Abstract

This review takes an inclusive approach to microvascular dysfunction in diabetes mellitus and cardiometabolic disease. In virtually every organ, dynamic interactions between the microvasculature and resident tissue elements normally modulate vascular and tissue function in a homeostatic fashion. This regulation is disordered by diabetes mellitus, by hypertension, by obesity, and by dyslipidemia individually (or combined in cardiometabolic disease), with dysfunction serving as an early marker of change. In particular, we suggest that the familiar retinal, renal, and neural complications of diabetes mellitus are late-stage manifestations of microvascular injury that begins years earlier and is often abetted by other cardiometabolic disease elements (eg, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia). We focus on evidence that microvascular dysfunction precedes anatomic microvascular disease in these organs as well as in heart, muscle, and brain. We suggest that early on, diabetes mellitus and/or cardiometabolic disease can each cause reversible microvascular injury with accompanying dysfunction, which in time may or may not become irreversible and anatomically identifiable disease (eg, vascular basement membrane thickening, capillary rarefaction, pericyte loss, etc.). Consequences can include the familiar vision loss, renal insufficiency, and neuropathy, but also heart failure, sarcopenia, cognitive impairment, and escalating metabolic dysfunction. Our understanding of normal microvascular function and early dysfunction is rapidly evolving, aided by innovative genetic and imaging tools. This is leading, in tissues like the retina, to testing novel preventive interventions at early, reversible stages of microvascular injury. Great hope lies in the possibility that some of these interventions may develop into effective therapies.

Keywords: diabetes mellitus, cardiometabolic disease, diabetes complications, microvessels, microvascular rarefaction, vascular endothelium

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

In each of the 6 tissues reviewed, we highlight the reciprocal relationship(s) between the tissue’s somatic cells and the microvasculature serving them. Together these components function as a microvascular unit. Early in their course, diabetes mellitus and cardiometabolic disease disrupt these microvascular units and produce tissue dysfunction. Over time, this disruption leads to common (eg, increased endothelial barrier permeability, pericyte loss, capillary rarefaction, disordered angiogenesis, etc.) as well as tissue-specific (eg, microglia activation in the central nervous system and retina, sympathetic overactivity, and perivascular adipose inflammation in peripheral tissues) microvascular injury responses that are orchestrated by a host of both systemic and local signaling processes.

ESSENTIAL POINTS.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and cardiometabolic disease (CMD) can have clinically significant adverse effects on microvascular function and precede the classical eye, kidney, and nerve DM complications by years or decades

Within tissues, the microvasculature forms part of functional microvascular units that are regulated by physical stress and autocrine, paracrine, neural, and endocrine signaling. Though tissue-specific in detailed construction, there are striking structural and functional commonalities in health and disease

Pathways that provoke microvascular dysfunction in CMD have been extensively studied, but those that prevent dysfunction or delay progression less so. With increasingly refined imaging, molecular, and genetic tools, tissue microvascular defenses will be an important focus of future investigation

Outline

The aim of this review is to provide an update on recent advances in the understanding of microvascular disease and dysfunction in diabetes mellitus (DM) and cardiometabolic disease (CMD; variably characterized hereafter by elements of insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and central adiposity). We start with a brief discussion of normal microvascular function and its regulation. We then consider the long delay between human DM diagnosis and clinical microvascular disease, noting that microvascular dysfunction occurs much earlier and follows a time course consistent with that observed for provoking oxidative stress in microvascular cells in vitro. Next we jointly discuss microvascular disease in retina, brain, and peripheral nerves, with an emphasis on the neurovascular unit (NVU) and recent progress with early detection of microvascular dysfunction in these tissues. A review of microvascular dysfunction in skeletal and cardiac muscle follows, including the role of perivascular adipose tissue (PVAT) and sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity at these sites. We then briefly summarize data indicating the pathogenetic role of early microvascular dysfunction in the kidney. Finally, we close with comments suggesting future avenues of investigation.

The microvasculature: definition, structure, and function

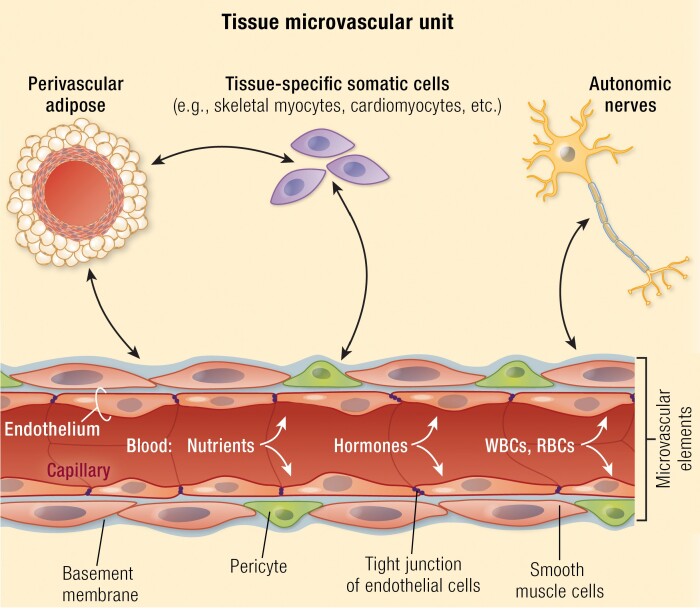

The microvasculature includes blood vessels between first-order arterioles and first-order venules. Its capillaries comprise endothelial cells (ECs), pericytes, and a basement membrane (BM), while arterioles and venules add a layer of smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and can have SNS innervation. Functionally, it is the major site of gas, nutrient, waste, protein, hormone, and drug exchange between blood and tissues. Physiologic variables that affect the exchange process for any substance include its arterial concentration, blood flow, and EC surface area and permeability. By varying EC permeability, surface area, or blood flow, a tissue can self-regulate microvascular exchange. For highly permeable substrates like oxygen or carbon dioxide, surface area and flow are the key regulated variables.

Regulation of microvascular perfusion

The microvasculature responds to an array of signals that support normal tissue function. These regulatory responses include autoregulation and local tissue, neural, and systemic regulation. Autoregulation is the ability of the vasculature to maintain flow (and hence nutrient and substrate delivery) constant over a wide range of systemic blood pressures. Among mechanisms responsible for autoregulation, arteriolar wall stretch (ie, the myogenic response) appears to be central and is perhaps augmented by local pO2 sensing and vasodilator release. Environmental and physical changes within tissues also regulate microvascular function. For example, muscle contraction increases both blood flow and capillary surface area to enhance exchange of oxygen and nutrients with myocytes (1, 2). Tissue stretch, along with release of nitric oxide (NO), neurotransmitters, and eicosanoids, contribute to this response. The SNS is also able to regulate arteriolar tone and consequently microvascular blood flow (3).

Within many (perhaps all) tissues, the microvasculature exists in a reciprocal, paracrine, regulatory relationship with perivascular tissues to form a microvascular unit (see graphical abstract). Examples include the central nervous system (CNS) and retinal NVUs, whereby constant communication between ECs, pericytes, astrocytes, and neurons smoothly regulates blood flow to areas of increased neural activity (4, 5). In CNS, this process underlies functional BOLD magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Another example is perivascular fat contributing to the regulation of both large artery and microvascular flow in a number of tissues (6, 7). Finally, the microvasculature responds to systemic signals including endocrine, nutritional, and neural stimuli. Examples include angiotensin (8, 9), thyroid hormone (10), insulin (11-13), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) (14), and meal ingestion (15), among others.

Timeline for developing microvascular complications in human DM

Due to the severe adverse effects of untreated retinal microvascular disease and the accessibility of human retinal microvasculature to detailed anatomic and physiologic study, the impact of DM ± CMD on microvascular injury in humans has been most extensively studied in the retina. In the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) primary prevention cohort virtually no retinopathy developed in the first 3 years, and at 8 years (~11 years of type 1 DM) only 50% of the conventionally treated group (whose glycated hemoglobin averaged ~ 9%) had detectable retinopathy (16). The time courses for renal and peripheral nerve complications were comparable, but prevalence was lower (16). The DCCT and later United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study results (17) underscore the gradual evolution of microvascular disease and the importance of good glycemic control for preventing microvascular complications. Interestingly, microvascular complications arise earlier and with higher frequency in the course of type 2 DM. This has been most clearly seen in comparative studies of children developing either type 1 or type 2 DM (18, 19). Eppens et al. found that adolescents with short duration type 2 DM (median of 1.3 years) had a significantly greater prevalence of microalbuminuria than adolescents with longer duration type 1 DM (median of 6.8 years), despite comparable or better glycemic control in the type 2 DM subjects. Those with type 2 DM, however, had greater prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia (18). Cross-sectional studies of adult populations also demonstrate that hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity associate with increased prevalence of retinopathy in persons without DM (20). In aggregate, these data emphasize that components of CMD increase risk for development of microvascular complications in DM.

