Abstract

We report an interesting case of a 38-year-old woman presenting with reverse Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) secondary to an Addisonian crisis, her second such episode. A few years prior, she had presented with typical TTS in the setting of Addisonian crisis; diagnostic work-up revealing Auto-Immune Polyglandular Syndrome Type II (APS II). We believe this to be the first case report of typical and variant phenotypes of TTS in a patient with APS II. The pathogenic link between these two conditions is explored. In patients presenting with Addisonian crises and refractory shock, the possibility of concurrent TTS should be considered. TTS muddies the diagnostic waters and poses therapeutic challenges as outlined.

Keywords: cardiovascular medicine, heart failure, interventional cardiology, clinical diagnostic tests, adrenal disorders

Background

The concurrent diagnoses of Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) and Auto-Immune Polyglandular Syndrome Type II (APS II) in the same patient is a very rare but challenging entity. APS II is an autoimmune condition that includes a diagnosis of Addison’s disease plus either an autoimmune thyroid disease and/or type one diabetes mellitus.1 The defining endocrine disorder in Addison’s disease is an inability to produce vital hormones namely cortisol and aldosterone; acute deficiencies of which may manifest as refractory life-threatening shock syndrome. TTS is typically seen in postmenopausal women.2 They present in approximately 2% of all troponin-positive cases and are commonly mistaken as an acute coronary syndrome. However, no evidence of acute plaque rupture is documented during angiography. Full blown TTS may also present with cardiogenic shock that may be life-threatening. We report a unique presentation of two variants of TTS as initial manifestations of consecutive Addisonian crises in the same patient. Differential diagnoses are explored, diagnostic criteria for TTS are underlined and therapeutic specifics of shock syndrome in this double jeopardy scenario are emphasised.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old female patient presented to her local hospital with general weakness, abdominal pain, haemodynamic instability (initial blood pressure of 66/40 mm Hg) and altered sensorium with a reduced Glasgow Coma Scale of 8/15. At home hospital, she was promptly resuscitated with boluses of normal saline and ringer’s lactate. Inotropes were started and the patient was intubated due to acute hypoxemic respiratory failure with tachypnoea (respiratory rate 55 breaths/min), oxygen saturations <80% on high flow oxygen of 10 L/min and altered level of consciousness with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 8/15. After initial stabilisation, she was transferred to the tertiary intensive care unit. Her haemodynamics had improved and the patient had been extubated. However, the patient deteriorated rapidly postextubation, failing non-invasive ventilation and requiring reintubation. She was then transferred to our tertiary coronary care unit for further management. She was infusing norepinephrine at 0.14 μg/kg/min and dobutamine at 7.5 μg/kg/min. Her revised vitals showed a blood pressure of 95/75 mm Hg, heart rate of 140 beats/min and a temperature of 37.0°C. Rapid physical examination revealed soft heart sounds with a gallop rhythm. There was no audible murmur. Air entry was reduced bilaterally but clear. There were no adventitious sounds appreciated. Her extremities were warm, there was no cyanosis.

The patient was taken for emergent right and left cardiac catheterisation with Swan Ganz studies. Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) was inserted for optimal haemodynamic support. Swan Ganz catheter showed a central venous pressure of 15 mm Hg, pulmonary artery pressure 30/21 mm Hg with a mean of 26 mm Hg, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure of 16 mm Hg, cardiac index of 2.03 L/min/m2, cardiac output of 3.72 L/min, systemic vascular resistance of 1247 dyn-s/cm5 and pulmonary vascular resistance of 215 dyn-s/cm5. Coronary angiogram was not done because the coronary arteries were known to be normal in her previous study 4 years prior. Because the patient was very sick, formal left ventriculogram was not considered. Hand injection of limited quantity of dye in the left ventricle showed severe global hypokinesis with apical hyperkinesis. Her initial arterial blood gas revealed a pH of 7.18, Paco2 of 37 mm Hg, Pao2 of 91 mm Hg, HCO3– of 14 mmol/L and a lactate of 2.5 mmol/L. Thyroid-stimulating hormone and cortisol were within normal range. Troponin T and creatine kinase were both elevated at 846 ng/L and 200 u/L, respectively.

