PURPOSE:

Performance status (PS), an established prognostic surrogate of cancer survival, is a physician-synthesized metric of patient symptoms and mobility that is prone to bias and subjectivity. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–Cancer (PROMIS-Ca) Bank, a patient-centric patient-reported outcome (PRO) evaluation of physical function (PF), fatigue, depression, anxiety, and pain, shares subject matter with PS and, therefore, may also be prognostic while eliminating physician interpretation.

METHODS:

Patients at Huntsman Cancer Institute were assessed using the NCI PROMIS-Ca Bank. Using tablets at routine office visits, PF, fatigue, depression, anxiety, and pain scores were collected from patients with advanced melanoma, non–small-cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, and breast cancer. A PRO score collected at a single time point within 6 months of metastatic diagnosis for each patient was merged with curated clinical outcome data. The association of PROs, overall survival (OS), and hospitalization-free survival (HFS) were assessed in multivariable analysis that included sex and cancer type.

RESULTS:

Two hundred eighty-two complete sets of patient data were available for analysis. All 5 PRO domains were strongly prognostic of OS and HFS. While the PRO domains were interrelated with moderate to strong correlations (0.40-0.79), multivariable regression suggested that PF was most strongly associated with the clinical outcomes of OS (P < .001) and HFS (P < .001).

CONCLUSION:

NCI PROMIS-Ca PROs may be prognostic of both cancer survival and likelihood of hospitalization. Future prospective studies are needed for all major prognostic factors to fully understand the independent prognostic value of PROs.

INTRODUCTION

Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance statuses (PSs)1,2 are subjective, physician-synthesized compilations of patients’ symptoms, physical and self-care ability, and symptom burden. PS is believed to reflect physiologic reserve and tumor burden and is used to make decisions about cancer treatment, eligibility in clinical trials, and estimations of prognosis. PS is subject to bias by physicians, patients, and caregivers and may not be truly reflective of how well a patient is doing at any given time point. Previous studies have demonstrated significant interobserver variability in the measurement of PS, with health professionals, including oncologists and nurses, assigning greater PS scores than patients with cancer at the same time points.3,4 Patients with advanced cancer typically experience a period of preserved PS during the initial management of their disease followed by decompensation, increased symptom burden, and frequent hospitalization. Data from a Medicare analysis in 2012 demonstrated that 65% of patients with advanced cancer were hospitalized within 30 days of their death, and 25% of these patients required intensive care unit level of care.5 In addition, analyses have shown that up to 50% of patients with advanced cancer receive cancer-directed therapy within 30 days of their death6 and that it is often of limited survival benefit and at a substantial cost.7 This creates a significant financial burden for our health care system. More importantly, it negatively affects patients’ quality of life because those who receive chemotherapy at the end of life are less likely to receive the benefits and appropriate duration of hospice care.8

Patient self-reported health measures are potentially more accurate reflections of an individual’s physical functioning and emotional well-being because these are not subject to physician interpretation and bias.4 In other studies, the use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in the clinic has demonstrated improved physician-patient communication, symptom awareness and management, and patient quality of life.9-11 Furthermore, implementation of PROs into academic oncology practice has been shown to reduce the number of emergency department visits and hospitalizations, prolong patient tolerability of chemotherapy, and improve overall survival (OS).12-14

In 2004, the National Institutes of Health developed the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) to validate PROs for use in both clinical oncology practice and clinical research. Our study examines the relationship between OS and hospitalization-free survival (HFS) and 5 PROMIS domain measures among patients with metastatic cancer in an academic oncology setting.15

METHODS

As a demonstration project and quality initiative, PROs were administered through iPads (Apple, Cupertino, CA) to patients randomly and at no > 3-month intervals starting in May 2016 to June 2017. The PROMIS PRO measures included were physical function, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression15 (Data Supplement, online only). Patients who completed PRO measures within 6 months of a metastatic cancer diagnosis were included. At least 1 PRO was measured in 288 patients in this study, and all 5 PROs of interest were measured in 282 of the patients. Of note, 39 patients (13.5%) died and 79 (27.4%) had a hospitalization or died during the follow-up period. PRO scores from the time point of metastatic disease were merged with clinical outcome data using the Flatiron Health database, a nationwide longitudinal electronic health record–derived database that contains de-identified structured (laboratory results, prescription drugs) and unstructured data (radiology and pathology reports, medical care notes, and biomarkers) curated through technology-enabled abstraction and supplemented with third-party death information.16 Each data point sourced from unstructured documents was abstracted manually from patient charts while following precise prespecified procedures that have been developed and tested for feasibility. The chart abstractors were trained experts who underwent both conceptual and standardized testing procedures using the abstraction technology interface.17 Institutional review board approval of the study protocol was obtained before study conduct, and included a waiver of informed consent. Data provided to third parties were de-identified, and provisions were in place to prevent re-identification to protect patient confidentiality.

PROs were summarized by sex and disease site with a focus on the PRO subscales of interest, including physical function, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression. For each PRO, the hazard ratio (HR) is the factor of increase or decrease in the force of mortality, defined as hospitalization or mortality for HFS per 1 unit of PRO. Relationships between PRO domains were summarized graphically using Pearson’s correlation coefficients along with 95% CIs.

