PURPOSE:

Adequate understanding of the goals and adverse effects of cancer treatment has important implications for patients’ decision making, expectations, and mood. This study sought to identify the degree to which patients and clinicians agreed upon the goals and adverse effects of treatment (ie, concordance).

METHODS:

Patients completed a demographic questionnaire, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer, the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Treatment Satisfaction-General questionnaire, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being questionnaire, and a 13-item questionnaire about the goals and adverse effects of treatment. Providers completed a 12-item questionnaire.

RESULTS:

One hundred patients (51 female) and 34 providers participated (questionnaire return rate mean difference, 5 days; SD, 16 days). Patient and provider dyads agreed 61% of the time regarding the intent of treatment. In cases of nonagreement, 36% of patients reported more optimistic therapy goals compared to providers. Patients and providers agreed 69% of the time regarding the patient’s acknowledgement and understanding of adverse effects. Patients who reported an understanding of likely adverse effects endorsed significantly lower distress scores (mean, 2.5) than those who endorsed not understanding associated adverse effects (mean, 4.1; P = .008).

CONCLUSION:

Timely data capturing of patient-provider dyadic ratings is feasible. A significant discrepancy exists between a substantial percentage of patients’ and providers’ views of the intent and adverse effects of treatment. Patients were almost always more optimistic about the intent of treatment. Higher rates of distress were noted in cases of discordance. Providers may benefit from conversational feedback from patients as well as other integrated feedback systems to inform them about patient understanding.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with cancer often have difficulty understanding the goals (ie, curative v noncurative) and adverse effects of their treatment.1 This may result in patient-provider discordance and can be a source of distress, especially when treatment expectations and informational preferences are not met. Treatment discordance may compromise patients’ ability to make treatment decisions that align with their preferences and values1,2 and may affect the degree to which patients agree to aggressive treatment regimens.3 Many patients with end-stage or complicated disease endorse the erroneous belief that their chemotherapy will be curative2,4 and may report expectations for survival that differ from their oncologists’.5 Among a sample of patients with metastatic breast cancer, more than 50% reported an expectation that treatment would extend life by 12 months or longer, whereas only approximately 10% of physicians endorsed this expectation.6 Gramling et al5 found that patient-provider opinions differed in terms of prognosis, and 89% of patients with advanced cancer were unaware that their optimistic outlooks were inconsistent with their physicians’ beliefs. Thus, communication about both the intent and adverse effects of treatment is a key component to helping patients to make informed health care decisions.

We define concordance as the level of patient-provider agreement about the intent and nature of treatment. High levels of concordance can lead to treatment satisfaction, adherence, and improved psychosocial adjustment for the patient.7 Concordance is influenced by patient, clinician, and relationship factors. Individual factors, including health literacy, distress, social support, treatment satisfaction, and spirituality, may influence the development of patient-provider concordance.3,6 Clinician factors, including years of experience and communication style, also may influence concordance levels. Finally, the dynamic information exchange between patient and provider is important to consider. First, patients and providers may have different perceptions about which goals are being prioritized when making treatment decisions. For instance, the emphasis on quality of life over aggressiveness of treatment may differ between provider and patient.8,9 Second, providers may make assumptions about patient values rather than directly asking about them,10 perhaps by drawing on their own values and preferences for treatment decision making. One study reported that oncologists desired less patient involvement in treatment plan decisions than patients expected and that these oncologists also incorrectly assumed that they were providing the level of explanation patients desired.11 Finally, providers may make incorrect assumptions about patients’ level of comprehension of the information provided,12 which leads them to truncate conversations prematurely.13 Patients may find it challenging to ask questions or disclose concerns.

The purpose of the current study is to identify the degree to which patients and clinicians agree upon the goals and adverse effects of treatment. Of note, we wanted to test the feasibility of recording data about the understanding of the patient’s treatment from both the patient and the provider at approximately the same time in their trajectory of active treatment. We hypothesized that patients and providers would exhibit a significant discrepancy in their perspective of the intent and adverse effects of treatment, patient-provider concordance would be associated with patient treatment satisfaction, and lower concordance would be associated with increased patient distress.

