Abstract

Background

There is evidence that physical fitness of children and adolescents (particularly cardiorespiratory endurance) has declined globally over the past decades. Ever since the first reports on negative trends in physical fitness, efforts have been undertaken by for instance the World Health Organization (WHO) to promote physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents. Therefore, it is timely to re-analyze the literature to examine whether previous reports on secular declines in physical fitness are still detectable or whether they need to be updated.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review is to provide an ‘update’ on secular trends in selected components of physical fitness (i.e., cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, speed) in children and adolescents aged 6–18 years.

Data Sources

A systematic computerized literature search was conducted in the electronic databases PubMed and Web of Science to locate studies that explicitly reported secular trends in physical fitness of children and adolescents.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included in this systematic review if they examined secular trends between at least two time points across a minimum of 5 years. In addition, they had to document secular trends in any measure of cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power or speed in apparently healthy children and adolescents aged 6–18 years.

Study Appraisal and Synthesis Methods

The included studies were coded for the following criteria: nation, physical fitness component (cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, speed), chronological age, sex (boys vs. girls), and year of assessment. Scores were standardized (i.e., converted to z scores) with sample-weighted means and standard deviations, pooled across sex and year of assessment within cells defined by study, test, and children’s age.

Results

The original search identified 524 hits. In the end, 22 studies met the inclusion criteria for review. The observation period was between 1972 and 2015. Fifteen of the 22 studies used tests for cardiorespiratory endurance, eight for relative muscle strength, eleven for proxies of muscle power, and eight for speed. Measures of cardiorespiratory endurance exhibited a large initial increase and an equally large subsequent decrease, but the decrease appears to have reached a floor for all children between 2010 and 2015. Measures of relative muscle strength showed a general trend towards a small increase. Measures of proxies of muscle power indicated an overall small negative quadratic trend. For measures of speed, a small-to-medium increase was observed in recent years.

Limitations

Biological maturity was not considered in the analysis because biological maturity was not reported in most included studies.

Conclusions

Negative secular trends were particularly found for cardiorespiratory endurance between 1986 and 2010–12, irrespective of sex. Relative muscle strength and speed showed small increases while proxies of muscle power declined. Although the negative trend in cardiorespiratory endurance appears to have reached a floor in recent years, because of its association with markers of health, we recommend further initiatives in PA and fitness promotion for children and adolescents. More specifically, public health efforts should focus on exercise that increases cardiorespiratory endurance to prevent adverse health effects (i.e., overweight and obesity) and muscle strength to lay a foundation for motor skill learning.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40279-020-01373-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| This systematic review documents a large initial increase and an equally large subsequent decrease for cardiorespiratory endurance, but the decrease appears to have reached a floor for all children between 2010 and 2015. Relative muscle strength showed a small increase. Proxies of muscle power indicated an overall small negative quadratic trend. Speed showed small-to-medium increases in recent years. |

| Because of the different trends in physical fitness, we recommend that already existing programs with the goal to promote PA and fitness should be maintained. More specifically, public health efforts should focus on exercise that increases cardiorespiratory endurance to prevent adverse health effects (overweight, obesity) and muscle strength to lay a foundation for motor skill learning. |

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (PA) daily and additionally muscle and bone strengthening activities three times per week for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years [1]. Recently published studies showed that a majority of children and adolescents (~ 80%) around the globe do not meet the recommended level of 60 min PA per day [2–4]. Children and adolescents who do not adhere to WHO recommendations [1], they are supposed to suffer from ‘exercise deficit disorder’ including all negative health consequences [5].

Childhood is an important developmental stage to acquire fundamental movement skills through daily PA in order to obtain motor skill competence and movement confidence. Children who do not gain such competencies due to sedentariness are more likely to experience adverse health outcomes later in life [5]. Furthermore, it has been postulated that a physically active lifestyle during childhood and adolescence is robust and tracks into adulthood [6–9]. For instance, Telama et al. [9] conducted a 27-year follow-up measurement of 3,596 Finnish boys and girls aged 3–18 years and reported that PA behavior develops during childhood and tracks into adulthood with moderate-to-high stability (stability coefficients ≥ 0.60).

There is evidence from cross-sectional [10] and longitudinal studies [11] of an association between levels of PA and physical fitness. According to Caspersen et al. [12], physical fitness can be categorized into health- (e.g., cardiorespiratory endurance, muscle strength, etc.) and skill-related (e.g., speed, power, etc.) components of physical fitness. Wrotniak et al. [10] used accelerometers to objectively measure PA and observed that time in moderate-to-vigorous PA positively correlated with measures of muscular strength (standing broad jump; r = 0.40) and speed (running speed; r = − 0.36) in children aged 8–10 years. These results were confirmed in a 3-year longitudinal study in which positive associations were reported between time spent in moderate-to-vigorous PA measured through accelerometers and different components of physical fitness [i.e., muscle strength (handgrip, β = 0.06)], proxies of muscle power (vertical jump, β = 0.04) in children aged 6–12 years [11].

Evidence-based research indicates that physical fitness is a powerful marker of health in children and adolescents [6]. In particular, cardiorespiratory endurance [13] and muscle strength [8] have been found to be positively associated with markers of health in children and adolescents. In a systematic review, Mintjens et al. [13] reported that performance levels in cardiorespiratory endurance were positively related with body mass index, waist circumference, body fatness, and prevalence of metabolic syndrome. Furthermore, Garzia-Hermoso et al. [8] reported positive associations between measures of muscle strength and body mass index, skinfold thickness, insulin resistance, triglycerides, cardiovascular disease risk score, and bone mineral density. Testing of physical fitness is easy-to-administer, reliable and valid which is why it should be extensively implemented to receive information on performance development and health of children and adolescents [14].

There is already evidence available in the literature on secular declines in physical fitness of children and adolescents. Tomkinson et al. [15, 16] summarized the existing literature on this topic for the timespan between 1958 and 2003. They included physical fitness data for 25,000,000–50,000,000 children and adolescents aged 6–19 years living in 27 countries across five geographical regions. Over the entire analysis period (1958–2003), cardiorespiratory endurance declined by − 0.36% per annum (p.a.). A more in-depth analysis indicated that between 1958 and 1970, cardiorespiratory endurance improved by + 0.61% p.a. Thereafter, performance declined by − 0.54% p.a. Findings for proxies of muscle power and speed were different in as much as there was an overall positive trend for both qualities (proxies of muscle power: + 0.03% p.a.; speed + 0.04% p.a.) between 1958 and 2003. When looking at the period from 1958 to 1985, improvements were found for proxies of muscle power (+ 0.44% p.a.) and speed (+ 0.27% p.a.). These were followed by annual declines in proxies of muscle power (− 0.20% p.a.) and speed (− 0.08% p.a.). Recently, Tomkinson et al. [17] published an update on secular trends in cardiorespiratory endurance restricting the analysis to data on the 20-m shuttle run test that were published between 1981 and 2014. In their meta-analysis, Tomkinson et al. [17] summarized data for almost 1,000,000 children and adolescents aged 9–17 years living in 19 different countries. According to their results, the international rate of cardiorespiratory endurance decline has slowed and stabilized since the turn of the century [17]. Furthermore, a recently published systematic analysis of secular trends on handgrip strength including data for 2,000,000 children and adolescents aged 9–17 years living in 19 countries showed that the international rate of improvement in handgrip strength progressively increased between 1967 and 2017 [18].

In summary, there is evidence that physical fitness of children and adolescents (particularly cardiorespiratory endurance) has declined globally, particularly in western industrialized countries until the turn of the century and stabilized ever since. These trend analyses in physical fitness were the starting point to specifically promote PA and physical fitness in children and adolescents, especially by the WHO [19].

Given the effort of the WHO over the past years to promote PA and physical fitness in children and adolescents [19], it appears important to regularly update these secular trend analyses. Considering that those updates are available only for cardiorespiratory endurance using estimated O2peak from the 20-m shuttle run test [17] and absolute muscle strength data from handgrip dynamometry [18], it is timely to re-analyze the literature and examine secular trends for other components of physical fitness such as relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and speed. It is also important to broaden the perspective on cardiorespiratory endurance, i.e., to include also tests other than the 20-m shuttle run test in the analyses.