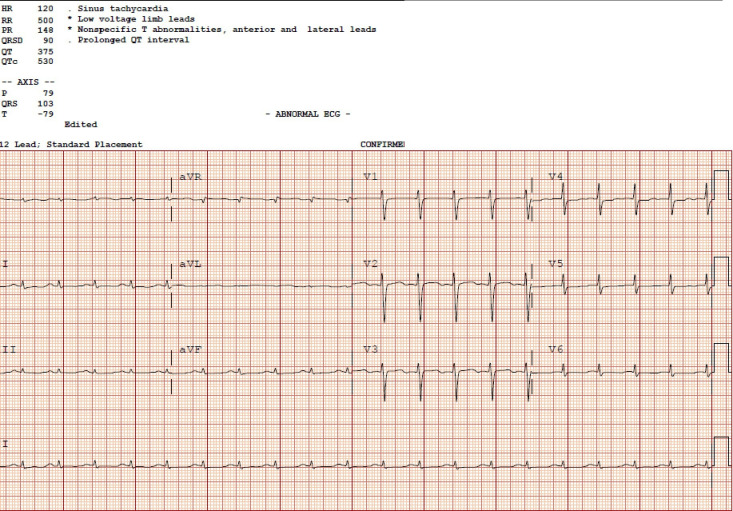

Other pertinent investigations included a C reactive protein of 33 mg/L, creatinine of 108 μmol/L, sodium of 127 mmol/L, glucose of 14.5 mmol/L, initial B-natriuretic peptide of 5021 ng/L, haemoglobin of 87 g/L and white cell count of 14.42×109/L. Liver enzymes were all normal. Chest X-ray revealed pulmonary oedema. ECG post resuscitation revealed sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 120, low voltages in the limb leads, non-specific ST segment changes in the anterior leads and a corrected QT (QTc) interval of 530 ms (figure 1). Initial presenting ECG had showed sinus bradycardia with severe hypotension as the patient was in a precode situation.

Figure 1.

ECG on admission to the coronary care unit. HR, Heart rate 120 beats per minute, RR, RR interval 500 ms, PR, PR interval 148 ms, QRSd, ventricular depolarization 90ms, QT, QT interval 375 ms, QTc, corrected QT interval 530 ms.

Her condition improved in the coronary care unit. She was weaned off inotropic support after 5 days. As her haemodynamics and overall condition improved, she was extubated.

When she was able to provide a history, she mentioned that she had been feeling unwell for about 1 week prior to admission with symptoms of an upper respiratory tract infection. She had omitted to take her maintenance dose of hydrocortisone (10 mg two times per day) as well as her levothyroxine (150 μg/day) during that period, even though she had been instructed to double her steroid dose during acute illness. She mentioned that she had been under duress, balancing her work as a substitute teacher as well as looking after herself and her family.