These and other findings provoked intense investigation of basic mechanisms whereby hyperglycemia caused such adverse microvascular consequences. We refer the reader to several excellent reviews of the pertinent pathways involved (21-23). The current consensus holds that excess production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by mitochondria and cytosolic oxidases (eg, NADPH oxidases) in vascular ECs initiates the early stages of microvascular injury. Excess supply of either glucose or fatty acids can drive this early change. Brownlee’s group has proposed a compelling unified hypothesis whereby ECs respond to hyperglycemia by generating excess ROS, which over several days leads to breaks in DNA that activate the DNA repair enzyme poly[ADP ribose]polymerase 1. This enzyme can poly-ADP-ribosylate and inhibit cytosolic glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, thereby slowing glycolytic flux and increasing the concentration of glycolytic intermediates. These effects subsequently enhance flux of hexoses through the sorbitol and glutamine–fructose amido-transferase pathways, increase diacylglycerol by raising triose phosphate concentrations, activate several PKC-isoforms (β, δ, and θ), and supply substrates for synthesis of methylglyoxal (a highly active agent for non-enzymatic glycation). The increased methylglyoxal concentrations and PKC activities promote activation of the nuclear factor kappa B innate inflammatory pathway, which drives the injury process forward (22).

In the in vivo microvascular environment, these injury processes affect ECs (which may be particularly susceptible), pericytes, SMCs, fibroblasts, and vascular progenitor cells. The same processes may affect the somatic cell hosting a specific microvascular bed. The microvasculature can counter the evolving ROS injury by enhancing production of superoxide dismutase, catalase, and dehydrogenases (which activate repair processes) and recruiting circulating progenitor cells to replace irreversibly damaged cells. Increased nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor-2 (NRF-2) transcription is but one restorative response to counter excess ROS in vascular cells. Hyperglycemia in both cultured and in vivo ECs increases NRF-2, and NRF-2 knockout mice show diminished protection from hyperglycemia-induced ROS injury (24). This suggests that a dynamic balance between ROS and antioxidant defense pathways regulates the extent of microvascular ROS injury. It is important to consider that while high glucose concentrations induce major ROS stress in cultured ECs within hours/days (25, 26), and that hyperglycemia causes microvascular injury in animals within weeks/months (22, 26), it is uncertain why hyperglycemia in humans requires a decade or more to provoke anatomic microvascular disease. Clearly, many biologic processes that might accelerate or interdict the development of classical microvascular DM complications remain shrouded.

We suggest that in many tissues microvascular dysfunction anticipates classic microvascular disease by years or decades, and that dysfunction has a time course consistent with the ROS-induced EC stress seen with excess glucose or lipids in vitro. This advances the question of whether identifying early microvascular dysfunction would allow testing of interventions that could reverse dysfunction and slow or prevent its progression to microvascular disease. The potential benefits of such intervention are considerable given that DM ± CMD microvascular dysfunction affects not only the retina, kidney, and peripheral nerves, but also cardiac and skeletal muscle, brain, and many other tissues.

The retinal, brain, and peripheral nerve microvasculature

The microvasculature of these tissues share anatomic and functional features that prompt unified discussion. The microvasculature of each is lined by a continuous endothelium with tight junctions between cells which, together with pericytes and BM, form the blood–retina barrier (BRB), blood–brain barrier (BBB), and blood–nerve barrier (BNB), respectively. Each subserves neural tissues with high metabolic demands for glucose and oxygen and each requires a strongly protected extracellular fluid environment. Much of the energy requirement of these tissues (~50%) is consumed by the Na+-K+-ATPase to support neuron repolarization. Each of these tissues lacks significant energy stores and requires a continuous supply of oxygen and glucose for oxidative metabolism, underscoring the need for a functionally intact microvasculature. Oxygen crosses the tight endothelium by simple diffusion, while glucose movement is facilitated by GLUT-1 transport proteins on both the luminal and antiluminal membrane of the capillary EC. It is self-evident that an anatomically disordered microvasculature, with pericyte loss, capillary rarefaction, and breakdown of endothelial barrier function, would impair nerve function. Moreover, over the last 2 decades it is increasingly evident that the microvascular function of these tissues coordinates with the host tissue to form a NVU. This has become a focus of special interest in both brain and retina.

Retinal microvasculature

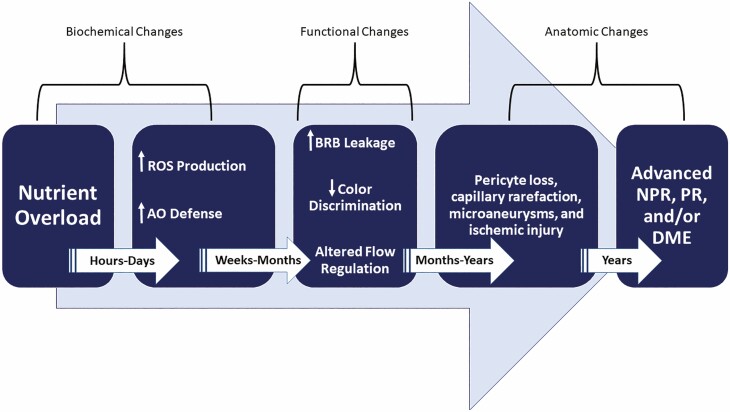

Our understanding of the development, progression, and clinical impact of treatment of DM retinopathy (DR) far exceeds that of microvascular disease in other tissues. Direct microvasculature visualization by fluorescein angiography and fundus photography, together with visual acuity measures, allows objective grading of DR onset, progression and treatment effectiveness. Thus, the preventive benefits of glycemic (16, 17) and hypertensive control (27), and the therapeutic benefits of photocoagulation (28, 29), anti-VEGF (29-31), and vitrectomy (32) therapies, have been validated. We know that microvascular lesions of early DR (eg, pericyte loss, micro-aneurysms and capillary dropout) arise after years of clinically silent injury (33) (Fig. 1). New methodologies for probing retinal structure, including optical coherence tomography (OCT), OCT angiography (34), spectral OCT (35), and adaptive optics laser scanning microvascular imaging (36, 37), allow structural investigation of both superficial and deep layers of the retinal microvasculature and its relationship to neural elements. These structural methods, coupled with measures of neurovascular function, including multifocal electroretinography, microperimetry, and flicker light stimulation, have focused attention on the retinal NVU as a site of early retinal dysfunction presaging DR development. The aggregate components of the retinal NVU include the EC, pericytes, astrocytes, Mueller cells (a specialized astrocyte), microglia, and neurons. The Mueller cells and other astrocytes function as a signaling node between the neuron and vascular cells (38). Integrated function of the retinal NVU is required for normal retinal function, as selective lesioning of one component of this unit typically leads to dysfunction of other elements (39). Importantly, it is now clear that probing the functional behavior of the retinal NVU can identify dysfunction early in the course of DM and may provide a method for true early detection. For example, Lott et al. reported that the vasoconstrictor response to hyperoxia and the vasodilator response to flicker light is abnormal in subjects with well-controlled type 2 DM without observable anatomic microvascular retinopathy (40). Biochemical and electrophysiologic studies have confirmed that astrocytes and Mueller cells regulate vascular tone in the retina and become dysfunctional early in the course of DM, preceding anatomic changes (41). In another study comparing healthy controls to persons with type 1 DM but without visible DR, both the vasodilatory response and blood flow velocity increase were less in persons with DM than controls while the electroretinograms were comparable, suggesting that dysfunction of neurovascular coupling was responsible and preceded anatomic DR (42). Earlier detection of clinically silent dysfunction may both identify individuals at highest risk for developing anatomic DR and facilitate testing new therapeutics early in its course. We do not yet know the reversibility of such dysfunction, its relationship to glycemia or other CMD factors that influence retinopathy progression, or indeed whether it predicts progression at all. It does, however, afford the opportunity to test the functional impact of clinical variables including hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, insulin, and other hypoglycemic agents. It may also allow testing the interaction of DM with hypertension, lipid disorders, and genotype. We anticipate that in coming years this preclinical stage of retinopathy, which likely extends for years, will be an area of intense investigation.

Figure 1.

An approximate time course for the development of microvascular lesions within the retina neurovascular unit. Early biochemical effects from hyperglycemia (or deficient insulin action) are marked by increased production of ROS (eg, superoxide, peroxynitrate, hydrogen peroxide, etc.). Less well defined, but apparent in other tissues, is activation of antioxidant defense mechanisms. With time, functional changes in the neurovascular unit of the retina occur with increased permeability of capillaries as well as changes in the neural retina that affect contrast and color discrimination and alter blood flow regulation. These typically antedate early anatomic changes that include pericyte loss, capillary dropout, micro-aneurysms, venous beading, and intraretinal microvascular abnormalities. With longer duration of hyperglycemia, more advanced forms of retinopathy (eg, NPR and PR) as well as DME develop. ROS, reactive oxygen species; AO, antioxidant; BRB, blood–retinal barrier; NPR, nonproliferative retinopathy; PR, proliferative retinopathy; DME, diabetic macular edema.

