PURPOSE:

Studies suggest that patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) have superior survival when treated at specialized cancer centers (SCCs). However, the association of early mortality (< 60 days) with location of initial care, sociodemographic factors, and complications has not been evaluated in pediatric and young adult (YA) patients with ALL.

METHODS:

Using the California Cancer Registry linked to hospitalization data, we identified pediatric and YA patients with ALL who received inpatient leukemia treatment between 1991 and 2014. Patients were classified as receiving all or part/none of their care at an SCC (Children’s Oncology Group– or National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center). Propensity scores were created for treatment at an SCC in each age group. Multivariable, inverse probability–weighted Cox proportional hazards regression models identified factors associated with early mortality. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs.

RESULTS:

Among 6,531 newly diagnosed pediatric (≤ 18 years) and YA (19 to 39 years of age) patients with ALL, 1.6% of children and 5.4% of YAs died within 60 days of diagnosis. Most children received all of their care at an SCC (n = 4,752; 85.7%) compared with 35.5% of YAs (n = 1,779). Early mortality rates were lower in pediatric patients and those receiving all care at an SCC (pediatric: all, 1.5%, v part/none, 2.4%; P = .049; YAs: all, 3.2%, v part/none, 6.6%; P = .001). However, in adjusted models, receiving all care at an SCC was associated with significantly lower early mortality in YAs (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.32 to 0.81), but not in pediatric patients (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.47 to 1.25).

CONCLUSION:

YAs with ALL experience significant reductions in early mortality after treatment at SCCs.

INTRODUCTION

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common pediatric cancer,1,2 and despite significant improvements in survival, outcomes continue to vary by race/ethnicity,3,4 neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES), and age.5 Differences in time to diagnosis, access to medical care, treatment regimens,6,7 treatment adherence, and biologic features have been implicated in these survival disparities.4,8 Importantly, in a population-based (n = 1,380) study in Los Angeles county, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with ALL treated at Children’s Oncology Group (COG) or National Cancer Institute (NCI)–designated cancer centers were found to have better survival than those treated at community hospitals,9 suggesting that specialized care may mitigate sociodemographic disparities in survival outcomes in patients with ALL.7

Early cancer mortality has been found to vary by age, race/ethnicity, county-level income, and year of diagnosis in children,10,11 but these associations have not been fully investigated in AYAs with cancer. In addition, higher early mortality in children has been associated with pulmonary complications,12 infections,10 bleeding,10 and organ failure10 that occur more frequently during induction and consolidation therapy.10,12,13 However, no large population-based studies have examined the impact of sociodemographic factors, complications, and location of care on early mortality in pediatric and young adult (YA) patients with ALL. Therefore, using population-based cancer registry data linked to hospitalization data in California, we examined the impact of location of treatment and complications on early mortality in pediatric (0 to 18 years old) and YA (19 to 39 years old) patients with ALL to fill this gap and inform decisions regarding the optimal treatment setting for these patients.

METHODS

Study Population

Pediatric and YA patients (0 to 39 years old) who were hospitalized in California from 1991 to 2014 with a first primary diagnosis of ALL were eligible for this analysis. A diagnosis of ALL was defined using morphology codes from the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3): B cell, T cell, or not otherwise specified. After excluding patients without a record linkage number (RLN) to hospital data (n = 4,015), with unspecified race/ethnicity (n = 76), and with a subsequent cancer within 60 days of diagnosis (n = 15), 6,531 patients were included in the final study population. In this database, serial records for a single patient are linked using an anonymized form of the Social Security number, called the RLN. This allows for the possible evaluation of multiple admissions from one patient over time.

Data Sources

The California Cancer Registry (CCR) was linked with the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development Patient Discharge Database (PDD). The CCR contains information on nearly all patients diagnosed with cancer in California.14 From the CCR, we obtained information on diagnosis date, age at diagnosis, sex, marital status, neighborhood SES, health insurance, and type of initial treatment (eg, chemotherapy). The PDD contains detailed information on all hospitalizations from all acute care hospitals in California, except federal hospitals (n = 14). The PDD includes information on principal diagnosis and up to 24 secondary diagnoses on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision, clinical modification; ICD-9), hospital admission date, hospital name, and location.