METHODS

Participants

Inclusion criteria for patients consisted of either having completed at least one cycle of treatment or undergoing treatment of at least 1 month or having a scheduled surgical treatment. Patients were 18 years of age or older and able to speak English.

Procedure

Participants were recruited, screened, and registered through chart reviews and phone calls. Interested patients who met the eligibility criteria arranged to meet individually with a research team member at the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center immediately before his or her next clinic appointment. At this time, research personnel obtained informed consent and asked each participant to complete all questionnaires before going to his or her appointment. The patient’s treatment provider was then approached to complete a provider packet. Research personnel collected both packets upon completion. We also recorded the number of years of experience in oncology care for all clinicians, including fellowship training. Stage of disease was recorded at the time the analytic case was opened. In the packet of questionnaires we examined patient and provider concordance rates on the intent and nature of treatment; patient and provider characteristics that correlate with discrepant patient perceptions about care; and the associations between concordance rates and distress, spirituality, social support, and treatment satisfaction.

Measures

Demographics.

Participants completed questions about their age, race, marital status, education level, and income. They also reported their primary diagnosis, date of diagnosis, and the date treatment began.

Concordance questionnaire (goals and understanding of treatment).

Patients and providers completed questionnaires (patient questionnaire, 13 items; provider questionnaire, 12 items; Appendix, online only) designed for this study to assess aspects of the treatment process, including understanding of the cancer diagnosis, understanding of the treatment plan and its likelihood of success, understanding and acknowledgment of adverse effects, and anticipated life expectancy. The concordance questionnaire was constructed by the experienced study team. Oncologists’ questionnaires closely mirrored patients’ and asked for a combination of their own medical opinions (eg, likelihood of treatment success) and their perceptions of what they believed their patients understood (eg, adverse effects).

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Treatment Satisfaction-General.

Patients rated treatment satisfaction using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Treatment Satisfaction-General (FACIT-TS-G) questionnaire.14 This eight-item scale assesses overall feelings about how treatment has gone. The FACIT-TS-G has two subscales (score range, 0 to 32). One subscale is for effectiveness and the other for recommending the treatment. FACIT-TS-G has demonstrated good internal consistency and test-retest reliability in patients with cancer.

FACIT-Spiritual Well-Being.

The FACIT-Spiritual Well-Being questionnaire15,16 is part of the larger FACIT measurement system that assesses multidimensional health-related quality of life. FACIT-Spiritual Well-Being is a valid and reliable 12-item measure that contains three subdomains (peace, meaning, and faith) used to assess spiritual well-being in individuals with cancer and other chronic illnesses and is the most widely used measure of spiritual well-being among patients with cancer. Questions are answered on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Distress Thermometer.

Patients completed the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Distress Thermometer,17 a scale that ranges from 0 (no distress) at the bottom of a thermometer graphic to 10 (extreme distress) at the top. The Distress Thermometer is the most extensively studied measure of emotional distress in patients with cancer and demonstrates appropriate sensitivity and specificity in this population.

Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey.

The Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey is a 19-item questionnaire that measures how often specific forms of social support are available to an individual on a scale from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time).18 It is designed for easy administration to patients with chronic illness.

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations (SDs) for continuous data and frequencies and proportions for categorical data, were calculated for all study measures. Independent t tests were used to test for group differences in continuous measures if the comparison groups had sufficient data, whereas Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables. Two post hoc comparisons were performed to compare concordance with years of provider experience and stage of disease. If the data were sparse, Wilcoxon two-sample tests were used for continuous independent variables. Logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between patient and provider answers in concert with independent measures. SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