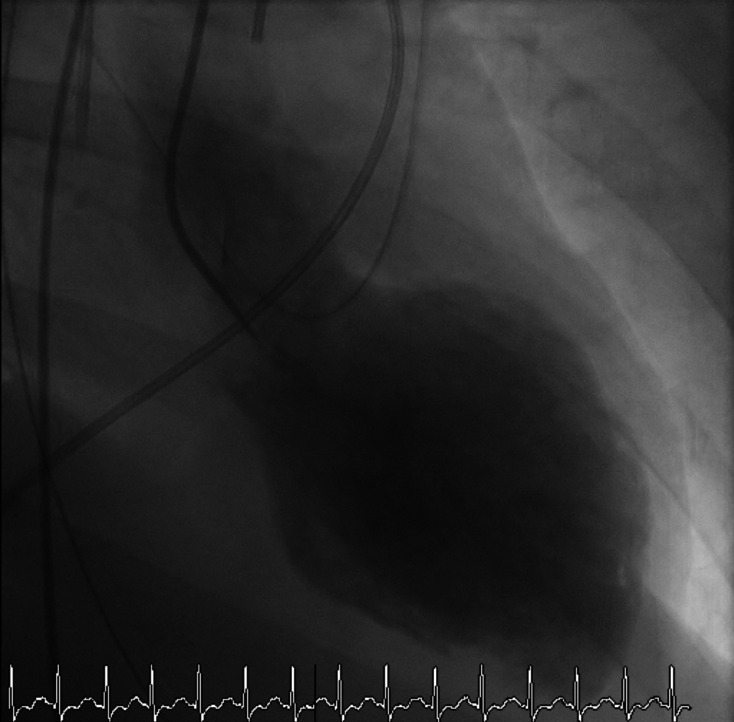

Interestingly, approximately 4 years prior, the patient had presented with a similar catastrophic scenario requiring inotropic and mechanical ventilatory support. Diagnostic work-up at that time had revealed APS II and classical TTS (figure 2). Her transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) had showed severe systolic dysfunction, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was about 10%–15%. Cardiac catheterisation had showed normal coronaries and LV angiogram showed the typical apical ballooning of TTS (videos 1 and 2). She had recovered fully from that episode with normalisation of systolic function and had an LVEF of 50%–55%. She was on heart failure enhancing medications for about 6 months after the initial presentation of TTS. However, she was lost to follow-up and had stopped all her cardiac medications.

Figure 2.

Initial left ventricular angiogram 4 years prior to this presentation, demonstrating typical Takotsubo syndrome.

Video 1.

Video 2.

Investigations

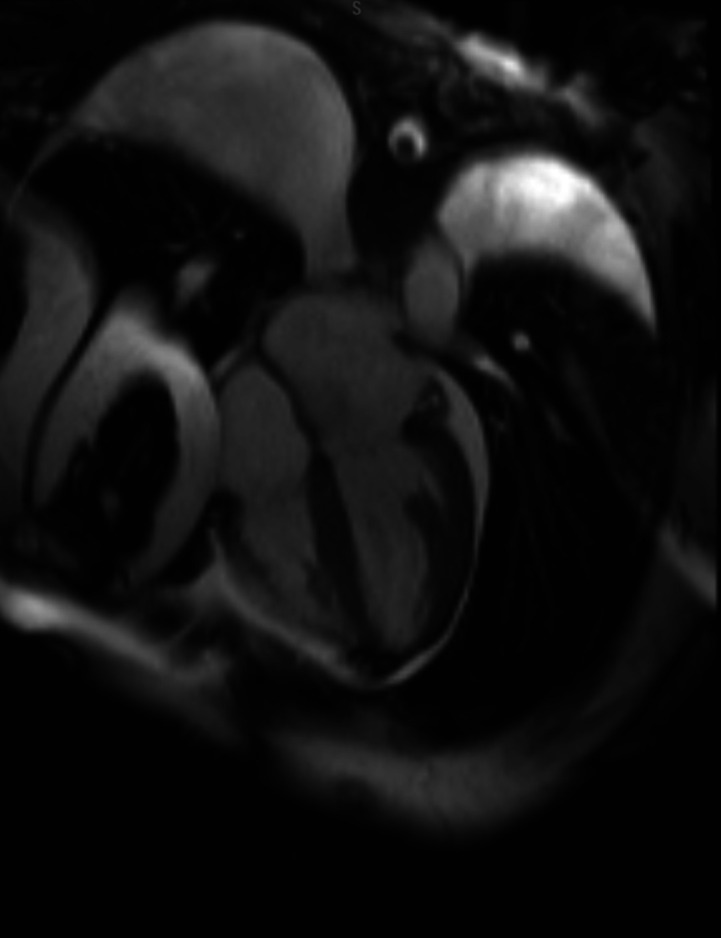

CT head did not reveal any significant intracranial abnormalities. Initial TTE showed severe hypokinesis of the basal left ventricular wall segments with a hyperdynamic apical region. These findings were in keeping with reverse TTS, also known as apical variant TTS. The ejection fraction was approximately 15%. There was no evidence of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Repeat TTE was performed on day 6 and revealed an ejection fraction of about 40%–45%. There were patchy regional wall abnormalities with the mid-ventricular walls appearing akinetic while the apical segments were relatively spared (video 3). There was no left ventricular thrombus. Cardiac MRI revealed a mildly dilated left ventricle with global hypokinesis and moderate systolic dysfunction (figure 3). There was no evidence of late gadolinium enhancement, excluding myocardial scarring and fibrosis. A small pericardial effusion measuring 8 mm was noted as well as a large right and moderate-sized left pleural effusion. There were no findings suggestive of myocarditis or myocardial infarction.

