Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, degenerative disorder that mainly results in memory loss and a cognitive disorder. Although the cause of AD is still unknown, a minor percentage of AD cases are produced by genetic mutations in the presenilin-1 (PSEN1) gene. Differentiated neuronal cells derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) of patients can recapitulate key pathological features of AD in vitro; however, iPSCs studies focused on the p.E280 A mutation, which afflicts the largest family in the world with familial AD, have not been carried out yet. Although a link between the loss of the Y (LOY) chromosome in peripheral blood cells and risk for AD has been reported, LOY-associated phenotype has not been previously studied in PSEN1 E280 A carriers. Here, we report the reprogramming of fibroblast cells into iPSCs from a familial AD patient with the PSEN1 E280 A mutation, followed by neuronal differentiation into neural precursor cells (NPCs), and the differentiation of NPCs into differentiated neurons that lacked a Y chromosome. Although the PSEN1 E280 A iPSCs and NPCs were successfully obtained, after 8 days of differentiation, PSEN1 E280 A differentiated neurons massively died reflected by release and/ or activation of death markers, and failed to reach complete neural differentiation compared to PSEN 1 wild type cells.

Keywords: Familial Alzheimer disease, Chromosome Y, E280A, iPSCs, PSEN1

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by loss of memory and cognitive impairment mainly due to severe cellular loss and dysfunction of the basal forebrain cholinergic neurons and cholinergic axons in the cortex [1]. This dysfunction is produced by the formation of extracellular plaques of neuritic amyloid-β (Aβ) and intracellular tau protein aggregates, called neurofibrillary tangles [2]. Genetic abnormalities associated with early onset AD development include the directly-associated mutations occurring in the amyloid precursor protein (APP), presenilin-1 (PSEN1) and presenilin-2 (PSEN2) genes [3]. Specifically, the PSEN1 E280 A (p.Glu280Ala) mutation predisposes individuals to develop autosomal dominant AD, usually relatively early in adulthood [4]. PSEN1 E280 A carriers show evidence of preclinical AD in the years and decades before their estimated clinical onset, including elevated cortical amyloid levels, smaller hippocampal volumes and higher plasma Aβ1-42 measurements [5,6].

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are pluripotent cells derived from somatic cells by the ectopic expression of key reprogramming factors under embryonic stem cell (ESC) culture conditions [7,8]. Similar to ESCs, the iPSCs are undifferentiated cells able to self-renew in vitro and to generate the three primary germ layers of the embryo. Interestingly, iPSCs-derived neurons of patients are able to recapitulate in vitro key pathological features of many diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders such as AD [9,10]. Accordingly, iPSCs-derived neurons from sporadic and familial AD exhibit high levels of cellular stress, phosphorylated tau, Aβ peptide, as well as the presence of intra- and extracellular amyloid aggregates [11,12].

Recently, a link between the loss of Y (LOY) chromosome in peripheral blood cells and the risk for AD has been reported [13]. Therefore, males with AD diagnosis had higher degrees of LOY mosaicism compared to controls. Furthermore, in two prospective studies, men with LOY at blood sampling had a greater risk to be diagnosed with AD during the follow-up time. Thus, although LOY might explain why males on average live shorter lives than females, the LOY-associated phenotype have not been studied previously in PSEN1 E280 A carriers. Here, we report the derivation and neuronal differentiation of an iPSCs clone lacking a Y chromosome obtained from a familial AD patient with a PSEN1 E280 A mutation. We addressed the possible pathological roles of both accumulation of extracellular Aβ1-42 and the LOY during neural differentiation process of this iPSCs clone compared with a control.

2. Methods

2.1. Human iPSCs lines

Reprogramming of human primary skin fibroblasts from two adult donors (Control 3-11: Male; and PSEN305: male carrying PSEN1 E280 A mutation) was performed as described previously using a single, multicistronic lentiviral vector encoding OCT4, SOX2, KLF4 and MYC [14]. Donors provided written informed consent in accordance with the Medical Ethical Committee of University of Antioquia. The iPSC cells were thawed and cultivated on matrigel-coated 6 well plates to form colonies. Quality control of iPSCs clones was performed by karyotyping, immunofluorescence, western blotting and spontaneous three-germinal layer differentiation.

