Abstract

Consumer uptake of direct-to-consumer (DTC) DNA ancestry testing is accelerating, yet few empirical studies have examined test impacts on recipients despite the DTC ancestry industry being two decades old. Participants in a longitudinal cohort study of response to health-related DTC genomic testing also received personal DNA ancestry testing at no additional cost. Baseline survey data from the primary study were analyzed together with responses to an additional follow-up survey focused on the response to ancestry results. Ancestry results were generated for 3466 individuals. Of those, 1317 accessed their results, and 322 individuals completed an ancestry response survey, in other words, approximately one in ten who received ancestry testing responded to the survey. Self-reported race/ethnicity was predictive of those most likely to view their results. While 46% of survey responders (N = 147) reported their ancestry results as surprising or unexpected, less than 1% (N = 3) were distressed by them. Importantly, however, 21% (N = 67) reported that their results reshaped their personal identity. Most (81%; N = 260) planned to share results with family, and 12% (N = 39) intended to share results with a healthcare provider. Many (61%; N = 196) reported test benefits (e.g., health insights), while 12% (N = 38) reported negative aspects (e.g., lack of utility). Over half (N = 162) reported being more likely to have other genetic tests in the future. DNA ancestry testing affected individuals with respect to personal identity, intentions to share genetic information with family and healthcare providers, and the likelihood to engage with other genetic tests in the future. These findings have implications for medical care and research, specifically, provider readiness to engage with genetic ancestry information.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s12687-020-00481-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Genetic ancestry, Direct-to-consumer testing, Personal genetic information, Ethnicity, Race

Introduction

Consumer uptake of direct-to-consumer (DTC) DNA ancestry testing has grown at an accelerating rate since these tests emerged on the market in the early 2000s. In 2018 alone, there were more DNA ancestry tests taken than in all previous years combined (Regalado, 2019), and there are reports that over 26 million people have participated in DTC DNA ancestry testing as of early 2019 (Regalado, 2019). DTC DNA ancestry testing is expected to rise in popularity (Regalado, 2019; Bowen & Khoury, 2018; Regalado, 2018) due to extensive commercial marketing and advertising (Regalado, 2019; Regalado, 2018; Marks, 2018; Roth & Lyon, 2018; Zhang, 2018; Garrison & Bardill, 2019), lowered testing kit costs (Regalado, 2019; Bowen & Khoury, 2018; Regalado, 2018; Roth & Lyon, 2018), stories of celebrity and political figures taking tests in the popular media (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Garrison & Bardill, 2019; Bolnick et al., 2007a; Garrison, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018), interest in genealogy and blood relations (Bowen & Khoury, 2018; Marks, 2018; Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Royal et al., 2010; Rodriguez, 2014; Haeusermann et al., 2017a; Kirkpatrick & Rashkin, 2017; Hesman, 2018), and interest in self-identity (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Zhang, 2018; Bolnick et al., 2007a; Garrison, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Rodriguez, 2014; Hirschman & Panther-Yates, 2008; DeFabio, 2016; Phillips, 2016; Dockser, 2018; Reich, 2018; Shim et al., 2018).

The impact of ancestry on healthcare decision-making, in general, has been discussed in the literature as ancestry can influence disease susceptibility (Bolnick et al., 2007a; Risch et al., 2002; Helgadottir et al., 2006; Bolnick, 2008; Tate & Goldstein, 2008). For example, BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutations are known to disproportionately impact Ashkenazi Jews leading to increased risk for breast, ovarian, and prostate cancer (Struewing et al., 1997). Knowing one’s background, specifically, having Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, can influence actionable healthcare decision-making with clinical utility such as ordering BRCA mutation testing (Francke et al., 2013). Relatedly, Ashkenazi Jews and French Canadians may opt to engage in carrier screening for Tay-Sachs Disease during family planning (National Institutes of Health, n.d.; Myerowitz & Hogikyan, 1986), and learning of African descent may prompt discussion of sickle cell anemia with one’s provider (National Institutes of Health, n.d.; Livingstone, 1958). For adoptees, especially, learning of one’s ancestry may inform medical care by allowing for more accurate reporting during family history taking (Su et al., 2011). Lastly, learning ancestry information is reportedly a top priority for DTC genetic test consumers (Roberts et al., 2017), especially to help confirm ancestry (Francke et al., 2013), and consumers may be interested in sharing ancestry testing results with healthcare providers (Bolnick et al., 2007a). Indeed, the healthcare community has been identified as an important stakeholder in ancestry testing (Royal et al., 2010).

Researchers, scholars, and journalists have previously written and speculated about the potential impact of DTC DNA ancestry test results on consumers (Bolnick et al., 2007a; Royal et al., 2010; Brown, 2018), including psychological distress (Zhang, 2018; Garrison, 2018; DeFabio, 2016; Haeusermann et al., 2017b); changes in health behaviors, perceived health risks, and health services engagement (Royal et al., 2010; Dockser, 2018; Reich, 2018; Smart et al., 2017); perceptions of identity (Zhang, 2018; Bolnick et al., 2007a; Garrison, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Royal et al., 2010; DeFabio, 2016; Foeman et al., 2015); and implications for deportation (Khandaker, 2018). Additionally, the perceived lack of oversight of DTC DNA ancestry testing by federal regulatory bodies (Wagner et al., 2012) has raised concerns about the use of these tests (Phillips, 2016; Smart et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2009; Ramos & Weissman, 2018). Despite DTC DNA ancestry testing being two decades old coupled with its rising popularity, empirical investigations of the effects of these tests on recipients are scant.

The few empirical studies that do exist, described below, are helpful for understanding cultural and identity-related impacts but lack exploration of health-related impacts of DNA ancestry testing. Indeed, the intersection of ancestry and healthcare is evolving as DNA ancestry testing companies are increasingly entering the U.S. healthcare space (Petrone, 2019; Ramsey, 2019; Ray, 2019; Rubin & Dockser, 2019).

A retrospective, online survey and phone interview study of 100 DTC DNA ancestry test takers conducted in 2009–2010 explored respondents’ racial and ethnic identities at two timepoints—an average of 4 years post-testing and then 18 months later, in order to examine how respondents made sense of their results (Roth & Ivemark, 2018). Most respondents (> 60%) did not change how they viewed their ethnic or racial identities post-testing even when results provided new identity information. White respondents, however, were more likely to incorporate other identities post-test in comparison with non-White respondents (Roth & Ivemark, 2018).

A retrospective, online survey study conducted in 2009–2011 examined the effect of DNA ancestry test results on ethnic and racial identities in 482 DNA ancestry test takers from around the world (Roth & Lyon, 2018). Motivations for taking the tests included interest in genealogy, receiving health information, and proving or disproving family stories that had been passed down (Roth & Lyon, 2018). Over half of the respondents reported that ancestry results affected their perception of their identity with 40% reporting a change in perceived race or ethnicity (Roth & Lyon, 2018). Approximately half of the respondents reported some change in their friendships and activities such as attending places of worship or engaging with new communities (Roth & Lyon, 2018). Test satisfaction often depended on how similar the results were to test recipients’ pre-test perceived ancestry or identity as well as openness to accepting discrepant results (Roth & Lyon, 2018), with greater consistency associated with higher satisfaction.

An exploratory interview study of 45 undergraduate students conducted in 2011–2012 looked at census identification pre- and post-ancestry DNA data (Foeman et al., 2015). Thirty-seven percent reported being surprised by their results, and one-third of the sample reportedly changed their U.S. Census identification after receiving results with White students being less likely to change their identification (Foeman et al., 2015). Most (88%) shared their results with family or friends (Foeman et al., 2015).