Specialized cancer centers (SCCs) were defined as COG- and NCI-designated centers.8 COG hospitals are considered centers of excellence for treatment of pediatric cancer.15 However, a similar designation does not exist for YAs; therefore, we used NCI comprehensive cancer center designation as a surrogate.9 There are 28 SCCs in California (four COG/NCI-, 20 COG-, and four NCI-designated cancer centers without COG designation). Treatment at SCCs was defined as care received at a COG- or NCI-designated center for pediatric patients 18 years of age or younger at diagnosis and at an NCI-designated center for those YAs older than 18 years of age at diagnosis. On the basis of prior research, we presumed that pediatric patients treated at COG centers were placed on or treated per COG protocols.7,16 Patients were classified as receiving all or part/none of their care at an SCC within the first 60 days of diagnosis. They were still considered to have received all care at an SCC if their only admission at a non-SCC was their first diagnostic admission. No pediatric patients and only five YA patients received chemotherapy during their diagnostic admission at a non-SCC. To determine the accurate location of inpatient treatment, case listings of patients’ admissions were reviewed by two oncologists.

For health insurance, we combined publicly insured (Medicaid/Medi-Cal and other government-assisted programs) and uninsured together in the analysis, given the historically small proportion of uninsured pediatric and AYA patients with cancer observed in previous studies that may reflect retroactive enrollment in Medicaid at diagnosis.17 SES was determined using a previously developed neighborhood SES measure in the CCR.18 The presence of comorbidities in the 2 years before diagnosis or at diagnosis were determined using the Elixhauser index on the basis of ICD-9 codes linked to the admission.19,20 Comorbidities were categorized as any versus none. Complications were grouped into the following categories: bleeding, sepsis, thrombosis, liver failure, renal failure, respiratory failure, and cardiac arrest.21 Presence of a complication was determined by the corresponding ICD-9 code linked with the patient’s admission within the first 60 days from diagnosis.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics characterized the study population. We used χ2 tests to examine the relationship between early mortality and location of care. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for ordinal variables. Propensity score methodology was used in each age group to balance patients by location of care. Multivariable logistic regression was used to estimate the associations between baseline sociodemographic and clinical factors with location of care, which was then used to build a propensity score. Results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs. The standardized mean differences in baseline characteristics between patients receiving all versus part/none of their care at an SCC was used to determine the effectiveness of the propensity score adjustment. The nearly equal propensity score distributions in each group indicated that covariables used to estimate the propensity scores had a similar distribution. Early mortality was defined as death within 60 days of ALL diagnosis. Inverse probability–weighted, Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were then performed to estimate the association of complications and location of care with early mortality, adjusting for baseline sociodemographic and clinical factors. Pediatric and YA patients were analyzed separately. A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate early mortality in pediatric and YA patients with ALL in the CCR, regardless of RLN. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs. Interactions of location of care and complications with early mortality by age group were also examined. In addition, multivariable logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with having any complication. Analyses that included health insurance were limited to patients diagnosed from 1996 forward. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and a two-sided P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics and Location of Inpatient Care

