Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is spreading all over the world in a short time. It originated from Wuhan City of China in the late 2019. Proper vaccines have still been in progress; the spread of the virus is contracted by lockdown and social distancing protocols. These lockdowns resulted in significant benefits, improving the quality of air and reducing the level of environmental pollution. In this context, the study proposes to identify the air quality in the region and its relation with COVID-19-affected people in metropolitan cities of India during COVID-19 lockdowns using a geographical information system (GIS), where over 90% of commercial and industrial sites and 100% school and colleges were closed. The study outcomes highlight the areas encountering high levels of pollution under the pre-lockdown scenario and have seen a higher number of cases. The relation is most evident for PM2.5, which is responsible for respiratory disorders and is the place of attack of SARS-CoV-2. This approach provides comparable outcomes with other decision-making tools. Our primary precedence should be to develop communities to enable people to remain healthy and stay. Healthy societies are crucial not only for people’s health, but also for sustainable development. Centered on GIS is concealed; moreover, it is very flexible to use by policymakers.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, SDGs, Fine particulate matter, Ozone (O3), GIS, Thiessen polygon

Introduction

Many places worldwide are affected by the novel coronavirus's presence and transmission (World Health Organization 2020; Gautam and Hens 2020). On May 31, 2020, India recorded 4971 and 173,763 deaths and confirmed cases, respectively, due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (AajTak news 2020). The pandemic emerged in December 2019 in Wuhan City and spread to other parts of the world (Bherwani et al. 2020a; Gautam 2020a). In the present problematic situation, the affected countries' governments have established strategies to reduce COVID-19 among their people. In this regard, the Indian Government applied a series of lockdowns including self-lockdown—“Janta Curfew” (March 22, 2020), lockdown-1 (March 24, 2020, to April 14, 2020), lockdown-2 (April 15, 2020, to May 3, 2020), lockdown-3 (May 4, 2020, to May 17, 2020), and lockdown-4 (May 18, 2020, to May 31, 2020).

These lockdowns and control actions reduced the impact of COVID-19 and were correlated with the ambient air quality in local or regional areas (Gautam 2020b). The degree of air quality, which influences breathing for a particular time also characterized air pollutants' possible effects and summarized using an air quality index (AQI) (Gautam et al. 2020b; Fareed et al. 2020; Gautam and Trivedi 2020). Air quality is a major concern for not only local public health, but also for the economy (Gautam et al. 2020b; Nair et al. 2020). They have extensively studied the impact of the current problems and possible control measures to improve the environment (Humbal and Gautam 2019; Gautam et al. 2020b). We collected the secondary data from various sampling stations in India's different areas provided by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), a central body of India's Government, to assess air quality. Data were collected from two periods, before lockdown (December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020) and during lockdown (March 25, 2020, to May 30, 2020). For this study, 24-h daily averages were used to calculate the average particulate matter (PM) concentration for all the states. Some states have multiple air monitoring stations. Final data are taken as an average of all stations from December 1, 2019, to March 24, 2020, and from March 25, 2020, to May 30, 2020. These data points are imported in an ArcGIS to establish PM2.5 and O3 concentration distributed maps for the country's states. The states are ranked based on their average concentrations.

Immediate strategic decision of COVID-19-related lockdown may have improved air quality; however, there are compounding effects related to various sustainable development goals (SDGs). During the pandemic, energy demands have changed and have become an intractable problem. Without access to electricity, services of health care have stopped, which directly affects the health facilities. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) stretches statistics on poverty, unemployment, labor scarcity, etc. Migration of people is surveyed online by the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) and has set the migration of people data from urban to rural areas. The economy and e-commerce have a worse effect on the livelihood of Indian citizens (Poddar and Yadav 2020).

