Abstract

Background

Despite the potential benefits of parents-adolescent relationships on suicidal behaviours among adolescents, research on these topics are importantly limited by lack of comprehensiveness, difficulties in cross-country comparisons, and limited generalisability, among others. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours by sex and region, and to investigate their associations.

Methods

We used data from the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS) from 52 countries in 2009–2015 for 120 858 adolescents (53.9% girls) aged 12–15 years. Using meta-analysis with random effects, we estimated the prevalence of parents-adolescent relationships (i.e. understanding problems, monitoring academic and leisure time activities, and respecting privacy) and suicidal behaviours (i.e. suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempt). Multi-level mixed-effect logistic regressions were used to investigate their associations.

Findings

Overall, boys and girls reported similar levels of parental understanding of problems (35.8% vs. 36.8%), monitoring academic activities (41.8% vs. 41.1%), and respecting privacy (69.6% vs. 69.7%), whereas girls reported higher level of parental monitoring of leisure time activities than boys (44.9% vs. 40.0%). Adolescents in the Western Pacific region reported the lowest level of parental understanding of problems and monitoring activities, while those in South-East Asia region least reported that their parents respected their privacy. The overall prevalence of any suicidal behaviour was higher in girls than boys (26.2% vs. 23.0%). Suicidal behaviour was less likely in adolescents if their parents understood their problems (odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals: 0.70, 0.68–0.73), monitored their academic (0.81, 0.78–0.84) and leisure time activities (0.73, 0.71–0.75), and respected their privacy (0.83, 0.80–0.86). There was evidence of heterogeneity in those associations by sex and regions.

Interpretations

Although the prevalence of parents-adolescent relationships and adolescent suicidal behaviours varied particularly by sex and region, there were strong and independent associations among them.

Keywords: Suicidal behaviours, Suicidal ideation, Parental support, Parental monitoring, Adolescents

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We identified publications that examined the associations between parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours in adolescents through searching in PubMed and Web of Science using combinations of relevant search terms (e.g. parent*, adolescent*, young adult, suicid*, association) until 31 July 2020 and also through identifying relevant citations from the reference lists of those included paper. We identified several papers, based on the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) data, comparing prevalence of suicidal behaviours in adolescents regionally and globally. However, we did not find any study that provided global and regional comparisons of various aspects of relationship between parents and adolescents. The evidence on the potential benefits of parents-adolescent relationships on suicidal behaviours in adolescents was concentrated in high-income countries.

Added value of this study

Our study is the first study to provide sex-specific estimates for various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships according to country, WHO regions, and the World Bank country income classifications. With marked variations existed across countries and regions, we found that nearly one-third of the adolescents aged 12–15 years reported that their parents understood problems and monitored their academic and leisure time activities, whereas about two-thirds reported that their parents respected their privacy. Consistent with findings from previous studies, we also found that girls were more likely to have suicidal behaviours than boys. All four variables representing parents-adolescent relationships were strongly and separately associated with lower odds of suicidal behaviours, from ideation to attempt.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study suggests that the prevalence of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours varies markedly across countries and regions, yet parental factors like understanding problems, monitoring activities (both academic and leisure time), and respecting privacy have strong and consistent protective effects on adolescents’ suicidal behaviours. These findings guide adolescent suicide prevention programmes and strategies to focus more on family interventions.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

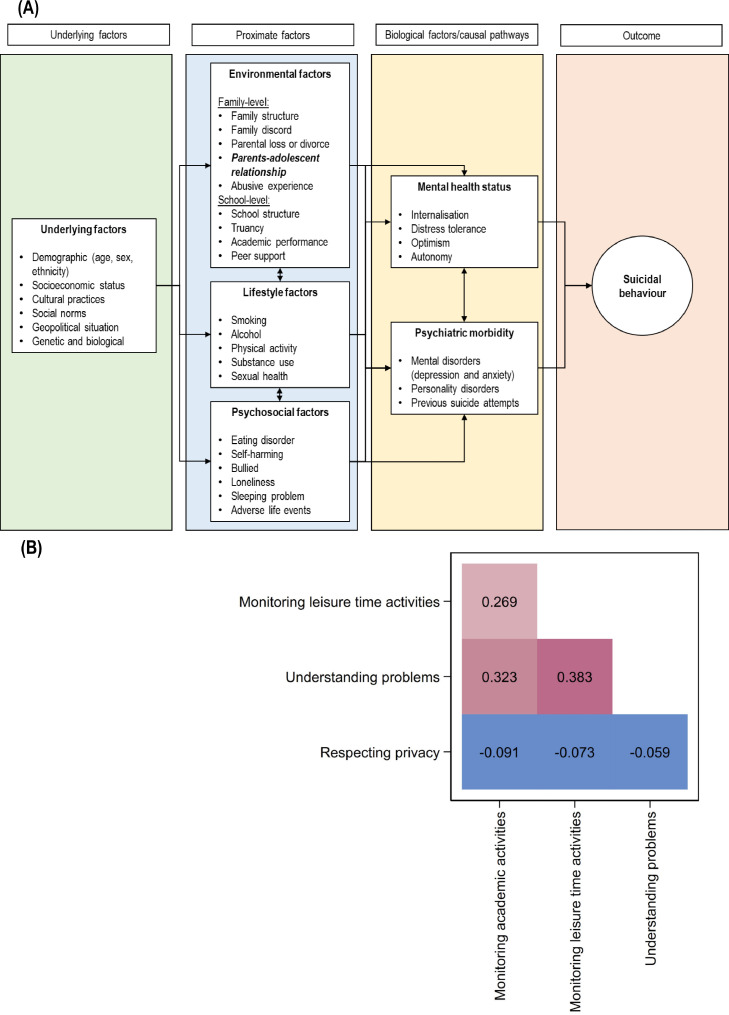

Suicidal behaviours among adolescents has become a major public health concern worldwide, particularly because it is an important precursor of subsequent suicide [1]. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents aged 10–24 years, accounting for an estimated 67,000 adolescent deaths each year [2]. Suicidal behaviour includes several stages: suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempt [3]. Recent studies reported that globally nearly one in six adolescents aged 12–15 years had reported that they either thought about committing suicide, made suicide plan, or attempted suicide in the preceding 12 months [[4], [5], [6]]. While suicidal behaviours are predictors of future suicide, they can also lead to traumatic experiences and other psychological issues [6,7]. Various psychological, social, and environmental factors as well as complex interactions among them can increase the risks of suicidal behaviour in adolescents (Fig. 1A) [1,3,[7], [8], [9], [10]].

Fig. 1.

(A) Conceptual framework outlining various factors for suicidal behaviour among adolescents; (B) Correlation matrix for four parents-adolescent relationship variables.

Pearson coefficients were used to estimate the correlation among parents-adolescent relationship variables.

Parents-adolescent relationship is a broad concept because it can encompass several dimensions, such as emotional support, monitoring, supervision, conflict, and privacy. Parents roles in each of these dimensions can significantly contribute to adolescents’ social, emotional, and mental development, including adoption of effective coping strategies to stress and adverse life events [1]. While adolescents who are either exposed to family conflicts (for example, parental divorce or separation) or report low levels of perceived parental support are more likely to develop suicidal behaviours [1,11–16]. On the other hand, there is evidence suggesting that positive relationships between parents and adolescents can reduce the risks of depression and anxiety (often the precursors of suicidal behaviour) in adolescents [1]. Furthermore, various dimensions of parents-adolescent relationship can impact adolescents’ mental health status differently depending on the underlying sociocultural practices and norms [4,16,17]. Therefore, it is necessary to disentangle the effects of various dimensions of parents-adolescent relationship on the risks of suicidal behaviour among adolescents living in various settings.

Despite the potential benefits of parents-adolescent relationships on suicidal behaviours among adolescents, the current evidence base is importantly limited by one or more of the following: i) lack of comprehensive assessment of various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships; ii) it is unclear whether different aspects of parents-adolescent relationships impact adolescents’ suicidal behaviours differently and whether other factors like sex and low socioeconomic status modify such relationships; iii) evidence mostly coming from high-income countries [9,10,12,18] and paucity of information from low-income and middle-income countries where more than three-quarters of global suicide occurs [2]; iv) difficulties in making cross-country comparisons because of differences in variable definitions and measures, study populations, and analytical approaches; and v) small studies based on clinical and community samples limiting generalisability of findings. Therefore, a large-scale epidemiological investigation is urgently needed to understand the associations reliably and comprehensively between parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours to help shape adolescent suicide prevention strategies.

To address these limitations, we investigated the associations between parent-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviour using country-representative samples from the Global School-based Health Survey (GSHS) in 52 countries that vary in WHO regions and World Bank country income groupings [19]. GSHS has been conducted in a number of resource-poor countries to provide comparable data on various health behaviours and factors in school-going adolescents [20]. Our key aims were to: i) quantify the country-level prevalence estimates for various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours; ii) compare these estimates by sex, WHO regions, and World Bank country income classifications; iii) investigate the associations between various aspects of parent-adolescent relationships and different forms of suicidal behaviour; and iv) assessing any possible differences in those associations by sex or other factors.

Methods

2.1. Data sources

This study was based on secondary analysis of GSHS datasets from 52 countries conducted between 2009 and 2016 [20]. Surveys conducted before 2009 were excluded because questions asked on our variables of interest were different or absent in those surveys. In cases where more than one surveys were conducted for a country within this time period, we included the latest survey.

Details about GSHS surveys’ purpose and methodology have been described elsewhere [21] and are summarised here. All GSHS surveys are conducted by World Health Organisation (WHO) and the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in collaboration with UNICEF, UNESCO, and UNAIDS to understand health behaviours and protective factors among school students. These surveys select country-representative samples of young adolescents based on a two-staged cluster sampling process. In the first stage, using a probability-proportionate-to-size (PPS) method, schools are randomly selected from the list of all schools in the country. In the second stage, classrooms with students of target age group are randomly selected and all students in those classrooms are asked to participate in the survey [21]. The age range of participating adolescents varied across countries, but most countries had data for adolescents aged 12–15 years; therefore, we restricted our analysis to this age group.

The GSHS surveys use a validated questionnaire (often translated into an appropriate language) with specific modules to collect information on various factors, including modules on mental health and experiences at home. The survey questionnaire is self-administered during one regular class period. Data from GSHS surveys are entered at the CDC using automatic optic character recognition [21].

Ethical approvals were taken for all GSHS surveys from a national government administrative body and from an institutional review board or ethics committee. Informed consent was obtained from participating students, their parents, and school authorities, as appropriate [21]. The publicly accessible data used in this study were anonymized for protection of privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality.

