at helping you understand medical test results? (5) How was the interpreter at helping you understand your treatment plan? (6) Overall, how was the quality of the interpretation? The items used five ordered response options (1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent), and were adapted from a validated communication measure, Interpersonal Processes of Care,16 to be specific to the interpretation rather than to the provider’s communication. The a priori plan was to score responses to the five “detailed” items as a scale and leave the sixth “overall” item as a separate single-item measure.

Key Independent Variables and Covariates

Among patient-specific characteristics, age, gender, education level, preferred language, and English ability were self-reported. Preferred language was designated by patient responses to the question, “In what language do you prefer to receive your medical care?” and English ability was based on the US Census question “How well to you speak English?” LEP status was determined using our previously validated algorithm which combines preferred language and English ability.15 Health literacy was determined using a single, validated question, “How confident are you filling out medical forms by yourself?”17, 18 Additional characteristics were pulled from the electronic medical record: Elixhauser comorbidities19 and visit-level characteristics including whether the index visit was with the patient’s own primary care provider or not, the number of problems addressed during the visit, the number of clinic visits in the prior 12 months, and the length of time as an established patient in the practice.

Statistical Analysis

We performed descriptive analyses on demographic characteristics to assess their distributions across the different modes of professional interpretation. A confirmatory factor analysis model of the five “detailed” interpretation quality items fit very well: comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.997.20 Next, scale scores were calculated as each patient’s mean response to the five items resulting in a scale with theoretical range from 1 (“poor”) to 5 (“excellent”). Internal consistency of the corresponding 5-item scale also was excellent: Cronbach’s alpha = 0.964. Distributions of the different modes of professional interpretation were assessed separately for the 5-item scale and the sixth “overall” quality item. We fit multivariable linear mixed models of each outcome (5-item quality scale, single-item “overall” quality score). Each model included random intercepts for visit physicians as well as covariates describing patient language, age, gender, education, comorbidities, whether the provider was the patient’s primary care provider, the number of problems listed in the visit note, health literacy, frequency of visits in the past year, and length of time as a patient within the practice, and clustering within physicians. In addition, interaction effects (up to three-way) between language, education, and interpreter modality were initially considered and a backward elimination process dropped non-significant interaction terms (p > 0.10). Analyses were conducted using Stata version 14.2 (College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California, San Francisco.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Among the 1,697 eligible patients in the “post” period who were reached during the week after their index primary care visit, 1181 (69.6%) agreed to participate in the telephone survey. Among participants, 735 were categorized as having LEP. Of those with LEP, 326 reported using a professional interpreter during their index primary care visit and are included in this analysis.

Among the 326 participants, most were Cantonese-speakers (55.8%), female (64.4%), and saw their own primary care provider during the index visit (62.9%). Almost three-quarters of the participants (73.6%) had professional interpreter services during their visit via VMI, 15.6% in-person, and 10.7% via telephone. On average, participants with a VMI interpreter had lower educational attainment and were older, while those with an in-person interpreter had more complex visits based on the number of problems addressed in their visit note (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of LEP Patients by Mode of Professional Interpretation (N = 326)a

| Total | In-person | VMI | Telephone | p valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 326 | N = 51 | N = 240 | N = 35 | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||||

| Preferred language to receive medical care | |||||

| Cantonese | 182 (55.8) | 34 (66.7) | 134 (55.8) | 34 (50.8) | 0.001 |

| Mandarin | 84 (25.8) | 11 (21.6) | 67 (27.9) | 11 (16.4) | |

| Spanish | 60 (18.4) | 6 (11.8) | 39 (16.3) | 22 (32.8) | |

| Age (mean ± SE) | 69.2 ± 0.6 | 66.2 ± 1.3 | 70.0 ± 0.8 | 67.7 ± 2.1 | 0.04 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 210 (64.4) | 41 (80.4) | 145 (60.4) | 24 (68.6) | 0.04 |

| Male | 116 (35.6) | 10 (19.6) | 95 (39.6) | 11 (31.4) | |

| Education | |||||

| Less than high school | 168 | 32 (62.8) | 117 (48.8) | 19 (54.3) | 0.01 |

| High school diploma | 61 (18.7) | 11 (21.6) | 40 (16.7) | 10 (28.6) | |

| AA or some college | 31 (9.5) | 6 (11.8) | 22 (9.2) | 3 (8.6) | |

| College degree or higher | 66 (20.3) | 2 (3.9) | 61 (25.4) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Health literacy | |||||

