PURPOSE:

The primary aim of this study was to determine the attitudes and beliefs of hematology and medical oncology (HMO) fellows regarding palliative care (PC) after they completed a 4-week mandatory PC rotation.

METHODS:

The PC rotation included a 4-week standardized curriculum covering all PC domains. HMO fellows were provided educational materials and attended all didactic sessions. All had clinical rotation in an acute PC unit and an outpatient clinic. All HMO fellows from 2004 to 2017 were asked to complete a 32-item survey on oncology trainee perception of PC.

RESULTS:

Of 105 HMO fellows, 77 (73%) completed the survey. HMO fellows reported that PC rotation improved assessment and management of symptoms (98%); opioid prescription (89%), opioid rotation (78%), and identification of opioid adverse effects (87%); communication with patients and families (91%), including advance care planning discussion (88%) and do-not-resuscitate discussion (88%); and they reported comfort with discussing ethical issues (74%). Participants reported improvement in knowledge of symptom assessment and management (n = 76; 98%) as compared with efficacy in ethics (n = 57 [74%]; P = .0001) and for coping with stress of terminal illness (n = 45 [58%]; P = .0001). The PC rotation educational experience was considered either far better or better (53%) or the same (45%) as other oncology rotations. Most respondents (98%) would recommend PC rotations to other HMO fellows, and 95% felt rotation should be mandatory.

CONCLUSION:

HMO fellows reported PC rotation improved their attitudes and knowledge in all PC domains. PC rotation was considered better than other oncology rotations and should be mandatory.

INTRODUCTION

Palliative care (PC) is established as an essential and integral part of cancer care.1-4 Prior studies suggest benefits of PC include significantly reducing physical symptoms, as well as alleviating of psychosocial distress, improving quality of life, end-of-life quality-care outcomes, and cost of care.4-12 Despite rapid growth in the PC programs for patients with cancer in the hospital and in community settings, there is an important lag in the corresponding growth of well-trained professionals in PC. According to a report from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, the demand for hospice and PC physicians is more than double the supply.13 Since the recognition of hospice and PC as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in 2006 and accreditation of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (HPM) fellowship to qualify for certification starting in 2012, the number of graduates entering HPM has increased.13,14 However, there is still limited enthusiasm among policymakers to completely incorporate HPM in medical school and medical subspecialty curricula. Several studies have shown the benefits of PC rotation among medical students, residents, and fellows.15-18 The Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education issues requirements to incorporate PC competencies in the curriculum of hematology and medical oncology (HMO) fellowship programs. The competencies include management of anxiety, depression, pain, and PC, including hospice and home care.19 However, there are limited published data regarding the adherence to Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education guidelines by oncology fellowships programs.

Furthermore, ASCO recommends the integration of PC with active cancer treatments into standard oncological practice for patients with early or advanced cancer and their caregivers.3,4 Benefits of this early integration include early identification and management of PC needs, enhanced patient-physician communication, and overall better patient experience. In addition, the knowledge and skills facilitate provision of primary PC and reduce the strain on the limited specialist PC team currently available. However, training in PC among various medical specialties, including HMO fellows, has been inconsistent, with only a few academic oncology programs offering mandatory training and others offering it as an optional rotation. The duration of rotations is also variable.

In a consensus among international experts on the integration of oncology and PC, it was recommended that a 1-month rotation by oncologists in PC is ideal.20 They believe a clinical rotation helped oncologists gain knowledge of basic symptom assessment and management, communication and understanding of an appropriate PC referral, and establishment of a cohesive working relationship with the PC team. However, only a few institutions have a mandatory rotation of oncology trainees in PC as part of their training program.21 In a national survey by Buss et al,22 only 26% of oncology fellows completed a PC rotation, with no more than 33% receiving education on various PC topics such as opioid rotation, 23% able to perform opioid conversions, 32% receiving education on assessing and managing depression at end of life, 19% having had mandatory PC rotations, and 7% having had elective PC rotations. Furthermore, most rated the quality of education inferior to overall oncology training. In similar study by Thomas et al,23 approximately 44.9% of participants completed a PC rotation and reported better teaching of pain management, communicating a poor prognosis, and conducting timely hospice referrals. However, the participants also rated their oncology training as being better than end-of-life training. In both studies, it was concluded that HMO fellows were still inadequately prepared to provide PC to their patients, and there was a room for improvement in the quality of PC training for HMO fellows.