The aim of this systematic review was to provide an ‘update’ on secular trends in selected components of physical fitness (i.e., cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, speed) in children and adolescents aged 6–18 years. With reference to recent studies [17, 18] and due to ongoing public health efforts to promote PA and fitness [19], we hypothesized a positive trend in physical fitness development of children and adolescents over time. We additionally expected that the reported secular trends are heterogeneous both in direction and magnitude and specific to the respective physical fitness component under consideration. This could be due to a multitude of tests that were used to assess the different components of physical fitness.

Methods

This systematic review was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines [20, 21].

Literature Search

The authors conducted a systematic computerized literature search in the electronic databases PubMed and Web of Science to locate studies that explicitly reported secular trends in physical fitness of apparently healthy children and adolescents. The literature search period covered publications until April 2019. An updated search in July 2020 could not identify any additional hits. The following Boolean search strategy was used to identify studies related to secular trends in physical fitness of children and adolescents. Proximity operators (“*”) were applied to search for root words: ("physical fitness" OR “cardiorespiratory endurance” OR “muscular endurance” OR “muscular strength” OR “body composition” OR flexibility OR agility OR balance OR coordination OR speed OR power OR “reaction time”) AND (child OR children OR youth OR adolescent OR adolescents OR adolescence) AND ("secular change*" OR "secular trend*" OR "secular decline*" OR "temporal trend*" OR "temporal change*" OR "temporal decline*").

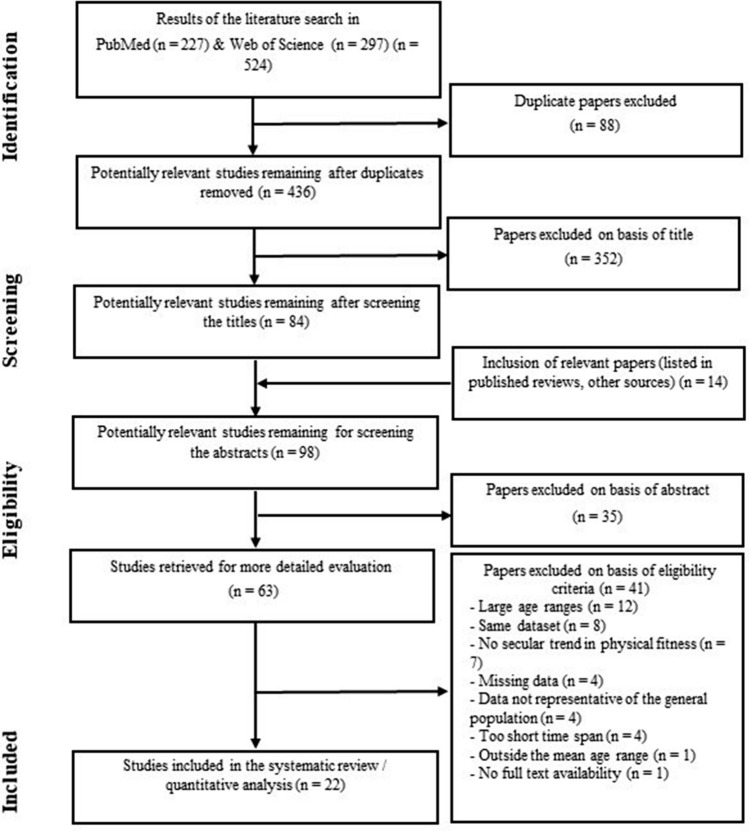

In addition, the following filters were activated for PubMed: species: humans; ages: birth–18 years (children), 13–18 years (adolescents). The applied search syntax for PubMed was adapted for the Web of Science database so that the abbreviation “TS = ” (for Topic) was placed in front of each bracket. Furthermore, reference lists of each article as well as relevant review articles and meta-analyses [15, 16, 22–31] were cross-referenced/screened to identify suitable adequate references to be included in this systematic review (see flow chart Fig. 1). We additionally scrutinized the database ‘Cochrane Library’, but could not identify any additional hits.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart illustrating the search and selection process of this systematic review

Selection Criteria

Studies were integrated in this systematic review if they provided relevant information with regards to a modified PICOS approach [21]. The considered parameters were population, outcomes, and study design. The following predefined inclusion criteria were selected: (1) population: apparently healthy children and adolescents with a mean age of 6–18 years; differentiated age ranges not spanning more than 3 years (e.g., 12- to 14-year olds) according to Tomkinson et al. [32]; a sample distinguished by sex allowing sex-specific analysis as recommended by Tomkinson [16]; (2) intervention: not possible; (3) comparator: not possible; (4) outcomes: secular trends in selected physical fitness components (i.e., cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, speed) expressed as mean, standard deviation/standard error, and sample size according to these studies [15, 16, 23]; (5) study design: in accordance with Jürimäe et al. [33], studies which spanned at least two time points across a minimum of 5 years; only published articles/datasets with full-text availability; articles published in English or German. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) population: patients or outside the mean age range of 6 to 18 years; large age ranges spanning more than 3 years (e.g., 12- to 15-year olds) [32]; children with an elite athletic background; children who live in specific areas (e.g., rural areas, Inuit) since their data are typically not representative of the general population [22]; a sample not distinguished by sex as recommended by Tomkinson [16]; (2) intervention: not possible; (3) comparator: not possible; (4) outcomes: assessment of secular trends not related to physical fitness; authors reported only aggregated physical fitness scores; missing data concerning means, standard deviation / standard error or sample size; (5) study design: samples which did not span at least two time points across a minimum of 5 years [33]; no full-text availability; articles published in languages other than English or German; data that were reported in several publications [32].

Two independent reviewers (TF, FA) screened potentially relevant papers by analyzing titles, abstracts, and full texts to determine study eligibility. If TF and FA did not reach agreement, UG was consulted for clarification.

Coding of Studies

All included studies were coded for the following variables listed in Table 1. The author TF extracted the relevant data in an Excel spreadsheet from all included studies.

Table 1.

Study coding

| Nation | Australia, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, England, Finland, Belgium (Flanders), Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, USA |

| Physical fitness components | Cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, speed |

| Chronological age | 6–18 years |

| Sex | Boys and girls |

| Trends | Positive, negative, stagnation |

If studies included several tests of the same physical fitness component, only one test was used according to the following ranking (Table 2). The list was created through expert rating based on the factors ‘practical relevance’ and ‘frequency of usage’ of the respective test.

Table 2.

Classification of the ranked physical fitness tests used in the included studies

| Cardiorespiratory endurance | Relative muscle strength | Proxies of muscle power | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-min rune | Leg lift teste | Standing broad jumpe | 20-m sprinte |

| 9-min rune | Sit-upa,e | Sargent jump and reach teste | 30-m sprinte |

| 20-m shuttle rune | Push-upb,e | 40-m sprinte | |

| Cooper test (12 min)e | Bent arm hange | 45,7-m (50-yd) sprinte | |

| 1200-m rune | Pull-upc,e | 50-m sprinte | |

| 1600-m rune | Arm-pull | 4 × 9-m shuttle run | |

| Maximal cycle ergometere | Bench-pressd | 10 × 5-m shuttle rune | |

| PWC 170 cycle ergometere | Two-hand lift | ||

| Submaximal cycle ergometere |

aMaximum repetition; number at a rate of 25 lifts per minute or counts/30 s

bCounts/40 s

cMaximum repetition

dNumber at a rate of 25 lifts per minute

eTests were included in analyses

If relevant data (e.g., means) were only reported in figures or graphs, the program GetData-Graph-Digitizer (https://www.getdata-graph-digitizer.com/index.php) was used for data extraction purposes.

Statistical Analyses

Computation of z scores for Components of Physical Fitness

Physical fitness was assessed through the fitness components cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and speed. For measures of relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and cardiorespiratory endurance, high scores indicate good and for measures of speed high scores indicate poor physical fitness. To facilitate readability, speed outcomes were multiplied by − 1. Thus, performance improvements over time were positive for all included outcome measures. The total sample size was calculated from the maximal sample sizes at age–time points–sex level for each included study.