Taken together, data from these three studies suggest that test takers are impressionable to genetic ancestry test results. Despite race and ethnicity identities being intricate and multidimensional constructs (Nelson, 2008), they can be conflated with ancestry or confusingly perceived as being rooted in one’s DNA (Bolnick et al., 2007a; Walajahi et al., 2019). Furthermore, ancestry test results may be viewed as definitive (TallBear, 2013) and even given priority to lived personal experiences or other sociocultural identities (Elliott & Brodwin, 2002; Bader & Malhi, 2015), despite the limitations of testing due to finite reference samples with incomplete sampling that disproportionately represents some groups (Bolnick et al., 2007a; Royal et al., 2010; Rotimi, 2003) and results in estimation issues and inaccurate ancestry inferences (Royal et al., 2010; Bader & Malhi, 2015). All of this might explain why 33.3–40% of the study samples reported changes to their perceived race and ethnicity, even to the point of results changing participants’ census reporting (Bolnick et al., 2007a; Royal et al., 2010; Walajahi et al., 2019; Elliott & Brodwin, 2002). Indeed, scholars have previously drawn attention to some test takers changing how they report race or ethnicity on medical questionnaires, government forms, or college or job applications, or even feeling entitled to access affirmative action or Native American benefits (Bolnick et al., 2007a; Royal et al., 2010; Walajahi et al., 2019; Elliott & Brodwin, 2002).

Here, we present a large sample survey study with data on health-related impacts of DNA ancestry testing (i.e., results sharing with healthcare providers, attitudes towards future genetic testing). We use quantitative and qualitative approaches to assess the impacts of DNA ancestry testing on recipients’ test-related distress, cultural identity, and propensity for information sharing as well as the extent to which demographic factors were associated with participation in different stages of the DNA ancestry testing process.

This study of the impacts of ancestry testing was part of a larger study of the psychological and behavioral impacts of health-related DTC genomic testing (Bloss et al., 2011). This paper is the first, to our knowledge, to report on health-related impacts from engaging in genetic ancestry. These data are valuable given the limited empirical investigation of health-related impacts of personal DNA ancestry testing, as well as the dearth of empirical data examining impacts of personal DNA ancestry testing, broadly. Thus, this study might inform and spur future research on how and whether DTC DNA ancestry testing impacts health and healthcare among consumers.

Material and methods

Participants

Participants were individuals enrolled in the Scripps Genomic Health Initiative (SGHI), a longitudinal, U.S.-based cohort study launched in 2008 that examined the psychological and behavioral impacts of health-related DTC genomic testing (Bloss et al., 2011; Bloss et al., 2010). Survey data were collected in 2010. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Scripps Health and The Scripps Research Institute. Recruitment procedures have been published elsewhere (Bloss et al., 2011; Bloss et al., 2010). Informed consent was obtained electronically from each study participant.

Procedures

Prospective SGHI participants were told that they would receive both health-related genomic testing and DNA ancestry testing as part of the study. Participants were first provided with the Navigenics Health Compass genetic test, which was a commercially available DTC genomic test for complex disease risk. Study participants completed baseline and follow-up surveys (offered only in English) focused on assessing the psychological and behavioral impacts of this health-related genomic test.

At the time of study launch, Navigenics did not offer DNA ancestry testing, and, therefore, an analysis pipeline and interactive website (see Supplemental Figs. 1, 2, and 3) for return of DNA ancestry results were developed in-house by SGHI researchers. The methods for assessing ancestry via participants’ genotypes have been published elsewhere (Libiger & Schork, 2013). See Supplemental Table 1 for more detailed descriptions of the analytic strategies used. Return of these results and administration of a brief optional survey to assess the impact of the information provided was conducted separately from the return of health-related results and surveys.

Samples from SGHI participants who completed a baseline survey were processed for ancestry analysis. When ancestry test results were ready, participants were sent an email with an embedded link to access their results online. The interactive website provided a tutorial on how to interpret and understand the data and offered answers to “frequently asked questions.” After viewing DNA ancestry results, participants received a prompt to complete an optional survey that was focused on the impact of the information provided (see survey in Appendix).

Measures

Demographic items

As part of the baseline survey, participants were asked to provide answers to several demographic questions including self-reported race/ethnicity (stimulus: “what is your ethnicity?”; response options: “Caucasian,” “African-American,” “Hispanic/Latino,” “Asian,” “American Indian/Alaskan Native,” “Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander”) and sex (stimulus: “gender”; response options: “male” and “female”). Participants were limited to selecting one response option each. The wording of these items and the response options provided are somewhat restricted relative to present-day standards; however, the approach was similar to wording and response options used in demographic questions in other DTC genomic studies conducted during the same timeframe.

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

This 40-item, self-report measure assesses both state (i.e., temporary) and trait (i.e., longstanding personality characteristic) anxiety using a 4-point frequency scale and has consistently shown high internal reliability (McDowell, 2006). The STAI had high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93 and 0.94 for trait and state anxiety, respectively) in the current study.

Ancestry results impact survey

An 11-item survey was developed by the senior author (CB) to assess the impact of DNA ancestry test results (see Appendix) using a 3-point response scale. The design of the survey was informed by several relevant resources (Bolnick et al., 2007b; Nixon, 2007; The American Society of Human Genetics, 2008; Klimentidis et al., 2009; Via et al., 2009). Questions pertained to the following four overarching themes: general response to ancestry results (two items), cultural/personal identity (four items), sharing results (two items), and attitudes towards DNA ancestry testing (three items). The survey also included two open-ended questions that asked respondents: “[w]hat are the advantages to learning your estimated genetic ancestry?” and “[w] hat are the disadvantages to learning your estimated genetic ancestry?”

Discrepant results

We compared self-reported race/ethnicity at baseline and the overall ancestry category produced from genotypic ancestry testing (i.e., “genetically most similar to:”) to derive a variable indicating whether or not a participant’s DNA ancestry results were discrepant with their pre-testing self-reported race/ethnicity. There were six different self-reported race/ethnicity categories (outlined above) and eight overall ancestry categories (i.e., People from Europe, People from East Asia, People from Central Asia, African-American people, People from Sub-Saharan Africa, Indigenous people from America, People from Mexico, People from West Asia). All possible combinations of self-reported race/ethnicity and overall DNA ancestry were independently coded by three authors (CKR, RT, and CB) as either “discrepant” or “non-discrepant” (dichotomous categorization). Instances of coding disagreement between the first two authors (CKR and RT) were resolved using the senior author’s (CB) independent coding as a tie-breaker. “Non-discrepant” ancestry results occurred when self-reported race/ethnicity was consistent with DNA ancestry findings (e.g., self-report of “Caucasian” would be consistent with a genetic finding of “genetically most similar to people from Europe”), whereas discrepant results occurred when self-reported race/ethnicity was inconsistent with DNA ancestry findings (e.g., self-report of “African-American” with a genetic finding of “genetically most similar to people from West Asia”). These determinations were made by individual coders using their best discretion, and multi-coder consensus coding was used to evaluate reliability. From this coding process, interrater reliability was 0.83. The dichotomous ancestry discrepancy variable was used in quantitative data analyses described below.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata/SE 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample.

Predictors of viewing ancestry results

Logistic regressions were used to determine the likelihood that a participant accessed their online DNA ancestry test results (0 = did not access DNA ancestry results, 1 = accessed DNA ancestry results) as well as the likelihood that a participant who accessed their results went on to complete the ancestry survey (0 = did not complete survey, 1 = completed survey). Eight independent variables (i.e., sex, age, self-reported race/ethnicity, Scripps Health employee status, household income, highest completed education, primary language other than English, and trait anxiety) were included in all logistic regressions. Age was modeled using both linear and quadratic terms as previous research suggests modeling age nonlinearly when using a sample with a large age range (Roberts, 1986; Mous et al., 2017) is appropriate; self-reported race/ethnicity categories were dichotomized into self-reported “Caucasian” and ascribed others (combined in order to have enough statistical power to run the analysis); household income and highest education were each binned and modeled as ordinal variables; and both primary languages other than English and Scripps Health employee status were dichotomized (1 = yes, 0 = no). Wald tests were used to determine the statistical significance of the associations.

Impacts of ancestry testing

Predictors of ancestry testing impacts

Ten independent variables (i.e., sex, age, self-reported ethnicity/race, Scripps Health employee, household income, highest education, primary language other than English, trait anxiety, discrepant ancestry results, and past ancestry testing) were included in linear regressions with the ancestry survey items as the outcome variables. Past ancestry testing was ordinal (i.e., 1 = yes, 0.5 = not sure, 0 = no). Fisher’s exact tests were used to assess potential associations between intention to share results with a healthcare provider (1 = yes; 0.5 = maybe; 0 = no) and self-reported race/ethnicity (0 = Caucasian;1 = other groups); overall ancestry (0 = genetically most similar to people from Europe; 1 = genetically most similar to people from other regions); and discrepant results (0 = non-discrepant; 1 = discrepant).

