Summary box.

Promoting respect at interpersonal and health system levels attract more women to health facilities, improves their childbirth experiences and mitigate preventable deaths, thereby bridging maternal health inequities.

Addressing maternal mortality from a rights-based approach is exercising leadership up to the expectations of women’s rights to live and enjoy quality, culturally sensitive and respectful health services.

The scale of respectful maternity care extends beyond the interpersonal facets of care in health facilities and spans meso-level and macro-level health system elements.

Respectful maternity care has its foundations on a robust health system, and you cannot have respectful care in the absence of a well-functioning health system.

The World Health Organization describes respectful maternity care (RMC) as “the care organised for and provided to all women in a manner that maintains their dignity, privacy and confidentiality, ensures freedom from harm and mistreatment, and enables informed choice and continuous support during labour and childbirth”.1

The components of respectful care mentioned in the definition above focus on the interpersonal relationships in the woman–provider dyad. Nonetheless, they have their foundations on a robust health system, and respectful care cannot be realised in the absence of a well-functioning health system.

In this commentary, I will focus on the potential of promoting RMC—from the perspectives of health system strengthening—in bridging the gap in maternal health inequity. I use evidence from Ethiopia to elaborate the cases where necessary and share my thoughts on the way forward to promote RMC, especially in low-income settings.

Maternal mortality has declined worldwide, with an impressive 45.2% reduction between 1990 and 2017.2 However, there is a staggering divide between low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and high-income countries, the former accounting for 99% of global maternal deaths in 2017. Sub-Saharan Africa is home to 66% of the global maternal deaths in the same year.2 Additionally, the majority of maternal deaths occur in countries whose health systems are inadequately financed, leading to poor availability, accessibility, quality, and thereby low utilisation of life-saving maternal health services.2 In the positive side, in low-income countries, increase in maternal health investment significantly contributes to the reduction of maternal mortality;3 this warrants the existence of a window of opportunity to improve maternal health if there is a strong political commitment.

The high maternal mortality in LMICs also indicates the existential gap in meeting women’s right to freedom of choice and access to a well-functioning health system.4 In sub-Saharan Africa, constellations of rights-related individual and systems-level factors, including the mistreatment of women, act as powerful barriers to the utilisation of life-saving maternal health services.5 6 Despite being a growing body of scholarship, studies from Ethiopia and globally have shown a worrisome occurrence and manifestations of the mistreatment of childbearing women in health facilities.7–10

Scholars suggest framing maternal mortality from the perspective of fundamental human rights to foster accountability in the move to ending preventable maternal deaths.11 12 Eventually, the human rights approach to maternal health marked the juncture of RMC as the Universal Rights of Childbearing Women which evolved under the leadership of the White Ribbon Alliance.13 WHO’s Strategies Toward Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality that were introduced in 2015 calls for health systems not to neglect RMC while endeavouring to deliver effective clinical interventions.14

RMC from the perspectives of people-centred healthcare

Meeting people’s legitimate right to and expectations for equitable and respectful care, including respecting social preferences, is the cornerstone of people-centred healthcare.15 16 Through the lens of people-centred care, RMC is not only a human rights issue, it is also an issue of gender equity.17 On the 69th World Health Assembly, the executive board passed a resolution to integrate the concept of people-centred health services into health systems, which has amplified the focus given to RMC.16 In a panorama, the scale of RMC extends beyond the interpersonal facets of care in health facilities and spans meso-level and macro-level health system elements. Likewise, mistreatment or the failure to provide RMC do not predominantly originate from health professionals’ behaviour but from health system constraints, where actions need to be concerted.7 18

How can RMC be promoted?

Globally, there is a dearth of evidence on the efficacy of RMC interventions and innovative approaches that can mitigate these constraints and thereby lessen the mistreatment of childbearing women in health facilities.