2.2. Variable definitions

The definitions, questions, and coding methods for the exposure and outcome variables are shown in the Appendix1p2. Parents-adolescent relationship was captured by four variables in GSHS surveys: understanding problems, monitoring academic activities, monitoring leisure time activities, and respecting privacy. For these variables, participants were asked relevant questions with the following responses: “never”, “rarely”, “sometimes”, “most of the time”, and “always”. Depending on how the questions were formulated, these responses were dichotomised for analysis - understanding problems, monitoring academic activities, and monitoring leisure time activities were defined as “most of the time” or “always”, whereas respecting privacy was defined as “never’ or “rarely”. The correlation matrix for these four variables suggests that each of them represents a different aspect of parents-adolescent relationship (Fig. 1B).

The outcome, suicidal behaviour, was assessed based on three variables: suicidal ideation, suicide planning and suicide attempt during the past 12 months. The questions about suicidal ideation and suicide planning were asked as “yes/no” questions, whereas the question on suicide attempt had possible answers of 0, 1, 2 or 3, 4 or 5, 6 or more times. The responses to suicide attempt were then dichotomised for analysis: no = 0 time and yes = 1, 2 or 3, 4 or 5, 6 or more times (Appendix1p2). For further analysis, we also created a composite variable named “any suicidal behaviour” for those who responded ‘yes’ to either suicidal ideation, suicide planning, or suicide attempt.

Other variables used in this study include age, sex, grade, proxy for low socioeconomic status, survey year, country income classification, loneliness, sleeping problem, peer support, bullied, truancy, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and overweight. The proxy for low socioeconomic status was food insecurity, as assessed by the question “During the past 30 days, how often did you go hungry because there was not enough food in your home?” Those who responded ‘most of the time or always’ were considered to come from low socioeconomic status [5]. Country income classification was based on 2018 gross national income (GNI) per capita according to the World Bank list of economies by income group [19]. Sleeping problem was assessed by the question “During the past 12 months, how often have you been so worried about something that you could not sleep at night?” with anxiety defined as “most of the time” or “always”. Loneliness was measured by the question “During the past 12 months, how often have you felt lonely?” with loneliness defined as “most of the time” or “always”. Peer support was assessed by the question “During the past 30 days, how often were most of the students in your school kind and helpful?”, and those who responded “most of the time” or “always” were classified as having peer support. Bullied was assessed by the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days were you bullied?” Truancy was defined if an adolescent missed their classes or school without permission in the past 30 days. Cigarette smoking was defined as smoking on at least one day in the past 30 days, whereas alcohol drinking was defined as having at least one glass of wine, a bottle of beer, a small glass of liquor, or a mixed drink. According to the WHO Growth Reference Data, [22] adolescents were categorised as overweight if their BMI was more than +1SD from the median for age and sex.

2.3. Statistical analysis

We followed the data analysis instructions provided by CDC [21], and used a weight variable, a stratification variable and a primary sampling using (PSU) variable in the “SVYSET” programme in Stata (version 16.0) to account for the complex sampling design of survey data. We calculated country-specific weighted prevalence with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for parents-adolescent relationship variables and suicidal behaviour variables according to sex. To calculate the pooled regional, country income group-specific, and overall prevalence estimates for these factors, we performed random-effects meta-analysis in Stata because there was significant heterogeneity in prevalence estimates between countries (I2 >95%).

We used multilevel mixed-effect logistic regressions (to deal with common cluster-level random effects within country) to estimate odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs for the associations between parents-adolescent relationship and suicidal behaviours, with adjustment of various the individual, country and WHO region level variables. We assessed the individual effects of adjustment for each of the demographic (age, sex, low socioeconomic status), psychosocial (loneliness, sleeping problem, peer support, bullied, truancy), and lifestyle (smoking, alcohol drinking, overweight), and then all of them together for all associations. We also examined whether the parents-adolescent relationship variables were associated with any suicidal behaviour, independent of each other. We also explored any further potential for effect modification by various factors for the associations between parents-adolescent relationship and suicidal behaviour by comparing ORs across subgroups of other factors. In subgroup analysis, heterogeneity was tested by likelihood ratio tests comparing models with and without cross product interaction term.

Participants who had valid information on the exposure and outcome variables were included in the analysis. Missing or non-applicable values for covariables (< 1% for all except for smoking [7%] and alcohol [15%]) were treated as a separate category. Where we present results in figures, the prevalence and OR estimates are represented by squares, and their corresponding 95% CIs are represented by lines. The area of each square is inversely proportional to the variance of the logarithm of the corresponding estimates, which shows the amount of statistical information involved with the estimates. Statistical significance was set at a two tailed p<0.05.

2.4. Role of the funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Results

We included GSHS datasets from 52 countries with 120 858 adolescents (53.9% girls) aged 12–15 years in this analysis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included GHSH survey and the participants. The included surveys were from countries from five WHO regions: eight from African Region, 15 from the Region of Americas, seven from Eastern Mediterranean Region, six from South-East Asia Region and 16 from Western Pacific Region. According to the World Bank country income classification, included surveys were from six low income countries, 17 lower middle-income countries, 16 upper middle-income countries, 11 high income countries and two countries with no classification information. The median sample size per country was 1395 (IQR: 1103–2157). We included adolescents with complete data on parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours (90.2% of the total sample) in our analysis.

Table 1.

Survey characteristics, by country.

| Country | Survey year | Country income group | n/N | Analysis sample (%) | Boys, n (%) | Girls, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Region | ||||||

| Benin | 2016 | L | 691/717 | 96.4 | 308 (44.6) | 383 (55.4) |

| Eswatini | 2013 | LM | 1155/1318 | 87.6 | 431 (37.3) | 724 (62.7) |

| Ghana | 2012 | LM | 975/1110 | 87.8 | 492 (50.5) | 483 (49.5) |

| Mauritania | 2010 | LM | 1120/1285 | 87.2 | 510 (45.5) | 610 (54.5) |

| Mozambique | 2015 | L | 547/668 | 81.9 | 269 (49.2) | 278 (50.8) |

| Namibia | 2013 | UM | 1740/1936 | 89.9 | 714 (41.0) | 1026 (59.0) |

| Seychelles | 2015 | H | 1747/2061 | 84.8 | 769 (44.0) | 978 (56.0) |

| Tanzania | 2014 | L | 2397/2615 | 91.7 | 1061 (44.3) | 1336 (55.7) |

| Region of the Americas | ||||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 2009 | H | 1057/1235 | 85.6 | 483 (45.7) | 574 (54.3) |

| Argentina | 2012 | UM | 18,999/21,528 | 88.3 | 8808 (46.4) | 10,191 (53.6) |

| Bahamas | 2013 | H | 1148/1308 | 87.8 | 507 (44.2) | 641 (55.8) |

| Belize | 2011 | UM | 1428/1600 | 89.3 | 664 (46.5) | 764 (53.5) |

| Bolivia | 2012 | LM | 2562/2804 | 91.4 | 1271 (49.6) | 1291 (50.4) |

| British Virgin Islands | 2009 | H | 1076/1195 | 90.0 | 470 (43.7) | 606 (56.3) |

| Costa Rica | 2009 | UM | 2166/2265 | 95.6 | 1028 (47.5) | 1138 (52.5) |

| Curacao | 2015 | H | 1266/1498 | 84.5 | 578 (45.7) | 688 (54.3) |

| El Salvador | 2013 | LM | 1482/1615 | 91.8 | 782 (52.8) | 700 (47.2) |

| Honduras | 2012 | LM | 1364/1486 | 91.8 | 650 (47.7) | 714 (52.3) |

| Jamaica | 2010 | UM | 1042/1204 | 86.5 | 490 (47.0) | 552 (53.0) |

| Peru | 2010 | UM | 2261/2359 | 95.8 | 1086 (48.0) | 1175 (52.0) |

| Saint Kitts Nevis | 2011 | H | 1305/1471 | 88.7 | 548 (42.0) | 757 (58.0) |

| Suriname | 2009 | UM | 958/1046 | 91.6 | 441 (46.0) | 517 (54.0) |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2011 | H | 2122/2363 | 89.8 | 1142 (53.8) | 980 (46.2) |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | ||||||

| Afghanistan | 2014 | L | 1120/1493 | 75.0 | 423 (37.8) | 697 (62.2) |

| Iraq | 2012 | UM | 1355/1533 | 88.4 | 741 (54.7) | 614 (45.3) |

| Kuwait | 2015 | H | 1678/2034 | 82.5 | 760 (45.3) | 918 (54.7) |

| Lebanon | 2011 | UM | 1770/1982 | 89.3 | 816 (46.1) | 954 (53.9) |

| Morocco | 2010 | LM | 2184/2405 | 90.8 | 1101 (50.4) | 1083 (49.6) |

| UAE | 2010 | H | 2078/2302 | 90.3 | 791 (38.1) | 1287 (61.9) |

| Yemen | 2014 | L | 1324/1553 | 85.3 | 677 (51.1) | 647 (48.9) |

| South-East Asia Region | ||||||

| Bangladesh | 2014 | LM | 2545/2753 | 92.4 | 967 (38.0) | 1578 (62.0) |

| Indonesia | 2015 | LM | 8290/8806 | 94.1 | 3770 (45.5) | 4520 (54.5) |

| Maldives | 2014 | UM | 1496/1781 | 84.0 | 584 (39.0) | 912 (61.0) |

| Nepal | 2015 | L | 4192/4616 | 90.8 | 1906 (45.5) | 2286 (54.5) |

| Thailand | 2015 | UM | 3582/4132 | 86.7 | 1585 (44.2) | 1997 (55.8) |

| Timor-Leste | 2015 | LM | 1419/1631 | 87.0 | 581 (40.9) | 838 (59.1) |

| Western Pacific Region | ||||||

| Brunei | 2014 | H | 1728/1824 | 94.7 | 803 (46.5) | 925 (53.5) |

| Cook Islands | 2015 | NA | 350/366 | 95.6 | 170 (48.6) | 180 (51.4) |

| Fiji | 2016 | UM | 1303/1537 | 84.8 | 610 (46.8) | 693 (53.2) |

| French Polynesia | 2015 | H | 1732/1902 | 91.1 | 825 (47.6) | 907 (52.4) |

| Kiribati | 2011 | LM | 1253/1340 | 93.5 | 512 (40.9) | 741 (59.1) |

| Laos | 2015 | LM | 1609/1644 | 97.9 | 676 (42.0) | 933 (58.0) |

| Malaysia | 2012 | UM | 15,680/16,273 | 96.4 | 7946 (50.7) | 7734 (49.3) |

| Mongolia | 2013 | LM | 3520/3707 | 95.0 | 1677 (47.6) | 1843 (52.4) |

| Niue | 2010 | LM | 73/82 | 89.0 | 43 (58.9) | 30 (41.1) |

| Philippines | 2015 | LM | 5836/6162 | 94.7 | 2513 (43.1) | 3323 (56.9) |

| Samoa | 2011 | UM | 1259/2200 | 57.2 | 428 (34.0) | 831 (66.0) |

| Solomon Islands | 2011 | LM | 799/925 | 86.4 | 401 (50.2) | 398 (49.8) |

| Tokelau | 2014 | UM | 75/85 | 88.2 | 40 (53.3) | 35 (46.7) |

| Tuvalu | 2013 | UM | 598/679 | 88.1 | 277 (46.3) | 321 (53.7) |

| Vanuatu | 2011 | LM | 798/852 | 93.7 | 332 (41.6) | 466 (58.4) |

| Wallis Futuna | 2015 | NA | 604/718 | 84.1 | 277 (45.9) | 327 (54.1) |

| Total | 120,858/134,004 | 90.2 | 55,734 (46.1) | 65,124 (53.9) | ||

n=number of participants who had valid information on physical fight, physical attack and suicidal behaviour, and included in this analysis; N=total number of participants aged 12–15 years included in the GSHS.