2.2. Generation of neural precursor cells (NPCs) and neural differentiation

Generation of NPSCs and Neural differentiation were performed according to Gunhanlar et al. [15] with minor modifications. Human iPSC cells were mechanically detached from matrigel surface. Embryoid bodies (EBs) were generated by transferring iPSCs to non-adherent plates in human embryonic stem cell medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12, 20% knockout serum, 1% minimum essential medium/non-essential amino acid, 1% l-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin on a shaker in an incubator at 37 °C/5% CO2. EBs were grown for 2 days in human embryonic stem cell medium, changed into neural induction medium (DMEM/F12, 1% N2 supplement; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 2 μg/ml, heparin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1% (penicillin/streptomycin) on day 2 and cultured for another 4 days in suspension. For generation of NPCs, the EBs were dissociated by trituration and plated onto laminin-coated 6 well plates in an NPC medium (DMEM/F12, 1% N2 supplement, 2% B27 supplement; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 20 ng/ ml epidermal growth factor and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Once the cells reached 90% of confluence was considered pre-NPCs (passage 1). After passage 5, cells were considered NPCs. Neural differentiation was performed according to ref. [15] with minor modifications. Briefly, the NPCs were plated on laminin-coated sterile coverslips in 12-well plates. NPCs (5000 cm2) were platted in neural differentiation medium (Neural cells-conditioned Neurobasal medium, 1% N2 supplement, 2% B27-RA supplement, 1% minimum essential medium/non-essential amino acid, 20 ng/ ml brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Life technologies), 10 μM Forskolin, 200 μM ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1% (penicillin/ streptomycin) during 20 days. Cells were refreshed with changing a half of medium volume each 5 days.

2.3. Western blots

The iPSCs were detached with 0.25% trypsin and lysed in 50****mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 150****mM sodium chloride, 1.0% Igepal CA-630 (NP-40), and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Fourty μg of proteins was loaded onto 10% or 15% electrophoresis gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-ECL, Amersham Biosciences) at 270 mA for 90 min using an electrophoretic transfer system (BIO-RAD). The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti- OCT4, SOX2, Nanog, KLF4 or CASPASE-3 (cleaved caspase-3 p11 (h176)-R cat# sc-22171-R; Santa Cruz) primary antibodies (1:5000). Anti-actin antibody (cat #MAB1501, Millipore; 1:1000) was used as expression control. Secondary infrared antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IRDye****® 680RD, cat #926-68071; donkey anti-goat IRDye *****® 680RD, cat # 926-68074; and goat anti mouse IRDye ****® 800CW, cat #926-32270; LI-COR Biosciences) 1:10,000 were used for Western blotting analysis and data were acquired by using Odyssey software.

2.4. Immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescent analysis of neural markers, cells were fixed with cold ethanol (−20 °C) for 20 min. followed by triton X-100 (0.1%) permeabilization and 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) blockage. Cells were then incubated overnight with primary antibodies against OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, KLF4, NESTIN, Vimentin and CXCR4 proteins (1:500). After exhaustive rinsing, we incubated the cells with secondary fluorescent antibodies (DyLight 488 and 595 donkey anti-rabbit and -goat and -mouse, cat DI 2488 and DI 1094, respectively) 1:500. The nuclei were stained with 1 μM Hoechst 33342 (life technologies) and images were acquired on a Floyd Cells Imaging Station microscope.

2.5. Analysis of Caspase-3/7 activation by fluorescent inhibitor of caspases (FLICA™) method

The WT and PSEN1 E280 A NLCs (β Tub III positive) cells were fixed with cold ethanol (−20 °C) for 20 min, followed by triton X-100 (0.1%) permeabilization and 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA) blockage. Then cells were incubated overnight with the Vybrant****® FAM Caspase-3 and −7 Assay Kit (Invitrogen, cat # V35118) - FLICA assay. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (1 μM, life technologies). Sections were examined at 200× with a Floyd Cell Imaging Station microscope.

2.6. Image analysis

The images acquired by the Floyd cell imaging station were analyzed by ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). The figures were transformed into 8-bit images and the background was subtracted. The cellular measurement regions of interest (ROI) were drawn around the nucleus (for transcription factors) or over all cells (for cytoplasmic proteins) and the fluorescent intensity was subsequently determined by applying the same threshold for controls and treatments. Mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) was obtained by normalizing total fluorescence in the number of cells.

2.7. Measurement of Aβ1-42 peptide in culture medium

The level of Aβ1-42 peptide was measured according to previous reports with minor modifications [16]. Briefly, NPCs were conditioned with a volume of 1 ml of neural differentiation medium and kept for 20 days. Then after, 100 μl of conditioned medium were collected and the level of secreted Aβ1-42 peptide was determined by a solid phase sandwich ELISA (Invitrogen, Cat# KHB3544) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.8. Acetylcholinesterase release measurement

We determined the acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in supernatants by using the AChE Assay Kit (Abcam, Cat# ab138871) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cell supernatants (see above) were used to perform protein quantification by BCA method (see above) and the detection of AChE activity. AChE degrades the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) into choline and acetic acid. We used the DTNB (5,5′-Dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)) reagent to quantify the thiocholine produced from the hydrolysis of acetylthiocholine by AChE. The absorption intensity of DTNB adduct was used to measure the amount of thiocholine formed, which was proportional to the AChE activity. We read the absorbance in a microplate reader at ****~410 nm. The data obtained were compared to the standard curve values and the AChE amounts (mU) were normalized to protein values (mU/ mg protein).