Materials and methods

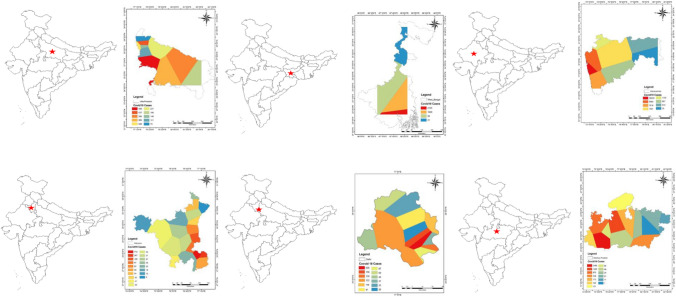

Authors studied six states (i.e., Maharashtra, Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh) of India, including air pollutants (i.e., PM2.5, PM10, and O3) and AQIs from 2019 to 2020 (especially on and before the lockdowns activities). Data were standardized. They discussed using the Thiessen polygon—an advanced geographical information system (GIS) technology (Gautam et al. 2020b). Thiessen polygons (also known as Voronoi cells) define and delineate proximal regions around individual data points by using polygonal boundaries. Thiessen map is created using all air monitoring station locations and COVID-19 case data for each station. Locations (selected station) are used as a point for data, and cases are used to spread the boundary of the region. In ArcMap, Thiessen polygons can be established using the Create Thiessen Polygons tool and then represent all station's location data as a point and categories in different color codes according to their COVID-19 cases. The possible outcome will help decision-makers to establish strategies to reduce the impact of COVID-19. The selected states show huge transportation activities, highly polluted area, and many cases so that the relationship between affected people and air quality can be evidenced. The proposed objectives of the perspectives are to assess the status of air quality index in India's metropolitan cities by using Thiessen polygons and to assess the relationship between air quality and COVID-19-affected person using the standard deviation, mean, and rank algorithm. The main advantage of using rank algorithms is that they are flexible and autonomous to understand the COVID-19-affected and air quality area status according to rank-wise. When expert opinion is not available, it will help decide pre- and postcondition. Thiessen polygons are a very appropriate technique. However, data availability is a significant limitation of the technology.

Statistical analysis for the six shortlisted states shows the correlation between our pollution and the states' number of cases. T tests are performed between the average pollution loads and patients per 10 million population (CPP) and the number of instances per sq. km. area (CPA) of the state. The normalization of COVID-19 cases allows understanding the distribution of cases vis-a-vis air quality data. The air quality data have also been averaged for the state area. Hence, the normalization should result in a better comparison as standalone concentration and cases.

Further analysis is carried out concerning impacts on SDGs due to COVID-19 lockdown. CMIE shows that people lose their jobs during the lockdown, referred to as unemployment and poverty statistics. The movement of people has been tracked using the HAL database. Various research literature works are compiled for understanding the influence on other sustainable development goals and are reported with a positive or negative impact.

Results and discussion

Increased urbanization and related activities result in rapidly growing air pollution in India. Air quality data of PM2.5 and ozone for all stations are taken from Central Control Room (CCR) for country-wide air quality management, CPCB. The concentration of pollutants is considered for the period December 1, 2019, to March 25, 2020, and from March 26, 2020, to May 30, 2020. After the outbreak of COVID-19 virus, India announced lockdown from March 25, 2020. The above two dates bifurcate the several pre- and post-COVID-19 lockdowns in India. The COVID-19 pandemic changed several patterns and at the medical, economic, political, and social systems’ unsolved resistor. The corresponding drop in regional traffic, reduced industrial and commercial activity, has led to a significant decline in air pollution emissions. Air quality with respect to PM2.5 and ozone concentration is compared between the pre-lockdown and during the lockdown period. For further analysis, few states are considered due to better data in those states and the spread of geographical and economic diversity. The states considered for further analysis are Maharashtra, Delhi, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh. Delhi, Haryana, and Maharashtra are among the top polluter states/union territories and are economically ahead of most other states in India. West Bengal is a coastal state, while Madhya Pradesh is centrally located. One of the prime reasons for shortlisting these states was the presence of a high number of COVID-19 cases. COVID-19 cases are noted in each station's area for the respective states up to May 30, 2020. Population density of population and geographical area for observed states are considered. The data for the selected states considered for analysis are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

State-wise comparison of air quality and COVID-19-affected cases regions of India

| State | PM2.5 (µg m−3) | Ozone (µg m−3) | COVID-19-confirmed cases | Population in 10 million | Area (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delhi | 141.11 | 26.01 | 18,549 | 1.9 | 1483 |