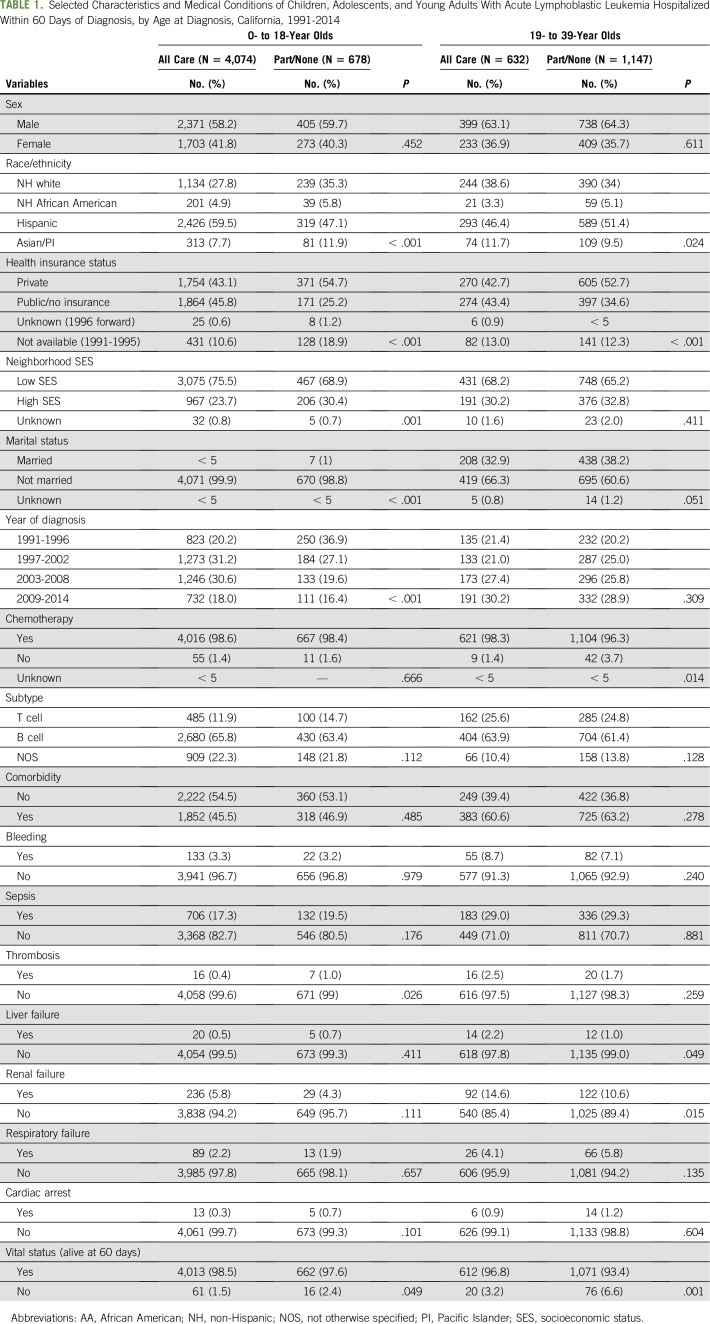

The study population included 6,531 patients with newly diagnosed ALL (Table 1). Although the majority of pediatric patients received all their inpatient care at an SCC (85.7%), only a minority of YA patients received all care at an SCC (35.5%). A higher percentage of both pediatric (45.8% v 25.2%) and YA (43.4% v 34.6) patients with public/no insurance received all care (v part/none) from an SCC.

TABLE 1.

Selected Characteristics and Medical Conditions of Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Hospitalized Within 60 Days of Diagnosis, by Age at Diagnosis, California, 1991-2014

The overall 60-day mortality rate was 1.6% in pediatric and 5.4% in YA patients and differed by location of treatment of each age group (ages 0 to 18 years: all SCC, 1.5%, v part/none SCC, 2.4%; P = .049; ages 19 to 39: all SCC, 3.2%, v part/none SCC, 6.6%; P = .001). Rates of complications were similar by location of care in pediatric and YA patients, except for thrombosis in pediatric patients (all, 0.40%, v part/none, 1.00%; P = .03) and renal failure in YAs (all, 14.6%, v part/none, 10.6%; P = .015).