As a common metric for tests, we converted means to z scores based on sample-weighted means and standard deviations for cells defined by study, test, and age of children. Specifically, means and standard deviations were pooled across sex and year within these cells. For three studies, standard deviations were computed from standard errors [34–36]; for two studies, the number of participants for subgroups was extrapolated from aggregate numbers [37, 38]. Of note, Spengler et al. [39] provided means and standard deviations for their study in response to a personal request. For pre- and post-processing of results, custom R code and (mainly) the following R packages were used: tidyverse [40], remef [41], sjPlot [42], cowplot [43], and broom.mixed [44].

Statistical Inference with an Integrated Linear Mixed Model

We specified a linear mixed model (LMM) to estimate effects of sex and linear, quadratic, and cubic secular trends as nested under the four components of physical fitness (i.e., 8 × 4 = 32 fixed effects). For each observation, year of assessment was centred at 1990, i.e., at the midpoint of first-year assessments between 1974 and 2006 across studies. The nested model specification implies that for each of the four fitness components, we obtained an estimate for the year 1990 (i.e., equivalent to an intercept), an estimate for the main effect of sex, estimates for the secular trend (three parameters for linear, quadratic, and cubic component), and estimates for the interactions of sex and secular trend.

We tested the effects of sex and secular trends within each of the four physical fitness components because it was clear from the outset that the qualitative differences between the physical fitness components would yield trivial higher-order interactions. The limitation of the nested-model specification is that we did not obtain outcomes that report differences between these physical fitness components (e.g., sex × component or secular trend × component interactions). We considered separate LMMs for each physical fitness component. This approach, however, would not take dependencies between measures from different physical fitness components and between dependencies across years within studies into account. Moreover, the number of observations available for each LMM would substantially reduce statistical power for each of them.

The LMM was estimated with the lmer() function of the R-based lme4 package [45, 46]. Model selection involved the determination of a random-effect structure that is supported by the data using random-effect principal component analysis [47, 48]. The final model included study-related variance components for cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, sex, and linear yearly trends for cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, and proxies of muscle power. The specification of correlation parameters for these variance components led to overparameterized models or did not significantly contribute to the goodness of fit as assessed with likelihood ratio tests. With this random-effect structure, none of the high-order interactions between sex and quadratic or cubic secular trends were significant.1 Therefore, we removed these eight fixed effects from the LMM. The protocol of model selection is available as Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix S2.

The LMM treated the 22 studies as levels of a random factor; they contributed a total of 652 observations. The LMM estimated 24 fixed effects, six variance components, and the residual variance (i.e., a total of 31 model parameters). A |z| value > 2.0 (i.e., alpha of 5%) was used as a criterion for rejection of the null hypothesis.

In response to reviewer requests, we specified two additional LMMs. First, we included age of children (dichotomized at 12.5 years) as an additional factor and documented this analysis in Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix S1. The second request was to address possible geographical/cultural differences between studies from different countries. This analysis is also reported in Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix S1.

Results

Study Characteristics

A total of 524 potentially relevant studies were identified in the electronic databases PubMed and Web of Science. Fourteen articles were found through other sources such as reference lists of relevant reviews articles or meta-analyses. After screening for titles, abstracts, and full texts, 22 studies were finally eligible for inclusion in this systematic review article. Figure 1 illustrates the respective flow chart.

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Secular trends in physical fitness were analyzed for N = 96,522 children and adolescents aged 6–18 years living in 17 different countries mainly in high-income countries such as the US, Australia, and Europe. Sample sizes ranged between 41 and 2,153 participants. Sixteen of the 22 studies were carried out in Europe [34, 37–39, 49–60], two in Australia [35, 61], one in the US [36], one in Canada [62], one in New Zealand [63], and one in Brazil [64]. The time span varied from six to 35 years with a mean value of 20 years and a median of 21 years. Six studies reported data for several time points [34, 39, 49, 57, 58, 64].

Table 3.

Summary of the studies used in this systematic review

| References | Country | Time points Observational period in brackets (years) |

Sex | Age range (years) | Range of sample sizes | Physical fitness component | Test(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matton et al. [49] | Belgium (Flanders) | 1972a/1980b, 2005 (33a/25b) | M, F | 12–17c | 161–2,153 | Strength, speed | BAH, SHR10 × 5 |

| Westerstahl et al. [50] | Sweden | 1974, 1995 (21) | M, F | 16 | 185–230 | Strength, power, endurance | 9 min, THL, SJAR, SU, BP |

| Reiff et al. [36] | USA | 1975, 1985 (10) | M, F | 10–17c | 196–786 | Strength, power, speed | PU, SHR4 × 9, 45,7 m, SBJ |

| Mészáros et al. [51] | Hungary | 1975, 2000 (25) | M | 10–13c | 160–191 | Speed, endurance | 30 m, 1200 m |

| Krombholz [52] | Germany | 1977, 2000 (23) | M, F | 6–7c | 80–220 | Power | SBJ |

| Sedlak et al. [53] | Czech Republic | 1977, 2012 (35) | M, F | 6 | 133–178 | Power | SBJ |

| Sziva et al. [38] | Hungary | 1979, 2004 (25) | M | 7–11c | 152–158d | Endurance | 12 min |

| De Moraes Ferrari et al. [64] | Brazil | 1979, 1989, 1999, 2009 (30) | M, F | 10–11 | 43–184 | Endurance | SCE |

| Runhaar et al. [54] | Netherlands | 1980, 2006 (26) | M, F | 9–12c | 41–505 | Strength, power, speed | BAH, SHR10 × 5, LLT, AP, SJAR |

| Reed et al. [62] | Canada | 1981, 2004 (23) | M, F | 9–11c | 252–2,151d | Endurance | SHR 20 m |

| Dollmann et al. [61] | Australia | 1985, 1997 (12) | M, F | 10–11c | 277–499 | Power, speed, endurance | 1600 m, 50 m, SBJ |

| Hardy et al. [35] | Australia | 1985, 2015 (30) | M, F | 9–15c | 109–546 | Power | SBJ |

| Wedderkopp et al. [55] | Denmark | 1986, 1998 (12) | M, F | 9 | 279–670 | Endurance | MCE |

| McAnally et al. [63] | New Zealand | 1987, 2011 (24) | M, F | 15 | 157–436 | Endurance | SCE |

| Aaberge and Mamen [56] | Norway | 1988, 2001 (13) | M, F | 15 | 77–106 | Power, endurance | SCE, SJAR |

| Pampakas et al. [37] | Hungary | 1989, 2004 (15) | M | 7–10,5c | 136–147d | Endurance | 12 min |

| Venckunas et al. [57] | Lithuania | 1992, 2002, 2012 (20) | M, F | 11–18c | 58–598 | Strength, power, speed, endurance | SBJ, SHR10 × 5, BAH, SU, SHR 20 m |

| Costa et al. [34] | Portugal | 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 (15) | M, F | 10–11 | 229–262 | Strength, power, speed | SU, SBJ, 40 m |

| Sandercock et al. [58] | England | 1998, 2008, 2014 (16) | M, F | 10–11 | 150–158 | Endurance | SHR 20 m |

| Palomäki et al. [59] | Finland | 2003, 2010 (7) | M, F | 15–16 | 640–1,142 | Endurance | SHR 20 m |

| Albrecht et al. [60] | Germany | 2005, 2011 (6) | M, F | 11–13 | 352–466 | Strength, power, endurance | SBJ, PHU, PWC |

| Spengler et al. [39] | Germany | 2006–2015 (9) | M, F | 6–7 | 220–274 | Strength, speed, endurance | 6 min, PHU, 20 m |

Studies were sorted chronologically according to the first year of measurement. The table illustrates the country of origin, the time points (years), the observational period (years), sex, the respective age range of the participating children and adolescents, the range of sample sizes, and the test(s) for which secular trends were reported

M = male, F = female, BAH = bent arm hang, THL = two hand lift, SU = sit-up, BP = bench-press, PU = pull-up, PHU = push-up, LLT = leg lift test, AP = arm-pull, SBJ = standing broad jump, SJAR = Sargent Jump and Reach, 20 m = 20-m sprint, 30 m = 30-m sprint, 40 m = 40-m sprint, 45,7 m = 45,7-m (50-yd) sprint, 50 m = 50-m sprint, SHR4 × 9 = 4 × 9-m shuttle run, SHR10 × 5 = 10 × 5-m shuttle run, 6 min = 6-min run, 9 min = 9-min run, 12 min = 12-min run (Cooper test), 1200 m = 1200-m run, 1600 m = 1600-m run, SHR 20 m = 20-m shuttle run, PWC = PWC 170 cycle ergometer, SCE = submaximal cycle ergometer, MCE = maximal cycle ergometer

aFor male

bFor female

cData are available for each yearly age

dAuthors only reported the whole sample size

To assess secular trends in physical fitness, 15 out of 22 studies used tests for cardiorespiratory endurance [37–39, 50, 51, 55–64], 11 used tests for proxies of muscle power [34–36, 50, 52–54, 56, 57, 60, 61], eight for relative muscle strength [34, 36, 39, 49, 50, 54, 57, 60], and eight for speed [34, 36, 39, 49, 51, 54, 57, 61]. A total of 26 different physical fitness tests were found in the included studies (Table 2).