Perceived advantages and disadvantages

Qualitative data from the two open-ended questions (i.e., “[w]hat are the advantages to learning your estimated genetic ancestry?” and “[w]hat are the disadvantages to learning your estimated genetic ancestry?”) were analyzed using conventional content analytic methods (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Given the brevity of participant responses to these questions (18 average words per response for advantages; 5 average words per response for disadvantages) and our intent to use these data to provide context for a participant’s quantitative responses, inductive content analysis was used to provide a “condensed and broad description of the phenomenon” (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). Following content analysis, the corpus of data was reviewed several times prior to any attempt to synthesize the information. The data were then reviewed for key concepts, from which initial codes were derived. Using these initial codes, two authors (CT and CKR) then reviewed the corpus of data and added, changed, and/or combined codes as needed to best reflect themes in the data. Advantages and disadvantages of the ancestry test results were each dichotomized (1 = present, 0 = not present) to indicate whether a respondent had written a response and included in linear regressions to examine associations with the individual ancestry survey items as outcome variables.

Statistical significance was set at p < .05 for all of the abovementioned analyses, and all p values are uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Results

Sample characteristics

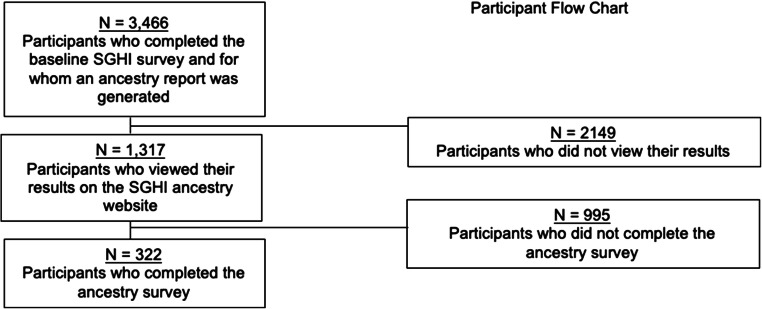

Of the 3466 SGHI participants for whom an ancestry report was generated and returned, 1317 (38.0%) accessed their DNA ancestry results. Of the 1317 participants who accessed results, 322 (24.4%) completed the ancestry results survey, in other words, approximately one in ten who received ancestry testing responded to the survey. Survey completers were mostly self-reported Caucasian (88.2%), highly educated (86.4% with at least a 4-year college degree), and of high socioeconomic status (49.6% with annual income over $150,000). Ancestry results were considered discrepant relative to baseline self-reported race/ethnicity for 5.3% of the entire sample (n = 185) and 4.0% for survey responders (n = 13). See Fig. 1 for a study participation flowchart and Table 1 for additional demographic characteristics of the 322 participants who completed the ancestry results survey. See Supplemental Tables 2 and 3 for frequencies of overall DNA ancestry findings and a breakdown of discrepant results, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Participant flowchart

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for demographic variables and covariates

| Variable | Completed ancestry survey (N = 322) |

|---|---|

| Sex (n, %) | |

| Male | 153, 47.5% |

| Female | 169, 52.5% |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean, SD | 46.91 ± 11.68 |

| Range | 22–81 |

| Income (n, %) | |

| Under $50,000 | 14, 4.3% |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 66, 20.5% |

| $100,000–$149,999 | 82, 25.5% |

| $150,000–$199,999 | 48, 14.9% |

| $200,000–$249,999 | 41, 12.7% |

| $250,000–$299,999 | 23, 7.1% |

| $300,000 or more | 48, 14.9% |

| Highest completed education (n, %) | |

| Less than high school (HS) | 3, 0.9% |

| HS/GED | 21, 6.5% |

| 2-year college | 20, 6.2% |

| 4-year college | 72, 22.4% |

| Some post-college | 54, 16.8% |

| Master’s degree | 88, 27.3% |

| Professional/Ph.D. | 64, 19.9% |

| Self-reported ethnicity/race (n, %) | |

| Caucasian | 284, 88.2% |

| Hispanic/Latino | 18, 5.6% |

| Asian | 13, 4.0% |

| African-American | 4, 1.2% |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 2, 0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 1, 0.3% |

| Scripps Health employee (n, %) | 52, 16.1% |

| Baseline State Anxiety (Mean, SD) | 35.51 ± 10.02 |

| Baseline Trait Anxiety (Mean, SD) | 33.73 ± 10.35 |

Predictors of viewing ancestry results

Supplemental Table 4 shows differences in survey completion by demographic characteristics.

Logging on to view DNA ancestry results

Self-reported race/ethnicity, age, Scripps Health employee status, and education were statistically significant predictors of accessing DNA ancestry results (see Table 2). Specifically, individuals who self-reported as “Caucasian” were more likely (40% accessed results; N = 1127) than other groups (among other groups 29% accessed results; N = 190) to access results as were individuals with higher completed education (among those with at least a 4-year college degree 40% accessed results; N = 1097). Scripps Health employees were less likely than non-Scripps Health employees to access results (30% accessed results; N = 221). Both linear and quadratic age terms were statistically significant (p ≤ .001), suggesting that the age effect on the likelihood to access results changed across all levels of age. Specifically, 18–19-year-olds had the highest predicted probability of accessing their DNA ancestry results (58.0%), while 57–58-year-olds had the lowest predicted probability (34.0%).

Table 2.

Breakdown of results for accessing online genetic ancestry results

| Accessing online genetic ancestry results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio | Wald test | p value |

| Ethnicity/race (i.e., Caucasian vs other groups) | 1.68, 95% CI 1.37 to 2.06 (Caucasians) | χ2 (1) = 5.01 | p < .001 |

| Scripps Health employee status | 0.68, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.81 (employees) | χ2 (1) = − 4.13 | p < .001 |

| Highest completed education | 1.12, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.17 (higher education) | χ2 (1) = 4.49 | p < .001 |

| Age (quadratic and linear) | Quadratic: 1.0007, 95% CI 1.0003 to 1.001 | χ2 (1) = 3.33 | p = .001 |

| Linear: 0.984, 95% CI 0.98 to 0.99 | χ2 (1) = − 4.99 | p < .001 | |

| Sex | 0.905, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.05 (females) | χ2 (1) = − 1.34 | p = .182 |

| Trait anxiety | 1.005, 95% CI 0.997 to 1.013 | χ2 (1) = 1.37 | p = .172 |

| Household income | 1.00, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.04 | χ2 (1) = − 0.01 | p = .996 |

| Primary language other than English | 0.813, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.02 (other primary language) | χ2 (1) = − 1.81 | p = .070 |

Ancestry survey completion

Age, highest completed education, and primary language other than English were statistically significant predictors of ancestry survey completion (see Table 3). Those with higher completed education were more likely to complete the ancestry survey, while those who indicated another language as their primary language were less likely to complete the survey. Both linear and quadratic age terms were statistically significant. Specifically, 53–54-year-olds had the highest predicted probability of completing the ancestry survey (27.8%), while 18–19-year-olds had the lowest predicted probability (11.6%).

Table 3.

