Abstract

Background

The influence of aging and multimorbidity on Covid-19 clinical presentation is still unclear.

Objectives

We investigated whether the association between symptoms (or cluster of symptoms) and positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) was different according to patients’ age and presence of multimorbidity.

Methods

The study included 6680 participants in the EPICOVID19 web-based survey, who reported information about symptoms from February to June 2020 and who underwent at least one NPS. Symptom clusters were identified through hierarchical cluster analysis. The associations between symptoms (and clusters of symptoms) and positive NPS were investigated through multivariable binary logistic regression in the sample stratified by age (<65 vs ≥65 years) and number of chronic diseases (0 vs 1 vs ≥2).

Results

The direct association between taste/smell disorders and positive NPS was weaker in older and multimorbid patients than in their younger and healthier counterparts. Having reported no symptoms reduced the chance of positive NPS by 86% in younger (95%CI: 0.11-0.18), and by 46% in older participants (95%CI: 0.37-0.79). Of the four symptom clusters identified (asymptomatic, generic, flu-like, and combined generic and flu-like symptoms), those associated with a higher probability of SARS-CoV-2 infection were the flu-like for older people, and the combined generic and flu-like for the younger ones.

Conclusions

Older age and pre-existing chronic diseases may influence the clinical presentation of Covid-19. Symptoms at disease onset tend to aggregate differently by age. New diagnostic algorithms considering age and chronic conditions may ease Covid-19 diagnosis and optimize health resources allocation.

Trial registration

NCT04471701 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Keywords: COVID-19, Symptom Cluster, Differential Diagnosis, Aged, Multimorbidity Abbreviations SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab - NPS, European Union General Data Protection Regulation - EU GDPR, Odds ratios – OR, 95% confidence intervals - CIs

1. Introduction

The burden posed by the Covid-19 pandemic on healthcare systems requires strategies to identify high-risk people in order to better allocate the available health resources and plan targeted care pathways [1]. Despite the growing evidence on the field, the heterogeneity of Covid-19 both in terms of clinical presentation has not yet made possible to disentangle the complexity of such disease [2], [3], [4].

Considering the clinical presentation of Covid-19, a first issue lies in the poor specificity of the symptoms mostly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection [5], [6], [7] and in the presence, on the other hand, of possible atypical or asymptomatic disease onset [2,5,8,9]. As a matter of fact, most of the identified signs and symptoms, such as fever, cough, or myalgia, can be also suggestive of influenza or of other common respiratory infections, and this can complicate the differential diagnosis of Covid-19 in the autumn and winter seasons [10,11]. An alternative and helpful approach would be therefore to consider not only the single symptoms, but their tendency to aggregate and determine different disease phenotypes. Following this line, the work of Sudre et al found a variability in the need of high-level medical support across different clusters of symptoms longitudinally reported by COVID-19 patients [12]. However, considering the diagnostic phase of the disease, the extent to which each cluster of symptoms may be predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection has not yet been investigated.

A second issue concerns the identification of the factors that may influence the heterogeneity of Covid-19 onset. In this regard, advanced age and pre-existing chronic diseases, two strictly related aspects [13], have shown to substantially impact on Covid-19 prognosis leading to dramatic increases in case-fatality rates [14], [15], [16]. However, despite some case reports suggesting the occurrence of atypical Covid-19 presentation in older people [9], to date it is still unclear to which extent older age and multimorbidity can influence the symptoms pattern at the disease onset.

In this study, we hypothesized that age and multimorbidity can influence the clinical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Moreover, we supposed that the ways through which symptoms tend to aggregate together can define different symptom clusters, which may be more or less strongly predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adult and older individuals.

The aims of this work were therefore to investigate whether the association between symptoms (or cluster of symptoms) and positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) was different according to patients’ age and presence of multimorbidity.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design and study population

This work analyses data from the EPICOVID19 web-based survey, which was launched on 13 April 2020 and involved Italian volunteers aged 18 years or older [5]. The survey was promoted via social media (Whatsapp, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram), link in institutional websites, press releases, radio and television stations [5]. The online survey was implemented using questions with close-ended answers to facilitate the questionnaire compilation and to avoid errors in digitizing answer values. Inclusion criteria for participation in the survey were: being aged ≥18 years; having the possibility to access to a mobile phone, computer, or tablet with internet connectivity; and giving the on-line informed consent for participating in the survey. For the purpose of this study, from the 198,828 survey respondents up to June 2020 (mean age 48 [SD 14.7] years, 40.3% men), we excluded 191,514 individuals who had never been tested with a SARS-CoV-2 NPS, and 634 who had undergone a NPS but did not know the result of the test.