Studies which assessed cardiorespiratory endurance included submaximal [56, 60, 63, 64] or maximal [55] tests on a cycle ergometer, the 20-m shuttle run test [57–59, 62] or time-related (6-min run test [39], 9-min run test [50], Cooper test [37, 38]) as well as distance-related cardiorespiratory endurance tests (1200-m run test [51], 1600-m run test [61]). Studies which assessed relative muscle strength comprised five different lower/upper limbs strength tests as well as tests for the assessment of trunk muscle strength. Accordingly, tests included the leg lift test [54], sit-up test [34, 50, 57], push-up test [39, 60], bent arm hang test [49], and pull-up test [36]. Studies which assessed proxies of lower limbs muscle power included either the standing broad jump test [34–36, 52, 53, 57, 60, 61] or the Sargent jump and reach test [50, 54, 56]. Studies which assessed speed comprised either linear sprint tests over short distances such as the 20-m sprint test [39], 30-m sprint test [51], the 40-m sprint test [34], the 45-m sprint test [36], the 50-m sprint test [61] or short shuttle runs such as the 10 × 5-m shuttle run test [49, 54, 57] (Table 3).

Secular Trends and Effects of Sex for Components of Physical Fitness

The 24 fixed-effect LMM estimates relating to sex, secular trend, and their interactions for each of the four components are displayed in Table 4 along with standard error, z statistic, and p value. In general, we observed the expected higher scores for boys than girls in all panels with effects ranging between 0.094 (relative muscle strength; not significant with p < 0.07) and 0.44 (cardiorespiratory endurance, p < 0.001). Interpretation of polynomial trends, however, must start with the highest-order significant trend or its interaction with sex; lower-order trends and main effects are usually qualified by them. In the following, we report statistics for the critical terms (lifted from Table 4); statistics for all lower-order terms are reported in the table.

Table 4.

Fixed-effects estimates of linear mixed model

| Component | Fixed-effects estimates | Standard error | z values | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiorespiratory endurance | 0.32595 | 0.12234 | 2.66 | 0.008 |

| Sex | 0.44032 | 0.05348 | 8.23 | < 0.001 |

| Year (linear) | − 0.02419 | 0.01027 | − 2.36 | 0.018 |

| Year (quadratic) | − 0.00365 | 0.00084 | − 4.35 | < 0.001 |

| Year (cubic) | 0.00012 | 0.00003 | 3.94 | < 0.001 |

| Sex × year (linear) | − 0.00796 | 0.00243 | − 3.28 | 0.001 |

| Relative muscle strength | − 0.17252 | 0.07174 | − 2.40 | 0.016 |

| Sex | 0.09356 | 0.05087 | 1.84 | 0.066 |

| Year (linear) | 0.01095 | 0.00720 | 1.52 | 0.128 |

| Year (quadratic) | 0.00067 | 0.00033 | 2.069 | 0.039 |

| Year (cubic) | − 0.00004 | 0.00002 | − 2.14 | 0.032 |

| Sex × year (linear) | 0.00066 | 0.00184 | 0.36 | 0.721 |

| Proxies of muscle power | 0.09430 | 0.03376 | 2.79 | 0.005 |

| Sex | 0.36078 | 0.04894 | 7.37 | < 0.001 |

| Year (linear) | − 0.00093 | 0.00536 | − 0.17 | 0.863 |

| Year (quadratic) | − 0.00060 | 0.00030 | − 2.04 | 0.042 |

| Year (cubic) | 0.00001 | 0.00002 | 0.70 | 0.486 |

| Sex × year (linear) | 0.00474 | 0.00169 | 2.80 | 0.005 |

| Speed | 0.03498 | 0.03732 | 0.94 | 0.349 |

| Sex | 0.18428 | 0.05015 | 3.67 | < 0.001 |

| Year (linear) | − 0.01822 | 0.00372 | − 4.90 | < 0.001 |

| Year (quadratic) | − 0.00044 | 0.00021 | − 2.11 | 0.035 |

| Year (cubic) | 0.00006 | 0.00001 | 4.60 | < 0.001 |

| Sex × year (linear) | 0.00277 | 0.00180 | 1.54 | 0.125 |

The coefficients define the functions that generate the secular trends shown in Fig. 2a. Significant effects are in bold

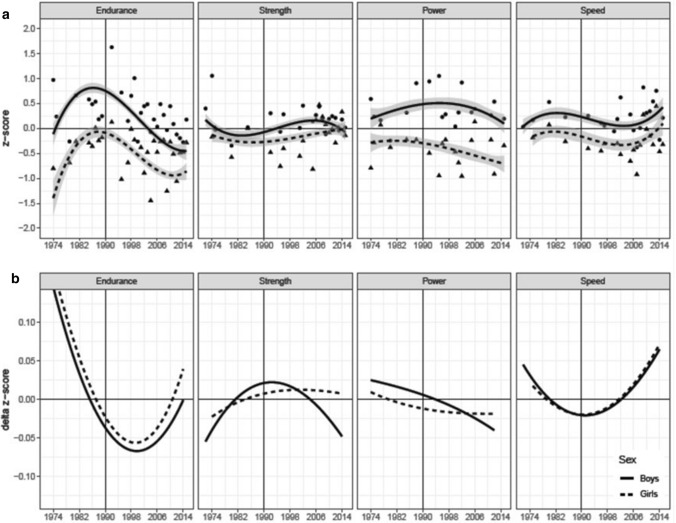

Data and model parameters (up to the highest-order significant term) were used to generate the partial-effect functions for secular trends shown in Fig. 2a. Partial effects no longer contain effects due to differences between studies in cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, sex, or due to linear yearly trends for cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, and proxies of muscle power. Points in the figure represent the observed sex × year means that result from averaging z scores across observations within age × study/test cells. Note that corresponding means predicted by data and model parameters (i.e., the values underlying the function fit) would be closer to the function due to LMM shrinkage (i.e., adjustments for variability, number of observations, and deviation from the Grand Mean). Nevertheless, observed means are also in good correspondence with partial-effect Z functions.

Fig. 2.

a Secular trends for cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and speed for standardized scores. Positive scores indicate better physical fitness in units of the standard normal distribution (z scores) relative to a grand mean of zero estimated for the year 1990. Dots represent the observed study means; the line is a third-order polynomial regression based on partial effects predicted from data and linear mixed model parameters (see Table 4); shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals for the regression lines. b Numeric approximations of first derivatives (delta z score) of corresponding functions in panel a (i.e., local changes in the direction of the function). Minima and maxima in panel a correspond to zero-crossings in b; inflection points in cubic functions in panel a correspond to minima and maxima of first derivatives in b

Minima, maxima, and—for cubic Z functions—inflection points provide critical information about secular trends. The years at which they occur are directly visible in the first derivative delta z score of such function. They were computed with a numeric approximation depicting the instantaneous rate of change (see Fig. 2b). Specifically, minima and maxima of the z score function in a-panels are at the years at which the delta z score function in b panels crosses the horizontal zero-line; inflection points of cubic z score functions are at years with minima and maxima of delta z score functions.2 With these advanced organizers, we turn to the component-specific secular trends and how they differ for boys and girls.

Cardiorespiratory Endurance

The LMM included 168 observations for cardiorespiratory endurance. The critical source of variance is the positive cubic trend (b = 0.00012, z = 3.94, p < 0.001; see Fig. 2a, cardiorespiratory endurance panel). Children’s cardiorespiratory endurance increased until 1986 and then decreased until around 2010–2012 with a negative inflection point in 2000. Since 2010, cardiorespiratory endurance may have stabilized or even tended to improve again (see zero-crossings and minimum in cardiorespiratory endurance panel Fig. 2b for identification of years). The interaction between sex and the linear trend for years is the source for a tendency towards smaller differences between boys’ and girls’ cardiorespiratory fitness or a steeper decline for boys than girls (b = − 0.00796, z = − 3.28, p = 0.001).

