INTRODUCTION

The exponential use of immunotherapy agents in metastatic malignancies with traditionally poor survival outcomes has generated new challenges for physicians. One of the major hurdles in clinical practice is to determine the minimum duration of therapy that will have clinical benefit for patients and will result in stable disease (SD) to sustain long-term responses. The decision regarding when to stop therapy is not easy, and most physicians discontinue therapy after 12 to 24 months, according to data from melanoma and lung cancer trials.1,2 Clinical trials are actively being planned to help understand when it is safe to stop immunotherapy.3 The optimal duration of therapy has not yet been defined, but there is another question: Do checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) remain a viable treatment option upon disease progression after a planned treatment interruption? Evidence is accumulating on balancing the risks and benefits when CPIs are re-administered after immune-related adverse events (AEs) develop,4,5 and on the lack of efficacy when rechallenging after disease progression with the same or a different CPI.6-8 In contrast, there are limited data on the safety and efficacy of re-administering immunotherapy after planned treatment interruption.

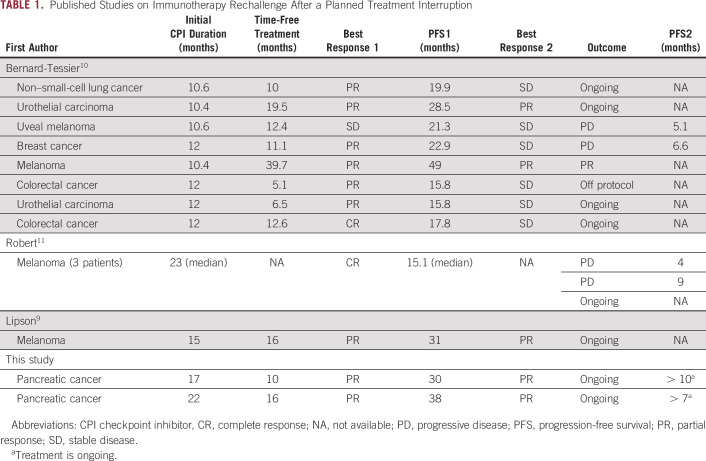

The literature is scarce, but there seems to be efficacy when re-introducing immunotherapy after discontinuing it for reasons other than progressive disease (PD) or development of immune-related AEs (Table 1). Lipson et al9 reported that a patient with melanoma was successfully rechallenged with immunotherapy after discontinuing intermittent dosing with CPIs in the first-in-human phase I study of the anti-programmed cell death protein 1 (anti-PD-1) antibody BMS-936558. That patient received intermittent therapy for approximately 15 months and achieved a partial response (PR), which was maintained during 16 months of therapy. When PD occurred, retreatment was pursued. The patient again achieved a PR, which was maintained for another 16 months during therapy.9 Bernard-Tessier et al10 have published the largest study on this subject to date; eight patients with solid tumors treated with CPIs after a median duration of therapy of 12 months in phase I trials were retreated with the same CPI. Among the eight patients, two (25%) achieved PR, and six (75%) achieved SD. One patient with triple-negative breast cancer and 1 with uveal melanoma achieved PRs after retreatment, but their disease eventually progressed.10 Robert et al11 reported the long-term follow-up of patients with melanoma from the KEYNOTE-001 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01295827) study, who had a complete response (CR) and either continued CPI therapy or discontinued therapy and underwent surveillance. In all, 67 of 91 patients eligible for rechallenge chose to discontinue therapy after a median treatment duration of 23 months and 7 months after CR; four of 67 patients had disease progression, and three were retreated with pembrolizumab. Two of these patients had disease progression after 4 and 9 months, and one was still receiving therapy after 15 months when that article was published.11 More recently, Betof et al12 reported the long-term outcomes of patients with melanoma treated with CPIs, and 78 patients who were retreated with CPIs were included. The median time between discontinuation of initial treatment and retreatment was 6.3 months; only 16 of 78 patients responded to retreatment with either single-agent anti-PD-1 therapy or with combination therapy with anti-CTLA4.

TABLE 1.

Published Studies on Immunotherapy Rechallenge After a Planned Treatment Interruption

In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration approved pembrolizumab for any solid tumor with mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) after PD with previous treatments. This approval was based on cumulative data across five clinical trials with a total of 149 patients who showed high overall response rates to pembrolizumab.13 Only 8 patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) were included in those initial clinical trials 14 and another 22 patients were described in the more recent KEYNOTE-158 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02628067) trial.15 Despite advances in other solid malignancies, metastatic pancreatic cancer still has a dismal prognosis with a 5-year overall survival of less than 10%.16 The prevalence of dMMR in pancreatic cancer is 0% to 1.3%.17,18 Not surprisingly, CPIs alone have limited efficacy in PDAC.19

Here we report the experience at our center with two patients who had dMMR PDAC, treated with immunotherapy and then rechallenged upon PD after a planned treatment holiday. Both patients signed an informed consent stating they have read this article, and they give their permission to publish all the information and images included herein.