Based on World Bank country income groups according to 2018 gross national income (GNI) per capita.19 L = low income, LM = lower middle income, UM = upper middle income, H = high income, NA = not available.

3.1. Estimates for parents-adolescent relationships

Overall, around one-third of the adolescents had parents who understood their problems, with girls reporting slightly higher than boys (36.8% vs. 35.8%) (Table 2). Less than half of adolescents reported that their parents monitored their academic and leisure time activities. Although there was no difference for monitoring academic activities between boys and girls, parents of boys were less likely to monitor leisure time activities compared to parents of girls (40.0% vs. 44.9%). More than two-third of the parents respected privacy of the adolescents and there was no difference between boys and girls (69.6% vs. 69.7%). The Western Pacific region, for both boys and girls, had the lowest proportions for parents who understood their children's problems and monitored their academic and leisure time activities. The level of respecting privacy was the lowest in the South-East Asia region (boys: 66.1% and girls: 66.0%). According to the country income classification, adolescent boys and girls from the lower middle-income countries, compared to adolescents from other countries, were less likely to have parents who understood their problems and who were aware of their leisure time activities (appendix p3). At country level, the proportions of adolescent boys who reported that their parents understood their problems ranged from 8.1% in Timor-Leste to 58.7% in Curacao, while for adolescent girls the proportion ranged from 8.6% in Timor-Leste to 60.8% in Afghanistan. Adolescent boys from Brunei (15.9%) and Belize (59.0%) respectively had the lowest and highest level of parental monitoring of academic activities, while Malaysia (15.3%) and Fiji (62.2%) had the lowest and highest proportions for girls. Adolescents (both boys and girls) from Timor-Leste had the lowest prevalence (18.2% and 19.7%) of parental monitoring of leisure time activities while adolescents from Curacao had the highest prevalence (65.4% and 69.9%). The proportion of parents who respected adolescents’ privacy ranged from 38.4% in Solomon Islands to 92.5% in Laos for boys, and from 42.2% in Solomon Islands to 92.2% in Tuvalu for girls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Country and region-specific prevalence of various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships, by sex.

| Prevalence (%) with 95% CIs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||||||

| Understanding problems | Monitoring academic activities | Monitoring leisure time activities | Respecting privacy | Understanding problems | Monitoring academic activities | Monitoring leisure time activities | Respecting privacy | |

| African Region | ||||||||

| Benin | 36.7 (31.3–42.3) | 42.2 (36.6–47.9) | 32.5 (27.3–38.0) | 83.1 (78.5–87.1) | 39.4 (34.5–44.5) | 43.6 (38.6–48.7) | 44.9 (39.9–50.0) | 76.2 (71.7–80.4) |

| Eswatini | 43.6 (38.9–48.4) | 39.4 (34.8–44.2) | 30.9 (26.5–35.5) | 65.2 (60.5–69.7) | 49.7 (46.0–53.4) | 45.3 (41.6–49.0) | 41.0 (37.4–44.7) | 56.6 (52.9–60.3) |

| Ghana | 33.7 (29.6–38.1) | 43.5 (39.1–48.0) | 33.5 (29.4–37.9) | 59.1 (54.7–63.5) | 32.1 (27.9–36.5) | 43.5 (39.0–48.0) | 39.1 (34.8–43.6) | 57.3 (52.8–61.8) |

| Mauritania | 36.1 (31.9–40.4) | 52.2 (47.7–56.6) | 33.7 (29.6–38.0) | 64.7 (60.4–68.9) | 32.8 (29.1–36.7) | 47.7 (43.7–51.8) | 36.6 (32.7–40.5) | 69.5 (65.7–73.1) |

| Mozambique | 52.0 (45.9–58.1) | 52.8 (46.6–58.9) | 39.0 (33.2–45.1) | 82.5 (77.5–86.9) | 48.9 (42.9–55.0) | 56.1 (50.1–62.0) | 47.5 (41.5–53.5) | 79.5 (74.3–84.1) |

| Namibia | 39.1 (35.5–42.8) | 45.2 (41.5–49.0) | 35.4 (31.9–39.1) | 57.0 (53.3–60.7) | 42.8 (39.7–45.9) | 46.3 (43.2–49.4) | 40.3 (37.2–43.3) | 56.6 (53.5–59.7) |

| Seychelles | 30.8 (27.6–34.2) | 43.0 (39.5–46.6) | 35.6 (32.2–39.1) | 68.4 (65.0–71.7) | 32.7 (29.8–35.8) | 45.9 (42.8–49.1) | 43.3 (40.1–46.4) | 67.9 (64.9–70.8) |

| Tanzania | 36.7 (33.8–39.6) | 56.1 (53.0–59.1) | 34.9 (32.0–37.8) | 77.9 (75.3–80.4) | 39.7 (37.1–42.4) | 61.8 (59.2–64.4) | 42.4 (39.8–45.1) | 75.4 (73.0–77.7) |

| Pooled estimates | 38.3 (34.5–42.1) | 46.8 (42.3–51.3) | 34.5 (33.1–35.9) | 69.8 (62.9–76.6) | 39.7 (35.1–44.2) | 48.8 (43.4–54.1) | 41.6 (39.6–43.5) | 67.4 (61.1–73.7) |

| Regions of the Americas | ||||||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 32.1 (27.9–36.5) | 38.1 (33.7–42.6) | 35.6 (31.3–40.1) | 58.4 (53.8–62.8) | 34.3 (30.4–38.4) | 36.1 (32.1–40.1) | 45.5 (41.3–49.6) | 63.9 (59.9–67.9) |

| Argentina | 48.1 (47.0–49.1) | 34.4 (33.4–35.4) | 51.0 (50.0–52.1) | 70.1 (69.1–71.0) | 50.8 (49.8–51.8) | 30.0 (29.1–30.9) | 59.1 (58.1–60.0) | 66.0 (65.1–66.9) |

| Bahamas | 37.9 (33.6–42.3) | 48.1 (43.7–52.6) | 46.2 (41.7–50.6) | 66.1 (61.8–70.2) | 36.3 (32.6–40.2) | 51.0 (47.1–54.9) | 47.3 (43.3–51.2) | 62.9 (59.0–66.6) |

| Belize | 52.7 (48.8–56.6) | 59.0 (55.2–62.8) | 56.3 (52.5–60.1) | 61.4 (57.6–65.2) | 47.3 (43.7–50.9) | 56.0 (52.4–59.6) | 55.6 (52.0–59.2) | 58.0 (54.4–61.5) |

| Bolivia | 31.6 (29.1–34.3) | 40.9 (38.2–43.7) | 36.5 (33.9–39.2) | 80.2 (77.9–82.3) | 33.5 (30.9–36.1) | 42.9 (40.2–45.7) | 41.2 (38.5–43.9) | 78.2 (75.9–80.5) |

| British Virgin Islands | 43.6 (39.1–48.2) | 40.4 (36.0–45.0) | 41.7 (37.2–46.3) | 64.9 (60.4–69.2) | 38.8 (34.9–42.8) | 38.8 (34.9–42.8) | 55.9 (51.9–59.9) | 67.8 (63.9–71.5) |

| Costa Rica | 45.9 (42.8–49.0) | 39.0 (36.0–42.1) | 52.2 (49.1–55.3) | 83.5 (81.0–85.7) | 48.5 (45.6–51.5) | 33.7 (30.9–36.5) | 56.7 (53.7–59.6) | 79.7 (77.2–82.0) |

| Curacao | 58.7 (54.5–62.7) | 49.0 (44.8–53.1) | 65.4 (61.4–69.3) | 77.2 (73.5–80.5) | 58.3 (54.5–62.0) | 38.1 (34.4–41.8) | 69.9 (66.3–73.3) | 77.8 (74.5–80.8) |

| El Salvador | 54.0 (50.4–57.5) | 56.5 (53.0–60.0) | 58.2 (54.6–61.7) | 76.1 (72.9–79.0) | 48.6 (44.8–52.3) | 58.4 (54.7–62.1) | 60.0 (56.3–63.7) | 76.0 (72.7–79.1) |

| Honduras | 50.6 (46.7–54.5) | 57.1 (53.2–60.9) | 58.5 (54.6–62.3) | 83.5 (80.5–86.3) | 45.8 (42.1–49.5) | 52.4 (48.6–56.1) | 56.4 (52.7–60.1) | 79.4 (76.3–82.3) |

| Jamaica | 31.8 (27.7–36.2) | 39.0 (34.6–43.5) | 39.0 (34.6–43.5) | 57.1 (52.6–61.6) | 31.2 (27.3–35.2) | 42.4 (38.2–46.6) | 42.6 (38.4–46.8) | 52.2 (47.9–56.4) |

| Peru | 33.6 (30.8–36.5) | 43.6 (40.7–46.7) | 33.5 (30.7–36.4) | 80.7 (78.2–83.0) | 38.4 (35.6–41.2) | 45.6 (42.7–48.5) | 40.6 (37.8–43.5) | 78.7 (76.3–81.0) |

| Saint Kitts Nevis | 26.6 (23.0–30.6) | 33.0 (29.1–37.1) | 31.2 (27.3–35.3) | 62.2 (58.0–66.3) | 26.2 (23.1–29.4) | 24.8 (21.8–28.1) | 35.9 (32.5–39.5) | 64.7 (61.2–68.1) |