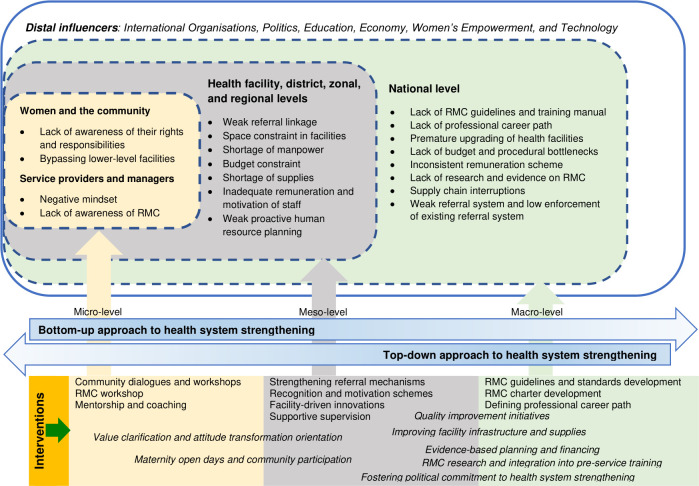

Here, I am largely drawing from an implementation research from Ethiopia that explored health system constraints to the promotion of RMC in public hospitals and tested a multicomponent intervention (staff training, placement of wall posters and post-training onsite support for quality improvement) that was designed to promote RMC.18–20 The study used an interventional mixed methods design that included surveys of both women and service providers before and after the intervention, focus group discussions with service providers before and after the intervention and in-depth interviews with key informants before the intervention. Based on the findings of the study and other implementation studies from Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania,21–23 I have synthesised approaches to the promotion of RMC (figure 1). In figure 1, identified barriers to the promotion of RMC in Ethiopian hospitals are organised across micro-level, meso-level and macro-levels of the health system.

Figure 1.

Health system strengthening approaches to the promotion of RMC.

Likewise, interventions that were tested to promote RMC in various settings globally are also categorised under their respective health system level, some having the potential to operate in more than one level. Interventions at the individual (women, communities and service providers) level largely focus on behavioural interventions while meso-level interventions target filling gaps at lower and middle-level facilities; macro-level actions concentrate on policies, strategies and guidelines to improve the operation of health systems.

Given the complex relationships between different elements described in figure 1,18 RMC interventions targeting a specific component cannot have a lasting effect. In lieu, system-oriented and multidimensional interventions are warranted to improve the accessibility and uptake of maternity care and march towards a rights-based approach to ending maternal mortality. Taking into account the interpersonal and system-level nature of RMC and the wide array drivers of mistreatment,24 it is commendable to implement bottom-up and top-down health system strengthening to promote RMC (figure 1).

COVID-19 and RMC

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are exacerbating maternal health inequities globally; in low-income settings, the impacts are higher due to pre-existing weak health systems. The pandemic is adversely affecting maternal health services in various aspects through disrupting the supply chain of essential supplies and logistics, diverting attention away from maternal health, interrupting the availability of antenatal and childbirth services, reducing maternal healthcare seeking among women due to the fear of getting infected, inappropriate separation of mothers and newborns and reduced interpersonal care to minimise contact between clients and service providers.25 26

Evidence generated during and after the pandemic significantly contribute to actions to be taken to ensuring health system resilience in the long run and making the health system ready for the next crisis.27 As such, future health system strengthening initiatives should amalgamate strategies to absorb shocks and maintain the quality and respectfulness of maternity care. In the absence of resilience, struggling and fragile health systems further deteriorate and would lead to devastatingly increased levels of maternal and child mortalities from preventable causes, let alone maintaining RMC specifically and quality of care generally.25 28

The way forward

Because RMC is a cross-cutting issue, its advocacy and promotion should engage a range of stakeholders, including health workers, women, communities, policymakers and implementing institutions.29 Women and the community at large should be well-oriented about women’s rights in the maternal health continuum as this will play a significant role in the enforcement of the law to protect women’s rights. On the other hand, in addition to designing evidence-oriented strategies to strengthen the various health system functions, the meso-level and macro-level health system actors should articulate the tenets of RMC as part of their core values and work towards the institutionalisation of RMC standards and strengthening accountability mechanisms in service delivery outlets.30 31

Rights-based approach to respectful care

Governments along with their allies should design and/or enforce system-wide policies and strategies that foster the inalienable rights of childbearing women to the access to high quality and respectful care; this includes financial accountability to ensure that no woman is left behind. Furthermore, nurturing a culture of accountability and respect in healthcare plays paramount importance to curb the intentional mistreatment and humiliation of women in health facilities.32

Decolonising research on RMC and building local capacity

RMC includes respecting women’s unharmful cultural preferences. I believe that researchers endowed with local and cultural understandings are well-posited to delve into the cultural fabrics in their community to explore and address cultural barriers to the utilisation of maternal health services. However, as it is with other health research, research on maternal health services—including RMC—is meagre and largely masterminded by international researchers, local researchers often playing ancillary roles when involved. Therefore, working towards investing in implementation research and building local research capacity yields strong evidence which can be translated into practice. In accordance with Abimbola’s ‘gaze-pose matrix’, bulging the ‘ideal’ matrix would accelerate knowledge translation for the betterment of RMC at local levels.33 With such a mindset, improving local and international funding for implementation research on RMC would be commendable to design, test and scale-up high-yield interventions.

Conclusion

Addressing maternal mortality from a rights-based approach is exercising leadership up to the expectations of women’s rights to live and enjoy quality, culturally sensitive and respectful health services. To hasten the ever-prevailing maternal health inequities globally and nationally, acting on the missing link—RMC—from the perspectives of health system strengthening helps not only to improve maternal health services and meet the maternal mortality target of the sustainable development goals, it also augments the progress to achieving universal health coverage.