The EPICOVID19 study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Istituto Nazionale per le Malattie Infettive I.R.C.C.S. Lazzaro Spallanzani (Protocol No. 70, 12/4/2020). Informed consent was accessible on the home page of the platform and participants, on the first access to the on-line platform, were asked to review before starting the compilation, thus explaining the purpose of the study and which data were to be collected and how data were stored. The study complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data were handled and stored in accordance with the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679 [17]. In particular, data were stored in a file server firewalled within the ITB-CNR intranet. For privacy and security reasons, the access to the database is protected with a password granted only to the server administrator. In the final dataset a unique key identifies each subject to guarantee anonymity. Personal data are regarded as strictly confidential and removed before the exportation procedure. Security of data is guarantee via automatic backups. The study was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04471701).

2.2. Data collection

The 38-item EPICOVID19 questionnaire collected the following information: socio-demographic characteristics; clinical evaluation; personal information and health status; housing conditions; lifestyle; and behaviors following the lockdown [5]. For this study, in particular, we considered socio-demographic data, namely age, sex, and educational level (classified as low [primary school or less], middle [middle or high school], and high [university/post-graduate degree]). As for health behaviors, we considered self-reported smoking habit, categorized as never, former or current habit. Respondents’ area of residence was classified as Italian regions, Republic of San Marino, other countries, and unknown. We categorized Italian regions into four areas according to the ratio between (total nasopharyngeal swabs [NPS] performed / total individuals tested at least once) / (total COVID-19 cases / total individuals tested at least once), using national data [18]. The numerator of this ratio indicates the availability of resources to perform NPS in each region, while the denominator provides a measure of the disease prevalence in that region. From the ratio between these elements, it is estimated the availability of NPS taking into consideration the COVID-19 prevalence in each region. The higher the ratio, the greater the local resources allocated for NPS test. The areas classified based on the ranking of that ratio, in ascending order, were: Area 1: Piedmont, Lombardy, Aosta Valley, Emilia Romagna, Liguria and Marche; Area 2: Tuscany, Trentino Alto Adige, Abruzzo, Apulia; Area 3: Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Lazio, Molise, Campania; Area 4: Sicily, Sardinia, Umbria, Calabria and Basilicata.

Based on self-reported information on chronic diseases and regularly taken medications, we defined the presence of respiratory diseases, arterial hypertension, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes pharmacologically treated, chronic kidney disease, immunologic diseases, cancer, metabolic diseases (excluding diabetes), liver diseases, thyroid diseases pharmacologically treated, and depression and/or anxiety. From the sum of these chronic conditions, we computed the total number of diseases, categorized as none, one, and ≥2. The regular use of anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids was also considered for the present analysis.

Of the data collected about COVID-19, in this study we considered:

-

a)

self-reported symptoms from February 2020, including: fever of >37.5° for at least three consecutive days, cough, headache, myalgia, olfactory or taste disorders, shortness of breath, sore throat/rhinorrhea, chest pain, heart palpitations, gastrointestinal disturbances, and conjunctivitis;

-

b)

month at the onset of the reported symptoms (February, March, April, or May);

-

c)

Access to a SARS-CoV-2 NPS testing and its positive or negative result.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the sample as a whole and by age are described as mean (standard deviation, SD) for the continuous variables, and as counts and percentages for the categorical ones. The frequency of self-reported symptoms was compared between individuals with positive vs negative NPS by Chi-squared test. The chance of having a positive SARS-CoV-2 NPS was assessed through multivariable binary logistic regression adjusted for age and sex (Model 1) and then for additional potential confounders: smoking habit, number of chronic diseases, CVD, respiratory diseases, diabetes, depressive/anxiety disorders, use of steroids, use of anti-inflammatory drugs, month at symptoms onset, and geographical area (Model 2). To investigate the possible modifying effect of age (< or ≥65 years) and number of chronic diseases (0, 1 or ≥2) on the association between symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 NPS result, we performed stratified analyses, as appropriate.

We evaluated the presence of “clusters” of symptoms using a hierarchical cluster analysis on variables and evaluating the obtained dendrogram. For this analysis, we considered the proportion of observations for which two variables are both positive as similarity measures. The frequency of positive SARS-CoV-2 NPS result within each symptom cluster was compared between individuals < vs ≥65 years through the Chi-squared test. The association between each symptom cluster (compared with all the others) and positive SARS-CoV-2 NPS result was evaluated by calculating odds ratios (OR) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To explore the presence of possible age-related differences, the analysis was stratified by age. Analyses were considered as statistically significant with a two-tails p-value <0.05 and were performed using R version 3.6.3 [19].