While the DCCT and other studies demonstrated the impact of glycemic control in preventing onset and progression of retinopathy, glucose alone does not fully explain an individual’s DR risk (43). In the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, >10% of non-DM subjects were found to have anatomic lesions on fundus photography consistent with early DR (20). Hypertension and smoking were also recognized as significant associated factors in this study, and some data suggests that dyslipidemia similarly contributes (44). These data highlight the importance of recognizing multiple, modifiable CMD microvascular risk factors in preventing progressive retinal microvascular disease, as is current best practice for macrovascular disease prevention.

Retinal structural studies using new technologies are early, but they afford promise of being able to separately and quantitatively assess contributions of vascular rarefaction and ischemia, vascular leak with edema, and separate neurovascular injury (45). Even in subjects without recognizable retinopathy, microvascular density mapping using OCT angiography demonstrated diminished vascular density in DM versus control subjects (46). This is also seen in non-DM hypertensive subjects (47). These improved functional and structural technologies, combined with opportunities for testing new therapies (48), will likely provide new insights into processes that drive the transition from microvascular dysfunction to disease. Many important questions remain, including whether there are specific cells within the retinal NVUs that drive the development of dysfunction or its progression to anatomic disease. There are data from extensive clinical observations to suggest that factors like hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia each increase risk for development or progression of both retinopathy and nephropathy in persons with DM (49, 50)

Brain microvasculature

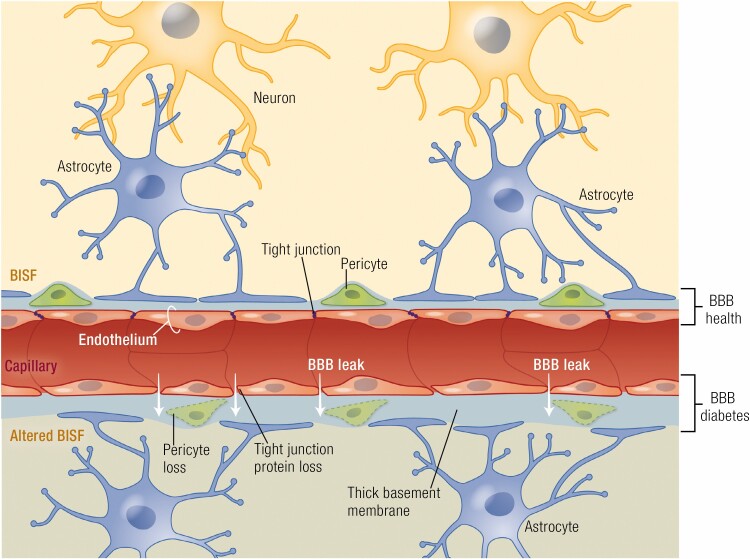

Like retina, brain microvasculature functions within a NVU composed of ECs, pericytes, SMCs, astrocytes, neurons, and a BM (51, 52) (Fig. 2). Brain ECs, with well-developed tight junctions, form a high resistance barrier to solute entry and express specific transporters for glucose (53), amino acids, and other needed hydrophilic nutrients as well as extrusion pumps that exclude both noxious solutes and some therapeutics. Larger molecules (eg, albumin) cross the brain ECs slowly, mediated by vesicular transport processes that involve caveolae or clathrin-coated vesicles (54). Pericytes cover ~30% of the brain capillary EC surface and are enveloped within the BM, playing key roles in maintaining EC function (4, 55) and regulating perfusion (56, 57). Astrocyte foot processes form a near-continuous cover of the BM at the capillary level and participate in excluding large macromolecules from the brain interstitial fluid (58, 59). Neurons communicate with astrocytes that produce NO, eicosanoids, and other vasoactive compounds that regulate microvascular SMC contraction or relaxation. In addition to regulating nutrient and oxygen delivery by altering perfusion, elements within the NVU can regulate selective transport of peptides (eg, IGF-1, insulin, leptin) across the EC barrier (60, 61). In preclinical studies, DM elicits anatomic changes within the brain NVU similar to those seen in the retina, including BM thickening, pericyte loss, and EC apoptosis (56, 62, 63). In mice, high-fat diet accelerates aging-related capillary rarefaction (64). In humans, capillary rarefaction appears to increase with age and is worsened by insulin resistance (65).

Figure 2.

The brain NVU (schematized here at the capillary level) includes neurons which reciprocally signal via astrocytes to the microvasculature of small arterioles and capillaries. This signaling affects tone of SMCs and pericytes and regulates EC permeability properties. The astrocyte foot processes also limit passage of macromolecules to BISF. In health, the low permeability of the blood-brain barrier depends critically on the tight junctions of ECs but also requires normal function of pericytes, astrocytes, and the basement membrane. With long-standing DM (lower portion of figure) there is increased BBB permeability due to loss of tight junction proteins. Pericytes, which cover much of the capillary vasculature, are lost facilitating the permeability increases. Over time, ECs are also lost and capillary rarefaction occurs, thus altering the composition of BISF. NVU, neurovascular unit; BBB, blood–brain barrier; DM, diabetes mellitus; SMC, smooth muscle cells; EC, endothelial cell; BISF, brain interstitial fluid.

Our understanding of brain NVU function/dysfunction in health and DM ± CMD is less developed than for retinal NVUs, largely due to the spatial/functional heterogeneity of brain and lack of high-resolution methods to directly examine brain microvasculature in vivo. Despite this, interest in the relationship of cerebral microvascular dysfunction has intensified with the recognition of an increased prevalence of impaired cognitive function and dementia among persons with DM (66, 67) or CMD (68-71). Interestingly, BM thickening is present in the brain microvasculature of persons with DM (72) and in non-DM Alzheimer’s patients (73). Brain total grey matter and hippocampal volumes are reduced in persons with both DM and Alzheimer’s compared with controls (74), but the importance of these anatomic findings to cognitive changes is uncertain. Supporting the systemic nature of DM microvascular disease, retinal microvascular disease (as seen with human DM or hypertension) predicts both the development and progression of brain anatomic microvascular injury on MRI (75).

A key question is whether DM ± CMD drives early functional changes in the brain’s NVUs and affects risk for long-term cognitive decline. One function of the NVU is to regulate regional blood flow in response to the needs of local neurons. This local regulation can be detected by functional MRI and appears to operate, at least in part, by the astrocyte serving as a signaling node between the neuron, pericytes, SMCs, and ECs (58, 76, 77). The relative inaccessibility of the human brain to imaging with microvascular resolution, as well as to other methods for probing physiologic microvascular regulation, hampers testing for early functional microvascular changes attributable to DM or CMD. Despite this, there is accumulating evidence from both preclinical (54, 78, 79) and human (72, 74) studies that the cerebral microvasculature is adversely affected by DM and other insulin resistance syndromes (80) well before the appearance of micro-infarcts or vascular dementia.

Given that obesity (69-71, 81), CMD (68, 81), and DM (66, 67) each increase risk for early cognitive dysfunction, whether it is insulin resistance per se that increases risk and whether the microvasculature is involved requires attention. While not a major regulator of brain glucose metabolism, insulin does affect many CNS cell types and processes which might be adversely affected by insulin resistance. These include ion channel synthesis and localization in neurons, cytokine release by astrocytes and microglia, and (pertinent to the microvasculature) NO production by ECs and relaxation of arterioles (80). In a study of middle-aged volunteers with normal cognition, both macrovascular blood flow and microvascular perfusion were decreased in participants with greater insulin resistance as measured by HOMA-IR (82). Preclinical studies also demonstrate that high-fat diet–induced insulin resistance can decrease the transport of insulin across the BBB ECs (60). Relevant to this, a recent study reported that insulin infusion in healthy older adults expanded the volume of BOLD image excitation induced by sustained cognitive demand (83). In these healthy individuals, there was a significant, positive correlation between the BOLD image volume excitation, metabolic insulin sensitivity, and cognitive performance. This suggests that in the CNS (as in multiple peripheral tissues), microvascular perfusion may be directly regulated by plasma insulin concentration in insulin-sensitive individuals. Alternatively, it may indicate a direct insulin effect on the brain with secondary increases in microvascular perfusion, perhaps through actions on astrocytes that regulate local blood flow. Insulin’s ability to enhance brain microvascular perfusion in insulin-sensitive subjects may provide an important clue to the causal relationship between insulin resistance and the increased prevalence of cognitive impairment seen with these disorders. The increased availability of powerful MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) neuroimaging methods promises to yield new insights into the pathogenesis of human cognitive dysfunction in insulin-resistant states.

Peripheral nerve microvasculature

Distal sensory polyneuropathy (DSPN) is the most common form of DM neuropathy and is closely associated with microvascular dysfunction. Recent reviews (84-88) have covered the spectrum of diagnosis and management of DM neuropathies. Here we focus on the microvasculature’s contribution to DSPN pathogenesis and discuss several mechanistic therapies.