HFS and OS were assessed from the time of metastatic diagnosis to hospitalization or death, respectively, subject to right censoring. OS and HFS were summarized through Kaplan-Meier survival curves by disease site, sex, and tertiles of PROs both individually and cumulatively, along with corresponding log-rank tests. Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models were constructed for OS and HFS to evaluate the association of individual PRO domains, disease site, and sex. The analyses used to examine the association between PROs and OS and HFS make use of all the data for patients with the relevant PROs. Multivariable models were constructed through stepwise variable selection with P < .05 for the entry threshold and P ≥ .05 for the exit threshold.

RESULTS

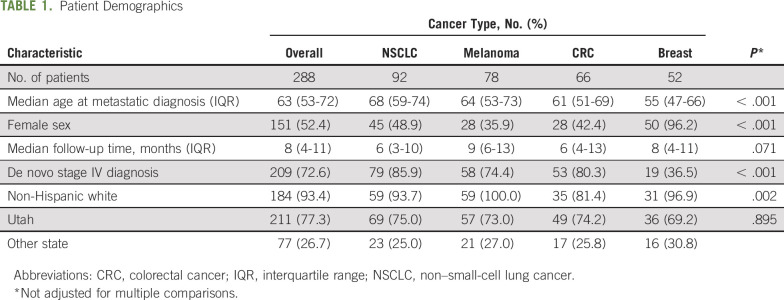

Data for patients with a single complete set of the 5 PRO domains (physical function, pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression) that occurred within 6 months of diagnosis of metastatic date or recurrence were available for 282 patients with cancers of the breast, lung, colon, and skin (melanoma). The median ages of those with cancers of the breast, lung, colon, and skin (melanoma) were 55, 68, 61, and 64 years at the time of metastatic diagnosis (Table 1). The median times of follow-up were 8 months, and 27% of patients died or had hospitalization events.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics

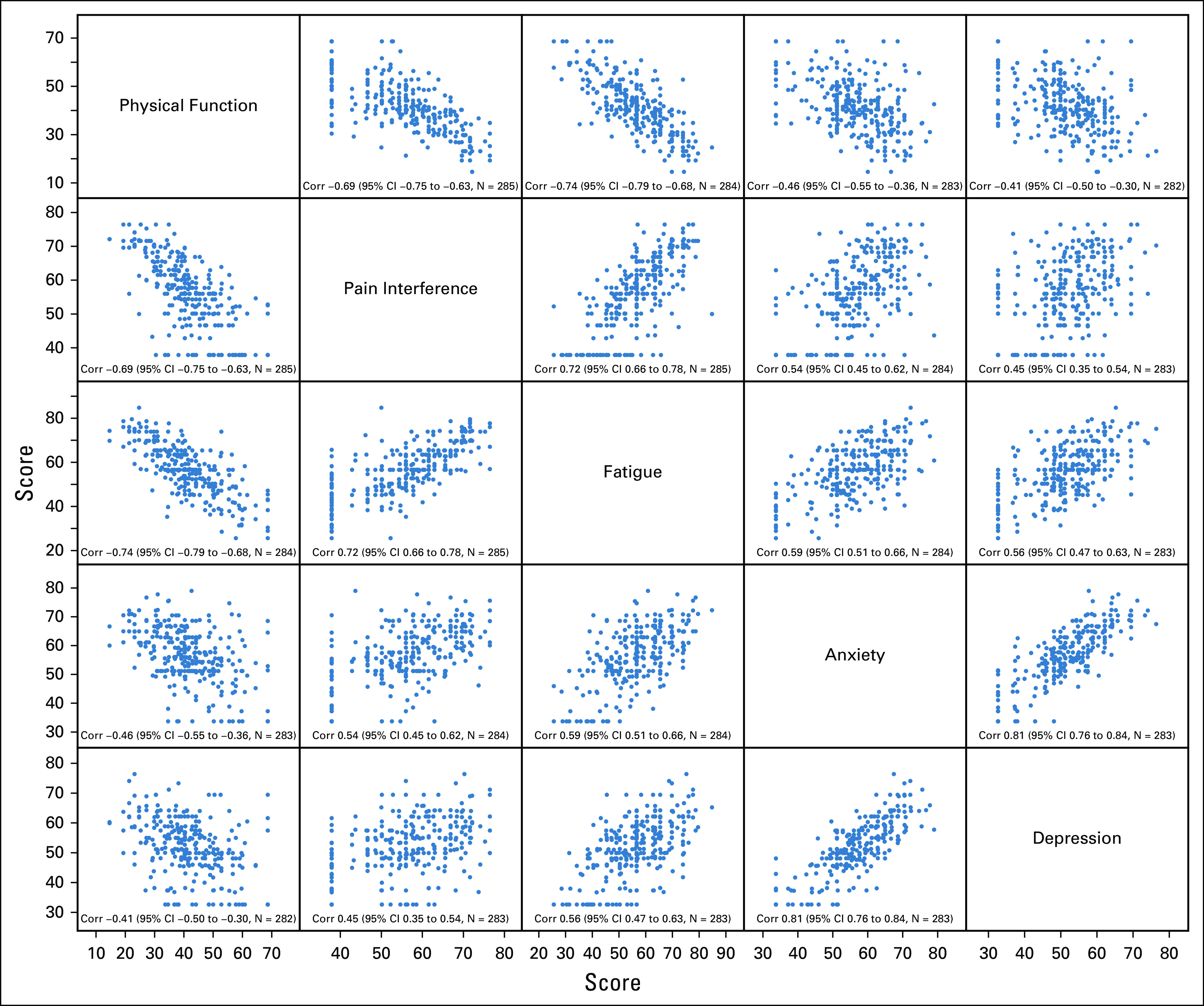

For most of the PRO domains, including pain interference, fatigue, anxiety, and depression, higher scores imply greater intensity of the symptom and greater patient distress, but for physical function, the opposite is true. Less physical function causes greater distress. The distributions of PROs across the 5 patient-reported domains of physical function, pain interference, fatigue, anxiety, and depression in our cohort of treated patients with advanced cancer at Huntsman Cancer Institute were relatively normally distributed. The 5 PRO domains were interrelated with moderate to strong correlations (0.40-0.79; Fig A1, online only).

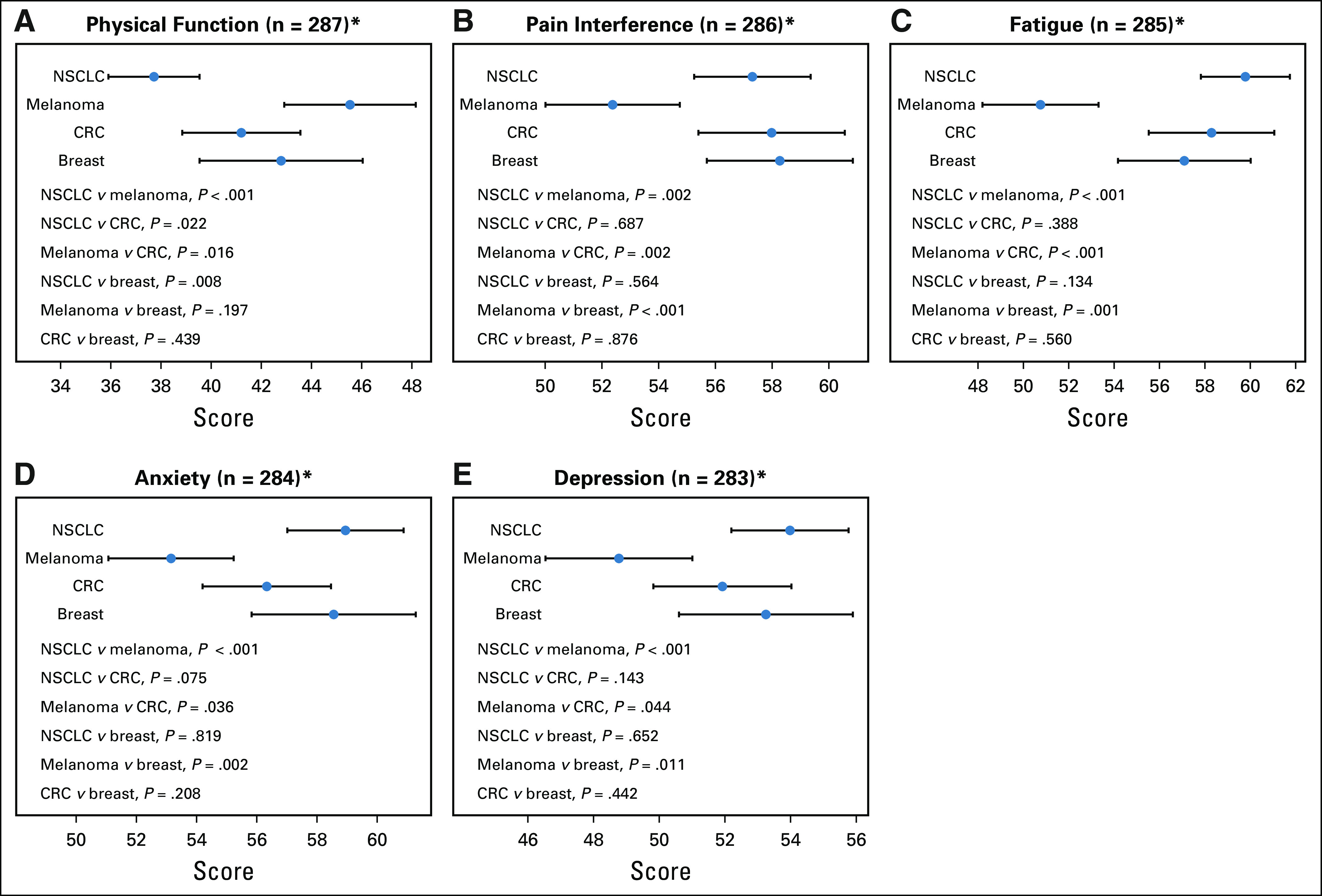

Cancer types were distinguished by different PRO patterns that reflected the different natural histories and treatment of these cancer types. Of note, patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) reported the greatest fatigue and the worst physical function compared with patients with advanced breast cancer (unadjusted P = .008), melanoma (unadjusted P < .001), and colorectal cancer (CRC; unadjusted P = .022; Fig 1). In contrast, patients with advanced melanoma reported the highest PRO scores for physical function, the lowest PRO scores for pain (unadjusted P = .002 compared with CRC, unadjusted P < .001 compared with breast, unadjusted P = .002 for NSCLC), the lowest PRO scores for fatigue (unadjusted P < .001 compared with NSCLC, unadjusted P < .001 compared with CRC, unadjusted P = .001 compared with breast), and the lowest PRO scores for anxiety and depression compared with the other disease groups (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Patient-reported outcome scores differ by cancer type in the 5 domains. (A) Physical function. (B) Pain interference. (C) Fatigue. (D) Anxiety. (E) Depression. CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non–small-cell lung cancer.