Breakdown of results for completing ancestry results survey

| Ancestry results survey completion | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio | Wald test | p value |

| Ethnicity/race (i.e., Caucasian vs other groups) | 1.17, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.84 (Caucasians) | χ2 (1) = 0.66 | p = .51 |

| Scripps Health employee status | 0.89, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.27 (employees) | χ2 (1) = − 0.62 | p = .54 |

| Highest completed education | 1.13, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.24 (higher education) | χ2 (1) = 2.73 | p = .006 |

| Age (quadratic and linear) | Quadratic: 0.999, 95% CI 0.9983 to 0.9999 | χ2 (1) = − 2.18 | p = .03 |

| Linear: 1.01, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.03 | χ2 (1) = 2.35 | p = .02 | |

| Sex | 1.19, 95% CI 0.914 to 1.55 (females) | χ2 (1) = 1.29 | p = .20 |

| Trait anxiety | 0.999, 95% CI 0.987 to 1.013 | χ2 (1) = 0.98 | p = .98 |

| Household income | 0.967, 95% CI 0.894 to 1.045 | χ2 (1) = − 0.85 | p = .40 |

| Primary language other than English | 0.62, 95% 0.39 to 0.99 (other primary language) | χ2 (1) = − 2.00 | p = .045 |

| Discrepant ancestry results | 1.37, 95% CI 0.081 to 0.445 | χ2 (1) = 0.84 | p = .40 |

Impacts of ancestry testing

Table 4 summarizes responses to the ancestry testing survey. While nearly half of respondents (46%; N = 147) reported that their results were surprising or somewhat surprising (11.5% and 34.2%, respectively), less than 1% were distressed by the results. However, a notable fraction of respondents indicated that their DNA ancestry results affected their cultural or personal identity. For instance, ~ 40% indicated results changed (12.1%) or somewhat changed (27.0%) perceptions of their cultural roots, and ~ 20% indicated results reshaped (4.0%) or somewhat reshaped (16.8%) their personal identity. Similarly, nearly a quarter of respondents reported that their results changed (12.4%) or somewhat changed (11.5%) the likelihood that they would travel to certain parts of the world, and 12.4% indicated that results changed (5.6%) or somewhat changed (6.8%) how they view certain cultures or world regions. A majority (80.7%) reported “yes,” that they planned to share their results with family members, and 12.1% reported “yes,” that they intended to share with a healthcare provider. Of the participants who reported an intention to share with a healthcare provider, most self-identified as Caucasian (82%) and were genetically most similar to people from Europe (89.7%). There were no statistically significant differences with regard to intentions to share with a healthcare provider by self-reported race/ethnicity or overall ancestry (p = .28 and p = .25, respectively). Also, 7.7% were coded as having discrepant results, which was not statistically significantly different from the other survey responders (p = .21). Lastly, over half (50.3%) of all survey responders reported being more likely to have other genetic tests in the future.

Table 4.

Participant responses to questions regarding the impact of personal genetic ancestry testing (N = 322)

| Domain | Item | Ancestry response item N (%) | No | Somewhat/maybe | Yes | Missing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General response | 1 | Were your ancestry test results surprising or unexpected? | 175 (54.3%) | 110 (34.2%) | 37 (11.5%) | -- |

| 2 | Were your ancestry test results undesired or distressing? | 319 (99.1%) | 3 (0.9%) | 0 | -- | |

| Cultural/personal identity | 3 | Do your ancestry test results change your perceptions of your cultural roots? | 193 (59.9%) | 87 (27.0%) | 39 (12.1%) | 3 (0.9%) |

| 4 | Do your ancestry test results change the likelihood that you would travel to certain parts of the world in the future? | 244 (75.8%) | 37 (11.5%) | 40 (12.4%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| 5 | Do your ancestry test results change how you view certain cultures or world regions? | 280 (87.0%) | 22 (6.8%) | 18 (5.6%) | 2 (0.6%) | |

| 6 | Would you say your ancestry test results have reshaped your personal identity? | 245 (76.1%) | 54 (16.8%) | 13 (4.0%) | 10 (3.1%) | |

| Sharing results | 7 | Do you plan to share your ancestry test results with your family members? | 17 (5.3%) | 43 (13.4%) | 260 (80.7%) | 2 (0.6%) |

| 8 | Will you provide or discuss your ancestry test results with your physician or a healthcare provider? | 156 (48.8%) | 124 (38.5%) | 39 (12.1%) | 3 (0.9%) | |

| Ancestry testing | 9 | Have you had other ancestry testing in the past? | No | Not sure | Yes | Missing |

| 292 (90.7%) | 2 (0.6%) | 26 (8.1%) | 2 (0.6%) | |||

| 10 | If yes, do you perceive your current* ancestry test results to be different than your previous results? | No | Somewhat | Yes | Missing | |

| 17 (65.4%) | 6 (23.1%) | 3 (11.5%) | – | |||

| 11 | Does the experience of undergoing genetic ancestry testing make you more or less likely to have other genetic tests in the future? | Less likely | No change | More likely | Missing | |

| 6 (1.9%) | 152 (47.2%) | 162 (50.3%) | 2 (0.6%) |

*Skip logic was not used for item 9; thus, results exclude 82 individuals that did not respond “yes” to item 9 but responded to item 10

Predictors of ancestry testing impacts

Table 5 depicts the linear regression results. None of the 10 independent variables significantly predicted surprise, distress, or reshaping of personal identity in response to DNA ancestry testing. Trait anxiety was a significant predictor of change in perceived cultural roots, with higher trait anxiety being associated with greater change in perceived cultural roots. Baseline (pre-test) self-reported race/ethnicity, trait anxiety, and past ancestry testing were significant predictors of both changes in the likelihood of traveling to certain parts of the world and change in views of certain cultures or world regions. In each case, individuals whose self-reported race/ethnicity was a category other than “Caucasian” were more likely to be affected compared with those who self-reported as “Caucasian” at baseline. In addition, higher trait anxiety was associated with greater impacts/changes and having had previous ancestry testing was also associated with greater impacts/changes.

Table 5.

Linear regression results of ancestry testing impact survey

| Surprising N = 319 | Undesired N = 319 | Perception N = 316 | Travel N = 318 | Culture N = 318 | Reshape identity N = 309 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | t test | p value | t test | p value | t test | p value | t test | p value | t test | p value | t test | p value |

| Ethnicity/race (i.e., Caucasian vs other groups) | − 1.38 | .17 | − 0.82 | .411 | 0.40 | .680 | − 1.99 | .047 | − 2.01 | .045 | − 1.14 | .254 |

| Scripps Health employee status | − 0.89 | .375 | 0.44 | .660 | 0.56 | .579 | − 0.50 | .620 | 1.06 | .288 | 0.71 | .480 |

| Highest completed education | − 1.51 | .131 | − 0.93 | .355 | 0.94 | .347 | − 0.65 | .515 | − 1.55 | .122 | − 1.77 | .078 |

| Age (quadratic and linear) | Quadratic − 0.48 | .633 | Quadratic − 1.70 | .09 | Quadratic 0.15 | .884 | Quadratic 0.76 | .446 | Quadratic 0.16 | .874 | Quadratic − 0.45 | .653 |

| Linear 0.76 | .446 | Linear 1.18 | .24 | Linear − 0.66 | .512 | Linear − 1.23 | .220 | Linear 0.15 | .878 | Linear − 0.80 | .427 | |

| Sex | 0.37 | .709 | 1.87 | .063 | 1.53 | .127 | 0.81 | .420 | 0.07 | .946 | − 0.51 | .608 |

| Trait anxiety | − 0.20 | .839 | 0.23 | .821 | 2.22 | .027 | 2.14 | .033 | 2.31 | .021 | 1.00 | .319 |

| Household income | − 0.63 | .531 | 0.15 | .880 | 0.41 | .68 | − 0.18 | .855 | 0.57 | .572 | − 0.13 | .893 |

| Primary language other than English | − 1.01 | .315 | 1.39 | .166 | − 1.16 | .247 | − 1.76 | .080 | 0.19 | .848 | − 0.55 | .580 |

| Discrepant ancestry results | − 0.47 | .641 | − 1.38 | .169 | − 1.24 | .217 | − 0.81 | .417 | − 0.70 | .486 | − 0.70 | .487 |

| Past ancestry testing | 0.31 | .754 | − 0.15 | .879 | 0.97 | .331 | 2.43 | .016 | 2.86 | .005 | 1.34 | .181 |

Perceived advantages and disadvantages

A total of 61.2% of participants reported at least one advantage to receive ancestry results, 12.1% reported at least one disadvantage, and 35.7% did not report either an advantage or disadvantage. Specifically, 3.1% reported only a disadvantage and no advantage, 52.2% reported only advantage and no disadvantage, and 9.0% reported both advantages and disadvantages. For advantages, participants most frequently reported that the ancestry results satisfied a natural curiosity. Other advantages were helping to confirm what was already known or suspected about their identity, learning heritage-related information, providing potential health insights, and influencing future decision-making. For disadvantages, participants most frequently reported receiving unwelcome or unexpected information. Other reported disadvantages were a lack of utility, skepticism of the trustworthiness or accuracy of the results, and a possibility of the results reinforcing bias or racism. See Table 6 for a list of emergent themes for advantages and disadvantages with example quotes and frequencies.