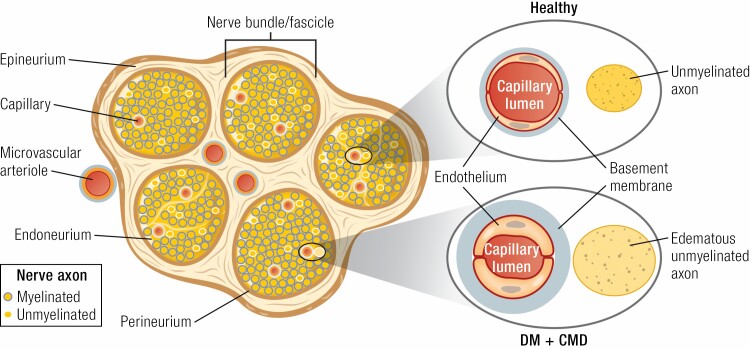

The pathophysiology of DSPN is complex and multifactorial, with hyperglycemia, oxidative and nitrosative stress, microvascular inflammation, autoimmune-mediated nerve destruction, insulin resistance, and genetic susceptibility contributing (23, 89, 90). These factors advance metabolic and microvascular alterations that directly affect Schwann cells and nerves (85, 90-92). Healthy nerves are perfused by the vasa nervorum (90), which is crucial for preservation of appropriate nerve structure and function (93). Indeed, vasa nervorum dysfunction contributes to nerve ischemic injury (94) during the development of DSPN. The most common structural abnormality in DM vasa nervora is thickening of endoneurial BM (95-97), which in turn predicts neuropathic severity (90, 98, 99). For example, sural nerve biopsies from persons with DSPN demonstrate endoneurial BM thickening along with EC proliferation and hypertrophy, findings which are generally absent in DM patients without DSPN (85, 95). Hyperglycemia blunts vasodilation and promotes capillary BM thickening and EC hyperplasia, which diminishes oxygen tension (85, 90, 100) in the small endoneurial vessels (90, 101), leading to endoneurial hypoxia and neuronal damage (85, 102, 103) (Fig. 3). Conduction velocities in these same nerve trunks are also reduced in proportion to the reduction in their oxygen tension (90, 101). Moreover, studies of rats with DM have demonstrated that reduction of nerve conduction velocity is preceded by impaired vasodilation in epineurial arterioles (104). These functional microvascular changes occur relatively early in the course of DM, as reductions in microvascular hyperemia have been observed prior to the onset of hyperglycemia in individuals at risk for type 2 DM (105). Recent work has also demonstrated that DM and components of CMD may have differential effects on small versus large nerve fibers. The Utah Diabetic Neuropathy Study examined 218 type 2 DM subjects without neuropathy symptoms, or with symptoms of <5 years, in order to evaluate risk factors for DSPN development. Results showed that obesity and hypertriglyceridemia related to loss of small unmyelinated axons, whereas hyperglycemia related to large myelinated fiber (ie, motor conduction velocity) loss (106).

Figure 3.

Unmyelinated and myelinated peripheral nerve bundles are ensconced in the outer layer of connective tissue (epineurium) and an inner band (perineurium) that delineates the nerve fascicles. Microvascular arterioles penetrate both layers bringing a capillary supply to the endoneurium (a peripheral nerve analog of cerebrospinal fluid). In health, the capillary endothelium maintains a tight barrier regulating glucose, oxygen, and electrolyte access to axonal elements in the endoneurium. With DM and CMD, the capillary basement membrane expands and there is endothelial hypertrophy and increased permeability resulting in diminished flow and oxygen delivery, axon edema, and subsequent nerve dysfunction. Injury induced by hyperglycemia is exacerbated by other CMD factors (eg, hypertension, obesity, dyslipidemia, etc.). Chronic capillary rarefaction produces worsened ischemia and axon degeneration. DM, diabetes mellitus; CMD, cardiometabolic disease.

Current evidence suggests that breakdown of the BNB plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of DSPN. The BNB consists of the endoneurial microvessels within the nerve fascicle and the investing perineurium, providing a selective blood–tissue interface within the peripheral nerve endoneurium (107). The BNB, like the BBB and BRB, is formed by a continuous endothelium containing tight junctions that severely restrict paracellular movement of solutes and proteins (108). One key difference of the BNB, however, is its lack of an astrocyte sheath. Instead, for myelinated axons a circumferentially layered Schwann cell membrane separates nerves from microvessels (except at nodes of Ranvier). This arrangement allows enhanced nutrient and oxygen delivery to sites that require increased energy for saltatory nerve conduction. Furthermore, EC gap junction connexins allow direct communication and transfer of ions and small signaling molecules between ECs (109, 110). In this manner, the vascular cells constituting the endoneurial BNB are coupled into networks, are excitable but do not express action potentials, and can provide coordinated response to tissue needs (109). In order to reach the endoneurial extracellular space, blood-borne molecules need to cross the endoneurial vascular endothelium or the perineurium that surrounds the nerve fascicle (107). The restricted permeability of the BNB and the enveloping Schwann cells protect the endoneurial extracellular fluid microenvironment from drastic concentration changes in electrolytes or solutes (111); however, local or systemic increases of BNB permeability can lead to neuronal dysfunction and DSPN development (107). Early reports linked DSPN to increased BNB permeability to mannitol in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced DM rats (112). Subsequently, increased endoneurial concentrations of large molecules like albumin, immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M were observed in DM patients with and without neuropathy (113), suggesting that increased BNB permeability may precede and contribute to the development of DSPN (110, 113). Recent work seemingly affirmed this hypothesis by showing that protein accumulation within the endoneurium disrupts osmotic balance and causes nerve edema (108). Other metabolic hallmarks of DM ± CMD, like hyperglycemia and increased free fatty acid flux, may also damage the BNB due to increased exposure of endoneurial EC to toxic circulating factors (110).

DSPN treatments that target the microvasculature provide further insight into the relationship between microvascular and nerve function. Hyperglycemia hastens advanced glycation end product (AGE) generation, which induces intra- and extracellular protein cross-linking and protein aggregation. AGE receptor activation alters intracellular signaling and gene expression, releases proinflammatory molecules, and results in an increased production of ROS that contributes to DM microvascular complications (23). Optimization of glycemic control, when implemented early, can delay or prevent DSPN onset and the progression of surrogate electrophysiologic markers of neuropathy in type 1 DM (114-118). Evidence for benefit is not as strong in type 2 DM, as near-normal glycemic control only modestly slows DSPN progression without reversing neuronal loss (114, 118, 119). Benfotiamine, a fat-soluble analogue of thiamine/vitamin B1, is a transketolase activator that reduces tissue AGEs and has been shown in animal models to inhibit three different pathways involved in hyperglycemia-induced microvascular damage (23, 120, 121). A 3-week placebo-controlled study identified subjective improvements in neuropathy scores and reductions in pain levels in human subjects that received 200 mg daily of benfotiamine (122). In a 12-week study, the use of benfotiamine plus vitamin B6/B12 significantly improved peroneal nerve conduction velocity and vibratory perception (23, 123). However, there are no long-term trial data showing benefit of benfotiamine in treatment of DSPN.

Defective antioxidant mechanisms that increase free-radical production and generate ROS also contribute to the development of DSPN (120, 124). Alpha lipoic acid (ALA) is an antioxidant with thiol-replenishing, redox-modulating properties that is currently approved to treat DSPN in Germany (23, 120). Multiple studies demonstrate ALA’s beneficial effects on microcirculation (125) and neuropathic symptoms (126, 127). Ziegler et al. (128) performed a meta-analysis of four short-term (ie, weeks) randomized controlled trials involving >1200 DSPN patients and found that 600 mg daily of intravenous ALA significantly reduced neuropathic symptoms and improved neuropathic deficits (23). Conversely, a multicenter randomized double-blind parallel-group trial reported no improvement in neurophysiologic function, quantitative sensory testing, or a composite neuropathy score after 4 years of treatment with either oral ALA or placebo (129). Given these equivocal clinical results, further testing is needed to clarify ALA’s effectiveness (23).

Endothelial dysfunction occurs early in the microvascular pathophysiology of DM ± CMD and is an established predictor of DSPN (130). Metanx, a medicinal food product containing l-methyl-folate, pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and methylcobalamin, has beneficial effects on endothelial function (131). In a 24-week multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Metanx significantly improved both neuropathic symptoms and quality of life (132). Another study of 544 type 2 DM patients with DSPN reported significant improvements in total symptom score (NTSS-6), quality of life, and medication satisfaction (133). Thus, Metanx may be a safe approach for short-term alleviation of DSPN symptoms. Additional studies are needed to further define these effects and their impact on long-term outcomes (23).