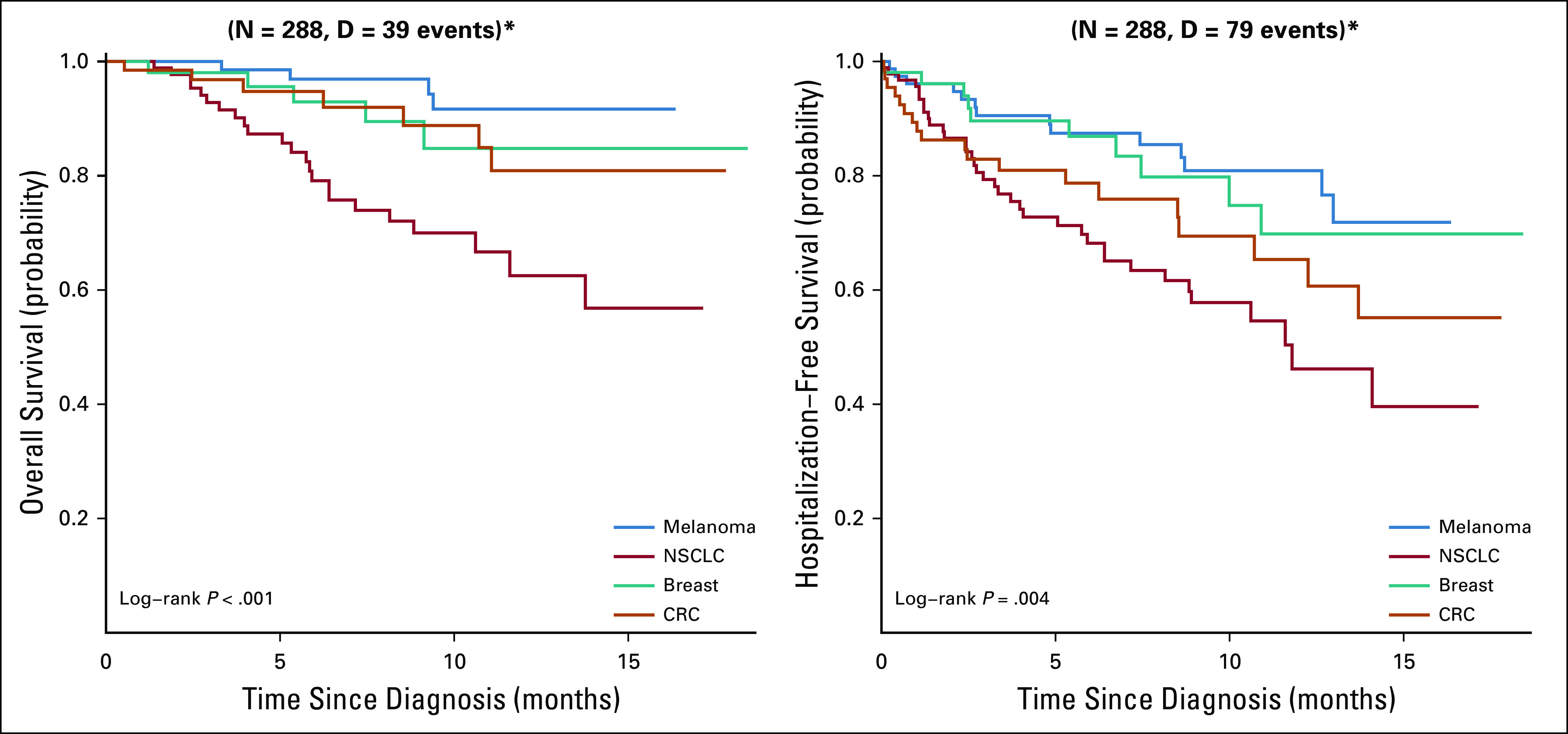

OS and HFS generally followed similar trends by disease type (Fig A2, online only). Patients with NSCLC demonstrated the worst 1-year HFS at 46.2% (95% CI, 33.3% to 64.0%) and 1-year OS at 62.5% (95% CI, 49.8% to 78.4%), whereas patients with melanoma demonstrated the best HFS and OS. Patients with breast and CRC showed similar 1-year OS at 84.8% (95% CI, 72.7% to 98.9%) and 80.9% (95% CI, 68.3% to 95.8%), respectively, and 1-year HFS at 69.8% (95% CI, 54.5% to 89.4%) and 65.3% (95% CI, 52.0% to 82.1%), respectively.