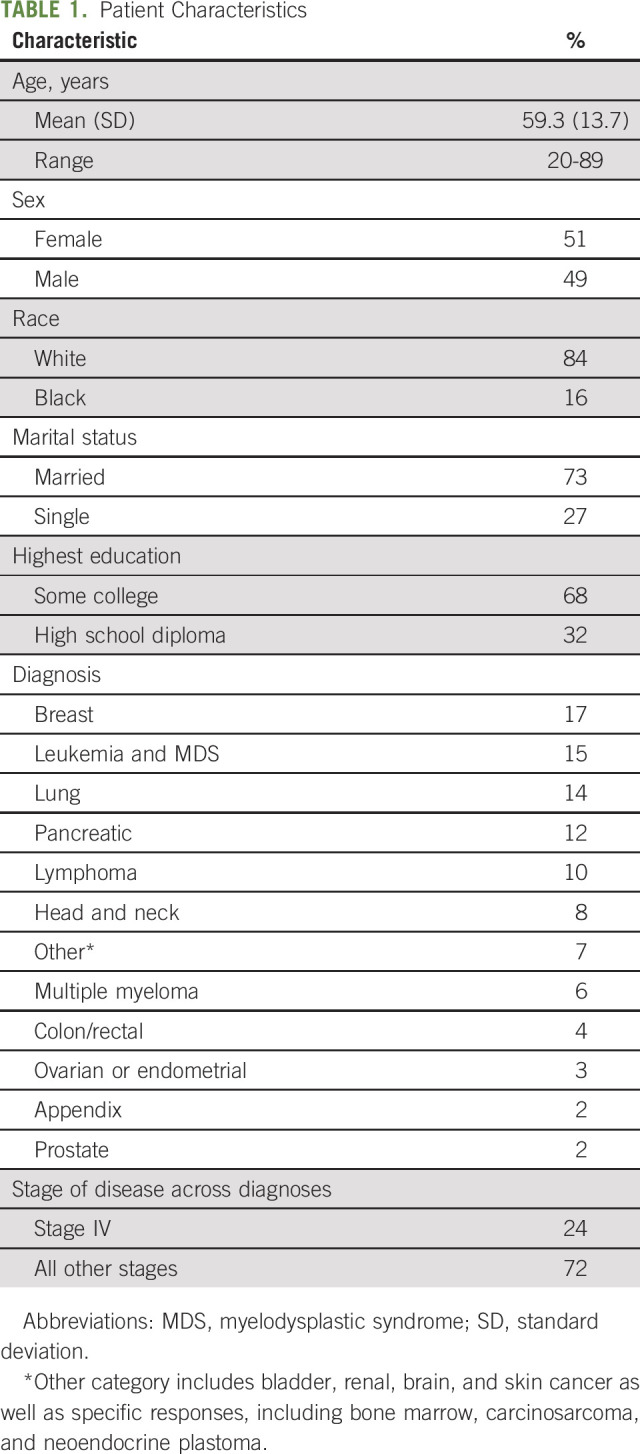

One hundred patients with cancer, fifty-one of whom were female, at a comprehensive cancer center in the southeastern United States participated. Their mean age was 59.3 years (SD, 13.7 years). The majority of patients were white (84%; 16% African American), married (73%), parents (85%), and college educated (68%). More than 20 cancer types were represented, the most common being breast (n = 17), leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome (n = 15), and lung (n = 14). Twenty-four patients were diagnosed with stage IV disease (n = 72 for all other stages).

Thirty-four providers participated, including 26 medical, five radiation, and three surgical oncologists. Provider experience ranged from 2 to 38 years (mean, 16 years; SD, 10 years; median, 15 years). Sixty-five of 100 provider surveys were completed on the same day as the patients’. The mean completion time difference was 5 days (SD, 16 days); 84 of the 100 provider surveys were completed within 7 days.

Concordance Questionnaire (Goals and Understanding of Treatment)

