In the original article, there were mistakes in Tables 1 and 2, and Figure 2 as published. Instead of the accession ATCC 19443 for the type strain of E. faecalis, it should read ATCC 19433 in Tables 1 and 2, and Figure 2, as well as throughout the text (in MATERIALS AND METHODS, section Bacterial Strains, 1st paragraph and section Analysis of Bacterial Tolerance to Drug, 1st paragraph; in RESULTS, section Cinnamaldehyde Inhibits the Growth of S. aureus and E. faecalis without Inducing an Adaptive Phenotype, 3rd paragraph, section Cinnamaldehyde Sub-inhibitory Concentrations Decrease the Ability of S. aureus to Adhere to Latex, 1st paragraph; and in the DISCUSSION, section Cinnamaldehyde Inhibits the Growth of S. aureus and E. faecalis without Inducing an Adaptive Phenotype, 1st paragraph, section Cinnamaldehyde Sub-inhibitory Concentrations Decrease the Ability of S. aureus to Adhere to Latex, 1st paragraph).

Table 1.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus strains.

| Strain | Antibiotic | MAR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN | VAN | OXA | GEN | CLI | CIP | SUT | ||

| E. faecalis ATCC 19433 | S | S | – | S | – | S | – | 0 |

| E. faecalis 1 | S | S | – | S | – | S | – | 0 |

| E. faecalis 2 | R | S | – | S | – | S | – | 0.25 |

| E. faecalis 3 | R | S | – | R | – | R | – | 0.75 |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | 0 |

| S. aureus ATCC 6538 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | 0 |

| S. aureus 1 | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | 0 |

| S. aureus 2 | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 3 | R | S | R | S | R | S | R | 0.50 |

| S. aureus 4 | R | S | R | S | R | S | S | 0.43 |

Experiments were performed three times in duplicate.

PEN, Penicillin; VAN, vancomycin; OXA, oxacillin; GEN, gentamicin; CLI, clindamycin, CIP, ciprofloxacin; SUT, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim. Multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial activity of cinnamaldehyde against Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis.

| Strain | MIC1 | MBC2 |

|---|---|---|

| E. faecalis ATCC 19433 | 0.25 | 1 |

| E. faecalis 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| E. faecalis 2 | 0.25 | 1 |

| E. faecalis 3 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 0.5 | 1 |

| S. aureus ATCC 6538 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 1 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 2 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 3 | 0.25 | 1 |

| S. aureus 4 | 0.25 | 1 |

Experiments were performed three times in duplicate.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and

Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) are expressed in mg/ml.

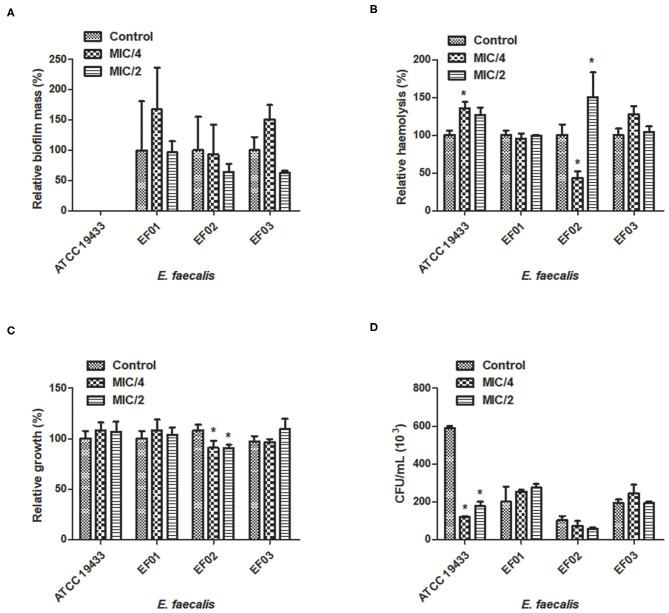

Figure 2.