In terms of effect magnitude (i.e., the difference between maximum and minimum z scores across years), cardiorespiratory endurance exhibited very large secular trends with a range of about 1.5 standard deviations for both boys and girls. These effects are by far the largest of the four fitness components.

Relative Muscle Strength

The LMM included 156 observations for relative muscle strength. The critical source of variance is the cubic secular trend for all children (see Fig. 2a, relative muscle strength panel); b = − 0.00004, z = − 2.14, p = 0.032. There are no significant effects associated with sex, but the trend is clearer for boys. An initial decline with a local minimum in 1982 is followed by an increase to a local maximum in 2006 with a positive inflection point in 1990. The magnitude of the secular trend is small; scores move consistently within a narrow 0.50 z difference band.

Proxies of Muscle Power

The LMM included 164 observations for proxies of muscle power. The interaction between sex and the linear trend across years translates into shifting a very shallow negative quadratic curve (b = − 0.0006, z = − 2.04, p = 0.042) to different peaks in 1982 for girls and 1994 for boys; b = 0.00474, z = 2.80, p = 0.005. With 0.5, the effects are in the small-to-medium range.

Speed

The LMM included 164 observations for speed. Boys and girls exhibit a similar shape of their secular speed function (see also the close to identical delta z score functions in the speed panel of Fig. 2b). The shape of the function is defined by a significant negative linear (b = − 0.01822, z = − 4.90, p < 0.001) and a significant positive cubic (b = 0.00006, z = 4.60, p < 0.001) trend. The first local peak was in 1980 (a very shallow one); the negative inflection point was in 1990; speed bottomed out in 2002 and has been rising since then. Effect sizes are about 0.50 for both groups.

Effect Sizes and Conditional Means

The four components of physical fitness varied qualitatively with respect to the shape of their associated secular trends and differed between boys and girls in cardiorespiratory endurance and proxies of muscle power. They also differed in effect sizes. Effect sizes were large for cardiorespiratory endurance (1.5 units of standard deviation) and small-to-medium (0.5 units of standard deviations) for the other three components. Importantly, the partial-effect functions are corrected for various sources of heterogeneity between studies as described in the following.

LMMs afford tests of heterogeneity of studies with estimates of variance components (VCs) as model parameters that account for differences between studies beyond the residual error variance. Specifically in the present data, there was no evidence for speed-related and proxies-of-muscle-power-related VCs, but there were significant VCs for cardiorespiratory endurance (0.36),3 relative muscle strength (0.13), sex (0.18), and three linear yearly trends associated with cardiorespiratory endurance (0.03), relative muscle strength (0.013), and proxies of muscle power (0.011); the residual standard deviation was 0.25. Thus, there was considerable heterogeneity between studies and it was largest for cardiorespiratory endurance.

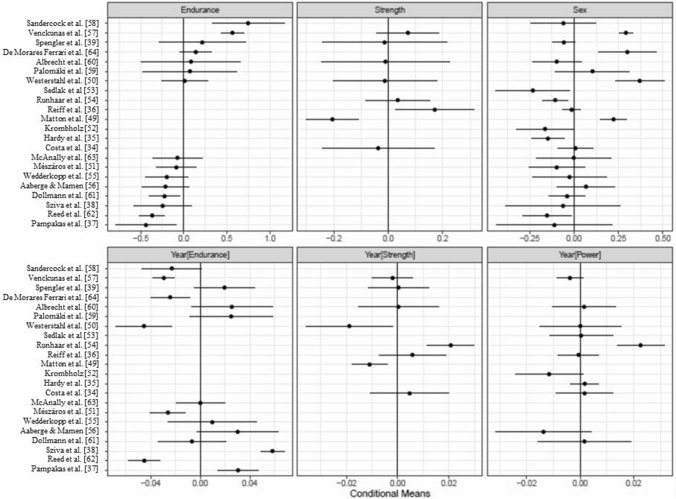

Data and model parameters can be used to generate predictions of conditional means at the level of studies for components of physical fitness with reliable inter-study differences. These predictions are shown in Fig. 3 along with intervals of ± 2 conditional standard deviations (~ 95% confidence intervals), based on the conditional variance–covariance matrices of the random effects returned by the ranef(model, condVar = TRUE) command of the lme4 R package [45].

Fig. 3.

Conditional means of six significant variance components in the linear mixed model

The conditional means differ from the observed means because they are shrunken towards the estimated population mean, conditional on (a) the distance of the observed from the grand mean, (b) the variance of the observed mean, and (c) the number of observations. Studies with confidence intervals completely to the left or the right of the vertical zero line (representing the grand mean), contributed significantly to heterogeneity. The major determinants of the width of the confidence intervals are the number of observations and their variance. For example, Veckunas et al. [57] contributed 48 and Sandercock et al. [58] four observations to the cardiorespiratory endurance component, accounting for the large difference between their respective intervals. Studies without an entry in a panel did not contribute observations to these components or their conditional mean was shrunk to the population mean. Taking into account this between-study heterogeneity was critical for the shape of the partial-effects functions in Fig. 2a.

Observation-Level Model Residuals

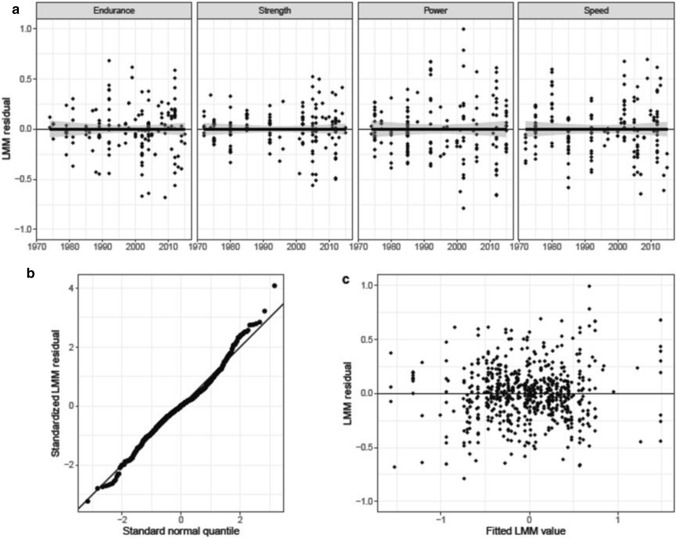

The quality of a model fit depends on distributional characteristics of the observation-level model residuals, most importantly that they are normally distributed and homoscedastic across the range of fitted values. Figure 4 displays a few diagnostic statistics (a: LMM residuals over year by component; b: standardized LMM residuals over theoretical quantiles of the standard normal distribution; c: LMM residuals over fitted values).

Fig. 4.

Observation-level residuals of linear mixed model (LMM). a LMM residuals over year by physical fitness component; b standardized LMM residuals over theoretical quantiles of the standard normal distribution; c LMM residuals over fitted values

The plots provide no evidence for violations of model assumptions. Somewhat surprisingly, there was no need for dealing with outliers. We interpret this as support for the quality of data selection, effectiveness of controlling for study heterogeneity as well as the selection of tests and their assignment to the four components of physical fitness.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to provide an update on secular trends in selected components of physical fitness of children and adolescents aged 6–18 years. The main findings of this systematic review including 22 studies and 652 observations were (a) a large initial increase and an equally large subsequent decrease between 1986 and 2010–12 in cardiorespiratory endurance; the decrease appears to have reached a floor for all children between 2010 and 2015, but it was steeper for boys than girls, (b) a general trend towards a small increase in relative muscle strength, (c) an overall small negative quadratic trend for proxies of muscle power; and (d) a small-to-medium increase in speed since 2002.