2.9. Lactate dehydrogenase assay

Cytotoxicity detection kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was used to assess the presence of cytotoxicity by measuring the activity of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released in culture. The culture medium was recovered 20 days after neural differentiation treatment. LDH activity was determined by measuring NADH absorption as the linear rate of consumption during pyruvate reduction to lactate using a spectrophotometer. The LDH released was compared to the amounts of control and was expressed as % of control ± S.D.

2.10. DNA release measurement

Genomic DNA was isolated from 1 ml of the supernatant from differentiating-NPCs after 20 days using Gentra Puregene Blood Kit, cat # 158389. To avoid the impact of the level of fragmentation of DNA on the accuracy of DNA concentration measurement in the supernatant we performed spectrophotometric measurement according to ref. [17] diluted to 1:10 in Tris-EDTA buffer (10****mM Tris, 1****mM ethylenediami-netetraacetic acid, pH 8). Absorbance was measured using the Nano-Drop 2000/2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific). The DNA concentrations were normalized to the amounts of proteins in the supernatant and values for DNA in the media are presented as pg/ μg protein.

2.11. Karyotyping

Karyotype analysis was performed by the Medical Genetics Unit of the Faculty of Medicine, UdeA, using standard cyto-genetic protocols. The iPSCs were incubated with 0.1 mg/ml colcemid (Sigma) for 90 min at 37 °C. Then, cells were detached with 0.25% trypsin and centrifuged at 2300 RPM/20 min. The medium was removed and hypotonic solution (0.075****M KC1, 0.017****M Na-citrate) was added and incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. After a new centrifugation, cells were fixed with freshly prepared Carnoy’s solution. Metaphase spreads were analyzed after staining with quinacrine (Sigma) for karyotyping. Analysis was performed on three different primary cultures counting 20 metaphases for each sample.

2.12. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Student-t analysis calculated with the GraphPad Prism 6 scientific software (GraphPad, Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was accepted at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.001.

3. Results

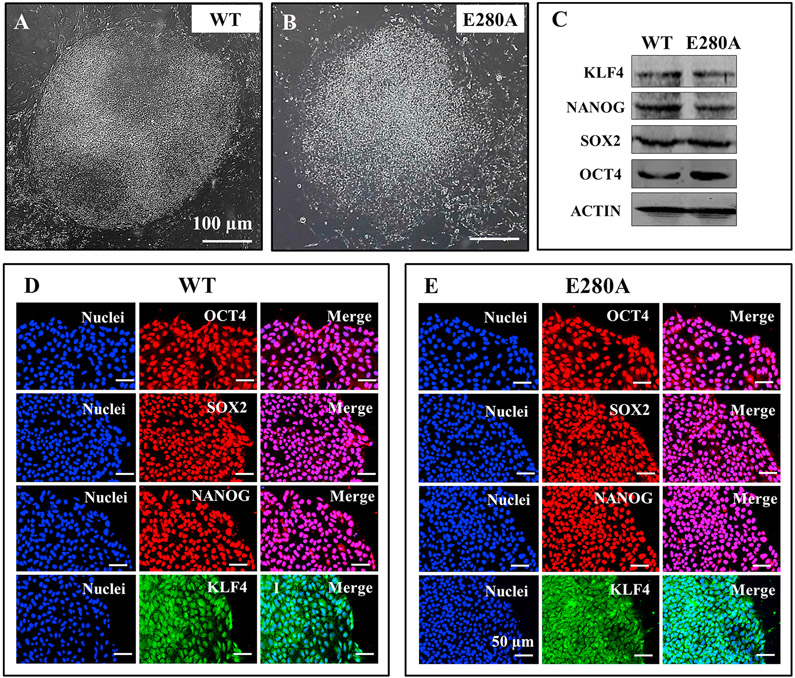

3.1. The iPSCs derived from WT PSEN1 and PSEN1-E280 A fibroblasts have similar expression and potential pluripotency markers