At The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (UT MDACC), PC was established in 1999 and started fellowship training program in 2000. Since 2004, oncology fellows in UT MDACC have a 1-month mandatory rotation in PC. One concern when the mandatory rotation started was that most HMO programs encourage their trainees to seek clinical or translational research during their fellowship. Subsequently, fellows lean more toward these tracks and may perceive PC as an easier, less stressful rotation.

Few studies have evaluated the attitudes and knowledge of HMO fellows after the PC rotation. Until 2017, 131 oncology trainees successfully completed PC rotation through the UT MDACC program. Here, we report the results of a survey of these oncology fellows. The primary objective of this survey was to determine the attitudes and perception of improved knowledge and skills in PC of HMO fellows who had a 4-week mandatory rotation in PC. We also examined the pattern of patient referral to PC of PC-trained oncology fellows and aimed to understand the associations between demographic factors and HMO fellows’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills in PC.

METHODS

During this rotation, HMO fellows are provided a 4-week curriculum encompassing physical, psychosocial, and spiritual domains of PC, including communication skills, symptom management, and advanced care planning. The rotation is divided into the inpatient Acute Palliative Care Unit and the outpatient Supportive Care Center, and work with a multidisciplinary team including chaplain, counselors, psychologists, social worker, nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and clinical pharmacists. In addition to receiving standard educational material, they attend didactic sessions of weekly and monthly journal clubs, weekly fellows and faculty case rounds, weekly department chair case-discussion rounds, and weekly departmental grand rounds (Data Supplement). Aside from these, they also received regular bedside clinical teaching.

To be eligible to participate in the survey, the participants were to have trained in the oncology fellowship at UT MDACC and completed the mandatory 1-month rotation. The list of all medical oncology fellows (N = 131) who completed a 4-week rotation in PC in the UT MDACC in Houston, Texas, was identified through fellowship rotation records. An e-mail invitation was sent to all eligible fellows to participate in an online survey. The survey responses were e-mailed directly to our data manager, who deidentified them. During the survey period, the data manager sent weekly e-mail reminders for 6 weeks to eligible fellows to complete the survey. Fellows were reassured their responses would be anonymous and would not affect their clinical practice or their referral practice with the PC service.The survey was composed of 32 questions (Data Supplement) and was developed by palliative and oncology specialists at UT MDACC who had expertise in education, competencies, and learners’ evaluation. Some of the questions were adapted from previously published studies of oncology trainee perception to assess attitudes and beliefs toward PC.22-24 This study was approved by the UT MDACC institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies for categorical data and mean, standard deviation, and range for continuous variables were used to analyze the data. χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to test differences to each question between and among groups. The McNemar test was used to compare different proportions of answering “agree” to two different questions. All computations were carried out in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