Factors Associated With Location of Care

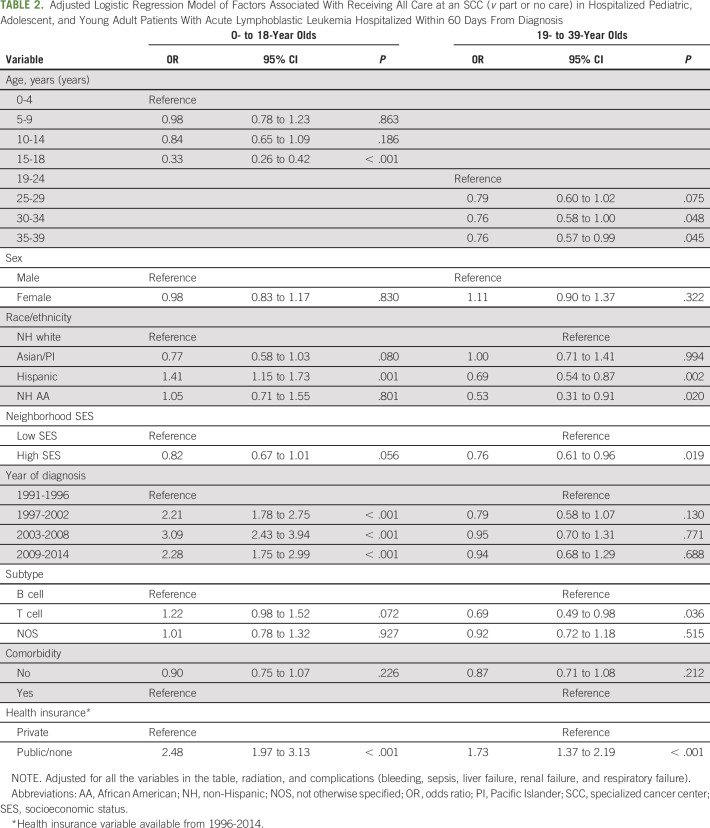

Multivariable adjusted logistic regression analyses showed that, among pediatric patients, factors associated with receiving all care at an SCC were younger age; were Hispanic (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.73, v non-Hispanic white) race/ethnicity; had a more recent year of diagnosis (1997 to 2002: OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.78 to 2.75; 2003 to 2008: OR, 3.09; 95% CI, 2.43 to 3.94; 2009 to 2014: OR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.75 to 2.99); and had public/no insurance (OR, 2.48; 95% CI, 1.97 to 3.13, v private; Table 2). Receiving all care at an SCC among YAs was associated with public/no insurance (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.37 to 2.19). YAs of Hispanic (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54 to 0.87) or African American (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.91) race/ethnicity, who were older (30 to 34 years: OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.58 to 1.00; 35 to 39 years: OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.99, v 19 to 24 years) or who resided in high SES neighborhoods (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.96, v low SES) were less likely to receive all care at an SCC.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted Logistic Regression Model of Factors Associated With Receiving All Care at an SCC (v part or no care) in Hospitalized Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Hospitalized Within 60 Days From Diagnosis