Moreover, promoting respect at interpersonal and health system levels attract more women to health facilities, improves their childbirth experiences and mitigate preventable deaths. RMC is not only about dealing with ‘women’s issues’; it is also about creating healthier families, communities and nations.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @AntenehAsef

Contributors: I am the sole author of the commentary.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Who recommendations: intrapartum care for a positive childbirth experience. World Health Organization, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization Trends in maternal mortality: 2000 to 2017: estimates by who, UNICEF, UNFPA, world bank group and the United nations population division. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nuhu KM, McDaniel JT, Alorbi GA, et al. Effect of healthcare spending on the relationship between the human development index and maternal and neonatal mortality. Int Health 2018;10:33–9. 10.1093/inthealth/ihx053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.United Nations Maternal mortality and morbidity and human rights. Human Rights Office of the Commissioner, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyei-Nimakoh M, Carolan-Olah M, McCann TV. Access barriers to obstetric care at health facilities in sub-Saharan Africa-a systematic review. Syst Rev 2017;6:110. 10.1186/s13643-017-0503-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moyer CA, Mustafa A. Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health 2013;10:40. 10.1186/1742-4755-10-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med 2015;12:e1001847. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asefa A, Bekele D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. reproductive health. 12, 2015: 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asefa A, Bekele D, Morgan A, et al. Service providers' experiences of disrespectful and abusive behavior towards women during facility based childbirth in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2018;15:4. 10.1186/s12978-017-0449-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheferaw ED, Kim Y-M, van den Akker T, et al. Mistreatment of women in public health facilities of Ethiopia. Reprod Health 2019;16:130. 10.1186/s12978-019-0781-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batist J. An intersectional analysis of maternal mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: a human rights issue. J Glob Health 2019;9:010320. 10.7189/jogh.09.010320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bueno de Mesquita J, Kismödi E. Maternal mortality and human rights: landmark decision by United nations human rights body. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:79–79A. 10.2471/BLT.11.101410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alliance WR. Respectful maternity care: the universal rights of childbearing women. Washington (District of Columbia: White Ribbon Alliance, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.ten Hoope-Bender P, de Bernis L, Campbell J, et al. Improvement of maternal and newborn health through midwifery. Lancet 2014;384:1226–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60930-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Sixty-Ninth World health assembly: framework on integrated, people-centred health services. Contract No: A69/39. World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sreenivas A, Cohen S, Magaña-Valladares L, et al. Humanized childbirth and cultural humility: designing an online course for maternal health providers in Limited-Resource settings. Int J Childbirth 2015;5:188–99. 10.1891/2156-5287.5.4.188 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asefa A, McPake B, Langer A, et al. Imagining maternity care as a complex adaptive system: understanding health system constraints to the promotion of respectful maternity care.. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 2020;28:1–19. 10.1080/26410397.2020.1854153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asefa A, Morgan A, Bohren MA, et al. Lessons learned through respectful maternity care training and its implementation in Ethiopia: an interventional mixed methods study. Reprod Health 2020;17:103. 10.1186/s12978-020-00953-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asefa A, Morgan A, Gebremedhin S, et al. Mitigating the mistreatment of childbearing women: evaluation of respectful maternity care intervention in Ethiopian hospitals. BMJ Open 2020;10:e038871. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abuya T, Ndwiga C, Ritter J, et al. The effect of a multi-component intervention on disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:224. 10.1186/s12884-015-0645-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kujawski SA, Freedman LP, Ramsey K, et al. Community and health system intervention to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanga region, Tanzania: a comparative before-and-after study. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002341. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ratcliffe HL, Sando D, Lyatuu GW, et al. Mitigating disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanzania: an exploratory study of the effects of two facility-based interventions in a large public hospital. Reprod Health 2016;13:79. 10.1186/s12978-016-0187-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sen G, Reddy B, Iyer A. Beyond measurement: the drivers of disrespect and abuse in obstetric care. Reprod Health Matters 2018;26:6–18. 10.1080/09688080.2018.1508173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley T, Sully E, Ahmed Z, et al. Estimates of the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2020;46:73–6. 10.1363/46e9020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Busch-Hallen J, Walters D, Rowe S, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and child health. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1257. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30327-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, et al. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet 2015;385:1910–2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e901–8. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30229-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogel JP, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ӧ, et al. Promoting respect and preventing mistreatment during childbirth. BJOG 2016;123:671–4. 10.1111/1471-0528.13750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McConville B. Respectful maternity care--how the UK is learning from the developing world. Midwifery 2014;30:154–7. 10.1016/j.midw.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Windau-Melmer T. A guide for Advocating for Respectful maternity care. Washington, DC: Futures Group, Health Policy Project, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zampas C, Amin A, O'Hanlon L. Operationalizing a human Rights-Based approach to address mistreatment against women during childbirth. Health Hum Rights 2020;22:251–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abimbola S. The foreign gaze: authorship in academic global health. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e002068. 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-002068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]