| Assam | 119.03 | 19.00 | 1217 | 3.6 | 78,438 |

| West Bengal | 96.12 | 32.74 | 5130 | 10.09 | 88,752 |

| Bihar | 83.93 | 31.53 | 3565 | 12.85 | 94,163 |

| Odisha | 81.45 | 25.94 | 1819 | 4.71 | 155,707 |

| Maharashtra | 56.51 | 41.23 | 65,168 | 12.49 | 307,713 |

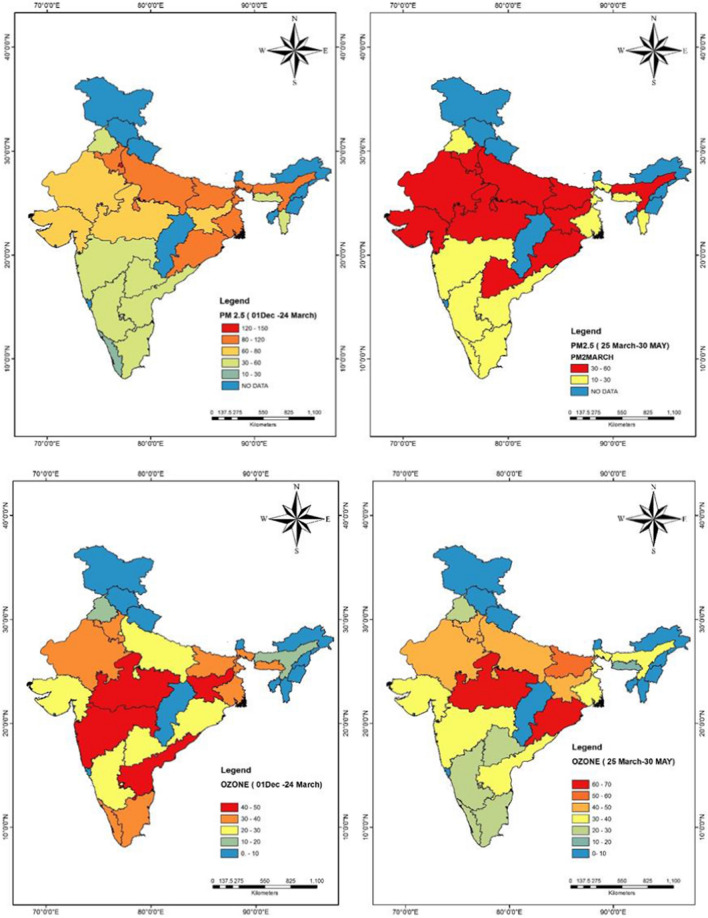

The averaged values for PM2.5 and ozone are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. Figure 1 provides evidence that PM2.5 drastically reduced in India during the lockdown period. Five of the six states were considered rush among the top of the highly polluted states with the highest PM2.5 concentrations during the pre-lockdown period. Ozone shows that its concentration increased slightly during the lockdown period in states for which data are shown in figures but are not considered for further analysis.

Fig. 1.

Air quality levels in regional scale: a particle of 2.5 mm or less (PM2.5) (December 1, 2020–March 24, 2020); b particle of 2.5 mm or less (PM2.5) (March 25, 2020–May 30, 2020); c ozone (O3) (December 1, 2020–March 24, 2020) and d ozone (O3) (March 25, 2020–May 30, 2020)

Fig. 2.

Variation in air quality index in six Indian states during three lockdown periods (from December 1, 2019, to March 25, 2020, and from March 26, 2020, to May 30, 2020)

COVID-19 cases are analyzed in the six shortlisted states. The PM2.5 and O3 concentrations are correlated with CPP and CPA using t-tests. The results of the t tests are shown in Table 2. The normal distribution of the values of PM2.5, O3, CPP, and CPA has been controlled using kurtosis and skewness (K–S) values ranging between − 2 and + 2 except for CPA. The CPA, however, follows a linear trend with PM2.5 and ozone with correlation coefficient close to 0.75 for PM2.5.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis using t tests for equality of means

| PM2.5 with CPP | PM2.5 with CPA | Ozone with CPP | Ozone with CPA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 94.026 | 94.026 | 35.202 | 35.202 |

| Variance | 945.608 | 945.608 | 76.833 | 76.833 |

| Observations | 6.000 | 6.000 | 6.000 | 6.000 |

| Hypothesized mean difference | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Df | 5.000 | 5.000 | 5.000 | 8.000 |

| t Stat | − 1.792 | 7.221 | − 1.830 | 7.994 |

| P(T ≤ t) one-tail | 0.067 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.000 |

| t Critical one-tail | 1.476 | 1.476 | 1.476 | 1.397 |

| P(T ≤ t) two-tail | 0.133 | 0.001 | 0.127 | 0.000 |

| t Critical two-tail | 2.015 | 2.015 | 2.015 | 1.860 |

Table 2 shows that there is a significant correlation between PM2.5 and O3 with CPA. The p value is less than 0.05 for one tail and two tails for both parameters, and t-stat value is higher than t-critical (one tail and two tails). Thus, the null hypothesis can be rejected. This indicates a strong dependence of COVID-19 cases within an area with the level of pollution found in that area. While CPP has been widely used to understand the level of PM2.5 and O3 penetration of the disease in the state, it does not significantly correlate with pollution levels.