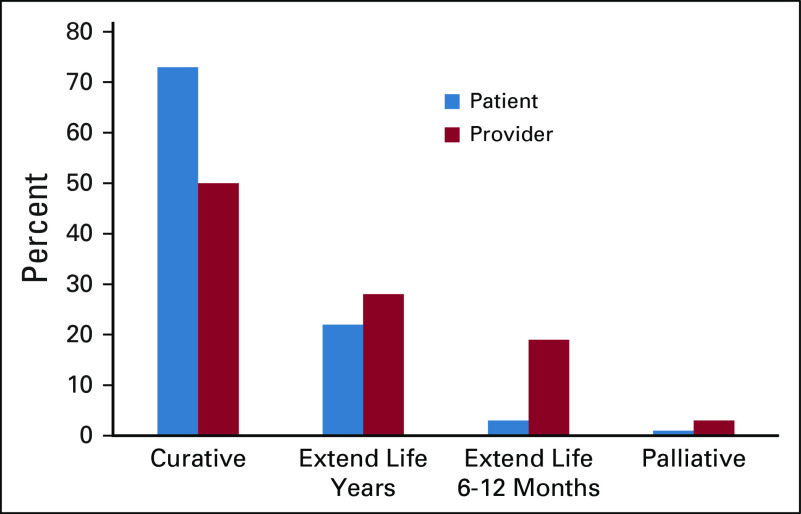

Patients and providers agreed 61% of the time about the intent of treatment (ie, curative, extend life several years, extend life for 6 to 12 months, palliative; Fig 1). In cases of nonagreement, only three patients were less optimistic about the goal of their therapy compared with their provider. Correspondingly, 35 patients (36%) were more optimistic than their providers’ response indicated about the goal of the therapy. Most patients (n = 72; 73%) reported that their treatment was intended to cure their cancer completely (compared with 50% of providers who believed the goal was curative), extend life for several years (n = 22 [22%] v 28% of providers), extend life for 6 to 12 months (n = 3 [3%] v 19% of providers), or not extend life but make them more comfortable (n = 1 [1%] v 3% of providers). Patients who believed that their treatment was curative scored significantly higher on spirituality (P = .02) than those who reported noncurative intent. No relationship was noted between patient-provider agreement about the intent of treatment and income (P = .15), race (P = .39), marital status (P = .50), or education (P = .27). We observed no relationship between provider years of practice and concordance (P = .74). We compared stage IV disease with all other stages and found no relationship with discordance (P = .22). Eleven (46%) of 24 patients with stage IV disease were more optimistic than their providers; 23 (32%) of 72 patients without stage IV disease were more optimistic.

Fig 1.

Patient and provider agreement about the intent of treatment.

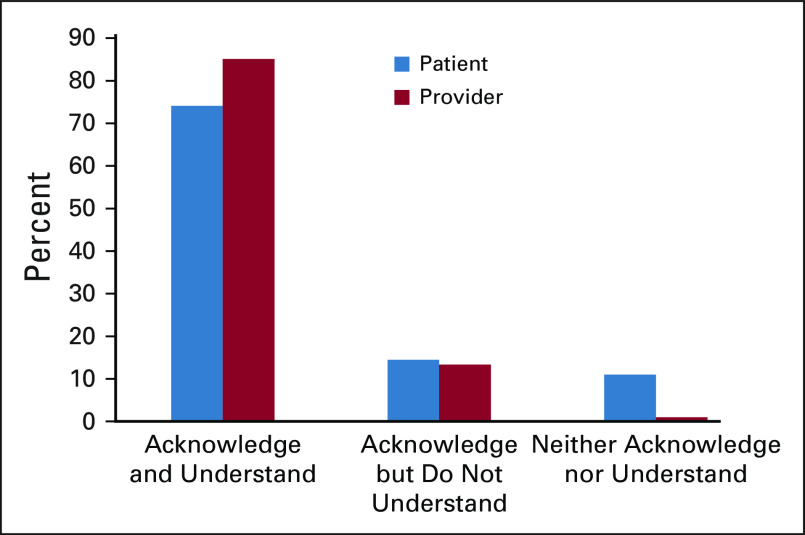

Patients and providers agreed 69% of the time about the patient’s acknowledgment and understanding of the adverse effects (Fig 2). The providers endorsed the item “The patient seemed to acknowledge and understand the side effects” 85% of the time, whereas the patients endorsed the same item 74% of the time. Seven patients (7%) chose “I really did not know or understand the side effects before I started the treatment.” No clinicians indicated that the patient did not understand the treatment. When the clinician had doubts about the patient’s understanding of treatment adverse effects, 8% of the patients reported that they knew the adverse effects. Twenty-three percent of the time, patients indicated that they did not understand the associated adverse effects, yet their providers perceived them as comprehending. Patients who reported an understanding of the likely adverse effects endorsed significantly lower scores on the Distress Thermometer (mean, 2.5) than those who endorsed not understanding the associated adverse effects (mean, 4.1; P = .008). Those with a distress score of 4 or greater (n = 36) also had comparatively lower social support scores than those with a score of less than 4 (mean, 83.3 [SD, 22.7] v 93.5 [SD, 9.4]; P = .014).