Factors Associated With Early Mortality

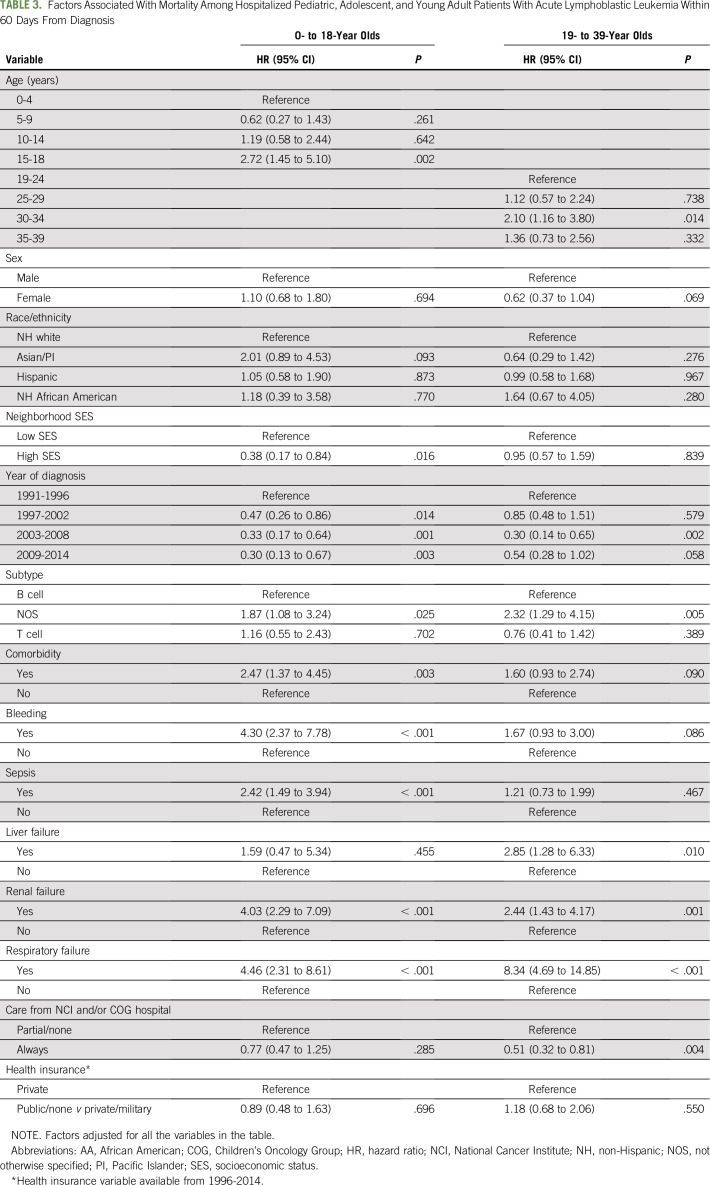

In inverse probability–weighted, multivariable models, higher early mortality in pediatric patients was associated with older age (15 to 18 years: HR, 2.72; 95% CI, 1.45 to 5.10; v 0 to 4 years), complications of bleeding (HR, 4.30; 95% CI, 2.37 to 7.78), sepsis (HR, 2.42; 95% CI, 1.49 to 3.94), renal failure (HR, 4.03; 95% CI, 2.29 to 7.09), respiratory failure (HR, 4.46; 95% CI, 2.31 to 8.61), and comorbidities (HR, 2.47; 95% CI, 1.37 to 4.45, v no comorbidity; Table 3). In pediatric patients, there was no association of early mortality with location of care in multivariable models. In the sensitivity analysis including pediatric patients without an RLN in the CCR, we found similar early mortality associations with race/ethnicity, neighborhood SES, and health insurance, except among Hispanic children (OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.24 to 3.58), who had a higher early mortality than we observed in our study population (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Factors Associated With Mortality Among Hospitalized Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Within 60 Days From Diagnosis

In YAs, early mortality was associated with older age (30 to 34 years: HR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.16 to 3.80), liver failure (HR, 2.85; 95% CI, 1.28 to 6.33), renal failure (HR, 2.44; 95% CI, 1.43 to 4.17), and respiratory failure (HR, 8.34; 95% CI, 4.69 to 14.85; Table 3). In YAs, receiving all care at an SCC was associated with lower early mortality (HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.32 to 0.81, v part/none). In the sensitivity analysis including all YAs without an RLN in the CCR, we found similar associations with early mortality and sociodemographic factors. There was no significant interaction between location of care, complications, and early mortality in pediatric or YA patients.

Factors Associated With Complications

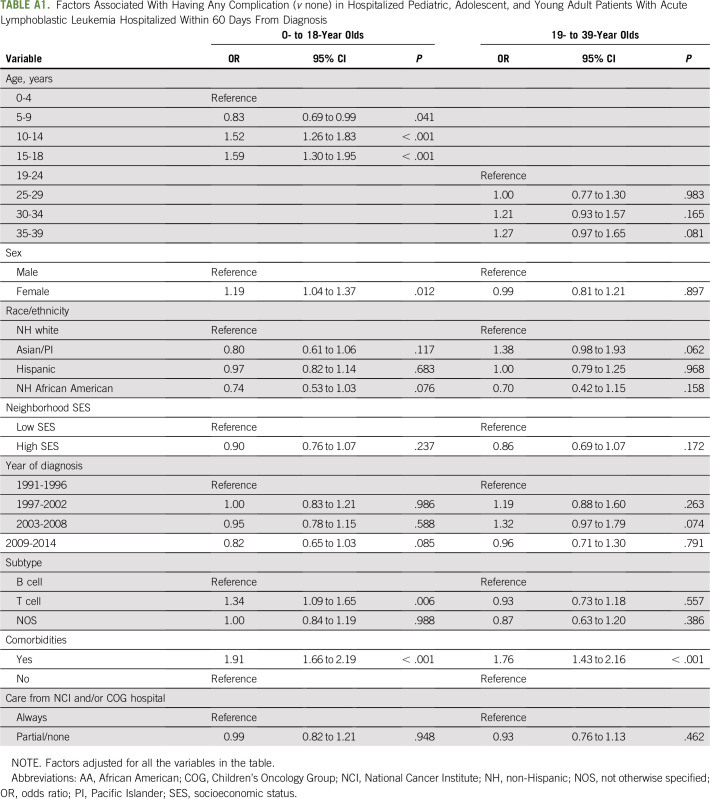

For multivariable logistic regression analyses, older age (10 to 14 years: OR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.26 to 1.83; 15 to 18 years: OR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.30 to 1.95), female sex (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.37, v male sex), T-cell leukemia (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.65, v B-cell leukemia), and prior comorbidity (OR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.66 to 2.19) were associated with treatment complications in pediatric patients (Appendix Table A1, online only). In YAs, only prior comorbidity (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.43 to 2.16) was associated with treatment complications. Location of care was not associated with treatment complications in either age group.