Secular Trends and Effects of Sex for Components of Physical Fitness

In this systematic review, we provide new information on secular trends in physical fitness of children and adolescents (i.e., cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and speed). There is evidence that cardiorespiratory endurance particularly declined between 1986 and 2010–12. Of note, it seems that the decline diminished during recent years for boys and girls. This finding confirms a recently published update by Tomkinson et al. [17] for cardiorespiratory endurance which showed that the international rate in cardiorespiratory endurance decline has slowed, but stabilized since the turn of the century for both boys and girls. Furthermore, Tomkinson et al. [17] reported that declines in cardiorespiratory endurance were larger for boys compared to girls which is also in line with our results.

These corresponding findings between our systematic review and the analysis of Tomkinson et al. [17] emphasize that the two reviews complement each other despite their different methodological approaches. While Tomkinson et al. [17] focused on the 20-m shuttle run, we additionally included data for time- and distance-related cardiorespiratory endurance tests. Tomkinson et al. [17] used the performance data from the 20-m shuttle run test and the equation provided by Léger and colleagues [65] to estimate O2peak from 20-m shuttle run performance for children and adolescents aged 8–19 years, irrespective of sex. In contrast, we used z scores as a common metric for all included tests.

Tomkinson and Olds [15] outlined that secular trends in physical fitness are affected by several aspects such as changed social, behavioral, physical, psychosocial, and physiological factors. In particular, psychosocial factors such as motivation, one’s willingness to push to maximally, and pacing strategies may have played a role, but unfortunately cannot be controlled. There are several reasons why especially fat mass and BMI may influence cardiorespiratory fitness. First, two studies reported that 40% [66]–70% [67] of the changes in cardiorespiratory endurance can be explained by changes in BMI. Second, performance in weight-bearing activities such as running over longer distances, etc. is negatively influenced by a high fat mass [28]. Cureton et al. [68] showed that gains in weight/higher fat mass significantly increased the energy cost during running. Therefore, the O2max (expressed relative to body mass) has a lower asymptote. Third, trends in cardiorespiratory endurance (decline which was recently mitigated) coincide with international trends of overweight and obesity. The NCD Risk Factor Collaboration [69] reviewed an increasing prevalence in overweight and obesity in school-aged children worldwide between 1975 and 2016, but stated that the trend has recently flattened, albeit at a high level, especially in high-income countries.

Another factor that might affect cardiorespiratory endurance is the level of PA. Although evidence-based information about secular trends in PA is missing [70], a recently published study by Guthold et al. [4] stated that in 2016 about 80% of children and adolescents (girls: 84.7% and boys: 77.6%) worldwide did not meet the recommended 60 min at moderate-to-vigorous PA per day proposed by the WHO. However, compared with data for 2001, PA levels have been relatively stable in girls over the past 15 years (85.1%), and have slightly improved in boys (80.1%). Keeping in mind the causal interaction between PA and physical fitness [11], the low(er) levels of PA might lead to a diminished exercise stimulus and consequently to reduced cardiorespiratory endurance [66].

Our update provided information on secular trends in relative muscle strength indicating a general trend towards a small increase in fitness related to relative muscle strength. In this respect, our systematic review also complements a recently published analysis conducted by Dooley et al. [18] about secular trends in absolute muscle strength using handgrip data. They showed that the international rate of improvement in handgrip strength progressively increased between 1967 and 2017 in 2,000,000 children and adolescents aged 9–17 years living in 19 countries.

With respect to proxies of muscle power, our systematic review revealed a small negative quadratic trend and with respect to speed a small-to-medium increase in recent years. Here, we describe some differences from an earlier comprehensive review that analyzed similar measures of speed and proxies of muscle power. Tomkinson [16] summarized the existing literature on physical fitness of children and adolescents between 1958 and 2003. He included proxies of muscle power and speed data for 25,000,000 children and adolescents aged 6–19 years living in 27 countries across five geographical regions between 1958 and 2003. For proxies of muscle power, Tomkinson [16] reported a decline starting in 1985 and no evidence for differences between boys and girls. We observed a decline starting in 1995 after a previous increase for boys and a flattening for girls. According to the Tomkinson review [16], speed has flattened since about 1985 after a previous slight increase for boys and girls. In contrast, we observed an initial increase which changed to a decline at about 1982 until 2002 for boys and girls. We note that our effects are in the small-to-medium range and that we had fewer studies contributing to these two fitness components than for cardiorespiratory endurance. Tomkinson [16] considered a much larger data base including the grey literature, many more children and adolescents and many more countries. The differences may well be due to differences in methods and study design.

Compared to secular trends in cardiorespiratory endurance (1.5 SD for boys and for girls), smaller trends were observed for relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and speed (0.5–1.0 SD). The reason for the observed different effects might be the varying influence of fat mass/BMI on components of physical fitness. Tomkinson et al. [28] examined to what extent fat mass/BMI influences cardiorespiratory endurance, proxies of muscle power, and speed. Fat mass/BMI correlated stronger with cardiorespiratory endurance (1600 m run) than with a proxy of muscle power (standing broad jump) or speed (50-m sprint). The correlations were r = − 0.52 for cardiorespiratory endurance, r = − 0.20 for proxies of muscle power, and r = − 0.24 for speed [28]. Furthermore, Tomkinson et al. [28] stated that for fat-free mass, the effect is the opposite. The correlations between fat-free mass and proxies of muscle power (r = 0.59) and speed (r = 0.57) were stronger than for cardiorespiratory endurance (r = 0.21). Based on our findings and the available data, we cannot conclude whether it is a matter of fitness or fatness. When taking the work of Tomkinson et al. [28] into account, it seems that fatness plays a role particularly in cardiorespiratory endurance.

Overall Interpretation and Implications

Overall, this systematic review demonstrated that there is no generic secular trend across the different physical fitness components and years because of significant cubic secular trends in measures of cardiorespiratory endurance, relative muscle strength, proxies of muscle power, and speed. Therefore, physical fitness components must best be analyzed separately because the components showed different patterns of secular trends over time. We recommend to regular examination of secular trends according to the specific physical fitness components and the monitored time span to detect changes in physical fitness as early as possible. Schools offer a suitable setting for the assessment of physical fitness because they reach all children during their development, growth, and formation of habits.

Because of the different trends in physical fitness observed in this systematic review and the literature, we recommend further initiatives in PA and fitness promotion for children and adolescents. More specifically, public health efforts should focus on exercising cardiorespiratory endurance and muscle strength because cardiorespiratory endurance [13] and muscle strength [8] have been reported to be positively associated with markers of health (i.e., body mass index, waist circumference, body fatness, bone mass) in children and adolescents. In addition, sufficient levels of muscle strength are a prerequisite for motor skill learning [71].

In this context, schools have a responsibility for promoting a physically active lifestyle because this is the only setting that reaches all children regardless of their socioeconomic background [72]. Therefore, structural curricula such as active recess, active education or active transportation to school, etc. are reasonable factors to reduce sedentary behavior and promote PA [73, 74]. It is crucial that parents and families are also included in these efforts [59]. Furthermore, the role of physical education classes needs to be strengthened to enable enhanced PA and fitness levels [73–75]. Several studies verify the positive impact of resistance training [76–80] and endurance training [81, 82] on children’s physical fitness. Based on this research, muscle strengthening and aerobic exercises can be included in the curricula as several studies [83–85] indicated that well-structured and well-designed physical education lessons can have a positive impact on the physical fitness of children and adolescents. In addition, Faigenbaum and Bruno [86] stated that children and adolescents who are regularly engaged in PA (e.g., through physical education, etc.) were more eager to develop complex movements and sport skills (e.g., in a sport club or free play).

Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. First, biological maturity or anthropometric data (e.g., body mass or body height) were not considered in the analysis because this information was not available in most of the included studies. There is strong evidence that physical fitness is related to biological maturity as more mature children and adolescents outperform less mature children and adolescents in physical fitness [87]. Furthermore, studies [88, 89] indicated a trend towards earlier maturation (age of puberty onset) over the last few centuries which is accompanied by an increase in physical fitness which may have influenced and altered secular trends. Future studies of secular trends in physical fitness of children and adolescents should always report the biological maturity status if possible. Second, every included study used different study designs (tests, instruments, methods, environmental conditions, etc.) for measuring physical fitness which resulted in inter-study variance especially for cardiorespiratory endurance and relative muscle strength. To better evaluate secular trends in physical fitness, future studies are advised to use identical test procedures among representative samples of children and adolescents worldwide [90]. Third, secular trends were mainly reported for high-income countries such as the United States, Australia, and Europe. Future studies should also be conducted in middle- and low-income countries using simple, cheap, valid, and reliable physical fitness measures. Fourth, the included studies are usually not representative of the population of their countries. Future studies should collect country-specific representative data. Fifth, all included studies reported mean values of secular trends. However, trends in mean values might be systematically biased if there have been concurrent trends in skewness whereas median values will not be biased. Future studies should also relate to measures of centrality (e.g., medians), variability (e.g., standard deviations), and asymmetry (e.g., skewness). Sixth, we do not claim that our systematic review was exhaustive; grey literature, project reports or unpublished work were not considered. Finally, an assessment of risk of bias was not conducted. Accordingly, future studies should include risk of bias assessment in their analysis.