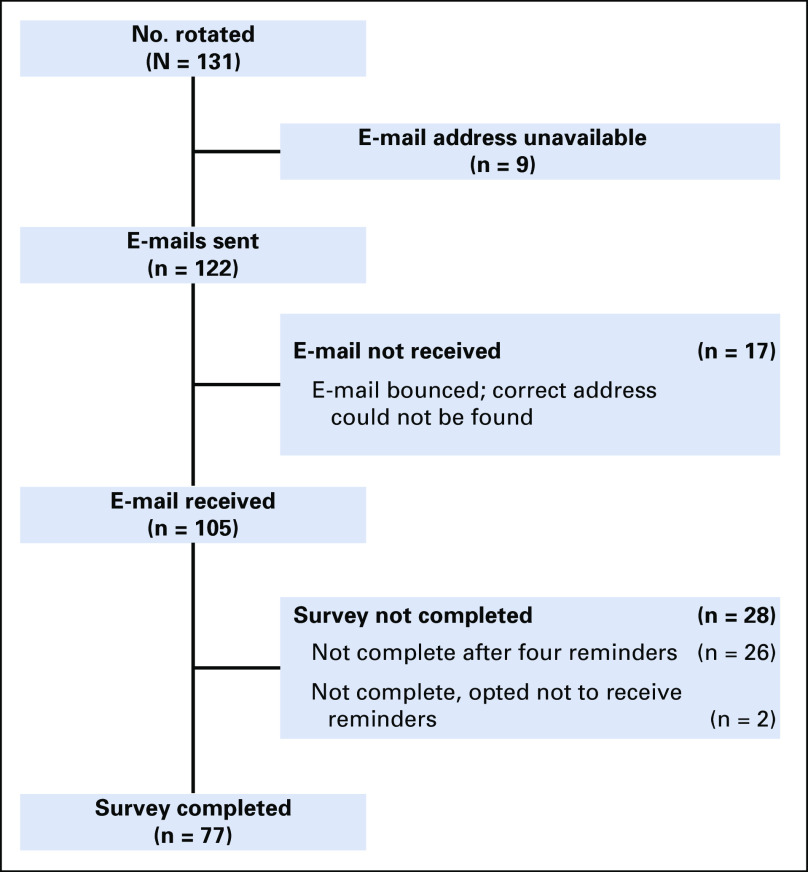

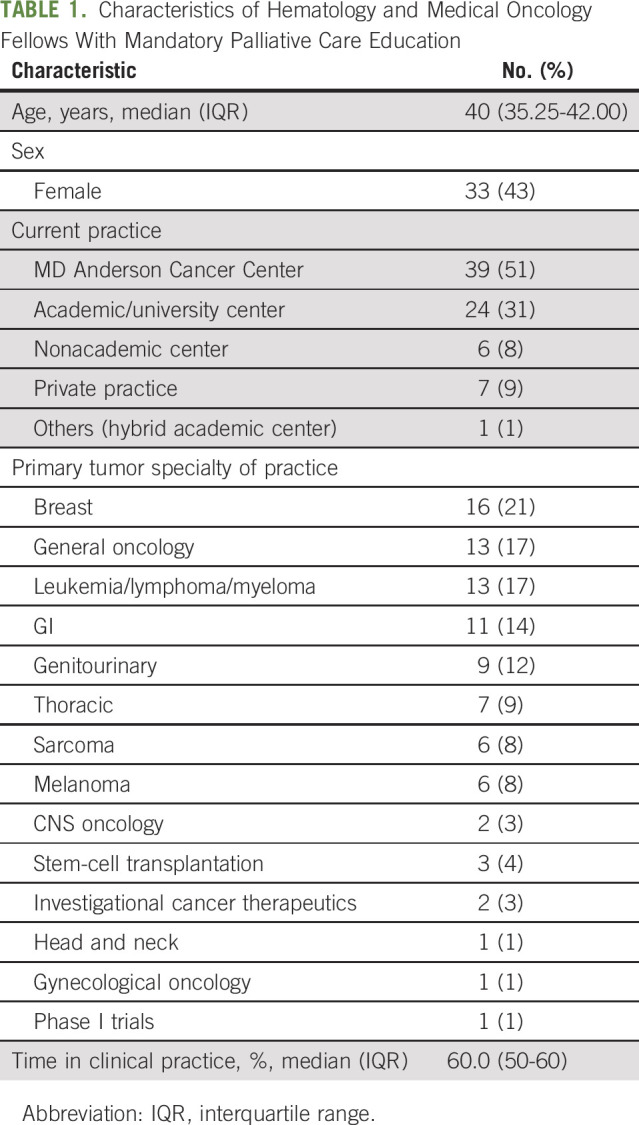

Of 105 eligible fellows, 77 (73%) completed the survey (Fig 1). Twenty-six of the total 131 HMO fellows (20%) did not have contact information on record, or their e-mail addresses were unreachable. Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of respondents. Respondents were a median of 40 years old, 43% were female, a median of 60% of time was spent in clinical practice, and 64 of the 77 respondents (83%) practiced in an academic setting.