Despite these efforts to advance treatment, currently there are no clinically validated, disease-modifying therapies approved for DSPN (90). Thus, DSPN provides opportunities for investigation of novel agents that target microvascular function. Current experimental approaches examine the therapeutic benefits of gene therapy (with vascular endothelial growth factors) and mesenchymal therapy (with stem or progenitor cells). While there have been encouraging results from preclinical gene therapy studies (23, 93, 134, 135), results from initial human studies have been modest (136) and further investigation is necessary. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are particularly viewed as a promising regenerative therapy for DSPN due to their multipotency and paracrine secretion of both angiogenic and neurotrophic factors (137). Studies of STZ-induced DM rodents using bone marrow-derived MSC have reported improvement of DSPN (as evidenced by increased nerve conduction velocity (138), restored ultrastructure of myelinated nerve fibers, and upregulated gene expression of multiple factors participating in angiogenesis, neural function, and myelination (139)). These and other experimental results (140) suggest promise for MSC therapy for DSPN. However, the biology of MSCs in DM is quite complex. Prior work has shown that MSCs demonstrate significant functional deficits in the setting of DM (141), which may be attributable to selective and irreversible depletion of MSC subsets in persons with DM. This could potentially limit their utility as a therapeutic approach.

Skeletal muscle microvasculature

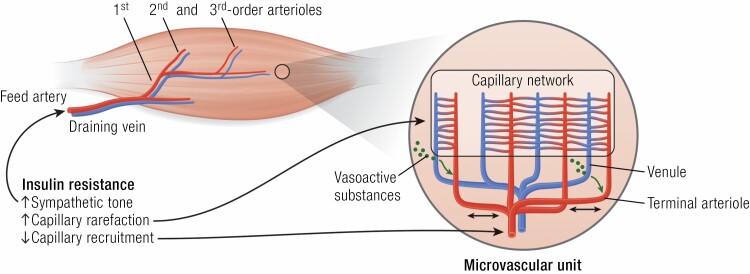

Over 50 years ago, the observation that the microvascular BM in skeletal muscle was thicker in persons with DM than healthy controls (142, 143) provided initial evidence of the ubiquitous nature of DM microvascular disease. Subsequent studies found that BM thickness was more marked with age, DM duration, and poor metabolic control (144). As there was no clear relationship between BM thickness and the increased muscle capillary permeability reported in DM (145), or to muscle contractile performance or concomitant renal microvascular disease (including microalbuminuria or mesangial thickness (146)), its significance was uncertain. Later electron and light microscopy findings indicated both accelerated muscle microvascular pericyte turnover (147) and rarefaction of microvasculature in DM (148), changes similar to those seen in DM retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. Muscle vessel rarefaction was also seen in hypertensive rodents (149) and obese non-DM subjects (150), suggesting it as a marker of CMD. Lillioja et al. observed that capillary rarefaction correlated with worsening insulin sensitivity and suggested that capillary loss could, by reduction of capillary exchange surface area, impair muscle glucose utilization (150). Consistent with this, skeletal myocyte selective knockout of VEGF-A decreased muscle capillary density and impaired insulin-mediated muscle glucose uptake in vivo while insulin action on myocytes in vitro was unaffected in this preclinical model (151). These data suggest that the structural abundance of muscle microvasculature is a functional determinant of muscle metabolic function and insulin sensitivity. Furthermore, early preclinical anatomic studies showed that in resting muscle only approximately one-third of capillaries were perfused at a given time (2). Muscle contraction increased perfusion to additional vessels within seconds, supporting the increased oxygen and nutrient needs of the working muscle. This stimulation did not involve single capillary vessels, but rather synchronous opening and closing of multiple microvascular units (each consisting of a terminal arteriole feeding ~18-24 capillaries) in response to various stimuli (152) (Fig. 4). Importantly, localized stimulation of terminal arterioles produced ascending vasodilation of second- and third-order arterioles and enhanced overall flow to nearby microvascular units. Thus, myocytes requiring increased oxygen to perform mechanical work can signal directly to adjacent vessels and these signals will ascend, principally through EC gap junctions, to feed arterioles that dilate to enhance oxygen and nutrient delivery (153-155). We now know that microvascular ECs signal via connexins to adjacent ECs and in arterioles to SMCs via gap and myoendothelial junctions to effect spreading waves of relaxation or constriction. Signals transmitted longitudinally along vessels in both ascending and descending directions modulate flow to muscle microvascular units (154, 155). In this manner, the myocyte can locally regulate blood flow to meet its energy needs in a graded, region-specific fashion, just as the neuron or retina signals its local metabolic needs by activating the astrocyte or Mueller cell, respectively.

Figure 4.

In health, inflowing blood through the feed artery is progressively distributed to smaller and smaller arterioles within the muscle microvasculature, ending in a capillary network fed by terminal arterioles paired with draining venules. To facilitate blood flow distribution that matches their oxygen and nutrient needs, myocytes release vasoactive substances into the draining venules (green arrows) with signaling transmitted to adjacent segments of terminal arterioles. The latter can signal both proximally and distally (black 2-headed arrows) via gap junctions abundant in the vascular endothelium, thereby increasing the volume of vasculature dilated (or constricted) in response to the myocytes’ needs. Overall flow is regulated by myogenic autoregulation, by sympathetic alpha-adrenergic tone, by signals from the myocytes themselves, and by circulating hormones (eg, insulin). Obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, and DM can chronically decrease muscle perfusion by actions at the feed artery and at first and second arterioles (in part through increased sympathetic tone). More distally, these CMD disorders also impair the ability of insulin to perfuse capillary beds, depriving them of nutrients and oxygen. DM, diabetes mellitus; CMD, cardiometabolic disease.

At the time this information on the coordinated regulation of flow through microvascular networks was emerging, controversy arose as to whether insulin itself had acute effects on muscle perfusion (156) and, if so, was it diminished with DM, CMD, or other conditions associated with insulin resistance? Several studies demonstrated that insulin, like muscle contraction, could increase the perfused capillary network in skin (157, 158). Applying several methods to measure perfusion, we found that insulin (infused during a euglycemic clamp) enhanced the EC surface area perfused in skeletal muscle even in the absence of increased total limb blood flow (159). Importantly, use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound methods allowed noninvasive study of conscious humans at physiologically relevant insulin concentrations (11, 12, 160-163). Recent studies from several laboratories confirm that insulin, exercise (15, 164, 165), meal ingestion (15), physical training (166), GLP-1 (14, 167), and adiponectin (168) each acutely enhance human skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion. Notably, insulin-enhanced microvascular perfusion is adversely affected by chronic insulin resistance as occurs in DM (160), CMD (12), and obesity (161), as well as acute insulin resistance that occurs either with experimental elevations of plasma free fatty acids induced by lipid infusion (169) or by infusion of proinflammatory cytokines (170). Diminished muscle microvascular insulin action is seen in both types 1 and 2 DM and occurs in the absence of hyperglycemia, indicating that it may arise from different pathogenetic changes than those attributed to hyperglycemic stress on microvascular endothelium (21, 26).

Insulin’s action to enhance skeletal muscle microvascular perfusion depends on generation of NO by the microvascular EC. Insulin activates the PI3K-Akt kinase pathway in the EC, leading to specific serine phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (171). Blocking that activation inhibits both microvascular perfusion (172) and muscle glucose metabolism (172-174). Insulin can also increase the synthesis and secretion of endothelin-1 by the EC (175). If the balance between endothelin-1 and NO production favors endothelin-1, insulin can induce vasoconstriction (176). Just as blocking NO availability prevents insulin-induced vasodilation, blocking endothelin-1 receptor A prevents insulin-induced vasoconstriction (177-179). Thus, insulin can have either a constricting or dilating effect on muscle microvasculature depending on the vascular insulin sensitivity of the elements under study. GLP-1 (180) and adiponectin (168), each acting through separate signaling pathways, also increase endothelial NO production and promote vasodilation. Interestingly, each appear to retain their vasodilatory effects in both insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive animals.

The important contribution of SNS tone to muscle microvascular perfusion has also been known for decades. In humans, reflex SNS activation (elicited by inflating bilateral thigh cuffs to decrease leg venous return) triggers a significant reflex decline of forearm blood flow and subsequently decreases insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by forearm muscle (181). Increased systemic SNS activity during exercise shunts blood from visceral tissues and noncontracting muscle, while functional sympatholysis within the exercising muscle permits needed oxygen and nutrient delivery to the working muscle (182). The impact of DM and CMD on SNS regulation of muscle microvascular perfusion has not been well studied and is a potential avenue for future investigation.

Recent studies have suggested several possible molecular pathways by which skeletal myocytes exert pathological paracrine regulation of the microvascular endothelium that contribute to vascular and metabolic insulin resistance. Hagberg and colleagues recently showed that blocking muscle expression or action of VEGF-B decreased the endothelial expression of fatty acid transport proteins and decreased muscle and EC fat accumulation, ultimately reducing muscle insulin resistance (183). VEGF-B expression is in part regulated by PGC-1α and might normally facilitate muscle fat uptake as a fuel to support mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Other recent work has suggested that valine metabolite 3-hydroxyisobutyrate can signal from muscle to ECs to increase EC fat transport, myocyte fat accumulation, and muscle insulin resistance (184). These findings suggest that targeting EC lipid transport may be a useful approach for preventing vascular and metabolic insulin resistance.