Table 6.

Emergent themes about perceived advantages and disadvantages of receiving ancestry results

| Advantages | Frequency | Example quote |

|---|---|---|

| - General interest/curiosity | 62/322 = 19.3% | “It satisfies a natural curiosity. It also had some surprising elements to it which will lead me to do some more investigations into our family tree.” |

| - Health insights | 46/322 = 14.3% | “I believe that knowing genetic ancestry would help in knowing possible health risks certain genetic populations lean towards and to take precautions to prevent these health risks. Knowledge is power!” |

| - Confirmation of what was suspected or known | 56/322 = 17.4% | “I feel it only confirmed the history my family had already traced back as far as they could with written records. All the results were spot on and truly not surprising just reassuring.” |

| - Learning heritage-related information | 55/322 = 17.1% | “Totally changes my perception of family roots. I am now interested in [d]oing family research.” |

| - Influence decision-making | 40/322 = 12.4% | “Verifying information that I was told and did not really think was even possible. It could influence decisions on future testing if the choice is needed.” |

| Disadvantages | ||

| - Lack of utility | 7/322 = 2.2% | “Again, it was too general/broad to have any advantages or disadvantages.” |

| - Unwelcome/unexpected information | 19/322 = 5.9% | “It counters what my folks have been telling me all along. I do not think I’ll share this info with them as it contradicts so much of what they consider our ‘roots’.” |

| - Skepticism of accuracy/trustworthiness of results | 7/322 = 2.2% | “Not sure I trust the results. My highest hit was Bergamo, a Southern European group. And I am a melanin-deprived Northern European white girl.” |

| - Possibility of reinforcing bias/racism | 3/322 = 0.9% | “It may make me biased toward/against a certain ethnicity.” |

Statistical analyses suggest that reporting an advantage was significantly associated with indicating that the ancestry results changed one’s perception of cultural roots (t(316) = 2.00, p = .047), as well as indicating intention to share results with family members (t(317) = 3.24, p = .001) and physicians or healthcare providers (t(316) = 2.88, p = .004). Reporting a disadvantage was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of intention to share results with family members (t(317) = − 2.92, p = .004).

Discussion

This study examined the impacts of DNA ancestry testing on participants within the context of a broader study evaluating the psychological and behavioral impacts of health-related DTC genomic testing (Bloss et al., 2011). Using quantitative and qualitative approaches, we examined participants’ responses to DNA ancestry testing in a survey study. The study included the evaluation of health-related impacts and assessed predictors of accessing DNA ancestry results.

The data suggest that the majority of participants were not distressed by their DNA ancestry results, yet many found the results to be impactful. Almost half of the survey respondents indicated some change in their perception of their cultural roots, and nearly a quarter felt the results reshaped their cultural identity. These data are consistent with previous research findings that suggest ancestry results have moderate impacts on identity, including self-identification reporting patterns (Damotte et al., 2019). Estimates in the literature range from ~ 12 to ~ 50% of participants reporting changes in perceived race, ethnicity, or identity (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Foeman et al., 2015; Wagner & Weiss, 2012). Our results, in combination with past findings, have implications for cultural identity formation with important possible downstream effects on identity reporting initiatives, such as the U.S. Census. Indeed, the potential for DNA ancestry test results to prompt changes in how recipients respond to the U.S. Census has been discussed in the literature (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Blanchard et al., 2017) with one study of 45 undergraduate students suggesting one-third changing their census identification (Foeman et al., 2015). We recognize that the categorizations of ancestry and self-reported race and ethnicity used in this study limit the findings as they differ from the U.S. Census including its option for multiraciality. Nevertheless, even the U.S. Census is not static on its framing of demographic questions and iterates across census surveys (What Census Calls Us, 2015).

Study participants reported benefits of receiving test results similar to those discussed in the literature, such as curiosity, entertainment, learning more about ancestry, genealogical research, interest in technology, access to personal information, and health-related interests (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Foeman et al., 2015; Nelson, 2008; Wagner & Weiss, 2012). Our results also suggest that self-reported race/ethnicity, trait anxiety, and past ancestry testing might act as mediators of change in individuals’ propensity to travel to certain parts of the world and individuals’ views of certain cultures or world regions. Specifically, the data augment what has previously been observed regarding differences in the impact of test results on individuals who self-identify as White versus other races. Previously, some researchers have discussed the ways in which White individuals more readily integrate new ethnic or racial identities (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018), while another study suggested that those of European background were less likely to change their self-identification (Foeman et al., 2015). In our study sample, self-reported Caucasians were less likely to be affected with respect to travel or views of cultures or world regions. Thus, while findings in the literature are mixed on whether or not these individuals are more likely to integrate new identities, our study data suggest they might possibly be less likely to change perspectives or behaviors. Different categorizations and options for classifying self-reported race and ethnicity across studies might also account for the mixed findings. Additionally, we found no significant association between testing impacts and ancestry results that were considered discrepant relative to baseline self-reported race/ethnicity, which aligns with previous research findings and theories that argue an individual’s family and cultural upbringing might be more influential for identity formation than scientific information (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Foeman et al., 2015; Lawton & Foeman, 2017; Blanchard et al., 2019). Baseline trait anxiety was positively associated with changed perceptions after testing related to world travel and views of cultures and regions. This finding adds to previous research findings that suggest baseline anxiety levels may be a susceptibility factor for being affected by genomic test results (Dorval et al., 2000; Duisterhof et al., 2001; Michie et al., 2001; Gray et al., 2014); thus, these individuals may benefit from more resources. Nevertheless, our sample of research participants could differ from current DTC consumers seeking ancestry information specifically, and, individual motivations and expectations should be taken into account when contextualizing the impact of ancestry test results.

Consistent with other studies, our participants also reported similar negative aspects of testing, such as receiving unwelcome or unexpected information which could complicate one’s understanding of their ancestry (Foeman et al., 2015; Nelson, 2008). It has been suggested that identity changes are a result of an “interplay of macro-, meso-, and micro-level processes” (Nelson, 2008); thus, receiving test results might be just one piece of a larger process of understanding one’s identity (Blanchard et al., 2019). Others have previously written about the intersection of DNA ancestry testing, genetic determinism, and racism (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Byrd & Hughey, 2015; Heine, 2017; Mittos et al., 2018) as well as the potential for DNA ancestry tests to reinforce discriminatory rhetoric and behavior (Foeman et al., 2015). Our results are consistent with this possibility but suggest that such impacts might be rare among individuals who receive DNA ancestry testing in the context of research (i.e., in our study, only three individuals, or 1% of the 322 respondents, raised the possibility of reinforcing bias and racism as a disadvantage of testing). Nevertheless, 1% reporting possibility of reinforcing bias and racism, when scaled up, is the equivalent of approximately 260,000 of the 26 million individuals who have taken DTC ancestry testing in the USA as of early 2019 (Regalado, 2019). Furthermore, the data were collected in 2010 and interest in DTC ancestry testing has steadily increased with more Americans engaging in DTC ancestry testing than in all previous years combined (Regalado, 2019). We thus suspect that the study findings are even more pertinent now. It is also possible that more participants might endorse the possibility of reinforcing bias and racism if explicitly asked (Foeman et al., 2015). Future research investigating differences in discriminatory rhetoric and behavior as a result of ancestry testing should be pursued in the consumer marketplace as well as in research contexts using both test taker and observational perspectives.