Fig 2.

Patient and provider agreement about the patient’s acknowledgment and understanding of adverse effects.

Treatment Satisfaction

Treatment satisfaction was high, with 93% of participants reporting overall treatment ratings as good, very good, or excellent. Compared with what they expected, 81% reported that their treatment was about the same as anticipated, a little better, or a lot better. Only 1% reported that they would not recommend this treatment. Scores were similarly high for effectiveness of treatment, regardless of whether the patient agreed with their provider on the intent. Those in agreement (mean score, 74.8; SD, 25.2) were only slightly higher than those not in agreement (mean score, 69.3; SD, 22.0; P = .18). With respect to recommending treatment, scores were high both for those not in agreement (mean, 91.9; SD, 18.7) and for those in line with providers’ assessments (mean, 90.8; SD, 18.7; P = .78; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

DISCUSSION

Results confirmed two of our three hypotheses. A discrepancy existed between a significant percentage of patients’ and providers’ view of the intent and adverse effects of treatment, and lower patient-provider concordance was associated with increased patient distress. When patients and providers disagreed, the patients were almost always more optimistic about the intent of treatment. Many believed that the intent was to cure their disease rather than to extend life. These differences could constitute true miscomprehension or optimism on the part of patients. Some researchers have suggested that optimism serves as a protective factor against distress. In a similar patient population, greater optimism was associated with less negative illness appraisal.19 However, treatment decision making on the basis of an inaccurate understanding of prognosis or treatment-induced symptom burden may result in unrealistic expectations. In our study, a substantial percentage of patients (36%) anticipated a more favorable outcome than did their providers. Fortunately, communication with both realism and hope is possible.20

For a variety of reasons, we know that what is said is not always incorporated.21 On the contrary, message delivery can be vague or confusing to recipients, which also leads to discordance. One can imagine that misunderstandings between patients and providers could result in violated expectations, reduced satisfaction, or even the election of undesired treatment. Yet the majority of our participants, including those exhibiting discordance, were highly satisfied. High satisfaction could be attributable to a number of factors, including strong provider attentiveness, measurement timing, the limitations of instrumentation, or the ability of imperfect concordance and high satisfaction with providers to coexist. Sapir et al22 similarly found high satisfaction ratings in the context of discordant understanding.

Our data show instructive patterns. First, there is no evidence of difference in concordance on the basis of stage IV disease (v others). Of the 24 patients with stage IV disease, nearly one half (n = 11) were more optimistic than providers, whereas the remaining 13 were in agreement. Although this finding highlights variables other than stage of disease that contributed to the discordance, it also suggests that a significant percentage of our patients with stage IV disease were not aware of care intent. Patients who did not understand treatment adverse effects reported higher distress scores. In addition, those with higher distress scores had lower social support. Screening on distress and social support indicators could alert clinicians to patients who may need additional supportive services and education. Communication strategies, such as ask-tell-ask, could facilitate dialogue greatly by avoiding reliance on encoding assumptions.23 This three-step approach can be used to assess patient understanding (ask), clarify misperceptions (tell), and invite subsequent discussion (ask).

We found no relationship between years of provider experience and patient-provider agreement rates. Perhaps experience influences communication so subtly that it is difficult to capture in the form of agreement on intent and adverse effects of treatment. Also likely is that each provider has honed his or her communication style, and this style is more effective than years of experience. Despite high rates of discordance, the high satisfaction ratings suggest a high level of comfort with providers.