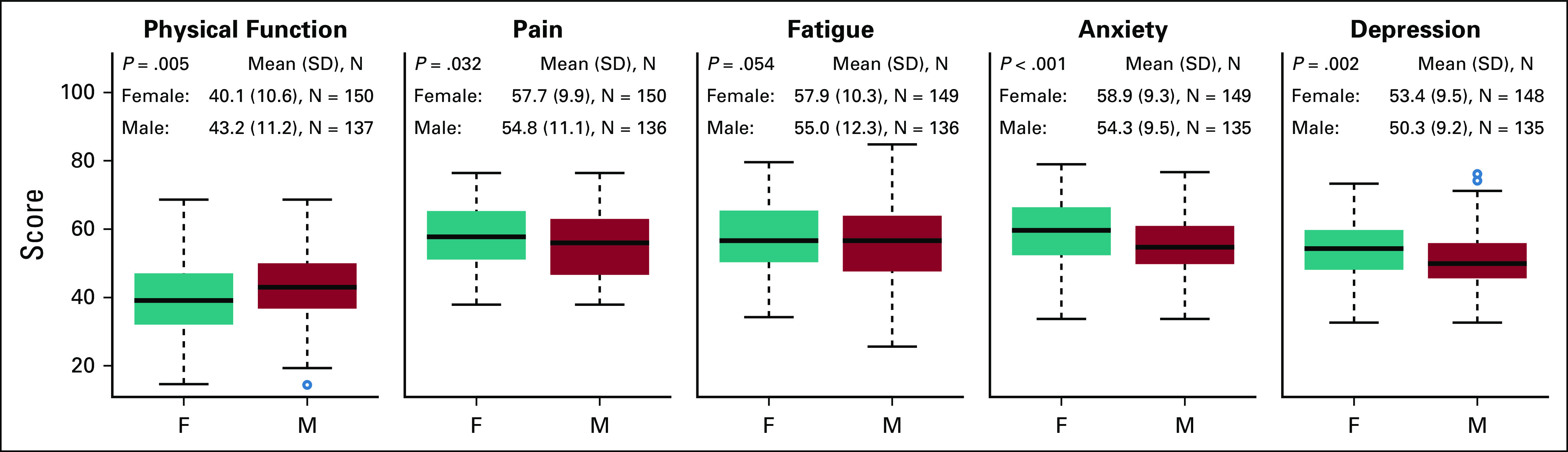

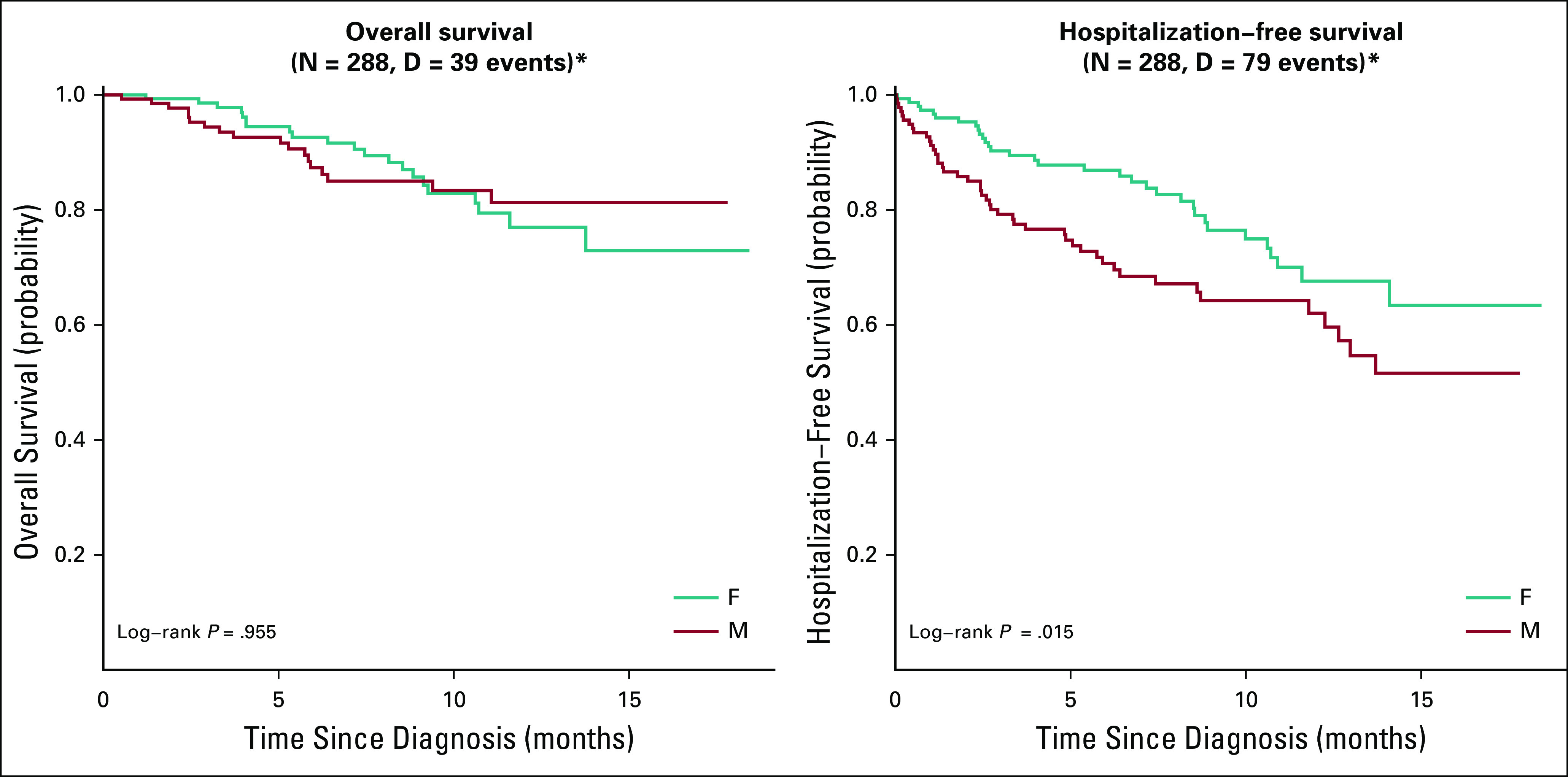

Compared with male patients, female patients had worse PRO scores, with lower levels of physical function and higher levels of pain, fatigue, anxiety, and depression across disease groups (Fig A3, online only). Of note, this did not predict for significantly worse HFS and OS outcomes among women (Fig A4, online only).