| Suriname | 45.4 (40.6–50.1) | 43.3 (38.6–48.1) | 49.4 (44.7–54.2) | 71.2 (66.7–75.4) | 44.1 (39.8–48.5) | 37.1 (33.0–41.5) | 56.9 (52.5–61.2) | 68.3 (64.1–72.3) |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 41.2 (38.3–44.1) | 50.2 (47.2–53.1) | 49.7 (46.8–52.7) | 56.1 (53.2–59.0) | 41.1 (38.0–44.3) | 45.7 (42.6–48.9) | 52.6 (49.4–55.7) | 56.7 (53.6–59.9) |

| Pooled estimates | 42.2 (37.7–46.8) | 44.8 (40.2–49.4) | 47.0 (42.3–51.6) | 70.0 (65.6–74.4) | 41.5 (36.9–46.2) | 42.2 (36.9–47.5) | 51.8 (47.1–56.4) | 68.8 (64.6–72.9) |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | ||||||||

| Afghanistan | 50.4 (45.5–55.2) | 43.5 (38.7–48.4) | 53.7 (48.8–58.5) | 61.7 (56.9–66.4) | 60.8 (57.1–64.5) | 53.4 (49.6–57.1) | 61.5 (57.8–65.2) | 61.7 (58.0–65.3) |

| Iraq | 47.1 (43.5–50.8) | 54.1 (50.5–57.7) | 47.6 (44.0–51.3) | 85.8 (83.1–88.3) | 42.0 (38.1–46.0) | 46.6 (42.6–50.6) | 46.7 (42.7–50.8) | 89.6 (86.9–91.9) |

| Kuwait | 35.5 (32.1–39.0) | 49.3 (45.7–53.0) | 48.8 (45.2–52.4) | 68.9 (65.5–72.2) | 32.0 (29.0–35.2) | 32.5 (29.4–35.6) | 45.6 (42.4–48.9) | 69.5 (66.4–72.5) |

| Lebanon | 47.9 (44.4–51.4) | 49.9 (46.4–53.4) | 51.5 (48.0–55.0) | 78.4 (75.4–81.2) | 50.1 (46.9–53.3) | 42.9 (39.7–46.1) | 57.1 (53.9–60.3) | 85.8 (83.5–88.0) |

| Morocco | 25.9 (23.3–28.6) | 44.5 (41.5–47.5) | 38.1 (35.3–41.1) | 74.2 (71.5–76.8) | 31.9 (29.2–34.8) | 50.2 (47.2–53.3) | 44.0 (41.0–47.0) | 77.4 (74.8–79.8) |

| UAE | 46.8 (43.3–50.3) | 54.4 (50.8–57.9) | 48.0 (44.5–51.6) | 78.3 (75.2–81.1) | 48.3 (45.5–51.0) | 40.2 (37.5–42.9) | 52.6 (49.8–55.4) | 80.9 (78.6–83.0) |

| Yemen | 20.4 (17.4–23.6) | 39.7 (36.0–43.5) | 28.2 (24.9–31.8) | 74.0 (70.5–77.3) | 24.3 (21.0–27.8) | 40.6 (36.8–44.5) | 25.7 (22.3–29.2) | 81.3 (78.1–84.2) |

| Pooled estimates | 39.1 (29.9–48.3) | 48.0 (43.9–52.0) | 45.1 (38.5–51.7) | 74.6 (69.5–79.8) | 41.3 (32.2–50.4) | 43.7 (38.5–49.0) | 47.6 (39.3–55.9) | 78.1 (71.9–84.3) |

| South-East Asia Region | ||||||||

| Bangladesh | 42.7 (39.6–45.9) | 52.9 (49.7–56.1) | 41.5 (38.3–44.6) | 84.9 (82.5–87.1) | 55.3 (52.8–57.8) | 56.6 (54.1–59.1) | 49.1 (46.6–51.6) | 88.9 (87.3–90.4) |

| Indonesia | 32.4 (30.9–33.9) | 39.9 (38.3–41.5) | 29.8 (28.4–31.3) | 56.5 (54.9–58.1) | 37.7 (36.3–39.2) | 38.6 (37.1–40.0) | 47.2 (45.8–48.7) | 57.0 (55.5–58.4) |

| Maldives | 37.2 (33.2–41.2) | 38.0 (34.1–42.1) | 51.5 (47.4–55.7) | 65.9 (61.9–69.8) | 33.6 (30.5–36.7) | 27.7 (24.9–30.8) | 47.6 (44.3–50.9) | 63.9 (60.7–67.0) |

| Nepal | 52.6 (50.3–54.8) | 48.0 (45.7–50.3) | 46.4 (44.1–48.6) | 43.4 (41.1–45.6) | 57.2 (55.1–59.2) | 52.9 (50.9–55.0) | 56.3 (54.3–58.4) | 45.1 (43.0–47.2) |

| Thailand | 25.9 (23.7–28.1) | 31.9 (29.6–34.3) | 35.3 (33.0–37.7) | 68.5 (66.1–70.7) | 30.3 (28.3–32.4) | 33.8 (31.7–35.9) | 47.8 (45.6–50.0) | 62.7 (60.5–64.8) |

| Timor-Leste | 8.1 (6.0–10.6) | 31.3 (27.6–35.3) | 18.2 (15.2–21.6) | 77.3 (73.7–80.6) | 8.6 (6.8–10.7) | 29.5 (26.4–32.7) | 19.7 (17.0–22.5) | 78.2 (75.2–80.9) |

| Pooled estimates | 33.1 (20.9–45.3) | 40.4 (34.1–46.6) | 37.1 (28.8–45.3) | 66.1 (53.7–78.4) | 37.1 (22.8–51.4) | 39.9 (31.2–48.6) | 44.7 (35.9–53.4) | 66.0 (51.9–80.0) |

| Western Pacific Region | ||||||||

| Brunei | 31.9 (28.7–35.2) | 15.9 (13.5–18.7) | 43.6 (40.1–47.1) | 65.3 (61.8–68.5) | 26.1 (23.3–29.0) | 17.1 (14.7–19.7) | 41.0 (37.8–44.2) | 65.1 (61.9–68.2) |

| Cook Islands | 28.2 (21.6–35.6) | 32.9 (25.9–40.6) | 31.8 (24.8–39.3) | 66.5 (58.8–73.5) | 23.3 (17.4–30.2) | 32.2 (25.5–39.6) | 39.4 (32.3–47.0) | 63.3 (55.8–70.4) |

| Fiji | 45.1 (41.1–49.1) | 55.9 (51.9–59.9) | 45.9 (41.9–49.9) | 52.3 (48.2–56.3) | 53.7 (49.9–57.4) | 62.2 (58.5–65.8) | 57.6 (53.8–61.3) | 51.4 (47.6–55.2) |

| French Polynesia | 38.5 (35.2–42.0) | 41.0 (37.6–44.4) | 60.0 (56.6–63.4) | 81.6 (78.8–84.2) | 40.9 (37.7–44.2) | 38.7 (35.5–42.0) | 55.1 (51.8–58.4) | 82.7 (80.1–85.1) |

| Kiribati | 14.5 (11.5–17.8) | 20.3 (16.9–24.1) | 23.2 (19.6–27.1) | 61.5 (57.2–65.8) | 15.7 (13.1–18.5) | 25.5 (22.4–28.8) | 29.4 (26.2–32.8) | 65.9 (62.3–69.3) |

| Laos | 18.5 (15.6–21.6) | 25.1 (21.9–28.6) | 31.8 (28.3–35.5) | 92.5 (90.2–94.3) | 16.4 (14.1–18.9) | 18.9 (16.4–21.5) | 32.8 (29.8–35.9) | 89.8 (87.7–91.7) |

| Malaysia | 32.4 (31.3–33.4) | 18.3 (17.5–19.2) | 41.3 (40.2–42.4) | 71.3 (70.3–72.3) | 32.3 (31.2–33.3) | 15.3 (14.5–16.1) | 44.2 (43.1–45.3) | 75.1 (74.1–76.0) |

| Mongolia | 30.7 (28.5–33.0) | 52.4 (49.9–54.8) | 52.0 (49.6–54.4) | 78.3 (76.2–80.2) | 34.2 (32.1–36.5) | 51.1 (48.8–53.4) | 53.1 (50.8–55.4) | 77.0 (75.0–78.9) |

| Niue | 20.9 (10.0–36.0) | 27.9 (15.3–43.7) | 27.9 (15.3–43.7) | 62.8 (46.7–77.0) | 26.7 (12.3–45.9) | 40.0 (22.7–59.4) | 40.0 (22.7–59.4) | 73.3 (54.1–87.7) |

| Philippines | 29.4 (27.6–31.2) | 28.5 (26.7–30.3) | 28.7 (27.0–30.5) | 75.1 (73.4–76.8) | 28.9 (27.4–30.5) | 24.0 (22.5–25.4) | 32.0 (30.4–33.6) | 75.6 (74.1–77.1) |

| Samoa | 29.9 (25.6–34.5) | 35.7 (31.2–40.5) | 25.0 (21.0–29.4) | 55.8 (51.0–60.6) | 37.1 (33.8–40.4) | 50.7 (47.2–54.1) | 38.1 (34.8–41.5) | 49.2 (45.8–52.7) |

| Solomon Islands | 20.9 (17.1–25.3) | 37.7 (32.9–42.6) | 29.9 (25.5–34.7) | 38.4 (33.6–43.4) | 27.1 (22.8–31.8) | 42.5 (37.6–47.5) | 33.4 (28.8–38.3) | 42.2 (37.3–47.2) |

| Tokelau | 27.5 (14.6–43.9) | 45.0 (29.3–61.5) | 25.0 (12.7–41.2) | 62.5 (45.8–77.3) | 14.3 (4.8–30.3) | 28.6 (14.6–46.3) | 20.0 (8.4–36.9) | 71.4 (53.7–85.4) |

| Tuvalu | 15.5 (11.5–20.3) | 30.3 (25.0–36.1) | 18.4 (14.0–23.5) | 83.4 (78.5–87.6) | 18.1 (14.0–22.7) | 36.1 (30.9–41.7) | 22.7 (18.3–27.7) | 92.2 (88.7–94.9) |

| Vanuatu | 19.6 (15.4–24.3) | 27.7 (23.0–32.9) | 23.5 (19.0–28.4) | 62.3 (56.9–67.6) | 21.0 (17.4–25.0) | 35.8 (31.5–40.4) | 24.7 (20.8–28.9) | 62.0 (57.4–66.4) |

| Wallis Futuna | 39.4 (33.6–45.4) | 55.6 (49.5–61.5) | 45.5 (39.5–51.6) | 76.5 (71.1–81.4) | 38.2 (32.9–43.7) | 47.4 (41.9–53.0) | 50.5 (44.9–56.0) | 76.1 (71.1–80.7) |

| Pooled estimates | 27.8 (24.1–31.6) | 34.3 (27.4–41.1) | 34.9 (29.4–40.4) | 68.2 (62.7–73.8) | 28.7 (24.4–33.0) | 35.3 (27.7–42.9) | 38.7 (33.8–43.7) | 69.5 (64.1–75.0) |

| Overall pooled estimates | 35.8 (32.7–38.9) | 41.8 (38.3–45.4) | 40.0 (37.2–42.9) | 69.6 (66.7–72.5) | 36.8 (33.5–40.2) | 41.1 (37.2–44.9) | 44.9 (42.0–47.8) | 69.7 (66.6–72.8) |