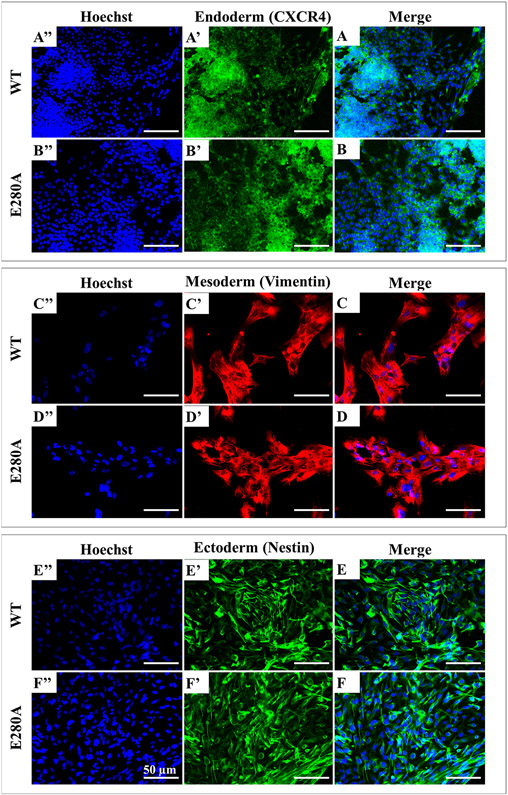

We thawed and cultured control- and patient-specific iPSCs on a matrigel-coated plate with mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells conditioned medium. These cells adopted an iPSC-like morphology and colonies were collected and expanded. Large and stable iPSC colonies were obtained after 15 days of cell thawing (Fig. 1A-B). We investigated the pluripotency of the selected iPSC clones, by analyzing the expression of the endogenous pluripotency marker genes OCT4, SOX2, NANOG and KLF4 by western blotting and immunofluorescence. The pluripotency markers were strongly expressed in the PSEN1-E280 A iPSC clones as well as the WT control (Fig. 1C). Immunofluorescence assays clearly revealed the specific staining of the pluripotency markers OCT4, SOX2, NANOG and KLF4 in iPSC colonies (Fig. 1D and E). We also confirmed the expression of the three germ layer markers (Fig. 2), namely CXCR4 (endoderm; Fig. 2A and B), Vimentin (mesoderm; Fig. 2C and D), and NESTIN (ectoderm; Fig. 2E and F) by immunofluorescence. These observations demonstrate similar pluripotency markers in both WT (control) and PSEN1-E280 A fibroblast derived iPSCs.

Fig. 1. Characterization of wild type and PSEN 1 E280A iPSCs.

(A) Representative light microscopy image of iPSCs colonies formed from a healthy individual; (B) Representative light microscopy image of iPSCs colonies formed from an AD patient carrying PSEN1 E280 A mutation. (C) Representative western blot images of the pluripotency markers KLF4, NANOG, SOX2 and OCT4 in iPSCs; (D–E) Representative immunocytochemistry images of iPSCs stained for OCT4, SOX2, NANOG, and KLF4 in WT (D) and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation (E). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars 50 μm.

Fig. 2. Characterization of wild type and PSEN 1 E280A pluripotency capacity.

(A) Representative immunocytochemistry images of (A, B) endoderm germ layer stained for CXCR4 (green), (C, D) mesoderm stained for Vimentin (red), and (E, F) ectoderm stained for Nestin (green) in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars 50 μm.

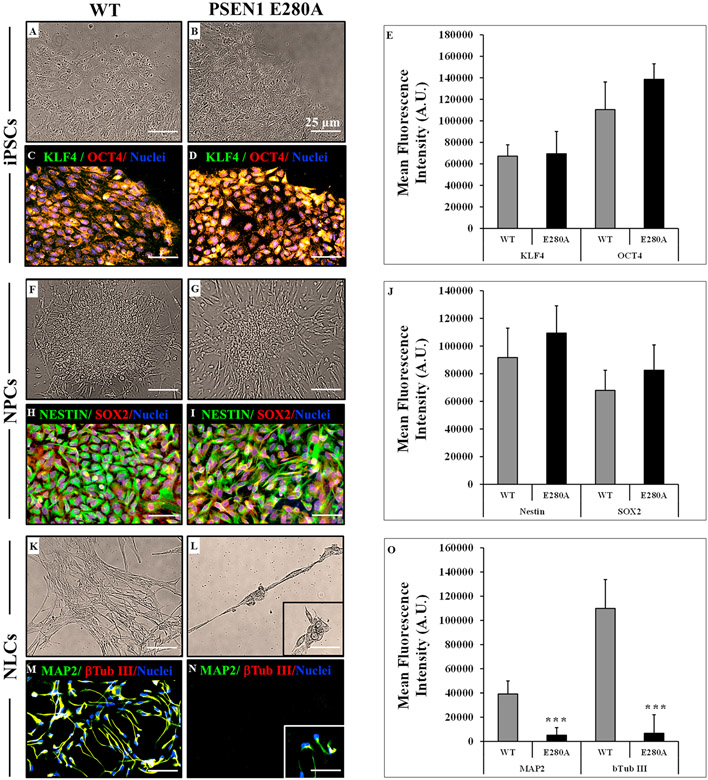

3.2. The iPSCs from WT PSEN1 and the mutant PSEN1 E280 A patient have similar neural precursor cells (NPCs) formation capacity, but PSEN1 E280 A cells failed to differentiate into neurons