CASE PRESENTATION

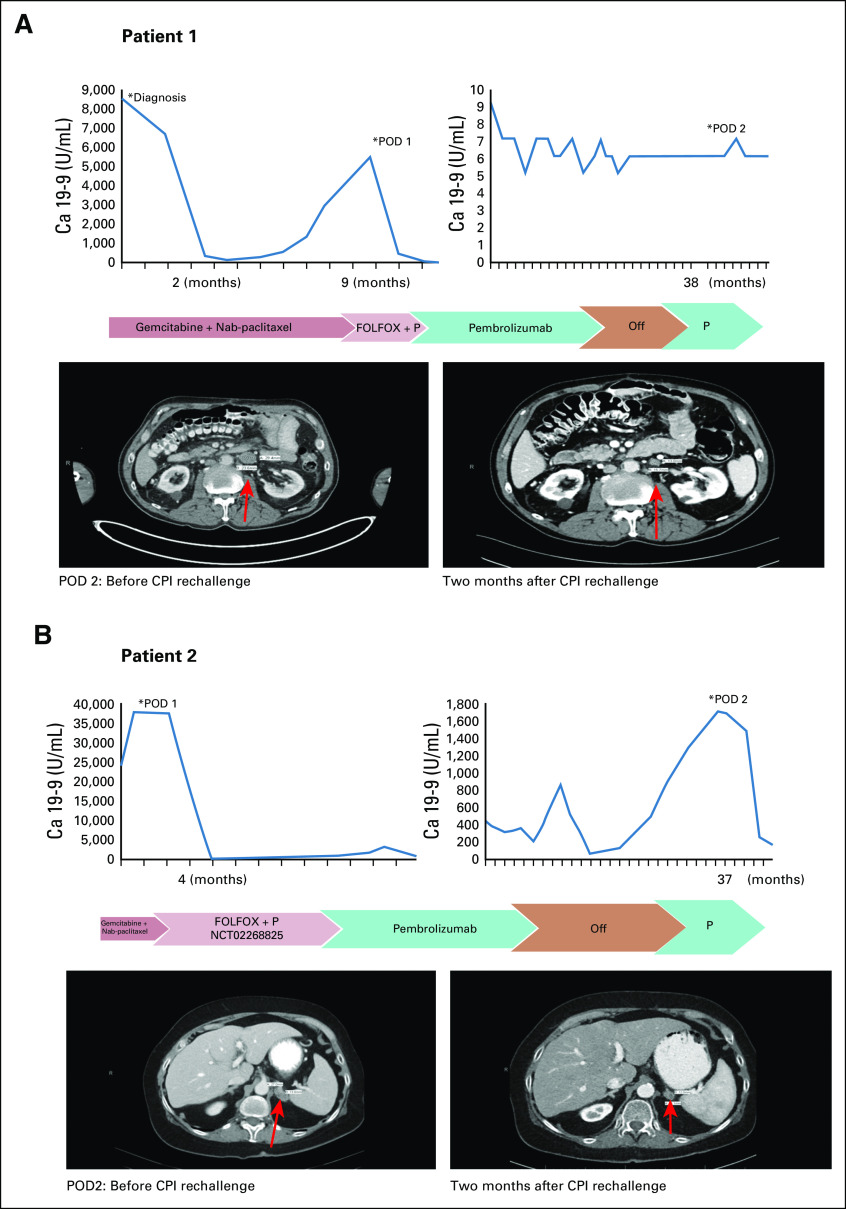

The first patient is a 69-year-old man who was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 2015. He had locally advanced unresectable disease and was treated initially with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. He completed six cycles of therapy with a reduced dose because of toxicity before PD eventually developed. He was hospitalized several times because of duodenal invasion of the pancreatic mass leading to obstruction, but he recovered and restarted treatment 3 months later with oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and fluorouracil (FOLFOX) and pembrolizumab based on high microsatellite instability findings on genetic sequencing of his tumor (Table 2). FOLFOX was added to pembrolizumab because of rapid clinical disease progression. However, after one cycle, he developed a perforated gastric ulcer that required exploratory laparotomy, and FOLFOX was permanently discontinued. Two months after starting immunotherapy, his tumor had radiographic PR, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (Ca 19-9) decreased from 5,503 to 17 U/mL. The radiographic response (PR) plateaued after 13 cycles of pembrolizumab and after Ca 19-9 normalized. He had SD for 17 months, at which point treatment was discontinued. He had periodic imaging for 10 months, at which time he was found to have progression of para-aortic lymphadenopathy. Subsequent biopsy confirmed metastatic PDAC. Interestingly, his tumor markers did not increase at that time (Fig 1A). In light of his previous good response, pembrolizumab was restarted. A computed tomography (CT) scan at 2 months after retreatment showed a PR (Fig 1A), and at 6 months, CT scans showed a sustained radiographic response. He did not develop any grade 3 to 4 immune-related AEs at any point. He still receives CPIs with continuing response approximately 10 months later.