3.2. Prevalence of suicidal behaviours

Overall, girls were more likely to have any suicidal behaviour than boys (26.2% vs. 23.0%) (table 3). The pooled prevalence for suicidal ideation for boys and girls was 12.6% and 16.7%, respectively. Similar sex-specific trends were also observed for suicide planning (pooled prevalence for boys vs. girls: 13.3% vs. 16.2%) and for suicide attempt (12.2% vs. 14.4%). For both boys and girls, South-East Asia Region had the lowest prevalence for suicidal ideation, suicide planning, suicide attempt, and any suicidal behaviour. Both adolescent boys and girls from the African Region had the highest prevalence of any suicidal behaviour (Table 3), although boys from the Western Pacific region had slightly higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide planning. Boys from high-income countries had the highest prevalence of suicidal behaviours, whereas girls from the low-income countries had the lowest prevalence of suicidal behaviours (appendix p4). At country level, Laos had the lowest prevalence of suicidal ideation for both boys and girls (3.3% and 3.1%) and suicide planning (4.3% and 4.8%), while Indonesia had the lowest prevalence of suicide attempt (3.1% and 3.2%) (Table 3). Samoa had the highest prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicide planning for boys (34.8% and 45.1%, respectively), and the highest prevalence of suicide attempt for both boys and girls (58.9% and 47.9%, respectively). For girls, Kiribati had the highest prevalence of suicidal ideation (35.0%) and suicide planning (34.3%).

Table 3.

Country and region-specific prevalence of suicidal behaviours, by sex.

| Prevalence (%) with 95% CIs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | Girls | |||||||

| Suicidal ideation | Suicide planning | Suicide attempt | Any suicidal behaviour | Suicidal ideation | Suicide planning | Suicide attempt | Any suicidal behaviour | |

| African Region | ||||||||

| Benin | 8.4 (5.6–12.1) | 10.1 (6.9–14.0) | 13.3 (9.7–17.6) | 20.8 (16.4–25.7) | 16.2 (12.6–20.3) | 15.1 (11.7–19.1) | 9.4 (6.7–12.8) | 24.0 (19.8–28.6) |

| Eswatini | 15.5 (12.3–19.3) | 18.1 (14.6–22.1) | 13.9 (10.8–17.6) | 26.9 (22.8–31.4) | 15.5 (12.9–18.3) | 18.8 (16.0–21.8) | 14.1 (11.6–16.8) | 29.1 (25.9–32.6) |

| Ghana | 16.3 (13.1–19.8) | 18.5 (15.2–22.2) | 23.8 (20.1–27.8) | 34.3 (30.2–38.7) | 19.0 (15.6–22.8) | 22.4 (18.7–26.3) | 25.3 (21.4–29.4) | 38.5 (34.1–43.0) |

| Mauritania | 17.3 (14.1–20.8) | 15.3 (12.3–18.7) | 17.3 (14.1–20.8) | 25.7 (21.9–29.7) | 17.2 (14.3–20.4) | 15.6 (12.8–18.7) | 14.9 (12.2–18.0) | 27.9 (24.3–31.6) |

| Mozambique | 12.3 (8.6–16.8) | 14.9 (10.8–19.7) | 16.0 (11.8–20.9) | 27.5 (22.3–33.3) | 16.2 (12.1–21.1) | 15.1 (11.1–19.9) | 14.7 (10.8–19.5) | 31.3 (25.9–37.1) |

| Namibia | 18.5 (15.7–21.5) | 27.2 (23.9–30.6) | 27.7 (24.5–31.2) | 41.7 (38.1–45.5) | 19.2 (16.8–21.7) | 23.7 (21.1–26.4) | 21.9 (19.4–24.6) | 36.4 (33.4–39.4) |

| Seychelles | 15.1 (12.6–17.8) | 16.3 (13.7–19.1) | 16.3 (13.7–19.1) | 28.0 (24.8–31.3) | 25.2 (22.5–28.0) | 24.5 (21.9–27.4) | 18.8 (16.4–21.4) | 36.7 (33.7–39.8) |

| Tanzania | 13.5 (11.5–15.7) | 9.0 (7.4–10.9) | 8.4 (6.8–10.2) | 21.1 (18.7–23.7) | 11.1 (9.4–12.9) | 7.8 (6.4–9.4) | 9.2 (7.7–10.9) | 19.6 (17.5–21.8) |

| Pooled estimates | 14.6 (12.5–16.7) | 16.1 (11.9–20.4) | 17.0 (12.2–21.8) | 28.3 (23.2–33.3) | 17.4 (14.0–20.9) | 17.9 (12.6–23.1) | 16.0 (12.0–20.0) | 30.4 (24.9–35.9) |

| Regions of the Americas | ||||||||

| Antigua and Barbuda | 12.8 (10.0–16.2) | 13.0 (10.2–16.4) | 9.1 (6.7–12.0) | 21.7 (18.1–25.7) | 22.3 (19.0–25.9) | 22.1 (18.8–25.7) | 15.7 (12.8–18.9) | 30.1 (26.4–34.1) |

| Argentina | 10.3 (9.6–10.9) | 10.8 (10.2–11.5) | 11.7 (11.1–12.4) | 20.4 (19.5–21.2) | 21.4 (20.6–22.2) | 18.8 (18.1–19.6) | 18.0 (17.3–18.8) | 29.0 (28.1–29.8) |

| Bahamas | 15.2 (12.2–18.6) | 12.2 (9.5–15.4) | 9.7 (7.2–12.6) | 22.7 (19.1–26.6) | 21.8 (18.7–25.2) | 18.1 (15.2–21.3) | 14.0 (11.4–17.0) | 28.4 (24.9–32.1) |

| Belize | 9.3 (7.2–11.8) | 14.9 (12.3–17.8) | 8.4 (6.4–10.8) | 20.6 (17.6–23.9) | 17.3 (14.7–20.1) | 16.8 (14.2–19.6) | 13.5 (11.1–16.1) | 24.0 (21.0–27.1) |

| Bolivia | 11.9 (10.2–13.8) | 10.8 (9.1–12.6) | 14.2 (12.4–16.3) | 21.4 (19.2–23.8) | 22.7 (20.4–25.1) | 21.0 (18.8–23.3) | 23.8 (21.5–26.2) | 32.1 (29.6–34.8) |

| British Virgin Islands | 10.9 (8.2–14.0) | 12.8 (9.9–16.1) | 8.3 (6.0–11.2) | 21.3 (17.7–25.3) | 17.2 (14.2–20.4) | 16.2 (13.3–19.3) | 12.9 (10.3–15.8) | 25.7 (22.3–29.4) |

| Costa Rica | 6.8 (5.3–8.5) | 4.6 (3.4–6.0) | 5.1 (3.8–6.6) | 10.4 (8.6–12.4) | 12.7 (10.8–14.7) | 8.4 (6.9–10.2) | 9.8 (8.1–11.6) | 17.6 (15.4–19.9) |

| Curacao | 6.1 (4.3–8.3) | 6.1 (4.3–8.3) | 9.3 (7.1–12.0) | 13.5 (10.8–16.6) | 14.4 (11.9–17.2) | 10.5 (8.3–13.0) | 13.5 (11.1–16.3) | 21.1 (18.1–24.3) |

| El Salvador | 9.2 (7.3–11.5) | 7.9 (6.1–10.0) | 6.9 (5.2–8.9) | 12.8 (10.5–15.3) | 17.0 (14.3–20.0) | 13.4 (11.0–16.2) | 14.7 (12.2–17.6) | 21.9 (18.8–25.1) |

| Honduras | 13.8 (11.3–16.7) | 11.5 (9.2–14.2) | 11.1 (8.8–13.7) | 21.7 (18.6–25.1) | 23.8 (20.7–27.1) | 23.8 (20.7–27.1) | 22.0 (19.0–25.2) | 32.1 (28.7–35.6) |

| Jamaica | 17.6 (14.3–21.2) | 16.3 (13.2–19.9) | 14.9 (11.9–18.4) | 28.6 (24.6–32.8) | 25.0 (21.4–28.8) | 24.5 (20.9–28.3) | 21.4 (18.0–25.0) | 37.7 (33.6–41.9) |

| Peru | 11.4 (9.6–13.5) | 8.7 (7.1–10.6) | 11.6 (9.8–13.7) | 17.4 (15.2–19.8) | 27.6 (25.0–30.2) | 21.4 (19.1–23.9) | 22.1 (19.8–24.6) | 33.1 (30.4–35.9) |

| Saint Kitts Nevis | 12.8 (10.1–15.9) | 14.1 (11.3–17.2) | 10.9 (8.5–13.9) | 22.3 (18.8–26.0) | 18.9 (16.2–21.9) | 16.2 (13.7–19.1) | 10.3 (8.2–12.7) | 24.6 (21.5–27.8) |

| Suriname | 10.2 (7.5–13.4) | 5.4 (3.5–8.0) | 3.6 (2.1–5.8) | 13.2 (10.1–16.7) | 14.7 (11.8–18.1) | 13.0 (10.2–16.2) | 10.1 (7.6–13.0) | 18.8 (15.5–22.4) |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 12.8 (10.9–14.9) | 13.1 (11.2–15.2) | 9.8 (8.1–11.7) | 20.7 (18.4–23.1) | 18.4 (16.0–20.9) | 19.5 (17.1–22.1) | 14.0 (11.9–16.3) | 29.3 (26.5–32.2) |

| Pooled estimates | 11.2 (9.9–12.5) | 10.7 (9.0–12.3) | 9.6 (7.9–11.2) | 19.1 (16.8–21.4) | 19.6 (17.6–21.7) | 17.5 (15.1–19.9) | 15.7 (13.4–17.9) | 27.0 (24.3–29.6) |