DISCUSSION

In our large California population-based cohort of pediatric and YA patients with ALL, YAs who received all of their initial care at an SCC had lower early mortality than YAs who received only part or none of their care at these facilities. This relationship persisted in inverse probability–weighted, multivariable analyses adjusted for sociodemographic factors, comorbidities, and complications. Complications, including renal failure and respiratory failure, affected early mortality in both age groups. Rates of complications were similar by location of care, except for somewhat lower rates of thrombosis in pediatric patients and higher rates of renal failure in YAs receiving all their care at an SCC.

Although, to our knowledge, our study is the first to consider the relationship between early mortality and location of care among pediatric and YA patients with ALL, our findings of lower early mortality among patients with ALL receiving all care at SCCs are consistent with other cancer studies suggesting that treatment at an SCC is associated with improved survival outcomes.9,22,23 The lower early mortality seen at SCCs in this study is most likely due to factors related to the expertise of delivering complex care at these facilities, because these findings persisted after controlling for age, sex, race/ethnicity, SES, insurance, diagnosis year, ALL subtype, comorbidities, and complications. Superior ALL outcomes after treatment at SCCs also may relate to differences in treatment regimens or increased access to clinical trials and other specialized services at these institutions.7,16,24-26 Because we could not consider specific treatment factors underlying the lower early mortality at SCCs, we acknowledge that these factors may also be present at non-SCCs with expertise in treating YA patients with ALL. The lack of association of decreased mortality with treatment at an SCC in pediatric patients is most likely related to statistical power, because the vast majority (85.7%) were managed at an SCC.

In this study, specific complications were evaluated and were significantly associated with early mortality in both pediatric and YA patients. Infectious,10,13,27 bleeding/thrombosis,27 and pulmonary complications12 have been shown in other studies to be associated with mortality in patients with ALL. However, unlike this study, these previous studies did not evaluate the factors associated with complications, including age and location of care. Although rates of complications were similar by location of care, except for thrombosis and renal failure, our findings suggest that pediatric and YA patients with a prior comorbidity were more likely to have a treatment-related complication, and practitioners should have a heightened awareness of this when monitoring these patients.

Our study did not find associations between race/ethnicity, neighborhood SES, and health insurance with early mortality. Although no studies have evaluated the association between sociodemographic factors and early mortality in YA patients, a recent population-based cancer registry study found sociodemographic factors to be associated with 30-day mortality in children (0 to 19 years of age) with hematologic malignancies.11 In that study, children of African American or Hispanic race/ethnicity and who resided in lower SES counties were found to have higher 30-day mortality.11 Our findings may have differed because our study was limited to patients with ALL who linked to our hospitalization database from the CCR. However, in the sensitivity analyses evaluating early mortality in all pediatric and YA patients with ALL in the CCR, we did not find any sociodemographic differences, with the exception that Hispanic children also had higher early mortality, suggesting that we may not be capturing all high-risk Hispanic patients in our analysis. Given the significant differences we observed in early mortality by location of care, it is critical to evaluate the disparities and barriers in access to SCCs in YAs with ALL.

In our study, relative to non-Hispanic white patients, Hispanic YAs and African American YAs were less likely to receive all their care at an SCC. Differences in access to SCCs have been described previously for patients with cancer in the pediatric28,29 and AYA age groups,8 with studies finding that Hispanic patients in both age groups had decreased utilization of SCCs. In the study of AYA patients with ALL in Los Angeles county, a similar association of decreased utilization of SCCs was found for Hispanic and African American patients ages 22 to 39 years, but there was no association observed in those patients younger than 22 years of age.9 For patients older than 21 years of age in California, California Children’s Services provides comprehensive public insurance coverage and requires that patients with cancer be seen at COG centers. Therefore, these patients with public insurance may have increased access to SCCs.30 However, our findings suggest that Hispanic and African American YAs, independent of insurance type and neighborhood SES, experience barriers to accessing care at an SCC. Furthermore, we observed that YAs with higher SES were less likely to receive all their care at an SCC, suggesting that factors other than access to care influence where patients receive their care and should be the focus of future research.