As contrast-enhanced ultrasound allows independent measurement of microvascular volume and flow velocity changes, it can provide insight on the sensitivity of these variables to graded increases of muscle contraction. In preclinical studies, even low frequency twitch can triple the volume of perfused leg muscle vasculature without affecting flow velocity (165). Similarly, light exercise by humans expands perfused microvascular volume in the exercised muscle several fold, with little or no change in flow velocity (15). These findings suggest a hierarchical regulation of microvascular perfusion, whereby expanding the microvascular volume affords increased exchange surface area and enhances tissue perfusion (ie, Fick principle) without requiring increased cardiovascular work. The microvascular dilatory effect of muscle contraction, unlike that of hormonal stimuli, is affected minimally if at all by NO inhibition (165). Release of prostacyclins, shifts of potassium or hydrogen ion concentrations, or other vasodilator mechanisms appear operative. Likewise, while insulin resistance strongly inhibits insulin’s NO-dependent microvascular action, it does not block (185) or minimally affects (164) exercise-induced increases of microvascular perfusion.

Given that exercise training stimulates muscle blood flow acutely (ie, with each bout) and muscle angiogenesis within a few weeks, its impact on microvascular capillary density has been extensively examined. Recent work shows that long duration, low-intensity exercise training may be particularly effective in stimulating capillary angiogenesis and increasing muscle capillary density (186). Given that capillary rarefaction correlates strongly with metabolic insulin resistance in humans (187), and that the acute microvascular perfusion induced by exercise persists in insulin-resistant muscle (185), there is a clear rationale for using exercise to treat muscle insulin resistance and improve muscle microvascular perfusion. In preclinical studies, 2 weeks of exercise training significantly improved both the metabolic and microvascular response to insulin during a euglycemic clamp (188). More recently, 6 weeks of resistance exercise training in humans with type 2 DM was shown to improve both microvascular perfusion and glucose tolerance following an oral glucose load (166).

Microvascular responses to insulin have been studied more extensively in skeletal muscle than in any other tissue. The important contribution of muscle to whole body glucose response to insulin provides an opportunity to test the linkage between microvascular and metabolic responses to insulin. The data reviewed provide strong evidence for an important link between insulin’s metabolic and microvascular actions in skeletal muscle in both health and DM ± CMD. Indeed, muscle microvasculature, through altered capillary recruitment, rarefaction and dysfunctional fatty acid transport, may be a major contributor to systemic insulin resistance in CMD.

Myocardial Microvasculature

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an established DM comorbidity; however, traditional risk factors do not fully explain this excess risk (189). Myocardial microvascular dysfunction (MMD) is an early feature of DM (even in patients without obstructive CVD (190)) and is now recognized as a potential contributor to CVD risk in this population (191-195). Here we discuss findings related to MMD in general and highlight studies relevant to DM, CMD, and insulin-resistant states, recognizing that much work remains to clarify the prevalence and impact of MMD.

The myocardial microvasculature actively regulates myocardial blood flow to facilitate delivery of oxygen, nutrients, and hormones to, and removal of metabolic end products from, the myocardium (23). The coronary vasculature includes epicardial coronary and smaller intramyocardial arteries; microvascular arterioles, capillaries and venules; and larger veins leading to the coronary sinus. Within the myocardium, ECs outnumber cardiomyocytes ~3:1 and each mm2 of myocardium contains 3000 to 4000 capillaries which run parallel to the cardiomyocytes (196, 197). The epicardial coronary arteries serve a capacitance function and (absent atherosclerosis) offer little resistance to blood flow (198). Prearterioles (diameter ~100-500 μm) function to maintain pressure within a narrow range in response to changes in perfusion pressure. Proximal prearterioles are most responsive to changes in flow while distal prearterioles are most responsive to changes in pressure (198). Smaller arterioles (diameter <100 μm) are the primary regulators of myocardial blood flow (23, 199) and are characterized by a very large pressure drop along their length. Under normal hemodynamic conditions, resting human left ventricle coronary blood flow averages ~0.7 to 1.0 mL/min/g and can increase 4- to 5-fold during vasodilation in the absence of microcirculatory dysfunction (198, 200).

Inasmuch as vascular tone within the myocardial microcirculation is determined by SMCs, meeting myocardial metabolic demand requires communication from the cardiomyocyte to vascular SMCs and the endothelium. This is accomplished, at least in part, by release of vasoactive metabolites (eg, NO, adenosine, etc.) from the cardiomyocyte and by mechanical changes in the vessel wall which result in increased transmural pressure and enhanced shear stress on the endothelium. A consequence of this is EC depolarization and increased production of NO, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, and hydrogen peroxide (201). The latter vasodilatory signals can be transmitted to nearby SMCs through myoendothelial junctions, analogous to those described previously in skeletal muscle. With the EC coupled to both adjacent SMCs and ECs through gap junctions, localized vasodilation in the areas of increasing metabolic demand can be affected through a vascular network without imposing significant hemodynamic demand. This network pattern results in regional heterogeneity of myocardial blood flow, opening the possibility of localized sites of flow insufficiency if either vasodilatory signals are blunted or vasoconstrictor signals are enhanced. These effects can subsequently produce regional ischemia even in the absence of extramural coronary artery disease (CAD), resulting in ischemic chest pain (ie, microvascular angina) (202).

Endothelial dysfunction and vascular insulin resistance can coexist in the myocardial microcirculation and impair EC NO production, ultimately contributing to myocardial perfusion defects. Clinical studies have shown impaired coronary endothelium-dependent dilation in persons with DM and no significant CAD (203, 204), and this impairment is more marked in type 2 DM patients with microalbuminuria (203). In patients with CAD, type 2 DM independently predicts greater endothelial dysfunction (205). DM in both animals and humans is associated with myocardial microvascular rarefaction and diminished angiogenesis (206). In rodents, obesity, and hypertension likewise provoke myocardial capillary rarefaction (207). In humans, insulin resistance (provoked by lipid infusion) acutely decreases myocardial as well as skeletal muscle microvascular insulin sensitivity (169).

In myocardium, as in other tissues, microvascular functional changes precede structural changes (208-211). The evolving ability to clinically assess early MMD holds great potential for risk stratification and patient therapy. At this time, no clinical imaging technique provides direct visualization of the myocardial microcirculation (212), as both prearterioles and arterioles are below the resolution of current angiographic systems (199, 213). However, myocardial microvascular function can be indirectly assessed using both invasive and noninvasive dynamic techniques (213). Current noninvasive methods include transthoracic Doppler echocardiography, myocardial contrast echocardiography, PET, cardiovascular MRI (CMRI), and computed tomography-derived coronary flow reserve (CFR) (199, 214). Invasive methods include Doppler guidewire-derived coronary blood flow velocity reserve and the index of microcirculatory resistance (199). Each of these techniques have strengths and limitations, and there is no current consensus on a preferred technique. One indirect measure of myocardial microvascular function includes coronary flow responses to vasodilatory stimuli (eg, adenosine, dipyridamole, etc.) with calculation of CFR (ie, the ratio of resting to maximal hyperemic coronary flow) (214). CFR serves as a clinical index of MMD (defined as a CFR <2.0 in the absence of obstructive CAD (214-217)). Currently, PET and CMRI are the most widely used noninvasive methods for measuring myocardial perfusion reserve (218). CMRI in particular has been used to assess MMD in multiple clinical settings, and 2 novel CMRI techniques (stress T1 mapping (219) and myocardial perfusion reserve index (220)) accurately detect MMD when compared with the index of microcirculatory resistance. These noncontrast, noninvasive techniques hold significant potential for MMD and are undergoing large-scale clinical validation (221).

MMD can disrupt normal myocardial blood flow by a combination of functional mechanisms (including EC and SMC dysfunction, inappropriate sympathetic tone, and microvascular atherosclerosis and inflammation (191, 218)) that lead either to impaired dilation or increased constriction of myocardial microvessels (199). These changes limit the myocardial microvasculature’s ability to adapt to changing myocardial oxygen demand (222) and are an early harbinger of more widespread derangement (223, 224). Mounting evidence confirms that MMD impairs myocardial perfusion (191), contributes to the no-reflow phenomenon after revascularization (225), and plays a key role in the development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (226, 227). In DM, MMD correlates significantly with average fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c (204). This DM-induced early microvascular autoregulatory impairment evolves into structural microvascular impairment at later stages of disease (208), with oxidative stress leading to cardiomyocyte stiffening and diastolic dysfunction (228, 229). Tromp et al. recently found that DM microvascular disease is more common in persons with HFpEF than heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, suggesting that HFpEF may be a clinical manifestation of DM microvascular disease (230). Indeed, the emerging paradigm for HFpEF development centers on comorbidities (specifically DM and obesity) driving myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through microvascular endothelial inflammation (223).