| Eastern Mediterranean Region | ||||||||

| Afghanistan | 18.4 (14.9–22.5) | 13.9 (10.8–17.6) | 10.6 (7.9–14.0) | 26.2 (22.1–30.7) | 15.4 (12.8–18.2) | 13.1 (10.6–15.8) | 11.3 (9.1–13.9) | 26.0 (22.7–29.4) |

| Iraq | 15.5 (13.0–18.3) | 12.4 (10.1–15.0) | 11.3 (9.1–13.8) | 21.5 (18.6–24.6) | 13.4 (10.8–16.3) | 16.1 (13.3–19.3) | 14.0 (11.4–17.0) | 22.5 (19.2–26.0) |

| Kuwait | 11.4 (9.3–13.9) | 13.9 (11.6–16.6) | 8.9 (7.0–11.2) | 20.9 (18.1–24.0) | 18.8 (16.4–21.5) | 15.8 (13.5–18.3) | 13.5 (11.4–15.9) | 27.1 (24.3–30.1) |

| Lebanon | 11.4 (9.3–13.8) | 8.9 (7.1–11.1) | 10.9 (8.9–13.2) | 18.3 (15.7–21.1) | 16.4 (14.1–18.9) | 11.8 (9.9–14.1) | 13.0 (10.9–15.3) | 22.7 (20.1–25.5) |

| Morocco | 10.6 (8.9–12.6) | 11.5 (9.7–13.6) | 9.8 (8.1–11.7) | 20.3 (18.0–22.8) | 18.3 (16.0–20.7) | 15.1 (13.1–17.4) | 13.8 (11.8–16.0) | 25.9 (23.4–28.7) |

| UAE | 12.9 (10.6–15.4) | 13.7 (11.3–16.2) | 10.4 (8.3–12.7) | 22.8 (19.9–25.8) | 15.4 (13.5–17.5) | 15.2 (13.2–17.2) | 12.0 (10.2–13.9) | 24.3 (22.0–26.8) |

| Yemen | 15.2 (12.6–18.1) | 12.9 (10.4–15.6) | 12.1 (9.8–14.8) | 25.3 (22.0–28.7) | 13.1 (10.6–16.0) | 15.3 (12.6–18.3) | 11.4 (9.1–14.1) | 24.6 (21.3–28.1) |

| Pooled estimates | 13.4 (11.5–15.2) | 12.3 (10.9–13.7) | 10.4 (9.6–11.3) | 21.9 (20.0–23.8) | 15.9 (14.3–17.4) | 14.5 (13.3–15.8) | 12.7 (11.8–13.5) | 24.7 (23.5–26.0) |

| South-East Asia Region | ||||||||

| Bangladesh | 3.9 (2.8–5.4) | 6.8 (5.3–8.6) | 5.8 (4.4–7.5) | 11.6 (9.6–13.8) | 5.6 (4.6–6.9) | 6.8 (5.6–8.2) | 5.5 (4.4–6.8) | 11.7 (10.1–13.3) |

| Indonesia | 3.5 (3.0–4.2) | 5.1 (4.4–5.8) | 3.1 (2.5–3.7) | 8.1 (7.2–9.0) | 5.5 (4.8–6.2) | 5.6 (4.9–6.3) | 3.2 (2.7–3.7) | 8.9 (8.1–9.8) |

| Maldives | 9.4 (7.2–12.1) | 15.8 (12.9–19.0) | 11.3 (8.8–14.2) | 22.3 (18.9–25.9) | 14.6 (12.4–17.0) | 20.1 (17.5–22.8) | 9.8 (7.9–11.9) | 27.3 (24.4–30.3) |

| Nepal | 12.5 (11.0–14.1) | 13.0 (11.5–14.6) | 8.8 (7.6–10.2) | 21.2 (19.4–23.1) | 12.4 (11.1–13.8) | 12.6 (11.3–14.0) | 8.6 (7.5–9.8) | 21.7 (20.0–23.4) |

| Thailand | 9.8 (8.4–11.4) | 12.6 (11.0–14.3) | 9.0 (7.7–10.5) | 17.3 (15.5–19.2) | 11.5 (10.1–13.0) | 12.7 (11.2–14.2) | 10.8 (9.4–12.2) | 18.5 (16.8–20.3) |

| Timor-Leste | 9.0 (6.8–11.6) | 11.0 (8.6–13.8) | 7.9 (5.9–10.4) | 16.9 (13.9–20.2) | 7.3 (5.6–9.3) | 7.2 (5.5–9.1) | 6.6 (5.0–8.5) | 13.7 (11.5–16.2) |

| Pooled estimates | 8.0 (4.7–11.3) | 10.6 (7.0–14.3) | 7.6 (4.7–10.4) | 16.1 (10.8–21.5) | 9.4 (6.5–12.3) | 10.7 (7.2–14.3) | 7.4 (4.6–10.1) | 16.9 (11.6–22.3) |

| Western Pacific Region | ||||||||

| Brunei | 6.7 (5.1–8.7) | 4.7 (3.4–6.4) | 3.9 (2.6–5.4) | 9.7 (7.8–12.0) | 9.1 (7.3–11.1) | 7.8 (6.1–9.7) | 5.6 (4.2–7.3) | 13.5 (11.4–15.9) |

| Cook Islands | 16.5 (11.2–22.9) | 15.3 (10.2–21.6) | 11.2 (6.9–16.9) | 26.5 (20.0–33.8) | 12.8 (8.3–18.6) | 15.0 (10.1–21.1) | 12.2 (7.8–17.9) | 20.6 (14.9–27.2) |

| Fiji | 8.9 (6.7–11.4) | 9.7 (7.4–12.3) | 7.7 (5.7–10.1) | 15.9 (13.1–19.0) | 11.0 (8.7–13.5) | 12.3 (9.9–14.9) | 7.2 (5.4–9.4) | 17.7 (15.0–20.8) |

| French Polynesia | 8.4 (6.6–10.5) | 12.5 (10.3–14.9) | 5.3 (3.9–7.1) | 16.0 (13.6–18.7) | 19.8 (17.3–22.6) | 20.3 (17.7–23.1) | 13.8 (11.6–16.2) | 27.2 (24.4–30.3) |

| Kiribati | 32.4 (28.4–36.7) | 31.8 (27.8–36.1) | 27.9 (24.1–32.0) | 45.1 (40.7–49.5) | 35.0 (31.5–38.5) | 34.3 (30.9–37.8) | 31.2 (27.9–34.6) | 46.8 (43.2–50.5) |

| Laos | 3.3 (2.1–4.9) | 4.3 (2.9–6.1) | 4.6 (3.1–6.4) | 8.9 (6.8–11.3) | 3.1 (2.1–4.4) | 4.8 (3.5–6.4) | 6.6 (5.1–8.4) | 10.4 (8.5–12.5) |

| Malaysia | 6.3 (5.8–6.8) | 5.6 (5.1–6.1) | 5.4 (4.9–6.0) | 11.1 (10.4–11.8) | 8.7 (8.0–9.3) | 6.7 (6.2–7.3) | 6.8 (6.3–7.4) | 13.1 (12.4–13.9) |

| Mongolia | 16.8 (15.0–18.6) | 12.1 (10.6–13.8) | 6.9 (5.7–8.2) | 20.9 (18.9–22.9) | 26.1 (24.1–28.2) | 16.1 (14.4–17.8) | 10.8 (9.4–12.3) | 29.4 (27.3–31.5) |

| Niue | 9.3 (2.6–22.1) | 20.9 (10.0–36.0) | 16.3 (6.8–30.7) | 27.9 (15.3–43.7) | 13.3 (3.8–30.7) | 6.7 (0.8–22.1) | 6.7 (0.8–22.1) | 16.7 (5.6–34.7) |

| Philippines | 8.7 (7.6–9.8) | 9.0 (7.9–10.2) | 11.5 (10.3–12.9) | 17.9 (16.4–19.5) | 13.1 (12.0–14.3) | 11.9 (10.9–13.1) | 16.0 (14.8–17.3) | 22.2 (20.8–23.7) |

| Samoa | 34.8 (30.3–39.5) | 45.1 (40.3–49.9) | 58.9 (54.1–63.6) | 70.8 (66.2–75.1) | 27.1 (24.1–30.2) | 31.6 (28.5–34.9) | 47.9 (44.5–51.4) | 59.6 (56.1–62.9) |

| Solomon Islands | 25.4 (21.2–30.0) | 25.2 (21.0–29.7) | 27.7 (23.4–32.3) | 43.9 (39.0–48.9) | 22.9 (18.8–27.3) | 22.9 (18.8–27.3) | 32.9 (28.3–37.8) | 44.7 (39.8–49.8) |

| Tokelau | 27.5 (14.6–43.9) | 30.0 (16.6–46.5) | 27.5 (14.6–43.9) | 42.5 (27.0–59.1) | 22.9 (10.4–40.1) | 34.3 (19.1–52.2) | 25.7 (12.5–43.3) | 42.9 (26.3–60.6) |

| Tuvalu | 10.8 (7.4–15.1) | 10.8 (7.4–15.1) | 10.5 (7.1–14.7) | 22.7 (17.9–28.1) | 4.0 (2.2–6.8) | 8.1 (5.4–11.6) | 4.4 (2.4–7.2) | 12.8 (9.3–16.9) |

| Vanuatu | 18.1 (14.1–22.6) | 20.2 (16.0–24.9) | 25.9 (21.3–31.0) | 41.3 (35.9–46.8) | 17.0 (13.7–20.7) | 18.5 (15.0–22.3) | 18.0 (14.6–21.8) | 33.0 (28.8–37.5) |

| Wallis Futuna | 14.1 (10.2–18.7) | 24.5 (19.6–30.1) | 10.8 (7.4–15.1) | 28.2 (22.9–33.9) | 27.8 (23.0–33.0) | 31.8 (26.8–37.2) | 15.9 (12.1–20.3) | 37.0 (31.8–42.5) |

| Pooled estimates | 14.8 (11.8–17.8) | 16.7 (13.3–20.0) | 15.6 (12.1–19.1) | 27.6 (21.7–33.5) | 16.9 (13.0–20.8) | 17.1 (13.4–20.8) | 16.1 (12.1–20.0) | 27.8 (21.7–33.9) |

| Overall pooled estimates | 12.6 (11.3–13.9) | 13.3 (12.0–14.6) | 12.2 (10.8–13.6) | 23.0 (20.7–25.2) | 16.7 (14.8–18.7) | 16.2 (14.4–18.0) | 14.4 (12.6–16.2) | 26.2 (23.6–28.9) |