| Inadequate | 77 (23.6) | 20 (39.2) | 48 (20.0) | 9 (25.7) | 0.02 |

| Adequate | 249 (76.4) | 31 (60.8) | 192 (80.0) | 26 (74.3) | |

| Number of comorbiditiesb | |||||

| (mean ± SE) | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.3 | 0.02 |

| Visit characteristics | |||||

| Visit with PCP or not | |||||

| No | 121 (37.1) | 13 (25.5) | 90 (37.5) | 18 (51.4) | 0.04 |

| Yes | 205 (62.9) | 38 (74.5) | 150 (62.5) | 17 (48.6) | |

| Number of problems addressed during | |||||

| the visit (mean ± SE) | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 0.14 |

| Number of visits in past 12 months | |||||

| (mean ± SE) | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.58 |

| Length of time as a patient (in months) | |||||

| (mean ± SE) | 29.1 ± 0.7 | 28.4 ± 2.0 | 29.2 ± 0.7 | 29.6 ± 1.4 | 0.89 |

ap value adjusted for clustering of patients within physicians

bElixhauser-based comorbidity summary (Elixhauser et al. Med Care 1998; 36:8–27)

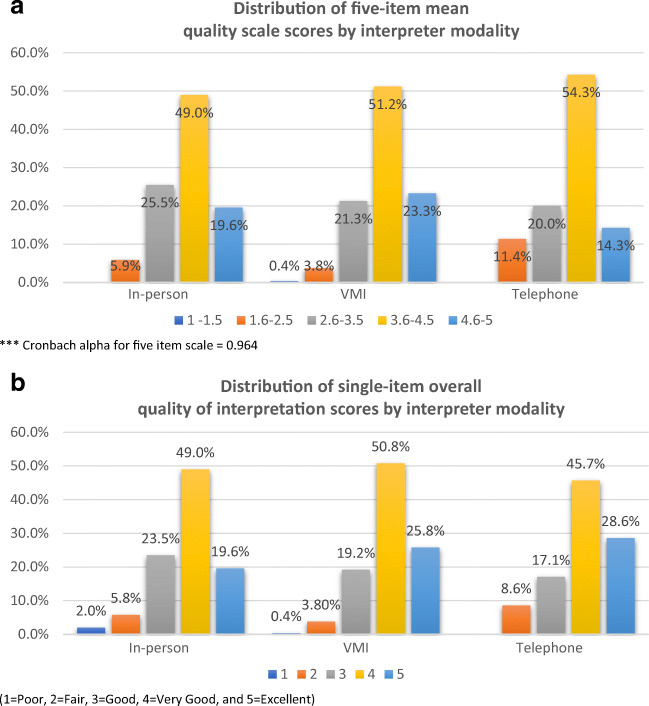

The figure shows the distributions of the 5-item scale (Fig. 1a) and single-item overall quality measure (Fig. 1b), stratified by interpreter modality. While there was a range for all modalities, most patients reported “very good” or “excellent” quality on the scale and on the overall quality measure. On the 5-item scale, the proportion scoring very good/excellent was highest for VMI and lowest for telephone interpretation. Scores were more similarly distributed for the three modalities on the single-item measure.

Figure 1.

a Distribution of five-item mean quality scale scores by interpreter modality. b Distribution of single-item overall quality of interpretation scores by interpreter modality.

In the mixed linear models, none of the interaction effects approached statistical significance and all were dropped (p values ranged from 0.19 to 0.35 for the 5-item scale and from 0.18–0.69 for the single-item measure). Table 2 reports the unadjusted and model-adjusted means by interpretation modality for both outcomes. All adjusted and unadjusted means ranged from 3.73 to 3.98, suggesting average ratings that approached “very good.” In the adjusted analysis, patients rated VMI quality the highest, followed by in-person and then telephone; however, none of the pairwise comparisons was significant.

Table 2.

Mean LEP Patient Responses to the 5-Item Quality of Interpretation Scale and Single-Item Overall Quality of Interpretation Score, Stratified by Professional Interpretation Modality (N = 326)

| Unadjusted Means ± SE | Adjusted Means ± SE | p values** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Five-item quality of interpretation scale*** | |||

| In-persona | 3.82 ± 0.13 | 3.86 ± 0.11 | a vs b = 0.61 |

| VMIb | 3.95 ± 0.05 | 3.91 ± 0.04 | a vs c = 0.44 |

| Telephonec | 3.79 ± 0.13 | 3.73 ± 0.13 | b vs c = 0.15 |

| Single-item overall quality of interpretation score | |||

| In-persona | 3.78 ± 0.14 | 3.85 ± 0.12 | a vs b = 0.39 |

| VMIb | 3.98 ± 0.05 | 3.94 ± 0.04 | a vs c = 0.95 |

| Telephonec | 3.94 ± 0.15 | 3.83 ± 0.14 | b vs c = 0.41 |

1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, 5 = excellent

*Adjusted means are from linear mixed models controlling for patient language, age, gender, education, comorbidities, whether the provider was the patient’s primary care provider (PCP), the number of problems listed in the visit note, health literacy, frequency of visits in the past year, and length of time as a patient within the practice