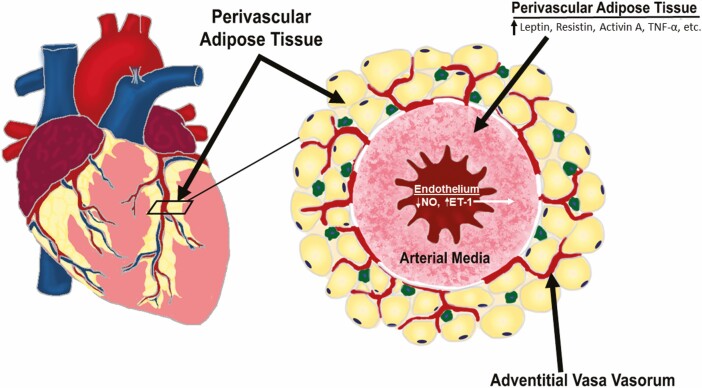

Perivascular adipose tissue within the adventitia of coronary arteries provides a potential link between CAD and MMD. There is a clear association between coronary perivascular adipose tissue (CPVAT) and the pathogenesis of coronary atherosclerosis (231-233), with excess CPVAT recognized as a CVD predictor (234). CPVAT is a naturally occurring visceral adipose tissue that surrounds the major epicardial coronary arteries. It consists of a microvascular network of arterioles, capillaries, and nerve fibers, and contains adipocytes, macrophages, fibroblasts, adipocyte progenitor cells, leukocytes, and mast cells (235-239). Due to the absence of a fascial layer separating it from the coronary arteries, adipokines, and other vasoactive substances secreted by CPVAT can act directly on the underlying SMCs and endothelium of coronary arteries (236, 240-242) to influence vascular tone and blood flow (242). Remarkably, Antonopoulos et al. reported that communication between the vascular wall and CPVAT is bidirectional, with inflammatory mediators and/or oxidation products from a diseased coronary artery able to directly modify the phenotype of perivascular adipocytes (243-245). Obesity, hypertension, and DM induce an imbalance of CPVAT-derived vasoactive products that promotes the infiltration of inflammatory cells (246). This then triggers derangements in coronary vascular SMCs and EC function that promote large artery stiffness and contribute to downstream microvascular dysfunction (Fig. 5). Intriguingly, Cooper et al. have shown that associations between large artery stiffness and CVD events are mediated by pathways that include microvascular damage and remodeling (247). The relationship between CPVAT and coronary macro- and microvascular function appears multidirectional, as coronary adventitial vasa vasorum is interspersed within CPVAT and capable of delivering adventitial derived factors to conduit coronary arteries (which themselves can be regulated by CPVAT) (236, 248). Prior studies have found increased blood flow through the vasa vasorum to the intima of atherosclerotic coronary arteries of monkeys (249), and that neovascularization originating from the adventitia predicts the extent of inflammation and CAD in humans (250).

Figure 5.

CPVAT is located adjacent to various macro- and microvascular surfaces, including coronary arterial media and adventitial vasa vasorum, which enables paracrine secretion of many vasoactive substances. In pathophysiological states (eg, DM and CMD), CPVAT paracrine secretion becomes unbalanced and dysfunctional, resulting in reduced NO bioavailability and enhanced secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines that increase large artery stiffness and contribute to downstream microvascular (ie, vasa vasorum) dysfunction. PVAT, perivascular adipose tissue; DM, diabetes mellitus; CMD, cardiometabolic disease; NO, nitric oxide; ET-1, endothelin-1; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha).

Several recently developed imaging techniques hold great potential for clarifying the potential regulatory role of CPVAT in MMD. Work by Sade et al. found CPVAT thickness was an independent predictor of diminished CFR in women with angiographically normal coronary arteries (251). Ohyama et al. recently used 18F-FDG PET/CT and optical coherence tomography to test the hypothesis that coronary artery spasm is associated with peri- and microvascular inflammation in patients with vasospastic angina (252). Study results confirmed that CPVAT volume, CPVAT FDG uptake, and coronary microvascular vasa vasorum formation were all significantly increased in the vasospastic angina group compared with controls (252). Likewise, the perivascular fat attenuation index (a novel imaging biomarker) provides an estimate of coronary inflammation and enhances cardiovascular risk prediction (253). At this time, only one study has investigated the effect of CPVAT on human myocardial microvascular function in disease states known to cause MMD (eg, DM, obesity, etc.). Zobel et al. recently used cardiac 82Rb PET/CT scanning to compare the total amount of CPVAT to CFR in 30 healthy controls, 60 persons with type 2 DM, and 60 persons with type 1 DM (254). CPVAT was negatively associated with CFR in healthy controls, but no association was observed in those with DM. At this time, the relationship of CPVAT to MMD in DM ± CMD remains unclear and warrants further investigation.

Overall, progress unraveling the pathogenesis of MMD has lagged (255). In particular, contributions of the SNS (which parallels arteriolar and capillary networks throughout the myocardium (256, 257)) to the interplay between the microvasculature and cardiomyocyte is poorly understood. Similarly, the contributions of endothelial dysfunction and microvascular insulin resistance (2 common findings in DM and CMD (258)) to MMD have been little studied. Ideally, future research will clarify these relationships and evaluate novel treatment strategies to determine if they can reliably improve MMD.

Renal microvasculature

Nephropathy is a common, serious, and frequently preventable DM microvascular complication that is a major contributor to end-stage renal disease and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Despite improvements in medical therapy for glycemic and hypertensive control, the prevalence of DM renal disease has changed little over the last 30 years (259).

The earliest pathologic lesion suggestive of DM nephropathy is glomerular BM (GBM) thickening, which positively correlates with hyperglycemia and urine albumin excretion among persons with DM (260). GBM thickening also occurs with age and hypertension in both pre-DM and non-DM patients, thus it may represent a non-specific response to glomerular microvascular injury. As DM glomerular injury progresses, it may advance to mesangial expansion, nodular sclerosis (Kimmelstiel–Wilson lesion) and advanced glomerular sclerosis (260). Additionally, glomerular and peritubular capillary rarefaction, pericyte loss, peritubular fibrosis, and arteriosclerosis all contribute to declining renal function in DM (261). The glomerular capillary tuft has a unique structure comprised of a specialized fenestrated capillary bed between afferent and efferent arterioles that is covered by the vascular BM, which in turn is sheathed by podocyte foot processes. This entire structure sits within Bowman’s capsule, the epithelial lining of which forms the parietal boundary of the extracellular space of the glomerulus containing the urinary filtrate. The pressure within the glomerular capillary (Pglo) is ~4- to 6-fold greater than in capillaries elsewhere and is controlled by the tone of the afferent and efferent arterioles. The elevated Pglo (relative to pressure in Bowman’s space) and fenestrated endothelium allow selective filtration of plasma during passage through the glomerulus. The EC fenestrae are small enough to exclude cellular elements and platelets, and the negative charge of the EC glycocalyx and of the GBM proteoglycans limits filtration of negatively charged plasma proteins. The podocyte foot processes form a near continuum around the BM, with significant adhesion between foot processes formed by specialized adherens-like junctions that also contain tight junction proteins (262). These foot processes are sufficiently extensive to restrict the paracellular passage of proteins while allowing electrolytes, amino acids, urea, creatinine, glucose, and small proteins to enter the urinary filtrate. This occurs via discontinuities between adjacent foot processes known as filtration slits. These slits are covered by a proteinaceous diaphragm which contributes to the selective exclusion of proteins from the urinary filtrate, with injury to podocyte slit processes recognized as a major contributor to the proteinuria seen in DM and other forms of nephropathy. In the kidney, it appears to be concerted dysfunction of the endothelium and adjoining support cells (eg, podocytes, mesangial cells, fibroblasts, etc.) that leads to significant clinical dysfunction. Notably, systemic capillary rarefaction correlates with increased incidence of microalbuminuria in a middle-aged population-based study from The Netherlands (263). Peritubular capillary rarefaction may produce tubular epithelial hypoxic injury and inflammation due to the high energy requirements of the proximal tubule epithelium (264).

Microalbuminuria, proteinuria, and creatinine clearance changes provide useful clinical indicators of both renal injury and responses to therapy. However, since it takes a decade or more of DM before these variables are affected, it is important to question whether there are functional abnormalities that could identify at-risk individuals. In particular, the responsiveness of proteinuria to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (265) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (266, 267) correlates reasonably well with preservation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR). These agents act principally by blocking angiotensin II’s action to vasoconstrict the glomerular efferent arteriole, thereby decreasing Pglo. Furthermore, good control of other metabolic and hemodynamic factors (eg, plasma glucose and lipids, blood pressure, etc.) is associated with slowed progression and even reversal of microalbuminuria (268). However, it is increasingly appreciated that some individuals with DM experience significant declines in renal function without developing significant proteinuria (269). In this scenario, injury to the proximal tubules may be contributing. To meet the need for identification of additional clinically relevant biomarkers that predict onset or progression of renal dysfunction beyond what is available from measurements of albuminuria and GFR, several tubular proteins (ie, KIM-1, L-FABP, TNFR-1, and NAG) have been studied (264, 270). Unfortunately, to date these studies have produced variable results and failed to demonstrate clinical utility in DM.