Thiessen polygons are prepared for the selected states. As shown in Fig. 2, COVID-19 cases increased with higher pollution concentrations before the lockdown period. Pollution levels are higher in areas where industrial activities are intense and used compounds with a high COVID-19-confirmed cases evidence. More COVID-19 cases are found where there are high PM2.5 levels often above the permissible limits. In Delhi, pollutant levels are very high throughout the city. PM2.5 is excessive in Nehru Nagar (187.13 µg m−3), and the confirmed cases in this area are also very high. The pollution level in Aya Nagar is 103.6 µg m−3, and the number of cases recorded in this area is about 25. The union territory observed where the pollution is more, cases recorded are high and vice versa. The same applies to Maharashtra, Mumbai City, which shows the highest PM2.5 levels among the city in Maharashtra. PM2.5 values read 76.53 µg m−3 and here are 38,220 confirmed cases. PM2.5 in Nagpur and Chandrapur is about 38.71 and 34.48 µg m−3, and the COVID-19 cases confirmed are 574 and 25. The same scenario is observed in Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal.

In Haryana, Gurugram, PM2.5 is 114.78 µg m−3 and 774 confirmed cases are reported. The pollutant level ranges between 80 and 95 µg m−3, and the number of confirmed cases is in the range of 31–367, whereas in Sonipat, Haryana, the observed pollutant level is 37.30 µg m−3, and with cases, this is an outlier. A similar scenario is observed in Uttar Pradesh that, with the pollutant level above 80 µg m−3, the cases recorded were between 300 and 450, and with the pollutant level below 80 µg m−3, the observed cases are in the range of 150, whereas in Agra, the pollutant level is 82.04 µg/m3 with 882 cases confirmed similar to Sonipat. These cities are outliers and have very high population density which might be the reason for the increasing number of cases (Sharma et al. 2020; Tobías et al. 2020). However, in general, the states show a trend in which high PM2.5 concentration coincides with a high number of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

Ozone concentrations in Delhi, Haryana, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal are in the range between 6 and 48 µg m−3, 11 and 78 µg m−3, 31 and 64 µg m−3, 34 and 69 µg m−3, 7 and 58 µg m−3, and 24 and 54 µg m−3, respectively. The states of Haryana, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh follow an inverse trend with respect to O3 concentration and COVID-19 cases. All the above states are geographically diverse and massive in nature. Other states like West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, and Delhi do not show any straightforward relation. Hence, concluding on the impact of ozone is very difficult. Perhaps, robust data on a more significant number of states and longer time duration may help extract concrete conclusions (Cohen and Brauer 2017; Wang et al. 2020).

Based on the above observations, the environment has improved over time during the lockdown in air pollution. However, further review of published literature and collation of data reveals the facts about other SDGs that are not as promising as the environment. The red color in tables indicates a negative impact or deterioration or reduction in values, while the blue color suggests improvements positively. Quantification has been done based on the available literature wherever possible. It is important to note that the impact of COVID-19 would be different in different societies based on social structure, economic well-being, population density, availability of resources, etc. While an early attempt to understand the impact of COVID-19 on SDGs is made here, it is prudent that detailed analysis in quantitative terms should be made based on the above factors, which will give an in-depth understanding of the respective impacts based on diversity and resilience of the society.

SDG 01: No poverty

It has been observed that many people lost their jobs during COVID-19 lockdown. Table 3 indicates the impact on various indicators of SDG01 and further suggests the possible changes in the scenario in the near future after the lockdown is over.

Table 3.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 01

SDG 02: Zero hunger

Given the linkage between poverty and hunger, the condition has deteriorated in India during the lockdown which is evident in Table 4. However, the situation is poised to improve shortly.