3. Results

The study sample included 6680 adults (mean age 47.9 [SD 14.0] years, 34.3% men), whose characteristics are shown in Table 1 . As reported, around 70% of the sample, especially in those aged <65 years, had a high educational level. The prevalence of individuals with ≥2 chronic diseases ranged from 16.2% in the younger participants (7.8% and 22.9% for the <45 and 45-64 years groups, respectively), to 60.4% in those ≥65 years. The three most frequent diseases in the younger group were arterial hypertension, immunologic and respiratory diseases; while, in the older group were arterial hypertension, CVD, and metabolic diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample as a whole and by age (n=6680).

| Age | |||

| All | <65 years | ≥65 years | |

| n | 6680 (100.0) | 6061 (90.7) | 619 (9.3) |

| Sex (male) | 2292 (34.3) | 1980 (32.7) | 312 (50.4) |

| Age (years) | 47.87 (14.04) | 45.18 (11.42) | 74.23 (9.22) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| European | 6617 (99.1) | 5999 (99.0) | 618 (99.8) |

| Non-European | 63 (0.9) | 62 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Educational level | |||

| Low | 512 (7.7) | 341 (5.6) | 171 (27.6) |

| Middle | 1446 (21.6) | 1305 (21.5) | 141 (22.8) |

| High | 4722 (70.7) | 4415 (72.8) | 307 (49.6) |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Never | 4213 (63.1) | 3841 (63.4) | 372 (60.1) |

| Former | 1428 (21.4) | 1238 (20.4) | 190 (30.7) |

| Current | 1039 (15.6) | 982 (16.2) | 57 (9.2) |

| Chronic diseases (number) | |||

| 0 | 3650 (54.6) | 3564 (58.8) | 86 (13.9) |

| 1 | 1677 (25.1) | 1518 (25.0) | 159 (25.7) |

| 2+ | 1353 (20.3) | 979 (16.2) | 374 (60.4) |

| Respiratory diseases | 531 (7.9) | 445 (7.3) | 86 (13.9) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 532 (8.0) | 283 (4.7) | 249 (40.2) |

| Arterial hypertension | 1168 (17.5) | 836 (13.8) | 332 (53.6) |

| Diabetes | 163 (2.4) | 107 (1.8) | 56 (9.0) |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 76 (1.1) | 43 (0.7) | 33 (5.3) |

| Immunologic diseases | 654 (9.8) | 590 (9.7) | 64 (10.3) |

| Cancer | 220 (3.3) | 150 (2.5) | 70 (11.3) |

| Metabolic diseases | 570 (8.5) | 407 (6.7) | 163 (26.3) |

| Liver diseases | 59 (0.9) | 45 (0.7) | 14 (2.3) |

| Depression-anxiety | 498 (7.5) | 398 (6.6) | 100 (16.2) |

| Major surgery in the last year | 282 (4.2) | 235 (3.9) | 47 (7.6) |

| Transplant | 19 (0.3) | 16 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) |

| Use of steroids | 151 (2.3) | 132 (2.2) | 19 (3.1) |

| Use of anti-inflammatory drugs | 422 (6.3) | 384 (6.3) | 38 (6.1) |

| Dependency in daily activities | 220 (3.3) | 89 (1.5) | 131 (21.2) |

| Geographical area | |||

| Area 1 | 3624 (54.8) | 3190 (53.1) | 434 (70.7) |

| Area 2 | 777 (11.7) | 719 (12.0) | 58 (9.4) |

| Area 3 | 1871 (28.3) | 1771 (29.5) | 100 (16.3) |

| Area 4 | 328 (5.0) | 308 (5.1) | 20 (3.2) |

| Other | 18 (0.3) | 16 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Month at symptoms’ onset | |||

| No symptoms | 1740 (26.0) | 1527 (25.2) | 213 (34.4) |

| February | 1662 (24.9) | 1566 (25.8) | 96 (15.5) |

| March | 2847 (42.6) | 2610 (43.1) | 237 (38.3) |

| April | 420 (6.3) | 351 (5.8) | 69 (11.1) |

| May | 11 (0.2) | 7 (0.1) | 4 (0.6) |

| Positive SARS-CoV-2 NPS | 1676 (25.1) | 1356 (22.4) | 320 (51.7) |

Notes. Area 1 includes Piedmont, Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Liguria, Marche, and Aosta Valley. Area 2 includes Tuscany, Trentino Alto Adige, and Apulia. Area 3 includes Veneto, Lazio, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Molise, and Campania. Area 4 includes Sicily, Sardinia, Umbria, Calabria, and Basilicata. Other includes Republic of San Marino, other countries, and unknown. Abbreviations: NPS, nasopharyngeal swab.