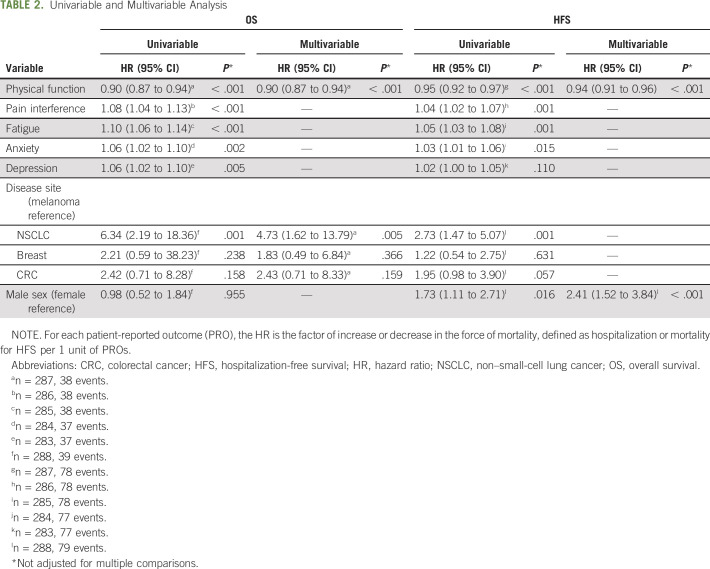

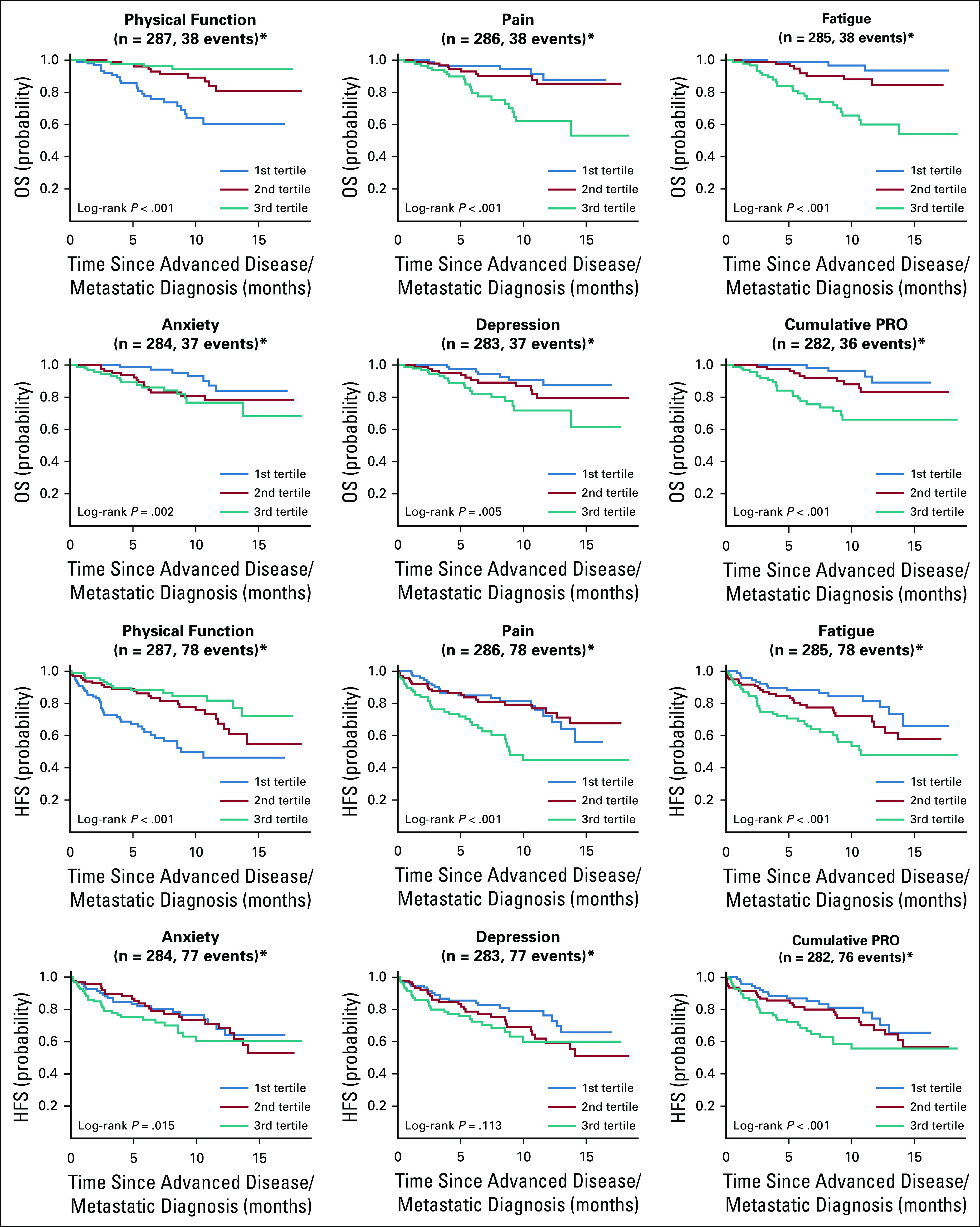

Across nearly all domains, a worse PRO score was associated with significantly shorter HFS and OS probability across all disease categories and sexes in univariable analysis (Table 2). An empiric grouping of PRO scores by tertiles graphically highlights these findings (Fig 2). Multivariable models were constructed through stepwise variable selection with a P value entry/exit threshold of .05. Physical function and disease site were predictive of OS, and after accounting for their impacts, neither sex nor other PRO domains had a statistically significant independent association with OS (Table 2). Physical function and sex were predictive of HFS, and after accounting for their impacts, neither disease site nor other PRO domains had a statistically significant independent association with HFS (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Analysis

Fig 2.

Association of patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores in 5 domains and cumulatively with overall survival (OS) and hospitalization-free survival (HFS).

DISCUSSION

Our data suggest that physical function and cancer site are predictive of OS, while physical function and sex are predictive of HFS in patients with metastatic melanoma, breast cancer, CRC, and NSCLC. These findings suggest a simple means of assessing an individual’s immediate risk of cancer morbidity and mortality (might be feasible), which could be used to trigger interventions on the behalf of the patient to result in improved quality of life for the patient and cost savings for the health care system.

Hospitalization in the setting of metastatic cancer is a common occurrence that is both costly and upsetting to patients and families.18 Frequently, these hospitalizations involve high-intensity care with often futile life-prolonging procedures and intensive care unit stays.3 Retrospective claims data from 2002 to 2009 showed that mean total cancer-related costs in the last 6 months before death were $74,212.19 Of note, 55% of the costs comprised inpatient hospitalization, which rose steeply in the last month before death.19

Given the cost, impact on quality of life, and often futile interventions, HFS is an important outcome measure. Not unsurprisingly, it correlates strongly with OS. Because the event of hospitalization occurs earlier than death, it potentially offers clinicians the opportunity to intervene earlier when the patient is not preterminal. These interventions may preserve functional status, prevent repeat hospitalizations, or minimize the length of stay. Knowledge of the prognosis for hospitalization and survival of a patient with cancer provides other opportunities for risk-based intervention to improve patient care, such as earlier institution of palliative care or hospice or, at least, greater in-depth discussion of both. PS predicts those who are more likely to benefit from treatment and have fewer adverse effects,20 so a PRO refinement of this measure would be beneficial.