Table 4.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 02

| SDG 02—zero hunger | During COVID-19 lockdown | Post-COVID-19 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food |

|

||

|

Bhat et al. (2020) |

SDG 03: Good health and well-being

While India is battling from COVID-19, the health care spending percentage share of GDP decreased pre- and during the lockdown, whereas given the severity of the pandemic, the share of spending is bound to increase in the near future. Further, health care itself improved during this time and will continue to improve in the near future. The impacts on mental and physical health are also consolidated in Table 5

Table 5.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 03

SDG 06: Clean water and sanitation

The environment has shown improvement, as indicated above, concerning air pollution. Similar improvements have been observed in water quality. However, the situation might soon worsen with increased water consumption due to sanitation and the reopening of locked-up industries. India needs to prepare for this outcome, which seems inevitable. Table 6 gives the comparison of different indicators.

Table 6.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 06

SDG 08: Decent work and economic growth

Due to continuous lockdown, this SDG is bound to get affected in a negative way. The indicators such as labor scarcity, e-commerce, and GDP growth all suffered a toll and are predicted to improve over time. The consolidated results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 08

| SDG 08—decent work and economic growth | During COVID-19 lockdown | Post-COVID-19 | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migrant labor scarcity |

|

CMIE (2020a) | |

|

|

|||

| Labor participation rate (LPR) |

|

CMIE (2020c) | |

|

|

|||

| Economy |

|

Pratheesh and Arumugasamy (2020) | |

|

|||

| E-commerce |

|

Pratheesh and Arumugasamy (2020) | |

|

|||

| GDP growth |

|

Bhalekar (2020) | |

|

|

|||

| Unemployment |

|

CMIE (2020b) | |

|

|

|||

| Employment |

|

CMIE (2020b) | |

|

|

SDG 11: Sustainable cities and communities

One of the indicators being air pollution has improved as indicated in Table 8.

Table 8.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 11

| SDGs 11—sustainable cities and communities | During COVID-19 lockdown | Post-COVID-19 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air pollution |

|

Gautam et al. (2020a) | |

|

SDG 13: Climate action

Due to industries' reduced footprint, the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions have decreased drastically, while biomedical waste has increased manyfold. The impacts are indicated in Table 9.

Table 9.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 13

SDG 14: Life below water

Aquatic life has suffered a loss due to increased dependency on fisheries for food during the lockdown, and the situation shall improve in the coming time. The impact is indicated in Table 10.

Table 10.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 14

| SDG 14—life below water | During COVID-19 lockdown | Post-COVID-19 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aquatic animals |

|

Pinder et al. (2020) | |

|

SDG 15: Life on land

Life on land has deteriorated due to reduced productivity in farms, mental and physical health problems. As the situation normalizes, the impacts may reduce as indicated in Table 11.

Table 11.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 15

| SDG 15—life on land | During COVID-19 lockdown | Post-COVID-19 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disruption of Indian farm |

|

CMIE (2020a) | |

|

SDG 17: Partnerships for the goals

The people's social security coverage has reduced, and hence the motion for SDGs has digressed its path, leading to negative impacts during the lockdown. The situation might improve in the long run. However, the partnership in the fight against COVID-19 would continue to improve indirectly, contributing to SDGs as shown in Table 12.

Table 12.

Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on SDG 17

| SDG 17—partnerships for the goals | During COVID-19 lockdown | Post-COVID-19 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social security coverage |

|

Impacts of Lockdown (2020) | |

|

Conclusion and future outlook

The study indicates that places with high air pollution levels before the lockdown scenario witness many COVID cases. The relation is evident for PM2.5, mostly responsible for respiratory disorders in the organ where SARS-CoV-2 sets. The relation is very clear in this case which provides usual evidence. For ozone, the relation is inverse in most of the states, while larger states like Madhya Pradesh cannot be commented upon. Moreover, the ranges of ozone are also restricted. Thus, it is difficult to obtain a clear relation as PM2.5 (Dutheil et al. 2020). More data on the state and cases may be helpful to get a clear picture of a starting point for future research.

The findings demonstrate the relation between COVID-19 and air quality using Thiessen polygons applied at a regional scale. Limited studies have reported the impact analysis using remote sensing and GIS. However, no single research is available to evaluate the confirmed cases and association with air quality by using rank algorithms for most or least suitable areas in Asian countries. Outcomes will be, however, useful as a pre-/post-processing tool for decision-makers.