Conclusions

This systematic review documents a large initial increase and an equally large subsequent decrease for cardiorespiratory endurance starting in 1986 and lasting until 2010–12. The decrease appears to have reached a floor for all children between 2010 and 2015. Measures of relative muscle strength showed a general trend towards a small increase. Measures of proxies of muscle power indicated an overall small negative quadratic trend. For measures of speed, a small-to-medium increase was observed since 2002. Because of the different trends in physical fitness, we recommend further initiatives in PA and fitness promotion for children and adolescents. More specifically, public health efforts should focus on exercising cardiorespiratory endurance to prevent adverse health effects (i.e., overweight, obesity) and muscle strength to lay a foundation for motor skill learning. Furthermore, studies are needed that examine dose–response relations for muscle and bone strengthening exercises in children and adolescents.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation on this article.

Conflicts of interest/competing interests

Thea Fühner, Reinhold Kliegl, Fabian Arntz, Susi Kriemler, and Urs Granacher declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this systematic review.

Availability of data and material

The R script is available in Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix S2. Data from the included studies are available in the Electronic Supplementary Material Appendix S3. Furthermore, the R script and the data set from all included studies are available through the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/rs7x2/?view_only=090b2e63c23e4e719f766f6791ed1a89.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

TF, RK, SK, and UG: made substantial contributions to conception and design; TF and FA: contributed to data collection; RK and TF carried out data analysis; TF, RK, SK, and UG: interpreted the data; TF: wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors were involved in revising it critically for important intellectual content; all authors provided final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Fixed effects were not considered and not even inspected during selection of the random-effects structure supported by the data.

These relations derive from the power rule of differentiation; of relevance here are:

f(x) = x—> f’(x) = constant, f(x) = x2—> f’(x) = 2x, and f(x) = x3—> f’(x) = 3x2.

Values are variances expressed as standard deviations (i.e., the square-root of the estimated VC).

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalman M, Inchley J, Sigmundova D, Iannotti RJ, Tynjälä JA, Hamrik Z, et al. Secular trends in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in 32 countries from 2002 to 2010: a cross-national perspective. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(Suppl 2):37–40. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hallal PC, Andersen LB, Bull FC, Guthold R, Haskell W, Ekelund U. Global physical activity levels: surveillance progress, pitfalls, and prospects. Lancet. 2012;380:247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: a pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 1·6 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Exercise deficit disorder in youth: play now or pay later. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2012;11:196–200. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e31825da961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ, Sjöström M. Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes. 2008;32:1–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput JP, Janssen I, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:197–239. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García-Hermoso A, Ramírez-Campillo R, Izquierdo M. Is muscular fitness associated with future health benefits in children and adolescents? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Sports Med. 2019;49:1079–1094. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Telama R, Yang X, Leskinen E, Kankaanpää A, Hirvensalo M, Tammelin T, et al. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:955–962. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Dorn JM, Jones KE, Kondilis VA. The relationship between motor proficiency and physical activity in children. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1758–e1765. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen LR, Kristensen PL, Junge T, Rexen CT, Wedderkopp N. Motor Performance as predictor of physical activity in children: the CHAMPS Study-DK. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47:1849–1856. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100:126–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mintjens S, Menting MD, Daams JG, van Poppel MNM, Roseboom TJ, Gemke RJBJ. Cardiorespiratory fitness in childhood and adolescence affects future cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Sports Med. 2018;48:2577–2605. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0974-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pate RR. Health-related measures of children’s physical fitness. J Sch Health. 1991;61:231–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1991.tb06021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tomkinson GR, Olds TS. Secular changes in pediatric aerobic fitness test performance: the global picture. In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 46–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomkinson GR. Global changes in anaerobic fitness test performance of children and adolescents (1958–2003) Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2007;17:497–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomkinson GR, Lang JJ, Tremblay MS. Temporal trends in the cardiorespiratory fitness of children and adolescents representing 19 high-income and upper middle-income countries between 1981 and 2014. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:478–486. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dooley FL, Kaster T, Fitzgerald JS, Walch TJ, Annandale M, Ferrar K, et al. A systematic analysis of temporal trends in the handgrip strength of 2,216,320 children and adolescents between 1967 and 2017. Sports Med. 2020;50:1129–1144. doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.g001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–28. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eisenmann JC, Malina RM. Secular trend in peak oxygen consumption among United States youth in the 20th century. Am J Hum Biol. 2002;14:699–706. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macfarlane D, Tomkinson GR. Evolution and variability in fitness test performance of Asian children and adolescents. In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 143–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malina RM, Katzmarzyk PT. Physical activity and fitness in an international growth standard for preadolescent and adolescent children. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:295–313. doi: 10.1177/15648265060274S511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malina RM. Physical fitness of children and adolescents in the United States: status and secular change. In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 67–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shephard RJ. Fitness of Canadian children: range from traditional inuit to sedentary city dwellers, and assessment of secular changes. In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomkinson GR, Léger LA, Olds TS, Cazorla G. Secular trends in the performance of children and adolescents (1980–2000): an analysis of 55 studies of the 20m shuttle run test in 11 countries. Sports Med. 2003;33:285–300. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomkinson GR, Hamlin MJ, Olds TS. Secular changes in anaerobic test performance in Australasian children and adolescents. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2006;18:314–328. doi: 10.1123/pes.18.3.314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomkinson GR, Olds TS. Secular changes in aerobic fitness test performance of Australasian children and adolescents. In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 168–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, Kang SJ, Kim DY. Secular trends in the aerobic fitness test performance and body mass index of Korean children and adolescents (1968–2000) Int J Sports Med. 2007;28:314–320. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tomkinson GR, Macfarlane D, Noi S, Kim DY, Wang Z, Hong R. Temporal changes in long-distance running performance of Asian children between 1964 and 2009. Sports Med. 2012;42:267–279. doi: 10.2165/11599160-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, Borms J. Who are the eurofittest? In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 104–128. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jürimäe T, Volbekiene V, Jürimäe J, Tomkinson GR. Changes in eurofit test performance of Estonian and Lithuanian children and adolescents (1992–2002) In: Tomkinson GR, Olds TS, editors. Pediatric fitness: secular trends and geographic variability. Basel: Karger; 2007. pp. 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa AM, Costa MJ, Reis AA, Ferreira S, Martins J, Pereira A. Secular trends in anthropometrics and physical fitness of young Portuguese school-aged children. Acta Med Port. 2017;30:108–114. doi: 10.20344/amp.7712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardy LL, Merom D, Thomas M, Peralta L. 30-year changes in Australian children’s standing broad jump: 1985–2015. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21:1057–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reiff GG, Dixon WR, Jacoby D, Ye GX, Spain CG, Hunsicker PA. The president’s council on physical fitness and sports 1985: national school population fitness survey. Washington: President's Council on Physical Fitness and Sports; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pampakas P, Meszaros Z, Kiraly T, Szmodis MB, Szakaly Z, Zsidegh M, Meszaros J. Longitudinal differences and trends in body fat and running endurance in Hungarian primary schoolboys. Anthropol Anz. 2008;66:317–326. doi: 10.1127/aa/66/2008/317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sziva A, Mészáros Z, Kiss K, Mavroudes M, Ng N, Mészáros J. Longitudinal differences in running endurance and body mass index—a 25-year comparison. Acta Physiol Hung. 2009;96:359–368. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.96.2009.3.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spengler S, Rabel M, Kuritz AM, Mess F. Trends in motor performance of first graders: a comparison of cohorts from 2006 to 2015. Front Pediatr. 2017 doi: 10.3389/fped.2017.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan L, François R, et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J Open Source Softw. 2019;4:1686. doi: 10.21105/joss.01686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hohenstein S, Kliegl R. remef: remove partial effects. 2020. https://github.com/hohenstein/remef/. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

- 42.Lüdecke D. sjPlot: data visualization for statistics in social science. 2020. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sjPlot/. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

- 43.Wilke CO. Cowplot: streamlined plot theme and plot annotations for ‘ggplot2‘. 2019. https://www.cran.r-project.org/web/packages/cowplot/index.html. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

- 44.Bolker B, Robinson D. broom.mixed: tidying methods for mixed models. 2020. https://www.cran.r-project.org/web/packages/broom.mixed/index.html. Accessed 7 Aug 2020.