Fig 1.

Survey flow and responders.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellows With Mandatory Palliative Care Education

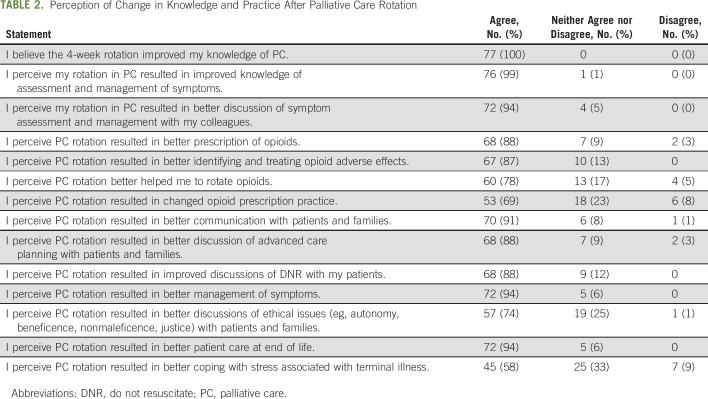

Table 2 reports knowledge and practice changes perceived after the PC rotation. All respondents (n = 77) though the 4-week PC rotation improved their knowledge about PC. Respondents perceived improvement in assessment and management of symptoms (n = 76; 99%); discussion of symptom assessment and management with colleagues (n = 72; 94%); better opioid prescription (n = 68; 88%), identifying and treating opioid adverse effects (n = 67; 87%), opioid rotation (n = 60; 78%), and change in opioid prescription practice (n = 53; 69%); communication with patients and families (n = 70; 91%), discussion of advanced care planning (n = 68; 88%) and do-not-resuscitate preferences (n = 68; 88%); management of symptoms (n = 72; 94%); discussion of ethical issues (n = 57; 74%); providing end-of-life patient care (n = 72; 94%); and coping with stress associated with caring for patient with terminal illness (n = 45; 58%).

TABLE 2.