3.1. Symptoms, age and positive NPS

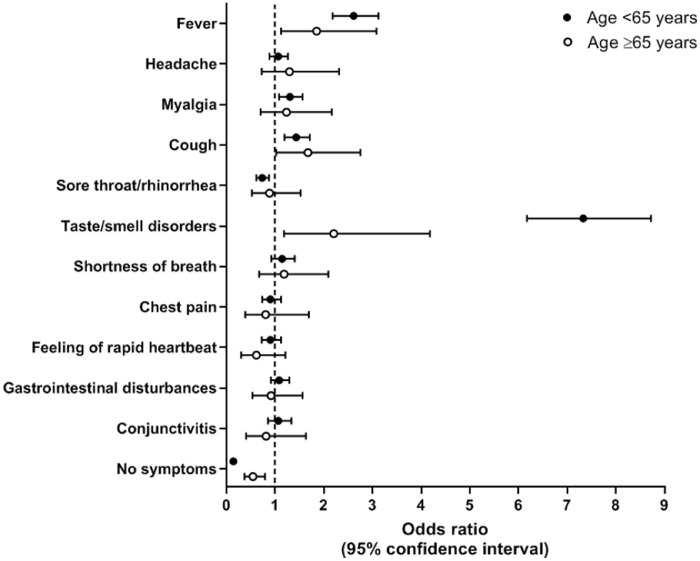

Since February 2020, the symptoms most frequently reported by the younger respondents were headache (39.4%), myalgia (35.6%), cough (35.2%), and sore throat/rhinorrhea (38.6%). In the older ones, the most reported symptoms were fever (39.6%), cough (28.6%) and myalgia (24.2%) (Supplementary Table S1). At logistic regression, after adjusting for potential confounders (Fig. 1 , Supplementary Table S2), we found that having had fever (OR=2.61, 95% CI: 2.18-3.12), myalgia (OR=1.30, 95% CI: 1.08-1.56), cough (OR=1.43, 95% CI: 1.19-1.71) and taste or smell disorders (OR=7.33, 95% CI: 6.17-8.72) were significantly associated with a positive SARS-CoV-2 NPS test result in individuals <65 years. Among the older group, significant direct associations with positive NPS were observed for fever (OR=1.85, 95% CI: 1.12-3.08), cough (OR=1.67, 95% CI: 1.02-2.75), and taste or smell disorders (OR=2.20, 95% CI: 1.18-4.18). Having reported no symptoms was associated with a chance of having a positive NPS reduced by 86% in younger participants (OR=0.14, 95% CI: 0.11-0.18), and by 46% in the older ones (OR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.37-0.79).

Fig. 1.

Association between symptoms and positive nasopharyngeal swab test in young and older people.

Notes. Odds ratios derive from a binary logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, smoking habit, number of chronic diseases (0 vs 1 vs 2+), cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, diabetes, depressive/anxiety disorders, use of steroids, use of anti-inflammatory drugs, month at symptoms onset, and geographical area. Except for analysis on “no symptoms”, all symptoms were included in the model. The outcome was having had a positive nasopharyngeal swab test.

3.2. Symptoms, number of comorbidities and positive NPS

When evaluating the association between reported symptoms and NPS result in the sample stratified by number of chronic diseases (Supplementary Table S3), we found that fever and taste or smell disorders were associated with positive NPS in all groups, although the association for the latter symptom attenuated from those who had no diseases (OR=7.69, 95% CI: 6.16-9.63) to those with ≥2 diseases (OR=4.56, 95% CI: 3.04-6.86). Instead, myalgia was associated with positive NPS only among those with no diseases (OR=1.44, 95% CI: 1.14-1.83), while cough only among those with one (OR=1.95, 95% CI: 1.41-2.71) and ≥2 diseases (OR=2.93, 95% CI: 1.38-2.97). Finally, having reported no symptoms was associated with a chance of having a positive NPS reduced by around 85% in the groups with none or one disease, and by 57% in individuals with multimorbidity.