Our study also indicates a larger agenda at hand when discussing SDGs for the impact they are suffering during this pandemic. The environmental factors such as air quality, water quality, and GHG emissions might have improved for a short duration; the impacts on GDP, poverty, health, and well-being have suffered a massive blow in India. These impacts may have repercussions for a long term and may hinder India’s steady growth in SDGs implementations which it had seen in past few years. The study paves the way for future holistic dialogues in this field as the lockdowns of countries will slowly start to lift, but the impacts shall be visible for long term.

In conclusion, a pandemic offers key challenges (i.e., social, health, environmental, and economic) for humans. Many studies (Jones et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2019) demonstrated the significant relationship between key challenges and viral agents. This presented work shows that air quality should be involved in an integrated approach to prevention of viral spreads, the protection of life, and environmental sustainable development (Chen et al. 2020; Bherwani et al. 2020b; Kaur et al. 2020). The approach did not entail or mortal component, morbidity, COVID-19 incidences, identification practices (i.e., population of area, total number of tests, total number of positive tests, etc.), lifestyle factors (i.e., smoking, diet, and drinking habits), and prevalence of preexisting conditions (i.e., respiratory issues, diabetes I and II types, cardiovascular diseases, etc.). Further, it is important to consider the local conditions, on ground, with respect to economic status, microclimatic conditions, social and health well-being, resource availability, and so on to quantify detailed impacts on SDGs in reference to COVID-19-related changes (Kaur et al. 2020; Bherwani et al. 2020c; Qiu et al. 2019). With these limitations, the outcomes of this study are merely hypothesis-generating. Future studies are required to highlight the present gap of knowledge and fix it toward the diffusion of the impact of COVID-19 in India.

Acknowledgement

HB and AK acknowledge Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), India, and its constituent laboratory National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) for providing the support for the research. The manuscript is checked for plagiarism using licensed iThenticate software wide KRC No.: CSIR-NEERI/KRC/2020/JUNE/CSUM-DRC-ERMD/1. SG would like to thank Karunya Institute of Technology and Sciences, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India, for providing us with the required funding and support during fieldwork and analysis.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Financial interests

The authors declare they have no financial interests.

References

- AajTak news (2020) Retrieved from May 31, 2020. https://aajtak.intoday.in/

- Bhalekar V. Novel corona virus pandemic-impact on Indian economy. E-Commer Educ Employ. 2020 doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3580342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj S, Singh S, Singh A, Singh HK, Singh HK et al (2020) Preprints, Basel, May 24. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202005.0403.v1

- Bhat BA, Gull S, Jeelani G, et al. A Study on COVID-19 lockdown impact on food, agriculture, fisheries and precautionary measures to avoid COVID-19 contamination. Galore Int J Appl Sci Human. 2020;4(2):8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H, Nair M, Musugu K, Gautam S, Gupta A, Kapley A, Kumar R. Valuation of air pollution externalities: comparative assessment of economic damage and emission reduction under COVID-19 lockdown. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2020;13:683–694. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00845-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H, Gupta A, Anjum S, Anshul A, Kumar R. Exploring dependence of COVID-19 on environmental factors and spread prediction in India. NPJ Clim Atmos Sci. 2020;3:38. doi: 10.1038/s41612-020-00142-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bherwani H, Singh A, Kumar R. Assessment methods of urban microclimate and its parameters: a critical review to take the research from lab to land. Urban Clim. 2020;34:100690. doi: 10.1016/j.uclim.2020.100690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, Luo F, Yu X, Zhang W, Li J, Zhao D, Xu D, Gong Q, Liao J, Yang H, Hou W, Zhang Y. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID-19 infection in nine pregnant women: a retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;20:30360–30363. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CMIE (2020a) Retrieved from June 23, 2020. https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-06-23%2017:28:28&msec=206

- CMIE (2020b) Retrieved from June 23, 2020. https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-06-16%2010:02:45&msec=733.

- Cohen AJ, Brauer M, et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis E, Telle O, Benkimoun S, Mukhopadhyay P, Nath S (2020) Mapping the lockdown effects in India: how geographers can contribute to tackle Covid-19 diffusion. Retrieved from June 23, 2020. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02551780/document

- Dutheil F, Baker JS, Navel V. COVID-19 as a factor influencing air pollution? Environ Pollut. 2020;263(Pt A):114466. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre For Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) (2020a) Retrived from June 23, 2020. https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=2020-05-12%2010:21:58&msec=653&ver=pf

- Emission rate (2020) Retrieved from June 23, 2020. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/26-decline-in-indias-carbon-emissions-due-to-covid-19-lockdown-study-2231872