We also found increased mortality with advancing age. Although, to our knowledge, no prior studies have assessed early mortality in YAs with ALL, recent estimates of 30-day mortality for pediatric patients with ALL (1.3%; excluding infant ALL) were found to be higher than previously reported rates (0.7%).11 Although our study focused on 60-day mortality, when we looked at 30-day mortality from 1992 to 2011 (the study years for Green et. al11), children had a similar rate of 1.1% and AYAs had a rate of 3.7%. The differences in age persisted even when accounting for comorbidities, which are more prevalent among older patients and are associated with higher early mortality. Although our findings suggest that the adverse effect of age on early mortality can be mitigated by receiving treatment at an SCC, the differences in outcomes may also be due to differences in biology, treatment regimens,7,16 and social factors that we were unable to consider in this study.25

A limitation of this study is that we were unable to link 33% of patients who were identified in the CCR to the hospitalization database, many of whom were pediatric patients (87%). However, our analyses of sociodemographic factors and early mortality were similar in sensitivity analyses, including pediatric and YA patients without an RLN from the CCR, except with regard to Hispanic children, as discussed previously. Although this may relate to the linkage being based on Social Security number, the proportion of Hispanic patients was similar among patients with ALL with and without an RLN. In addition, our data lack specific treatment details for each patient. However, although chemotherapy regimens can vary between SCCs and non-SCCs,7 a prior study found that treatment at an SCC was associated with increased likelihood of receiving a pediatric regimen, which may contribute to improved survival at these centers.7 Finally, we did not have details on important biologically derived prognostic and predictive factors to consider in our propensity scores and early mortality analyses. As a result, there is likely residual confounding from the imbalance in baseline characteristics among patients treated at SCCs versus non-SCCs. However, we used propensity score–weighted models to mitigate this bias; therefore, it is less likely that the differences in measured baseline characteristics could account for the difference noted in outcomes. Despite these limitations, this linked database allows for robust population-level analysis of sociodemographic and clinical factors affecting early mortality that has not been previously described.

In conclusion, treatment at an SCC seems to be associated with significantly lower early mortality in YAs with ALL. After adjusting for sociodemographic and clinical factors, including complications, the reduction in mortality associated with SCCs may be due to improved access to clinical trials and other specialized services available at these institutions. These results add to the growing literature demonstrating superior YA leukemia outcomes after treatment at SCCs. On the basis of the results of our study we advocate that YAs with ALL be treated at SCCs. This may not be feasible for all patients; therefore, additional research is warranted to determine the differences in care and treatment at SCCs that account for observed disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the Children’s Miracle Network (S-CMNTK16). The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 5NU58DP006344; the National Cancer Institute’s SEER Program under contract HHSN261201800032I awarded to the University of California, San Francisco, contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201800009I awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the State of California, Department of Public Health, National Cancer Institute, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their contractors and subcontractors. Poster presented at the American Society of Hematology Meeting, Atlanta, GA, December 9-12, 2017.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Factors Associated With Having Any Complication (v none) in Hospitalized Pediatric, Adolescent, and Young Adult Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Hospitalized Within 60 Days From Diagnosis

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Elysia M. Alvarez, Marcio Malogolowkin, Ann Brunson, Brad H. Pollock, Ted Wun, Theresa H.M. Keegan

Financial support: Theresa H.M. Keegan

Administrative support: Ann Brunson

Provision of study materials or patients: Ted Wun

Collection and assembly of data: Qian Li, Ann Brunson, Brad H. Pollock

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Decreased Early Mortality in Young Adult Patients With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treated at Specialized Cancer Centers in California

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Brad H. Pollock

Consulting or Advisory Role: Astellas Pharma

Lori Muffly

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Corvus Pharmaceuticals

Consulting or Advisory Role: Pfizer, Kite Pharma

Research Funding: Shire, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Astellas Pharma

Ted Wun

Honoraria: Pfizer, Janssen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen, Pfizer

Research Funding: Janssen (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Daiichi Sankyo (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Janssen