We selected flat colonies with smooth edges composed of highly packed cells with large nuclei and a small amount of cytoplasm that expressed KLF4 and OCT4 to perform neural induction (Fig. 3A-E). After neuronal induction, iPSCs became smaller, acquired an elongated bipolar morphology and grew like epithelial colonies fusing to each other (Fig. 3F-G); the iPSC-derived NPCs were positive for NESTIN and preserved SOX2 expression (Fig. 3H-J). To promote neuronal differentiation, NPCs were transferred to differentiation medium. After 20 days, WT PSEN1 NPCs started to change in their shape, displaying early neuronal morphology with long and thin branched extensions, and appeared as nerve-like cells NLCs (Fig 3K) according to the expression of the neuronal markers MAP-2 and β-tubulin III (Fig. 3M and O). However, after 8 days, PSEN1 E280 A NLCs started to die (Fig. 3L) and failed to reach the complete neural differentiation process (Fig. 3N and O).

Fig. 3. The PSEN1 E28A NPCs-derived NLCs fail to complete neural differentiation.

(A) Representative light microscopy image of iPSCs colonies formed from a healthy individual; (B) Representative light microscopy image of iPSCs colonies formed from an AD patient carrying PSEN1 E280 A mutation; (C–D) Representative immunocytochemistry images of fibroblast-derived iPSC stained for KLF4 (green) and OCT (red) in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars 25 μm; (E) Quantification of KLF4 and OCT in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation; (F) Representative light microscopy image of NPCs from a healthy individual; (G) Representative light microscopy image of NPCs formed from an AD patient carrying PSEN1 E280 A mutation; (H-I) Representative immunocytochemistry images of iPSCs-derived NPCs stained for NESTIN (green) and SOX (red) in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation. (J) Quantification of NESTIN and SOX in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation; (K) Representative light microscopy image of NLCs from a healthy individual; (L) Representative light microscopy image of neural-like cells (NLCs) formed from an AD patient carrying PSEN1 E280 A mutation; (M-N) Representative immunocytochemistry images of NPCs-derived NLCs stained for MAP2 (green) and β Tub III (red) in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation. (O) Quantification of MAP2 and β Tub III in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation. Nuclei are stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars 25 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.001.

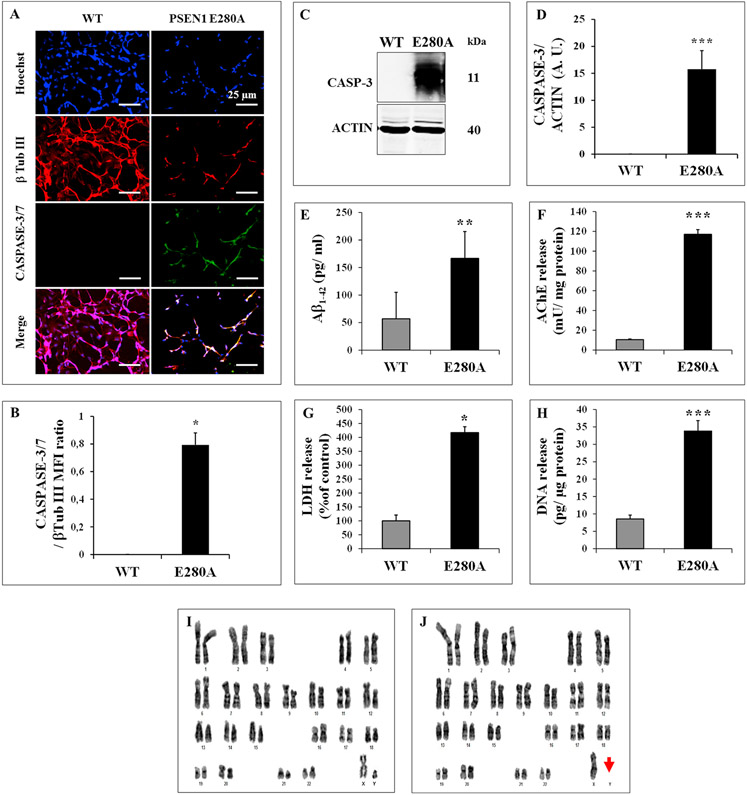

3.3. Mutant PSEN1 E280A differentiated neurons showed activation of CASPASE-3 and produce increased levels of extracellular Aβ1-42