Our results raise the possibility that DNA ancestry tests might impact patterns of communication with one’s family, friends, and communities. Specifically, most of the survey respondents (> 80%) reported intending to share their results with their family members, which aligns with one previous study (Foeman et al., 2015). Notably, however, those who reported a disadvantage in receiving their results were less likely to do so (e.g., one hypothesis to explain this could be that the results contradicted what the respondents thought about themselves based on family narratives). Thus, it is possible that these respondents chose to navigate the contradiction (Royal et al., 2010) by keeping the results to themselves and dismissing them, ultimately, rather than sharing the results and potentially disrupting familial bonds which are constructed socially as well as biologically (Garrison & Bardill, 2019; Blanchard et al., 2019). Participants who reported an advantage were more likely to report a change in their perception of their cultural roots and intention to share results with family members. These findings might be explained by the concept of “ancestral certainty” or one’s confidence in knowing their ancestral background (Horowitz et al., 2019). Individuals with less ancestral certainty might be more influenced or affected by ancestry results and, thus, be more likely to integrate the results, which leads to changes in perceived cultural roots or desire to share results with family members.

Individuals whose self-reported race/ethnicity was a category other than “Caucasian” (i.e., “African-American,” “Hispanic/Latino,” “Asian,” “American Indian/Alaskan Native,” “Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander”) were, as a group, significantly less likely to log on to view their ancestry results in the study. One explanation might be that individuals in these self-reported groups endorse more ancestral certainty, compared with self-reported White individuals (Horowitz et al., 2019). Findings from one study suggest that self-identified Asian, Black/African-American, and Hispanic/Latino participants tend to endorse more ancestral certainty, which affects and often reduces their interest in engaging with ancestry testing (Horowitz et al., 2019). Another explanation stems from the hypothesis that ancestry testing might reinforce racial privileges. For example, ancestry testing has been used to reinforce White privilege and eugenics rhetoric among White supremacists (Mittos et al., 2018), and ancestry results have been appropriated to claim entitlement to tribal or scholarship benefits reserved for indigenous or minority groups (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Bolnick et al., 2007a; Garrison, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Kirkpatrick & Rashkin, 2017; Foeman et al., 2015; Blanchard et al., 2017; Blanchard et al., 2019). A third explanation might be that individuals who self-identified as a category other than “Caucasian” in our study were only interested in the health-related genomic testing that was part of the larger SGHI longitudinal study and not the ancestry testing component. While both health-related genomic testing and DNA ancestry testing were part of the SGHI study, participants might have enrolled primarily for health-related genomic testing results. Indeed, over the years, DTC genomic testing companies have split up their ancestry and health-related genomic testing products to meet consumer trends and niche interests in response to their consumers purchasing the different tests with distinct motivations (Macarthur, 2009).

Individuals with higher completed education were more likely to access their results and complete our survey. These results align with previous findings in the literature that individuals with more completed education might be most interested in ancestry testing. Past research suggests that older individuals are most interested in ancestry testing (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Nelson, 2008; Horowitz et al., 2019; Greely, 2008), hypothesized as a reflection in trends of older adults’ interest in genealogy (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Nelson, 2008; Greely, 2008). Our data provide partial support for past research findings. Specifically, younger participants (18–19-year-olds) had the highest likelihood of accessing their ancestry results online, but older participants (53–54-year-olds) were most likely to complete the ancestry results survey. We interpret these findings in the following way: due to younger participants’ familiarity with and fluency in technology use from a young age, logging on to view results required minimal effort, thus reflecting the observed rates of younger participants viewing online results. This interpretation is also supported by low levels of engagement in survey completion by our younger participants despite having consented to participate in a larger study evaluating the psychological and behavioral impacts of health-related DTC genomic testing (Bloss et al., 2011). Lastly, individuals who indicated a primary language other than English were less likely to complete the ancestry results survey, which is unsurprising given it was provided only in English.

Over 12% of respondents reported intending to share the results with their physicians or healthcare providers, and reporting any advantage to the test results was positively associated with an intention to share results with a physician or healthcare provider. Over 14% of respondents reported health insights as an advantage of the results; thus, one explanation might be that respondents want to share their ancestry results with providers because respondents view the information as health related. Furthermore, we found no differences or associations with regard to intention to share results with a healthcare provider and self-reported race/ethnicity, overall ancestry, or discrepant results. Cases have been made for (Kirkpatrick & Rashkin, 2017) and against the clinical utility of ancestry testing (Kirkpatrick & Rashkin, 2017; Blell & Hunter, 2019), nevertheless, with (1) over half of our respondents reporting interest in pursuing other genetic tests in the future; (2) a considerable proportion reporting a desire to share ancestry results with providers; and (3) the direction of commercial entities moving towards offering and integrating ancestry and health-related genetic testing (Petrone, 2019; Ramsey, 2019; Ray, 2019; Rubin & Dockser, 2019), providers will likely continue to experience increased volumes and complexity of genetic data as part of care management. Thus, studying the impacts of personal ancestry testing is of critical importance for the medical community (Royal et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2018). Our findings also raise questions related to how and if physicians and healthcare providers are able to manage ancestry data in the clinical encounter, especially as interest in DTC ancestry testing has grown since the time these data were collected (Regalado, 2019). Concerns have previously been noted about physician and healthcare provider education and training in the area of genomics (Feero & Green, 2011; Marshall, 2011; Mainous 3rd et al., 2013; Hamilton et al., 2017; Wilkes et al., 2017; Rubanovich et al., 2018), and whether they have the requisite knowledge and experience to adequately address questions and carry out clinical care related to genomics (Marshall, 2011; Stanek et al., 2012), let alone, to the specifics of DNA ancestry results (Garrison & Bardill, 2019; Nelson et al., 2018). Previous data also suggest that test takers are motivated to utilize third-party online services that interpret raw data (e.g., Promethease) and bring these results to physicians for clinical assistance in interpretation (Gollust et al., 2017). Furthermore, biomedical and medical genetics researchers contemplating returning ancestry results to participants as a study incentive should consider the complexities and consequences raised here about the behavioral and attitudinal impacts.

Limitations

Our study has several important limitations. First, the data were collected in 2010 and, as a result, are possibly not reflective of current attitudes and trends among those who are interested in or engage with DNA ancestry testing, especially given the growing popularity of these products. Our data collection is, however, within the same timeframe as other studies examining impacts of ancestry test results as follows: 2009–2010 (Roth & Ivemark, 2018), 2009–2011 (Roth & Lyon, 2018), and 2011–2012 (Foeman et al., 2015). These studies, despite being focused on early users of genetic ancestry testing, can help the design of future scientific studies. Second, the ancestry results had limitations as participant genotypes were compared with a sample of 3000 reference individuals. This represents only a fraction of all known or relevant populations (Royal et al., 2010) that are now available to construct ancestry estimates. Third, the DNA ancestry test results were estimated in-house and not by a commercial provider, even though the website developed had many features similar to the commercial products available at that time. While this difference limits generalizability, the findings do have transferability worthy of future investigation in current DTC offerings. Fourth, the amount of time that passed between a participant viewing their results and completing the survey was not tracked. Most participants would likely have completed the survey immediately after viewing their results because that is when they would have been prompted to do so by the appearance of the survey link. However, because we did not track this, we are unable to draw correlations between time to process the results and impacts. Fifth, we did not collect participant self-reported ancestry as part of the impacts survey; thus, our ability to draw conclusions about changes in ancestry pre- and post-testing is limited. We attempted to look at discrepancies between self-reported race/ethnicity and participants’ overall ancestry estimates using consensus coding. However, we recognize the limitations of this approach given the complexities in matching ancestry and self-reported race/ethnicity which are not synonymous. These data should be interpreted with caution.

We also acknowledge the limitations of the item wording and response options used in the baseline survey demographic items. Specifically, responders saw stimuli that asked: “[w]hat is your ethnicity?”; however, stimuli asking: “[h]ow do you identify?” with the inclusion of a multi-response format and more inclusive response options would have allowed for participants to answer in a more nuanced and self-representative fashion to items of ethnicity and race. The wording of these items and the response options provided are restricted relative to present-day standards. While the approach was similar to wording and response options used in demographic questions in other biomedical studies conducted during the same timeframe, we acknowledge the way these stimuli were phrased might have limited participants’ ability to self-report precisely and, therefore, created limitations to the subsequent analysis and interpretation. Future studies will benefit from self-report demographic items with more inclusive and multiraciality options that allow respondents to better represent themselves. Sixth, our findings are limited in their generalizability given our highly educated, wealthy, predominately self-reported Caucasian sample. This limitation is mirrored in previous studies as well (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Wagner & Weiss, 2012). Some studies (Nelson, 2008; Jonassaint et al., 2010) have been more successful in recruiting more diverse populations, and we emphasize the importance of recruiting more inclusive samples in future studies. Relatedly, due to smaller sample sizes in other ascribed racial/ethnic groups (i.e., other than Caucasian), self-reported race/ethnicity was dichotomized in our study to increase statistical power and, as a result, limited our ability to study potential inter-group differences. Future research would benefit from a study statistically powered to explore potential intra- and inter-group similarities and differences.