This study demonstrated that the collection of data from both patients and providers in quick succession is feasible. In addition to continuing to teach providers-in-training about active listening and intentional responding, the implementation of clinic-based data monitoring systems to increase awareness of discrepancies in understanding and dissatisfaction could improve the quality of care. Such systems could ask all patients to opt in or out of research upon care initiation and thereby reduce provider accrual bias. Our patient population was relatively well educated, with 68% indicating some college education. This comparatively high education level may be reflective of a greater percentage of prospective participants with less education who did not consent to the studies, which thereby affects representativeness.24 In consideration of this relatively high patient education level, of additional interest is whether we would have observed even lower concordance rates within dyads in which patients have less education, language barriers, cultural differences, and so forth.

In addition to exploring concordance in various patient groups in which a higher preponderance of communication barriers may exist, future studies could gauge whether patient concordance, distress, and satisfaction levels change over time through a longitudinal investigation of trajectories. Although the concordance rates of patients with stage IV disease versus all other stages did not differ significantly, researchers should explore the contributions of disease stage to distress and concordance within larger sample sizes. In addition, future studies should explore the etiology of communication impasses, interventions that incorporate clinic-acquired feedback, screening efforts for variables associated with concordance (eg, distress, social support), and the impacts of ongoing training for providers. Finally, the increasing availability of Web-based information can result in a triangular informational flow among providers, patients, and the Internet, which thereby warrants more research as it relates to concordance and distress.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample size was small and included patients from one institution at one particular point in their treatment continuum. Second, the study was open to a heterogeneous group, including participants who were receiving radiation, chemotherapy, and surgical interventions as well as participants at differing stages of treatment. Our sample size did not allow for comparison of patients who received different treatment interventions. Third, it is possible that patients who have received more treatment may have more informed perspectives of the range of adverse effects and the associated impact compared with those just initiating. Fourth, ratings of distress, satisfaction, and understanding of adverse effects likely are dynamic and fluctuate on the basis of symptom burden. Ratings were captured at one moment within treatment trajectories. Possibly, patients less satisfied with their care declined participation in the study altogether. Finally, the concordance questionnaire we used has not been validated in any other study. Future studies should continue to explore optimal means of measuring concordance.

In conclusion, our findings suggest the need for repeated patient education efforts before and during treatment. Approximately one third of the patient population maintained expectations about the intent of treatment that differed from those of their providers or did not comprehend the anticipated adverse effects. Providers can ask patients directly about their understanding and implement clinic-based feedback systems and screening to record other variables associated with discordant expectations and facilitate the basic task of communicating clearly what patients often are not prepared to hear or understand. Education on the fundamentals of active listening for both patients and providers could result in improved information exchange and mindfulness of what is not heard.

APPENDIX

Patient Questionnaire

A Health Services Research Study to Evaluate Communication Effectiveness in Oncology Treatment

ORIS-assigned PID: _________________________ Date: ______________________

What is the specific type of cancer you have? ____________________________

-

Your knowledge about your cancer comes from? (check all that apply)

Knowing family members or close friends who had the same cancer.

What doctors and nurses have told me.

Research done by friends and relatives.

My own research.

The Internet.

Other, specify ______________.

-

What best describes the goal of your current treatment?

This treatment is trying to cure my cancer completely.

This treatment is trying to extend my life for several years.

This treatment is trying to extend my life for 6 months to a year.

This treatment will not extend my life but is intended to make me more comfortable and experience less pain.

-

How likely do you think it is that your treatment will accomplish the goal you chose in question 3?

I think it is almost certain to succeed.

While not certain, I think it has some chance to succeed.

I think it is unlikely to succeed.

-

When deciding to get this treatment, how well do you think you understood the likely side effects of the treatment?

I knew and understood the side effects it would likely cause.

I knew the probable side effects but did not really understand them.

I really did not know or understand the side effects before I started the treatment.

-

Which statement best describes the role your family played when decisions about your treatment were made?

You made the decisions with little or no input from your family.

You made the decisions after considering your family’s opinion.

You and your family made the decisions together.

Your family made the decisions after considering your opinion.

Your family made the decisions with little or no input from you.

Not applicable (eg, I don’t have any family).

-

What role did the possible side effects of the treatment play in your decision to get this therapy?

No role; I would have chosen this therapy no matter what the side effects.

I had concerns about the side effects but went ahead with the therapy.