The above observations prompted us to evaluate whether PSEN1 E280 A NLCs would die by apoptosis. To this aim, we evaluated the activation of the executer protease CASPASE-3/7 in both WT and mutant PSEN 1 E280 A NLCs. As shown in Fig. 4, while WT NLCs showed no detectable CASPASE-3/7, the mutant PSEN1 E280 A NLCs displayed extensively positive CASPASE-3/7 immunofluorescent staining (Fig. 4A and B), and positive for CASPASE-3 by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4C and D). In addition, we investigated whether those cells released Aβ1-42 peptide. Previous studies have shown that neurons derived from other familial Alzheimer’s iPSC have a higher susceptibility to Aβ1-42 compared with neurons coming from healthy individuals [11,16]. Therefore, we assessed extracellular levels of Aβ1-42, acetylcholinesterase (AChE), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity and DNA, as indicators of release and/ or cytotoxic Aβ-related effects. As shown in Fig. 4, PSEN1 E280 A NLCs released high amounts of Aβ1-42 (Fig. 4E, 3-fold increase), AChE (Fig. 4F, 11-f. i.), LDH (Fig. 4G, 4-f. i.), and DNA (Fig. 4H, 4-f. i.) compared to healthy WT NLCs (Fig. 4E-H).

Fig. 4. The cytotoxic phenotype of PSEN1-E280 A NLCs is associated with secretion of Aβ1-42 and loss of the Y chromosome.

(A) Representative immunocytochemistry images of NPCs-derived NLCs stained for β Tub III (red) and CASPASE-3/7 in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A mutation; (B) Quantification of CASPASE-3/7; (C) Representative immunoblot of CASPASE-3 in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A NLCs. An antibody against cleaved fragment p11 of CASPASE-3 was used to detect active caspase. Actin was used as an internal control; (D–H) Quantification of CASPASE-3 (D); Aβ1-42 (E), Acetylcholinesterase activity (F), LDH (G) and DNA release (H) in WT and PSEN 1 E280 A NLCs after 20 days of neural differentiation induction. Representative karyotype from unaffected control (I) fibroblast-derived iPSCs showing a normal karyotype (46XY) and karyotype of PSEN1 E280 A patient (J) with the loss of Y chromosome (46X). Data are expressed as mean ± S.D. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.005 and ***p < 0.001.

3.4. Susceptibility of mutant PSEN1-E280 A NLCs to Aβ1-42 is enhanced by the loss of the Y chromosome (LOY)

Several studies have shown that cells without the Y chromosome are at increased risk for all-cause mortality and disease such as Alzheimer’s disease, as well as other conditions in aging men (e.g., ref. [13]). To ascertain if the high susceptibility PSEN1-E280A-NLCs to Aβ1-42 was related to additional genetic alterations, we analyzed the karyotype of iPSCs from WT PSEN1 (control), and PSEN1 E280 A patient. While the karyotype analysis of control performed at passage 68 showed normal set of chromosomes (Fig. 4I), the patient’s karyotype performed at passage 7 showed a chromosomal abnormality (Fig. 4J, red arrow) compatible with LOY chromosome.

4. Discussion

The AD pathology is characterized by synaptic and neuronal degeneration together with accumulation of extracellular plaques composed of Aβ [18]. In terms of molecular pathogenesis, Aβ accumulation can be directly linked to some mutations leading to early onset [4]. However, in the vast majority of cases, i.e. in sporadic AD, the disease may begin with inflammation and the plaques and tangles arise only later as the disease progresses [19]. Thus, multiple co-existing pathologies can further complicate the AD phenotype. Accordingly, here we report for the first time the phenotypic features of a PSEN1 E280 A iPSCs with LOY. This iPSC clone has similar pluripotency characteristics as control cells, including the growth rate and stemness-associated phenotype (i.e., expression of pluripotency markers of the 3 germ layer differentiation). Similarly, AD-derived iPSCs from both sporadic and familial individuals has been cultured and used to further model AD in vitro [20,21]. Indeed, it has been possible to establish iPSC cell lines from AD patients carrying an amyloid precursor protein gene mutation [22]. Taken in conjunction, these studies reveal that the AD-related genotype (i.e. PSEN1 E280 A mutation) or the LOY affects the iPSC derivation nor their transition to NPC.