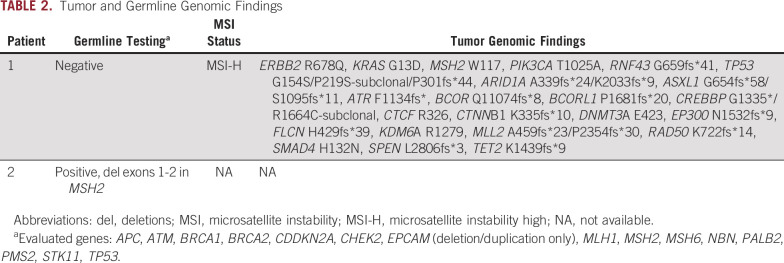

TABLE 2.

Tumor and Germline Genomic Findings

FIG 1.

Tumor marker trend, treatment timeline, and imaging for (A) patient 1 and (B) patient 2 at the time of immunotherapy rechallenge. Arrows indicate the sites of disease progression (para-aortic lymphadenopathy for patient 1 and left adrenal metastasis for patient 2). Ca 19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; FOLFOX, oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and fluorouracil; P, pembrolizumab; POD, progression of disease.

The second patient is a 64-year-old woman with Lynch syndrome who was diagnosed with metastatic dMMR pancreatic cancer in 2016. She received nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for one cycle before she presented for a second opinion at our center. She then enrolled in a clinical trial (ClinicalTrils.gov identifier: NCT02268825) that used FOLFOX plus pembrolizumab. CT scans at 3 months showed response in the primary tumor in the body and tail of the pancreas as well as liver metastases. Baseline Ca 19-9 was 37,576 U/mL, and it improved to 279 U/mL. Oxaliplatin was discontinued after cycle 7 because of persistent neuropathy, and fluorouracil plus pembrolizumab were continued for five cycles. At that time, a protocol amendment mandated the addition of celecoxib to the treatment. Our patient was receiving therapeutic anticoagulation for extensive deep vein thrombosis. Because adding celecoxib would significantly increase her bleeding risk, she was taken off protocol to continue single-agent pembrolizumab under an expanded access program. She continued to receive pembrolizumab for 22 months before treatment was discontinued. At that time, she had a few subcentimeter hypodensities in the liver and a CR in the pancreatic tumor with only some soft tissue stranding around the celiac artery. After 16 months, she experienced PD with increasing Ca 19-9 levels as well as a new left adrenal gland lesion (Fig 1B). Biopsy of the lesion revealed metastatic adenocarcinoma consistent with pancreatic primary. Pembrolizumab was re-initiated. She attained radiographic PR to therapy, as well as improvement in Ca 19-9 levels (Fig 1B). She did not develop any grade 3 to 4 immune-related AEs.

DISCUSSION

Following the success of pembrolizumab in dMMR cancers, numerous CPIs have been approved for a variety of indications.1,20,21 CPIs have a favorable toxicity profile compared with cytotoxics; however, some patients may develop life-threatening immune-related toxicities.22

There is a paucity of literature that addresses the optimal duration of therapy. Unlike cytotoxic chemotherapy, PD-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors disrupt tumor immune evasion by restoring the T-cell function.23 The first long-term survival data from patients treated with CPIs are now becoming available, and recent evidence shows that some patients with metastatic disease attain durable responses to CPIs with survival rates of more than 5 years.24 These data suggest that in certain patients, alterations to the tumor immune microenvironment and host adaptive antitumor immunity may be irreversible and long-lasting. The ideal duration of therapy required to achieve this effect has not been established, nor have any tumor or host biomarkers been established to identify these patients. Although PD-L1 expression by the infiltrating immune cells may be predictive of some responses at initial therapy or at re-induction of that therapy,9 it has not been described in all patients and it certainly varied across different histologies. Unfortunately, we could not obtain PD-L1 expression levels in our patients because of the limited tissue in biopsy samples. Clinically, the interval between treatment discontinuation and rechallenge could have predictive value. Although it was not seen in all cases described in the literature (Table 1), most patients who responded to CPIs a second time had long intervals of > 10 months. This is consistent with our patients and could be an explanation for the low responses in the recent melanoma study12 (the interval was only 6.3 months). However, in that study,12 patients with PD on first treatment were also included. Finally, one thing that was consistent across the literature was that the quality of initial response (CR, PR, or SD) does not necessarily predict the patients who will benefit from CPI rechallenge.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of patients with dMMR pancreatic cancer who attained a response to treatment rechallenge with CPIs after a treatment holiday. This adds to the growing literature that shows the benefit of this approach. Although the response rates seem lower on re-induction, rechallenging with CPIs may be safe and to some degree efficacious.