- Fareed Z, Iqbal N, et al. Co-variance nexus between COVID-19 mortality, humidity, and air quality index in Wuhan, China: new insights from partial and multiple wavelet coherence. Air Qual Atmos Health Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00847-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S. The influence of COVID-19 on air quality in India: a boon or inutile. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2020;104:724–726. doi: 10.1007/s00128-020-02877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S. COVID-19: air pollution remains low as people stay at home. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00842-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S, Hens L. SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in India: what might we expect? Environ Dev Sustain. 2020;22:3867–3869. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00739-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S, Trivedi UK. Global implications of bio-aerosol in pandemic. Environ Dev Sustain. 2020;22:3861–3865. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00704-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam AK, Dilwaliya N, Srivastava A, Kumar S, Baudh K, Singh D, Gautam S. Temporary reduction in air pollution due to anthropogenic activity switch-of during COVID-19 lockdown in northern parts of India. Environ Dev Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00994-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam S, Brema J, Dasharathan R. Spatio-temporal estimates of solid waste disposal in an urban city of India: a remote sensing and GIS approach. Environ Technol Innov. 2020;18:100650. doi: 10.1016/j.eti.2020.100650. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humbal C, Gautam S, et al. Evaluating the colonization and distribution of fungal and bacterial bioaerosol in Rajkot, western India using multi-proxy approach. Air Qual Atmos Health. 2019;12(6):693–704. doi: 10.1007/s11869-019-00689-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Impacts of Lockdown (2020) Retrieved from 23 June, 2020. https://www.iddri.org/en/publications-and-events/blog-post/impacts-covid-19-india-risk-factors-sustainable-development-and

- Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature. 2008;451(7181):990–993. doi: 10.1038/nature06536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Bherwani H, Gulia S, Vijay R, Kumar R. Understanding COVID-19 transmission, health impacts and mitigation: timely social distancing is the key. Environ Dev Sustain. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00884-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochhar AS, Bhasin R, Kochhar GK, Dadlani H, Mehta VV, et al. Lockdown of 1.3 billion people in india during Covid-19 pandemic: a survey of its impact on mental health. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Tao ZW, Lei W, Ming-Li Y, Kui L, Ling Z, Shuang W, Yan D, Jing L, Liu HG, et al. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chin Med J. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad A, Kumar R et al (2020) Reduction in water pollution in Yamuna River due to lockdown under COV COVID-19 Pandemic. Chem Rxiv Preprint. https://doi.org/10.26434/chemrxiv.12440525.v1

- Nair M, Bherwani H, Kumar S, Gulia S, Goyal S, Kumar R. Assessment of contribution of agricultural residue burning on air quality of Delhi using remote sensing and modelling tools. Atmos Environ. 2020;230:117504. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2020.117504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paital B, Das K, Parida SK. Inter nation social lockdown versus medical care against COVID-19, a mild environmental insight with special reference to India. Sci Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinder AC, Raghavan R, Britton JR, Cooke SJ. COVID-19 and biodiversity: the paradox of cleaner rivers and elevated extinction risk to iconic fish species. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshw Ecosyst. 2020 doi: 10.1002/aqc.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poddar AK, Yadav BS. Impact of COVID-19 on Indian economy—a review. J Human Soc Sci Res. 2020;2(1):15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pratheesh JT, Arumugasamy G, et al. Impact of corona virus in Indian economy and banking sector—an overview. Stud Indian Place Names UGC Care J. 2020;40(18):2090–2101. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Chen X, Shi W. Impacts of social and economic factors on the transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China. J Popul Econ. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00778-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan MR, Tripathi A, Sharma G. Medical waste generation during COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic and its management: an Indian perspective. Asian J Environ Ecol. 2020;13(1):10–15. doi: 10.9734/ajee/2020/v13i130171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Zhang M, Anshika GJ, Zhang H, Kota SH. Effect of restricted emissions during COVID-19 on air quality in India. Sci Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobías A, Carnerero C, Reche C, Massagué J, et al. Changes in air quality during the lockdown in Barcelona (Spain) one month into the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic. Sci Total Environ. 2020;726:138540. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. The Lancet. 2020;395(10223):470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-2019) situation reports.World Health Organization, Geneva. Retrieved from March 23, 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/opensinnewtab

- Yunus AP, Masago Y, Hijioka Y. COVID-19 and surface water quality: Improved lake water quality during the lockdown. Sci Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]