However, we report the failure of neural differentiation beyond NPCs and massive cell death in PSEN1 E280 A iPSCs clone after 20 days of neural fate induction. The cellular death process determined by the cellular activation of the CASPASE-3, and the release of LDH, AChE and DNA were simultaneously detected with an unceasing generation of the secreted Aβ1-42 peptide. Interestingly, previous reports have shown an enhanced susceptibility to endogenous and exogenous Aβ toxicity in neuronal cultures derived from familial AD associated with a PSEN1 mutation (A246E) after a full differentiation process [16,23]. The disability to complete the differentiation process may be the result of the co-existence of secreted Aβ1-42 with other pathological feature in our PSEN1 E280 A iPSC line. Previously, it was demonstrated that males with AD diagnosis had higher degrees of LOY mosaicism compared to controls [13]. In agreement with this observation, karyotype analysis evidenced the absence of chromosome Y in PSEN1 E280 A iPSCs compared to WT PSEN1 iPSCs. Therefore, our results suggest that LOY might participate as an AD risk factor during aging by enhancing the process related to uncontrolled and massive neuronal cell death. Moreover, these findings also suggest that LOY should be associated with concomitant genetic mutations or metabolic dysfunctions to enhance the AD phenotype as we have shown in vitro. Further investigations are however required to fully establish the role of LOY in FAD patients. In line with this, Zuo and co-workers have developed a new CRISPR-CAS9 methodology to induce a Y chromosome depletion in ESCs [24]. This new methodological approach may be used to establish new iPSC and/or neural precursor cell lines derived from patients aiming to determine the effect in vitro of LOY in ageing people with other risk factors or genetic alterations leading to AD development.

5. Conclusions

It is concluded that AD differentiated neurons with LOY, particularly those from a PSEN1 E280 A carrier, are highly sensitive to the toxic effects of its intrinsic Aβ1-42 generation, leading to impaired neural differentiation. Thus, this work points to a possible role of LOY in AD patients to better understand the physiological characteristics of this risk factor and its application to the design of strategies that might retard AD pathology and symptoms in ageing men with mosaicism or LOY chromosome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Colciencias grant #1115-657-40786, contract #623-2014 to MJ-Del-Rio and CV-P. MM-P is enrolled as a post-Doctoral fellowship grant #784-2017 from Colciencias. We would like to express our gratitude to I. Hernandez for iPSC preparation from University of California, Santa Barbara; CA Villegas-Lanau, F Piedrahita and L. Madrigal for skin biopsy from FAD PSEN 1 patient, and to the Genetics Medical Unit of the Faculty of Medicine for their help in the karyotype analysis.