Effect of cinnamaldehyde (MIC/2 and MIC/4) on virulence factors of Enterococcus faecalis strains. (A) Biofilm mass production; (B) Haemolytic activity; (C) Serum resistance; (D) Adhesion to latex (catheter). *p < 0.05, compared with vehicle-treated controls. Experiments were performed three times in duplicate. Each bar represents mean ± SD.

In the original article, there was an error. All instances of E. faecalis ATCC 19443 should read ATCC 19433.

Corrections has been made to the following sections:

MATERIALS AND METHODS, Bacterial Strains, 1st paragraph:

All tested bacteria were kindly provided by the bacterial collection sector of the Universidade CEUMA and included: six strains of S. aureus (standard strains ATCC 25923 and ATCC 6538; clinical isolates SA01, SA02, SA03, SA04); four strains of E. faecalis (standard strain ATCC 19433; clinical isolates EF01, EF02, EF03). Susceptibility to antimicrobials was determined in an automated VITEK® 2 system (BioMérieux Clinical Diagnostics, USA) and data interpretation was performed as recommended by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (2015). The multiple antibiotic resistance (MAR) index was calculated using the formula MAR = x/y, where “x” was the number of antibiotics to which the isolate demonstrated resistance; and “y” was the total number of antibiotics tested. The antibiotic susceptibility profile of each strain is shown at Table 1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS, Analysis of Bacterial Tolerance to Drug, 1st paragraph:

In order to investigate whether cinnamaldehyde is able to induce bacterial tolerance to drug, we performed serial passage experiments, using the standard strains of S. aureus (ATCC 25923) and E. faecalis (ATCC 19433). For this, bacterial suspensions (1 ml, ~1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) were added to six-well tissue culture plates containing MH broth and sub-inhibitory concentrations (MIC/2) of cinnamaldehyde or ciprofloxacin (positive control). After 24 h at 37°C, the culture growing at one dilution below the MIC was used to inoculate the subsequent passage, and this process was repeated for a total of 10 passages. The compound concentration range of each new passage was based on the MIC calculated for the previous passage. Vehicle-treated bacteria (2% DMSO in PBS) were used as negative controls.

RESULTS, Cinnamaldehyde Inhibits the Growth of S. aureus and E. faecalis without Inducing an Adaptive Phenotype, 3rd paragraph:

Additionally, when incubated in vitro with cinnamaldehyde, neither S. aureus (ATCC 25923) nor E. faecalis (ATCC 19433) developed adaptive phenotypes even after 10 sequential passages. In contrast, both strains became tolerant to the clinically used antibiotic ciprofloxacin as MIC values increased from 0.0625 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml for S. aureus, and from 0.125 μg/ml to 0.5 μg/ml for E. faecalis.

RESULTS, Cinnamaldehyde Sub-inhibitory Concentrations Decrease the Ability of S. aureus to Adhere to Latex, 1st paragraph:

We also evaluated whether the sub-inhibitory concentrations of cinnamaldehyde were able to affect bacterial adhesion to latex, using a catheter model. As expected, all tested S. aureus and E. faecalis strains were able to adhere to latex. The sub-inhibitory concentrations of cinnamaldehyde were able to reduce the adherence to latex by all tested S. aureus strains (Figure 1D). When tested at MIC/2, cinnamaldehyde maximum inhibitory effects were observed for S. aureus ATCC 25923 (94.2%), and the clinical isolates SA03 (93.1%) and SA01 (91.3%). Also importantly, the same concentration of cinnamaldehyde diminished latex adhesion by S. aureus ATCC 6538 (67.4%), SA04 (59.6%), and SA02 (48.7%). The adhesion of S. aureus ATCC 25923 was also the most reduced by cinnamaldehyde at MIC/4 (93.0%), followed by SA01 (79.6%), SA03 (69.0%), SA02 (58.6%), SA04 (46.7%), and SA01 (44.7%). On the other hand, this compound only affected the adherence to latex of E. faecalis ATCC 19433 with reductions of 79.7 and 69.8% by cinnamaldehyde at MIC/2 and MIC/4, respectively (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION, Cinnamaldehyde Inhibits the Growth of S. aureus and E. faecalis without Inducing an Adaptive Phenotype, 1st paragraph:

Cinnamaldehyde presented with antimicrobial actions on clinical isolates of S. aureus and E. faecalis, in addition to ATCC standard strains. This compound was effective on all strains of E. faecalis and S. aureus, including those with a multidrug resistance phenotype. The antimicrobial properties of cinnamaldehyde have been demonstrated against a range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens including S. aureus and E. faecalis (Cox and Markham, 2007; Shen et al., 2015; Upadhyay and Venkitanarayanan, 2016). Cinnamaldehyde actions against these pathogens are related to changes in their cell membrane polarity and permeability (Hammer and Heel, 2012). Importantly, we show for the first time that although becoming tolerant to ciprofloxacin, neither S. aureus (ATCC 25923) or E. faecalis (ATCC 19433) develop an adaptive phenotype when incubated with cinnamaldehyde in vitro.

DISCUSSION, Cinnamaldehyde Sub-inhibitory Concentrations Decrease the Ability of S. aureus to Adhere to Latex, 1st paragraph:

Catheterization is a potential risk factor for bacterial colonization and infection (Padmavathy et al., 2015; Tong et al., 2015). S. aureus and E. faecalis are both capable of adhering to abiotic surfaces (such as catheter) due to the expression of surface proteins (Foster et al., 2014), such as the S. aureus protein A (SpA) and the enterococcal surface protein (Esp) (Elhadidy and Elsayyad, 2013; Zapotoczna et al., 2016). Cinnamaldehyde strongly inhibited S. aureus adherence to latex, an effect that was observed when this compound was tested at MIC/2 and MIC/4 on all strains. When tested on E. faecalis strains, cinnamaldehyde only diminished latex adherence by the standard strain ATCC 19433.

The authors apologize for these errors and state that this does not change the scientific conclusions of the article in any way. The original article has been updated.

References

- Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI] (2015). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Fifth Informational Supplement. Wayne PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 1–240. [Google Scholar]

- Cox S. D., Markham J. L. (2007). Susceptibility and intrinsic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to selected plant volatile compounds. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 930–936. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadidy M., Elsayyad A. J. (2013). Uncommitted role of enterococcal surface protein, Esp, and origin of isolates on biofilm production by Enterococcus faecalis isolated from bovine mastitis. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 46, 80–84. 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster T. J., Geoghegan J. A., Ganesh V. K., Höök M. (2014). Adhesion, invasion and evasion: the many functions of the surface proteins of Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 49–62. 10.1038/nrmicro3161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer K. A., Heel K. A. (2012). Use of multiparameter flow cytometry to determine the effects of monoterpenoids and phenylpropanoids on membrane polarity and permeability in staphylococci and enterococci. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 40, 239–245. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmavathy K., Praveen S., Madhavan R., Krithika N., Kiruthiga A. J. (2015). Clinico-microbiological investigation of catheter associated urinary tract infection by Enterococcus faecalis: vanA genotype. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9, DD05–DD6. 10.7860/JCDR/2015/13856.6378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen S., Zhang T., Yuan Y., Lin S., Xu J., Ye H. (2015). Effects of cinnamaldehyde on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus membrane. Food Control. 47, 196–202. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong S. Y., Davis J. S., Eichenberger E., Holland T. L., Fowler V. G. (2015). Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 603–661. 10.1128/CMR.00134-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A., Venkitanarayanan K. (2016). In vivo efficacy of trans-cinnamaldehyde, carvacrol, and thymol in attenuating Listeria monocytogenes infection in a Galleria mellonella model. J. Nat. Med. 70, 667–672. 10.1007/s11418-016-0990-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapotoczna M., O'Neill E., O'Gara J. P. (2016). Untangling the diverse and redundant mechanisms of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005671. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]