Perception of Change in Knowledge and Practice After Palliative Care Rotation

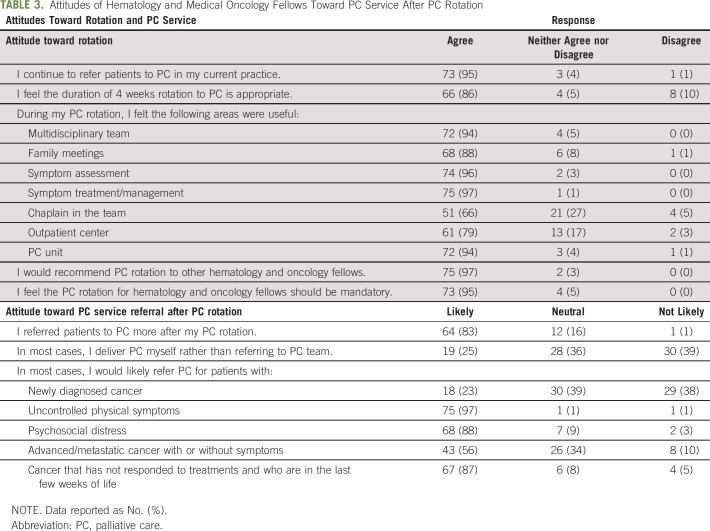

Table 3 lists the attitudes toward PC after the mandatory rotation. Most (n = 73; 95%) reported they are likely to refer patients to PC in their current practice, with 64 (83%) reporting they were more likely to refer patients to PC after the rotation. Patients respondents were likely to refer to PC included those with uncontrolled physical symptoms (n = 75; 97%); psychosocial distress (n = 68; 88%); disease that did not respond to cancer treatments and who are in their last few weeks of life (n = 67; 87%); and with advanced or metastatic cancer with or without symptoms (n = 43; 56%). Of the 77 respondents, 66 (86%) felt 4 weeks is an appropriate duration of rotation and 73 (95%) said the rotation should be mandatory. Among those who disagreed that 4 weeks is an appropriate duration, five (7%) recommended less than 4 weeks and another five (7%) recommended more than 4 weeks. Most respondents (n = 75; 97%) would recommend PC rotation to other HMO fellows. The following are some areas the HMO fellows thought were useful during the PC rotation: multidisciplinary team (n = 72; 94%); family meetings (n = 68; 88%); symptom assessment (n = 74; 96%); symptom management (n = 75; 97%); having a chaplain on the team (n = 51; 66%); outpatient center (n = 61; 79%); and PC unit (n = 72; 94%). Approximately half of respondents (n = 41; 53%) perceived the PC rotation to be better compared with other mandatory rotations and 35 (46%) perceived it was neither better nor worse.

TABLE 3.

Attitudes of Hematology and Medical Oncology Fellows Toward PC Service After PC Rotation

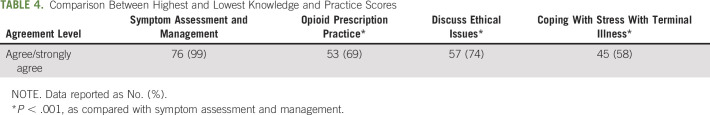

Compared with perceived improvement in symptom assessment and management (n = 76; 99%), there was a significantly lower perception of improvement in areas of change in opioid prescription practice, discussing ethical issues, and coping with stress with terminal illness (Table 4). Comparing responses by sex, significant differences were found in female fellows’ perception of improved opioid rotation compared that of with male fellows (37% v 63%, respectively; P = .0271) and change in opioid prescription practice (32% v 68%, respectively; P = .0123). There were no significant differences when age groups were compared.

TABLE 4.

Comparison Between Highest and Lowest Knowledge and Practice Scores

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the perception of HMO fellows regarding their mandatory rotation to PC during their fellowship training at a comprehensive cancer center. Our findings suggest a mandatory rotation can be highly beneficial when offered with a structured and comprehensive curriculum including rotations in inpatient and outpatient clinical settings. The rotation was perceived as beneficial in terms of attitudes and knowledge of different PC domains, specifically assessment and management of symptoms, including pain. Respondents rated PC rotation better or same compared with other oncology rotations. PC rotation was recommended as mandatory for all HMO fellows.

In contrast to studies by Buss et al22 and Thomas et al,23 the results of our survey showed that more than 60% of fellows perceived a better ability to prescribe opioids, identify and treat opioid adverse effects, and rotate opioids. This is particularly interesting in this time of opioid overdose epidemic. Furthermore, 72% of respondents felt they were able to provide better end-of-life care, with 68% perceiving they were better able to discuss issues related to advanced care planning. Our results also showed that 41 HMO fellows (54%) thought PC was better or much better than other mandatory hematology-oncology rotations, whereas 35 HMO fellows (46%) thought the educational experience was neither better nor worse and none thought it was worse.

A contributing factor to the favorable perception of the PC rotation may be the personalized educational curriculum fellows experience in their rotation. The faculty can identify trainees’ areas of weakness and focus their training on these areas. Before starting the clinical rotation, the fellows also go through an orientation session during which the goals of the rotation are set and they are provided educational materials regarding PC. Each fellow is assigned a mentor who is available regularly, and all fellows can provide feedback at the end of their rotation. Feedback has been used to consistently improve on the rotation and didactic structure. The HMO fellows also experience caring for patients in an acute PC unit and PC outpatient clinics, guaranteeing them myriad patient care experiences. Additional research is needed to better understand factors that affect oncology fellows’ perception of PC education.