References

- [1].Douchamps V, Mathis C, A second wind for the cholinergic system in Alzheimer’s therapy, Behav. Pharmacol 28 (2 and 3-Spec Issue) (2017) 112–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bloom GS, Amyloid-beta and tau: the trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis, JAMA Neurol. 71 (4) (2014) 505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Van Cauwenberghe C, Van Broeckhoven C, Sleegers K, The genetic landscape of Alzheimer disease: clinical implications and perspectives, Genet. Med 18 (5) (2016) 421–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lopera F, Ardilla A, Martínez A, Madrigal L, Arango-Viana JC, Lemere CA, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Hincapíe L, Arcos-Burgos M, Ossa JE, Behrens IM, Norton J, Lendon C, Goate AM, Ruiz-Linares A, Rosselli M, Kosik KS, Clinical features of early-onset Alzheimer disease in a large kindred with an E280A presenilin-1 mutation, JAMA 277 (10) (1997) 793–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fleisher AS, Chen K, Quiroz YT, Jakimovich LJ, Gomez MG, Langois CM, Langbaum JB, Ayutyanont N, Roontiva A, Thiyyagura P, Lee W, Mo H, Lopez L, Moreno S, Acosta-Baena N, Giraldo M, Garcia G, Reiman RA, Huentelman MJ, Kosik KS, Tariot PN, Lopera F, Reiman EM, Florbetapir PET analysis of amyloid-beta deposition in the presenilin 1 E280A autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease kindred: a cross-sectional study, Lancet Neurol. 11 (12) (2012) 1057–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Quiroz YT, Sperling RA, Norton DJ, Baena A, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Cosio D, Schultz A, Lapoint M, Guzman-Velez E, Miller JB, Kim LA, Chen K, Tariot PN, Lopera F, Reiman EM, Johnson KA, Association between amyloid and tau accumulation in young adults with autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease, JAMA Neurol. 75 (5) (2018) 548–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Okita K, Yamanaka S, Induction of pluripotency by defined factors, Exp. Cell Res 316 (16) (2010) 2565–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Takahashi K, Yamanaka S, Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors, Cell 126 (4) (2006) 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Imaizumi Y, Okano H, Modeling human neurological disorders with induced pluripotent stem cells, J. Neurochem 129 (3) (2014) 388–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Goldstein LS, Reyna S, Woodruff G, Probing the secrets of Alzheimer’s disease using human-induced pluripotent stem cell technology, Neurotherapeutics 12 (1) (2015) 121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Oksanen M, Petersen AJ, Naumenko N, Puttonen K, Lehtonen Š, Gubert Olivé M, Shakirzyanova A, Leskelä S, Sarajärvi T, Viitanen M, Rinne JO, Hiltunen M, Haapasalo A, Giniatullin R, Tavi P, Zhang SC, Kanninen KM, Hämäläinen RH, Koistinaho J, PSEN1 Mutant iPSC-derived model reveals severe astrocyte pathology in Alzheimer’s disease, Stem Cell Rep. 9 (6) (2017) 1885–1897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ochalek A, Mihalik B, Avci HX, Chandrasekaran A, Téglási A, Bock I, Giudice ML, Táncos Z, Molnár K, László L, et al. , Neurons derived from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease iPSCs reveal elevated TAU hyperphosphorylation, increased amyloid levels, and GSK3B activation, Alzheimers Res. Ther 9 (2017) 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dumanski JP, Lambert JC, Rasi C, Giedraitis V, Davies H, Grenier-Boley B, Lindgren CM, Campion D, Dufouil C, Pasquier F, Amouyel P, Lannfelt L, Ingelsson M, Kilander L, Lind L, Forsberg LA, Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in blood is associated with Alzheimer disease, Am. J. Hum. Genet 98 (6) (2016) 1208–1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fong H, Wang C, Knoferle J, Walker D, Balestra ME, Tong LM, Leung L, Ring KL, Seeley WW, Karydas A, Kshirsagar MA, Boxer AL, Kosik KS, Miller AL, Huang Y, Genetic correction of tauopathy phenotypes in neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells, Stem Cell Rep. 1 (3) (2013) 226–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gunhanlar N, Shpak G, van der Kroeg M, Grouty-Colomer LA, Munshi ST, Lendemeijer B, Ghazvini M, Dupont C, Hoogendijk WJG, Gribnau J, de Vrij FMS, Kushner SA, A simplified protocol for differentiation of electrophysiologically mature neuronal networks from human induced pluripotent stem cells, Mol. Psychiatry 23 (5) (2018) 1336–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Armijo E, Gonzalez C, Shahnawaz M, Flores A, Davis B, Soto C, Increased susceptibility to Abeta toxicity in neuronal cultures derived from familial Alzheimer’s disease (PSEN1-A246E) induced pluripotent stem cells, Neurosci. Lett 639 (2017) 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sedlackova T, Repiska G, Celec P, Szemes T, Minarik G, Fragmentation of DNA affects the accuracy of the DNA quantitation by the commonly used methods, Biol. Proced. Online 15 (1) (2013) 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K, Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 82 (12) (1985) 4245–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Krstic D, Knuesel I, Deciphering the mechanism underlying late-onset Alzheimer disease, Nat. Rev. Neurol 9 (1) (2013) 25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moreno CL, Della Guardia L, Shnyder V, Ortiz-Virumbrales M, Kruglikov I, Zhang B, Schadt EE, Tanzi RE, Noggle S, Buettner C, Gandy S, iPSC-derived familial Alzheimer’s PSEN2 (N141I) cholinergic neurons exhibit mutation-dependent molecular pathology corrected by insulin signaling, Mol. Neurodegener 13 (1) (2018) 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ochalek A, Mihalik B, Avci HX, Chandrasekaran A, Teglasi A, Bock I, Giudice ML, Tancos Z, Molnar K, Laszlo L, Nielsen JE, Holst B, Freude K, Hyttel P, Kobolak J, Dinnyes A, Neurons derived from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease iPSCs reveal elevated TAU hyperphosphorylation, increased amyloid levels, and GSK3B activation, Alzheimers Res. Ther 9 (1) (2017) 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang Z, Zhang P, Wang Y, Shi C, Jing N, Sun H, Yang J, Liu Y, Wen X, Zhang J, Zhang S, Xu Y, Establishment of induced pluripotent stem cell line (ZZUi010-A) from an Alzheimer’s disease patient carrying an APP gene mutation, Stem Cell Res. 25 (2017) 213–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mahairaki V, Ryu J, Peters A, Chang Q, Li T, Park TS, Burridge PW, Talbot BC Jr., Asnaghi L, Martin LJ, Zambidis ET, Koliatsos VE, Induced pluripotent stem cells from familial Alzheimer’s disease patients differentiate into mature neurons with amyloidogenic properties, Stem Cells Dev. 23 (24) (2014) 2996–3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zuo E, Huo X, Yao X, Hu X, Sun Y, Yin J, He B, Wang X, Shi L, Ping J, Wei Y, Ying W, Wei W, Liu W, Tang C, Li Y, Hu J, Yang H, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted chromosome elimination, Genome Biol. 18 (1) (2017) 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]