Finally, scholars have previously written about the ways in which the “sociotechnical architecture” of technologies impact how users experience information presented through technologies. In this study, the very design of the results interface might impact participant engagement with and understanding of their results (Parthasarathy, 2010). We are unable to partial out the effect of the return of results interface on the impacts of the genetic ancestry results. A further investigation comparing the potential effect of interfaces for communicating and interacting with DNA ancestry testing results is warranted. Moreover, we also did not assess response to individual components of the genetic ancestry report that were provided (i.e., population likelihood strategy, world-wide matching strategy, global coordinates strategy), and it is possible that participants’ responses differed based on which strategy they focused on or time spent looking at one strategy versus another. Lastly, we did not assess the degree to which other educational information and webpages accessible to participants on the interface may have impacted their understanding of the results or have influenced the impact of the results.

Future directions

DTC DNA ancestry testing’s recent and projected growth has critical policy implications in a variety of settings (Roth & Lyon, 2018; Roth & Ivemark, 2018; Blanchard et al., 2017; Blanchard et al., 2019). The perceived lack of oversight of DTC DNA ancestry testing by regulatory bodies has raised concerns about its uses (Wagner et al., 2012), especially in high-stake settings such as healthcare, U.S. Census reporting, Native American tribal affiliation, college admissions, and job enrollment (Phillips, 2016; Smart et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2009; Ramos & Weissman, 2018; Wagner & Weiss, 2012). We thus stress the need for future research that includes an appropriately powered and inclusive longitudinal study to examine the psychosocial and health behavioral impacts of DTC DNA ancestry testing. Specifically, we recommend a pre/post-study design with immediate and long-term follow-up timepoints. To date, the few empirical data that exist suggest that most test takers are not adversely affected by test results; however, a sizeable proportion reports a shift in their self-identity. Future research should consider both the immediate and long-term effects of DNA ancestry testing on test recipients as available data are limited and further study could clarify the impact on test takers’ attitudes and behaviors. We recommend using both personal ancestry and more granular racial categorization in combination for participant self-identification (Damotte et al., 2019). Additionally, future research would benefit from studying the impact(s) of an individual’s DNA results on others (e.g., family members, community members, and/or societal bystanders) as our data, along with previously published findings, suggest that test takers are interested in sharing results with others yet few data exist examining how others react or use this information in decision-making (e.g., their own medical care). Related ethical issues to explore include (1) intergenerational consent (Juengst, 2004) and (2) data privacy related to law enforcement reliance on genetic genealogy for re-identification purposes and as a crime-solving tool to supplement formal CODIS databases (Garrison & Bardill, 2019; Wagner & Weiss, 2012; Clayton et al., 2018; Guerrini et al., 2018; Ram et al., 2018; Department of Justice US, 2019).

Conclusion

Empirical studies examining the impacts of DNA ancestry testing are scant, despite the DTC ancestry industry being two decades old. This paper is the first, to our knowledge, to report on health-related impacts from engaging in genetic ancestry testing and is one of the very few studies in the literature overall that has studied recipients of genetic ancestry tests. We hope that this work will motivate future research that will help us understand how and whether DTC DNA ancestry testing alters healthcare (e.g., quality of care, access to care, utilization of care), health behaviors (e.g., perceived health risks, disease prevention), and health outcomes (e.g., if there are actual health effects, psychosocial stress, altered experience of discrimination), as well as willingness to participate in other genetic research.

Electronic supplementary material

Screenshot of interactive website with genetic ancestry results (PNG 295 kb)

Screenshot of population likelihood strategy – global view (PNG 225 kb)

Screenshot of population likelihood strategy – regional view (PNG 232 kb)

(DOCX 13 kb)

(DOCX 12 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

(DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Erin Smith Ph.D. and Vikas Bansal Ph.D. for their contributions to the development of the DNA ancestry testing pipeline; Debra L. Boeldt Ph.D. for her contributions to an earlier draft of the manuscript; and Lisette Diaz for her assistance conducting literature searches.

Appendix

Impact of ancestry test results survey

Were your ancestry test results surprising or unexpected? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Were your ancestry test results undesired or distressing? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Do your ancestry test results change your perceptions of your cultural roots? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Do your ancestry test results change the likelihood that you would travel to certain parts of the world in the future? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Do your ancestry test results change how you view certain cultures or world regions? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Would you say your ancestry test results have reshaped your personal identity? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Do you plan to share your ancestry test results with your family members? Responses: (Yes, No, Maybe)

Will you provide or discuss your ancestry test results with your physician or a healthcare provider? Responses: (Yes, No, Maybe)

Have you had other ancestry testing in the past? Responses: (Yes, No, Not Sure)

If yes, do you perceive your current ancestry test results to be different than your previous results? Responses: (Yes, No, Somewhat)

Does the experience of undergoing genetic ancestry testing make you more or less likely to have other genetic tests in the future? Responses: (More Likely, Less Likely, No Change)

What are the advantages to learning your estimated genetic ancestry? Responses: (Open-ended)

What are the disadvantages to learning your estimated genetic ancestry? Responses: (Open-ended)

Authors’ contributions

Caryn Kseniya Rubanovich: Conducted analysis and interpretation of survey data; produced the first draft of the manuscript; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Riley Taitingfong: Conducted analysis of survey data; drafted some sections of the manuscript; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Cynthia Triplett: Conducted analysis of survey data; drafted some sections of the manuscript; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Ondrej Libiger: Conducted analysis of genetic data; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Nicholas J. Schork: Contributed to the conception and design of the work and the acquisition of data; conducted analysis and interpretation of genetic data; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Jennifer K. Wagner: Contributed to interpretation of survey data; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Cinnamon S. Bloss: Contributed to the conception and design of the work and the acquisition of data; conducted analysis and interpretation of genetic and survey data; revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content

Funding information

This work was supported in part by two grants from the National Human Genome Research Institute (R01 HG008753, PI: Bloss, R21 HG005747 PI: Bloss), a NIH flagship Clinical and Translational Science Award grant (5UL1RR025774, 8UL1 TR000109, and 8UL1 TR001114; PI: Eric J. Topol, M.D.), and Scripps Genomic Medicine Division of Scripps Health. JKW’s contribution was supported in part by NHGRI Grant No. 5R00HG006446-05. CKR and RT’s contributions were supported in part by the UC San Diego Chancellor’s Interdisciplinary Collaboratory. CKR was also supported by a San Diego State University Graduate Fellowship.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of ethics

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the institutional review board at Scripps Health and The Scripps Research Institute.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained electronically from each study participant.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bader AC, Malhi RS. Case study on ancestry estimation in an Alaskan native family: identity and safeguards against reductionism. Hum Biol. 2015;87(4):338–351. doi: 10.13110/humanbiology.87.4.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JW, Tallbull G, Wolpert C, Powell J, Foster MW, Royal C. Barriers and strategies related to qualitative research on genetic ancestry testing in indigenous communities. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2017;12(3):169–179. doi: 10.1177/1556264617704542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JW, Outram S, Tallbull G, Royal CD, Leroux D, Lund J, et al. We Don’t need a swab in our mouth to prove who we are. Curr Anthropol. 2019;60(5):000–000. doi: 10.1086/705483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blell M, Hunter M (2019) Direct-to-consumer genetic testing’s red herring:“genetic ancestry” and personalized medicine. Frontiers in medicine 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bloss CS, Ornowski L, Silver E, Cargill M, Vanier V, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Consumer perceptions of direct-to-consumer personalized genomic risk assessments. Genetics in Medicine. 2010;12(9):556–566. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181eb51c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss CS, Schork NJ, Topol EJ. Effect of direct-to-consumer genomewide profiling to assess disease risk. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):524–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolnick DA (2008) Individual ancestry inference and the reification of race as a biological phenomenon. Revisiting race in a genomic age:70–85