3.3. Clusters of symptoms and positive NPS

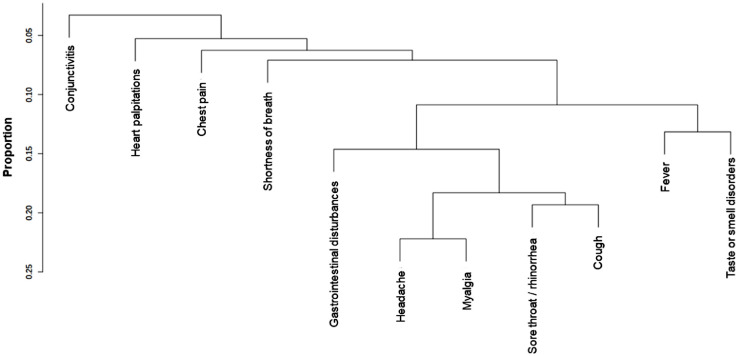

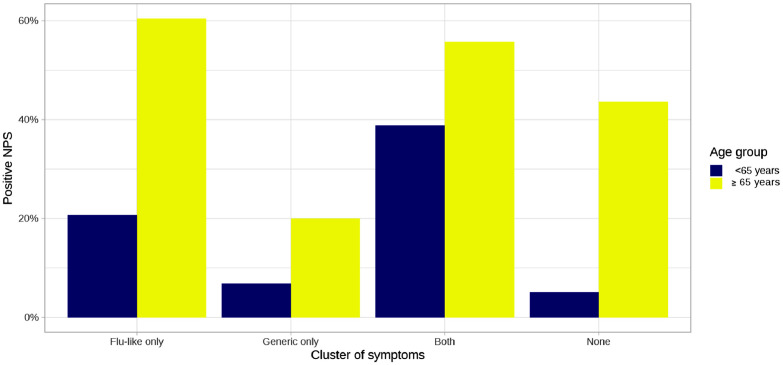

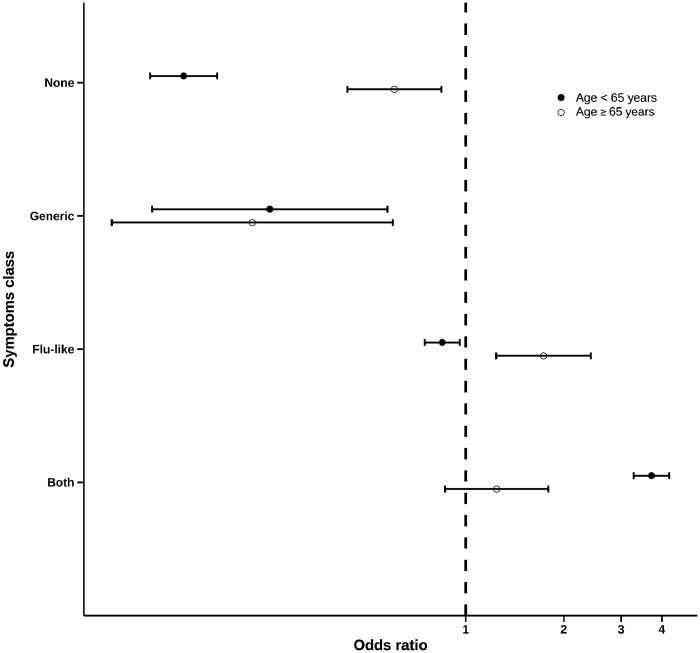

The dendrogram illustrating the clusters of symptoms identified in our sample is shown in Fig. 2 . The frequency of participants who reported only flu-like symptoms (fever, smell or taste disorders, cough, sore throat/rhinorrhea, myalgia, headache, gastrointestinal disturbances) was 40.6%, and for only generic symptoms (shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, conjunctivitis) it was 1.7%; in 31.5% of cases, individuals reported both flu-like and generic symptoms, while 26.2% did not report any symptom (for the distribution of symptoms clusters, alone and in combination, please to see Supplementary Figure S1). As illustrated in Fig. 3 , the frequency of positive SARS-CoV-2 NPS test in each symptom cluster was higher in the older than in the young individuals, especially considering those who reported only flu-like symptoms (60.4% vs 20.7% in older and younger participants, respectively, p<0.001) and no symptoms (43.6% vs 5.1%, p<0.001). Participants with only generic symptoms had a lower probability of a positive NPS compared with the other clusters, without differences between younger (OR=0.25, 95% CI: 0.11-0.57) and older (OR=0.22, 95% CI: 0.08-0.60) respondents (Fig. 4 ). The flu-like cluster of symptoms was associated with a probability of having a positive NPS reduced by 15% (OR=0.85, 95% CI: 0.75-0.96) in young respondents, and increased by 73% (OR=1.73, 95% CI: 1.24-2.42) in older individuals. A significant higher chance of having a positive NPS was found in young individuals with combined flu-like and generic symptoms (OR=3.72, 95% CI: 3.28-4.22), while no significant results were found for the older participants. Finally, lack of symptoms was associated with a 86% percent reduction of the odds of having a positive NPS (OR=0.14, 95% CI: 0.11-0.17) in asymptomatic young individuals, compared to a 40% reduction in older people (OR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.43-0.84).