3.3. Associations between parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours

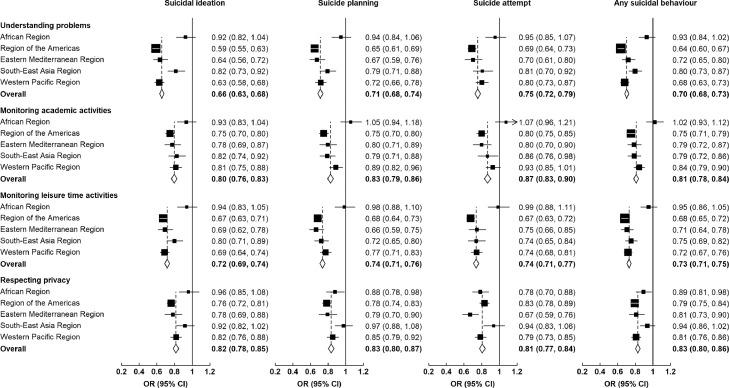

Overall, all four variables defining parents-adolescent relationship were strongly associated with lower odds of suicidal ideation, suicide planning, suicide attempt, and as expected, with overall suicidal behaviour (Fig. 2). Adolescents who reported their parents understood their problems had the lowest ORs for overall suicidal behaviour (0.70, 95% CI: 0.68–0.73) as well as suicidal ideation (0.66, 0.63–0.68), suicide planning (0.71, 0.68–0.74), and suicide attempt (0.75, 0.72–0.79). Among the other three parents-adolescent relationship variables, monitoring of leisure time activities was associated with greater decrease in odds for any of the suicidal behaviours (OR for overall suicidal behaviour: 0.73, 0.71–0.75). There were strong and persistent associations for parental understanding of problems, monitoring academic and leisure time activities with suicidal behaviour among all WHO regions expect for African region. Respective privacy was not significantly associated with suicidal behaviour in South-East Asia region (Fig. 2). The associations between parents-adolescent relationship and suicidal behaviour were the strongest in the Regions of the Americas. In a separate analysis with adjustments for each other, all four parents-adolescent relationship variables remained strongly associated with any suicidal behaviour (Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Associations between of various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours in adolescents, overall and by region.

Multi-level mixed-effect logistic regressions were adjusted for age, sex, grade, proxy for low socioeconomic status, survey year, country income classification, loneliness, sleeping problem, peer support, bullying, truancy, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and overweight.

Table 4.

Associations of various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and any suicidal behaviour.

| OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|

| Understanding problems | |

| Adjusted for all other variables* | 0.70 (0.68–0.73) |

| Additionally adjusted for: | |

| Monitoring academic activities | 0.73 (0.70–0.75) |

| Monitoring leisure time activities | 0.76 (0.73–0.79) |

| Respecting privacy | 0.69 (0.67–0.72) |

| Adjusted for all of the above | 0.77 (0.74–0.80) |

| Monitoring academic activities | |

| Adjusted for all other variables* | 0.81 (0.78–0.84) |

| Additionally adjusted for: | |

| Understanding problems | 0.89 (0.86–0.92) |

| Monitoring leisure time activities | 0.87 (0.84–0.90) |

| Respecting privacy | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

| Adjusted for all of the above | 0.90 (0.87–0.93) |

| Monitoring leisure time activities | |

| Adjusted for all other variables* | 0.73 (0.71–0.75) |

| Additionally adjusted for: | |

| Understanding problems | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

| Monitoring academic activities | 0.75 (0.73–0.78) |

| Respecting privacy | 0.72 (0.69–0.74) |

| Adjusted for all of the above | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

| Respecting privacy | |

| Adjusted for all other variables* | 0.83 (0.8–0.86) |

| Additionally adjusted for: | |

| Understanding problems | 0.81 (0.79–0.84) |

| Monitoring academic activities | 0.81 (0.79–0.84) |

| Monitoring leisure time activities | 0.81 (0.78–0.83) |

| Adjusted for all of the above | 0.79 (0.77–0.82) |

Multi-level mixed-effect logistic regressions were adjusted for age, sex, grade, proxy for low socioeconomic status, survey year, country income classification, loneliness, sleeping problem, peer support, bullying, truancy, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and overweight.

We explored the individual effects of adjustment for various demographic, psychosocial, and lifestyle factors on the associations of parents-adolescent relationship variables and suicidal behaviour variables (Appendixp5-p8). Each of these factors had little effect individually on these associations and the fully adjusted ORs did not vary too much from the corresponding unadjusted ORs. We also observed significant trends (Ptrend<0.001) for the observed associations when using the original 5-point scale for parents-adolescent relationship variables used in the questionnaire (Appendixp9).

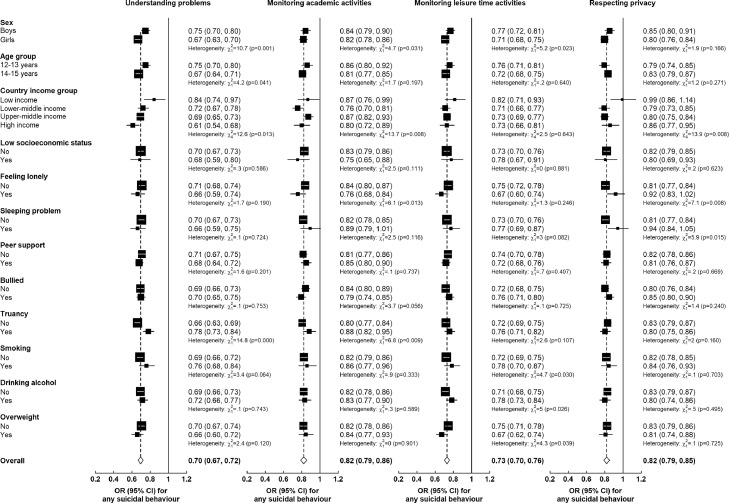

We then compared the associations of four parents-adolescent relationship variables with overall suicidal behaviour across subgroups of various individual factors, including sex, age group, country income group, low socioeconomic status, loneliness, sleeping problem, peer support, smoking, alcohol drinking, and overweight (Fig. 3). Compared to adolescent boys, girls had lower odds of overall suicidal behaviour associated with understanding problem, monitoring academic activities, and monitoring leisure time activities. There was evidence that the effects of respecting privacy on suicidal behaviour were less pronounced among those who were lonely and had sleeping problem. There was evidence of heterogeneity for the association between monitoring leisure time activities and suicidal behaviour among those who were smokers and drank alcohol (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Associations between various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and any suicidal behaviour, by levels of other factors.

Multi-level mixed-effect logistic regressions were adjusted for age, sex, grade, proxy for low socioeconomic status, survey year, country income classification, loneliness, sleeping problem, peer support, bullying, truancy, cigarette smoking, alcohol drinking, and overweight, as appropriate. Heterogeneity between groups was tested by likelihood ratio tests comparing models with and without cross product interaction term.

Discussion

In this multi-country study based on nationally-representative samples of adolescents aged 12–15 years, we found that nearly one-third of the adolescents reported that their parents understood problems and monitored their academic and leisure time activities, while about two-thirds reported that their parents respected their privacy. Compared to boys, higher proportion of girls reported about either suicidal ideation, suicide planning, or suicide attempt in previous 12 months. There were substantial variations in the estimates for parents-adolescent relationship and suicidal behaviours by WHO regions and country-income classification groups. Variables representing different aspects of parents-adolescent relationships (e.g. understanding problems, monitoring academic activities, monitoring leisure time activities, and respecting privacy) were strongly (and independently of each other) associated with lower odds of suicidal behaviours. The associations between parents-adolescent relationship and suicidal behaviours were slightly stronger in girls than those in boys. There was also evidence of heterogeneity in some of the associations by factors like feeling lonely, sleeping problems, smoking, and drinking alcohol.

We provided a comprehensive assessment of parents-adolescent relationship by looking at different aspects of such relationship, for example, emotional support, monitoring activities, and respecting privacy. Our results confirm that there are substantial variations across countries and regions in the levels of parents-adolescent relationships. These variations may in part reflect differences in parenting styles and approaches across diverse economic, cultural, and religious settings [23], [24], [25]. We also found that parents of adolescent girls monitored their leisure activities more than parents of adolescent boys, whereas the differences for other aspects of the relationship did not vary widely between sexes. However, our results are not directly comparable to other studies looking at parental factors, particularly because each study measured various aspects of parental support and relationship using different definitions [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16],18,23,26].

Our findings of higher prevalence of suicidal behaviours among girls than boys across all regions are consistent with findings from previous research [[4], [5], [6],16,17,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31]]. Sex differences in suicidal behaviour might be related to girls’ higher vulnerability to psychosocial distress, internalising problems, domestic violence, and sexual abuse [32]. We observed significant cross-country differences in the prevalence of suicidal behaviours, which was also seen in previous studies. For example, prevalence of suicidal ideation among adolescents aged 15–16 years in 17 European countries ranged from 15% to 31.5%, while the prevalence of suicidal attempts ranged from 4.1% to 23.5% [33]. On the other hand, the prevalence estimates for suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempt in US, based on the nationally representative sample of the Youth Risk Behaviour Survey (YRBS), were 17.2%, 13.6%, and 7.4% [34]. The prevalence estimates for suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempt in our study are similar to previous multi-country studies based on GSHS surveys [4], [5], [6]. However, slight differences in these prevalence estimates are expected due to differences in datasets and analysis samples. For example, Uddin and colleagues [6] reported that the prevalence estimates based on analyses of adolescents aged 12–17 years from 59 low-income and middle-income countries, whereas we included adolescents aged 12–15 years from 52 countries without any restriction on country income group classification. They also included surveys conducted between 2003 and 2015 whereas we excluded surveys conducted before 2009 because those surveys did not have information on all the variables of our interest. By restricting our analyses to surveys conducted after 2009 and to adolescents aged 12–15 years, we are confident that our cross-country comparisons are less likely to be biased.

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis on the associations between different aspects of parents-adolescent relationship and different forms of suicidal behaviours, and found that parental factors like understanding problems, monitoring academic activities, monitoring leisure time activities, and respecting privacy were strongly (and independently of each other) associated with lower odds of suicidal behaviours in adolescents. Previous studies examined the roles of some parental factors on adolescent suicidal behaviours. A recent study based on the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study in US found that low parental monitoring was significantly associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among children aged 9–10 years [11]. Another study based on the French i-Share cohort found that those with lack of perceived parental support in childhood and adolescence were more likely to have occasional and frequent suicidal thoughts, compared to those who had strong parental support [14]. Other factors indicating poor relationship with parents including lack of parental nurturance, parental rejection, family discord, and negative relationship with parents were associated with suicidal ideation and attempts [12,18]. Positive parents-adolescent relationships can confer resilience to suicidal behaviours by attenuating the impacts of bullying, peer victimization, sexual abuse, feelings of hopelessness, and depressive symptoms [1].