**p values adjusted for clustering of patients within physicians

***Cronbach alpha for 5-item scale = 0.964

Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted means by interpretation modality for the 5-item quality scale and the single-item overall quality measure. The adjusted and unadjusted means for both the 5-item quality scale and the single-item overall measure were in the good (3) to very good (4) range. In the adjusted analysis, patients rated VMI quality the highest, followed by in-person and then telephone; however, no two-way comparisons were significant.

DISCUSSION

Our results highlight that, overall, the interpretation experience among patients who used any type of professional interpretation was positive, and the quality found with in-person is preserved for remote modalities. While there were differences in patient characteristics in terms of who received each modality of interpretation, after adjusting for these differences, overall quality remained similar across modalities with a trend toward VMI being a little better than in-person and telephone being a little worse. This is consistent with the literature on patient satisfaction with professional interpretation across modality12, and with another study which assessed patient perspective of overall encounter quality for visits with different professional interpretation modalities.7

Although the literature on quality of interpretation by modality is limited, our group’s previous work showed that from the interpreter perspective, telephone interpretation was adequate for simple information exchange, but VMI offered better communication for more complex clinical visits,4 and from the physician’s perspective, VMI and in-person interpretation offered similar quality of interpretation, although in-person interpretation allowed for more nuance particularly when addressing cultural differences.3 Aligned with our current findings, one other study found that both patients and clinicians preferred VMI over in-person professional interpretation.21

Our data do not give us specific information on the exact elements of different interpretation modalities that may have shaped patients’ assessments. However, compared to telephone, VMI potentially allows for more interpersonal connection and improved context of who is in the room, while maintaining the ability to read visual cues and eye contact that exists with in-person interpretation. Additionally, similar to interpretation via telephone, VMI has the advantage over scheduled in-person interpretation of on-demand availability, allowing the VMI interpreter to be present throughout the entire visit without time limitations. VMI appears to be a very good option to deliver access to professional interpretation while maintaining quality. However, in-person professional interpretation likely continues to have advantages in particular clinical situations and for particular patients.3, 4, 22 Likewise, there may be times when interpretation via telephone is the only available option, and it is reassuring that patients experiencing this type of interpretation generally rate the quality to be good.

While this study was conducted in the pre-COVID-19 era, it has implications for clinical practice during the pandemic. Our finding that patients report good interpretation quality via remote modalities supports efforts to ensure access to professional interpretation via telephone and video for remote clinical visits.23 Once the pandemic ends, any systems put into place for remote access interpretation during remote clinical visits can be then incorporated into a more general multimodality approach to interpreter service provision for in-person visits.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, data for the LASI study were collected at a single academic practice within a primary care setting. Therefore, our results may not generalize to different types of primary care practices or other specialties. However, the focus in a large, diverse primary care setting did allow for a patients’ perspective on interpretation quality for a range of clinical encounters addressing multiple clinical concerns. Additionally, while patient perspectives are extremely important, our findings of patient-reported outcomes may not reflect the actual quality of professional interpretation. Also, the number of in-person and telephone visits was small, limiting our power to detect differences between modalities. With a larger sample, we may have seen a significant mean difference between modalities, particularly between telephone versus VMI and in-person interpretation, although the clinical significance of that difference may have remained small. We also were not able to compare perceptions of the quality of interpretation by modality for the same patient in this observational study, and it may be that different interpretation modalities may be more or less optimal for different types of patients and clinical contexts, contributing to modality choice for any given visit. Our covariate adjustment did address differences in patient and visit characteristics, but it is possible that some important covariates were unmeasured and thus not included in our model. However, this study does represent real practice in a setting where adequate access to professional interpretation is available.