Fig. 2.

Dendrogram of symptom clusters reported among the 6680 respondents.

Notes. Fever, smell or taste disorders, cough, sore throat/rhinorrhea, myalgia, headache, and gastrointestinal disturbances defined the flu-like symptoms cluster. Shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, and conjunctivitis defined the generic symptoms cluster.

Fig. 3.

Frequency of positive SARS-CoV-2 nasopharyngeal swab test in young and older individuals stratified by symptom cluster.

Abbreviations: NPS, nasopharyngeal swab.

Fig. 4.

Logistic regression for the association between symptom clusters and positive nasopharyngeal swab test.

Notes. Odds ratios derive from an unadjusted binary logistic regression. Symptom clusters (vs all the others) were considered separately as exposure. The outcome was having had a positive nasopharyngeal swab test.

4.Discussion

Our study found that age and pre-existing chronic diseases may influence the clinical presentation of Covid-19. Moreover, from the set of reported symptoms, four clusters were identified: asymptomatic, generic, flu-like, and combined generic and flu-like symptoms. Age seemed to substantially modify the association between symptom clusters and the chance of having a positive NPS.

In line with our previous works [5,20], we found that in individuals aged <65 years, the symptoms more strongly associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection were taste or smell disorders, fever, cough, and myalgia. The picture slightly changed in older participants since in this group myalgia was not associated with positive NPS, while fever and especially taste or smell disorders showed much weaker associations than those observed in younger individuals. When participants were stratified by the presence of chronic diseases, we found that myalgia was predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection only in the healthiest ones, while cough was more strongly associated with higher chances of positive NPS in those with chronic diseases. As for older age, the association between taste or smell disorders and positive NPS weakened for increasing number of comorbidities. Instead, reporting no symptoms reduced the chance of positive NPS much more in the younger and the healthiest participants than in the older and in the multimorbid ones, despite this data could have been influenced by the differential involvement of individuals in screening procedures. Finally, no significant results were found for gastrointestinal disturbances, irrespective of age and of the number of chronic diseases.

Overall, these findings confirm that the identification of infectious diseases, such as Covid-19, may be harder in older people and in individuals with high clinical complexity. Indeed, also in common infections such as influenza or pneumonia, older individuals often present attenuated symptoms or atypical disease presentations characterized, for example, by the sudden occurrence of falls, confusion, or anorexia, which sometimes are undervalued by the visiting physicians [21,22]. In accordance with these observations, several authors found that only one third of older adults with influenza met the ongoing clinical criteria to define influenza-like illness [23], while considering community-acquired pneumonia, only 50% of older patients presented the typical combination of fever, cough and dyspnea, and 10% did not report any symptom [24]. This issue needs to be taken into account when planning diagnostic procedures for people of different ages, since the indication to perform diagnostic test for SARS-CoV-2 infection should be considered also in older individuals with non-specific or absent symptoms.

Possible mechanisms underlying the age-related variability in the clinical presentation of infectious diseases lie in the changes in the immune response, including cytokines’ production and thermoregulation processes, which may buffer the onset of symptoms like fever, myalgia or sore throat/rhinorrhea [21,[25], [26], [27]]. The presence of a chronic inflammatory status due to pre-existing diseases, moreover, may be an additional factor determining a poor predictive value of some clinical parameters, e.g., fever and myalgia, for the diagnosis of common infections [28]. At the same time, the clinical presentation of acute diseases can be influenced also by the unbalance of chronic conditions [22]. This was likely to be the case, in our sample, of cough, which was associated with a positive NPS only in individuals with chronic diseases.

A novel finding of our study concerns the weaker association of taste and smell disorders [29] with SARS-CoV-2 infection in advanced age and in individuals with a higher number of comorbidities. As regards older age, these results can be supported by the aging-related impairments both in olfactory and taste senses caused by structural and functional changes [30,31] and possibly exacerbated by longer exposure to smoke or environmental toxic substances [32,33]. Although this issue deserves deeper investigations, pre-existing impairments could make older individuals lesser sensitive to the olfactory and taste disorders caused by SARS-CoV-2, resulting in a weaker association between such symptoms and positive NPS.

A further factor to be considered concerns the chronic drug therapies. Indeed, the use of special classes of medications or of multiple drugs can not only buffer the occurrence of symptoms like fever or myalgia [21], but may also lead to chemosensory alterations that may impair smell and taste senses [34]. This point could justify the progressive attenuation in the association between taste and smell disorders with positive NPS in individuals with a higher number of chronic diseases (who were therefore likely to use an increasing number of medications), which was confirmed even after adjusting for age.