Video 3.

Figure 3.

Cardiac MRI demonstrating a mildly dilated left ventricle with global hypokinesis and moderate systolic dysfunction.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses included shock secondary to Addisonian crisis, septic shock secondary to a respiratory tract infection and/or meningitis and fulminant myocarditis causing cardiogenic shock. There were no cases of diagnosed COVID-19 in our province at the time, so myocarditis secondary to COVID-19 was not considered. The patient was initially treated empirically with antibiotics/antivirals for meningitis with ceftriaxone, vancomycin and acyclovir due to her altered sensorium. However, lumbar puncture findings were inconclusive and the antibiotics were discontinued.

Left heart catheterisation documented a left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP) of 29 mm Hg. This markedly elevated LVEDP with a reduced cardiac index of 2.03 L/min/m2 was in keeping with cardiogenic shock. The LVEDP dropped rapidly to 18 mm Hg post-IABP insertion.

Treatment

She was started on high dose intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg two times per day to tide her over the Addisonian crisis. Inotropy and an IABP were provided for haemodynamic support. An endotracheal tube was inserted to maintain her airway. She was also cautiously diuresed with furosemide.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient responded very well to therapy and was stabilised. At discharge, her medications included ramipril 2.5 mg/day, bisoprolol 2.5 mg/day, spironolactone 12.5 mg/day, levothyroxine 150 μg/day, hydrocortisone 20 mg in the morning and hydrocortisone 10 mg at noon. She was also instructed to double her steroid doses if she were to become acutely unwell.

On outpatient follow-up at 3 months, the patient had fully recovered from her critical illness and was doing very well. She has joined an exercise programme to improve her aerobic capacity. Echocardiogram showed a completely recovered left ventricular systolic function. The ejection fraction was 65%–70%. There was no evidence of diastolic dysfunction or valvular dysfunction. Regional wall motion had completely normalised and there was no evidence of scarring.

Discussion

This case highlights a unique presentation of typical and reverse TTS secondary to recurrent Addisonian crises. Our patient had initially presented with an Addisonian crisis compounded by hypothyroidism and was diagnosed with APS II, which is also known by its eponym, Schmidt’s syndrome. Both crises were complicated by cardiogenic shock and TTS and posed few therapeutic challenges. TTS is triggered by a wide spectrum of physical, mental and emotional stressors though there are reported cases of unidentifiable stressors.3 The pathophysiology is still unclear but the most widely accepted mechanism is the catecholamine surge that leads to myocardial stunning.4 Other proposed mechanisms of TTS include coronary artery vasospasm, coronary microvascular dysfunction and dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction as well as increased left ventricular end-diastolic pressures.4 The term ‘neuro-myocardial failure’ has been used to encompass the relationship between the stressor and the acutely stressed heart.

The iInternational Takotsubo diagnostic criteria, most widely accepted, provides a diagnostic platform to assess the likelihood of TTS. It is a scoring system comprising seven parameters namely female sex (25 points), emotional trigger (24 points), physical trigger (13 points), absence of ST-segment depression (except in lead aVR) (12 points), psychiatric disorders (11 points), neurological disorders (9 points) and QT prolongation (6 points). These are ranked based on their diagnostic import, with a maximum score of 100 points.5 The simplicity of these criteria makes it easily obtaineable in the emergency room and excludes the need for a diagnostic imaging modality. Patients with a score value greater than 70 points have a diagnostic probability of almost 100%. Our patient had a score of at least 80 based on the criteria.