The associations between parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours varied across WHO regions and the World Bank country income classification. For example, in the African region, the associations between parents-adolescent relationship variables and different forms of suicidal behaviour were either non-significant or less pronounced than other WHO regions, despite the fact that prevalence of suicidal behaviour was the highest in this region. African countries have higher rates of poverty and illiteracy, and it is plausible that various aspects of parents-adolescent relationship can be affected by parents’ time constraints and/or literacy level. Adolescents in these countries also experience higher levels of adverse life events (e.g. political tensions, violence, violation of human rights, displacement and migration, and HIV/AIDS) affecting their mental wellbeing and precipitating suicidal behaviours [6]. These factors can modify the associations between parents-adolescent relationship and suicidal behaviour in African region. We also found that the levels of respecting privacy and suicidal behaviours were the lowest in South-East Asia region and there was no association between respecting privacy and suicidal behaviour. These findings might reflect the underlying sociocultural conservatism and religious beliefs in this region. When we looked at the associations separately by country income groups, it was evident that parents’ relationship with their adolescents had less influence on suicidal behaviour among adolescents in the low-income countries. This highlights that the impacts of parents-adolescent relationship might be different in societies where many people struggle for basic subsistence than affluent societies. More research is needed to explore the potential roles of sociocultural, political, religious, and economic factors on these associations.

The findings of our study may have important clinical and public health implications. Many factors influencing suicidal behaviour in adolescents are not directly modifiable but improving parental relationships present targets for suicide prevention intervention by interrupting the ideation-to-action transition. However, further research on family intervention programs is needed to inform policy and related actions.

Our study has several strengths. First, we included a large number of adolescents from 52 countries across different WHO regions, most of which are nationally representative samples. Second, the estimates reported in this study were obtained by use of weighted analyses to account for the probability of selection and distribution of the population by sex and age. The weighted analyses facilitate generalisation of findings to the entire country population. Third, the GSHS used the same standardised methods for participant selection, questionnaire development and data collection, which are more likely to produce results that are comparable across countries and regions. Fourth, for investigating the association between parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours, we adjusted for a wide range of covariates as well as explored any further potential for effect modification by various factors.

The limitations of our study include the use of self-reported data to define various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours. The validity of self-reported data might be affected by adolescents’ ability to understand the questions, differences in sociocultural backgrounds, and recall problems. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility of biases in our prevalence estimates arising due to missing data, possible data entry errors, and high levels of heterogeneity between country-specific estimates. In some countries and cultures, talking about suicidal behaviours is tabooed and therefore, the prevalence of such measures might be under-reported [4,6]. Given the rising burden of mental health issues among adolescents in recent years, careful considerations are needed while interpreting the prevalence of suicidal behaviour from our study which is based on GSHS datasets between 2009 and 2015. Although we used four variables to understand various aspects of parents-adolescent relationship, we acknowledge that conceptualisation of a complex phenomenon like parents-adolescent relationship is still incomplete and will require more detailed evaluation in the future. Due to cross-sectional design of the study the associations between parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours should be interpreted with cautions for issues like reverse causation and residual confounding. Importantly, we could not adjust for factors like depression, previous suicidal attempt, family conflict, and abusive relationship. Only a few countries had available information on substance use and when we adjusted substance use in the model in an analysis restricted to those countries, the observed associations remained unchanged (data not shown).

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated that there are important differences in the prevalence estimates for various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours by sex, WHO regions, and country-income classifications. We have also shown that adolescents who reported that their parents understood their problems, monitored their academic and leisure time activities, and respected their privacy were less likely to have suicidal behaviours. The associations between various aspects of parents-adolescent relationships and suicidal behaviours were independent of each other. Despite these associations varied by WHO regions and sex, they were consistently strong across various sociodemographic, psychosocial, and lifestyle factors.

Data sharing

Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) datasets used in this study are publicly available in this link: https://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/datasets/en/.

Funding

No funding was available for this study.

Authors’ contributions

Md Shawon and Sayedul Kushal had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Sayedul Kushal and Md Shawon involved in study concept and design. Md Shawon involved in statistical analysis and interpretations of results. Shusama Reza conducted relevant literature search. Sayedul Kushal and Yahia Amin involved in drafting of the manuscript. Md Shawon and Shusama Reza involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors confirmed that they have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

We thank the US Centers for Disease Control and WHO for making Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) data publicly available for analysis. We thank the GSHS country coordinators and other staff members, and the participating students and their parents.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100691.

Contributor Information

Sayedul Ashraf Kushal, Email: kushal@lifespringweb.com.

Yahia Md Amin, Email: yahia@lifespringweb.com.

Shusama Reza, Email: shusama.lifespring@gmail.com.

Md Shajedur Rahman Shawon, Email: s.shawon@unsw.edu.au.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Gallagher M.L., Miller A.B. Suicidal thoughts and behavior in children and adolescents: an ecological model of resilience. Adolesc Res Rev. 2018;3(2):123–154. doi: 10.1007/s40894-017-0066-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organisation. Suicide rate estimates, age-standardized Estimates by country. 2017. https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.MHSUICIDEASDR?lang=en (accessed 01 September 2020).

- 3.Organization W.H. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. 2014.

- 4.McKinnon B., Gariepy G., Sentenac M., Elgar F.J. Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(5) doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.163295. 340-50F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang J.J., Yu Y., Wilcox H.C. Global risks of suicidal behaviours and being bullied and their association in adolescents: school-based health survey in 83 countries. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;19 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uddin R., Burton N.W., Maple M., Khan S.R., Khan A. Suicidal ideation, suicide planning, and suicide attempts among adolescents in 59 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2019;3(4):223–233. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30403-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kienhorst I.W.M., De Wilde E.J., Diekstra R.F.W. Suicidal behaviour in adolescents. Arch Suicide Res. 1995;1(3):185–209. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carballo J.J., Llorente C., Kehrmann L. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(6):759–776. doi: 10.1007/s00787-018-01270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mars B., Heron J., Klonsky E.D. Predictors of future suicide attempt among adolescents with suicidal thoughts or non-suicidal self-harm: a population-based birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(4):327–337. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30030-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strandheim A., Bjerkeset O., Gunnell D., Bjornelv S., Holmen T.L., Bentzen N. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts in adolescence–a prospective cohort study: the Young-HUNT study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVille D.C., Whalen D., Breslin F.J. Prevalence and family-related factors associated with suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and self-injury in children aged 9 to 10 years. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fotti S.A., Katz L.Y., Afifi T.O., Cox B.J. The associations between peer and parental relationships and suicidal behaviours in early adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(11):698–703. doi: 10.1177/070674370605101106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang B.H., Kang J.H., Park H.A. The mediating role of parental support in the relationship between life stress and suicidal ideation among middle school students. Korean J Fam Med. 2017;38(4):213–219. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2017.38.4.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macalli M., Tournier M., Galera C. Perceived parental support in childhood and adolescence and suicidal ideation in young adults: a cross-sectional analysis of the i-share study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):373. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1957-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oppenheimer C.W., Stone L.B., Hankin B.L. The influence of family factors on time to suicidal ideation onsets during the adolescent developmental period. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;104:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaborskis A., Sirvyte D., Zemaitiene N. Prevalence and familial predictors of suicidal behaviour among adolescents in Lithuania: a cross-sectional survey 2014. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:554. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3211-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziaei R., Viitasara E., Soares J. Suicidal ideation and its correlates among high school students in Iran: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1298-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Consoli A., Peyre H., Speranza M. Suicidal behaviors in depressed adolescents: role of perceived relationships in the family. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2013;7(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The World Bank. World bank country and lending groups: country classification. 2019. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 17 April 2020).

- 20.World Health Organisation. Global school-based student health survey (GSHS). http://www.who.int/ncds/surveillance/gshs/en/ (accessed 10 March 2020).

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Global school-based student health survey (GSHS) https://www.cdc.gov/gshs/index.htm (accessed 23 February 2020).

- 22.World Health Organisation. Growth reference data for 5-19 years. https://www.who.int/growthref/en/#:~:text=The%20WHO%20Reference%202007%20is,standards%20sample%20for%20under%2Dfives. (accessed April 24 2020).

- 23.Ahmedbookani S. Psychological well-being and parenting styles as predictors of mental health among students: implication for health promotion. Int J Pediatr. 2014;2(3.3):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barton A.L., Kirtley M.S. Gender differences in the relationships among parenting styles and college student mental health. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(1):21–26. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.555933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Uji M., Sakamoto A., Adachi K., Kitamura T. The impact of authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting styles on children's later mental health in Japan: focusing on parent and child gender. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23(2):293–302. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jantzer V., Haffner J., Parzer P., Resch F., Kaess M. Does parental monitoring moderate the relationship between bullying and adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior? A community-based self-report study of adolescents in Germany. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:583. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1940-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahfoud Z.R., Afifi R.A., Haddad P.H., Dejong J. Prevalence and determinants of suicide ideation among Lebanese adolescents: results of the GSHS Lebanon 2005. J Adolesc. 2011;34(2):379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Page R.M., Saumweber J., Hall P.C., Crookston B.T., West J.H. Multi-country, cross-national comparison of youth suicide ideation: findings from Global School-based Health Surveys. Sch Psychol Int. 2013;34(5):540–555. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pandey A.R., Bista B., Dhungana R.R., Aryal K.K., Chalise B., Dhimal M. Factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts among adolescent students in Nepal: findings from global school-based students health survey. PLoS One. 2019;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voss C., Ollmann T.M., Miche M. Prevalence, onset, and course of suicidal behavior among adolescents and young adults in Germany. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson M.L., Dunlavy A.C., Viswanathan B., Bovet P. Suicidal expression among school-attending adolescents in a middle-income sub-Saharan country. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(11):4122–4134. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9114122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruch D.A., Sheftall A.H., Schlagbaum P., Rausch J., Campo J.V., Bridge J.A. Trends in Suicide Among Youth Aged 10 to 19 Years in the United States, 1975 to 2016. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193886. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kokkevi A., Rotsika V., Arapaki A., Richardson C. Adolescents' self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):381–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Youth risk behavior survey: data summary and trends report, 2007-2017, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.