In a second phase of the study, we considered the tendency of symptoms to aggregate and present together, identifying four symptom clusters. In particular, among the survey respondents, around 40% reported only flu-like symptoms (including fever, smell or taste disorders, cough, sore throat/rhinorrhea, myalgia, headache, and gastrointestinal disturbances), almost 2% only generic symptoms (including shortness of breath, chest pain, heart palpitations, and conjunctivitis), one third both flu-like and generic symptoms, while more than 25% did not report any symptom. Of these symptom clusters, the flu-like one was found to be associated with a chance of having a positive NPS increased in people aged ≥65 years and reduced in those <65 years, while the cluster with combined generic and flu-like symptoms was associated with a higher probability of SARS-CoV-2 infection only in younger individuals. Conversely, individuals with only generic symptoms or asymptomatic had a lower probability of positive NPS in both age classes, despite the latter cluster demonstrated weaker results in the older ones.

To our knowledge, one recent study evaluated clusters of symptoms longitudinally reported by Covid-19 patients in respect to the need of intensive care [12]. Although the sample of that work included only Covid-19 patients who were on average younger than our participants, some similarities with our findings can be noted. In particular, in that study the clusters mostly associated with higher need of medical support were characterized by an earlier presentation of combined flu-like and generic symptoms, which corresponds to the cluster most indicative of Covid-19 in our younger participants. Instead, for older age it could be argued that generic symptoms were mostly related to pre-existing chronic conditions, so that more specific clinical parameters, such as fever, cough, and taste or smell disorders, could have had a heavier weight in determining the probability of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Despite the need of further studies to corroborate our results and to explore the ways through which different symptom clusters are associated with the presence and prognosis of Covid-19, we think that these findings could have useful clinical implications to facilitate the diagnostic process of such disease in adult and older individuals. Indeed, our study suggests that algorithms considering both the presence of symptoms, alone or in combination, and the individual characteristics, may help in improving the identification of suspected Covid-19 cases, to whom address appropriate diagnostic testing.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Among the limitations of this study, the use of self-reported data needs to be considered as a possible source of recall bias. Moreover, although the use of a web-based survey allowed us to involve a large sample of individuals, this way of questionnaire administration could have led to select only people with high technological abilities. This issue could have limited the generalizability of our results, in particular for the oldest old. Indeed, the proportion of people aged ≥65 years was lower in our sample respect to the Italian general population (9.3% vs 22.7%). The mean age (and standard deviation) of such category was 74.2 (SD 9.2) years, indicating that only a minority of our participants were aged 80 years or older. On the other hand, strengths of the work lie in the approach used to identify symptom clusters and in the wide set of information collected for each survey participant.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that age and chronic diseases can substantially influence the clinical presentation of Covid-19. Symptoms at disease onset tend to aggregate defining specific clusters which may present further differences by age. These findings support the need of elaborating dedicated diagnostic algorithms that considering individual characteristics like age and chronic diseases, may improve the diagnostic process of Covid-19 and the related healthcare resources allocation.

Author's contribution

Responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole: Trevisan, Prinelli, Adorni, Antonelli Incalzi, Pedone had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Trevisan, Noale, Prinelli, Maggi, Di Bari, Adorni, Antonelli Incalzi, Pedone

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors

Drafting of the manuscript: Trevisan, Pedone, Antonelli Incalzi.

Critical revision and editing of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Statistical analysis: Trevisan, Noale, Pedone