Theresa H.M. Keegan

Research Funding: Shire (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xie Y, Davies SM, Xiang Y, et al. : Trends in leukemia incidence and survival in the United States (1973-1998). Cancer 97:2229-22352003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al. : Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: Challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol 28:2625-26342010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goggins WB, Lo FFK: Racial and ethnic disparities in survival of US children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Evidence from the SEER database 1988-2008. Cancer Causes Control 23:737-7432012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim JY, Bhatia S, Robison LL, et al. : Genomics of racial and ethnic disparities in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer 120:955-9622014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keegan TH, Ries LA, Barr RD, et al. : Comparison of cancer survival trends in the United States of adolescents and young adults with those in children and older adults. Cancer 122:1009-10162016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boissel N, Auclerc MF, Lhéritier V, et al. : Should adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia be treated as old children or young adults? Comparison of the French FRALLE-93 and LALA-94 trials. J Clin Oncol 21:774-7802003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muffly L, Alvarez E, Lichtensztajn D, et al. : Patterns of care and outcomes in adolescent and young adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A population-based study. Blood Adv 2:895-9032018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez E, Keegan T, Johnston EE, et al. : Adolescent and young adult oncology patients: Disparities in access to specialized cancer centers. Cancer 123:2516-25232017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfson J, Sun CL, Wyatt L, et al. : Adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia: Impact of care at specialized cancer centers on survival outcome. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26:312-3202017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng S, Pole JD, Sung L: Early deaths in pediatric acute leukemia: A population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma 55:1518-15222014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green AL, Furutani E, Ribeiro KB, et al. : Death within 1 month of diagnosis in childhood cancer: An analysis of risk factors and scope of the problem. J Clin Oncol 35:1320-13272017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erdur B, Yilmaz S, Oren H, et al. : Evaluating pulmonary complications in childhood acute leukemias. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30:522-5262008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rubnitz JE, Lensing S, Zhou Y, et al. : Death during induction therapy and first remission of acute leukemia in childhood: The St. Jude experience. Cancer 101:1677-16842004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiatt RA, Tai CG, Blayney DW, et al. : Leveraging state cancer registries to measure and improve the quality of cancer care: A potential strategy for California and beyond. J Natl Cancer Inst 107:djv107.2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Children’s Oncology Group : 2018. https://childrensoncologygroup.org/

- 16.Muffly L, Lichtensztajn D, Shiraz P, et al. : Adoption of pediatric-inspired acute lymphoblastic leukemia regimens by adult oncologists treating adolescents and young adults: A population-based study. Cancer 123:122-1302017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg AR, Kroon L, Chen L, et al. : Insurance status and risk of cancer mortality among adolescents and young adults. Cancer 121:1279-12862015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R, et al. : Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control 12:703-7112001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. : Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care 36:8-271998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. : Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 43:1130-11392005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrara F, Schiffer CA: Acute myeloid leukaemia in adults. Lancet 381:484-4952013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutierrez JC, Cheung MC, Zhuge Y, et al. : Does Children’s Oncology Group hospital membership improve survival for patients with neuroblastoma or Wilms tumor? Pediatr Blood Cancer 55:621-6282010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meadows AT, Kramer S, Hopson R, et al. : Survival in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia: Effect of protocol and place of treatment. Cancer Invest 1:49-551983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke ME, Albritton K, Marina N: Challenges in the recruitment of adolescents and young adults to cancer clinical trials. Cancer 110:2385-23932007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith AW, Seibel NL, Lewis DR, et al. : Next steps for adolescent and young adult oncology workshop: An update on progress and recommendations for the future. Cancer 122:988-9992016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zebrack B, Mathews-Bradshaw B, Siegel S: Quality cancer care for adolescents and young adults: A position statement. J Clin Oncol 28:4862-48672010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lund B, Åsberg A, Heyman M, et al. : Risk factors for treatment related mortality in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56:551-5592011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamberlain LJ, Pineda N, Winestone L, et al. : Increased utilization of pediatric specialty care: A population study of pediatric oncology inpatients in California. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 36:99-1072014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukherjee D, Kosztowski T, Zaidi HA, et al. : Disparities in access to pediatric neurooncological surgery in the United States. Pediatrics 124:e688-e6962009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chamberlain LJ, Chan J, Mahlow P, et al. : Variation in specialty care hospitalization for children with chronic conditions in California. Pediatrics 125:1190-11992010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]