- Bolnick DA, Fullwiley D, Duster T, Cooper RS, Fujimura JH, Kahn J, et al. Genetics. The science and business of genetic ancestry testing. Science. 2007;318(5849):399–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1150098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolnick DA, Fullwiley D, Duster T, Cooper RS, Fujimura JH, Kahn J, Kaufman JS, Marks J, Morning A, Nelson A, Ossorio P, Reardon J, Reverby SM, TallBear K. The science and business of genetic ancestry testing. Science. 2007;318(5849):399–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1150098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Khoury M. Consumer genetic testing is booming: but what are the benefits and harms to individuals and populations? 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brown K (2018). How DNA testing botched my family’s heritage, and probably yours, too. Gizmodo

- Byrd WC, Hughey MW. Biological determinism and racial essentialism: the ideological double helix of racial inequality. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA; 2015

- Clayton EW, Halverson CM, Sathe NA, Malin BA. A systematic literature review of individuals’ perspectives on privacy and genetic information in the United States. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204417. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damotte V, Zhao C, Lin C, Williams E, Louzoun Y, Madbouly A, et al. Multiple measures reveal the value of both race and geographic ancestry for self-identification. bioRxiv. 2019;2019:701698. [Google Scholar]

- DeFabio CR. Splinter News. 2016. If you’re black, DNA ancestry results can reveal an awkward truth. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Justice US . Forensic Genetic Genealogical Dna Analysis And Searching. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dockser MA. The Wall Street Journal. 2018. For some African-Americans, genetic testing reopens past wounds. [Google Scholar]

- Dorval M, Patenaude AF, Schneider KA, Kieffer SA, DiGianni L, Kalkbrenner KJ, Bromberg JI, Basili LA, Calzone K, Stopfer J, Weber BL, Garber JE. Anticipated versus actual emotional reactions to disclosure of results of genetic tests for cancer susceptibility: findings from p53 and BRCA1 testing programs. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2135–2142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duisterhof M, Trijsburg RW, Niermeijer MF, Roos RA, Tibben A. Psychological studies in Huntington’s disease: making up the balance. J Med Genet. 2001;38(12):852–861. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.12.852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott C, Brodwin P. Identity and genetic ancestry tracing. Bmj. 2002;325(7378):1469–1471. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feero WG, Green ED. Genomics education for health care professionals in the 21st century. JAMA. 2011;306(9):989–990. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foeman A, Lawton BL, Rieger R. Questioning race: ancestry DNA and dialog on race. Commun Monogr. 2015;82(2):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Francke U, Dijamco C, Kiefer AK, Eriksson N, Moiseff B, Tung JY, Mountain JL. Dealing with the unexpected: consumer responses to direct-access BRCA mutation testing. PeerJ. 2013;1:e8. doi: 10.7717/peerj.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison NA. Genetic ancestry testing with tribes: ethics, identity & health implications. Daedalus. 2018;147(2):60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison NA, Bardill JD (2019) The ethics of genetic ancestry testing. A Companion to Anthropological Genetics:17–35

- Gollust S, Gray S, Carere D, Koenig B, Lehmann L, McGuire A, et al. Consumer perspectives on access to direct-to-consumer genetic testing: role of demographic factors and the testing rxperience. Milbank Quarterly. 2017;95(2):291–318. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SW, Martins Y, Feuerman LZ, Bernhardt BA, Biesecker BB, Christensen KD, et al. Social and behavioral research in genomic sequencing: approaches from the clinical sequencing exploratory research consortium outcomes and measures working group. Genetics in Medicine. 2014;16(10):727–735. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greely HT (2008) Genetic genealogy: genetics meets the marketplace. Revisiting race in a genomic age.:215–234

- Guerrini CJ, Robinson JO, Petersen D, McGuire AL. Should police have access to genetic genealogy databases? Capturing the Golden State Killer and other criminals using a controversial new forensic technique. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(10):e2006906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeusermann T, Greshake B, Blasimme A, Irdam D, Richards M, Vayena E. Open sharing of genomic data: who does it and why? PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeusermann T, Greshake B, Blasimme A, Irdam D, Richards M, Vayena E. Open sharing of genomic data: who does it and why? Plos One. 2017;12(5):e0177158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JG, Abdiwahab E, Edwards HM, Fang M-L, Jdayani A, Breslau ES. Primary care providers’ cancer genetic testing-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication behaviors: a systematic review and research agenda. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):315–324. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3943-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine SJ (2017) DNA is not destiny: the remarkable, completely misunderstood relationship between you and your genes. WW Norton & Company

- Helgadottir A, Manolescu A, Helgason A, Thorleifsson G, Thorsteinsdottir U, Gudbjartsson DF, Gretarsdottir S, Magnusson KP, Gudmundsson G, Hicks A, Jonsson T, Grant SFA, Sainz J, O’Brien SJ, Sveinbjornsdottir S, Valdimarsson EM, Matthiasson SE, Levey AI, Abramson JL, Reilly MP, Vaccarino V, Wolfe ML, Gudnason V, Quyyumi AA, Topol EJ, Rader DJ, Thorgeirsson G, Gulcher JR, Hakonarson H, Kong A, Stefansson K. A variant of the gene encoding leukotriene A4 hydrolase confers ethnicity-specific risk of myocardial infarction. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):68–74. doi: 10.1038/ng1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesman ST. ScienceNews. 2018. DNA testing can bring families together, but gives mixed answers on ethnicity. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman EC, Panther-Yates D. Peering inward for ethnic identity: consumer interpretation of DNA test results. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2008;8(1):47–66. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz AL, Saperstein A, Little J, Maiers M, Hollenbach JA. Consumer (dis-) interest in genetic ancestry testing: the roles of race, immigration, and ancestral certainty. New Genetics and Society. 2019;38(2):165–194. doi: 10.1080/14636778.2018.1562327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonassaint CR, Santos ER, Glover CM, Payne PW, Fasaye G-A, Oji-Njideka N, Hooker S, Hernandez W, Foster MW, Kittles RA, Royal CD. Regional differences in awareness and attitudes regarding genetic testing for disease risk and ancestry. Hum Genet. 2010;128(3):249–260. doi: 10.1007/s00439-010-0845-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengst ET. FACE facts: why human genetics will always provoke bioethics. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2004;32(2):267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2004.tb00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khandaker T. (2018). Canada is using ancestry DNA websites to help deport people. Vice News

- Kirkpatrick BE, Rashkin MD. Ancestry testing and the practice of genetic counseling. J Genet Couns. 2017;26(1):6–20. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-0014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimentidis YC, Miller GF, Shriver MD. Genetic admixture, self-reported ethnicity, self-estimated admixture, and skin pigmentation among Hispanics and Native Americans. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 2009;138(4):375–383. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton B, Foeman A. Shifting winds: using ancestry DNA to explore multiracial individuals’ patterns of articulating racial identity. Identity. 2017;17(2):69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS-J, Bolnick DA, Duster T, Ossorio P, TallBear K. The illusive gold standard in genetic ancestry testing. Science. 2009;325(5936):38–39. doi: 10.1126/science.1173038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libiger O, Schork NJ. A method for inferring an individual’s genetic ancestry and degree of admixture associated with six major continental populations. Front Genet. 2013;3:322. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone FB. Anthropological implications of sickle cell gene distribution in West Africa 1. Am Anthropol. 1958;60(3):533–562. [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur D. 23andMe raises prices, splits its health and ancestry analyses. 2009

- Mainous AG, 3rd, Johnson SP, Chirina S, Baker R. Academic family physicians’ perception of genetic testing and integration into practice: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2013;45(4):257–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks J. Genetic testing: when is information too much? Anthropol Today. 2018;34(2):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall E. Human genome 10th anniversary. Waiting for the revolution. Science. 2011;331(6017):526–529. doi: 10.1126/science.331.6017.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I. Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires. USA: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]