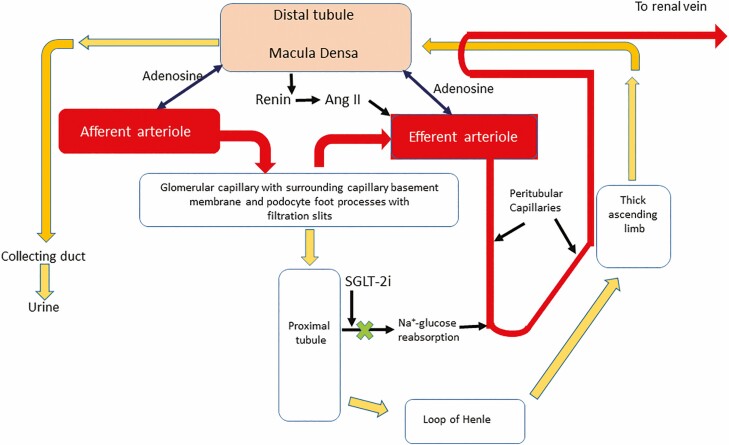

Several large clinical trials have recently shown that sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition (SGLT2i) can significantly improve proteinuria and slow GFR decline in type 2 DM (271-274). The mechanism for this striking renal effect (as well as the CVD benefit of these agents) remains uncertain. However, several careful studies have suggested that blocking proximal tubular glucose and sodium absorption by SGLT2i causes increased delivery of glucose and sodium to the macula densa of the distal tubule (Fig. 6). This leads to either afferent arteriolar constriction (275) or efferent arteriolar relaxation (271, 276) and a net decline of Pglo, hence a decline of capillary-to-Bowman’s space pressure gradient and a decreased filtration fraction. These effects result in an acute 3–4 mL/min fall in GFR but a significant slowing of the long-term decline in GFR. This tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism provides a pathway for regulating both single nephron and whole kidney GFR. For example, SGLT2i increases afferent arteriolar tone in type 1 DM subjects with significant whole kidney hyperfiltration, which thereby decreases renal plasma flow and can markedly decrease GFR (275). Of note, hyperfiltration is a known risk factor for GFR decline, perhaps secondary to increased Pglo and shear stress on the glomerular endothelium. By contrast, data on the mechanism of SGLT2i’s renoprotective effect in type 2 DM suggest that, like ACE inhibitors, they act principally to dilate the efferent arteriole. Importantly, SGLT2i is effective even in patients on ACE inhibitors or ARBs. Recent studies have shown that SGLT2i may also prevent proximal tubular hypoxemic injury by decreasing metabolic demands of proximal tubular sodium and glucose transport (264).

Figure 6.

Studies of the renal microvascular effects of diabetes mellitus and cardiometabolic disease have long focused on glomerular injury and control of glomerular perfusion by regulation of afferent and efferent arteriolar tone. In particular, blocking angiotensin II-induced efferent arteriole constriction and reducing glomerular capillary pressure has been a therapeutic mainstay. The beneficial effects of SGLT-2 inhibition on renal function may relate in part to increased sodium delivery to the macula densa of the distal tubule, with resulting decreased renin production and angiotensin II generation. Further renal benefit may derive from (1) decreased energy expenditure for sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubule, lessening oxygen consumption from peritubular postglomerular capillaries and diminishing renal cortical hypoxic stress, epithelial cell apoptosis and tubular fibrosis, and (2) from increased adenosine release at the macula densa which acts to vasoconstrict the afferent and vasodilate the efferent arteriole. Ang II, angiotensin II; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibition.

While the impact of SGLT2i on renal function is impressive, it remains the case that patients treated with these agents still often experience deteriorating renal function. The complex multicellular organization of the glomerulus, the complex interplay of glomerular and tubular functions, the population heterogeneity regarding the risk of developing nephropathy in human DM, and the lack of excellent rodent models for advanced DM kidney disease have challenged efforts to unravel the cellular pathways involved in the development of DM nephropathy and hence identify therapeutic targets. Thus, while several large genome-wide association studies have identified loci associated with increased nephropathy risk in distinct populations (277, 278), many of these loci associate with noncoding regions and may be transcriptional regulatory sites or sites of epigenetic modification. To date, no clear gene target contributing to disease development or presenting the opportunity for directed intervention has been identified. Perhaps adding uncertainty to this, a recent study of STZ-induced DM mice found that while overproduction of ROS by mitochondria or NADPH oxidase is considered a hallmark for the development of DM microvascular complications, ROS production within the kidney in vivo and within podocytes and glomerular EC was not increased (279). Whether this finding in a STZ-treated murine model relates to human DM is uncertain. It remains a significant caveat that while in animal models renal injury with proteinuria occurs early after development of DM, in humans it requires ~8 to 20 years or longer (16).

The SNS also plays a regulatory role in the renal microvasculature, principally via adrenergic nerves directly affecting tone in the renal artery, cortical afferent and efferent arterioles (and consequently GFR), and renin release. The SNS also increases tubular sodium and water reabsorption which subsequently increases blood volume and pressure. In the past decade, catheter-based procedures for renal sympathetic denervation to treat resistant hypertension have been extensively studied and may provide another significant serendipitous finding. In a careful pilot study of resistant hypertensive subjects who were obese and insulin resistant, Mahfoud et al. showed that bilateral renal sympathetic ablation lowered pressure, improved fasting glucose, decreased fasting insulin and c-peptide, and improved indices of insulin sensitivity (ie, HOMA-IR and QUICKI) (280). This occurred in the absence of significant weight loss. The mechanism by which renal sympathetic nerve ablation produced salutary systemic metabolic effects is unclear but deserving of further investigation.

Changes in podocyte structure are also implicated in the deterioration of renal function in a number of glomerular disorders (281). The podocyte plasma membrane includes receptors for numerous circulating factors, some of which (eg, angiotensin II, VEGF, etc.) can directly affect podocyte function. Interestingly, the insulin receptor in podocytes appears critical to normal glomerular function, and selective podocyte knockout of this receptor alters the podocyte cytoskeleton resulting in severe proteinuria and increased glomerular sclerosis (282). This occurs even in the absence of hyperglycemia and may in part explain the increased frequency of proteinuria seen in insulin-resistant obese and CMD subjects who are not hyperglycemic. Kidneys of mice with severe DM have fewer podocytes, and these podocytes have increased concentrations of the lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal (indicating oxidative stress) (283). Indeed, podocyte loss also occurs in humans with DM (284). Podocytes and podocyte marker proteins are found in urine of type 2 DM subjects, and the quantity is greater in subjects with macroalbuminuria than in healthy controls (285).

Almost certainly there is a dynamic interaction between podocytes and ECs that affects glomerular filtration properties. Potentially interesting examples of this include the observation that the podocyte makes VEGFa and has VEGF2R on its surface. VEGF2R can form dimers with nephrin (a major component of the filtration slit diaphragm) upon phosphorylation of the intracellular domain of each (286). This in turn can regulate the actin cytoskeleton of the podocyte, thereby altering the geometry of filtration slits and protein filtration. In considering linkages between GFR and metabolic disorders, it was shown over a decade ago that knockout of adiponectin could induce proteinuria and that supplementing adiponectin prevented this effect (287). In a separate study examining glomeruli of mice genetically modified to accelerate podocyte apoptosis, overexpression of adiponectin was protective while knockdown of adiponectin accelerated podocyte loss (288). These beneficial effects of adiponectin were also seen in STZ-induced DM Wistar rats, suggesting it may have more broad applicability (289). Plasma adiponectin levels tend to rise in individuals with types 1 or 2 DM and nephropathy. Whether this indicates increased production by adipose tissue or decreased clearance by the kidney is uncertain. It may also be a compensatory mechanism in effort to maintain residual renal function. Both the EC and podocyte process express adiponectin receptors, and adiponectin supplementation appears to enhance endothelial function by increasing NO production and decreasing podocyte loss (290).

DM nephropathy remains a difficult clinical challenge, as it occurs commonly and is insidious in its early stages. For those affected, it significantly impacts both quality and duration of life. We currently lack early biochemical or genetic markers to identify those at highest risk who may benefit from aggressive preventive therapies (either established or experimental). Identification of such markers would be a significant step towards reducing the burden of renal disease in persons with DM ± CMD.

Avenues for Future Investigation

As outlined here, microvascular dysfunction occurs in multiple organs and tissue depots throughout the body in established DM. Importantly, anatomical disease is preceded by a long interval of microvascular dysfunction in persons with DM, and similar dysfunction is also observed in individuals with prediabetes or insulin resistance without hyperglycemia. The latter has become apparent as methodologies have developed to test the functional integrity of the microvasculature in various tissues. The observation that in multiple tissues microvascular dysfunction can be provoked acutely by raising circulating concentrations of free fatty acids, glucose, or cytokines is consistent with the ability of these factors to stimulate production of ROS and AGEs in short-term cell culture or with DM of acute or subacute duration in animal models.