In a recent survey of NCI-designated and non-NCI cancer centers, fewer than half offered PC fellowship programs and mandatory rotations in PC for medical oncology fellows.20 In contrast, 95% of our respondents thought the PC rotation should be mandatory and 98% would recommend it to their colleagues. The overwhelming positive perception that the PC rotation should be mandatory and is highly recommended highlights the value and need placed by our respondents on additional training in symptom management and end-of-life care. Research is needed to examine variations in PC rotations for medical oncology fellows, as well as the perceptions of these fellows regarding the PC rotation.

The PC rotation was especially beneficial for the HMO fellows in understanding the spectrum of patient and caregiver scenarios ranging from early cancer treatment and comprehensive symptom management to end-of-life care. We believe a contributing factor to the overwhelmingly positive feedback from the respondents is the consistency of the approach to care by the faculty and the interdisciplinary team. By observing a formal and standardized approach to care, the fellows can attain PC knowledge and skills consistently. Another contributing factor is the extensive didactic sessions provided by the chair and all faculty members, which are validated by the bedside teaching sessions and clinical cases the HMO fellows encounter.

Opioid management is a critical topic of interest, because the country is in midst of an opioid overdose epidemic. Although most respondents felt they were better prepared to prescribe and manage opioid treatment and the related adverse effects, a small percentage of respondents perceived they were not adequately skilled to independently manage opioid treatment. This may be a result of the complex nature of cancer pain and opioid management, and may need longer than a 4-week rotation to feel confident with opioid pain management. In contrast, Von Gunten et al25 randomly assigned HMO fellows to one of the three cohorts: digital education, digital education plus a 4-week clinical rotation to PC, and delayed digital education by 1 year as a delayed control. They reported a 73% to 75% improvement in PC domains and practice behavior change of opioid prescription after completing the fellowship. However, opioid-prescribing behavior was significantly better for the first cohort of digital education, but there was a deterioration in opioid-prescribing behavior in the digital education plus a 4-week clinical rotation to PC cohort.25 This may be the result of fellows on rotation being able to observe complex opioid regimens and needing more time to master details of opioid physiology, dose titration, metabolism, and rotations. In addition, with changing perception and regulations surrounding opioid prescription amid an epidemic, oncologists may feel less comfortable prescribing opioids despite reporting improved perception in knowledge. Moreover, clinical rotation assists in gaining experience in real-life situations, which is appreciated in a PC rotation.

Responses to certain domains, including ethical issues and coping with stress associated with end-of-life care, showed some respondents did not perceive they were fully comfortable with these issues. Similar to opioid management, 4 weeks may not be enough time to delve into these complex areas and these areas need to be a continuous part of any training program.

In our study, only 25% of the respondents deliver PC on their own. PC practiced by oncologists is variable. In a busy academic setting, oncologists prefer to refer patients to PC, and in the community setting, they may practice primary PC, according to our findings. Studies are needed to better identify factors that influence oncologists practicing primary PC.

There are limitations to this study. The study was conducted at a single, academic, NCI-designated cancer center. The study needs to be replicated at multiple institutions that meet minimal required standards for PC education. This will provide similar educational structure with minimal variations. The PC at our institution consists of a full complement of multidisciplinary specialists working in the inpatient consultation service, PC unit, and outpatient center. Other institutions with a smaller PC service or with less focus on academics and education for fellows may not be able to provide their oncology fellows the same experience. Another limitation is lack of measurements of change in clinical practice and knowledge based on standardized tests and review of electronic medical records before and after the rotation. Future research should incorporate these measures and compare them with those of a control group.In conclusion, HMO fellows reported PC rotation improved their knowledge in all PC domains, that PC rotation was better than other oncology rotations, and that the PC rotation should be mandatory. They also were more likely to refer patients to PC after the 1-month rotation. All HMO programs that offer well-established PC should start and support a mandatory PC rotation during fellowship training.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Departmental Funds