Initial haemodynamic stabilisation of our patient called for effective doses of inotropes. This ‘inotropic reflex’ may have exacerbated her heart failure and caused her clinical deterioration. There are reported cases of acute stress cardiomyopathy induced by intravenous epinephrine and dobutamine during cardiac procedures. Large doses of inotropes may also worsen dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, by increasing basal hypercontractility, more so in the apical variant.6 Lyon et al suggest that the use of inotropes should be generally contraindicated in TTS as they may exacerbate or prolong the acute phase in severe cases of cardiogenic shock with progressive end organ dysfunction by supra-activation of catecholamine receptors or their downstream molecular pathways.7

Santoro et al demonstrated in a small case series that the use of a non-catecholamine inotrope such as levosimendan may be safe to use in patients with TTS.8 This promising alternative to inotropes in this particular scenario needs rigorous clinical evaluation before it can attain therapeutic standard as a catecholamine-sparing inotrope. Our patient required an IABP for optimal haemodynamic support, reduction of left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and to limit the use of inotropy. She stabilised rapidly thereafter with decreased inotropic requirements. Case reports recommend the use of IABP in patients with TTS complicated by refractory cardiogenic shock. However, recent data from the IABP-SHOCK 11 trial have been neutral.7 The consensus viewpoint is to avoid the use of IABP in these patients. Their use may also worsen dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, especially in the apical variant. It is recommended that extracorporeal membrane oxygenator or left ventricular assist device be used in these critical situations as a bridge-to-recovery as there is an excellent chance that ventricular function will recover fully.

There are very few reported cases of adrenal insufficiency associated with TTS.9 It is proposed that in the adrenal crisis, hyponatraemia and hypoglycaemic play a role in precipitating TTS. Hypoglycaemia stimulates the sympathetic nervous system and similarly, hyponatraemia can lead to changes in the calcium/sodium channels which can lead to myocardial injury. However, in this patient, glucose and sodium levels were within normal range on her initial blood work. Due to her critical illness, the patient was under a significant amount of physical and biochemical stress and this may have provoked the sympathetic nervous system to over activate.

The typical TTS appearance is a transient apical dyskinesis and basal hyperkinesis; however, our patient showed basal akinesis with apical hypercontractility, also known as reverse TTS.10 There are several phenotypes of TTS such as apical, basal, midventricular and focal.10 11 Compared with typical TTS, reverse TTS occurs in 1%–23% of all TTS cases and is predominantly reported in younger individuals.10 Data from the International Takotsubo Registry also suggest that atypical TTS usually present with a higher initial ejection fraction compared with the apical variant.12

The pattern of regional wall motion abnormality in TTS points towards a neurally mediated mechanism of cardiac injury.13 14 It has been suggested that certain variants of TTS may be attributed to the involvement of different branches of the cardiac sympathetic nervous system.14 In the classical variant, anatomic and physiological factors are believed to make the cardiac apex more vulnerable to the characteristic ballooning that is the hallmark of this cardiomyopathy. Anatomically, it is relatively avascular as it is located in a watershed area of the major branches of the coronary arteries, predisposing it to ischaemic insults. It also lacks a three-layered myocardium which impairs its ability to regain elasticity after maximal wall stretch. Increased sympathetic terminals have also been described in the apex as compared with the base, which makes the apex more susceptible to sudden catecholamine storm. Paradoxically, the apex is known to be hypercontractile in variant forms of TTS!9 Though various theories have been postulated to explain this paradox, including migratory form of TTS as part of its phenotypic spectrum, undiagnosed plaque rupture, sudden excessive left ventricular afterload and increased left ventricular end-systolic pressure, none have been accepted as the defining biochemico-haemodynamic catalyst for this acute, reversible and migratory cardiomyopathy.