We found sex-based differences in PRO score reporting in this study. Worse PRO scores reported by women may be related to increased toxicities across drug classes, which are believed to be due to differences in drug metabolism, total dose received despite differences in body weight, and adherence to therapy.21 It is also possible that similar outcomes in women despite worse reported PRO scores may be due to response bias or sex-based communication differences in adverse event reporting that resulted in earlier intervention for symptom management.

Overall, our results are in line with previous findings. The review of Gotay et al22 showed that PROs have the potential to predict survival, often better than PS. However, evidence for the prognostic value of specific PROs is limited and often related to a specific cancer (eg, lung, pancreatic, brain). For example, evidence exists for patient-reported functional scores,23 patient-reported symptom interference,24 patient-reported depression,25 or patient-reported fatigue.

A limitation of our study is that we relied on a PRO obtained at 1 time point within 6 months of a metastatic cancer diagnosis. Because of its retrospective nature, we cannot account for inherent selection bias and unknown potential confounders that may explain the differences in PRO scores between sex and disease groups. Finally, grouping beyond tertiles was not undertaken because of limited sample size and lack of prospective data. Information on clinical variables, including number and location of metastasis, tumor markers, insurance status, smoking status, and comorbid conditions, was not readily available for all patients and is another limitation of this retrospective study. Future prospective studies are needed with all major prognostic factors to fully understand the independent prognostic value of PROs. The use of real-world data is a strength of our study because these data support the notion that PRO assessment can and should become part of routine clinical care.

In summary, these data support the prognostic value of PROMIS PRO measures. In particular, the PROMIS PRO domain of physical function is prognostic (in the absence of other known prognostic factors) in this data set and merits prospective study in oncology practice. In addition, exploration of PRO trajectory over time may yield additional insights to guide patient supportive interventions. These efforts can move us closer to a goal of more patient-centric cancer care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Research reported in this publication used the Cancer Biostatistics Shared Resource at Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah.