Possible side effects (in this therapy or others) affected my decision regarding my treatment.

Are you doing any other things to treat or help you deal with your cancer (exercising, diet, natural cures, etc)? Yes_____ No ______

-

If yes, circle all that apply

Exercising.

Considering nutritional choices carefully.

Alternative/natural cures.

Other __________________.

-

Considering your cancer, how much longer do you expect to live?

I believe I will live more than 10 years.

I believe I will live 5-10 more years.

I believe I will live 1-5 years.

I believe I will live 6 months to a year.

I believe I will live less than 6 months.

-

What are your expectations about how long you expect to live?

Longer than what the doctors tell me.

About what the doctors tell me.

Shorter than what the doctors tell me.

My doctors have not told me and/or I do not know how to set my expectations as to how long to expect to live.

-

What are your expectations about how long you expect to live?

Longer than what my family and friends say.

About what my family and friends say.

Shorter than what my family and friends say.

I do not know what my friends and family say.

-

Because of your cancer, which of the following have you done or are planning to do? (mark all that apply)

Visit my friends and relatives more.

Take a special vacation or trip.

Update my will or final arrangements.

Other__________________

Provider Questionnaire

A Health Services Research Study to Evaluate Communication Effectiveness in Oncology Treatment

The following questions are for research purposes and are not intended to be legally or medically binding. They will not be reviewed by the patient.

-

How knowledgeable is the patient about his/her disease and treatment?

The patient is well informed about his/her disease and the treatment he/she is receiving.

The patient did not know much about his/her disease or treatment but seemed to understand it when explained.

I am not confident of the patient’s understanding of his/her disease or treatment.

The patient relied upon a family member or friend who appeared to understand the disease and treatment? ____Yes ____No

-

In layperson’s terms, what best describes the intent of the patient’s current therapy?

This treatment is trying to cure the patient’s cancer completely.

This treatment is trying to extend the patient’s life for several years.

This treatment is trying to extend the patient’s life for 6 months to a year.

This treatment will not extend the patient’s life but is intended to make him/her more comfortable and experience less pain.

Pertaining to question 3, what probability do you give the therapy in succeeding? ________%

-

When deciding to get this treatment, how well do you think the patient understood the likely side effects of the treatment?

The patient seemed to acknowledge and understand the side effects.

The patient seemed to acknowledge the side effects but did not seem to really understand them.

The patient did not seem to acknowledge or understand the side effects.

-

In your perception, how much family involvement was there in the treatment decision process?

The decisions were made with little or no input from the patient’s family.

The decisions were made after considering the patient’s family’s opinion.

The patient and his/her family made the decisions together.

The patient’s family made the decisions after considering the patient’s opinion.

The patient’s family made the decisions with little or no input from the patient.

Not applicable (eg, the patient had no family).

I do not know.

-

In your perception, what role did the possible side effects of the treatment play in the patient’s decision to move forward with this therapy?

No role; the patient would have chosen this therapy no matter the side effects.

The patient was initially concerned about the possible side effects but eventually decided to receive the therapy.

The possible side effects (or lack of them) were a significant reason the patient decided to receive this therapy.

I am uncertain what role the side effects played in the patient’s decision.

Are you aware of the patient doing anything else to help treat or manage his/her cancer? Yes______ No_______

-

If yes, mark all that apply

Exercising.

Considering nutritional choices carefully.

Alternative/natural cures.

Other __________________.

-

Considering the patient’s cancer, how much longer do you expect him/her to live?

More than 10 years.

5-10 more years.

1-5 years.

Six months to a year.

Less than 6 months.

-

What is your perception of the patient’s attitude toward his/her prognosis?

More optimistic than me.

Pretty much in line with mine.

More pessimistic than me.

I am unsure what the patient thinks about his/her prognosis.

-

How much support do you perceive the patient has from family and community?

The patient seems well supported by family and community.

The patient seems to be relying on just a few family members or friends.

The patient does not have much support from family or community.

I am not aware of how much support the patient is getting.