Footnotes

Presented as a poster at ASCO Palliative and Supportive Care in Oncology Symposium, San Diego, CA, November 16-17, 2018.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Suresh K. Reddy, Kimberson Tanco, Eduardo Bruera, Robert Wolff

Administrative support: Eduardo Bruera, Robert Wolff

Collection and assembly of data: Suresh K. Reddy, Kimberson Tanco, Janet L. Williams, Sriram Yennu

Manuscript writing: Suresh K. Reddy, Kimberson Tanco, Diane D. Liu, Janet L. Williams, Sriram Yennu, Robert Wolff, Eduardo Bruera

Final approval of manuscript: Suresh K. Reddy, Kimberson Tanco, Diane D. Liu, Janet L. Williams, Sriram Yennu, Robert Wolff, Eduardo Bruera

Accountable for all aspects of the work: Suresh K. Reddy, Kimberson Tanco, Diane D. Liu, Janet L. Williams, Sriram Yennu, Eduardo Bruera

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Integration of a Mandatory Palliative Care Education into Hematology-Oncology Fellowship Training in a Comprehensive Cancer Center: A Survey of Hematology Oncology Fellows

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jop/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Sriram Yennu

Research Funding: Bayer (Inst), Roche (Inst), Helsinn Therapeutics (Inst)

Robert Wolff

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties from McGraw-Hill: editor: MD Anderson Manual of Medical Oncology, 3rd edition.

Eduardo Bruera

Research Funding: Helsinn Healthcare (Inst)

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levy MH, Back A, Benedetti C, et al. : NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 7:436-4732009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abrahm JL: Integrating palliative care into comprehensive cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 10:1192-11982012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. : Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 35:96-1122017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dittrich C, Kosty M, Jezdic S, et al: ESMO/ASCO Recommendations for a global curriculum in Medical Oncology Edition 2016. ESMO Open. 1:e000097, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-7422010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. : Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302:741-7492009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383:1721-17302014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. : Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: Outcomes from the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 33:1446-14522015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elsayem A, Smith ML, Parmley L, et al. : Impact of a palliative care service on in-hospital mortality in a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 9:894-9022006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. : Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 30:454-4632011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. : Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA 299:1698-17092008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS: Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol 9:87-942011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lupu D: Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 40:899-9112010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. : The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: Will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage 55:1216-12232018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz CE, Goulet JL, Gorski V, et al. : Medical residents’ perceptions of end-of-life care training in a large urban teaching hospital. J Palliat Med 6:37-442003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meo N, Hwang U, Morrison RS: Resident perceptions of palliative care training in the emergency department. J Palliat Med 14:548-5552011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford GB, Zambrano SC: Junior doctors’ views of how their undergraduate clinical electives in palliative care influenced their current practice of medicine. Acad Med 90:338-3442015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amini A, Miura JT, Larrieux G, et al. : Palliative care training in surgical oncology and hepatobiliary fellowships: A national survey of the fellows. Ann Surg Oncol 22:1761-17672015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Hematology and Medical Oncology. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/155_hematology_oncology_2017-07-01.pdf?ver=2017-04-27-154137-833.

- 20.Hui D, Bansal S, Strasser F, et al. : Indicators of integration of oncology and palliative care programs: An international consensus. Ann Oncol 26:1953-19592015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. : Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA 303:1054-10612010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buss MK, Lessen DS, Sullivan AM, et al. : Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care: Results of a national survey. Cancer 117:4304-43112011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas RA, Curley B, Wen S, et al. : Palliative care training during fellowship: A national survey of U.S. hematology and oncology fellows. J Palliat Med 18:747-7512015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong A, Reddy A, Williams JL, et al. : ReCAP: Attitudes, beliefs, and awareness of graduate medical education trainees regarding palliative care at a comprehensive cancer center. J Oncol Pract 12:149-150, e127-e1372016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Von Gunten CF, Periyakoil V, Brown A, et al: Integration of palliative care into oncology: A curriculum development project. J Clin Oncol 35:202, 2017 (31_suppl)