Genetic profiling and expression in the acute phase of TTS are currently underway and polymorphisms in adrenergic receptors and FMR 1 gene mutations have been reported.15 16

The German Italian Spanish Takotsubo (GEIST) Registry provides further insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms that may predispose the heart to recurrent attacks of this acute cardiomyopathy. In fact, the incidence of recurrent TTS is estimated at 4% in this multicentre TTS registry. However, recurrent TTS with a variant pattern is quite common with up to 20% of the recurrences.17 It also highlighted the fact that there were no significant differences between the groups with and without recurrences, except for arterial hypertension. Interestingly, 46% of patients had a new stressor as the triggering event for the recurrence. Three (10%) patients in the series presented with apical TTS as the index event with subsequent midventricular variant TTS at the recurrence event. Their proposed hypothesis is that a previous episode of TTS may somehow protect the involved region, with a higher vulnerability of other parts. However, this is not consistent with other reports of recurrent cases of TTS with the same acute remodelling pattern as the index event.18 The registry also documents that the highest number of recurrences was observed earlier (up to 5 years) after the index event, suggesting that the myocardium remains vulnerable at this first stage after the index event. Recurrence could also be explained by the fact that beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors are prescribed for the short-term until the LVEF has normalised. A normal LVEF however does not imply normal left ventricular systolic function. More than 50% patients in the registry were admitted with a beta-blocker, ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II antagonist and paradoxically the latter two group of drugs were more effective at reducing recurrent TTS than the former, thus challenging the hyperadrenergic stimulation theory of cardiac injury.19–21 Singh et al report that therapy with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers may prevent recurrences, while Brunetti et al recommend combined therapy with beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors/ARBs for effective prevention of recurrent TTS.21 22

This raises the more important question of what is the optimal management strategy of this cardiomyopathy with respect to drug combination and duration. It is clear that a normal LVEF can no longer be used as a surrogate for normal left ventricular systolic function. There are reports of small apical infarcts, bystander subendocardial infarcts, involving a small proportion of the acutely dysfunctional myocardium in TTS.7 However, these infarcts are insufficient to explain the acute regional wall motion abnormality observed in these patients but may represent ‘nidus’ for recurrence in the same territory in these patients.

The concurrence of TTS and APS II is very rare with few cases reported in the literature. These have reported an association of cardiac dysfunction with APS in patients with autoimmune cardiomyopathy, non-reversible dilated cardiomyopathy, peripartum cardiomyopathy and TTS.23 24 The pathogenetic mechanism of cardiac dysfunction in APS remains an enigma. Proposed theories include hormonal storm, catecholamine surge secondary to hypotension and hypoglycaemic and transient dysfunction of the sodium/calcium ion pump in the setting of hyponatraemia associated with APS, resulting in impaired cardiac contractility.

Sudden acute cardiac remodelling, in typical and atypical forms, as a response to a wide spectrum of stressors support the favoured theory of catecholamine storm acting via the neuro-cardiac axis, resulting in ‘neuro-myocardial’ failure.25 Other players will surface as diagnostic criteria for TTS continue to evolve. Normalisation of LVEF by short-term beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers undermines disease residua that may predispose affected patients to recurrence. Recurrent TTS is no respecter of territories!

Learning points.

In patients presenting with Addisonian crises complicated by refractory shock, it is important to consider concurrent Takotsubo syndrome (TTS).

High dose steroids and haemodynamic support form the cornerstone of therapy.

Combined therapy with beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers should be considered for longer duration in patients who present with recurrent TTS as normalisation of left ventricular ejection fraction does not imply normalisation of left ventricular systolic function.

Four different phenotypes of TTS have been described: apical variant, midventricular variant, basal variant and rare focal variant.

Patients with TTS are at risk of TTS recurrence. TTS is not associated with a favourable prognosis, mortality rates are comparable to that of acute coronary syndrome.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the contribution of Siddarth Nosib in the submission of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: On behalf of my coauthor and myself, I have the honour to submit the above case report for potential publication in your esteemed journal. MT was responsible for the main write up of the case as she was closely involved in the care of the patient. SN reviewed the manuscript and made appropriate corrections. I was the attending physician responsible for the care of the patient during her admission and follow-up.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program Autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 2, 2020. Available: https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/diseases/7611/autoimmune-polyglandular-syndrome-type-2 [Accessed 17 Mar 2020].