- 45.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2020. https://www.R-project.org/.

- 47.Bates D, Kliegl R, Vasishth S, Baayen H. Parsimonious mixed models. 2015. https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.04967.

- 48.Matuschek H, Kliegl R, Vasishth S, Baayen H, Bates D. Balancing type I error and power in linear mixed models. J Mem Lang. 2017;94:305–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matton L, Duvigneaud N, Wijndaele K, Philippaerts R, Duquet W, Beunen G, et al. Secular trends in anthropometric characteristics, physical fitness, physical activity, and biological maturation in Flemish adolescents between 1969 and 2005. Am J Hum Biol. 2007;19:345–357. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westerstahl M, Barnekow-Bergkvist M, Hedberg G, Jansson E. Secular trends in body dimensions and physical fitness among adolescents in Sweden from 1974 to 1995. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:128–137. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2003.10274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mészáros J, Mahmoud O, Szabo T. Secular trend and motor performance scores in Hungarian school-boys. Facta Univ Ser Phys Educ Sport. 1999;1:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krombholz H. Haben sich motorische Leistungen von 3- bis 7-jährigen Jungen und Mädchen im Zeitraum von 1973 bis 2001 verschlechtert? Z Sportpsychol. 2011;18:161–171. doi: 10.1026/1612-5010/a000060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sedlak P, Pařízková J, Daniš R, Dvořáková H, Vignerová J. Secular Changes of adiposity and motor development in Czech preschool children: lifestyle changes in fifty-five year retrospective study. Biomed Res Int. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/823841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Runhaar J, Collard DCM, Singh AS, Kemper HCG, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw M. Motor fitness in Dutch youth: differences over a 26-year period (1980–2006) J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13:323–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wedderkopp N, Froberg K, Hansen HS, Andersen LB. Secular trends in physical fitness and obesity in Danish 9-year-old girls and boys: Odense school child study and Danish substudy of the European youth heart study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2004;14:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2004.00365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aaberge K, Mamen A. A comparative study of fitness levels among norwegian youth in 1988 and 2001. Sports. 2019;7:1–11. doi: 10.3390/sports7020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venckunas T, Emeljanovas A, Mieziene B, Volbekiene V. Secular trends in physical fitness and body size in Lithuanian children and adolescents between 1992 and 2012. J Epidemiol Commun H. 2017;71:181–187. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-207307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sandercock GRH, Ogunleye A, Voss C. Six-year changes in body mass index and cardiorespiratory fitness of English schoolchildren from an affluent area. Int J Obes. 2015;39:1504–1507. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2015.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palomäki S, Heikinaro-Johansson P, Huotari P. Cardiorespiratory performance and physical activity in normal weight and overweight Finnish adolescents from 2003 to 2010. J Sports Sci. 2015;33:588–596. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2014.951874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albrecht C, Hanssen-Doose A, Bös K, Schlenker L, Schmidt S, Wagner M, et al. Motorische Leistungsfähigkeit von Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland: Eine 6-Jahres-Kohortenstudie im Rahmen der Motorik-Moduls (MoMo) Sportwissenschaft. 2016;46:294–304. doi: 10.1007/s12662-016-0421-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dollmann J, Olds T, Norton K, Stuart D. The Evolution of fitness and fatness in 10–11-year-old Australian schoolchildren: changes in distributional characteristics between 1985 and 1997. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1999;11:108–121. doi: 10.1123/pes.11.2.108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reed KE, Warburton DER, Whitney CL, McKay HA. Secular changes in shuttle-run performance: a 23-year retrospective comparison of 9- to 11-year-old children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2006;18:364–373. doi: 10.1123/pes.18.3.364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McAnally HM, Reeves LM, Sligo JL, Hancox RJ. Intergenerational changes in adolescents’ physical fitness and weight in New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2018;131:16–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Moraes Ferrari GL, Bracco MM, Rodrigues-Matsudo VK, Fisberg M. Cardiorespiratory fitness and nutritional status of schoolchildren: 30-year evolution. J Pediatr. 2013;89:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Léger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6:93–101. doi: 10.1080/02640418808729800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olds T, Dollmann J. Are changes in distance-run performance of Australian children between 1985 and 1997 explained by changes in fatness? Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2004;16:201–209. doi: 10.1123/pes.16.3.201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Albon HM, Hamlin MJ, Ross JJ. Secular trends and distributional changes in health and fitness performance variables of 10–14-year-old children in New Zealand between 1991 and 2003. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:263–269. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.047142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cureton KJ, Sparling PB, Evans BW, Johnson SM, Kong UD, Purvis JW. Effect of experimental alterations in excess weight on aerobic capacity and distance running performance. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1978;10:194–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration Worldwide trends in body-mass index, under-weight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ekelund U, Tomkinson G, Armstrong N. What proportion of youth are physically active? Measurement issues, levels and recent time trends. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:859–865. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Granacher U, Lesinski M, Busch D, Muehlbauer T, Prieske O, Puta C. Effects of resistance training in youth athletes on muscular fitness and athletic performance. A conceptual model for long-term athlete development. Front Physiol. 2016;164:1–14. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization . International charter of physical education, physical activity and sport; 2015. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meyer U, Schindler C, Zahner L, Ernst D, Hebestreit H, van Mechelen W, et al. Long-term effect of a school-based physical activity program (KISS) on fitness and adiposity in children: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kriemler S, Meyer U, Martin E, van Sluijs EMF, Andersen LB, Martin BW. Effect of school-based interventions on physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents: a review of reviews and systematic update. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:923–930. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Meyer U, Roth R, Zahner L, Gerber M, Puder JJ, Hebestreit H, Kriemler S. Contribution of physical education to overall physical activity. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:600–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Drenowatz C, Greier K. Resistance training in youth—benefits and characteristics. J Biomed. 2018;3:32–39. doi: 10.7150/jbm.25035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Faigenbaum AD, Myer GD. Pediatric resistance training: benefits, concerns, and program design considerations. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2010;9:161–168. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181de1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Myers AM, Beam NW, Fakhoury JD. Resistance training for children and adolescents. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:137–143. doi: 10.21037/tp.2017.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Faigenbaum AD, MacDonald JP. Dynapenia: it’s not just for grown-ups anymore. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106:696–697. doi: 10.1111/apa.13797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lesinski M, Herz M, Schmelcher A, Granacher U. Effects of resistance training on physical fitness in healthy children and adolescents: an umbrella review. Sports Med. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s40279-020-01327-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Armstrong N, Tomkinson G, Ekelund U. Aerobic fitness and its relationship to sport, exercise training and habitual physical activity during youth. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45:849–858. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Armstrong N. Aerobic fitness and training in children and adolescents. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2016;28:7–10. doi: 10.1123/pes.2016-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Granacher U, Muehlbauer T, Doerflinger B, Strohmeier R, Gollhofer A. Promoting strength and balance in adolescents during physical education: effects of a short-term resistance training. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25:940–949. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c7bb1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Faigenbaum AD, Bush JA, McLoone RP, Kreckel MC, Farrell A, Ratamess NA, Kang J. Benefits of strength and skill-based training during primary school physical education. J Strength Cond Res. 2015;29:1255–1262. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000000812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu Y, Burns RD, Constantino N, Fitzsimmons J, Zhang P. Effect of the resistance exercise on elementary school students’ physical fitness. SSEJ. 2019;17:468–475. doi: 10.1007/s42978-019-0022-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Faigenbaum AD, Bruno LE. A fundamental approach for treating pediatric dynapenia in kids. ACSMs Health Fit J. 2017;21:18–24. doi: 10.1249/FIT.0000000000000312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]