APPENDIX

Fig A1.

Pairwise associations between PRO dimensions. *P values not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Fig A2.

Overall and hospitalization-free survival by disease site. *P values not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Fig A3.

Comparison of PRO dimensions between female and male patients. *P values not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Fig A4.

Overall and hospitalization-free survival by gender. *P values not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018 Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 1-5, 2018.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P30CA042014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Kathleen Kerrigan, Benjamin Haaland, Dominik Ose, Anna Weinberg Chalmers, Neal J. Meropol, Wallace Akerley

Financial support: Kathleen Kerrigan, Wallace Akerley

Administrative support: Kathleen Kerrigan, Wallace Akerley

Provision of study materials of patients: Kathleen Kerrigan, Neal J. Meropol

Collection and assembly of data: Kathleen Kerrigan, Benjamin Haaland, Dominik Ose, Tyler Haydell, Neal J. Meropol, Wallace Akerley

Data analysis and interpretation: Kathleen Kerrigan, Shiven B. Patel, Benjamin Haaland, Dominik Ose, Neal J. Meropol, Wallace Akerley

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Prognostic Significance of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Cancer

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Kathleen Kerrigan

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Bristol-Myers Squibb (I)

Speakers’ Bureau: OncLive

Shiven B. Patel

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Takeda Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

Benjamin Haaland

Consulting or Advisory Role: Prometics Life Sciences

Anna Weinberg Chalmers

Consulting or Advisory Role: Arthex (I), DePuy Synthes Companies (I)

Research Funding: Blueprint Medicines, TRACON Pharmaceuticals, Novartis

Tyler Haydell

Employment: Flatiron Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Flatiron Health, Roche

Neal J. Meropol

Employment: Flatiron Health

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Flatiron Health, Roche

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: US patent (20020031515): Methods of therapy for cancers characterized by overexpression of the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 protein

Wallace Akerley

Honoraria: AstraZeneca

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Incyte, Loxo Oncology

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Karnofsky DA, Abelmann WH, Craver LF, et al. : The use of the nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. With particular reference to bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer 1:634-6561948 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. : Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 5:649-6551982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sørensen JB, Klee M, Palshof T, et al. : Performance status assessment in cancer patients. An inter-observer variability study. Br J Cancer 67:773-7751993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ando M, Ando Y, Hasegawa Y, et al. : Prognostic value of performance status assessed by patients themselves, nurses, and oncologists in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 85:1634-16392001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morden NE, Chang CH, Jacobson JO, et al. : End-of-life care for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer is highly intensive overall and varies widely. Health Aff (Millwood) 31:786-7962012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braga S: Why do our patients get chemotherapy until the end of life? Ann Oncol 22:2345-23482011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, et al. : Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol 26:3860-38662008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saito AM, Landrum MB, Neville BA, et al. : The effect on survival of continuing chemotherapy to near death. BMC Palliat Care 10:14.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velikova G, Booth L, Smith AB, et al. : Measuring quality of life in routine oncology practice improves communication and patient well-being: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 22:714-7242004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. : What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 32:1480-15012014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Basch E, Barbera L, Kerrigan CL, et al: Implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine medical care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book 38:122-124, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. : Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 34:557-5652016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. : Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA 318:197-1982017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stukenborg GJ, Blackhall LJ, Harrison JH, et al. : Longitudinal patterns of cancer patient reported outcomes in end of life care predict survival. Support Care Cancer 24:2217-22242016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. : The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol 63:1179-11942010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12872. Curtis MD, Griffith SD, Tucker M, et al: Development and validation of a high-quality composite real-world mortality endpoint. Health Serv Res 53:4460-4476, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. doi: 10.1200/CCI.19.00013. Griffith SD, Miksad RA, Calkins G, et al: Characterizing the feasibility and performance of real-world tumor progression end points and their association with overall survival in a large advanced non–small-cell lung cancer data set. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 10.1200/CCI.19.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Whitney RL, Bell JF, Tancredi DJ, et al. : Hospitalization rates and predictors of rehospitalization among individuals with advanced cancer in the year after diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 35:3610-36172017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chastek B, Harley C, Kallich J, et al. : Health care costs for patients with cancer at the end of life. J Oncol Pract 8:75s-80s2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sweeney CJ, Zhu J, Sandler AB, et al. : Outcome of patients with a performance status of 2 in Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E1594: A phase II trial in patients with metastatic nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 92:2639-26472001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Unger JM, Vaidya R, Albain KS, et al: Sex differences in adverse event reporting in SWOG chemotherapy, biologic/immunotherapy, and targeted agent cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 37, 2019 (suppl; abstr 11588) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, et al. : The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol 26:1355-13632008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal JP, Chakraborty S, Laskar SG, et al. : Prognostic value of a patient-reported functional score versus physician-reported Karnofsky performance status score in brain metastases. Ecancermedicalscience 11:779.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barney BJ, Wang XS, Lu C, et al. : Prognostic value of patient-reported symptom interference in patients with late-stage lung cancer. Qual Life Res 22:2143-21502013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd-Williams M, Payne S, Reeve J, et al. : Thoughts of self-harm and depression as prognostic factors in palliative care patients. J Affect Disord 166:324-3292014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]