Supervision: Maggi, Di Bari, Galli, Antonelli Incalzi, Pedone

Final approval of the version to be published: All authors

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding

None

Share your research data

Data will be made available on request

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study and made it possible.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2021.01.028.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Volpato S, Landi F, Incalzi RA. A Frail Health Care System for an Old Population: Lesson form the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;XX:1–2. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glaa087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang BY, Barnard LM, Emert JM, Drucker C, Schwarcz L, Counts CR. Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Receiving Emergency Medical Services in King County. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14549. e2014549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao X, Zhang B, Li P, Ma C, Gu J, Hou P. MedrxivOrg; 2020. Incidence, clinical characteristics and prognostic factor of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis Running title: Predictors of clinical prognosis of COVID-19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo T, Shen Q, Guo W, He W, Li J, Zhang Y. Clinical Characteristics of Elderly Patients with COVID-19 in Hunan Province, China: A Multicenter, Retrospective Study. Gerontology. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1159/000508734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adorni F, Prinelli F, Bianchi F, Giacomelli A, Pagani G, Bernacchia D. JMIR Public Heal Surveill; 2020. Self-reported symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a non-hospitalized population: results from the large Italian web-based EPICOVID19 cross-sectional survey. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW. Presenting Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Outcomes among 5700 Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bao Y, Lin SY, Cheng ZH, Xia J, Sun YP, Zhao Q. Clinical Features of COVID-19 in a Young Man with Massive Cerebral Hemorrhage—Case Report. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2:703–709. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00315-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mizumoto K, Kagaya K, Zarebski A, Chowell G. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25:2020. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tay HS, Harwood R. Atypical presentation of COVID-19 in a frail older person. Age Ageing. 2020;49:523–524. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afaa068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grech V, Borg M. Influenza vaccination in the COVID-19 era. Early Hum Dev. 2020;148 doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gostin LO, Salmon DA. The Dual Epidemics of COVID-19 and Influenza: Vaccine Acceptance, Coverage, and Mandates. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.10802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sudre CH, Lee K, Ni Lochlainn M, Varsavsky T, Murray B, Graham MS. MedRxiv; 2020. Symptom clusters in Covid19: A potential clinical prediction tool from the COVID Symptom study app. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calderón-Larrañaga A, Vetrano DL, Onder G, Gimeno-Feliu LA, Coscollar-Santaliestra C, Carfí A. Assessing and Measuring Chronic Multimorbidity in the Older Population: A Proposal for Its Operationalization. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016:glw233. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. JAMA; 2020. Case-Fatality Rate and Characteristics of Patients Dying in Relation to COVID-19 in Italy. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, O'Halloran A, Cummings C, Holstein R. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 — Covid-net, 14 states, March 1–30, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458–464. doi: 10.15585/MMWR.MM6915E3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Characteristics of COVID-19 patients dying in Italy n.d. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/en/coronavirus/sars-cov-2-analysis-of-deaths (accessed June 10, 2020).

- 17.General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – Official Legal Text n.d. https://gdpr-info.eu/ (accessed October 7, 2020).

- 18.COVID-19 scheda Regioni n.d. https://github.com/pcm-dpc/COVID-19/blob/master/schede-riepilogative/regioni/dpc-covid19-ita-scheda-regioni-20200709.pdf (accessed July 9, 2020).

- 19.R Development Core Team (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org.n.d.

- 20.Bastiani L, Fortunato L, Pieroni S, Bianchi F, Adorni F, Prinelli F. MedRxiv; 2020. EPICOVID19: Psychometric assessment and validation of a short diagnostic scale for a rapid Covid-19 screening based on reported symptoms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellmann-Weiler R, Weiss G. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and therapy of infections in elderly patients - A mini-review. Gerontology. 2009;55:241–249. doi: 10.1159/000193996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keipp Talbot H, Falsey AR. The diagnosis of viral respiratory disease in older adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:747–751. doi: 10.1086/650486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam PP, Coleman BL, Green K, Powis J, Richardson D, Katz K. Predictors of influenza among older adults in the emergency department. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1966-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janssens JP, Krause KH. Pneumonia in the very old. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:112–124. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00931-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downton JH, Andrews K, Puxty JAH. Silent” pyrexia in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1987;16:41–44. doi: 10.1093/ageing/16.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuno O, Kataoka H, Takenaka R, Okubo F, Okamoto K, Masutomo K. Influence of age on symptoms and laboratory findings at presentation in patients with influenza-associated pneumonia. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:322–325. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babcock HM, Merz LR, Dubberke ER, Fraser VJ. Case-Control Study of Clinical Features of Influenza in Hospitalized Patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:921–926. doi: 10.1086/590663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuzil KM, O'Connor TZ, Gorse GJ, Nichol KL. Recognizing influenza in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who have received influenza vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:169–174. doi: 10.1086/345668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L. Self-reported Olfactory and Taste Disorders in Patients With Severe Acute Respiratory Coronavirus 2 Infection: A Cross-sectional Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:889–890. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attems J, Walker L, Jellinger KA. Olfaction and Aging: A Mini-Review. Gerontology. 2015;61:485–490. doi: 10.1159/000381619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schiffman SS. Taste and Smell Losses in Normal Aging and Disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 1997;278:1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160077042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ajmani GS, Suh HH, Pinto JM. Effects of ambient air pollution exposure on olfaction: A review. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1683–1693. doi: 10.1289/EHP136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ajmani GS, Suh HH, Wroblewski KE, Pinto JM. Smoking and olfactory dysfunction: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:1753–1761. doi: 10.1002/lary.26558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiffman SS. Influence of medications on taste and smell. World J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;4:84–91. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2018.02.005. Head Neck Surg. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.