SUPPORT

Supported by National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support Grant No. P30CA042014.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Vaia Florou, Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Financial support: Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Administrative support: Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Provision of study materials or patients: Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Collection and assembly of data: Vaia Florou, Kristin E. Barber, Jenna N. Mastroianni, Courtney C. Cavalieri, Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Data analysis and interpretation: Vaia Florou, Christopher Nevala-Plagemann, Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/po/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Kristin E. Barber

Speakers' Bureau: Merck

Courtney C. Cavalieri

Honoraria: Pharmacy Times Continuing Education

Ignacio Garrido-Laguna

Consulting or Advisory Role: Array BioPharma, Eisai

Research Funding: Novartis (Inst), Ignyta (Inst), Halozyme Therapeutics (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), NewLink Genetics (Inst), MedImmune (Inst), Eli Lilly (Inst), Incyte (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), OncoMed Pharmaceuticals (Inst), ARMO Biosciences (Inst), Glenmark Pharmaceuticals (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): Post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 20:1239-12512019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. : Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 378:2078-20922018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerriero JL, Thaxton J, Bartkowiak T, et al. : 10.1186/s40425-018-0434-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Sbeih H, Ali F, Naqash AR, et al. : Immune-mediated colitis after resumption of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Clin Oncol 372019. (suppl; abstr 2577) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonaggio A, Michot JM, Voisin AL, et al. : Evaluation of readministration of immune checkpoint inhibitors after immune-related adverse events in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 5:1310-13172019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe H, Kubo T, Ninomiya K, et al. : The effect and safety of an immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in non-small cell lung cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 49:762-7652018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saleh K, Khalifeh-Saleh N, Kourie HR: Is it possible to rechallenge with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors after progression? Immunotherapy 10:345-3472018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martini DJ, Lalani AA, Bossé D, et al. : Response to single agent PD-1 inhibitor after progression on previous PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors: A case series. J Immunother Cancer 5:66.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipson EJ, Sharfman WH, Drake CG, et al. : Durable cancer regression off-treatment and effective reinduction therapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin Cancer Res 19:462-4682013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernard-Tessier A, Baldini C, Martin P, et al. : Outcomes of long-term responders to anti-programmed death 1 and anti-programmed death ligand 1 when being rechallenged with the same anti-programmed death 1 and anti-programmed death ligand 1 at progression. Eur J Cancer 101:160-1642018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert C, Ribas A, Hamid O, et al. : Durable complete response after discontinuation of pembrolizumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 36:1668-16742018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Betof Warner A, Palmer JS, Shoushtari AN, et al. : Long-term outcomes and responses to retreatment in patients with melanoma treated with PD-1 blockade. J Clin Oncol 38:1655-16632020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan L, Zhang W: Precision medicine becomes reality-tumor type-agnostic therapy. Cancer Commun (Lond) 38:6.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. : Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357:409-4132017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, et al. : Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with noncolorectal high microsatellite instability/mismatch repair-deficient cancer: Results from the phase II KEYNOTE-158 study. J Clin Oncol 38:1-102020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:7-342019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eso Y, Shimizu T, Takeda H, et al. : Microsatellite instability and immune checkpoint inhibitors: Toward precision medicine against gastrointestinal and hepatobiliary cancers. J Gastroenterol 55:15-262020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu ZI, Shia J, Stadler ZK, et al. : Evaluating mismatch repair deficiency in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: Challenges and recommendations. Clin Cancer Res 24:1326-13362018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Reilly EM, Oh DY, Dhani N, et al. : A randomized phase 2 study of durvalumab monotherapy and in combination with tremelimumab in patients with metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (mPDAC): ALPS study. J Clin Oncol 362018. (suppl; abstr 217) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. : Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for PD-L1-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1823-18332016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. : Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 376:1015-10262017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martins F, Sofiya L, Sykiotis GP, et al. : Adverse effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors: Epidemiology, management and surveillance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 16:563-5802019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. : PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 515:568-5712014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. : Five-year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 381:1535-15462019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]