- 2. Elesber AA, Prasad A, Lennon RJ, et al. Four-Year recurrence rate and prognosis of the apical ballooning syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:448–52. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gianni M, Dentali F, Grandi AM, et al. Apical ballooning syndrome or takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a systematic review. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1523–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nef HM, Möllmann H, Akashi YJ, et al. Mechanisms of stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Nat Rev Cardiol 2010;7:187–93. 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ghadri J-R, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (Part II): diagnostic workup, outcome, and management. Eur Heart J 2018;39:2047–62. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abraham J, Mudd JO, Kapur N, et al. Stress cardiomyopathy after intravenous administration of catecholamines and beta-receptor agonists. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1320–5. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, et al. Current state of knowledge on takotsubo syndrome: a position statement from the Taskforce on takotsubo syndrome of the heart failure association of the European Society of cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:8–27. 10.1002/ejhf.424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santoro F, Ieva R, Ferraretti A, et al. Safety and feasibility of levosimendan administration in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a case series. Cardiovasc Ther 2013;31:e133–7. 10.1111/1755-5922.12047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gupta S, Goyal P, Idrees S, et al. Association of endocrine conditions with takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive review. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7 10.1161/JAHA.118.009003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Awad HH, McNeal AR, Goyal H. Reverse takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a comprehensive review. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:460. 10.21037/atm.2018.11.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ramaraj R, Movahed MR. Reverse or inverted takotsubo cardiomyopathy (reverse left ventricular apical ballooning syndrome) presents at a younger age compared with the mid or apical variant and is always associated with triggering stress. Congestive Heart Failure 2010;16:284–6. 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2010.00188.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ghadri JR, Cammann VL, Napp LC, et al. Differences in the clinical profile and outcomes of typical and atypical takotsubo syndrome. JAMA Cardiology 2016;1:335 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.0225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pierpont GL, DeMaster EG, Cohn JN. Regional differences in adrenergic function within the left ventricle. Am J Physiol 1984;246:H824–9. 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.6.H824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kawano H, Okada R, Yano K. Histological study on the distribution of autonomic nerves in the human heart. Heart Vessels 2003;18:32–9. 10.1007/s003800300005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kleinfeldt T, Schneider H, Akin I, et al. Detection of FMR1-gene in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a new piece in the puzzle. Int J Cardiol 2009;137:e81–3. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharkey SW, Maron BJ, Nelson P, et al. Adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in patients with stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol 2009;53:53–7. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. El-Battrawy I, Santoro F, Stiermaier T, et al. Incidence and clinical impact of recurrent takotsubo syndrome: results from the GEIST registry. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:1. 10.1161/JAHA.118.010753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eitel I, von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F, Bernhardt P, et al. Clinical characteristics and cardiovascular magnetic resonance findings in stress (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. JAMA 2011;306:277–86. 10.1001/jama.2011.992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santoro F, Ieva R, Musaico F, et al. Lack of efficacy of drug therapy in preventing takotsubo cardiomyopathy recurrence: a meta-analysis. Clin Cardiol 2014;37:434–9. 10.1002/clc.22280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sharkey SW, Windenburg DC, Lesser JR, et al. Natural history and expansive clinical profile of stress (tako-tsubo) cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:333–41. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brunetti ND, Santoro F, De Gennaro L, et al. Drug treatment rates with beta-blockers and ACE-inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and recurrences in takotsubo cardiomyopathy: a meta-regression analysis. Int J Cardiol 2016;214:340–2. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh K, Carson K, Usmani Z, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of incidence and correlates of recurrence of takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2014;174:696–701. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Karavelioglu Y, Baran A, Karapinar H, et al. Reversible cardiomyopathy associated with autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome type II. Intern Med 2013;52:981–5. 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.7188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yehya A, Sperling L, Jacobs S, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a patient with presumptive autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome II. Cardiac Cath Lab Dir 2011;1:118–20. 10.1177/2150133511419200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015;373:929–38. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]