CONCLUSION

In summary, patients reported professional interpretation to be of good-quality across modality of interpretation, with slightly higher marks for video-conferencing and in-person over telephone. Given the known variation in communication needs for specific clinical situations and the reassurance our data provides of good-quality interpretation across modalities, health systems should consider a multimodality approach to interpreter service provision including options for accessing professional interpreters via all three modalities based on communication and access needs. This type of approach has been shown to be successful,24 and implementation could be tailored to individual health system settings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge and thank the patients and staff of the Division of General Internal Medicine at the University of California San Francisco for their participation in this study.

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®) Award (AD-1409-23627) and NIH grant P30AG015272. The statements presented are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Karliner LS, Jacobs EA, Chen AH, Mutha S. Do Professional Interpreters Improve Clinical Care for Patients with Limited English Proficiency? A Systematic Review of the Literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs EA, Lauderdale DS, Meltzer D, Shorey JM, Levinson W, Thisted RA. Impact of interpreter services on delivery of health care to limited-English-proficient patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):468–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, Karliner LS, O’Brien H, Gregorich SE, Pérez-Stable EJ. Clinician ratings of interpreter mediated visits in underserved primary care settings with ad hoc, in-person professional, and video conferencing modes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1):301–317. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price EL, Pérez-Stable EJ, Nickleach D, López M, Karliner LS. Interpreter perspectives of in-person, telephonic, and videoconferencing medical interpretation in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;87(2):226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lor M, Xiong P, Schweia RJ, Bowers B, Jacobs EA. Limited English proficient Hmong- and Spanish-speaking patients’ perceptions of the quality of interpreter services. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;54:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talamantes E, Moreno G, Guerrero LR, Mangione CM, Morales LS. Hablamos juntos (together we speak): a brief patient-reported measure of the quality of interpretation. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2014;5:87–92. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S68699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Locatis C, Williamson D, Gould-Kabler C, et al. Comparing In-Person, Video, and Telephonic Medical Interpretation. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(4):345–350. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lion KC, Brown JC, Ebel BE, et al. Effect of Telephone vs Video Interpretation on Parent Comprehension, Communication, and Utilization in the Pediatric Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(12):1117–1125. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gany F, Leng J, Shapiro E, et al. Patient satisfaction with different interpreting methods: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):312–318. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0360-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee LJ, Batal HA, Maselli JH, Kutner JS. Effect of Spanish Interpretation Method on Patient Satisfaction in an Urban Walk-in Clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):641–646. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo D, Fagan MJ. Satisfaction with Methods of Spanish Interpretation in an Ambulatory Care Clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):547–550. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph C, Garruba M, Melder A. Patient satisfaction of telephone or video interpreter services compared with in-person services: a systematic review. Aust Health Rev. 2018;42(2):168–177. doi: 10.1071/AH16195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nouri SS, Pathak S, Livaudais-Toman J, et al. Use and Usefulness of After-Visit Summaries by Language and Health Literacy Among Latinx and Chinese Primary Care Patients. J Health Commun. 2020;25(8):632-639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Garcia ME, Hinton L, Gregorich SE, Livaudais-Toman J, Kaplan C, Karliner L. Unmet Mental Health Need Among Chinese and Latino Primary Care Patients: Intersection of Ethnicity, Gender, and English Proficiency. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1245–1251. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karliner LS, Napoles-Springer AM, Schillinger D, Bibbins-Domingo K, Pérez-Stable EJ. Identification of Limited English Proficient Patients in Clinical Care. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1555–1560. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0693-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stewart AL, Nápoles-Springer AM, Gregorich SE, Santoyo-Olsson J. Interpersonal Processes of Care Survey: Patient-Reported Measures for Diverse Groups. Health Services Research. 2007;42(3p1):1235–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkar U, Schillinger D, López A, Sudore R. Validation of self-reported health literacy questions among diverse English and Spanish-speaking populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(3):265–271. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1552-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107(2):238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wofford JL, Campos CL, Johnson DA, Brown MT. Providing a Spanish interpreter using low-cost videoconferencing in a community health centre: a pilot study using tablet computers. Inform Prim Care. 2012;20(2):141–146. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v20i2.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuot DS, Lopez M, Miller C, Karliner LS. Impact of an easy-access telephonic interpreter program in the acute care setting: an evaluation of a quality improvement intervention. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(12)38011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diamond LC, Jacobs EA, Karliner L. Providing equitable care to patients with limited dominant language proficiency amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(8):1451–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marshall LC, Zaki A, Duarte M, et al. Promoting Effective Communication with Limited English Proficient Families: Implementation of Video Remote Interpreting as Part of a Comprehensive Language Services Program in a Children’s Hospital. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2019;45(7):509–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]