Supported by National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant P30CA012197 issued to the Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

Presented at the 14th American Psychosocial Oncology Society Annual Conference, Orlando, FL, February 15-18, 2017.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Katharine E. Duckworth, Robert Morrell, Olivia Riffle, Richard McQuellon

Administrative support: Richard McQuellon

Collection and assembly of data: Katharine E. Duckworth, Aimee Tolbert

Data analysis and interpretation: Katharine E. Duckworth, Gregory B. Russell, Bayard Powell, Mollie Canzona, Stephanie Lichiello, Aimee Tolbert, Richard McQuellon

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Goals and Adverse Effects: Rate of Concordance Between Patients and Providers

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Katharine E. Duckworth

Employment: Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center

Bayard Powell

Honoraria: Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals

Speakers’ Bureau: Celgene, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novartis

Research Funding: Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Novartis, Celator, Incyte

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Novartis, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer

Richard McQuellon

Honoraria: Eli Lilly, Genentech

Speakers’ Bureau: Eli Lilly, Genentech

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Eli Lilly, Genentech

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. : Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 279:1709-17141998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack JW, Walling A, Dy S, et al. : Patient beliefs that chemotherapy may be curative and care received at the end of life among patients with metastatic lung and colorectal cancer. Cancer 121:1891-18972015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cartwright LA, Dumenci L, Siminoff LA, et al. : Cancer patients’ understanding of prognostic information. J Cancer Educ 29:311-3172014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DesHarnais S, Carter RE, Hennessy W, et al. : Lack of concordance between physician and patient: Reports on end-of-life care discussions. J Palliat Med 10:728-7402007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al. : Determinants of patient-oncologist prognostic discordance in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol 2:1421-14262016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lux MP, Bayer CM, Loehberg CR, et al. : Shared decision-making in metastatic breast cancer: Discrepancy between the expected prolongation of life and treatment efficacy between patients and physicians, and influencing factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139:429-4402013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ha JF, Longnecker N: Doctor-patient communication: A review. Ochsner J 10:38-432010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siminoff LA, Step MM: A communication model of shared decision making: Accounting for cancer treatment decisions. Health Psychol 24:S99-S1052005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al. : Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer 113:3459-34662008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engelhardt EG, Pieterse AH, van der Hout A, et al. : Use of implicit persuasion in decision making about adjuvant cancer treatment: A potential barrier to shared decision making. Eur J Cancer 66:55-662016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldzweig G, Abramovitch A, Brenner B, et al. : Expectations and level of satisfaction of patients and their physicians: Concordance and discrepancies. Psychosomatics 56:521-5292015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prouty CD, Mazor KM, Greene SM, et al. : Providers’ perceptions of communication breakdowns in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med 29:1122-11302014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canzona MR, Garcia D, Fisher CL, et al. : Communication about sexual health with breast cancer survivors: Variation among patient and provider perspectives. Patient Educ Couns 99:1814-18202016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peipert JD, Beaumont JL, Bode R, et al. : Development and validation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Treatment Satisfaction (FACIT TS) measures. Qual Life Res 23:815-8242014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. : Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 24:49-582002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterman AH, Reeve CL, Winford EC, et al. : Measuring meaning and peace with the FACIT-Spiritual Well-Being scale: Distinction without a difference? Psychol Assess 26:127-1372014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC, et al. : Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer 103:1494-15022005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL: The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32:705-7141991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumpio C, Jeon S, Northouse LL, et al. : Optimism, symptom distress, illness appraisal, and coping in patients with advanced-stage cancer diagnoses undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum 44:384-3922017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.11.138. Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al: Communicating with realism and hope: Incurable cancer patients’ views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol 23:1278-1288, 2005 [Erratum: J Clin Oncol 23:3652, 2005] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeBlanc TW, Temel JS, Helft PR: “How Much Time Do I Have?”: Communicating prognosis in the era of exceptional responders. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 38:787-7942018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sapir R, Catane R, Kaufman B, et al. : Cancer patient expectations of and communication with oncologists and oncology nurses: The experience of an integrated oncology and palliative care service. Support Care Cancer 8:458-4632000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnett PB: Rapport and the hospitalist. Dis Mon 48:250-2592002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, et al. : Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med 163:83-902003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]